Abstract

Aims/hypothesis

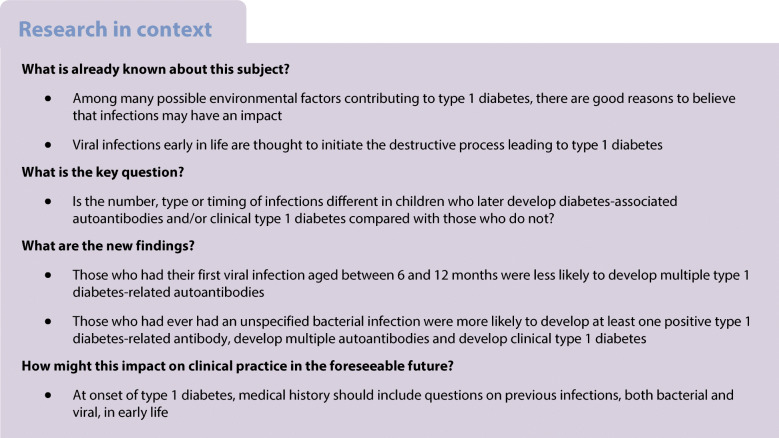

Accumulated data suggest that infections in early life contribute to the development of type 1 diabetes. Using data from the Trial to Reduce IDDM in the Genetically at Risk (TRIGR), we set out to assess whether children who later developed diabetes-related autoantibodies and/or clinical type 1 diabetes had different exposure to infections early in life compared with those who did not.

Methods

A cohort of 2159 children with an affected first-degree relative and HLA-conferred susceptibility to type 1 diabetes were recruited between 2002 and 2007 and followed until 2017. Infections were registered prospectively. The relationship between infections in the first year of life and the development of autoantibodies or clinical type 1 diabetes was analysed using univariable and multivariable Cox regression models. As this study was exploratory, no adjustment was made for multiple comparisons.

Results

Adjusting for HLA, sex, breastfeeding duration and birth order, those who had seven or more infections during their first year of life were more likely to develop at least one positive type 1 diabetes-related autoantibody (p=0.028, HR 9.166 [95% CI 1.277, 65.81]) compared with those who had no infections. Those who had their first viral infection aged between 6 and 12 months were less likely to develop at least one positive type 1 diabetes-related antibody (p=0.043, HR 0.828 [95% CI 0.690, 0.994]) or multiple antibodies (p=0.0351, HR 0.664 [95% CI 0.453, 0.972]). Those who had ever had an unspecified bacterial infection were more likely to develop at least one positive type 1 diabetes-related autoantibody (p=0.013, HR 1.412 [95% CI 1.075, 1.854]), to develop multiple antibodies (p=0.037, HR 1.652 [95% CI 1.030, 2.649]) and to develop clinical type 1 diabetes (p=0.011, HR 2.066 [95% CI 1.182, 3.613]).

Conclusions/interpretation

We found weak support for the assumption that viral infections early in life may initiate the autoimmune process or later development of type 1 diabetes. In contrast, certain bacterial infections appeared to increase the risk of both multiple autoantibodies and clinical type 1 diabetes.

Graphical abstract

Supplementary Information

The online version of this article (10.1007/s00125-022-05786-3) contains peer-reviewed but unedited supplementary material.

Keywords: Autoimmunity, Children, Early infections, TRIGR, Type 1 diabetes

Introduction

Despite modern treatment, type 1 diabetes is a serious disease, with increased morbidity and mortality risk even in patients with good metabolic control [1]. Even in countries with the best available insulin and modern devices, life expectancy may be shortened by several years [2]. The disease cannot be cured, and the incidence has been increasing in many countries around the world [3]. Even though it may theoretically be possible to delay the onset of the disease a few years by treating very high-risk individuals with anti-CD3 monoclonal antibodies before the disease manifests [4], such intervention could only be an option in a very limited group of individuals, and is associated with both adverse events and risks.

For primary prevention, it is necessary to identify the so far unknown cause or causes of the disease. Genetic predisposition is significant [5], but several facts strongly indicate that environmental and/or lifestyle factors play an important role in addition to genetic factors [6]. The incidence of type 1 diabetes has increased significantly over the last few decades [3], which cannot be explained by genetic factors. The impact of environmental factors is supported by the remarkable difference in type 1 diabetes incidence between the Finnish and Russian parts of the Karelia region, whose populations share similar genetics [7], and the finding that migrants tend to show an incidence of type 1 diabetes that is similar to that of the population of their new country [8, 9]. The obvious role of lifestyle or environmental factors is in a way encouraging, as such factors may be modifiable, making it possible not only to stop the increasing incidence but actually to bend the incidence curve downwards again.

Among the many possible environmental factors contributing to type 1 diabetes [6], there is evidence suggesting that infections may have an impact. Epidemiological studies first indicated such a role [10]. Then, when a convincing case history was published 40 years ago showing that Coxsackie virus infection can cause the disease [11], the mystery appeared to be solved. However, unfortunately this is still not the case. We know that maternal infections during pregnancy appear to be associated with type 1 diabetes in the offspring [12], and it has been reported that children who later develop type 1 diabetes more often had infections early in life [13, 14]. Many studies have pointed to enterovirus infections [15–17]. It has been suggested that the infections may initiate the autoimmune process [18–20], but another report suggested that such an infection may accelerate the disease process [21]. Studies also support the importance of infections in precipitating manifest disease, such as increased levels of IgM virus antibodies at the time of diagnosis of type 1 diabetes [22], and the clustering of diagnoses of type 1 diabetes in both time and space [23]. Infectious agents may attack the pancreas, and signs of persistent virus have been detected in the pancreas of patients with newly diagnosed type 1 diabetes [24]. Infections may also influence the immune balance and cause increased insulin demand, which may contribute to manifestation of the disease [25]. It is mostly enteroviruses that have been implicated, but recent studies suggest that upper respiratory tract infections may also be involved [26, 27]. However, despite these supporting pieces of evidence, the picture is far from clear [28]. Many different viruses may play a role as initiating, accelerating and precipitating factors [12]. Bacteria may also be involved, not least via the gut microbiota [29]. Therefore, it is likely that infections during early childhood play a role in the development of type 1 diabetes, but it has been challenging to identify any clear patterns [30]. In an effort to further elucidate the role of such infections, we have used prospectively collected data from the Trial to Reduce IDDM in the Genetically at Risk (TRIGR) study [31]. In this trial, infections were prospectively recorded in a large number of children with genetic susceptibility to type 1 diabetes who were followed from birth until at least the age of 10 years or until diagnosis of type 1 diabetes. We assessed whether the number, type or timing of infections in the first year of life are different in children who later develop diabetes-associated autoantibodies and/or clinical type 1 diabetes compared with those who do not.

