Abstract

In this study, graphene oxide (GO) was functionalized with 3,5-diaminobenzoic acid (DABA) by a one-step method to produce functionalized graphene oxide (FGO). FGO is a new type of absorbent crystalline substance that has a high surface area and a large porosity site as well as a large number of dentate functional groups which lead to enhanced adsorption performance for heavy metal ions. The adsorption efficiency of FGO for Pb+2 and Al+3 metal ions was extra satisfactory when compared with GO due to the ease of design and the homogeneous structure of FGO. The structure of synthesized GO and FGO was confirmed by different techniques such as FTIR, XRD, TGA, BET nitrogen adsorption–desorption methods, and TEM analyses. The mass of utilized adsorbents, the pH of the medium, the concentration of ionic species in the medium, temperature, and process time were all investigated as variables in the adsorbent procedure. The experimental data recorded that the maximum adsorption efficiency of the 0.5 g/L FGO composite was 99.7 and 99.8% for Pb+2 and Al+3 metal ions, respectively, while in the case of using GO, the maximum adsorption efficiency was 92.6 and 91.9% at ambient temperature in a semineutral medium at pH 6 after 4 h. The adsorption results were in good conformity with the Freundlich model and pseudo-second-order kinetics for Pb+2 and Al+3 metal ions. Also, the reusability study indicates that FGO can be used repeatedly at least for five cycles with a slight significant loss in its efficiency.

1. Introduction

Hazardous materials and chemicals affect worldwide water quality and can cause significant health problems in individuals and ecosystems.1,2 Overexploitation of water resources and contamination of freshwater with heavy metals, pesticides, dyes, and other contaminants are linked to the rising world population, resulting in freshwater scarcity.3,4 Heavy metals’ uncontrolled release into the environment and their accumulation in soil and water are severe challenges in terms of environmental quality.5,6 Heavy metal ions such as cadmium (Cd), mercury (Hg), chromium (Cr), arsenic (As), lead (Pb), and others are found in industrial effluents. The toxic profiles of these heavy metal ions and their mobility with different transporting agents, such as microplastics, have negative effects on the natural ecosystem as well as human health.7,8 Heavy metal deposition in the soil can lead to a loss of biodiversity, and heavy metal translocation in plants can lead to changes in plant physiology, antioxidant systems, yield, and nutritional quality.9−11 Lead is a possible carcinogenic substance in humans. The regulatory limit of Pb+2 and Al+3 metal ions in drinking water according to US EPA is 15 ppb and 0.2 ppm, respectively.10 The World Health Organization (WHO) recommended safe limits of Pb+2 and Al+3 in wastewater and soils used for agriculture are 0.01 and 0.1 ppm, respectively.11 Because of the scarcity of fresh water, there is a growing emphasis on the filtration of contaminated water by utilizing new efficient adsorbents and membranes.12 The toxicity of heavy metals in natural environments is determined by several factors, including solution chemistry, source and quantity of contaminants, bioavailability, and the type of exposure.13 Precipitation, ion exchange, oxidation, reduction, membrane filtration, and adsorption are only a few of the traditional water treatment procedures. Adsorption is one of the most promising and extensively utilized technologies in terms of ease of use, efficiency, and cost.14 Adsorption efficiency is directly proportional to adsorbent parameters such as specific surface area and surface functional groups (active adsorption sites). A significant amount of work has gone into developing novel adsorbents for wastewater treatment in recent years. Due to their unique physical and chemical properties, carbon nanomaterials such as carbon nanotubes (CNTs) and graphene and its derivatives such as graphene oxide (GO) have drawn a lot of attention as potential adsorbent materials.15−19 Graphene is a two-dimensional carbon-based nanomaterial made up of a monolayer of sp2-hybridized carbon atoms that are organized in a regular hexagonal pattern.20 Graphene comes in a variety of forms, including pristine graphene, GO, and reduced graphene oxide (RGO). To boost its ion adsorption capacity, graphene requires unique oxidation methods to introduce hydrophilic functional groups. GO is an oxidized version of graphene that can be made by oxidizing graphite. Oxygen molecules intersperse the graphite carbon layers after oxidation.21 Exfoliation increases the interplanar space between the layers, converting graphite to GO. The Hummers and modified Hummers methods for preparing GO from graphite incorporate several oxygen-containing functional groups on the GO surface (hydroxyl and epoxy groups on the basal plane and carboxylic acid groups at the edges of GO). These oxygen-containing functional groups on GO contribute significantly to its hydrophilicity and high negative charge density, both of which are important for heavy metal removal.22 In comparison to other adsorbents such as clay, activated carbon, zeolites, biomaterials, kaolinite, and resins, GO is regarded as the most promising absorbent to adsorb various heavy metal ions. GO has unique physicochemical properties such as higher negative charge density, large surface area, and surface π–π interactions. The functionalization of GO, according to the literature, can increase its adsorption capacity, improve its adsorption selectivity, and make it easier to separate wasted GO from water. Majdoub et al.23 functionalized GO with hexamethylenediamine (HMDA) via amidation processes for very effective Cd(II), Cu(II), and Pb(II) adsorption. The functionalized GO demonstrated significant heavy metal removal efficiency from tap water, with a removal order of Pb, 100% > Cu, 98.18% > Cd, 95.19%. The authors proposed that the electrostatic and chelation interactions between the functional groups of the functionalized GO and the metal cations were responsible for heavy metal adsorption. GO was made from graphite using a modified Hummers process in this study. The 3,5-diaminobenzoic acid (DABA) molecule-functionalized GO sheets were obtained by reacting amino groups with various carboxylic groups at the margins of GO basal planes to generate an FGO composite. The addition of DABA molecules to GO sheets improves not only the wettability of the GO film but also the efficacy of heavy metal ion adsorption.24 The resulting GO and FGO composites were tested for their ability to effectively adsorb heavy metal ions such as Pb+2 and Al+3 metal ions. The impact of experimental variables such as initial concentration, pH, temperature, and immersion time was investigated. The produced GO and FGO composite adsorption isotherms and kinetics were also examined.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Graphite powder (<50 μm), NaNO3, H2SO4 (98%), KMnO4, HCl (37%), H2O2 (30%), 3,5-diaminobenzoic acid (DABA), AlCl3, Pb(CH3COO)2, NH4OH, ethanol, methanol, and acetone were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

