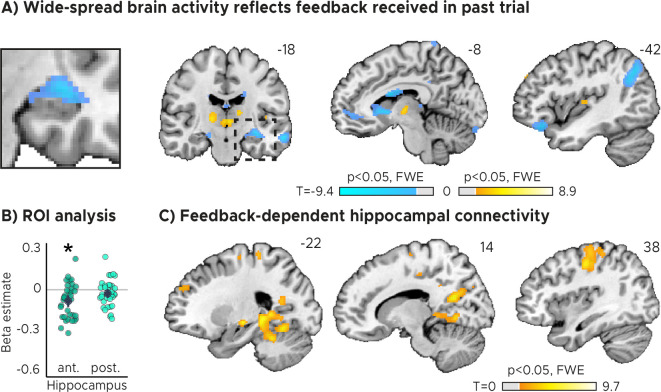

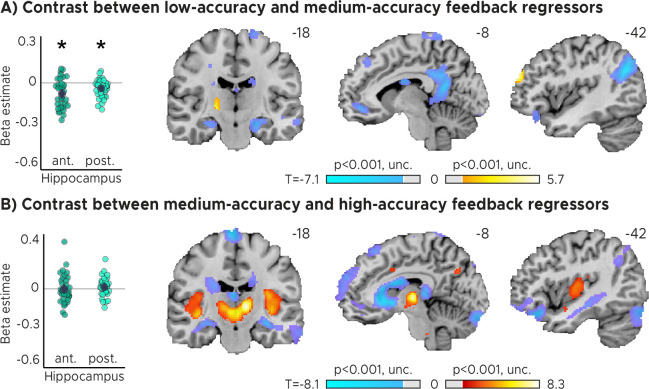

Figure 2. Feedback on the previous trial (n-1) modulates network-wide activity and hippocampal connectivity in subsequent trials (n).

(A) Voxel-wise analysis. Activity in each trial was modeled with a separate regressor as a function of feedback received in the previous trial. Insert zooming in on hippocampus added. (B) Independent regions-of-interest analysis for the anterior (ant.) and posterior (post.) hippocampus. We plot the beta estimates obtained for the contrast between low-accuracy vs. high-accuracy feedback. Negative values indicate that smaller errors, and higher-accuracy feedback, led to stronger activity. Depicted are the mean and SEM across participants (black dot and line) overlaid on single participant data (coloured dots; n=34). Activity in the anterior hippocampus is modulated by feedback received in previous trial. Statistics reflect p<0.05 at Bonferroni-corrected levels (*) obtained using a group-level two-tailed one-sample t-test against zero. (C) Feedback-dependent hippocampal connectivity. We plot results of a psychophysiological interactions (PPI) analysis conducted using the hippocampal peak effects in (A) as a seed for low vs. high-accuracy feedback. (AC) We plot thresholded t-test results at 1 mm resolution overlaid on a structural template brain. MNI coordinates added. Hippocampal activity and connectivity is modulated by feedback received in the previous trial.

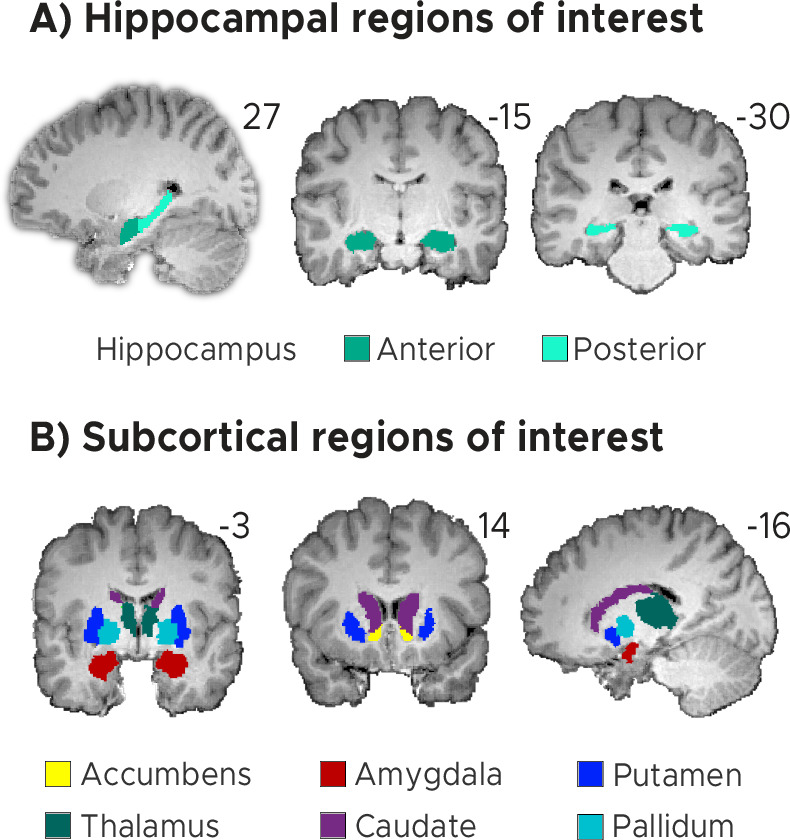

Figure 2—figure supplement 1. Regions of interest (ROIs).