Methods

The TRIGR study was an international double-blind multicentre trial designed to determine whether weaning to a hydrolysed infant formula compared with a cow’s milk-based formula reduced the incidence of diabetes-associated autoantibodies and clinical type 1 diabetes in children with an affected first-degree relative and HLA-conferred increased disease susceptibility [29]. A total of 2159 participants were recruited between May 2002 and January 2007, and followed until February 2017 when all children were at least 10 years old [32]. Infections were documented at each participating centre at 12, 18 and 24 months old and annually thereafter during the total duration of follow-up or until the diagnosis of type 1 diabetes. As our aim is to investigate the possible importance of early infections in the first year of life, and whether infections are associated with development of autoantibodies and/or type 1 diabetes, we restricted our study to the group of children who had not developed autoantibodies and/or type 1 diabetes before 12 months old, and who had documented infection data.

None of the participants developed type 2 diabetes, and none who developed type 1 diabetes were autoantibody-negative. Islet cell antibodies (ICA) were detected by use of indirect immunofluorescence in the Scientific Laboratory, Department of Pediatrics, University of Oulu, Oulu, Finland. The disease sensitivity and specificity of the islet cell antibody assay were 100% and 98%, respectively, in the fourth round of the international workshops on standardisation of the islet cell antibody assay [33]. Other diabetes-associated autoantibodies were analysed in a central laboratory (Scientific Laboratory, Children’s Hospital, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland) using samples taken at birth, at 3, 6, 9, 18 and 24 months old, and then annually. Autoantibodies to GAD (GADA), tyrosine phosphatase-related insulinoma-associated 2 molecule (IA-2A), insulin (IAA) and zinc transporter 8 (ZnT8A) were analysed using specific radiobinding immunoassays [34]. The reported disease-specific sensitivity and specificity for each autoantibody were as follows: GADA sensitivity 70–92%, specificity 90–98%; IA-2A sensitivity 62–80%, specificity 93–100%; IAA sensitivity 42–62%, specificity 93–99% [35]. The disease-specific sensitivity and specificity for ZnT8A were 62–74% and 100%, respectively. Type 1 diabetes was diagnosed according to the WHO criteria [36].

Infections as reported by parents were recorded on a standardised adverse event form. The infections were classified as follows: (1) upper respiratory infection, (2) gastroenteritis, (3) urinary tract infection, (4) middle ear infection, (5) pneumonia and (6) other infection.

When infections were categorised as ‘other’, the trial staff were required to specify details in a free text field. Data were also collected on any drug treatments, with antibiotics as a specific category, including the duration of therapy. Based on the clinical description and antibiotic use, infections were classified as bacterial or viral. Infections categorised as ‘other bacterial infections’ are subsequently referred to as ‘unspecified bacterial infections’.

The TRIGR study was approved by the research ethics boards/committees in all participating countries. Parents had given their informed consent, and children provided assent when appropriate for age according to local guidelines. An online repository for TRIGR data is currently not available. The code is maintained at the TRIGR Data Management Unit, University of South Florida. Information is available upon reasonable request from the Data Management Unit.

Statistics

Participant characteristics and variables associated with infections reported during the first year were compared based on antibody status (development of any antibody or multiple [two or more] positive antibodies) and development of type 1 diabetes during follow-up. Categorical variables were compared using the χ2 test unless the number of observations in an individual cell was less than 10, then the Fisher’s exact test was utilised. Continuous variables were compared using the Wilcoxon rank sum test. Univariable Cox regression models based on time to development of any antibody, multiple antibodies and type 1 diabetes were developed using the participant characteristics and infection variables. Multivariable Cox regression models were then applied to adjust for HLA status, sex, breastfeeding duration and birth order. As this study was exploratory, no adjustment was made for multiple comparisons. A p value < 0.05 was considered significant. The data were analysed using SAS software version 9.4 (SAS Institute, USA).

Results

Of those enrolled in TRIGR (n=2159), 2017 were antibody-negative and free of type 1 diabetes at 12 months and had available infection data. Table 1 summarises the characteristics of the study group by antibody and diabetes status. Of the 2017 participants included in this study, 842 (41.7%) developed at least one type 1 diabetes-related antibody, 236 (11.7%) developed multiple antibodies and 134 (6.6%) developed clinical type 1 diabetes. Among the 2017 participants, 537 (26.6%) had no recorded infections, 969 (48.0%) had 1–3 infections, 379 (18.8%) 4–6 infections and 132 (6.5%) had seven or more infections during the first year of life (ESM Table 1). The median (IQR) number of infections per participant was 2 (0–4), with the participants experiencing more viral than bacterial infections: 1 viral infection (0–3) vs 0 bacterial infections (0–1). Of the 2017 participants, 981 (48.6%) had 1–3 viral infections, 248 (12.3%) had 4–6 viral infections and 50 (2.5%) had seven or more viral infections. The incidence of infections increased with increasing age of the infants: 0.41 ± 0.78 up to 3 months, 0.54 ± 0.91 between 3 and 6 months and 1.40 ± 1.74 between 6 and 12 months old (means ± SD). Utilising univariable ANOVAs, the number of infections was related to sex (p=0.034) but not HLA genotype (p=0.302).

