Abstract

The chloramination of bromide containing waters results in the formation of bromine containing haloamines: monobromamine (NH2Br), dibromamine (NHBr2), and bromochloramine (NHBrCl). Many studies have directly shown that bromamines are more reactive than chloramines in oxidation and substitution reactions with organic water constituents because the bromine atom in oxidants is more labile than the chlorine atom. However, similar studies have not been performed with NHBrCl. It has been assumed that NHBrCl has similar reactivity as bromamines with organic constituents in both oxidation and substitution reactions because NHBrCl, like bromamines, rapidly oxidizes N,N-diethyl-p-phenylenediamine. In this study, we examined the reactivity of NHBrCl with phenol red to determine if NHBrCl reacts as readily as bromamines in an isolated substitution reaction. NHBrCl was synthesized two ways to assess whether NHBrCl or the highly reactive intermediates, bromine chloride (BrCl) and molecular bromine (Br2), were responsible for bromine substitution of phenol red. NHBrCl was found to be much less reactive than bromamines with phenol red and that BrCl and Br2 appeared to be the true brominating agents in solutions where NHBrCl is formed. This work highlights the need to reexamine what the true brominating agents are in chloraminated waters containing bromide.

Introduction

Accurate kinetic models for the chloramination of bromide ion (Br−) containing waters are valuable because the mixture of haloamines formed have varying rates of decay and reactivity with organic water constituents like natural organic matter (NOM) (Pope and Speitel 2008). The brominated haloamines that form at drinking water treatment conditions [pH 7–8.5, 3–5 Cl2 = N mass ratio, [Br−] = 0.1–2 mg Br−/L, (total chlorine) = 0.5–4 mg Cl2/L] are monobromamine (NH2Br), dibromamine (NHBr2), and bromochloramine (NHBrCl) (American Water Works Association 2018; Amy and AWWA Research Foundation, Metropolitan Water District of Southern California 1994). The reactivities of free bromine and bromamines with NOM surrogates via electrophilic aromatic substitution (bromination) and electron transfer (oxidation) reactions have been directly studied and have rate constants that are 101 to 105 times greater than those of their chlorinated counterparts (Heeb et al. 2014, 2017). Therefore, more disinfection byproducts (DBPs) are formed from reactions with brominated oxidants, and specifically, brominated DBPs are formed which are more toxic and contribute more to regulatory limits than chlorinated DBPs (Yang et al. 2014).

NHBrCl is particularly important because under many conditions it is the most abundant and persistent brominated haloamine that forms (Allard et al. 2018a). Hu et al. (2021) used membrane introduction mass spectrometry to show that NHBrCl concentration in raw water with a high Br− concentration (~1 mg/LBr−) dosed with NH2Cl can get as high as 1.8 μM. Generally, NHBrCl is formed in most studies via one of two methods: (1) combining NH2Cl with free bromine (HOBr Method); or (2) combining NH2Cl with an excess of Br− (Br− Method) (Gazda et al. 1993; Trofe et al. 1980). The formation of NHBrCl by combining NH2Cl and hypobromous acid (HOBr) is fast and occurs via a single step mechanism [Eq. (1)] where the bromine in HOBr is directly substituted and replaces a proton in NH2Cl (Gazda and Margerum 1994)

| (1) |

The reaction mechanism for the NH2Cl and Br− reaction is slower as characterized by Gazda (1994) who showed that it is a three-step mechanism [Eqs. (2)–(4)] where Br− is oxidized [Eq. (2)], forms two highly reactive free bromine intermediates [bromine chloride (BrCl) and molecular bromine (Br2)] that maintain equilibrium [Eq. (3)]. Br2 ultimately reacts with NH2Cl to form NHBrCl [Eq. (4)]

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

Work by Valentine (1986) showed that of the two halogens in NHBrCl only the bromine rapidly oxidized N,N-Diethyl-p-phenylenediamine (DPD). Valentine postulated that in reactions between NHBrCl and organics, the bromine component would behave similarly to the more reactive bromamines; these reactions have been incorporated into chloramination kinetic models (Alsulaili 2009; Zhai et al. 2014; Zhu and Zhang 2016). Recent studies, however, have shown BrCl and Br2 to be 103 to 108 times more reactive brominating agents than HOBr (Broadwater et al. 2018; Sivey et al. 2013). Therefore, the difference in reactivity of BrCl and Br2 relative to NHBrCl would be even greater than that of HOBr, and BrCl and Br2 could be responsible for brominating organics in solutions where NHBrCl is believed to be the active brominating agent.

