Abstract

People often speculate about what the future holds. They wonder what will happen tomorrow, and what the world will be like in the distant future. Nonetheless, people's ability to consider future possibilities may be restricted when they consider their own futures. Adults show the ‘end of history’ illusion, believing they have changed more in the past than they will in the future. Further, preschoolers are even more limited in anticipating future change, as 3-year-olds insist their current desires will persist later in life. These findings suggest a deficit in children's and adults' abilities to simulate alternative possibilities that pertain to themselves. However, we report four experiments (n = 233) suggesting otherwise, at least for children. We find that 3-year-olds accurately infer their futures when prompted to consider their past rather than present preferences. Children also succeed at inferring their past preferences when not shown items they currently prefer. This shows that children can reason about their pasts and futures, though this ability is hindered when they are shown items that anchor them to the present. Our findings suggest that children's difficulties with mental time travel reflect a failure to shift away from the present rather than an inability to simulate alternative possibilities.

This article is part of the theme issue ‘Thinking about possibilities: mechanisms, ontogeny, functions and phylogeny’.

Keywords: future thinking, mental time travel, cognitive development

1. Introduction

The future is full of uncertainty. People are motivated to prepare for future possibilities and attempts at prognostication pervade almost all areas of life. People read astrological predictions, weather reports and books about future climate change; they attempt to predict changes in the stock market, the future rate of COVID-19 transmission, and which of several job candidates is most likely to succeed. Often people's attempts to prepare for future possibilities come down to introspection about what their own futures hold. They try to anticipate whether they will later be satisfied with the choices they make today. They wonder whether their future self will regret current decisions to move to a new city, to turn down a job offer or to splurge on an expensive car.

One might expect that people would be especially adept at predicting their own futures. After all, they have a wealth of knowledge about their past and present selves. However, this is not the case: people are notoriously poor at inferring their own future states [1]. People often exhibit a presentism bias, anticipating that their future thoughts and feelings will remain largely unchanged from how they think and feel at present [2,3]. One famous example of this is the ‘end of history’ illusion: adults claim that they have changed more in the past than they will in the future, regardless of their current age [4]. Adults feel this way despite knowing what older people typically like, so they are not ignorant about the preferences of older people. Further, they often expect other adults their age will change more than them, so their difficulty does not stem from expecting people to remain the same across time [5]. Their difficulty appears to be rooted in perceptions of the self. People appear biased towards viewing their own current beliefs and preferences as especially stable and resistant to change.

A similar but more striking pattern emerges when preschoolers are asked to reason about their future selves. At present, preschoolers like things like Play-Doh and story books, and they know that adults prefer things like crossword puzzles and newspapers. However, preschoolers demonstrate an even stronger presentism bias than adults: 3-year olds expect that when they grow up, they will persist in liking Play-Doh and story books. They think this despite knowing what grown-ups usually like, and despite often reasoning correctly about what other preschoolers will like in the future [6–10].1 This shows that their failure to envision the future cannot be owing to a lack of semantic knowledge regarding the kinds of things that people usually like. With age, this strong bias subsides. By the age of 5 years, children recognize that their current preferences will change when they grow up—they correctly predict that as adults, they will prefer crossword puzzles and newspapers over Play-Doh and storybooks (e.g. [7]).

In this paper, we try to understand the source of 3-year-olds' difficulty anticipating what they will prefer as adults—as we discuss, understanding 3-year-olds' difficulties anticipating the future may tell us something about the difficulties in future thinking that persist at older ages. We first review an account holding this difficulty arises because whereas people often predict the future by attempting to simulate it, 3-year-olds struggle to do this. We then discuss an alternative account holding that their difficulties instead result because 3-year-olds are normally anchored in the present and have difficulty handling conflicts between it and the future. This account predicts that 3-year-olds will be more successful in considering their future preferences (and their past preferences as well) if conflict with the present is reduced. We test this prediction using a novel variant of the future-preference tasks. Rather than contrasting adult items against (currently preferred) child items, the version of the task reduces conflict by contrasting adult items with ones for babies.

(a) . Simulating the future

One way children and adults might try to envision their futures is by trying to simulate a world in which they feel like their future selves. This kind of simulation is often called episodic-future thinking [14] or episodic foresight [15]. People may draw on their episodic memories of past events to pre-experience future situations in an attempt to predict what the future will be like [14,16–18]. For instance, a person starting a new job in the morning might draw on their memories of past first-days at work, with small adjustments to fit their new circumstances, to imagine what their experience will be like tomorrow. Children and adults' failure to envision future change might therefore reflect a simulation failure. When they attempt to simulate their own future desires, they may fail to pre-experience a shift in their beliefs.

