Abstract

Introduction

Although driver gene mutations have been believed to be mutually exclusive, some patients with NSCLC and concomitant EGFR mutations and EML4-ALK rearrangements have been reported. In this study, we reported a case of a patient with lung cancer who harbored both EGFR mutation and the EML4-ALK rearrangement after acquiring resistance to the EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor treatment. EGFR-mutant and ALK fusion proteins were detected in the same tumor cells through immunohistochemical analysis. Investigation of the molecular mechanisms of concomitant EGFR mutation and the EML4-ALK rearrangement in the same tumor cell can help discover an appropriate treatment for these patients.

Methods

PC-9 cells, expressing EGFR exon 19 deletion, were transfected with EML4-ALK variant 3a (v3a) and variant 3b (v3b) separately and selected, and the effect of EGFR and ALK inhibitors was evaluated in vitro and in vivo.

Results

PC-9_v3a-gef and PC-9_v3b-gef cells were resistant to gefitinib and ALK inhibitors alone, but ALK inhibitors enhanced gefitinib-induced cytotoxicity. In animal studies, gefitinib completely inhibited the tumor growth in PC-9_vector cells but not in PC-9_v3a-gef and PC-9_v3b-gef cells. A combination of ALK inhibitor and gefitinib was found to be more potent than gefitinib alone in PC-9_v3a-gef and PC-9_v3b-gef cells. Furthermore, combination treatment with osimertinib and ceritinib caused a decrease in liver tumor size of the patient with liver metastases.

Conclusions

Our data suggest that combination treatment with EGFR and ALK inhibitors can be a therapeutic strategy for treating NSCLC with concomitant EGFR mutation and EML4-ALK rearrangement.

Keywords: EGFR, EML4-ALK, Lung cancer, EGFR-TKI, ALK inhibitor

Introduction

Oncogenic driver mutations result in abnormal activation of signaling pathways that contribute to cancer initiation.1 Detection and inhibition of oncogenic driver mutations improve the efficacy of therapy for NSCLC.2 Several oncogenic driver mutations such as mutation of the EGFR and fusion of the EML4-ALK genes have been identified in NSCLC.2,3 Studies have reported that EGFR mutations and EML4-ALK fusions are mutually independent.4, 5, 6 Moreover, the coexistence of the EGFR mutations and EML4-ALK fusions has been reported in lung cancers.7,8 Furthermore, the coexistence of these two proteins was detected in the same tumor cell through immunohistochemical analysis.8

EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) such as gefitinib, erlotinib, and afatinib are the standard therapies for patients with advanced NSCLC with tumor cells carrying specific EGFR mutations.9 All patients eventually develop acquired resistance to first- or second-generation EGFR TKIs, and new-generation EGFR T790M inhibitors such as osimertinib overcome T790M-mediated resistance to first-line EGFR TKI therapy.10 Similarly, ALK inhibitors such as crizotinib and ceritinib are effective against NSCLC with the EML4-ALK fusion gene.11 Identification of the real driver gene is essential for physicians to determine appropriate treatments for patients. Nevertheless, in patients with tumor cells carrying both EGFR mutation and EML4-ALK fusion, whether EGFR is the major driver in the cancer cells is uncertain. In addition, the expression of EML4-ALK rearrangement may be associated with EGFR TKI resistance.12 Therefore, the efficacies of EGFR TKIs and ALK inhibitors remain elusive in NSCLC harboring both EGFR mutation and EML4-ALK fusion.

In this study, we reported a case of a patient with lung cancer with tumor carrying both mutant EGFR and EML4-ALK fusion genes. We explored the effect of EGFR TKI and ALK inhibitors on lung cancer cells with concurrent EGFR mutation and EML4-ALK fusion both in vitro and in vivo. We further identified that a combination treatment with EGFR TKIs and ALK inhibitors is a potential strategy for NSCLC with concomitant EGFR mutations and EML4-ALK fusion.

Materials and Methods

Patient With Lung Cancer and Gene Sequencing

A patient was diagnosed with having EGFR-mutant advanced NSCLC and was treated at the National Taiwan University Hospital. The treatment course was recorded. A liver biopsy was performed on progression to an EGFR T790M inhibitor. Targeted sequencing of a panel of 35 cancer-related genes and four lung cancer-related fusion genes, the ACT-Drug panel, was performed by ACT genomics (Taipei City, Taiwan). The patient’s medical record was reviewed. The use of patient data, including a waiver of informed consent from patients who were expired, was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the National Taiwan University Hospital (NTUH REC 201612136RINC).

Immunochemistry Study

Tissue sections (4 μm) were deparaffinized and rehydrated. Immunohistochemical analysis was performed using a Ventana BenchMark XT Autostainer (Ventana, Tucson, AZ). The slides were allowed to react with an antibody specific for ALK (D5F3) CDx Assay (Ventana) and anti-EGFR (E746-A750del specific) antibody (clone 6B6, 1:150; Cell Signaling Technology). The results were evaluated by a pulmonary pathologist (Dr. Min-Shu Hsieh).

Cell Lines and Drugs

PC-9 is a human lung adenocarcinoma cell line with EGFR exon 19 deletion mutation.13 PC-9 cells were cultured in Roswell Park Memorial Institute 1640 medium (HyClone, Logan, UT) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. Gefitinib, crizotinib, alectinib, MK2206, and selumetinib were purchased from Selleckchem (Houston, TX).

Construction of EML4-ALK Variant 3 and Cell Transfection

The coding sequence for EML4-ALK variant 3a (v3a) or variant 3b (v3b) was amplified from the total complementary DNA (cDNA) of the H2228 cells. The cDNA for EML4-ALK v3a or v3b was cloned into the pcDNA 3.3-TOPO vector (Invitrogen). The empty pcDNA 3.3-TOPO vector, pcDNA 3.3-TOPO-EML4-ALK v3a, and pcDNA 3.3-TOPO-EML4-ALK v3b were transfected into the PC-9 cells by using the Xfect transfection reagent (Clontech Laboratories, Mountain View, CA), and the cells were considered transiently expressing cells. To establish cells stably expressing transfected genes, the cells were further incubated in 500 mg/mL G418 (Geneticin, Gibco, Grand Island, NY), and the selected cells were considered stably expressing cells. To obtain EML4-ALK v3a or v3b functional cells, PC-9 cells with a stable expression of EML4-ALK v3a or v3b were incubated with 1 μM gefitinib for 1 week, and the selected cells were expanded and used in further studies.