The goal of this study was to assess if the bromine component of NHBrCl reacts as readily as the bromine components of NH2Br and NHBr2 in a specific electrophilic substitution reaction. The results of the study imply that BrCl and Br2 are the brominating agents that must be accounted for in kinetic models and analysis of data involving chloramination of Br− containing waters.

Materials and Methods

Preparation of Chlorine, Bromide, Ammonia, and Bromine Dosing Solutions

Reagent grade chemicals and ultrapure water (18.2 MΩ · cm, Milli-Q, Millipore) were used to prepare all solutions in this work. A 4.99% sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl) solution was used for making NH2Cl and hypobromite ion (OBr−) solutions. The concentration of hypochlorite ion (OCl−) was determined before use by measuring the absorbance on an Agilent 8454 UV-Vis spectrophotometer at 292 nm, using a molar absorptivity of 362 M−1 cm−1 (Furman and Margerum 1998). The stock Br− solution was prepared by dissolving potassium bromide. The ammonia solution was prepared by dissolving ammonium chloride. The stock OBr− solution was prepared by combining NaOCl with Br− at a Br−/Cl2 molar ratio of 1.05. The exact concentration of the OBr− solution was determined by monitoring the absorbance for OBr− at 329 nm and using a molar absorptivity of 332 M−1 cm−1 (Troy and Margerum 1991). All solutions were stored at 4 °C before use.

NH2Cl Synthesis

A NH2Cl solution was prepared by adding NaOCl dropwise to ammonia at a chlorine to ammonia-nitrogen (Cl2/N) mass ratio of three. The ammonia solution was adjusted to a pH of 9 before mixing. The NH2Cl solution was made fresh before preparing NHBrCl solutions. The concentration of the NH2Cl solution was determined by measuring the absorbance at 243 nm, using a molar absorptivity of 461 M−1 cm−1 (Kumar et al. 1986).

NHBrCl Synthesis

NHBrCl solutions were formed two ways in this work. The first NHBrCl synthesis method (HOBr Method) was performed by combining equal volumes of NH2Cl and HOBr solutions in 10 mM acetate buffer at pH 5 to achieve final concentrations of 3 mg Br2/L HOBr and 3.2 mg Cl2/L NH2Cl (HOBr/NH2Cl molar ratio of 0.42). The second synthesis method (Br− Method) combined equal volumes of NH2Cl and Br− solutions in 10 mM acetate buffer at pH 5 to achieve a final concentration of approximately 4.5 mg Cl2/L NH2Cl with a Br−/NH2Cl molar ratio of one (5.07 mg Br−/L). Under the Br− Method conditions, the Gazda mechanism described by Eqs. (2)–(4) will form BrCl and Br2 prior to forming NHBrCl. Both methods had total oxidant concentrations of approximately 4.5 mgCl2/L, and the pH of the NH2Cl solution was decreased to a pH of 5 immediately before use to limit dichloramine (NHCl2) formation.

Phenol Red Method for Examining Bromine Substitution of Organics by Combined Bromamines

In this work, phenol red was used to assess the efficacy of NHBrCl as a brominating agent. Phenol red is not generally used as a NOM surrogate, but it has two phenol groups (common characteristic of NOM surrogates) (Guo and Lin 2009), which both undergo electrophilic aromatic substitution by free bromine and bromamines to form bromophenol red. At a pH range of 4.8 to 5, the conversion of phenol red to bromophenol red results in a color change from yellow to violet that can be quantified by monitoring the absorbance at 588 nm. Sollo et al. (1971) developed this method to measure total bromine concentrations (free and combined) by mixing 50 mL of sample, 5 mL of 1.8 M acetate buffer at pH 5, and 2 mL of 0.01% phenol red solution. The reaction of the bromine component of oxidants with phenol red can be thought of as the extent of bromination of an organic constituent that is quantified to determine total bromine. Sollo et al. (1971) showed in experiments, which we reproduced to validate the methodology, that the absorbance at 588 nm for the bromination of phenol red to bromophenol red is linear between 1 and 5 mg Br2/L, and all inorganic bromamines at a concentration of 3 mg Br2/L completely brominate the phenol red in less than 5 min (Figs. S1 and S2). The phenol red method predates the identification of NHBrCl as a brominated haloamine, and this work is intended to determine if NHBrCl reacts with phenol red at a comparable rate relative to bromamines. If NHBrCl is less reactive than bromamines, then existing kinetic models and studies of chloraminated waters with Br− will need to be reexamined to correct the existing assumptions about NHBrCl reactivity.