This account is especially plausible for children. Some work on children's reasoning about possibilities in general—how they decide what can and cannot happen—suggests that children decide whether things are possible by simulating how they might occur. Children aged 4–6 years usually deny that strange and unlikely outcomes can happen, potentially because they are unable to imagine any circumstances that would enable such events ([19,20]; for replications and extensions see [21,–23]). For example, children this age deny that a person could have a pet zebra, and they might deny this because they cannot simulate the circumstances that would enable a person to acquire one. Also, children often fail tasks that involve simulating alternative causal chains and outcomes. For instance, children younger than 12 years are especially poor reasoners when asked about overdetermined counterfactuals, in which an outcome has multiple causes and children must decide how things would be different if a single cause was removed. Children often say that the outcome will be prevented, despite there being other causes that would enable it (e.g. [24,25]; but see [26] for evidence that even 4-year-olds may sometimes succeed at such tasks). Some work has proposed that they fail here because they do not properly simulate the necessary circumstances (e.g. [25,27]).

(b) . Alternative possibilities

However, there are reasons to doubt that failures to generate simulations are the root of children's difficulties to think about possibilities, future or otherwise. For instance, although children typically deny the possibility of improbable events like owning a pet zebra, this difficulty may not stem from a failure to simulate. Instead of trying (but failing) to simulate the circumstances that would allow outcomes to occur, children may instead use a memory-based heuristic to see if they know of similar outcomes having occurred [28]. On this view, children deny the possibility of owning a pet zebra because they are unaware of similar events. Consistent with this account, children affirm the possibility of unusual outcomes if they are first informed about similar ones—for example, they affirm a person can own a pet zebra if told that someone else has a pet elephant. Importantly, this strategy does not involve simulation, since children affirm events without knowing how they could occur. Further, providing children with information about how events might occur is not sufficient to lead children to envision new possibilities [29]. So it is unlikely that simulation is the primary way in which children reason about what is possible.

The same may hold true when children reason about future possibilities, including their future preferences. That is, their inability to accurately reason about their futures might stem from difficulties other than improper simulation. Most tasks where children struggle to anticipate their future preferences confront children with pairs of items: an item they like now, and an item they should like in the future. Successfully navigating such a task (i.e. selecting the adult item) involves overcoming the conflict generated by the item they presently like. Children have to overcome the tendency to select the thing they like now (e.g. a storybook) and instead select the thing that they like less or not at all (e.g. a newspaper).

Some support for this comes from findings showing that children consistently perform better on future-preference tasks when conflict between children's present and future states is minimized or eliminated. Children are more likely to succeed and say they will prefer adult items when they are not shown an alluring child item [6], when they are allowed to first state what they like at present [30], and when they are asked to infer what they will own in the future instead of what they will like [8]. This increase in performance probably stems from a reduction in conflict, as relaying the correct answer does not involve overcoming their present desires. For example, when children are shown only adult items and asked whether they will like each in the future, they are not faced with the lure of a child object they currently prefer; and when children are shown pairs of adult and child objects and asked about future ownership, they may face less conflict because they are unlikely to own the exact child object shown (i.e. when shown a children's book, they are unlikely to own that particular book). However, these prior studies do not decisively show that children succeed when conflict is reduced. For example, children's success when shown lone items [6] could reflect a ‘yes’ bias to questions with uncertain answers [31]. Also, although asking 3-year-olds about which objects they would own in the future yielded stronger performance than asking about future preferences, their success remained relatively modest and did not exceed chance [8].

(c) . Taking stock

In summary, 3-year-olds' difficulty anticipating their future preferences might not result from problems with simulating. Instead, it may result from difficulty handling conflict between the present and future. Children may be anchored in the present and have difficulty shifting away from their current state to accurately reason about their future selves. This effect is probably exacerbated when children are directly faced with an anchor (i.e. something they currently like). On this view, inferring the future might involve something like an anchoring and adjustment heuristic [32]. Indeed, failure to shift away from a present ‘anchor’ has been suggested as an explanation for the presentism bias in adults [3]. People may use their present state as an anchor and use their semantic knowledge of what older people typically like to revise accordingly [33]. However, they may under-revise or fail to revise at all, leading to a view of their future selves as being remarkably similar to how they are at present.

Such a strategy could help explain why adults show the end of history illusion, and why preschoolers think they will be grown-ups who like Play-Doh; at all ages, people may be anchored to the present, though adults may be somewhat better at shifting towards the future than preschoolers. This strategy does not require simulation of future states, because people might succeed in anticipating the future by deploying semantic knowledge of what the future might be like. Any removal or diminishing of the anchor leads to less difficulty with shifting away from the present and therefore greater accuracy about the future.

We investigated this account across four experiments on 3-year-olds by assessing their ability to infer the future in the absence of a present anchor. We focused on children at age 3 because previous studies suggest this is when children have the most marked difficulty anticipating what they will prefer as adults (e.g. [7]). Moreover, when studies have investigated means of improving children's ability to anticipate these preferences, the improvements have been most apparent at age 3. For instance, Atance et al. [6] found that presenting items individually rather than in pairs improved performance in 3-year-olds, but not in 4- and 5-year-olds.