2.2. Synthesis of GO

The modified Hummers method was used to synthesize GO.25−27 One gram of graphite powder and 1 g of NaNO3 were typically well combined with 23 mL of 98 wt % H2SO4 and agitated at room temperature for 5–7 min. After this, the mixture was stored in an ice bath at 2–3 °C for 4 h while being constantly stirred. After this, 3 g of KMnO4 was gently added to the aforesaid mixture while stirring continuously, and the temperature was kept at 2–3 °C for 35 min. The combination was then transferred to a reflux system, the temperature was raised to 35 °C, and the mixture was agitated for the next 2 h until the color changed from pink to brownish. The mixture was then swiftly added to 50 mL of deionized water, the temperature was raised to 100 °C, and the mixture was agitated for 1 h until the color turned yellow. Following this, 100 mL of deionized water was added to the mixture and agitated for 30 min before adding 10 mL of H2O2 solution (30 wt %) to eliminate any remaining KMnO4. GO was successfully synthesized and rinsed three times with deionized water to eliminate inorganic contaminants before being dried at 80 °C overnight.28,29

2.3. Fabrication of the FGO Composite

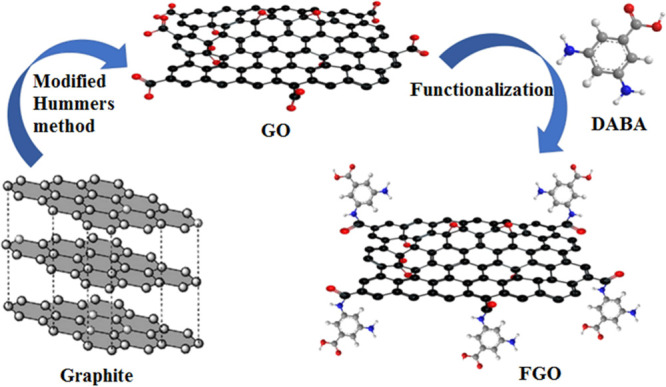

After ultrasonically dispersing 10 mg of GO in 50 mL of ethanol for 0.5 h, 5 mL of 5.0 wt % DABA in water was added and agitated for 24 h at 80 °C, followed by 12 h at room temperature. The FGO composite suspension was filtered, washed multiple times with ethanol, methanol, and acetone, and then dried overnight under a vacuum. The schematic depicts the entire GO and FGO synthesis process, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic procedure of GO and FGO synthesis steps.