NHBrCl Reactivity Experiments

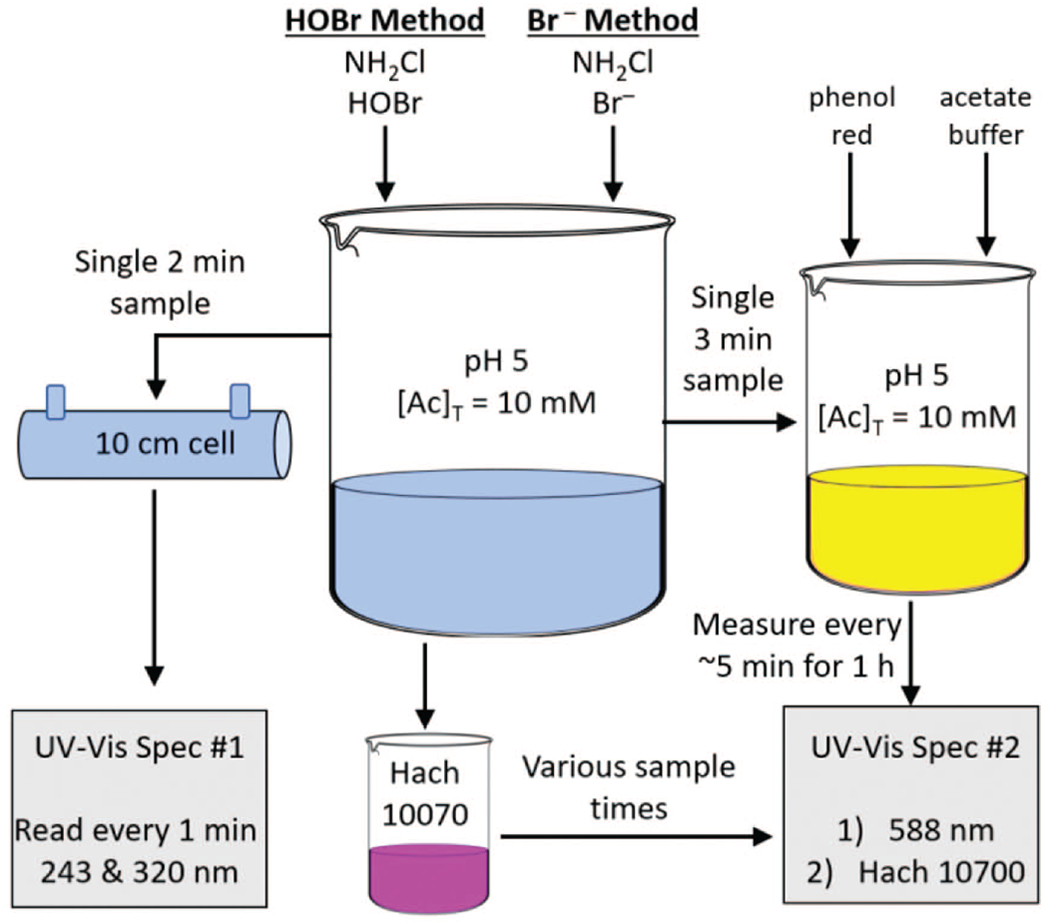

Two kinetic experiments were initiated by performing each of the two NHBrCl synthesis methods in batch reactors (Fig. 1). Two minutes after starting the experiment, a sample from each kinetic experiment batch reactor was loaded into a 10 cm quartz cell and absorbance measurements were taken every minute at 243 nm and 320 nm for 1 hour, and the molar absorptivities for both NH2Cl (ε243 = 461 and ε320 = 7 M−1 cm−1) and NHBrCl (ε243 = 745 and ε320 = 304 M−1 cm−1) were used to determine NH2Cl and NHBrCl temporal concentrations (Allard et al. 2018b; Gazda 1994; Hand and Margerum 1983; Luh and Mariñas 2014; Huwaldt and Steinhorst 2020). Three minutes after starting the experiment, a 50 mL sample was taken from each experimental batch reactor and treated with phenol red, creating a solution to allow temporal measurements of the extent of bromination for 1 h. The phenol red solution used for determining the extent of bromination and the UV-Vis method for measuring NH2Cl and NHBrCl concentrations were conducted concurrently, using two spectrophotometers. The total oxidant concentration was also measured periodically using the Hach Method 10070 (Hach Company 2018) by sampling each kinetic experiment batch reactor to validate the NH2Cl and NHBrCl concentrations determined with UV-Vis absorbance measurements.

Fig. 1.

Schematic of the kinetic experiment batch reactor and sampling regimen.

Results and Discussion

Measurement and Formation of Stable NHBrCl

The total oxidant concentrations measured using the UV-Vis method and Hach Method 10070 are in good agreement over the course of the two experiments using different NHBrCl formation methods [Figs. 2(a and b)]. Hach Method 10070 is a DPD oxidation method that is catalyzed by iodide that measures the total oxidant concentrations for chloramines, bromamines, and NHBrCl (dihaloamines have two equivalents of oxidant). The UV-Vis method assumes that the only major species that are present in solution are NH2Cl and NHBrCl, and that the sum of these two species is the total oxidant concentration. The difference between the total oxidant concentrations measured using the UV-Vis method and Hach Method 10070 ranged from −7.7% to −13.8% for the HOBr Method and −4.6% to −12.4% for the Br− Method. The small differences validated that the UV-Vis method accurately measured NHBrCl over the course of the experiments and that a low concentration of NHCl2 was formed over the course of each experiment, causing minimal interference with the results.