2. Experiment 1

In this experiment, we showed 3-year-olds pairs of items where one item is suitable for adults and the other is suitable for babies, and either asked them which they would like as grown-ups or which they had liked when they were babies. Our original aim in this experiment was testing whether children have more difficulty anticipating future preferences than those from the past. Some previous work suggests that preschoolers have difficulty acknowledging their past preferences. Specifically, one study found that 3- and 4-year-olds often decide that the things they like at present are the things they liked as a baby [9]. However, it did not compare judgements about the past with those about the future, and children were always shown a present anchor when asked about the past and future. Here, we explore these judgements in the absence of a present anchor.

(a) . Method

(i) . Participants

We tested sixty 3-year-olds (Mage = 41.7 months, 27 girls), with 30 assigned to each condition. Two additional children were tested but excluded owing to experimenter error (1) or providing no responses (1). In all experiments, except experiment 2, we aimed to test thirty 3-year-olds per between-subject condition. This stopping rule was chosen based on previous papers with similar methods, which generally included somewhat fewer children per cell (e.g. [7,8]). We sought a larger sample in experiment 2, because it had a more complicated design.

Children were recruited and individually tested at childcare centres, elementary schools and online via Zoom. Demographics were therefore not formally collected, but most children were from middle-class families in Waterloo (Ontario, Canada). Approximately 85% of residents in this region are Caucasian, and the largest visible minority groups are of Chinese and South Asian descent. All studies received approval from the Office of Research Ethics at the University of Waterloo.

(ii) . Materials and procedure

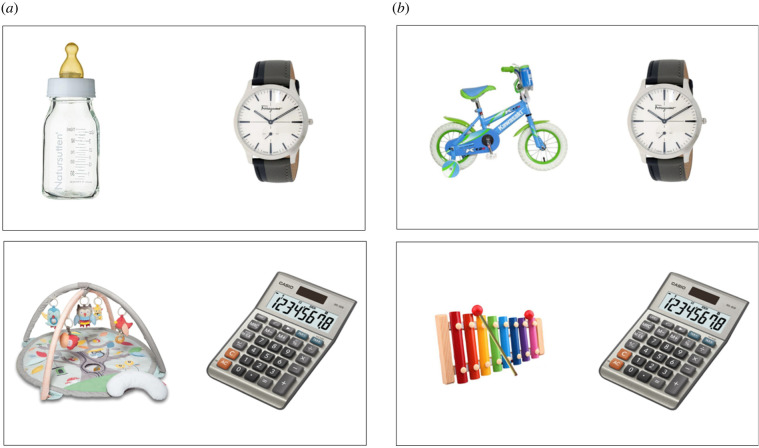

The task was administered via a PowerPoint slideshow on a laptop computer. Children were randomly assigned to infer either their past or future preferences. In the past-preference condition, children were first shown a baby and told: ‘Right now you're a kid, but before you got bigger, you were a baby just like this!’ Children in the future-preference condition saw a gender-matched adult and were told: ‘Right now you're a kid, but when you get bigger, you'll be a grown-up just like this!’ Children then saw six trials of baby and adult item pairings (e.g. a wrist-watch and a baby bottle; refer to figure 1a for sample images).

Figure 1.

Sample materials from experiments 1 and 2. (a) Shows two baby–adult item pairs from experiment 1; (b) shows corresponding child–adult item pairs from the training condition in experiment 2. Similar images were used in the other experiments. (Online version in colour.)

Children in the past-preference condition were asked to select the item they previously preferred (When you were a baby, which one did you like?). Children in the future-preference condition were asked to select the item they'd like in the future (When you grow up, which one will you like?). The items were piloted to ensure that children held a roughly equal preference for the items at present. We did this by preparing 10 baby–adult item pairings and asking thirty 3-year-olds to select the items they liked at present. Across all experiments, we used only those items for which responses here were no different from chance (i.e. 0.5), ps ≥ 0.281. Items were shown in two pseudorandom orders counterbalanced across children. The materials for all experiments can be viewed at osf.io/en37t [34].

(b) . Results and discussion

For all experiments, we coded selections of adult items as 1 and selections of baby or child items as 0. Analyses were performed using generalized estimating equations (GEE) models (binary logistic) run with ‘geepack’ for R [35]. These were passed through the ‘joint_tests’ function from the ‘emmeans’ package to produce an omnibus test; any post hoc pairwise tests were also performed using ‘emmeans’ [36]. All reported means and confidence intervals (CIs) were derived from these post hoc tests. Single-sample tests comparing children's performance to chance were performed by running separate intercept-only GEE models for each factor level. The means and CIs in each figure were derived from the main analyses and plotted using the ‘ggeffects’ package [37]. In all figures, dots show means, whiskers show 95% CIs and violins show distributions derived from each child's average score (i.e. the proportion of adult items chosen by each child). The data and R code for the analyses are available at osf.io/en37t [34].

