Abstract

Background

Verapamil (VER) and cilostazol (Cilo) are mostly used as cardiovascular drugs; they have beneficial effects on different organs toxicities.

Aim

we investigated whether the Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2), Glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK-3β), and Nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) pathway involved in the protective role of these drugs against Thioacetamide (TAA) induced hepatotoxicity.

Method

male rats were randomized divided into five groups, each group (n = 10): control, TAA, VER+TAA, Cilo+TAA, and VER+Cilo+TAA groups. Hepatotoxicity induced in rats by TAA injection once on the 7th day of the experiment.

Results

TAA-induced hepatotoxicity indicated by a significant elevated in serum markers (Alanine aminotransferases (ALT), Aspartate aminotransferases (AST), and bilirubin), oxidative stress markers (Malondialdehyde (MDA), and Nitric oxide (NO)), and protein levels markers (NF-κB, and S100 calcium-binding protein A4 (S100A4)). Also, TAA decreased Nrf2, and increased GSK-3β genes expression. Histopathological alterations in the liver also appeared as a response to TAA injection. On the other hand VER and/or Cilo significantly prevented TAA-induced hepatotoxicity in rats through significantly decreased in ALT, AST, bilirubin, MDA, NO, NF-κB, and S100A4 protein levels. Also, they increased Nrf2 and decreased GSK-3β genes expression which caused improvement in the histopathological changes of the liver.

Conclusion

the addition of verapamil to cilostazol potentiated the hepatoprotective activity, and inhibited the progression of hepatotoxicity caused by TAA through the Nrf2/GSK-3β/NF-κBpathway and their activity on oxidative stress, inflammation, and NF-κB protein expression.

Keywords: hepatotoxicity, cilostazol, thioacetamide, verapamil, Nrf2, GSK-3β

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

Highlights

Verapamil and cilostazol protected against TAA-induced hepatotoxicity in rat.

Verapamil and cilostazol reduced NFĸB and S100A4 protein.

Nrf2/GSK-3β/NFĸB defensive pathways exerted protection against TAA-induced hepatotoxicity.

Verapamil and cilostazol altered expression of Nrf2 (up), and GSK-3β receptors (down).

Introduction

Hepatotoxicity refers to liver damage caused by a variety of factors including chemicals and xenobiotics, which have effects on hepatic cell structure, functions, and lead to death.1 Thioacetamide (TAA) is a dangerous type of xenobiotic (organ sulfur compound) that leads to hepatic malfunction and toxicity. TAA is an organic fungicidal compound that exerts toxics on liver cells due to its hepatic metabolites, and release of inflammatory mediators.2,3 Reactive metabolites of TAA lead to oxidative damage, hepatic necrosis, and toxicity.4,5 TAA-induced liver damage by damaging the endothelial barrier, which induces apoptosis of hepatocytes and inflammatory cytokines that activate macrophages and hepatic stellate cells.6

S100 calcium-binding protein A4 (S100A4) acts as an activating factor of hepatic stellate cells.7 S100A4 enhances chemical stimulation, recruitment of inflammatory cells (neutrophils, leukocytes, and macrophages), and enhances the movement of these inflammatory cells to regulate immune and inflammatory functions.8

Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) offers a cellular defense against oxidative stress by inducing the expression of antioxidant and detoxification enzymes that fight against oxidative stress caused by TAA exposure.9,10 Many factors regulate Nrf2 such as Glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK-3β), which plays a vital role in controlling the Nrf2 activity.11 GSK-3β is a serine/threonine kinases that can contribute in pro-apoptotic signaling.12 Hepato-protection can be reached by accelerating Nrf2 antioxidant response and this can be achieved by the inhibition of GSK3β phosphorylation.13

Cilostazol (Cilo) is a selective type-3 phosphodiesterase (PDE-3) inhibitor, which is used for the treatment of thrombotic diseases due to its antiplatelet properties.14 The main side effect of Cilo is the risk of congestive heart disease, as it may increase heart rate and can cause tachycardia and arrhythmia.15 Long-term effects of PDE-3 inhibitor administration in congestive heart failure patients, reported increased cardiovascular mortality.16 So Cilo is contraindicated in the patient with a history of heart failure. Cilo inhibits inflammation and oxidative stress by upregulation of the Nrf2 signaling pathway.17,18

Verapamil (VER) is a calcium channel blocker that is used in the treatment of hypertension.19 VER has antioxidant properties, and acts as a strong Nrf2 activator.20 This may help in ameliorating liver injury through upregulation of the Nrf2 pathway.21

The current study was conducted to examine the regulatory effect of both drugs (VER and Cilo) on GSK3β and Nrf2 antioxidant response in hepatic cells, and to compare the hepatoprotective effects of the combination of both drugs with each drug alone.

Materials and methods

Animals

Male Wistar rats (210–220 g) were purchased from the unit of experimental animal production at Vacsera, Giza, Egypt. Rats were maintained under controlled temperature (23 ± 2οC), and relative humidity (60 ± 10%) conditions, with a 12/12-h light/dark cycle. They were kept 1 week in the laboratory before the experiment for acclimatization. All experimental procedures described in this study comply with the ethical principles and guidelines for the use and care of experimental animals established in the “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, 8th ed,”22 and accepted in Faculty of Pharmacy, Tanta University.

Drugs, chemicals, and kits

Cilo powder was obtained as a gift from (Pharmacare Company, Egypt). VER powder was obtained as a gift from (El-Qahera For Pharmaceutical & Chemical Industries). TAA powder was purchased from (Lobe Chemie, India). Dimethyl sulphoxide (DMSO, 0.1%) was purchased from (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, United States). Cilo was dissolved in (DMSO, 0.1%),23VER was dissolved in water, and TAA was dissolved in normal saline. A quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) kit and the primers for (GSK-3β and Nrf2) were purchased from (Thermo Fisher Scientific, United States and Glory Science Co., Ltd). ELISA kits for (S100 A4) were purchased from (Sun Red Biological Technology Co., Ltd, China). ALT, AST, and total bilirubin kits were obtained from the (Biodiagnostic Company, Egypt). Antibodies used for the western blot analysis for (GSK-3β and Nrf2), were purchased from (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., Europe). Other chemicals were used in analytical grade, and acquired commercially.

Experimental protocol

Rats were randomly assigned into 5 groups (n = 10) as follows:

Control group: Rats received vehicle (saline and DMSO) daily.