Cell Viability Assays

Cell viability on drug treatment was determined using the sulforhodamine B assay as described previously.14 Percentages of cell viability were calculated by dividing the absorbance values of drug-treated cells by those of untreated cells.

Western Blotting

Western blotting was performed as described previously.13 Primary antibodies used for immunoblot analyses were as follows: α-tubulin (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA); ALK and phospho-ALK specific for Tyr1078, Tyr1278, Tyr1282/1283, Tyr1586, and Tyr1604 (Cell Signaling Technology), Akt, phospho-Akt (Ser473); extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK); phospho-ERK (Cell Signaling Technology); EGFR; phospho-EGFR (Tyr1068); HER2; phospho-HER2 (Tyr1221/1222); HER3; phospho-HER3 (Tyr1289) (Cell Signaling Technology); poly (adenosine diphosphate-ribose) polymerase (PARP); caspase-3; and caspase-9 (Cell Signaling Technology).

Xenograft Mouse Model

The 1 × 106 cells were subcutaneously injected into the back of 6-week-old male Balb/c nude mice. The length and width of the tumors were measured using an electronic caliper, and the tumor volume was determined as (length × width2)/2. When tumors grew to 150 mm3, mice were randomized into four groups and were administered vehicle, gefitinib (50 mg/kg once daily), alectinib (20 mg/kg once daily), or gefitinib plus alectinib. Gefitinib was suspended in 0.05% Tween 80 solution. Alectinib was suspended in a mixture of 30% polyethylene dicol 400, 0.5% Tween 80, and 5% propylene glycol solution. These animals were maintained in individually ventilated cages according to the guidelines of Guide for The Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. The use of animals was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the National Taiwan University College of Medicine, Taipei, Taiwan.

Statistical Analyses

Animal experimental data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism software. Statistical differences were determined using the Mann-Whitney U nonparametric test. p values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

A Patient With Lung Cancer With Tumor Cells Carrying Both Mutant EGFR Gene and EML4-ALK Fusion Benefited From Combination Therapies

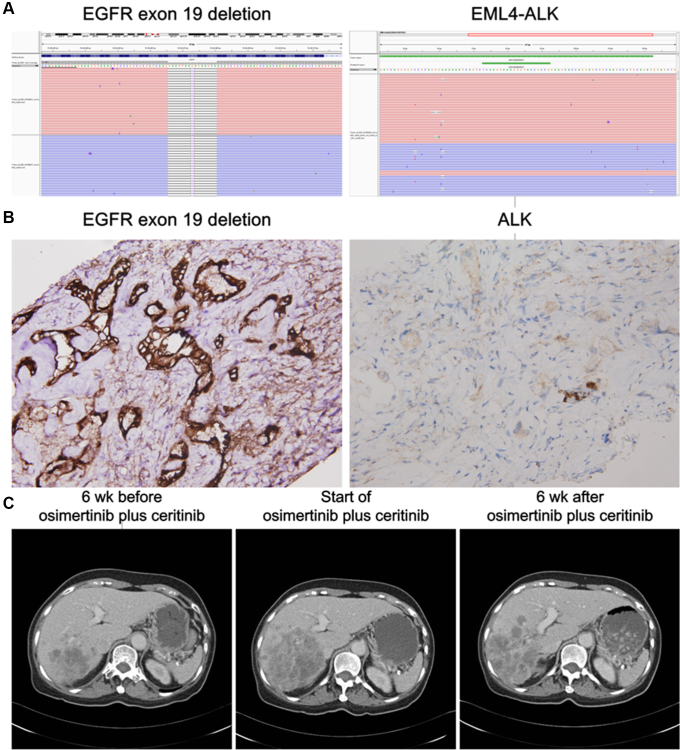

A 68-year-old woman with no smoking history had lung adenocarcinoma with brain, lung, and liver metastases; according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging version 7, the tumor stage was cT1bN3M1b. EGFR exon 19 deletion (E746_A750 deletion) was identified in the tumor, and result of the immunohistochemical analysis of the ALK protein was negative. She had received anticancer therapies, including afatinib and carboplatin plus pemetrexed. A biopsy performed on progression to afatinib revealed EGFR exon 19 deletion plus T790M-mutant adenocarcinoma. She was enrolled in a clinical trial of an EGFR T790M-specific inhibitor. Partial response was noted which persisted for 11 months until the development of progression to the liver. Result of a genetic analysis of the tumor from the liver revealed the presence of four copies of the EGFR gene, EGFR exon 19 deletion plus T790M mutation, TP53 mutation, and type 5 EML4-ALK fusion (Fig. 1A). Immunohistochemistry confirmed the coexpression of ALK and EGFR exon 19 deletion (E746_A750 deletion) proteins in the tumor cells (Fig. 1B). Ceritinib, an ALK inhibitor, was administered for 1 week, and a computed tomography (CT) scan revealed disease progression. She received an osimertinib plus ceritinib therapy. A CT scan 6 weeks after the therapy suggested a modest decrease in the size of the liver tumors (Fig. 1C). Unfortunately, a CT scan 12 weeks after osimertinib plus ceritinib suggested progression of a liver tumor which was different from the liver lesion we took from biopsy. The patient expired 6 months after start of osimertinib plus ceritinib.

Figure 1.

Emergence of the EML4-ALK fusion gene in a patient with EGFR-mutant advanced NSCLC. (A) Deep sequencing result of the progressive tumor suggests deletion of EGFR exon 19 (E746_A750del) and fusion of EML4 (exon 2) and ALK (exon 20). (B) Immunohistochemical analysis results confirmed the expression of mutated EGFR (E746_A750del) and ALK proteins in the progressive tumor. (Original magnification: 400×) (C) Computed tomography images of the liver lesions on progression to an EGFR T790M inhibitor. Images were obtained 6 weeks before progression, start of osimertinib plus ceritinib treatment, and 6 weeks after osimertinib plus ceritinib treatment.