Fig. 2.

Experimental data for the effects of bromochloramine (NHBrCl) synthesis: (a) HOBr Method ([NH2Cl]0 = 3.2 mg Cl2/L, [HOBr]0 = 3 mgBr2/L); and (b) Br− Method ([NH2Cl]0 = 4.5mgCl2/L, [Br−]0 = 5.07 mg Br−/L) on the bromination of phenol red at pH = 5 with 10 mM acetate buffer.

The two methods of NHBrCl synthesis resulted in the formation of relatively stable solutions of NHBrCl over the course of the experiments. The HOBr Method [Eq. (1)] resulted in rapid formation of NHBrCl via direct bromine substitution and reached the desired total bromine concentration of approximately 2.9 mg Br2/L for the duration of the whole experiment [Fig. 2(a)]. The Br™ Method [Eqs. (2)–(4)] results in the continuous generation of NHBrCl that slowed down as Br™ and NH2Cl were consumed and took approximately 35 min to reach 3 mg Br2/L. Both experiments displayed a steady decay of total oxidant, due to the autodecomposition of haloamines at pH 5 (Luh and Mariñas 2014), over the duration of the experiments; total oxidant loss was 8.7% for the HOBr Method and 4.3% for the Br™ Method.

Reactivity of NHBrCl with Phenol Red

No significant bromination of phenol red occurred over the entire 1-hour experiment for the HOBr Method, suggesting that the bromine in NHBrCl is not as reactive as the bromine in bromamines. In the HOBr Method, a small increase in absorbance was observed for the phenol red method aliquot but could not be quantified because it was below the absorbance corresponding to 1 mg Br2/L and therefore out of the linear range of the standard curve (Fig. S3). For this reason, total bromine measured using the phenol red method was excluded from Fig. 2(a). Sollo et al. (1971) showed that 3 mg Br2/L solutions of bromamines completely reacted with phenol red in less than 5 min, while the NHBrCl in the HOBr Method barely reacted with phenol red in an hour. If NHBrCl rapidly reacted with phenol red, the NHBrCl concentration measured via the UV-Vis method on a total bromine basis would be close to the total bromine concentration determined by the phenol red method. The small increase in absorbance corresponding to bromination of phenol red could be due to BrCl and/or Br2 that formed by NH2Cl reacting with excess Br™ or HOBr from the decay of NHBrCl instead of NHBrCl itself (Luh and Mariñas 2014; Valentine 1982). These results indicate that NHBrCl reacts with phenol red at a much slower rate than bromamines, which challenges the common assumption that the bromine in bromamines and NHBrCl have similar reactivities.