We entered perspective (past, future) into a GEE predicting children's selection of adult items. Children more often selected adult items when asked what they would like in the future (M = 0.67, 95% CI [0.53–0.78]) than when asked what they liked in the past (M = 0.24, 95% CI [0.15–0.36]): F1 = 20.2, p < 0.001; figure 2. We then checked how often children were correct when inferring the future or past by reverse-scoring responses for the past-perspective (M = 0.76). No difference emerged: children were similarly adept at inferring both their past and future preferences: F1 = 1.31, p = 0.253; figure S1 in the OSF Supplemental Materials shows this plot [34].

Figure 2.

Proportion of adult items chosen in experiment 1. Children who inferred past preferences were asked what they liked as a baby; children who inferred future preferences were asked what they would like as an adult. (Online version in colour.)

We also checked whether children's responses differed from chance. Children mostly selected adult items when reasoning about what they will like the future: p = 0.017, and mostly selected baby items when reasoning about what they liked in the past: p < 0.001.

In summary, 3-year-olds were successful in indicating which items they had preferred as babies and which they would prefer as adults when a present anchor was absent. Because children's success did not significantly differ across these past and future judgements, these ruled out our initial expectation that children might find it easier to acknowledge their past preferences. However, the fact that 3-year-olds performed well does support the proposal that children fail to engage in mental time travel because they are anchored on items they currently prefer.

Our results also contrast somewhat with the findings of [9]. Their second experiment found that 3-year-olds respond at chance when asked to infer what they liked as babies (M = 0.49), whereas we found that 3-year-olds were mostly accurate at inferring their past preferences (M = 0.76). However, our procedure differed from theirs in many ways, and one notable difference is that their participants saw baby items paired with child-appropriate items (i.e. items that could anchor children to the present).

3. Experiment 2

The finding that 3-year-olds can succeed in anticipating future preferences when not faced with age-appropriate anchors led us to wonder if this approach can be used to improve children's performance when anchors are used. In experiment 1, children adopted a reasoning strategy that allowed them to accurately infer both their past and future preferences; for instance, they may have relied on their semantic knowledge of what babies and adults usually like. We investigated whether children's use of this successful strategy might carry-over if children were subsequently faced with things they presently prefer, leading them to reason accurately on pairings with anchors as well. Children usually fail when confronted with presently preferred items (e.g. [7,8]). So such carry-over effects would suggest that children's tendency to focus on the present is relatively malleable and can be overcome via practice considering the future. Alternatively, merely seeing a currently preferred item could anchor children in the present, leading them to persist in failing to infer future preferences despite their previous success. Experiment 2 tests between these alternatives by ‘training’ children on either baby–adult item pairs (with no anchors) or child–adult item pairs (i.e. pairs with anchors) before testing them with further child–adult trials.

The design and analysis plans for experiment 2 were preregistered at aspredicted.org and can be found at https://aspredicted.org/ty3qx.pdf.

(a) . Method

(i) . Participants

We tested eighty 3-year-olds (Mage = 41.5 months, 40 girls), with 40 assigned to each condition. Two additional children were excluded for not responding.

(ii) . Materials and procedure

The task was administered via a PowerPoint slideshow on a laptop computer. The procedure closely followed that of experiment 1, except children were always asked to infer their future preferences. Children were assigned to either the training or control condition. Children in the training condition first saw a block of three baby–adult item pairings followed by three child–adult item pairings. Children in the control condition saw six child–adult item pairings. The child–adult pairings were created by swapping out the baby items from experiment 1's item set for more age-appropriate items. For instance, the baby–adult pairing with a wrist-watch and baby bottle was changed to feature a wrist-watch and child's bicycle; we ensured that children only saw each adult item once, so these two items were assigned to different trial orders. On each trial, children were asked to select the item that they would like when they grow up. Items were shown in four pseudorandom orders, two for each condition.

(b) . Results and discussion

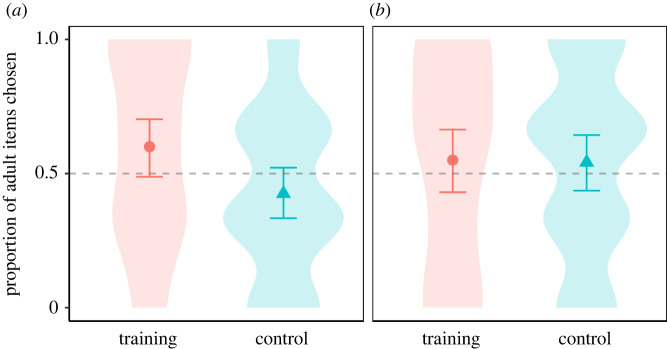

We entered condition (training, control) and block (first, last) into a GEE predicting children's selection of adult items. The effect of condition was not significant: F1 = 1.86, p = 0.173, nor was the effect of block: F1 = 0.67, p = 0.412, but there was a significant interaction between condition and block: F1 = 4.37, p = 0.037; figure 3.

Figure 3.

Proportion of adult items chosen in experiment 2. Children in the training condition saw three baby–adult item pairs in the first block (a), and three child–adult item pairs in the last block (b); children in the control condition saw only child–adult item pairs. (Online version in colour.)