TAA group: Hepatotoxicity was induced by a single dose of TAA (150 mg/kg, i.p.) on the 7th day of the experiment.24

Cilo+TAA group: Rats received Cilo (10 mg/kg/day; p.o.) followed by a single dose of TAA (150 mg/kg; i.p.) 3 h after the last dose of treatment.21

VER+TAA group: Rats received VER (5 mg/kg/day; p.o.) followed by a single dose of TAA (150 mg/kg; i.p.) 3 h after the last dose of treatment.21

Cilo+VER+TAA group: Rats received Cilo (10 mg/kg/day; p.o.) and VER (5 mg/kg/day; p.o.) followed by a single dose of TAA (150 mg/kg; i.p.) 3 h after the last dose of treatment.

All drugs were administered daily for a total of 7 days.

Sample collection

On the 8th day of the experiment, rats were drugged by 1.5-g/kg urethane after 12 h of fasting (urethane used for anesthesia). After decapitation, blood samples were collected and centrifuged at 4,000 rpm for 20 min for serum collection. Clear serum was kept at −20°C for assessment of biochemical parameters (ALT, AST, and bilirubin). The liver of each rat was dissected and divided into 3 parts: The first part of the liver was homogenized in phosphate buffer (pH 7.4), and then centrifuged to obtain supernatant for assessment of different biological parameters; the second part was used for RNA extraction; and the third part was kept in 10% formalin for histopathological examination.

Biochemical analysis

Serum parameters

Serum obtained was used for assessment of ALT, AST, and bilirubin using commercial kits (Biodiagnostic Company, Cairo, Egypt), and according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Hepatic homogenate parameters

Portions of the liver were homogenized in phosphate buffer (pH 7.4), and then centrifuged to obtain supernatant for assessment.

Assessment of malondialdehyde content (μmol/g tissue)

The lipid peroxidation product, malondialdehyde (MDA), was measured spectro-photometrically (T80+ PG Instruments) at 535-nm wavelength after its reaction with thiobarbituric acid, as described by Yoshioka et al.25

Assessment of reduced glutathione GSH content (μmol/gtissue)

Hepatic tissue concentration of the antioxidant, glutathione (GSH) was determined according to the methods of ref.26 The method is based on the reduction of Ellman’s reagent [5,5′-dithio-bs-(2-nitrobenzoic acid)], yellow color formed can be determined spectro-photometrically (T80+ PG Instruments) at 412 nm.

Assessment of total nitric oxide concentrations in hepatic tissue content (μmol/g tissue)

Nitric oxide (NO) production, was measured as the stable end-product nitrite according to the method of ref.27 This assay is based on the reduction of Griess reagent. The colored product was measured spectro-photometrically (T80+ PG Instruments) at 540 nm.

Estimation of S100A4 in hepatic tissues

Quantitative levels of S100 A4 in hepatic tissues were measured according to purchased ELISA kit instructions (Sunred Biological Technology Co., Ltd, China). The optical density was measured spectro-photometrically by using a microplate reader (Tecan infinite 50) set to 450 nm.

Real-time quantitative PCR

Hepatic tissue was analyzed for the relative gene expressions of Nrf2 and GSK 3β using real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR). The extraction of RNA from hepatic tissue was performed by TRiazol RNA extraction reagent (AMRESCO, Solon, United States). Purification of RNA using RNeasy kit (QIAGEN, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. cDNA was synthesized by reverse transcription using (Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). One-step kit with 50-ng RNA template per reaction in 25-mL reaction volume. Primers used sequence were purchased from (Thermo Fisher Scientific, United States and Glory Science Co., Ltd). Analysis of the SYBR Green data (Thermo Fisher Scientific; Fremont, CA, United States) was performed and quantified to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) as a reference gene. The sequences of the used primers were: Nrf2 gene: sense 5′-TAC TCC CAG GTT GCC CAC A-3′, antisense 5′-CAT CTA CAA ACG GGA ATG TCT GC-3′; GSK 3β gene: sense 5′- GGA ACT CCA ACA AGG GAG CA-3′, antisense 5′-TTC GGG GTC GGA AGA CCT TA-3′; and GAPDH gene: sense 5′-GTCGGTGTGAACGGATTTG-3′, antisense 5′- CTTGCCGTGGGTAGAGTCAT-3′.28,29 The conditions of RT-qPCR reaction were as follows: 95°C initial denaturations for 15 min, 40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 10 s, annealing at 60°C for 15 s, and elongation at 72°C for 1 min, and final elongation at 72°C for 10 min. The expression level of genes was calculated and mounted relative to control, where control samples were set at a value of 1.30 The PCR products were analyzed by electrophoresis and the results were analyzed by Opticon Monitor 3 software.

Western blot analysis

The Ready Prep TM protein extraction kit (total protein) provided by Bio-Rad Inc. (Catalog #163-2086) was employed according to manufacturer instructions was added to each sample of the homogenized liver tissues of all different groups. Bradford Protein Assay Kit (SK3041) for quantitative protein analysis was provided by Bio Basic Inc. (Markham Ontario L3R 8T4 Canada). A Bradford assay was performed according to manufacture instructions to determine protein concentration in each sample. Twenty-microgram protein concentration of each sample was then loaded with an equal volume of 2x Laemmli sample buffer containing 4% SDS, 10% 2-mercaptoethanol, 20% glycerol, 0.004% bromophenol blue, and 0.125-M Tris HCl. The pH was checked and brought to 6.8. Each previous mixture was boiled at 95°C for 5 min to ensure denaturation of protein before loading on polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Polyacrylamide gels were performed using TGX Stain-Free FastCast Acrylamide Kit (SDS-PAGE), which was provided by Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc. Cat # 161-0181. The SDS-PAGE TGX Stain-Free FastCast was prepared according to manufacture instructions. The gel was assembled in a transfer sandwich as follows from below to above (filter paper, PVDF membrane, gel, and filter paper). The sandwich was placed in the transfer tank with 1× transfer buffer, which is composed of 25-mM Tris, 190-mM glycine, and 20% methanol. Then, the blot was run for 7 min at 25 V to allow protein bands to transfer from gel to membrane using BioRad Trans-Blot Turbo. The membrane was blocked in tris-buffered saline with Tween 20 (TBST) buffer and 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA) at room temperature for 1 h. The components of the blocking buffer were as follows: 20-mM Tris pH 7.5, 150-mM NaCl, 0.1% Tween 20, and 3% BSA. Primary antibodies of Nrf2 and GSK3β were purchased. The primary antibody was diluted in TBST (1:500) according to manufactured instructions. Incubation was done overnight in each primary antibody solution, against the blotted target protein, at 4°C. The blot was rinsed 3–5 times for 5 min with TBST. Incubation was done in the HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (Goat anti-rabbit IgG- HRP-1 mg Goat mab -Novus Biologicals) solution against the blotted target protein for 1 h at room temperature. The blot was rinsed 3–5 times for 5 min with TBST. The chemiluminescent substrate (Clarity TM Western ECL substrate Bio-Rad cat#170-5060) was applied to the blot according to the manufacturer’s recommendation. Briefly, equal volumes were added from solution A (Clarity western luminal/enhancer solution) and solution B (peroxidase solution). The chemiluminescent signals were captured using a CCD camera-based imager. Image analysis software was used to read the band intensity of the target proteins against the control sample beta-actin (housekeeping protein) by protein normalization on the ChemiDoc MP imager.