2.4. Instruments

A Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectrometer, Nicolet iS10 FTIR spectrometer, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA, was used for infrared (IR) examination. X-ray diffraction (XRD) examination was performed on a PANalytical company model (X’Pert Pro) at 2 range 5–70 with conditions 40 mA, 40 kV, and a copper K1 radiation source ( 0.15418 nm). High-resolution transmission lectron microscopy (HRTEM, JEOL-JEM-2100) at 200 kV was used to examine the morphology of the GO and FGO composite. SDT Q600 V20.5 Build 15 underwent thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) with a flow of dry nitrogen and heating rates of 10 °C/min.

2.5. Heavy Metal Adsorption Experiment

Aluminum and lead ion adsorption behavior was investigated by spreading a known quantity of every adsorbent (GO or FGO) in a 0.5 L Erlenmeyer flask while mixing 250 mL of metal ions liquid (in ppm) at 25 °C with 200 rpm. The adsorbents were filtered through filter paper after treatment, as well as the eluents were preserved for analysis. The influence of solution pH on metal ion adsorption was determined from the measurements in the pH range 1–8, while the influence of temperature was measured in the range of 30–70 °C.30 The pH of the solution was changed by adding diluted NH4OH and HCl solutions. Using 1 g of each adsorbent and starting metal ion concentrations of 50–500 ppm, the influence of heavy metal ion concentration was evaluated. At 500 ppm of initial metal concentration, 1 g of each adsorbent was used to test the impact of immersion time at varied time intervals (30–300 min), while the influence of adsorbent quantity on the adsorption process at 0.02–5 g was investigated. The concentrations of residual metal ions in the solutions following the adsorption process were assessed by atomic absorption spectroscopy in all experiments (PinAAcle-500, Perkin-Elmer, USA). Using eq 1, the proportion of heavy metal ions deposited on the adsorbent (GO and FGO) at equilibrium (qe) was calculated:10

| 1 |

where qe (mg g–1) represents the amount of heavy metal ion adsorbed on the adsorbent at equilibrium, C0 and Ce (mg L–1) represent the initial and equilibrium concentrations of heavy metal ion solution, V (L) represents the volume of heavy metal ion solution, and m (g) represents the mass of the adsorbent. The heavy metal ion removal efficiency (R, %) was calculated using the following equation:10

| 2 |

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characteristics of the Prepared Adsorbents

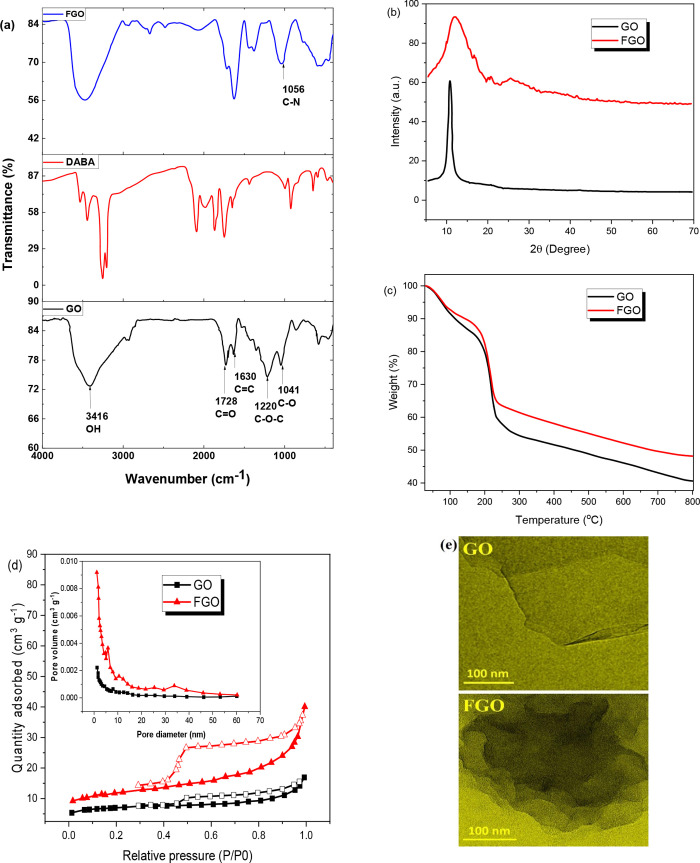

FTIR analysis was used to determine the functional groups at the surface of GO and FGO. FTIR spectra show that GO (Figure 2a) has absorption peaks at 3416 and 1041 cm–1, which are attributed to the stretching vibrations of the O–H and C–O carboxylic acid groups at the edge of GO. Stretching vibrations of the epoxy’s C–O–C groups correspond to the basic mode of vibration of about 1220 cm–1. Furthermore, the peaks at 1630 and 1728 cm–1 show the presence of C=C and C=O, respectively,31 in GO. Overall, all peaks support the GO structure.32 A new distinctive peak for the C–N group found at 1056 cm–1 in the FTIR spectrum of FGO indicated the development of a link between the GO matrix and DABA molecules. Furthermore, due to the conversion of O–H groups to amide groups, the peak intensity of stretching vibrations of O–H groups at 2930 cm–1 was reduced.33,34

Figure 2.