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants by antibody and type 1 diabetes status

| Characteristic | AB+ status | Multi-AB+ status | T1D status | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No AB+ (n=1175) |

Any AB+ (n=842) |

p value | Not multi-AB+ (n=1781) |

Multi-AB+ (n=236) |

p value | Did not develop T1D (n=1883) |

Developed T1D (n=134) |

p value | |

| HLA | |||||||||

| HLA-DQB1*0302/DQB1*02 | 241 (20.5) | 227 (27.0) | < 0.001 | 387 (21.7) | 81 (34.3) | < 0.001 | 416 (22.1) | 52 (38.8) | < 0.001 |

| HLA-DQB1*0302/x | 521 (44.3) | 369 (43.8) | 791 (44.4) | 99 (41.9) | 839 (44.6) | 51 (38.1) | |||

| HLA-DQA1*05-DQB1*02/y or HLA-DQA1*03-DQB1*02/y | 413 (35.1) | 246 (29.2) | 603 (33.9) | 56 (23.7) | 628 (33.4) | 31 (23.1) | |||

| Sex | |||||||||

| Female | 569 (48.4) | 393 (46.7) | 0.438 | 854 (48.0) | 108 (45.8) | 0.527 | 893 (47.4) | 69 (51.5) | 0.362 |

| Male | 606 (51.6) | 449 (53.3) | 927 (52.0) | 128 (54.2) | 990 (52.6) | 65 (48.5) | |||

| Breastfeeding duration (months) | |||||||||

| None | 27 (2.3) | 20 (2.4) | 0.426 | 40 (2.2) | 7 (3.0) | 0.288 | 43 (2.3) | 4 (3.0) | 0.528 |

| 0 to < 3 | 914 (77.8) | 641 (76.1) | 1384 (77.7) | 171 (72.5) | 1453 (77.2) | 102 (76.1) | |||

| 3 to < 6 | 212 (18.0) | 156 (18.5) | 318 (17.9) | 50 (21.2) | 345 (18.3) | 23 (17.2) | |||

| 6–9 | 22 (1.9) | 25 (3.0) | 39 (2.2) | 8 (3.4) | 42 (2.2) | 5 (3.7) | |||

| Birth order | |||||||||

| 1st | 627 (53.4) | 445 (52.9) | 0.248 | 959 (53.8) | 113 (47.9) | 0.203 | 1007 (53.5) | 65 (48.5) | 0.077 |

| 2nd | 356 (30.3) | 237 (28.1) | 518 (29.1) | 75 (31.8) | 557 (29.6) | 36 (26.9) | |||

| 3rd or more | 192 (16.3) | 160 (19.0) | 304 (17.1) | 48 (20.3) | 319 (16.9) | 33 (24.6) | |||

Values are n (%)

p values were calculated using χ2 test unless the number of observations in an individual cell was less than 10, then the Fisher’s exact test was utilised

AB+, antibody-positive; T1D, type 1 diabetes

Interestingly, among the 47 infants with no breastfeeding, 28 (59.6%) had no recorded infection during the first year of life and none had seven or more infections; among the 1970 breastfed infants, only 509 (25.8%) had no recorded infection and 132 (6.7%) had seven or more infections (p<0.001). Furthermore, among the breastfed infants, 36.0% had no viral infection recorded in the first year of life, but 59.6% of those who were not breastfed had no viral infection recorded (p<0.004).

Table 2 summarises the number and timing of infections, and Table 3 summarises the types of infections that were reported. In univariable analysis, those who developed at least one positive type 1 diabetes-related autoantibody had more infections (p=0.002) during the first year of life, had more bacterial infections (p=0.005) and had more viral infections (p=0.015). They were more likely to have more infections during the first 3 months of life (p=0.007), and more between months 6 and 12 (p=0.023). They were also more likely to have had an unspecified bacterial infection (p=0.006), more likely to have had an upper respiratory infection (p=0.044) and more likely to have used antibiotics (p=0.013). Autoantibody-positive children were more likely to have experienced their first infection earlier (p=0.021) and their first bacterial infection earlier (p=0.006). Children with multiple autoantibodies more often had any unspecified bacterial infection (p<0.026) and more infections at < 3 months old (p<0.039). Those who developed clinical type 1 diabetes were more likely to have had an unspecified bacterial infection (p=0.003) and to have had an unspecified viral infection (p=0.048) (Table 3). The Kaplan–Meier diagrams in electronic supplementary material (ESM) Figs 1–3 provide further details.

Table 2.

Timing and number of bacterial and viral infections in the first 12 months of life by antibody and diabetes status

| Infection number/timing | AB+ status | Multi-AB+ status | T1D status | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No AB+ (n=1175) |