In the Br™ Method [Fig. 2(b)], NHBrCl slowly formed over the course of the entire experiment because the reaction in Eq. (2) is much slower than the reaction in Eq. (1). The absorbance in the phenol red treated sample steadily increased over the entire experiment (Fig. S3). At 25 min, the extent of bromination of phenol red in the Br™ method could be quantified and corresponded to a concentration of 1 mg Br2/L which continued to steadily increase over the remainder of the experiment. The bromination of phenol red in the BrȒ Method but not the HOBr Method supports our hypothesis that BrCl and/or Br2 are the true brominating agents. The difference in the NHBrCl concentration on a total bromine basis for the UV-Vis method and extent of bromination of phenol red is due to a combination of the dilution involved with the phenol red method and the competition between BrCl and Br2 reacting with phenol red or reacting with NH2Cl to form NHBrCl.

Conclusions

The bromine in the mixed haloamine, NHBrCl, has been shown to be less reactive than bromamines with phenol red. In waters with NH2Cl and Br™, the reactive intermediates that form (BrCl and Br2) were responsible for bromination that is generally attributed to NHBrCl. Further research is needed to test whether the bromine in NHBrCl is less reactive than bromamines with other NOM surrogates, NOM, and organics present in waters disinfected with chloramines. In such work, researchers will need to be conscious of the method used to form NHBrCl to minimize the reaction between NH2Cl and Br™ that generates BrCl and Br2. The best approach for forming NHBrCl may be to combine NH2Cl and HOBr at pH values lower than traditionally seen in drinking waters (to ensure excess total ammonia is present as ammonium which is unreactive with HOBr) and then subsequently raise the pH to more appropriate values for drinking water (Wajon and Morris 1982). Such an approach would allow for more direct examination of NHBrCl on DBP formation by limiting Br™ oxidation and formation of reactive intermediates.

If the trends observed with phenol red are consistent with other organic water constituents, the difference in the generation of Br2 and BrCl in chloraminated and chlorinated systems could potentially explain the difference in distribution of DBPs that form for the two types of disinfectants. In systems with preformed chloramines (chloramines are both the primary and secondary disinfectant), low concentrations of BrCl and Br2 will continuously be generated as treated water moves through distribution systems (hours and days) due to the slow reaction between NH2Cl and Br− at typical pH values for drinking water (Gazda 1994; Luh and Mariñas 2014). In chlorinated systems, Br− is oxidized to the intermediates BrCl and Br2 before forming HOBr/OBr™ which is complete within the first several minutes that free chlorine is applied in a treatment plant (Brodfuehrer et al. 2020; Kumar and Margerum 1987). Chloraminated waters form lower concentrations of regulated DBPs like trihalomethanes and haloacetic acids but a broader distribution of unregulated DBPs like haloacetonitriles and N-nitrosodimethylamine than chlorinated waters (Diehl et al. 2000; Hua and Reckhow 2007; Kristiana et al. 2009; Luh and Mariñas 2012; Zhai et al. 2014). The difference in the rates at which Br™ is oxidized and BrCl and Br2 are generated in chloraminated and chlorinated systems could result in different reaction pathways involving BrCl and Br2 being favored and explain the different distribution of DBPs that form based on the disinfectant used. Additional work will be necessary to test this hypothesis, but the findings in this work regarding NHBrCl reactivity and potential importance of BrCl and Br2 in chloraminated waters emphasize the importance in identifying the active brominating species that could lead to a better understanding of DBP formation mechanisms.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant 1953206.

Footnotes

Disclaimer

The research presented was not performed or funded by EPA and was not subject to EPA’s quality system requirements. The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views or the policies of the US Environmental Protection Agency. Any mention of trade names, manufacturers, or products does not imply an endorsement by the United States Government or the US Environmental Protection Agency. The EPA and its employees do not endorse any commercial products, services, or enterprises.

Supplemental Materials

Figs. S1–S3 are available online in the ASCE Library (www.ascelibrary.org).

Data Availability Statement

All data, models, and code generated or used during the study appear in the published article.