PC-9 Cells That Stably Expressed the EML4-ALK Fusion Gene Were Resistant to Gefitinib

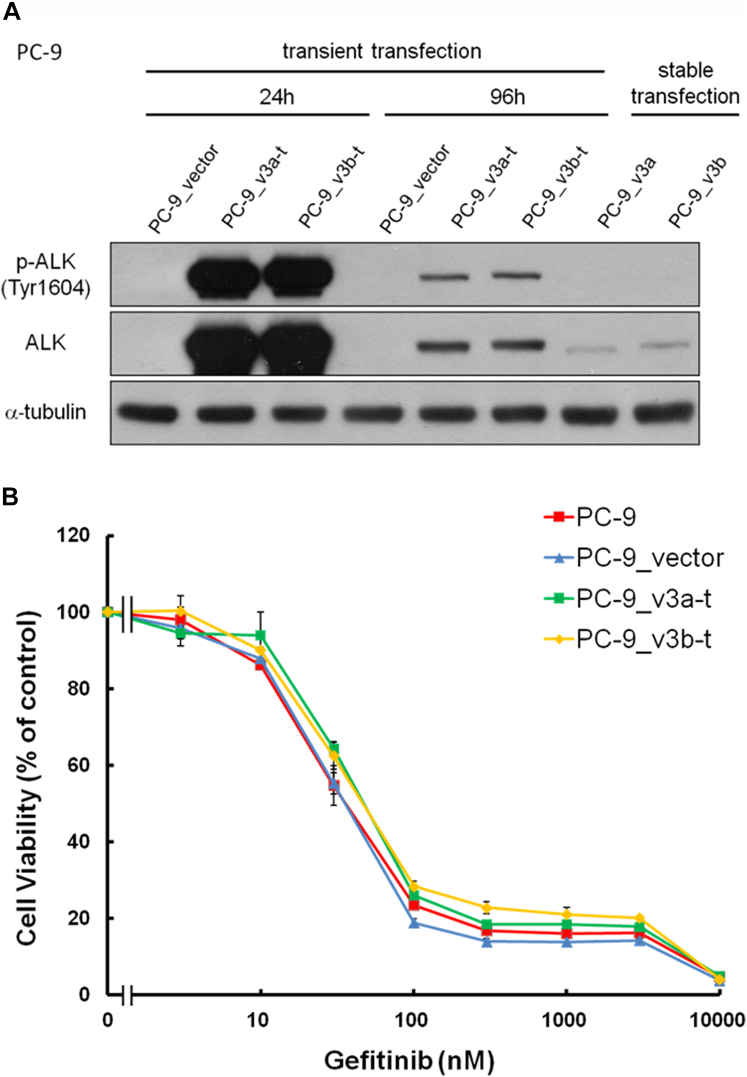

To explore whether the cancer cells were simultaneously driven by both genes, we expressed the EML4-ALK fusion gene in the PC-9 lung cancer cells carrying EGFR exon 19 deletion mutation. We first transiently expressed the EML4-ALK fusion v3a (PC-9_v3a-t) or v3b (PC-9_v3b-t) in the PC-9 cells (Fig. 2A). No difference was observed in cell viability of the PC-9 cells and cells transiently expressing the EML4-ALK fusion v3a (PC-9_v3a-t) or v3b (PC-9_v3b-t) at various concentrations of the EGFR inhibitor gefitinib (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

Transient ectopic expression of EML4-ALK v3a and v3b in the PC-9 cells. (A) Expression of ALK and p-ALK in the PC-9 cells after 24 and 96 hours of infection with pcDNA 3.3-TOPO vector (PC-9_vector), pcDNA 3.3-TOPO-EML4-ALK v3a (PC-9_v3a-t), and pcDNA 3.3-TOPO-EML4-ALK v3b (PC-9_v3b-t). Cells stably expressing EML4-ALK v3a and v3b were established by incubating the cells with G418 and were named as PC-9_v3a and PC-9_v3b, respectively. (B) Cell viability of the PC-9, PC-9_vector, PC-9_v3a-t, and PC-9_v3b-t cells was tested after treatment with increasing gefitinib concentrations. Values are presented as means ± SD for three independent experiments. v3a, variant 3a; v3b, variant 3b. p-ALK, phospho-ALK.

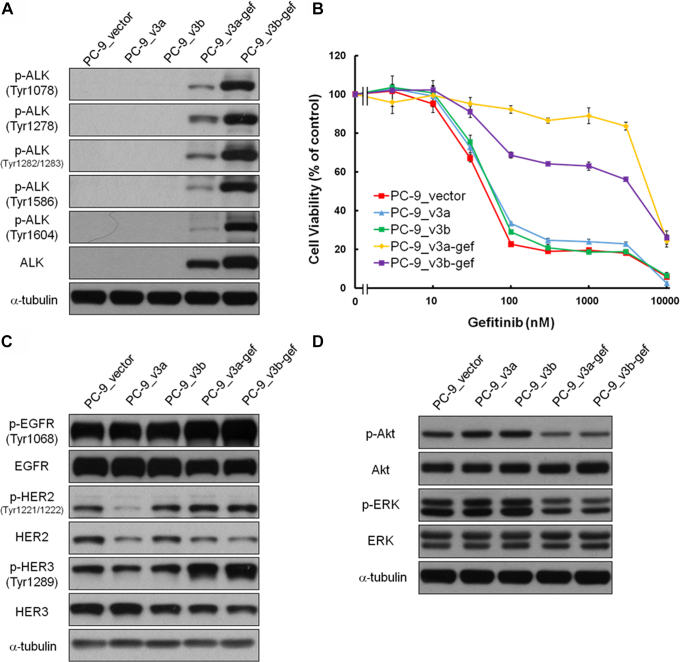

We then established the PC-9 cells stably expressing EML4-ALK v3a and EML4-ALK v3b by incubating the cells with G418. After G418 selection, we obtained PC-9_v3a and PC-9_v3b cells that had low expression of EML4-ALK v3a and EML4-ALK v3b proteins, respectively (Figs. 2A and 3A). Localization of phospho-ALK was not observed in PC-9_v3a or PC-9_v3b cells (Figs. 2A and 3A), and cell viability on gefitinib treatment was similar to that of cells transfected with the vector (PC-9_vector) (Fig. 3B). We incubated the PC-9_v3a and PC-9_v3b cells with 1 μM of gefitinib and a few of the cells re-expanded after 2 weeks of the incubation. Notably, the gefitinib-treated cells, the PC-9_v3a-gef and PC-9_v3b-gef cells, were resistant to gefitinib (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