Histopathological examination of hepatic tissue

Hepatic tissue was removed from formalin, and embedded in paraffin to prepare 5-μm sections for staining with hematoxylin–eosin (H&E). Slides were examined under a light microscope (Olympus BX 51). The severity of the liver injury was scored according to modified HAI grading necro-inflammatory score, which is based on four findings: (i) periportal hepatitis, (ii) confluent necrosis, (iii) focal (spotty) lytic necrosis, apoptosis, and focal inflammation, and (iv) portal inflammation. The final score was calculated by the summation of the four categories of necro-inflammation per rat.31

Immunohistochemical expression of Nuclear factor-kappa (NF-ĸB-P65) protein in hepatic tissues

The immunohistochemical staining procedures were done as described.32 Briefly, sections were dewaxed and immersed in a solution of 0.05-M citrate buffer, pH 6.8 for antigen retrieval. These sections were then treated with 0.3% H2O2 and protein block. Then, sections were incubated with polyclonal anti-NF-ĸB P65, Santa Cruz, Cat# (F-6): sc-8008, 1:100 dilution PCNA. After rinsing with phosphate-buffered saline, they were incubated with a goat anti-rabbit (Cat# K4003, EnVision+ System Horseradish Peroxidase Labelled Polymer; Dako) for 30 min at room temperature. Slides were visualized with a DAB kit, and eventually stained with Mayer’s hematoxylin as a counterstain. The staining intensity was assessed and presented as a percentage of positive expression in a total of 1,000 cells per 8 HPF.32

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as mean ± SD. Results were analyzed using a 1-way analysis of variance test (1-way ANOVA) followed by Tukey–Kramer multiple comparison test. Statistical analysis was carried out using Graph Pad Prism software version 8; a probability level of (P < 0.05) was accepted as statistically significant.

Results

Effects of drug treatment on hepatic functions

Serum ALT, AST, and bilirubin were used traditionally as indicators of liver injury. As presented in Table 1. Rats injected by TAA displayed a significant rise in their levels as compared with control rats. TAA-induced hepatic damage resulted in a significant elevation of ALT (7.99-fold) and AST (6.21-fold) levels compared with control rats. Similarly, total bilirubin increased by 4.28-fold as compared with control. On the other hand, VER and/or Cilo-treated groups significantly decreased ALT, AST, and bilirubin levels compared with the TAA group. VER and Cilo combination significantly decreased the level of hepatic enzyme more than each drug alone.

Table 1.

Effect of Cilo, VER, and their combination on serum hepatic ALT, AST, and bilirubin.

| Groups | ALT (U/l) | AST (U/l) | Bilirubin (mg/dl) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 22.8 ± 3.6 | 24.6 ± 3.9 | 2.8 ± 0.78 |

| TAA | 205 ± 12.5* | 177.4 ± 7.1* | 14.8 ± 1.1* |

| Cilo+TAA | 118.8 ± 4.1*,# | 125.4 ± 5.5*,# | 9.63 ± 0.49*,# |

| VER+TAA | 121. 4 ± 9.8*,# | 115.6±6.7*,# | 9.85 ± 0.54*,# |

| Cilo+VER + TAA | 72.8 ± 6.7*,#,a,b | 73.2 ± 6.3*,#,a,b | 6.48 ± 0.43*,#,a,b |

Values are represented as mean ± SD.

#Significant difference from TAA group at P < 0.05.

aSignificant difference from the Cilo+TAA group at P < 0.05.

bSignificant difference from VER + TAA group at P < 0.05.

*Significant difference from the control group at P < 0.05.

Effects of drug treatment on hepatic oxidative stress markers

GSH activity exerts a protective activity against oxidative stress. It helps combat free radicals that can damage cell structure and function, whereas MDA concentration has been usually used as an indication of lipid peroxidation, indicating the oxidative injury of the cell plasma membrane. As shown in Table 2, TAA displayed a significant harmful effect on hepatic antioxidant defenses with a significant elevation in the lipid peroxidation product MDA in hepatic tissue. TAA-induced hepatotoxicity significantly increased MDA level with a reduction in GSH activities in hepatic tissues as compared with the control group. On the other hand, Cilo and/or VER significantly reduced MDA levels to their normal values and restored the antioxidant status of the liver as they increased GSH content compared with TAA hepatotoxic group. The hepatic tissue content of NO is significantly increased in the TAA group as compared with control rats. The hepatic NO content was reduced after Cilo and/or VER treatment as compared with the hepatotoxic group. Also, VER and Cilo combination more significantly improved the deleterious effect of TAA on hepatic antioxidant defense compared with each drug alone.

Table 2.

Effect of Cilo, VER, and their combination on hepatic oxidative stress.

| Groups | MDA(μmol/g) | NO(μmol/g tissue ) | GSH (μmg/g tissue ) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 39.6±4.3 | 99.6±5.3 | 1,286 ± 2.7 |

| TAA | 120.6±3.3* | 513.7±7.1* | 613.9 ± 4.9* |

| Cilo+TAA | 99.6±6.2*,# | 214.2±6.8*,# | 1,116 ± 4.2*,# |

| VER+TAA | 98.4 ± 4.1*,# | 215.3±8.5*,# | 1,131±5.5*,# |

| Cilo+VER + TAA | 76.2 ± 5.3*,#,a,b | 184.7±5.4*,#,a,b | 1,181 ± 2.1*,#,a,b |

Values are represented as mean ± SD.

#Significant difference from TAA group at P < 0.05.

*Significant difference from the control group at P < 0.05.

aSignificant difference from the Cilo+TAA group at P < 0.05.

bSignificant difference from VER+TAA group at P < 0.05.