Any AB+ (n=842) |

p value | Not multi-AB+ (n=1781) |

Multi-AB+ (n=236) |

p value | Did not develop T1D (n=1883) |

Developed T1D (n=134) |

p value | |

| Age at first infection (months) | |||||||||

| None | 338 (28.8) | 199 (23.6) | 0.021 | 474 (26.6) | 63 (26.7) | 0.218 | 498 (26.4) | 39 (29.1) | 0.320 |

| 0 to < 3 | 319 (27.1) | 274 (32.5) | 511 (28.7) | 82 (34.7) | 547 (29.0) | 46 (34.3) | |||

| 3 to < 6 | 251 (21.4) | 177 (21.0) | 383 (21.5) | 45 (19.1) | 406 (21.6) | 22 (16.4) | |||

| 6–12 | 267 (22.7) | 192 (22.8) | 413 (23.2) | 46 (19.5) | 432 (22.9) | 27 (20.1) | |||

| Age at first viral infection | |||||||||

| None | 448 (38.1) | 290 (34.4) | 0.197 | 656 (36.8) | 82 (34.7) | 0.663 | 690 (36.6) | 48 (35.8) | 0.992 |

| 0 to < 3 | 235 (20.0) | 186 (22.1) | 369 (20.7) | 52 (22.0) | 393 (20.9) | 28 (20.9) | |||

| 3 to < 6 | 213 (18.1) | 174 (20.7) | 336 (18.9) | 51 (21.6) | 360 (19.1) | 27 (20.1) | |||

| 6–12 | 279 (23.7) | 192 (22.8) | 420 (23.6) | 51 (21.6) | 440 (23.4) | 31 (23.1) | |||

| Age at first bacterial infection | |||||||||

| None | 752 (64.0) | 484 (57.5) | 0.006 | 1094 (61.4) | 142 (60.2) | 0.096 | 1159 (61.6) | 77 (57.5) | 0.057 |

| 0 to < 3 | 116 (9.9) | 116 (13.8) | 194 (10.9) | 38 (16.1) | 209 (11.1) | 23 (17.2) | |||

| 3 to < 6 | 113 (9.6) | 78 (9.3) | 173 (9.7) | 18 (7.6) | 184 (9.8) | 7 (5.2) | |||

| 6–12 | 194 (16.5) | 164 (19.5) | 320 (18.0) | 38 (16.1) | 331 (17.6) | 27 (20.1) | |||

| Total number of infections | 2 (0–3) | 2 (1–4) | 0.002 | 2 (0–3) | 2 (0–4) | 0.367 | 2 (0–4) | 2 (0–4) | 0.950 |

| Number of viral infections | 1 (0–2) | 1 (0–3) | 0.015 | 1 (0–2) | 1 (0–3) | 0.459 | 1 (0–3) | 1 (0–2) | 0.584 |

| Number of bacterial infections | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–1) | 0.005 | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–1) | 0.492 | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–1) | 0.346 |

| Number of infections at age < 3 months | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–1) | 0.007 | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–1) | 0.039 | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–1) | 0.153 |

| Number of infections at age between 3 and 6 months | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–1) | 0.119 | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–1) | 0.408 | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–1) | 0.911 |

| Number of infections at age between 6 and 12 months | 1 (0–2) | 1 (0–2) | 0.023 | 1 (0–2) | 1 (0–2) | 0.976 | 1 (0–2) | 1 (0–2) | 0.457 |

Values are n (%) for categorical variables and median (IQR) for continuous variables

p values were calculated using χ2 test unless the number of observations in an individual cell was less than 10, then the Fisher’s exact test was utilised. The Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous variables

AB+, antibody-positive; T1D, type 1 diabetes

Table 3.

Type of infection in first 12 months of life by antibody and diabetes status

| Infection type | AB+ status | Multi-AB+ status | T1D status | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No AB+ (n=1175) |

Any AB+ (n=842) |

p value | Not multi-AB+ (n=1781) |

Multi-AB+ (n=236) |

p value | Did not develop T1D (n=1883) |

Developed T1D (n=134) |

p value | |

| No infections | 338 (28.8) | 199 (23.6) | 0.015 | 474 (26.6) | 63 (26.7) | 0.585 | 498 (26.4) | 39 (29.1) | 0.112 |

| Viral only | 110 (9.4) | 91 (10.8) | 182 (10.2) | 19 (8.1) | 192 (10.2) | 9 (6.7) | |||

| Bacterial only | 414 (35.2) | 285 (33.8) | 620 (34.8) | 79 (33.5) | 661 (35.1) | 38 (28.4) | |||

| Viral and bacterial | 313 (26.6) | 267 (31.7) | 505 (28.4) | 75 (31.8) | 532 (28.3) | 48 (35.8) | |||

| Ever had an upper respiratory tract infection | |||||||||

| No | 499 (42.5) | 320 (38.0) | 0.044 | 729 (40.9) | 90 (38.1) | 0.411 | 766 (40.7) | 53 (39.6) | 0.797 |

| Yes | 676 (57.5) | 522 (62.0) | 1052 (59.1) | 146 (61.9) | 1117 (59.3) | 81 (60.4) | |||

| Ever had gastroenteritis | |||||||||

| No | 1006 (85.6) | 707 (84.0) | 0.307 | 1510 (84.8) | 203 (86.0) | 0.619 | 1598 (84.9) | 117 (87.3) | 0.424 |

| Yes | 169 (14.4) | 135 (16.0) | 271 (15.2) | 33 (14.0) | 285 (15.1) | 17 (12.7) | |||

| Ever had a urinary tract infection | |||||||||

| No | 1143 (97.3) | 819 (97.3) | 0.991 | 1729 (97.1) | 233 (98.7) | 0.144 | 1828 (97.1) | 134 (100.0) | 0.048 |

| Yes | 32 (2.7) | 23 (2.7) | 52 (2.9) | 3 (1.3) | 55 (2.9) | 0 (0) | |||

| Ever had a middle ear infection | |||||||||

| No | 926 (78.8) | 655 (77.8) | 0.584 | 1397 (78.4) | 184 (78.0) | 0.868 | 1476 (78.4) | 105 (78.4) | 0.994 |

| Yes | 249 (21.2) | 187 (22.2) | 384 (21.6) | 52 (22.0) | 407 (21.6) | 29 (21.6) | |||

| Ever had pneumonia | |||||||||

| No | 1105 (94.0) | 783 (93.0) | 0.342 | 1667 (93.6) | 221 (93.6) | 0.979 | 1764 (93.7) | 124 (92.5) | 0.601 |