Characterization of the PC-9 cells stably expressing EML4-ALK v3a and v3b. (A) Expression of ALK and phospho-ALK in the PC-9_vector, PC-9_v3a, PC-9_v3b, PC-9_v3a-gef, and PC-9_v3b-gef cells. The PC-9_v3a-gef and PC-9_v3a-gef cells were derived from the PC-9_v3a and PC-9_v3b cells through incubation with gefitinib for 2 weeks. (B) Cell viability of the PC-9_vector, PC-9_v3a, PC-9_v3b, PC-9_v3a-gef, and PC-9_v3b cells was tested at various concentrations of gefitinib. Values are presented as means ± SD for three independent experiments. (C) Expression of EGFR, HER2, and HER3 and their phosphorylated forms in the cells. (D) Expression of Akt and ERK and their phosphorylated forms in the cells. v3a, variant 3a; v3b, variant 3b. p-Akt, phosphor-Akt; p-ALK, phospho-ALK; p-EGFR, phospho-EGFR; p-ERK, phospho-ERK; p-HER2, phospho-HER2; p-HER3, phospho-HER.3.

We attempted to characterize the PC-9_v3a-gef and PC-9_v3b-gef cells. We observed the ALK and phospho-ALK proteins in the PC-9_v3a-gef and PC-9_v3b-gef cells (Fig. 3A). No difference was observed in the expression of EGFR, HER2, and HER3, including their phosphorylated forms, in the PC-9_vector, PC-9_v3a-gef, and PC-9_v3b-gef cells (Fig. 3C). Stable expression of the EML4-ALK v3a or v3b did not influence the phosphorylation of downstream signals of EGFR, including Akt and ERK (Fig. 3D).

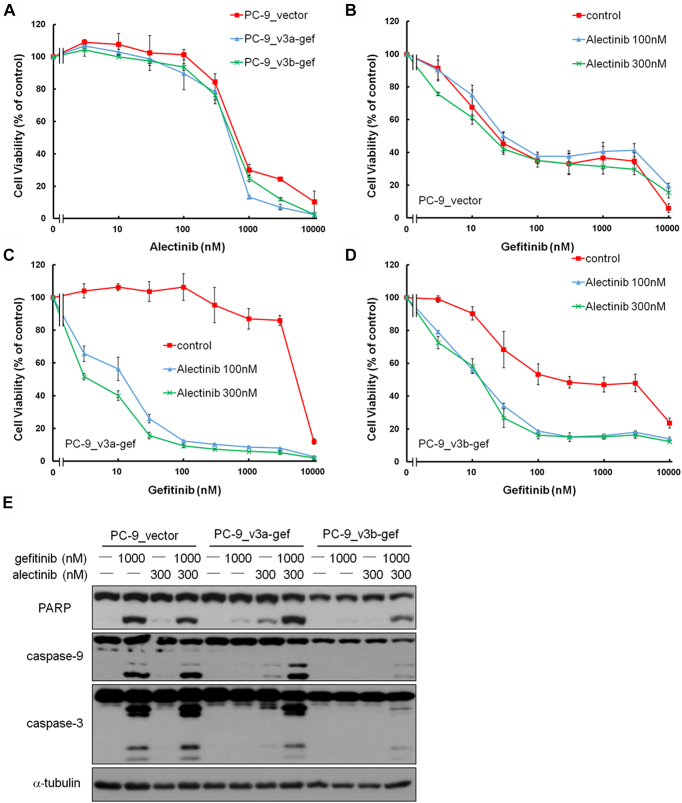

A Combination of Gefitinib and Alectinib Inhibited Growth and Induced Apoptosis of EML4-ALK–Expressing PC-9 Cells

Because the PC-9_v3a-gef and PC-9_v3b-gef cells were resistant to gefitinib, we explored the role of the EML4-ALK fusion gene in these cells. No difference was observed in cell viability of the PC-9_vector, PC-9_v3a-gef, and PC-9_v3b-gef cells on treatment with various concentrations of ALK inhibitors, alectinib, or crizotinib (Fig. 4A and Supplementary Fig. 1A). The sensitivity of the PC-9_vector cells to gefitinib was not influenced by exposure to alectinib (100 or 300 nM) or crizotinib (100 or 300 nM) (Fig. 4B and Supplementary Fig. 1B). We observed a remarkable decrease in the cell viability of both the PC-9_v3a-gef and PC-9_v3b-gef cells when the cells were cotreated with gefitinib and alectinib or crizotinib (Fig. 4C and D and Supplementary Fig. 1C and D). The findings suggested that the EML4-ALK fusion gene is responsible for the resistance to gefitinib in both the PC-9_v3a-gef and PC-9_v3b-gef cells.

Figure 4.

Effect of the ALK inhibitor alectinib on sensitization of the PC-9_v3a-gef and PC-9_v3b-gef cells to gefitinib. (A) Cell viability of the PC-9_vector, PC-9_v3a-gef, and PC-9_v3b-gef cells on treatment with various concentrations of alectinib. Effect of the combination treatment of alectinib and gefitinib on viability of the (B) PC-9_vector cells, (C) PC-9_v3a-gef cells, and (D) PC-9_v3b-gef cells. Values are presented as means ± SD for three independent experiments. (E) Expression of PARP, caspase-9, and caspase-3 and their cleaved forms in the PC-9_vector, PC-9_v3a-gef, and PC-9_v3b-gef cells on gefitinib, or alectinib alone, or gefitinib plus alectinib treatment. v3a, variant 3a; v3b, variant 3b.