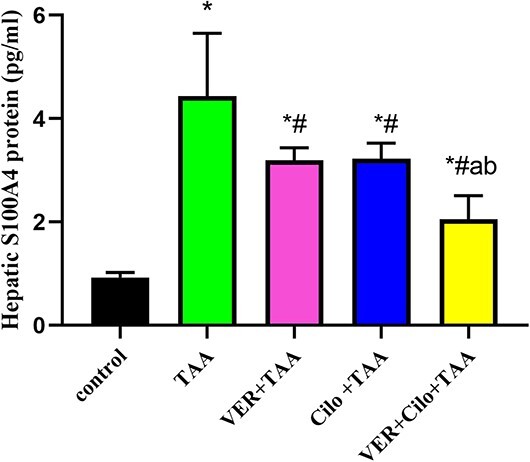

Effect of drug treatment on hepatic S100 A4 protein level

As presented in Fig. 1, TAA-induced hepatic injury is associated with a significant increase in S100A4 protein level as compared with the control group. These levels were markedly decreased in Cilo and/or VER-treated groups as compared with the TAA group. However, combined drugs decreased their levels significantly more than VER and Cilo-treated groups.

Fig. 1.

The effect of drugs on hepatic S100 A4 protein level.

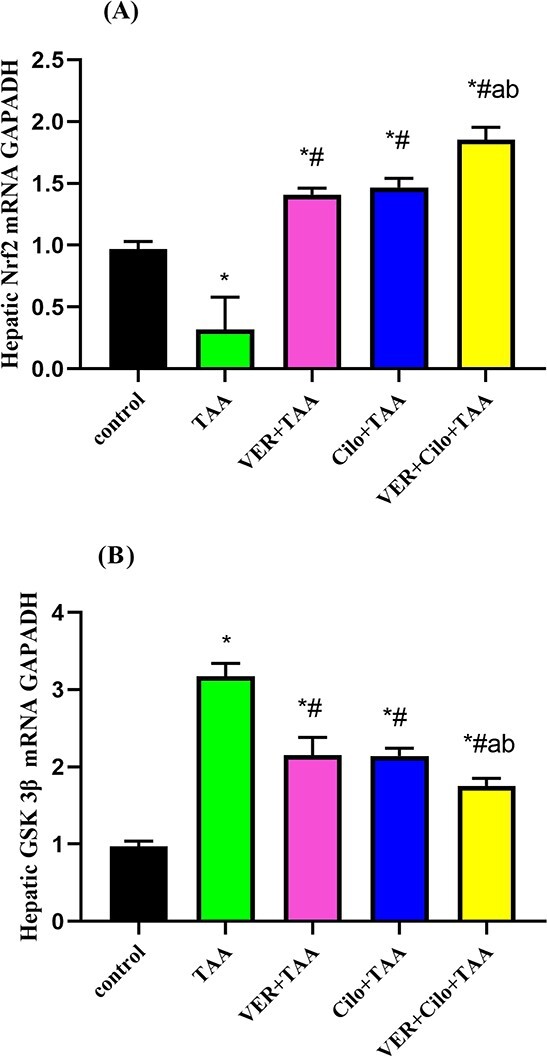

Effect of drug treatment on hepatic Nrf2 and GSK-3β mRNA expression

As presented in Fig. 2 (A and B), the relative expression of Nrf2 (A) and GSK-3β (B) mRNAs in hepatic tissue demonstrated that TAA caused liver toxicity revealed by a significant reduction in Nrf2 (65%), and a significant rise in GSK 3β mRNAs expression (3.17-fold) in comparison with the control group. Cilo and/or VER-treated groups resulted in a significant upregulation of Nrf2 (1.47, 1.41, and 1.85-folds, respectively), and a significant downregulation of GSK3β (32.49%, 32.1%, and 44.79%, respectively) mRNAs expression as compared with the TAA group. Also, the combination group (VER+Cilo+TAA) showed a more significant increase in Nrf2 mRNA expression, and a more significant decrease in GSK-3β mRNA expression compared with each treated drug alone.

Fig. 2.

A and B) The effect of drugs on hepatic Nrf2 (A), and GSK 3β (B) mRNA expression.

Effect of drug treatment on hepatic Nrf2 and GSK-3β protein expression

As presented in Fig. 3 (A and B), the relative protein expression of Nrf2 and GSK-3β in hepatic tissue demonstrated that TAA caused liver toxicity revealed by a significant reduction in Nrf2 (86.6%), and a significant increase of GSK-3β in protein expression (2.12-fold) in comparison with the control group. Cilo and/or VER-treated groups resulted in a significant increase in Nrf2 (by 70%, 78.6%, and 84.41%, respectively), and a significant reduction in GSK-3β protein expression (by 34.72%, 43.71%, and 63.8%), as compared with the TAA group. Also, the combination group (VER+Cilo+TAA) showed a more significant increase in Nrf2 protein expression, and a more significant reduction in GSK-3β protein expression compared with each treated drug alone.

Fig. 3.

(A and B) The effect of drugs on hepatic Nrf2, and GSK-3β protein expression.

Histopathological examination of hepatic tissue

Histopathology examination of the control group showed normal liver tissue [H&E 200x; Fig. 4a)]. TAA administration in rats caused hemorrhage, inflammatory cellular infiltration, and disorganized hepatocytes causing a severe liver injury (Fig. 4b). TAA showed loss of the liver architecture with surrounding inflammation around periportal tracts tissue, and mixed inflammatory infiltrate with piecemeal necrosis and extensive hydropic degeneration of the liver cells tissue. TAA hepatotoxic group showed a severe distortion of architecture, periportal lymphocytic infiltration, areas of hemorrhage, and necrosis (Fig. 4b). TAA show portal inflammation severs around >50% of septa [4] with focal spotty necrosis in four foci per 10 objectives [2], and moderate to marked portal inflammation in all portal tract [3] grade 9/18 according to modified HAL grading.31

Fig. 4.

A) (a–e) A photomicrograph of hepatic tissue (H&E 200x), the scale bar =50 μm. Control (a), TAA (b), VER+TAA (c), Cilo+TAA (d), and VER+Cilo+TAA (e). B) Hepatic necro-inflammation score.