| Yes | 70 (6.0) | 59 (7.0) | 114 (6.4) | 15 (6.4) | 119 (6.3) | 10 (7.5) | |||

| Ever had sepsis | |||||||||

| No | 1166 (99.2) | 833 (98.9) | 0.476 | 1765 (99.1) | 234 (99.2) | 1.000 | 1867 (99.2) | 132 (98.5) | 0.338 |

| Yes | 9 (0.8) | 9 (1.1) | 16 (0.9) | 2 (0.8) | 16 (0.8) | 2 (1.5) | |||

| Ever had any unspecified bacterial infection | |||||||||

| No | 1129 (96.1) | 786 (93.3) | 0.006 | 1698 (95.3) | 217 (91.9) | 0.026 | 1795 (95.3) | 120 (89.6) | 0.003 |

| Yes | 46 (3.9) | 56 (6.7) | 83 (4.7) | 19 (8.1) | 88 (4.7) | 14 (10.4) | |||

| Ever had any unspecified viral infection | |||||||||

| No | 1023 (87.1) | 713 (84.7) | 0.127 | 1529 (85.9) | 207 (87.7) | 0.438 | 1613 (85.7) | 123 (91.8) | 0.048 |

| Yes | 152 (12.9) | 129 (15.3) | 252 (14.1) | 29 (12.3) | 270 (14.3) | 11 (8.2) | |||

| Ever had any other viral infection with fever | |||||||||

| No | 1075 (91.5) | 756 (89.8) | 0.192 | 1616 (90.7) | 215 (91.1) | 0.855 | 1704 (90.5) | 127 (94.8) | 0.098 |

| Yes | 100 (8.5) | 86 (10.2) | 165 (9.3) | 21 (8.9) | 179 (9.5) | 7 (5.2) | |||

| Ever had any antibiotics | |||||||||

| No | 779 (66.3) | 513 (60.9) | 0.013 | 1143 (64.2) | 149 (63.1) | 0.754 | 1209 (64.2) | 83 (61.9) | 0.597 |

| Yes | 396 (33.7) | 329 (39.1) | 638 (35.8) | 87 (36.9) | 674 (35.8) | 51 (38.1) | |||

Values are n (%)

The definition of ‘other’ or ‘unspecified’ infections, bacterial or viral, means those that are not specified elsewhere in the table

p values were calculated using χ2 test unless the number of observations in an individual cell was less than 10, then the Fisher’s exact test was utilised

AB+, antibody-positive; T1D, type 1 diabetes

Adjusting for HLA, sex, breastfeeding duration and birth order, those who had seven or more infections during their first year of life were more likely to develop at least one positive type 1 diabetes-related antibody (p=0.028, HR 9.166 [95% CI 1.277, 65.81]), when compared with those who did not have any infections (ESM Table 2). Those who had their first viral infection between 6 and 12 months old were less likely to develop at least one positive type 1 diabetes-related antibody (p=0.043, HR 0.828 [95% CI 0.690, 0.994]) and multiple antibodies (p=0.035, HR 0.664 [95% CI 0.453, 0.972]) (ESM Table 3). Those who ever had an unspecified bacterial infection during their first year of life were more likely to develop at least one positive type 1 diabetes-related antibody (p=0.013, HR 1.412 [95% CI 1.075, 1.854]), to develop multiple antibodies (p=0.037, HR 1.652 [95% CI 1.030, 2.649]) and to develop clinical type 1 diabetes (p=0.011, HR 2.066 [95% CI 1.182, 3.613]) (Table 4; ESM Table 4).

Table 4.

Univariable and multivariable (adjusted for HLA, gender, breastfeeding duration and birth order) Cox regression results based on time to initial AB+ development, initial multiple AB+ development and type 1 diabetes

| Univariable unadjusted model | Multivariable model | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | HR | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI | p value | HR | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI | p value |

| Any AB+ | ||||||||

| Age at first viral infection (reference = those with no infections in first year) | ||||||||

| < 3 months | 0.909 | 0.756 | 1.093 | 0.313 | 0.928 | 0.771 | 1.117 | 0.430 |

| 3 to < 6 months | 0.952 | 0.789 | 1.149 | 0.610 | 0.997 | 0.825 | 1.205 | 0.979 |

| 6–12 months | 0.823 | 0.686 | 0.988 | 0.036 | 0.828 | 0.690 | 0.994 | 0.043 |

| Number of infections before 3 months (reference = 0) | ||||||||

| 1–3 | 1.088 | 0.941 | 1.257 | 0.255 | 1.093 | 0.945 | 1.265 | 0.229 |

| 4–6 | 0.377 | 0.094 | 1.510 | 0.168 | 0.395 | 0.098 | 1.584 | 0.190 |

| 7 or more | 8.002 | 1.122 | 57.09 | 0.038 | 9.166 | 1.277 | 65.81 | 0.028 |

| Occurrence of any unspecified bacterial infection | 1.379 | 1.051 | 1.808 | 0.020 | 1.412 | 1.075 | 1.854 | 0.013 |

| Multi-AB+ | ||||||||

| Age at first viral infection (reference = those with no infections in first year) | ||||||||

| < 3 months | 0.939 | 0.676 | 1.305 | 0.709 | 0.954 | 0.684 | 1.330 | 0.782 |

| 3 to < 6 months | 0.709 | 0.484 | 1.040 | 0.079 | 0.745 | 0.506 | 1.097 | 0.136 |

| 6–12 months | 0.669 | 0.457 | 0.978 | 0.038 | 0.664 | 0.453 | 0.972 | 0.035 |

| Number of infections between 6 and 12 months (reference = those with no infections) | ||||||||