We then evaluated whether the change in cell viability was due to apoptosis induction. Exposure to gefitinib (1000 nM) but not alectinib (300 nM) induced cleaved forms of PARP, caspase-9, and caspase-3 in the PC-9_vector cells (Fig. 4E). Gefitinib (1000 nM) or alectinib (300 nM) alone induced modest amounts of cleaved forms of PARP, caspase-9, and caspase-3 in the PC-9_v3a-gef and PC-9_v3b-gef cells. A combination of gefitinib (1000 nM) and alectinib (300 nM) resulted in a remarkable elevation of the cleaved forms of PARP, caspase-9, and caspase-3 in both cells (Fig. 4E). These findings indicated that the PC-9_v3a-gef and PC-9_v3b-gef cells underwent apoptosis when they were exposed to a combination of EGFR inhibitor and ALK inhibitor.

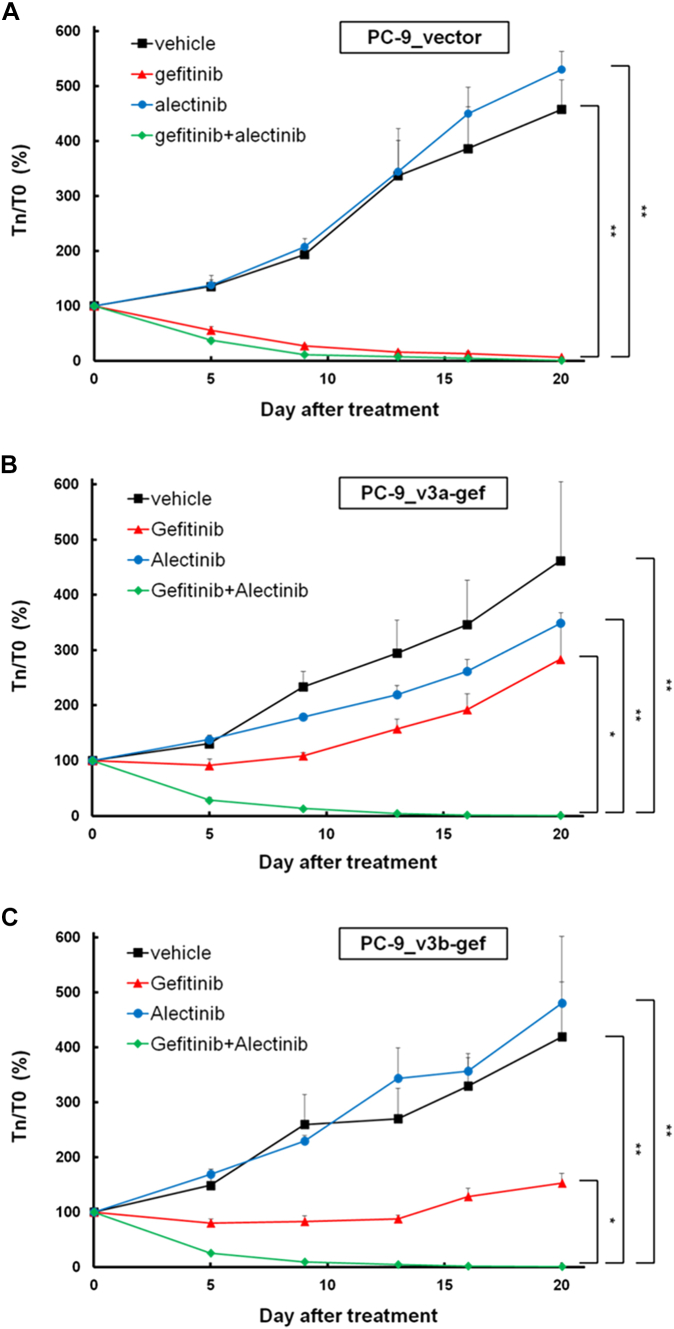

A Combination of Gefitinib and Alectinib Inhibited the Growth of EML4-ALK–Expressing PC-9 Xenografts

We evaluated the effects of EGFR TKI and ALK inhibitors in vivo. The growth of PC-9_vector xenografts was attenuated by gefitinib or gefitinib plus alectinib treatment but not by alectinib alone (Fig. 5A). Furthermore, the growth of PC-9_v3a-gef and PC-9_v3b-gef xenografts was inhibited by gefitinib plus alectinib treatment but not by gefitinib or alectinib alone (Fig. 5B and C).

Figure 5.

Effect of gefitinib and/or alectinib on xenograft models. (A) PC-9_vector xenografts, (B) PC-9_v3a-gef xenografts, and (C) PC-9_v3b-gef xenografts. Values are presented as means ± SEM (∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.005; n = 4). T0, tumor volume before drug treatment; Tn, tumor on day nth of drug treatment; v3a, variant 3a; v3b, variant 3b.

Complicated Downstream Signaling of EML4-ALK

We explored the difference in signaling pathways between the PC-9 cells with and without EML4-ALK translocation. Phosphorylation of EGFR but not ALK was inhibited by gefitinib in the PC-9_v3a-gef and PC-9_v3b-gef cells (Fig. 6A). Akt and ERK were the two dominant downstream targets of EGFR and EML4-ALK. The EGF-induced ERK phosphorylation was inhibited by gefitinib alone in both the PC-9_v3a-gef and PC-9_v3b-gef cells in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 6B). Nevertheless, the inhibitory effect of gefitinib on EGF-induced phosphorylation of Akt in the PC-9_v3a-gef and PC-9_v3b-gef cells was weak compared with that in the PC-9_vector cells (Fig. 6B and C). Alectinib treatment inhibited ALK phosphorylation in both the PC-9_v3a-gef and PC-9_v3b-gef cells (Fig. 6C). Nevertheless, phosphorylations of Akt and ERK were not influenced by alectinib alone. A combination of gefitinib and alectinib inhibited Akt phosphorylation to a greater extent in the PC-9_v3a-gef and PC-9_v3b-gef cells (Fig. 6C). STAT3 phosphorylation was not influenced by gefitinib, alectinib, or their combination in both the PC-9_v3a-gef and PC-9_v3b-gef cells (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Figure 6.