(a) FT-IR spectrum of GO, DABA, and FGO; (b) XRD spectrum; (c) TGA chart; (d) N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms and pore distribution; and (e) TEM images of GO and FGO.

XRD patterns were measured to characterize the crystallographic structure of GO and FGO, as shown in Figure 2b. The crystalline character of the material is demonstrated by the strong diffraction peak at 2θ = 10.7 with the Miller index (001) in the instance of GO. With an interplanar distance of 7.4, this diffraction peak is sufficient to describe GO. The GO characteristic peak vanished after the functionalization of GO to FGO, and a new amorphic pattern at 2θ = 12.5 appeared, confirming the reaction of DABA molecules with GO sheets.35

TGA analysis was used to confirm the thermal stability of the synthesized GO and FGO, as shown in Figure 2c. Up to 120 °C, GO lost 12% of its weight, according to the curve.36 Evaporation of adsorbed water and thermal decompositions of oxygen-containing functional groups such as carboxyl, hydroxyl, epoxy, and ketone could be responsible for the weight loss. Because GO is unstable at high temperatures, the weight loss rate increased to 40% when the temperature was raised to 220 °C.37 Furthermore, the loss rate decreases to a high of around 60 wt % at about 800 °C, implying the presence of structural flaws in GO generated by intense acid oxidation, as indicated in the TGA curve. The FGO weight loss percentage curve was more stable than GO in the range of 12 % up to 200 °C. At around 800 °C, the greatest weight loss of 50% was achieved. Accordingly, it could be concluded that the FGO composite is more thermally stable than GO.

The nitrogen adsorption–desorption technique was used to assess the surface area and pore volume of GO and FGO.38 Both samples have a comparable adsorption isotherm, as shown in Figure 2d. The nitrogen adsorption on all the synthesized adsorbents prepared in this work (GO, FGO) follows a type IV adsorption isotherm according to IUPAC rules. Additionally, all the synthesized adsorbents falling into the mesoporous and microporous materials are typically classified in this way39 (2 nm < pore size <50 nm) according to the pore size values presented in Table 1. Furthermore, the synthesized adsorbents display an H3 hysteresis; adsorbents with this type of hysteresis are usually characterized by aggregates of platelike particles having slit-shaped pores and a wide pore size distribution. Table 1 provides a summary of the textural properties of the synthesized adsorbents. The unmodified GO has a BET surface area of 23.977 m2 g–1, pore volume of 0.024 cm3/g, and pore diameter of 3.588 nm. The lower specific surface area may be attributed to the agglomerations of GO layers during the drying treatment at 100 °C because of the unavoidable van der Waals force between each single sheet of GO.40 Notably, when FCO was compared to GO, the specific surface area, total pore volume, the average pore width of FGO had a slightly higher BET surface area 34.226 m2/g, 0.074 cm3/g and 9.016 nm, respectively. Such increase in the BET surface area and porosity upon the amine functionalization of GO might be attributed to the rearrangement of the exfoliated layers.41 Such a trend has also been reported by other researchers.40,41Figure 2e depicts the TEM morphology of GO and FGO, respectively. A consistent translucent thin layer of the GO structure was visible in the picture of GO.42 The creation of clustered entanglement zones of scattered DABA molecules over the GO sheet surface was seen in a TEM image of FGO.

Table 1. Surface Characteristics of N2 Adsorption–Desorption Isotherms of GO and FGO Adsorbents.

| material | BET surface area (m2g–1) | pore volume (cm3g–1) | pore diameter (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| GO | 23.977 | 0.024 | 3.588 |

| FGO | 34.226 | 0.074 | 9.016 |

3.2. Optimization of Adsorption Parameters

The following parameters impacting the adsorption efficiency of various adsorbents were investigated including initial metal ion concentrations, amounts of adsorbents, pH medium of the adsorption, contact time, and temperature.