In the first block, children in the training condition saw baby–adult item pairings whereas children in the control condition saw child–adult item pairings. Children said they would prefer the adult item more often when it was paired with a baby item (M = 0.60, 95% CI [0.49–0.70]) than a child item (M = 0.43, 95% CI [0.33–0.52]): p = 0.020, odds ratio = 2.03. In the last block, children in both conditions saw child–adult item pairings. We wanted to see whether children's relative success on baby–adult trials would improve their performance on the child–adult trials. However, responses in this block did not differ across conditions: p = 0.918. Also, single-sample tests showed that children's responses in each block and condition never differed from chance: ps ≥ 0.080.

In summary, our attempt to train 3-year-olds failed. Testing children using trials without the potential anchor of an age-appropriate item (i.e. trials with baby items and adult items) did not improve their subsequent performance on trials including this potential anchor. Nonetheless, the training trials reinforced the conclusion from experiment 1 that 3-year-olds may be better able to anticipate their future preferences in trials without age-appropriate items.

4. Experiment 3

Our first two experiments provide preliminary evidence that 3-year-olds more accurately infer their futures when confronted with items they preferred in the past (baby–adult trials) rather than items preferred at present (child–adult trials). This suggests that children are better able to infer their futures when they are not shown items that serve to anchor them to their present states. The final two experiments explore the robustness of this finding by further comparing children's performance on these two kinds of trials (baby–adult and child–adult). Experiment 3 employs a within-subjects design in which all children were shown both kinds of trials. Experiment 4 instead uses a between-subjects design administered in a novel format (online via Zoom). Both experiments were preregistered; these can be found at https://aspredicted.org/7au5t.pdfhttps://aspredicted.org/VY8_YSQ and https://aspredicted.org/6uq2i.pdfhttps://aspredicted.org/J26_CCV.

(a) . Method

(i) . Participants

We tested thirty-seven 3-year-olds (Mage = 41.2 months, 18 girls). All children were included in the analyses. We aimed to test 60 children but ceased data collection in March 2020 in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

(ii) . Materials and procedure

The task was administered on an Amazon Fire Tablet running the Qualtrics Offline app. Children were asked to touch the screen to make their selections. The app required that children make a single touch without sliding their finger for the response to register; children sometimes failed to do this. In these cases, the experimenter tapped the chosen item for them.

We again showed children pairings of items and asked them to select the one they would like when they grow up. Here, we manipulated the item pairings (baby–adult and child–adult) within-subjects. Children saw four baby–adult item pairings and four child–adult item pairings in a fully random order.

(b) . Results

We entered pairing (baby–adult and child–adult) and trial number (centred) into a GEE predicting children's selection of adult items. We included trial number to explore whether children's performance increased over time. The effect of pairing was not significant: F1 = 2.37, p = 0.124, nor was the effect of trial number: F1 = 0.03, p = 0.860. There was also no interaction: F1 = 0.16, p = 0.687; figure 4.

Figure 4.

Proportion of adult items chosen in experiments 3 and 4. (a) In experiment 3, all children saw baby–adult item pairs and child–adult item pairs; (b) in experiment 4, children saw either baby–adult item pairs or child–adult item pairs. Children were asked to select the item they would like when they grow up. (Online version in colour.)

Despite finding no effects, we wanted to check whether children's responses differed from chance across pairings. Children mostly chose adult items when they were paired with baby items (M = 0.64, 95% CI [0.55–0.72]): p = 0.005, but were at chance when the adult items were paired with child items (M = 0.57, 95% CI [0.48–0.66]): p = 0.151.

5. Experiment 4

(a) . Method

(i) . Participants

We tested fifty-six 3-year-olds (Mage = 42.0 months, 25 girls). We again aimed to test 60 children in total. Five additional children were excluded for either parental interference (3), technical issues (1) or declining to answer any questions (1).

(ii) . Materials and procedure

The experiment was a Qualtrics survey administered online via Zoom. The experimenter shared their screen while clicking through the survey; children were asked to indicate their answer, and the experimenter clicked the appropriate regions to enter a response.

This experiment followed a similar procedure to experiment 3, except item pairing was manipulated between-subjects. Children saw either baby–adult item pairings or child–adult items pairings. On each trial, they were asked to select the item they would like then they grow up. To accommodate the shift to an online format, each item was embedded within a coloured box that was either yellow or purple. Children completed two training trials featuring familiar animals to ensure they knew how to provide responses (e.g. ‘Which colour box is the dog in? And which colour box is the cat in?’). On test trials, children were asked: ‘Which box has the one you'll like when you grow up?’ Responses were accepted if children named an appropriate colour (e.g. ‘the yellow one’), or if they clearly stated the item they would prefer (e.g. ‘the guitar’). Children saw six item pairs in a random order.

(b) . Results and discussion

We entered pairing (baby–adult and child–adult) into a GEE predicting children's selection of adult items. The effect of pairing was not significant: F1 = 0.26, p = 0.613; figure 4. We then checked whether children's responses in each condition differed from chance. Once again, children mostly chose adult items when they were paired with baby items (M = 0.63, 95% CI [0.51–0.73]): p = 0.028, but were at chance when adult items were paired with child items (M = 0.59, 95% CI [0.50–0.68]): p = 0.061.