References

- Allard S, Cadee K, Tung R, and Croué JP. 2018a. “Impact of brominated amines on monochloramine stability during in-line and pre-formed chloramination assessed by kinetic modelling.” Sci. Total Environ 618 (Mar): 1431–1439. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.09.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allard S, Hu W, Le Menn JB, Cadee K, Gallard H, and Croué JP. 2018b. “Method development for quantification of bromochloramine using membrane introduction mass spectrometry.” Environ. Sci. Technol 52 (14): 7805–7812. 10.1021/acs.est.8b00889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alsulaili A 2009. Impact of bromide, NOM, and prechlorination on haloamine formation, speciation, and decay during chloramination. Austin, TX: Univ. of Texas at Austin. [Google Scholar]

- American Water Works Association. 2018. 2017 water utility disinfection survey report. Denver: American Water Works Association. [Google Scholar]

- Amy G, and AWWA Research Foundation, Metropolitan Water District of Southern California. 1994. Survey of bromide in drinking water and impacts on DBP formation. Denver: American Water Works Research Foundation Report. [Google Scholar]

- Broadwater MA, Swanson TL, and Sivey JD. 2018. “Emerging investigators series: Comparing the inherent reactivity of often-overlooked aqueous chlorinating and brominating agents toward salicylic acid.” Environ. Sci. Water Res. Technol 4 (3): 369–384. 10.1039/C7EW00491E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brodfuehrer SH, Wahman DG, Alsulaili A, Speitel GE Jr., and Katz LE. 2020. “Role of carbonate species on general acid catalysis of bromide oxidation by hypochlorous acid (HOCl) and oxidation by molecular chlorine (Cl2).” Environ. Sci. Technol 54 (24): 16186–16194. 10.1021/acs.est.0c04563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diehl AC, Speitel GE Jr., Symons JM, Krasner SW, Hwang CJ, and Barrett SE. 2000. “DBP Formation during chloramination.” Am. Water Works Assoc 92 (6): 76–90. 10.1002/j.1551-8833.2000.tb08961.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Furman CS, and Margerum DW. 1998. “Mechanism of chlorine dioxide and chlorate ion formation from the reaction of hypobromous acid and chlorite ion.” Inorg. Chem 37 (17): 4321–4327. 10.1021/ic980262q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazda M 1994. “Non-metal redox reactions of chloramines with bromide ion and with bromine and the development and testing of a mixing cell for a new pulsed-accelerated-flow spectrophotometer with position-resolved observation.” Ph.D. dissertation, Dept. of Chemistry, Purdue Univ. [Google Scholar]

- Gazda M, Dejarme LE, Choudhury TK, Cooks RG, and Margerum DW. 1993. “Mass spectrometric evidence for the formation of bromochloramine and N-Bromo-N-chloromethylamine in aqueous solution.” Environ. Sci. Technol 27 (3): 557–561. 10.1021/es00040a015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gazda M, and Margerum DW. 1994. “Reactions of monochloramine with Br2, Br3−, HOBr, OBr−: Formation of bromochloramines.” Inorg. Chem 33 (1): 118–123. 10.1021/ic00079a022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guo G, and Lin F. 2009. “The bromination kinetics of phenolic compounds in aqueous solution.” J. Hazard. Mater 170 (2–3): 645–651. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2009.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hach Company. 2018. Method 10070, chlorine, free and total, high range. USEPA DPD Method, 0.1 to 10 mg Cl2/L. Loveland, CO: Hach Company. [Google Scholar]

- Hand VC, and Margerum DW. 1983. “Kinetics and mechanisms of the decomposition of dichloramine in aqueous solution.” Inorg. Chem 22 (10): 1449–1456. 10.1021/ic00152a007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heeb MB, Criquet J, Zimmermann-Steffens SG, and von Gunten U. 2014. “Oxidative treatment of bromide-containing waters: Formation of bromine and its reactions with inorganic and organic compounds—A critical review.” Water Res. 48 (Oct): 15–42. 10.1016/j.watres.2013.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heeb MB, Kristiana I, Trogolo D, Arey JS, and Von Gunten U. 2017. “Formation and reactivity of inorganic and organic chloramines and bromamines during oxidative water treatment.” Water Res. 110 (Mar): 91–101. 10.1016/j.watres.2016.11.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu W, Lauritsen FR, and Allard S. 2021. “Identification and quantification of chloramines, bromamines and bromochloramine by membrane introduction mass spectrometry (MIMS).” Sci. Total Environ 751 (Jan): 142303. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.142303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua G, and Reckhow DA. 2007. “Comparison of disinfection byproduct formation from chlorine and alternative disinfectants.” Water Res. 41 (8): 1667–1678. 10.1016/j.watres.2007.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huwaldt JA, and Steinhorst S. 2020. “Plot digitizer 3.1.4. PlotDigitizer-software.” Accessed May 20, 2022. https://plotdigitizer.com.

