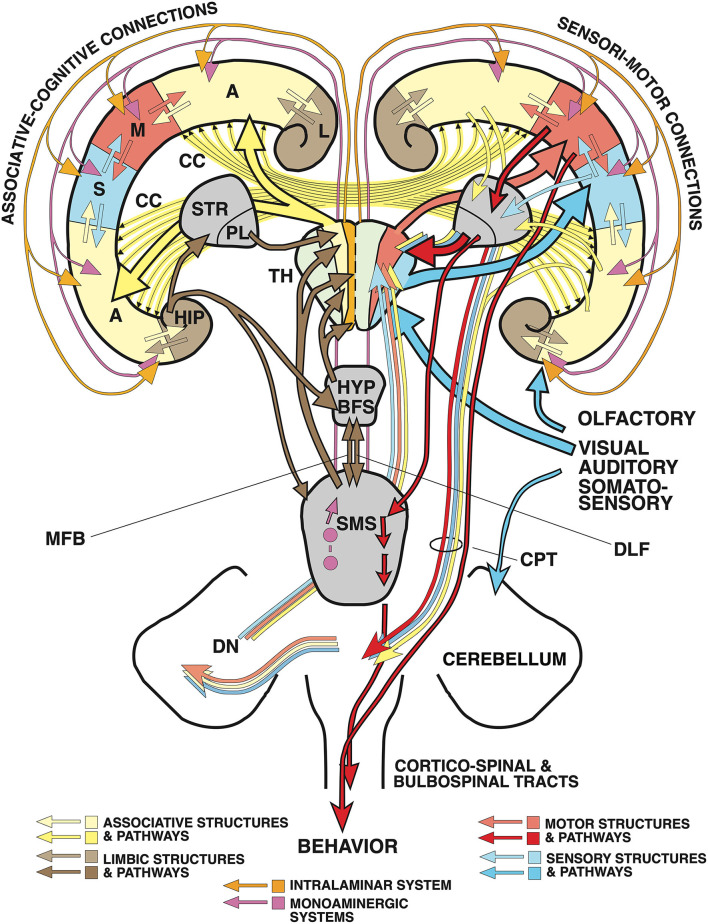

Figure 2.

“Cognitive” and “non-cognitive” circuitry of the mammalian brain. At right, the main connections of the primary sensory (S) and motor cortex areas (M) are described in further detail in the text, see also Lipp and Wolfer (1998). The left side illustrates the connectivity of the “cognitive” (associative and limbic) cortex. Principal inputs to association cortex (A) originate in the hypothalamus (HYP) and the reticular formation (RF) and reaches the non-specific (associational) thalamus (TH, yellow) from where ascending divergent fibers reach many parts of the associative cortex (A). The connections of the associative cortex include reciprocal fiber connections with neighboring areas subserving tangential spread of information. Part of the output of the association cortex is fed into the motor fine-tuning loops, to the other hemisphere via the corpus callosum (CC), and via polysynaptic chains into the (marginal) limbic cortex (L) and the hippocampal formation (HIP). The cingular and entorhinal cortex send also fibers to the limbic basal ganglia (STR) where the limbic pallidum (PL) sends (probably inhibitory) fibers to the intralaminar system of the thalamus and to the anterior thalamic nuclei. Other fibers from hippocampus and amygdala reach the hypothalamus and reticular formation, both structures sending fibers to the associative thalamus from which divergent axons spread again to the associative cortex portions. Thus, the activity of the entire cortex can be structured through ascending control systems: the intralaminar system (orange), and the ascending monoaminergic systems (purple), see also text. Any alteration in these comparatively minor structures, be it genetic, developmental, or pathological, has thus a potentially powerful impact. An earlier version of this figure has been published by Lipp and Wolfer (1998), the actual one is modified and has been re-labeled by H.P.L.