6. Mega-analysis

Children were mostly accurate about their future preferences when confronted with pairs of baby–adult item pairings, and at chance when confronted with child–adult item pairings. However, the findings are somewhat mixed; responses in experiment 2 never differed from chance, and experiments 3 and 4 did not reveal a main effect of item pairing. As a final check, we wanted to see if there was an overall effect of item pairing across all experiments. To this end, we combined and analysed the data from all four experiments to conduct a mega-analysis exploring how item pairing affected children's performance. This mega-analysis approach is preferable to a meta-analysis because it retains a maximal amount of information (see [38]; also [39]). We included data from the future-perspective condition of experiment 1 and all data from experiments 2, 3 and 4.

We entered pairing (baby–adult, child–adult) into a GEE predicting children's overall selection of adult items. Children more often selected adult items when shown baby–adult pairings (M = 0.64, 95% CI [0.58–0.69]) than child–adult pairings (M = 0.54, 95% CI [0.49–0.59]): F1 = 7.33, p = 0.007. We then checked whether children's responses for each pairing differed from chance. Across all experiments, children were mostly accurate about their future preferences when shown baby–adult pairings: p < 0.001, and responded at chance when shown child–adult pairings: p = 0.094.

7. General discussion

Across four experiments, we found evidence that 3-year-olds are better at inferring their futures when they are not confronted with things that anchor them to the present. In experiment 1, we found that children shown baby–adult item pairings were able to accurately infer both their past and future preferences. In experiments 2 through to 4, we showed that children are overall better at inferring their futures when faced with items they liked in the past rather than items they like at present. Importantly, experiment 2 also shows that any success at inferring the future does not allow children to subsequently overcome the anchoring effect induced by items they currently like. These findings suggest that children may fail at future thinking when the lure of their present desires prevents them from shifting to the future.

To our knowledge, only one other paper has shown success among 3-year-olds in a future-preference task: [6] found that 3-year-olds succeed when asked yes-or-no questions about their future preferences, and at higher rates than we observed. However, these findings may have been driven by a yes-bias among 3-year-olds (see [31]). Here, we show success among 3-year-olds in a future-preference paradigm that usually causes them difficulty, and the results suggest that this difficulty is largely removed when present anchors are replaced with things that were previously—but not presently—preferred.

The findings suggest that 3-year-olds' struggle to infer their futures may not be owing to a failure to simulate what they will be like. It has often been suggested that simulation is a primary way in which people reason about the future (e.g. [14,18]), and preschoolers' inaccuracies when asked about their own futures has been taken as evidence of an inability to run mental simulations (e.g. [7]). However here, children were mostly accurate about their futures when faced with a previously liked item (e.g. a baby bottle) rather than a presently liked item (e.g. a child's bicycle).

Why did the presence of an item preferred in the past facilitate children's ability to simulate the future? One possibility is that the approach of contrasting past and future preferences allows children to reason by exclusion: children might choose the adult items because they now dislike the baby items. However our pilot testing suggests this is not the case, as children liked the baby items about as much as they liked the adult items. Another possibility is that contrasting the past and future does not actually improve children's ability to anticipate their futures. Instead, removing the anchor of an age-appropriate item might only remove a source of difficulty without bringing about success—it might not bring children to actually reason about the past or future (see [40] for similar comments about manipulations claimed to improve 3-year-olds' performance on false belief tasks). But our findings again suggest this is not the case: overall, children faced with a choice between baby and adult items showed above-chance performance.

An alternative explanation is that confronting preschoolers with the choice between items desirable in the past and future helps them deploy their semantic knowledge. Previous work already showed that preschoolers are mostly accurate when asked what adults like at present, and that they are more accurate at inferring what other children will like in the future than what they themselves will like (e.g. [7,8]). This shows that preschoolers possess the semantic knowledge necessary to make successful inferences about what they will like as adults. Earlier work suggested that 3-year-olds do not use this knowledge to anticipate their own future preferences, which raised the possibility that they instead attempt to episodically simulate their futures. Our findings might show that children are better able to apply their semantic knowledge to consider their own futures when age-appropriate anchors are removed. Preschoolers may find it difficult to use semantic knowledge to infer their futures because they are anchored to the present. As we have noted, this account might also apply to adults and could help explain why they show the end of history illusion—their difficulties might not be entirely simulative.

Strictly, the explanations we have discussed are not mutually exclusive. For example, one might posit that preschoolers struggle to simulate the future precisely because they are anchored in the present (see [5] for a similar point about adults). To our knowledge, though, the evidence that children as young as the age of 3 years attempt to construct episodic simulations is very slim (for reviews see [18,41,42]). Furthermore, as reviewed in the Introduction, recent work has cast doubt on the importance of simulation for other kinds of possibility judgements that do not pertain to possibilities for the future. For example, failures to simulate how unusual events could come to occur is a promising and plausible explanation for why children aged 4–6 years usually deny that strange and unlikely outcomes can happen (e.g. [19,20]). However, these denials have been found to persist even when children are provided with causal information that should make such simulations easier to generate [29]. Moreover, children come to affirm the possibility of unusual events if provided with information about other similar unusual events [28].