| 1–3 | 0.752 | 0.573 | 0.988 | 0.041 | 0.760 | 0.578 | 0.999 | 0.049 |

| 4–6 | 0.780 | 0.487 | 1.251 | 0.303 | 0.779 | 0.485 | 1.253 | 0.304 |

| 7 or more | 1.094 | 0.508 | 2.355 | 0.819 | 1.076 | 0.498 | 2.325 | 0.852 |

| Occurrence of any unspecified bacterial infection | 1.620 | 1.014 | 2.589 | 0.044 | 1.652 | 1.030 | 2.649 | 0.037 |

| Development of T1D | ||||||||

| Occurrence of any unspecified bacterial infection | 2.193 | 1.261 | 3.814 | 0.005 | 2.066 | 1.182 | 3.613 | 0.011 |

| Occurrence of any unspecified viral infection | 0.536 | 0.289 | 0.992 | 0.047 | 0.525 | 0.283 | 0.975 | 0.041 |

The definition of ‘other’ or ‘unspecified’ infections, bacterial or viral, means those that are not specified elsewhere in the table

T1D, type 1 diabetes

Discussion

We used prospectively collected data from the TRIGR study [31] to elucidate the importance of early infections for development of type 1 diabetes.

The majority of participating children had some infections, most commonly classified as viral, recorded during the first year of life; most commonly 1–3 infections. Somewhat surprisingly, among the infants who were not breastfed, a majority had no recorded infection at all, and infections were reported less frequently in children who were not breastfed than among breastfed children, although the opposite was expected [37, 38]. One reason may be that a shorter duration of breastfeeding is associated with lower education and psychosocial problems [39], which may be associated with lower rates of reporting infections.

In univariable analysis (Table 2), those who developed at least one positive type 1 diabetes-related autoantibody were more likely to have experienced both more viral and more bacterial infections during the first 3 months of life compared with those who did not. During their first year of life, these participants also had significantly more infections on average, and more frequent use of antibiotics. Participants who developed multiple antibodies were more likely to have had an unspecified bacterial infection, but were less likely to have had a viral infection, while those who progressed to clinical diabetes were more likely to have had either an unspecified bacterial infection or an unspecified virus infection. We found no significant association with frequent use of antibiotics.

When adjusting for HLA, sex, breastfeeding duration and birth order, those who had their first viral infections at between 6 and 12 months old had a decreased risk of both seroconverting to positivity for multiple autoantibodies and developing type 1 diabetes later in childhood compared with those who did not have any infections in their first year. It should be noted that there is previous evidence for the involvement of viral infection in early life, particularly enterovirus, and also for respiratory infections in particular, in the initiation or progression of islet cell autoimmunity [13]. This evidence cannot be discussed in detail here, but, as an example, virome analysis in the TEDDY study showed that prolonged enterovirus B infection rather than independent, short-duration enterovirus B infections (often asymptomatic) was related to the development of islet cell autoimmunity in young at-risk children [40]. However, our initial analyses did consider whether the occurrence of any respiratory tract infection during the first 12 months was predictive of the development of any autoantibody, multiple autoantibodies and the development of type 1 diabetes. Those who developed at least one positive type 1 diabetes-related antibody more often had an upper respiratory infection, but the association with the occurrence of an unspecified bacterial infection was stronger, as was the association with the use of antibiotics.

Thus, in the current study, certain bacterial infections early in life, especially some less frequent bacterial infections, were associated with a significantly increased risk of both developing autoantibodies later and progressing to clinical type 1 diabetes.

Exposure to infections classified as bacterial in early life appeared to be associated with increased risk of developing both multiple autoantibodies and type 1 diabetes. Such infections may not only influence the immune balance, but also the associated antibiotic treatment may affect the gut microbiota [41], which in turn may influence the immune balance. In a large nationwide birth cohort, antibiotic treatment during the first two years of life was not associated with an increased risk of type 1 diabetes later [42]; however, another nationwide study did find that antibiotic treatment increased the risk of presenting with type 1 diabetes before 10 years old [43].

The strengths of our study are the large sample size, the long follow-up and the prospective documentation of infections in a motivated group of parents of high-risk children who had a family member with type 1 diabetes. However, there are limitations. Infections were documented based on parental report, and reporting quality may have been largely variable between families, with a risk of unreported infections and recall bias. Infections were reported as adverse events. In addition, 78 study centres in 15 countries were involved in the TRIGR study, with the consequent possibility of centre- and country-specific differences in reporting practices. These limitations may be an explanation for the surprising finding that no infections during the first year of life were reported for the majority of children who were never breastfed. Another limitation involves classification of the infections. When antibiotics were used, infections were presumed to be bacterial, but many were not confirmed by specific tests, and we have no record of the specific medical diagnoses; classification was based on information provided by the parents, although that information should usually have been verified by the responsible physician. Another problem is the multiple comparisons. As this study was exploratory, no adjustment was made for multiple comparisons. In general, p values < 0.05 were considered significant. However, with stricter requirements for significance, our results tended to favour the importance of bacterial infections over viral infections.

In summary, our results do not support the hypothesis that viral infections in the first year of life initiate the autoimmune process that characterises the development of type 1 diabetes. The finding that those who reported their first viral infection after the age of 6 months had less risk of developing single and multiple autoantibodies compared with those infants who had no infections during in the first year of life implies a protective effect; this fits with the hygiene hypothesis [44] rather than viral infections being a trigger of the autoimmune destruction of the endocrine pancreas. Early life exposure to unspecified bacterial infections appeared to be associated with increased risk of both multiple autoantibodies and type 1 diabetes, possibly via an effect on the intestinal microbiome. In addition, bacterial infections cannot be ruled out as a possible cause of damage to both the exocrine and endocrine pancreas. As this study is post hoc and exploratory by nature, the results require confirmation by other studies.