Characterization of the PC-9_v3a-gef and PC-9_v3b-gef cells. Effect of various concentrations of gefitinib on (A) expression of ALK and EGFR and their phosphorylated forms and (B) expression of Akt and ERK and their phosphorylated forms. (C) Expression of ALK, EGFR, Akt, and ERK and their phosphorylated forms on gefitinib, or alectinib alone, or gefitinib plus alectinib treatment. All the cells were incubated in serum-free media for 3 hours, treated with gefitinib, or alectinib alone, or gefitinib plus alectinib at various concentrations for 1 hour, and then stimulated with 20 ng/mL EGF for 10 minutes. v3a, variant 3a; v3b, variant 3b. p-Akt, phosphor-Akt; p-ALK, phospho-ALK; p-EGFR, phospho-EGFR; p-ERK, phospho-ERK.

We next evaluated whether Akt or ERK inhibition influenced gefitinib sensitivity in the EML4-ALK stably expressing cells. No difference was observed in cell viability of the PC-9_vector, PC-9_v3a-gef, and PC-9_v3b-gef cells in response to Akt inhibitor, MK2206 (Supplementary Fig. 3A). MK2206 or selumetinib (MEK1/2 inhibitor) modestly sensitized the PC-9_v3a-gef and PC-9_v3b-gef cells to gefitinib, resulting in a decrease in cell viability (Supplementary Fig. 3B and C). The combination of MK2206 and selumetinib sensitized the PC-9_v3b-gef cells but not the PC-9_v3a-gef cells to gefitinib (Supplementary Fig. 3B and C). Our findings suggested that the EML4-ALK fusion gene might have multiple downstream signals. Blocking only one of these downstream pathways cannot increase the sensitivity of the tumor cells to gefitinib in NSCLC with concomitant EGFR mutation and EML4-ALK translocation.

Discussion

We reported that both the mutant EGFR and EML4-ALK fusion genes drove the cancer cells. We identified a patient with advanced EGFR-mutant NSCLC, whose tumor on progression after EGFR inhibitor treatment carried a fusion of the EML4-ALK gene. The patient with lung cancer with liver metastases exhibited a modest decrease in size of liver tumors after receiving osimertinib plus ceritinib. We further found, in vitro and in vivo, the efficacy of the combination therapy of an EGFR inhibitor and an ALK inhibitor in EGFR-mutant lung cancer cells with the EML4-ALK fusion gene.

With few exceptions, oncogenic driver mutations in nonsquamous cell NSCLC are generally mutually exclusive.15,16 Guibert et al.17 reported the detection of multiple genetic alterations involving driver mutations in 165 of 17,826 (0.93%) untreated NSCLC samples. Concomitant EML4-ALK and EGFR mutation have been reported in lung cancers.18 In tumors harboring multiple potential driver mutations, little is known whether the concomitant mutations are essential or one mutation is dominant for cancer cell growth. In the patient-derived cancer cell line harboring both EGFR exon 19 deletion and PCBP2-BRAF fusion protein, Piotrowska et al.19 reported that unlike osimertinib or BRAF inhibitors, the MEK1/2 inhibitor trametinib alone was able to abolish cell growth. Schmid et al.20 reported five patients with the EGFR-mutant de novo and ALK-positive NSCLCs. Partial responses were observed in four of five patients who received the EGFR inhibitor or ALK inhibitor monotherapy, which was supportive of a single mutation that was dominant in tumors with de novo concomitant EGFR mutation and ALK fusion. In another study, Yang et al.8 described that the phosphorylation levels of EGFR and ALK in tumors harboring both EGFR mutation and EML4-ALK translocation responded to EGFR TKI and crizotinib. In our patient, the in vitro findings revealed that either an EGFR inhibitor or an ALK inhibitor alone was unable to inhibit cancer cell growth. In selected situations, cancer cells may be driven by multiple potential oncogenic drivers.

We explored the signaling pathways relating to the EML4-ALK–induced resistance to the EGFR inhibitors. The molecular mechanism of the EML4-ALK fusion protein is complicated, and it has been generally believed that the PI3K/Akt, JAK/STAT3, PLCγ, and MAPK cascades are the downstream signal pathways of the ALK protein, and these pathways may mediate the malignant behavior of the ALK-driven cancer cells (reviewed by Bayliss et al.21). The downstream signal of the EML4-ALK may be content dependent.22 Several EML4-ALK variant proteins exist, and different EML4-ALK variant proteins have different intracellular localizations and interact with different proteins. EML4-ALK variant 1, variant 2, and variant 5a localized diffusely in the cytoplasm, whereas variant 3 colocalized with the microtubules in the cytoplasm.23,24 We reported that the phosphorylation of Akt and ERK was regulated by EGFR signaling but not by ALK signaling in the PC-9_v3a-gef and PC-9_v3b-gef lung cancer cells (Fig. 6). Nevertheless, the PC-9_v3a-gef and PC-9_v3b-gef cells were resistant to gefitinib. The combination of Akt and the MEK inhibitor did not sensitize the PC-9_v3a-gef and PC-9_v3b-gef cells to gefitinib (Supplementary Fig. 3B and C). Our findings suggested that multiple molecular cascades may drive the ALK signals in the PC-9_v3a-gef and PC-9_v3b-gef cells. Therefore, blocking a single pathway cannot increase the sensitivity of the tumor cells to gefitinib in NSCLC with concomitant EGFR mutation and EML4-ALK translocation.