Together with the current work, such findings suggest that preschoolers' conservative assessments of what is possible may not reflect failures to simulate or envision remote possibilities. Instead, their conservativism may result because they are anchored by their knowledge of the present and familiar, and because they are limited in using their factual knowledge to infer how things might otherwise be.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Venus Ho for her essential role in finishing data collection for experiment 4.

Endnote

Children also have difficulty anticipating changes on smaller timescales. For instance, after eating salty pretzels, preschoolers' thirst leads them to claim they will also want water the next day [11,12]. However, in contrast with 3-year-olds’ difficulty anticipating that they will eventually like adult items, difficulty on the ‘pretzel’ task is also found in older children and adults (e.g. [13]).

Ethics

All studies received approval from the Office of Research Ethics at the University of Waterloo.

Data accessibility

The data and materials for all experiments, as well as the R scripts used to run the analyses, are openly available on OSF at https://osf.io/en37t [34].

Authors' contributions

B.G.: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, project administration, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing; E.E.S.: data curation, investigation, project administration, resources, supervision, writing—review and editing; O.F.: conceptualization, data curation, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, project administration, supervision, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing.

All authors gave final approval for publication and agreed to be held accountable for the work performed therein.

Conflict of interest declaration

We declare we have no competing interests.

Funding

This study was funded by grants from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada awarded to B.G. and O.F.