Supplementary information

(PDF 820 kb)

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the work of all TRIGR investigators (see Appendix in the ESM), and to M. Salonen, Project Coordinator, Biomedicum 2, University of Helsinki, for her outstanding administrative support.

Authors’ relationships and activities

The authors declare that there are no relationships or activities that might bias, or be perceived to bias, their work.

Contribution statement

JL and DC wrote the manuscript, planned the analysis, researched data and contributed to discussion. DC performed the statistical analysis; OK obtained data, initiated and planned the analysis, contributed to the discussion and reviewed/edited the manuscript; MB planned the analysis, contributed to the discussion and reviewed/edited the manuscript. All other authors contributed to acquisition of data, to the discussion and reviewed/edited the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript. JL is the guarantor of this work.

Abbreviations

- GADA

GAD autoantibodies

- IA-2A

Tyrosine phosphatase-related insulinoma-associated 2 molecule autoantibodies

- IAA

Insulin autoantibodies

- TRIGR

Trial to Reduce IDDM in the Genetically at Risk

- ZnT8A

Zinc transporter 8 autoantibodies

Funding

Open access funding provided by Linköping University. This work was supported by grant numbers HD040364, HD042444 and HD051997 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and the Special Statutory Funding Program for Type 1 Diabetes Research administered by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health, USA. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Further support was provided by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the JDRF, the Academy of Finland, a European Foundation for the Study of Diabetes/JDRF/Novo Nordisk focused research grant, and the Commission of the European Communities via the Quality of Life and Management of Living Resources Program (contract number QLK1-2002-00372 ‘Diabetes Prevention’). The content does not necessarily reflect the views of the Commission of the European Communities and in no way anticipates its future policy in this area. The infant formulas used in TRIGR were provided free of charge by Mead Johnson Nutrition.