Mechanisms of acquired resistance to EGFR inhibitors have been widely studied. Although osimertinib is effective in the treatment of acquired resistance resulting from the acquired EGFR T790M mutation, which is responsible for approximately 50% of resistance to first- or second-generation EGFR inhibitors, few treatment strategies for treating acquired resistance to EGFR T790M mutation exist. Targeting the acquired amplification of the MET gene has been widely studied clinically. In the phase 3 study, to evaluate the efficacy of the MET monoclonal antibody onartuzumab in patients with MET-expressing advanced NSCLC, the survival rate was shorter in patients with EGFR-mutant lung cancer who received onartuzumab plus erlotinib.25 In the phase 1/2 study on the MET inhibitor capmatinib (INC280) plus gefitinib in patients with EGFR-mutant lung cancer, after the failure of EGFR inhibitors, a response rate of 47% and a median progression-free survival of 5.5 months were observed among patients with tumor cells harboring more than six copies of the MET gene.26 Because amplification of the MET gene is observed only in approximately 5% of progressive tumors,27 an unmet need for exploring clinically relevant treatment strategies for the acquired resistance to first- or second-generation EGFR inhibitors still exists. In addition, mechanisms of resistance to osimertinib have been reported,19,28,29 and strategies to overcome the resistance are mostly under development. According to our knowledge, this is the first time the efficacy of the combination therapy of an EGFR inhibitor and an ALK inhibitor in a patient with NSCLC with tumor cells harboring both an EGFR mutation and a EML4-ALK fusion gene has been reported. A comprehensive genomic study of tumors on progression to EGFR inhibitors may guide the selection of treatment in patients with advanced EGFR-mutant lung cancer.

In our patient, we observed the existence of stable disease in response to osimertinib plus ceritinib. The EML4-ALK fusion in the patient was the EML4-ALK variant 5. It has been reported that the progression-free survival owing to ALK inhibitors and chemotherapies was shorter in patients with EML4-ALK variant 3 lung cancers, including their overall survival.30,31 In addition, the Ba/F3 cells transformed by the EML-ALK variant 3 or 5a proteins were less sensitive to ALK inhibition than cells transformed by the EML4-ALK variant 1 or 2.31 The difference in the sensitivity may be due to a difference in protein (EML4-ALK) stability in the cells.23 The stable disease noted in our patient was compatible with clinical and in vitro findings reported previously. In addition, a CT scan taken 12 weeks after start of osimertinib plus ceritinib suggested progression of a liver tumor different from the one we took from biopsy. Considering the potential intrapatient heterogeneity of the tumors in a patient with heavily pretreated EGFR-mutant lung cancer, we do not exclude the possibility that the progressive lesion may carry resistant mechanism other than the concomitant EML4-ALK rearrangement.

Notably, we observed that the PC-9 cells that stably expressed the EML4-ALK variant 3 were sensitive to gefitinib (PC-9_v3a and PC-9_v3b cells; Fig. 3B) unless they were incubated with gefitinib for 1 week and acquired resistance to gefitinib (PC-9_v3a-gef and PC-9_v3b-gef cells; Fig. 3B). The establishment of cancer cells resistant to a drug usually requires months (reviewed by McDermott et al.32); however, the clinical relevance of the resistant cells in vitro is often questionable. The process of incubating EGFR-mutant lung cancer cells in escalating concentrations of EGFR inhibitors in vitro to develop resistance against EGFR inhibitors has been found to occur in months.13,33 Nevertheless, for the first time, we found that drug resistance can be induced in cancer cells by incubation with the drug for a short period of time. Our model may aid future research on drug resistance.

To conclude, both mutant EGFR and the EML4-ALK fusion gene drive mutations in patients with advanced EGFR-mutant lung cancer on progression to EGFR inhibitor resistance. Targeting mutant EGFR and ALK is a novel treatment strategy for treating NSCLC harboring EGFR mutation and EML4-ALK translocation.

CRediT Authorship Contribution Statement

Ming-Hung Huang: Methodology, Validation, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing.

Jih-Hsiang Lee: Validation, Data curation, Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing.

Pei-Shan Hung: Methodology.

James Chih-Hsin Yang: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing—review and editing.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grants from the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan, Republic of China (grant number MOST 107-2314-B-002-220-MY3).

Footnotes

Disclosure: Dr. Lee reports having advisory consultation for Novartis, Takeda, and Eli Lilly. Dr. Yang reports receiving personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Bayer, Roche/Genentech, Chugai Pharmaceutical, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Pfizer, Novartis, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Ono Pharmaceuticals, AstraZeneca, ACT Genomics, Merck Serono, Celgene, Yuhan Pharmaceuticals, Daiichi Sankyo, Hansoh Pharmaceuticals, Takeda Pharmaceuticals, Blueprint Medicines, and G1 Therapeutics, outside of the submitted work. Drs. Huang and Hung declare no conflict of interest.

Cite this article as: Huang MH, Lee JH, Hung PS, et al. Potential therapeutic strategy for EGFR-mutant lung cancer with concomitant EML4-ALK rearrangement—combination of EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors and ALK inhibitors. JTO Clin Res Rep. 2022;3:100405.

Note: To access the supplementary material accompanying this article, visit the online version of the JTO Clinical and Research Reports at www.jtocrr.org and at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtocrr.2022.100405.