References

- 1.Gilbert DT. 2006. Stumbling on happiness. New York: Vintage Books. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bauckham G, Lambert R, Atance CM, Davidson PS, Taler V, Renoult L. 2019. Predicting our own and others' future preferences: the role of social distance. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. (Colchester) 72, 634-642. ( 10.1177/1747021818763573) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gilbert DT, Gill MJ, Wilson TD. 2002. The future is now: temporal correction in affective forecasting. Org. Behav. Hum. Decision Process. 88, 430-444. ( 10.1006/obhd.2001.2982) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Quoidbach J, Gilbert DT, Wilson TD. 2013. The end of history illusion. Science 339, 96-98. ( 10.1126/science.1229294) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Renoult L, Kopp L, Davidson PS, Taler V, Atance CM. 2016. You'll change more than I will: adults' predictions about their own and others' future preferences. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. (Colchester) 69, 299-309. (doi:10.1080%2F17470218.2015.1046463) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Atance CM, Rutt JL, Cassidy K, Mahy CE. 2021. Young children's future-oriented reasoning for self and other: effects of conflict and perspective. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 209, 105172. ( 10.1016/j.jecp.2021.105172) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bélanger MJ, Atance CM, Varghese AL, Nguyen V, Vendetti C. 2014. What will I like best when I'm all grown up? Preschoolers' understanding of future preferences. Child Dev. 85, 2419-2431. ( 10.1111/cdev.12282) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goulding BW, Atance CM, Friedman O. 2019. An advantage for ownership over preferences in children's future thinking. Dev. Psychol. 55, 1702. ( 10.1037/dev0000759) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kopp L, Hamwi L, Atance CM. 2021. Self-projection in early development: preschoolers' reasoning about changes in their future and past preferences. J. Cogn. Dev. 22, 246-266. ( 10.1080/15248372.2021.1874954) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee WS, Atance CM. 2016. The effect of psychological distance on children's reasoning about future preferences. PLoS ONE 11, e0164382. ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0164382) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Atance CM, Meltzoff AN. 2006. Preschoolers' current desires warp their choices for the future. Psychol. Sci. 17, 583-587. ( 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01748.x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mazachowsky TR, Koktavy C, Mahy CE. 2019. The effect of psychological distance on young children's future predictions. Infant Child Dev. 28, e2133. ( 10.1002/icd.2133) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kramer HJ, Goldfarb D, Tashjian SM, Lagattuta KH. 2017. ‘These pretzels are making me thirsty’: older children and adults struggle with induced-state episodic foresight. Child Dev. 88, 1554-1562. ( 10.1111/cdev.12700) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Atance CM, O'Neill DK. 2001. Episodic future thinking. Trends Cogn. Sci. 5, 533-539. ( 10.1016/S1364-6613(00)01804-0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Suddendorf T. 2010. Episodic memory versus episodic foresight: similarities and differences. Wiley Interdisc. Rev. 1, 99-107. ( 10.1002/wcs.23) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gautam S, Suddendorf T, Henry JD, Redshaw J. 2019. A taxonomy of mental time travel and counterfactual thought: insights from cognitive development. Behav. Brain Res. 374, 112108. ( 10.1016/j.bbr.2019.112108) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schacter DL, Addis DR. 2007. The cognitive neuroscience of constructive memory: remembering the past and imagining the future. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 362, 773-786. ( 10.1098/rstb.2007.2087) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suddendorf T. 2017. The emergence of episodic foresight and its consequences. Child Dev. Perspect. 11, 191-195. ( 10.1111/cdep.12233) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shtulman A. 2009. The development of possibility judgment within and across domains. Cogn. Dev. 24, 293-309. ( 10.1016/j.cogdev.2008.12.006) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shtulman A, Carey S. 2007. Improbable or impossible? How children reason about the possibility of extraordinary events. Child Dev. 78, 1015-1032. ( 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01047.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Danovitch JH, Lane JD. 2020. Children's belief in purported events: when claims reference hearsay, books, or the internet. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 193, 104808. ( 10.1016/j.jecp.2020.104808) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lane JD, Ronfard S, Francioli SP, Harris PL. 2016. Children's imagination and belief: prone to flights of fancy or grounded in reality? Cognition 152, 127-140. ( 10.1016/j.cognition.2016.03.022) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lane JD, Ronfard S, El-Sherif D. 2018. The influence of first-hand testimony and hearsay on children's belief in the improbable. Child Dev. 89, 1133-1140. ( 10.1111/cdev.12815) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kominsky JF, Gerstenberg T, Pelz M, Sheskin M, Singmann H, Schulz L, Keil FC. 2021. The trajectory of counterfactual simulation in development. Dev. Psychol. 57, 253. ( 10.1037/dev0001140) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rafetseder E, Schwitalla M, Perner J. 2013. Counterfactual reasoning: from childhood to adulthood. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 114, 389-404. ( 10.1016/j.jecp.2012.10.010) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nyhout A, Ganea PA. 2019. Mature counterfactual reasoning in 4-and 5-year-olds. Cognition 183, 57-66. ( 10.1016/j.cognition.2018.10.027) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leahy B, Rafetseder E, Perner J. 2014. Basic conditional reasoning: how children mimic counterfactual reasoning. Studia Logica 102, 793-810. ( 10.1007/s11225-013-9510-7) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goulding BW, Friedman O. 2021. A similarity heuristic in children's possibility judgments. Child Dev. 92, 662-671. ( 10.1111/cdev.13534) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goulding BW, Stonehouse EE, Friedman O. 2022. Causal knowledge and children's possibility judgments. Child Dev. 93, 794-803. ( 10.1111/cdev.13718) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Atance CM, Bélanger M, Meltzoff AN. 2010. Preschoolers' understanding of others’ desires: fulfilling mine enhances my understanding of yours. Dev. Psychol. 46, 1505. ( 10.1037/a0020374) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fritzley VH, Lee K. 2003. Do young children always say yes to yes–no questions? A metadevelopmental study of the affirmation bias. Child Dev. 74, 1297-1313. ( 10.1111/1467-8624.00608) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tversky A, Kahneman D. 1974. Judgment under uncertainty: heuristics and biases. Science 185, 1124-1131. ( 10.1126/science.185.4157.1124) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Birch SA, Bernstein DM. 2007. What can children tell us about hindsight bias: a fundamental constraint on perspective–taking? Soc. Cogn. 25, 98-113. ( 10.1521/soco.2007.25.1.98) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goulding BW, Stonehouse EE, Friedman O. 2022. Anchored in the present: preschoolers more accurately infer their futures when confronted with their pasts. OSF. See https://osf.io/en37t.

- 35.Højsgaard S, Halekoh U, Yan J. 2006. The R package geepack for generalized estimating equations. J. Stat. Softw. 15, 1-11. ( 10.18637/jss.v015.i02) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lenth R. 2019. emmeans: Estimated Marginal Means, aka Least-Squares Means. Retrieved from https://cran.r-project.org/package=emmeans. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lüdecke D. 2018. ggeffects: tidy data frames of marginal effects from regression models. J. Open Sour. Softw. 3, 772. ( 10.21105/joss.00772) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eisenhauer JG. 2021. Meta-analysis and mega-analysis: a simple introduction. Teaching Stat. 43, 21-27. ( 10.1111/test.12242) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Koile E, Cristia A. 2021. Toward cumulative cognitive science: a comparison of meta-analysis, mega-analysis, and hybrid approaches. Open Mind 5, 154-173. ( 10.1162/opmi_a_00048) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wellman HM, Cross D, Watson J. 2001. Meta-analysis of theory-of-mind development: the truth about false belief. Child Dev. 72, 655-684. ( 10.1111/1467-8624.00304) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Atance CM. 2015. Young children's thinking about the future. Child Dev. Perspect. 9, 178-182. ( 10.1111/cdep.12128) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hudson JA, Mayhew EM, Prabhakar J. 2011. The development of episodic foresight: emerging concepts and methods. Adv. Child Dev. Behav. 40, 95-137. ( 10.1016/B978-0-12-386491-8.00003-7) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data and materials for all experiments, as well as the R scripts used to run the analyses, are openly available on OSF at https://osf.io/en37t [34].