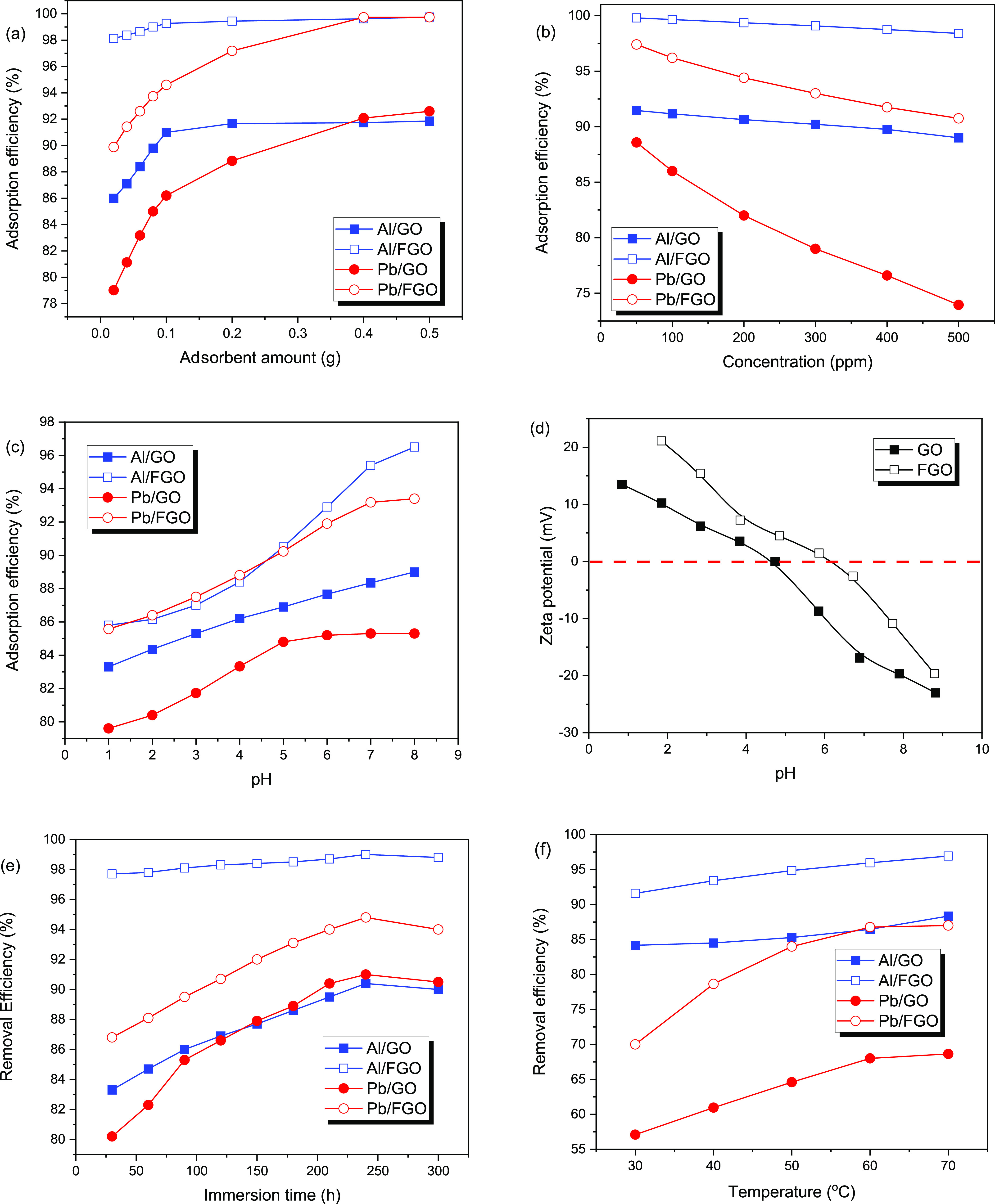

3.2.1. Adsorbent Amounts

The amounts of the adsorbents GO and FGO have a positive effect on the adsorption efficiency of Pb+2 and Al+3 metal ions from their solutions. Figure 3a shows that increasing the adsorbent quantity from 0.02 g to 0.5 g/100 mL of metal ion solution at 500 ppm gradually improves the metal ion adsorption efficiency. Using 0.5 g of GO and FGO adsorbents, maximum adsorption efficiencies for Pb+2 were 92.6 and 99.7%, respectively, and for Al+3 metal ions was 91.9 and 99.7%, respectively. The augmentation in the percentage of active species on adsorbents that may attach to heavy metals in the medium can be attributed to improving the adsorption efficacy of different metals by increasing adsorbent amounts.43,44 The adsorption effectiveness was enhanced dramatically from 0.02 to 0.2 g of adsorbents and then gradually increased. This can also refer to an increase in the number of active sites accessible on the adsorbents.