Supplementary Data

References

- 1.Stratton M.R., Campbell P.J., Futreal P.A. The cancer genome. Nature. 2009;458:719–724. doi: 10.1038/nature07943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pao W., Girard N. New driver mutations in non-small-cell lung cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:175–180. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70087-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hirsch F.R., Suda K., Wiens J., Bunn P.A. New and emerging targeted treatments in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Lancet. 2016;388:1012–1024. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31473-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wong D.W., Leung E.L., So K.K., et al. The EML4-ALK fusion gene is involved in various histologic types of lung cancers from nonsmokers with wild-type EGFR and KRAS. Cancer. 2009;115:1723–1733. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu S.G., Kuo Y.W., Chang Y.L., et al. EML4-ALK translocation predicts better outcome in lung adenocarcinoma patients with wild-type EGFR. J Thorac Oncol. 2012;7:98–104. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3182370e30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang X., Zhang S., Yang X., et al. Fusion of EML4 and ALK is associated with development of lung adenocarcinomas lacking EGFR and KRAS mutations and is correlated with ALK expression. Mol Cancer. 2010;9:188. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-9-188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee T., Lee B., Choi Y.L., Han J., Ahn M.J., Um S.W. Non-small cell lung cancer with concomitant EGFR, KRAS, and ALK mutation: clinicopathologic features of 12 cases. J Pathol Transl Med. 2016;50:197–203. doi: 10.4132/jptm.2016.03.09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang J.J., Zhang X.C., Su J., et al. Lung cancers with concomitant EGFR mutations and ALK rearrangements: diverse responses to EGFR-TKI and crizotinib in relation to diverse receptors phosphorylation. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:1383–1392. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-0699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diaz-Serrano A., Gella P., Jimenez E., Zugazagoitia J., Paz-Ares Rodríguez L. Targeting EGFR in lung cancer: current standards and developments. Drugs. 2018;78:893–911. doi: 10.1007/s40265-018-0916-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mok T.S., Wu Y.L., Ahn M.J., et al. Osimertinib or platinum-pemetrexed in EGFR T790M-positive lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:629–640. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1612674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fruh M., Peters S. EML4-ALK variant affects ALK resistance mutations. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:1257–1259. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.77.2764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shaw A.T., Yeap B.Y., Mino-Kenudson M., et al. Clinical features and outcome of patients with non-small-cell lung cancer who harbor EML4-ALK. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4247–4253. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.6993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang M.H., Lee J.H., Chang Y.J., et al. MEK inhibitors reverse resistance in epidermal growth factor receptor mutation lung cancer cells with acquired resistance to gefitinib. Mol Oncol. 2013;7:112–120. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Skehan P., Storeng R., Scudiero D., et al. New colorimetric cytotoxicity assay for anticancer-drug screening. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1990;82:1107–1112. doi: 10.1093/jnci/82.13.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang Y., Sun Y., Pan Y., et al. Frequency of driver mutations in lung adenocarcinoma from female never-smokers varies with histologic subtypes and age at diagnosis. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:1947–1953. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-2511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ding L., Getz G., Wheeler D.A., et al. Somatic mutations affect key pathways in lung adenocarcinoma. Nature. 2008;455:1069–1075. doi: 10.1038/nature07423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guibert N., Barlesi F., Descourt R., et al. Characteristics and outcomes of patients with lung cancer harboring multiple molecular alterations: results from the IFCT study biomarkers France. J Thorac Oncol. 2017;12:963–973. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2017.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Won J.K., Keam B., Koh J., et al. Concomitant ALK translocation and EGFR mutation in lung cancer: a comparison of direct sequencing and sensitive assays and the impact on responsiveness to tyrosine kinase inhibitor. Ann Oncol. 2015;26:348–354. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Piotrowska Z., Isozaki H., Lennerz J.K., et al. Landscape of acquired resistance to osimertinib in EGFR-mutant NSCLC and clinical validation of combined EGFR and RET inhibition with osimertinib and BLU-667 for acquired RET fusion. Cancer Discov. 2018;8:1529–1539. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-18-1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schmid S., Gautschi O., Rothschild S., et al. Clinical outcome of ALK-positive non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients with de novo EGFR or KRAS co-mutations receiving tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) J Thorac Oncol. 2017;12:681–688. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2016.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bayliss R., Choi J., Fennell D.A., Fry A.M., Richards M.W. Molecular mechanisms that underpin EML4-ALK driven cancers and their response to targeted drugs. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2016;73:1209–1224. doi: 10.1007/s00018-015-2117-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koivunen J.P., Mermel C., Zejnullahu K., et al. EML4-ALK fusion gene and efficacy of an ALK kinase inhibitor in lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:4275–4283. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heuckmann J.M., Balke-Want H., Malchers F., et al. Differential protein stability and ALK inhibitor sensitivity of EML4-ALK fusion variants. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:4682–4690. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-3260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Richards M.W., O’Regan L., Roth D., et al. Microtubule association of EML proteins and the EML4-ALK variant 3 oncoprotein require an N-terminal trimerization domain. Biochem J. 2015;467:529–536. doi: 10.1042/BJ20150039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spigel D.R., Edelman M.J., O’Byrne K., et al. Results from the phase III randomized trial of onartuzumab plus erlotinib versus erlotinib in previously treated stage IIIB or IV non-small-cell lung cancer: METLung. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:412–420. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.69.2160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu Y.L., Zhang L., Kim D.W., et al. Phase Ib/II study of capmatinib (INC280) plus gefitinib after failure of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibitor therapy in patients with EGFR-mutated, MET factor-dysregulated non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:3101–3109. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2018.77.7326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yu H.A., Arcila M.E., Rekhtman N., et al. Analysis of tumor specimens at the time of acquired resistance to EGFR-TKI therapy in 155 patients with EGFR-mutant lung cancers. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:2240–2247. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-2246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin C.C., Shih J.Y., Yu C.J., et al. Outcomes in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer and acquired Thr790Met mutation treated with osimertinib: a genomic study. Lancet Respir Med. 2018;6:107–116. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(17)30480-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tang Z.H., Lu J.J. Osimertinib resistance in non-small cell lung cancer: mechanisms and therapeutic strategies. Cancer Lett. 2018;420:242–246. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2018.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Christopoulos P., Endris V., Bozorgmehr F., et al. EML4-ALK fusion variant V3 is a high-risk feature conferring accelerated metastatic spread, early treatment failure and worse overall survival in ALK(+) non-small cell lung cancer. Int J Cancer. 2018;142:2589–2598. doi: 10.1002/ijc.31275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Woo C.G., Seo S., Kim S.W., et al. Differential protein stability and clinical responses of EML4-ALK fusion variants to various ALK inhibitors in advanced ALK-rearranged non-small cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol. 2017;28:791–797. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McDermott M., Eustace A.J., Busschots S., et al. In vitro development of chemotherapy and targeted therapy drug-resistant cancer cell lines: a practical guide with case studies. Front Oncol. 2014;4:40. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2014.00040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Engelman J.A., Zejnullahu K., Mitsudomi T., et al. MET amplification leads to gefitinib resistance in lung cancer by activating ERBB3 signaling. Science. 2007;316:1039–1043. doi: 10.1126/science.1141478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.