- Kristiana I, Gallard H, Joll C, and Croué JP. 2009. “The formation of halogen-specific TOX from chlorination and chloramination of natural organic matter isolates.” Water Res. 43 (17): 4177–4186. 10.1016/j.watres.2009.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar K, Day RA, and Margerum DW. 1986. “Atom-transfer Redox kinetics: General-acid-assisted oxidation of iodide by chloramines and hypochlorite.” Inorg. Chem 25 (24): 4344–4350. 10.1021/ic00244a012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar K, and Margerum DW. 1987. “Kinetics and mechanism of general-acid-assisted oxidation of bromide by hypochlorite and hypochlorous acid.” Inorg. Chem 26 (16): 2706–2711. 10.1021/ic00263a030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Luh J, and Mariñas BJ. 2012. “Bromide ion effect on N -Nitrosodimethylamine formation by monochloramine.” Environ. Sci. Technol 46 (9): 5085–5092. 10.1021/es300077x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luh J, and Mariñas BJ. 2014. “Kinetics of bromochloramine formation and decomposition.” Environ. Sci. Technol 48 (5): 2843–2852. 10.1021/es4036754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope PG, and Speitel GE. 2008. “Reactivity of bromine-substituted haloamines in forming haloacetic acids.” Disinfection by-products in drinking water: Occurrence, formation, health effects, and control. ACS symp. ser 995, 182–197. Washington, DC: American Chemical Society. [Google Scholar]

- Sivey JD, Samuel Arey J, Tentscher PR, and Lynn Roberts A. 2013. “Reactivity of BrCl, Br2, BrOCl, Br2O and HOBr toward dimethenamid in solutions of bromide + aqueous free chlorine.” Environ. Sci. Technol 47 (15): 8990. 10.1021/es302730h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sollo FW, Larson TE, and McGurk FF. 1971. “Colorimetric methods for bromine.” Environ. Sci. Technol 5 (3): 240–246. 10.1021/es60050a009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Trofe TW, Inman GW, and Donald Johnson J. 1980. “Kinetics of monochloramine decomposition in the presence of bromide.” Environ. Sci. Technol 14 (5): 544–549. 10.1021/es60165a008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Troy RC, and Margerum DW. 1991. “Non-metal Redox kinetics: Hypobromite and hypobromous acid reactions with iodide and with sulfite and the hydrolysis of bromosulfate.” Inorg. Chem 30 (18): 3538–3543. 10.1021/ic00018a028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Valentine RL 1982. “The disappearance of chloramines in the presence of bromide and nitrite.” Ph.D. dissertation, Dept. of Civil Engineering, Univ. of California. [Google Scholar]

- Valentine RL 1986. “Bromochloramine oxidation of N,N-diethyl-p-phenylenediamine in the presence of monochloramine.” Environ. Sci. Technol 20 (2): 166–170. 10.1021/es00144a009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wajon JE, and Morris JC. 1982. “Rates of formation of N-bromo amines in aqueous solution.” Inorg. Chem 21 (12): 4258–4263. 10.1021/ic00142a030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Komaki Y, Kimura SY, Hu HY, Wagner ED, Mariñas BJ, and Plewa MJ. 2014. “Toxic impact of bromide and iodide on drinking water disinfected with chlorine or chloramines.” Environ. Sci. Technol 48 (20): 12362–12369. 10.1021/es503621e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhai H, Zhang X, Zhu X, Liu J, and Ji M. 2014. “Formation of brominated disinfection byproducts during chloramination of drinking water: New polar species and overall kinetics.” Environ. Sci. Technol 48 (5): 2579–2588. 10.1021/es4034765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X, and Zhang X. 2016. “Modeling the formation of TOCl, TOBr and TOI during chlor(am)ination of drinking water.” Water Res. 96 (Jun): 166–176. 10.1016/j.watres.2016.03.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data, models, and code generated or used during the study appear in the published article.