On the other hand, These pathological changes were significantly disappeared in rats treated by VER (Fig. 4c), and/or by Cilo (Fig. 4d) where VER and/or Cilo showed restoration of hepatic architecture with less parenchymal injury. Also, the combination group showed mild periportal inflammation [1], no necrosis [0], mild portal tract inflammation [1], and grade 2/18 (Fig. 4e). The combination group showed more liver protection from TAA administration in rats than in each group alone where (VER+TAA) showed severe continuous interphase hepatitis on >50% [4], with focal confluent necrosis [1], marked portal inflammation [4], grade 9/18 (Fig. 4c), and (Cilo+TAA) showed interphase hepatitis moderate in most areas [2], and mild portal inflammation in some portal tract [1], grade 3/18 (Fig. 4d). The severity of the liver injury was scored according to modified HAI grading necro-inflammatory score, which was based on four findings; periportal hepatitis, confluent necrosis, apoptosis, and portal inflammation. The final score was calculated by the summation of the four categories of necro-inflammation per rat (Fig. 4B).31

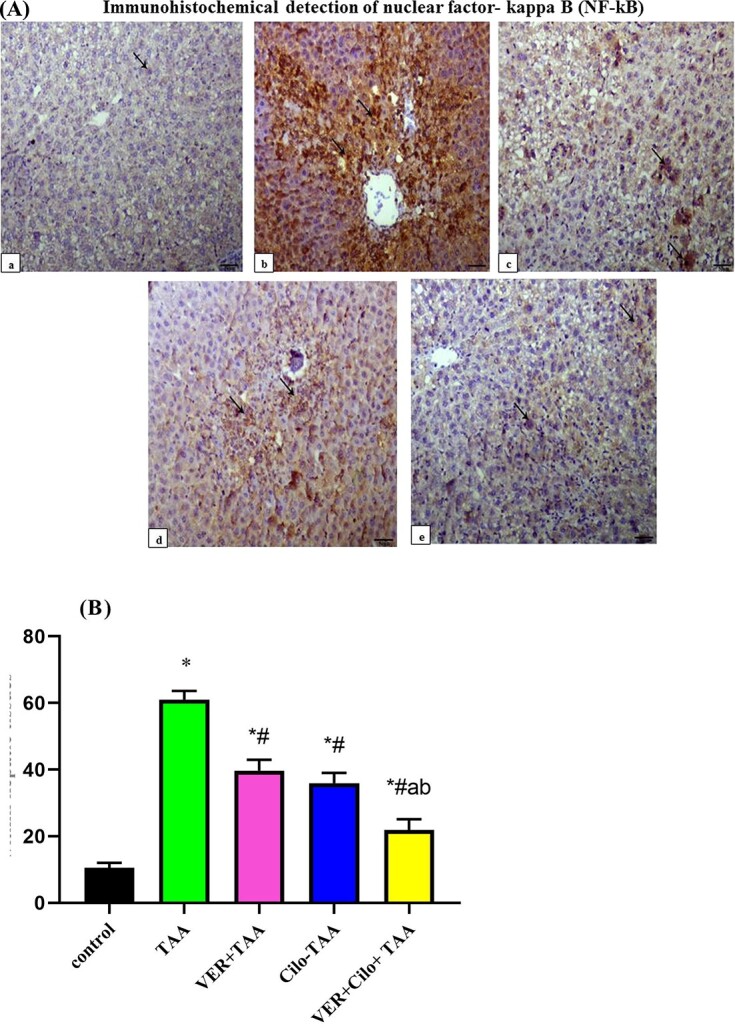

Immunohistochemical expression of NFĸB-P65 in hepatic tissues

The nuclear and/or cytoplasmic immune staining intensity for NF-kB subunit scored according to.32 As shown in Fig. 5A (a–e); the control (a) group showed normal hepatic tissue with no or fewer nuclear positive cells stained within hepatic tissue. TAA toxic group showed more Centro-lobular immunostaining of NFĸB-P65 within hepatocytes with >70% of nuclear positive cells stained within hepatic tissue (b) compared with the control group. On the other hand, VER or Cilo-treated groups (c and d) showed 30–40% nuclear positive cells stained within hepatic tissue, and moderately decrease NFĸB-P65 expression within hepatocytes compared with the TAA group. Combination treated group showed 10–20% nuclear positive cells stained within hepatic tissue and a marked decrease in NFĸB-P65 expression within hepatocytes (e). Percent of nuclear positive cells within hepatic tissues are shown in (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

A) (a–e) Immunohistochemical detection of nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-kB), IHC NFĸB-P65, 200x, the scale bar = 50 μm. Control (a), TAA (b), VER+TAA (c), Cilo+TAA (d), and VER+Cilo+TAA (e). B) Percent of nuclear positive cells within hepatic tissues.

Discussion

The current study presents a new insight into molecular mechanisms for Cilo and VER hepatoprotective effects in a model of hepatotoxicity. TAA has been considered one of the most industrial xenobiotics, which exert harmful effects on different cells specifically, hepatocytes and renal tubular cells.21,33

In our research, the TAA-induced hepatotoxicity model is well-established by histopathological examination as the TAA group showed epithelial cells injury of hepatic tissue, hepatocellular necrosis with infiltration of inflammatory cells and apoptosis. TAA induces hepatotoxicity through elevation of hepatic injury markers ALT, AST, and bilirubin together with the disruption of hepatic lobules that indicated damaged hepatic cells.14,28 TAA induces hepatic oxidative damage manifested by lipid peroxidation, and deterioration of antioxidant defense mechanisms in the liver. TAA causes a significant elevation in MDA, NO, and a decrease in GSH levels in hepatic tissue.34,35 Furthermore, TAA causes a significant increase in S100A4 protein and NF-ĸB, which results in hepatic fibrosis, inflammation, necrosis, and toxicity. This is in line with previous reports.36,37

In the present study, we found that VER and/or Cilo significantly ameliorated the oxidative reactions generated by TAA, as observed by the marked reduction in hepatic function, hepatic oxidative, and nitrosative stress markers. This was associated with a significant decrease in ALT, AST, bilirubin, MDA, NO, and with an elevation of GSH hepatic tissue. This is in line with previous reports.14,20,21 In addition, S100 A4 protein, and NF-ĸB were significantly decreased. The present study showed that TAA significantly downregulated the expression levels of Nrf2 and upregulated the expression levels of GSK-3β causing hepatic inflammation, necrosis, and toxicity.

Recent studies demonstrated that there is a relation between GSK-3β and Nrf2, leading to the belief that both are major factors in the protection against TAA-induced hepatotoxicity.11,12 On the other hand, we found that VER and/or Cilo significantly upregulated the mRNAs and protein expression levels of Nrf2, and significantly downregulated the mRNAs and protein expression levels of GSK3β, and that may be responsible for hepatoprotective activity against TAA-induced hepatotoxicity.