Data availability

No online repository for TRIGR data is currently available. Information is available upon reasonable request from the TRIGR Data Management Unit at the University of South Florida.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Lind M, Wedel H, Rosengren A. Excess mortality among persons with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:788–789. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1515130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rawshani A, Sattar N, Franzen S, et al. Excess mortality and cardiovascular disease in young adults with type 1 diabetes in relation to age at onset: a nationwide, register-based cohort study. Lancet. 2018;392:477–486. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31506-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tuomilehto J (2013) The emerging global epidemic of type 1 diabetes. Curr Diab Rep 13:795–804. 10.1007/s11892-013-0433-5 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Quattrin T, Haller MJ, Steck AK, et al. Golimumab and beta-cell function in youth with new-onset type 1 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2007–2017. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2006136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pociot F, Lernmark Å. Genetic risk factors for type 1 diabetes. Lancet. 2016;387:2331–2339. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30582-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rewers M, Ludvigsson J. Environmental risk factors for type 1 diabetes. Lancet. 2016;387:2340–2348. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30507-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kondrashova A, Reunanen A, Romanov A, et al. A six-fold gradient in the incidence of type 1 diabetes at the eastern border of Finland. Ann Med. 2005;37:67–72. doi: 10.1080/07853890410018952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Söderström U, Aman J, Hjern A. Being born in Sweden increases the risk for type 1 diabetes – a study of migration of children to Sweden as a natural experiment. Acta Paediatr. 2012;101:73–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2011.02410.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oilinki T, Otonkoski T, Ilonen J, Knip M, Miettinen PJ. Prevalence and characteristics of diabetes among Somali children and adolescents living in Helsinki, Finland. Pediatr Diabetes. 2012;13:176–180. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2011.00783.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gamble DR, Kinsley ML, FitzGerald MG, Bolton R, Taylor KW. Viral antibodies in diabetes mellitus. BMJ. 1969;3:627–630. doi: 10.1136/bmj.3.5671.627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yoon JW, Austin M, Onodera T, Notkins AL. Isolation of a virus from the pancreas of a child with diabetic ketoacidosis. N Engl J Med. 1979;300:1173–1179. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197905243002102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Allen DW, Kim KW, Rawlinson WD, Craig ME. Maternal virus infections in pregnancy and type 1 diabetes in their offspring: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Rev Med Virol. 2018;28(3):e1974. doi: 10.1002/rmv.1974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beyerlein A, Donnachie E, Jergens S, Ziegler AG. Infections in early life and development of type 1 diabetes. JAMA. 2016;315:1899–1901. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.2181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mustonen N, Siljander H, Peet A, et al. Early childhood infections precede development of beta-cell autoimmunity and type 1 diabetes in children with HLA-conferred disease risk. Pediatr Diabetes. 2018;19(2):293–299. doi: 10.1111/pedi.12547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hyoty H, Hiltunen M, Knip M, et al. A prospective study of the role of coxsackie B and other enterovirus infections in the pathogenesis of IDDM. Diabetes. 1995;44(6):652–657. doi: 10.2337/diab.44.6.652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Viskari HR, Roivainen M, Reunanen A, et al. Maternal first-trimester enterovirus infection and future risk of type 1 diabetes in the exposed fetus. Diabetes. 2002;51(8):2568–2571. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.8.2568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Viskari H, Knip M, Tauriainen S, et al. Maternal enterovirus infection as a risk factor for type 1 diabetes in the exposed offspring. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(6):1328–1332. doi: 10.2337/dc11-2389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Salminen K, Sadeharju K, Lönnrot M, et al. Enterovirus infections are associated with the induction of β-cell autoimmunity in a prospective birth cohort study. J Med Virol. 2003;69(1):91–98. doi: 10.1002/jmv.10260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wahlberg J, Fredriksson J, Nikolic E, Vaarala O, Ludvigsson J. Environmental factors related to the induction of beta-cell autoantibodies in 1-yr-old healthy children. Pediatr Diabetes. 2005;6(4):199–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-543X.2005.00129.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rešić-Lindehammer S, Honkanen H, Nix WA, et al. Seroconversion to islet autoantibodies after enterovirus infection in early pregnancy. Viral Immunol. 2012;25:254–261. doi: 10.1089/vim.2012.0022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Christen U, Edelmann KH, McGavern DB, et al. A viral epitope that mimics a self-antigen can accelerate but not initiate autoimmune diabetes. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:1290–1298. doi: 10.1172/JCI200422557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Frisk G, Friman G, Tuvemo T, Fohlman J, Diderholm H. Coxsackie B virus IgM in children at onset of type 1 (insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus: evidence for IgM induction by a recent or current infection. Diabetologia. 1992;35(3):249–253. doi: 10.1007/BF00400925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Samuelsson U, Johansson C, Carstensen J, Ludvigsson J. Space–time clustering in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (IDDM) in south-East Sweden. Int J Epidemiol. 1994;23(1):138–142. doi: 10.1093/ije/23.1.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krogvold L, Edwin B, Buanes T, et al. Detection of a low-grade enteroviral infection in the islets of Langerhans of living patients newly diagnosed with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2015;64:1682–1687. doi: 10.2337/db14-1370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ludvigsson J. Why diabetes incidence increases – a unifying theory. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2006;1079(1):374–382. doi: 10.1196/annals.1375.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lönnrot M, Lynch KF, Elding Larsson H, et al. Respiratory infections are temporally associated with initiation of type 1 diabetes autoimmunity: the TEDDY study. Diabetologia. 2017;60(10):1931–1940. doi: 10.1007/s00125-017-4365-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bélteky M, Wahlberg J, Ludvigsson J. Maternal respiratory infections in early pregnancy increases the risk of type 1 diabetes. Pediatr Diabetes. 2020;21(7):1193–1201. doi: 10.1111/pedi.13075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coppieters KT, Wiberg A, Tracy SM, von Herrath MG. Immunology in the clinic review series: focus on type 1 diabetes and viruses: the role of viruses in type 1 diabetes: a difficult dilemma. Clin Exp Immunol. 2012;168:5–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2011.04554.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dedrick S, Sundaresh B, Huang Q, et al. The role of gut microbiota and environmental factors in type 1 diabetes pathogenesis. Front Endocrinol. 2020;11:78. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2020.00078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cardwell CR, Carson DJ, Patterson CC. No association between routinely recorded infections in early life and subsequent risk of childhood-onset type 1 diabetes: a matched case–control study using the UK General Practice Research Database. Diabet Med. 2008;25:261–267. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2007.02351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.TRIGR Study Group. Akerblom HK, Krischer J, Virtanen SM, et al. The Trial to Reduce IDDM in the Genetically at Risk (TRIGR) study: recruitment, intervention and follow-up. Diabetologia. 2011;54(3):627–633. doi: 10.1007/s00125-010-1964-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Writing Group for the TRIGR Study Group. Knip M, Åkerblom HK, Al-Taji E, et al. Effect of hydrolyzed infant formula vs conventional formula on risk of type 1 diabetes: the TRIGR randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;319(1):38–48. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.19826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Greenbaum CJ, Palmer JP, Nagataki S, et al. Improved specificity of ICA assays in the Fourth International Immunology of Diabetes Serum Exchange Workshop. Diabetes. 1992;12:1570–1574. doi: 10.2337/diab.41.12.1570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Knip M, Åkerblom HK, Becker D, et al. Hydrolyzed infant formula and early β-cell autoimmunity: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;311(22):2279–2278. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.5610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Parkkola A, Härkönen T, Ryhänen SJ, Ilonen J, Knip M. Finnish Pediatric Diabetes Register. Extended family history of type 1 diabetes and phenotype and genotype of newly diagnosed children. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(2):348–354. doi: 10.2337/dc12-0445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alberti KG, Zimmet PZ. Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and its complications, part 1: diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus provisional report of a WHO consultation. Diabet Med. 1998;15:539–553. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9136(199807)15:7<539::AID-DIA668>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Henrick BM, Yao XD, Nasser L, Roozrogousheh A, Rosenthal KL. Breastfeeding behaviors and the innate immune system of human milk: working together to protect infants against inflammation, HIV-1, and other infections. Front Immunol. 2017;8:1631. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sankar MJ, Sinha B, Chowdhury R, et al. Optimal breastfeeding practices and infant and child mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Paediatr. 2015;104:3–13. doi: 10.1111/apa.13147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Scott JA, Binns CW. Factors associated with the initiation and duration of breastfeeding: a review of the literature. Breastfeed Rev. 1999;7(1):5–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vehik K, Lynch KF, Wong MC, et al. Prospective virome analyses in young children at increased genetic risk for type 1 diabetes. Nat Med. 2019;25(12):1865–1872. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0667-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zimmermann P, Curtis N. The effect of antibiotics on the composition of the intestinal microbiota – a systematic review. J Infect. 2019;79(6):471–489. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2019.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Antvorskov JC, Morgen CS, Buschard K, et al. Antibiotic treatment during early childhood and risk of type 1 diabetes in children: a national birth cohort study. Pediatr Diabetes. 2020;21(8):1457–1464. doi: 10.1111/pedi.13111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wernroth ML, Fall K, Svennblad B, et al. Early childhood antibiotic treatment for otitis media and other respiratory tract infections is associated with risk of type 1 diabetes: a nationwide register-based study with sibling analysis. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(5):991–999. doi: 10.2337/dc19-1162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bach JF. Revisiting the hygiene hypothesis in the context of autoimmunity. Front Immunol. 2021;11:615192. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.615192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(PDF 820 kb)

Data Availability Statement

No online repository for TRIGR data is currently available. Information is available upon reasonable request from the TRIGR Data Management Unit at the University of South Florida.