Nrf2 is responsible for the anti-inflammatory process by the recruitment of inflammatory cells and regulating gene expression through the antioxidant response element (ARE), which regulates anti-inflammatory gene expression, and inhibits the progression of inflammation. The NF-κB signaling pathways are involved in the development of the classical pathway of inflammation. Nrf2 acts as an indirect inhibitor of the NF-ĸB pathway, which leads to a decrease in expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines, and decreases hepatic inflammation.38 Upregulation of Nrf2 signaling inhibits the overproduction of pro-inflammatory cytokines, and chemokines as well as limiting the activation of NF-κB, which regulate the inflammation and cell death.39 So activation of Nrf2 can cause the inhibition the nuclear translocation of NF-κB, and inhibit the inflammatory response.40

On the other hand, GSK-3β regulates the activity of NF-κB, where it can phosphorylate NF-κB.29,41 So, GSK-3β inhibition or downregulation leads to a decrease in NF-κB activity.42,43 GSK-3β can affect on NF-κB activity through inhibition of the NF-κB complex from binding to certain target promoters through histone methylation lead to initiation to the inflammation.44,45 GSK-3β is a crucial protein involved in Nrf2 stabilization and regulation; it phosphorylates Nrf2 in the Neh6 domain (which plays an important role in Nrf2 regulation) leading to degradation of the Nrf2 transcription factor, and protein degradation. So Nrf2 was stabilized by GSK-3 inhibitors. Nrf2 is destabilized as a consequence of its phosphorylation by GSK-3β.46,47

So when we prevent Nrf2 phosphorylation by GSK3-3β, it prevents protein degradation, inflammation, and tissue damage leading to protection. VER and/or Cilo significantly downregulate the expression level of mRNA of GSK-3β, and that may protect Nrf2 from phosphorylation, and prevent its degradation by GSK-3β leading to possible hepatic protection from protein degradation. At the same time the drugs also significantly upregulate the expression level of mRNA of Nrf2 causing more hepatic protection. We notice that the combined drugs show significantly more upregulation of mRNA of Nrf2, and more downregulation of the mRNA expression level leads to possible more hepatic protection. Also inhibition of GSK-3β lead to reduce the inflammation and hepatotoxicity, and this is in line with previous reports.48

Our results demonstrate that VER and/or Cilo protect the liver from TAA-induced toxicity by activating Nrf2, and induction of inhibition of phosphorylation of GSK3β. So we can say that the drugs act as GSK-3β inhibitors and may protect the liver from the toxicity through Nrf2/GSK-3β pathway.

S100A4 activates NF-κB by inducing its phosphorylation to activation of the pro-inflammatory transcription factor, and increase NF-κBactivity.49,50 Several studies have demonstrated increased activation of NF-κB upon stimulation with S100A4 in a variety of cell systems.51–53 The drugs significantly decrease S100A protein level, and NF-κB protein expression in hepatic tissue lead to a decrease in the hepatic tissue inflammation caused by TAA.

The present data suggest that this defense mechanism against TAA-induced hepatotoxicity involves Nrf2/GSK-3β/NF-κB pathway. Cilo exerts a preventive role on oxidative insults through targeting Nrf2 and GSK-3β pathway induction, and restoring the redox defense mechanisms, and this is in line with previous reports.21,54,55

Also,VER acts as an effective (Nrf2) activator and (GSK-3β and NF-κB) inhibitor. VER induced Nrf2 activation was complemented by upregulation of the Nrf2 target gene. In agreement with our findings, VER was previously found to exert a protective effect in different cardiac and hepatic models by antioxidant and anti-inflammatory potential.21,28

Based on results and the previous knowledge, we have suggested that the combined drug effects on Nrf2/GSK-3β/NF-κB levels are much higher than the effect of each drug alone. These findings may be related to synergistic antioxidant and anti-inflammatory roles.

Conclusion

Cilo and VER exerted protection against TAA-induced acute hepatic damage through targeting Nrf2/GSK-3β/NF-κB defensive pathway. A combination of both afforded a synergistic effect, as they share the same mechanism. The combination of both drugs could be a better therapeutic option in the liver diseases associated with cardiac problems.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr WaliedAbdo (associate professor of Pathology, Faculty of Veterinary medicine, Kafr el sheik University) for his precious help in immunochemical of NF-κB and Dr Darin Abdel Azeez (associate professor of Pathology, Faculty of Medicine, Tanta University) for her help on histopathological examination.

Contributor Information

Alaa E Elsisi, Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology, Faculty of Pharmacy, Tanta University, Tanta, Egypt.

Esraa H Elmarhoumy, Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology, Faculty of Pharmacy, Tanta University, Tanta, Egypt.

Enass Y Osman, Department of Pharmacology and Toxicology, Faculty of Pharmacy, Tanta University, Tanta, Egypt.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest concerning the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Authors’ contributions

All listed authors meet authorship requirements. Esraa H. Elmarhoumy did formal analysis, data curation, project administration, participated in the research design, analyzed the data, and performed the in-vivo drug administration. Enass Y. Osman did formal analysis, data curation, project administration, and analyzed the data. Alaa E. Elsisi was involved in formal analysis, data curation, project administration, designing the research, and took the responsibility of writing—original draft. Alaa E. Elsisi and Enass Y. Osman were involved in project supervision.

References

- 1. Gu X, Manautou JE. Molecular mechanisms underlying chemical liver injury. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2012:14:e4. doi: 10.1017/S1462399411002110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wahsh E, Abu-Elsaad N, El-Karef A, Ibrahim T. The vitamin D receptor agonist, calcipotriol, modulates fibrogenic pathways mitigating liver fibrosis in-vivo: an experimental study. Eur J Pharmacol. 2016:789:362–369. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2016.07.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Miguel FM, Schemitt EG, Colares JR, Hartmann RM, Morgan-Martins MI, Marroni NP. Action of vitamin e on experimental severe acute liver failure. ArqGastroenterol. 2017:54(2):123–129. doi: 10.1590/S0004-2803.201700000-03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Delire B, Stärkel P, Leclercq I. Animal models for fibrotic liver diseases: what we have, what we need, and what is under development. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2015:3(1):53–66. doi: 10.14218/JCTH.2014.00035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Al-Attar AM, Alrobaiand AA, Almalki DA. Protective effect of olive and juniper leaves extracts on nephrotoxicity induced by thioacetamide in male mice. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2017:24(1):15–22. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2015.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kisselevaand T, Brenner DA. Fibrogenesis of parenchymal organs. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2008:5(3):338–342. doi: 10.1513/pats.200711-168DR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chen L, Li J, Zhang J, Dai C, Liu X, Wang J, Gao Z, Guo H, Wang R, Lu S, et al. S100A4 promotes liver fibrosis via activation of hepatic stellate cells. J Hepatol. 2015:62(1):156–164. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fei F, Qu J, Li C, Wang X, Li Y, Zhang S. Role of metastasis-induced protein S100A4 in human non-tumor pathophysiologies. Cell Biosci. 2017:7:64. doi: 10.1186/s13578-017-0191-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Taguchi K, Motohashiand H, Yamamoto M. Molecular mechanisms of the Keap1–Nrf2 pathway in stress response and cancer evolution. Genes Cells. 2011:16(2):123–140. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2010.01473.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yamashita Y, Ueyama T, Nishi T, Yamamoto Y, Kawakoshi A, Sunami S, Iguchi M, Tamai H, Ueda K, Ito T, et al. Ichinose, Nrf2-inducing anti-oxidation stress response in the rat liver—new beneficial effect of lansoprazole. PLoS One. 2014:9(5):e97419. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0097419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rada P, Rojo AI, Evrard-Todeschi N, Innamorato NG, Cotte A, Jaworski T, Tobón-Velasco JC, Devijver H, García-Mayoral MF, Van Leuven F, et al. Structural and functional characterization of Nrf2 degradation by the glycogen synthase kinase 3/β-TrCP axis. Mol Cell Biol. 2012:32(17):3486–3499. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00180-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Shinohara M, Ybanez MD, Win S, Than TA, Jain S, Gaarde WA, Han D, Kaplowitz N. Silencing glycogen synthase kinase-3beta inhibits acetaminophen hepatotoxicity and attenuates JNK activation and loss of glutamate-cysteine ligase and myeloid cell leukemia sequence 1. J BiolChem. 2010:285(11):8244–8255. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.054999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jiang Y, Bao H, Ge Y, Tang W, Cheng D, Luo K, Gong G, Gong R. Therapeutic targeting of GSK-3β enhances the Nrf2 antioxidant response and confers hepatic cytoprotection in hepatitis C. Gut. 2015:64(1):168–179. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-306043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chen Y, Pandiri I, Joe Y, Kim HJ, Kim SK, Park J, Ryu J, Cho GJ, Park JW, Ryterand SW, et al. Synergistic effects of cilostazol and probucol on ER stress-induced hepatic steatosis via heme oxygenase-1-dependent activation of mitochondrial biogenesis. Oxidative Med Cell Longev. 2016:3949813. doi: 10.1155/2016/3949813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wu CK, Lin JW, Wu LC, Chang CH. Risk of heart failure hospitalization associated with cilostazol in diabetes: a nationwide case-crossover study. Front Pharmacol. 2019:9:1467. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.01467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Feldman AM, Bristow MR, Parmley WW, Carson PE, Pepine CJ, Gilbert EM, Strobeck JE, Hendrix GH, Powers ER, Bain P. Effects of vesnarinone on morbidity and mortality in patients with heart failure. Vesnarinone Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1993:329(3):149–155. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199307153290301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Koh JS, Yi CO, Heo RW, Ahn JW, Park JR, Lee JE, Kim JH, Hwangand JY, Roh GS. Protective effect of cilostazol against doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy in mice. Free RadicBiol Med. 2015:89:54–61. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.07. 016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. AbuelezzandN SA. Hendawy, Insights into the potential antidepressant mechanisms of cilostazol in chronically restraint rats: impact on the Nrf2 pathway. Behav Pharmacol. 2018:29(1):28–40. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0000000000000335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fukao K, Shimada K, Hiki M, Kiyanagi T, Hirose K, Kume A, Ohsaka H, Matsumori R, Kurata T, Miyazakiand T, et al. Effects of calcium channel blockers on glucose tolerance, inflammatory state, and circulating progenitor cells in non-diabetic patients with essential hypertension: a comparative study between azelnidipine and amlodipine on glucose tolerance and endothelial function--a crossover trial (AGENT). Cardio vascDiabetol. 2011:10:79. doi: 10.1186/1475-2840-10-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lee DH, Park JS, Lee YS, Sung SH, Lee YH, Bae SH. The hypertension drug, verapamil, activates Nrf2 by promoting p62-dependent autophagic Keap1 degradation and prevents acetaminophen-induced cytotoxicity. BM Rep. 2017:50(2):91–96. doi: 10.5483/bmbrep.2017.50.2.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hafez HM, Ibrahim MA, Zedan MZ, Hassan M, Hassanein H. Nephroprotective effect of cilostazol and verapamil against thioacetamide-induced toxicity in rats may involve Nrf2/HO-1/NQO-1 signaling pathway. Toxicol Mech Methods. 2019:29(2):146–152. doi: 10.1080/15376516.2018.1528648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. National Research Council (US) Committee for the Update of the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. In: Guide for the care and use of laboratory animals. 8th ed. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2011 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kabil SL. Beneficial effects of cilostazol on liver injury induced by common bile duct ligation in rats: Role of SIRT1 signaling pathway. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2018:45(12):1341–1350. doi: 10.1111/1440-1681.13004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Marciniak S, Wnorowski A, Smolińska K, Walczyna B, Turski W, Kocki T, PaluszkiewiczandJ P. Kynurenic acid protects against thioacetamide-induced liver injury in rats. Anal Cell Pathol (Amst). 2018:1270483. doi: 10.1155/2018/1270483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yoshioka T, Kawada K, Shimada T, Mori M. Lipid peroxidation in maternal and cord blood and protective mechanism against activated-oxygen toxicity in the blood. Am J ObstetGynecol. 1979:135(3):372–376. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(79)90708-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ellman GL. Tissue sulfhydryl groups. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1959:82(1):70–77. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(59)90090-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Miranda KM, Espey MG, Wink DA. A rapid, simple spectrophotometric method for simultaneous detection of nitrate and nitrite. Nitric Oxide. 2001:5(1):62–71. doi: 10.1006/niox.2000.0319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mohamed MZ, Hafez HM, HassanandM M, Ibrahim A. PI3K/Akt and Nrf2/HO-1 pathways involved in the hepatoprotective effect of verapamil against thioacetamide toxicity in rats. Hum ExpToxicol. 2019:38(4):381–388. doi: 10.1177/0960327118817099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kadry MO, Abdel-Megeed RM, El-Meliegy E, Abdel-Hamid AZ. Crosstalk between GSK-3, c-Fos, NFκB, and TNF-α signaling pathways play an ambitious role in Chitosan Nanoparticles Cancer Therapy. Toxicol Rep. 2018:5:723–727. doi: 10.1016/j.toxrep.2018.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. VanGuilder HD, Vrana KE, Freeman WM. Twenty-five years of quantitative PCR for gene expression analysis. BioTechniques. 2008:44(5):619–626. doi: 10.2144/000112776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ishak K, Baptista A, Bianchi L, Callea F, De Groote J, Gudat F, Denk H, Desmet V, Korb G, MacSween RN. Histological grading and staging of chronic hepatitis. J Hepatol. 1995:22(6):696–699. doi: 10.1016/0168-8278(95)80226-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Saber S, Khalil RM, Abdo WS, NassifandE D. El-Ahwany, Olmesartan ameliorates chemically-induced ulcerative colitis in rats via modulating NFκB and Nrf-2/HO-1 signaling crosstalk. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2019:364:120–132. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2018.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bashandy SAE, Alaamer A, Moussaand SAA, Omara EA. Role of zinc oxide nanoparticles in alleviating hepatic fibrosis and nephrotoxicity induced by thioacetamide in rats. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2018:96(4):337–344. doi: 10.1139/cjpp-2017-0247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hajovsky H, Hu G, Koen Y, Sarma D, Cui W, Moore DS, Staudinger JL, Hanzlik RP. Metabolism and toxicity of thioacetamide and thioacetamide S-oxide in rat hepatocytes. Chem Res Toxicol. 2012:25(9):1955–1963. doi: 10.1021/tx3002719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ganesan K, Sukalingam K, Xu B, Solanumtrilobatum L. Ameliorate thioacetamide-induced oxidative stress and hepatic damage in albino rats. Antioxidants (Basel). 2017:6(3):68. doi: 10.3390/antiox6030068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kuramochi M, Izawa T, Pervin M, Bondoc A, Kuwamura M, Yamate J. The kinetics of damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) and toll-like receptors during thioacetamide-induced acute liver injury in rats. Exp Toxicol Pathol. 2016:68(8):471–477. doi: 10.1016/j.etp.2016.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Li X, Zhang H, Pan L, Zou H, Miao X, Cheng J, Wu Y. Puerarin alleviates liver fibrosis via inhibition of the ERK1/2 signaling pathway in thioacetamide-induced hepatic fibrosis in rats. Exp Ther Med. 2019:18(1):133–138. doi: 10.3892/etm.2019.7534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ahmed SM, Luo L, Namani A, Wang XJ, Tang X. Nrf2 signaling pathway: Pivotal roles in inflammation. Biochimicaetbiophysicaacta Mol Basis Dis. 2017:1863(2):585–597. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2016.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kaulmann A, Bohn T. Carotenoids, inflammation, and oxidative stress--implications of cellular signaling pathways and relation to chronic disease prevention. Nutr Res (New York, N Y). 2014:34(11):907–929. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2014.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bellezza I, Tucci A, Galli F, Grottelli S, Mierla AL, Pilolli F, Minelli A. Inhibition of NF-κB nuclear translocation via HO-1 activation underlies α-tocopheryl succinate toxicity. J Nutr Biochem. 2012:23(12):1583–1591. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2011.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ougolkov AV, Bone ND, Fernandez-Zapico ME, Kay NE, Billadeau DD. Inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase-3 activity leads to epigenetic silencing of nuclear factor kappaB target genes and induction of apoptosis in chroniclymphocytic leukemia B cells. Blood. 2007:110(2):735–742. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-12-060947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hoeflich KP, Luo J, Rubie EA, Tsao MS, Jin O, Woodgett JR. Requirement for glycogen synthase kinase-3beta in cell survival and NF-kappaB activation. Nature. 2000:406(6791):86–90. doi: 10.1038/3501757443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kotliarova S, Pastorino S, Kovell LC, Kotliarov Y, Song H, Zhang W, Bailey R, Maric D, Zenklusen JC, Lee J, et al. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 inhibition induces glioma cell death through c-MYC, nuclear factor-kappaB, and glucose regulation. Cancer Res. 2008:68(16):6643–6651. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Cortés-Vieyra R, Bravo-Patiño A, Valdez-Alarcón JJ, Juárez MC, Finlay BB, Baizabal-Aguirre VM. Role of glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta in the inflammatory response caused by bacterial pathogens. J Inflamm (Lond). 2012:9(1):23. doi: 10.1186/1476-9255-9-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hoesel B, Schmid JA. The complexity of NF-κB signaling in inflammation and cancer. Mol Cancer. 2013:12:86. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-12-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Abdel-Wahab BA, Ali F, Alkahtani SA, Alshabi AM, Mahnashi MH, Hassanein E. Hepatoprotective effect of rebamipide against methotrexate-induced hepatic intoxication: role of Nrf2/GSK-3β, NF-κβ-p65/JAK1/STAT3, and PUMA/Bax/Bcl-2 signaling pathways. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol. 2020:42(5):493–503. doi: 10.1080/08923973.2020.1811307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Salazar M, Rojo AI, Velasco D, Sagarra RM, Cuadrado AJ. Glycogen synthase kinase-3beta inhibits the xenobiotic and antioxidant cell response by direct phosphorylation and nuclear exclusion of the transcription factor Nrf2. Biol Chem. 2006:281(21):14841–14851. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513737200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Gao C, Holscher C, Liu Y, Li L. GSK3: a key target for the development of novel treatments for type 2 diabetes mellitus and Alzheimer's disease. Rev Neurosci. 2011:23(1):1–11. doi: 10.1515/rns.2011.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Grotterod I, Maelandsmo GM, Boye K. Signal transduction mechanisms involved in S100A4-induced activation of the transcription factor NF-kappaB. BMC Cancer. 2010:10:241. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Boye K, Grotterod I, Aasheim HC, Hovig E, Maelandsmo GM. Activation of NF-kappaB by extracellular S100A4: analysis of signal transduction mechanisms and identification of target genes. Int J Cancer. 2008:123(6):1301–1310. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Schmidt-Hansen B, Ornas D, Grigorian M, Klingelhofer J, Tulchinsky E, Lukanidin E, Ambartsumian N. Extracellular S100A4(mts1) stimulates invasive growth of mouse endothelial cells and modulates MMP-13 matrix metalloproteinase activity. Oncogene. 2004:23(32):5487–5495. doi: 10.1038/SJ.onc.1207720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Hsieh HL, Schafer BW, Weigleand B, Heizmann CW. S100 protein translocation in response to extracellular S100 are mediated by receptors for advanced glycation end products in human endothelial cells. Biochim Biophys Res Commun. 2004:316(3):949–959. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.02.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Pedersen KB, Andersen K, Fodstad O, Maelandsmo GM. Sensitization of interferon-gamma induced apoptosis in human osteosarcoma cells by extracellular S100A4. BMC Cancer. 2004:4:52. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-4-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Hassan M, Ibrahim MA, Hafez HM, Mohamed MZ, Zenhom NM, AbdElghany HM. Role of Nrf2/HO-1 and PI3K/Akt genes in the hepatoprotective effect of cilostazol. Curr Clin Pharmacol. 2019:14(1):61–67. doi: 10.2174/1574884713666180903163558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. El-Abhar H, Abd El Fattah MA, Wadie W, El-Tanbouly DM. Cilostazol disrupts TLR-4, Akt/GSK-3β/CREB, and IL-6/JAK-2/STAT-3/SOCS-3 crosstalk in a rat model of Huntington's disease. PLoS One. 2018:13(9):e0203837. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0203837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]