Figure 3.

Effect of (a) adsorbent amounts; (b) initial concentrations; (c) solution pH; (d) zeta potential; (e) immersion time; and (f) solution temperature of metal ions (Pb(II) and Al(III)) on GO and FGO.

3.2.2. Influence of the Initial Concentration of Pb+2 and Al+3 Metal Ions

The initial concentration of metal ions Pb+2 and Al+3 has a significant impact on the adsorption effect of the GO and FGO adsorbents (Figure 3b). The progressive increase in metal ion concentrations at a certain adsorbent quantity is increasingly saturating these active species. After this, increasing the concentration of Pb+2 and Al+3 ions does not influence the effectiveness of adsorbents in the adsorption process.45 The idea of enhancing heavy metal ion adsorption onto the adsorbent interface is achieved by raising equilibrium adsorption capacity due to increasing the concentration of the heavy metal ion. The metal removal value is higher at lower starting concentrations (50 ppm), and then the efficiency fell to lower levels with increased initial metal ion concentrations (500 ppm). This is because at greater metal ion concentrations, the surface of the adsorbents becomes saturated at a particular value (qe) and the active sites become blocked. As a result, raising the concentration of Pb+2 and Al+3 from 50 to 500 ppm significantly increased the quantity of adsorbed Pb+2 and Al+3 metal ions at equilibrium.

3.2.3. Influence of pH Medium

The solution pH is regarded as a key parameter for the uptake of Pb+2 and Al+3 metal ions from their solution onto adsorbents GO and FGO, because it not only affects the surface charge of GO and FGO and the dissociation of its functional groups but also determines the speciation of Pb+2 and Al+3 metal ions. In addition to this, by studying the adsorption process at different pH values from the acid medium to the basic medium (1–8) at ambient temperature, we can reveal the potential adsorption mechanisms as shown in Figure 3c. The diverse functional groups in the studied adsorbents revealed different behaviors under examination in the wide pH range. The adsorbents include −OH and −NH2 groups that gained positive charges in the acidic solution.46 Also, lead has an oxidation state of Pb+2, while Al has an oxidation state of [Al(H2O)6]3+. In the alkaline or semialkaline medium, lead ions started to precipitate as lead hydroxide (Pb(OH)42–) from the solution, also aluminum ions having the same behaviors forms precipitates as [Al(OH)4]− from the solution,47 making the adsorption studies impossible.48 As shown in Figure 3c, at an acidic medium (pH 1–3), the uptake efficiency of Pb+2 and Al+3 metal ions using the produced GO and FGO adsorbents is poor which can be explained by electrostatic repulsion between H+ and the positively active adsorptive sites, which are mostly hydroxyl groups and carboxyl groups in the case of the GO adsorbent, as well as the aromatic nitrogen moiety of the 3,5-diaminobenzoic acid in FGO is protonated in an acidic solution. Because of the repulsive interactions between the comparable charges, protonated functional groups such as –OH and –NH2are unable to attract positively charged Pb+2 and Al+3 metal ions, as well as the high concentration of Cl– ions which will also compete for the protonated adsorption sites on the FGO surface result in lower Pb+2 and Al+3 metal ion uptake capacity. The adsorption capacity of FGO is strongly affected by the solution pH. Initially, the uptake ability of Pb+2 and Al+3 metal ions significantly increases as the pH values change from 3 to 6. To explain the reasons and provide some valuable information on the adsorption mechanism, the zeta potential of GO and FGO were determined at a pH range of 1–8. It can be seen from Figure 3d that the zeta potential of both the sample decrease with the increase in pH, and their zero potentials are at pH 5 and 6. This indicates that FGO is positively charged in an aqueous solution at pH < 6.

The availability of active species capable of adsorbing positively charged ions rises as the acidity of the medium decreases, and as a result, the adsorption capacity increases. Gradual raises in the pH medium cause deprotonation of the active species at the interface adsorbents, which enhances the inclination of Pb+2 and Al+3 ions, consequently increasing the adsorption effectiveness of adsorbents. When the pH of the media increases, the positively charged metal ion species in the media are transformed into negatively charged metal ion species. The quantity of coordination complexation between the deprotonated active sites (−OH and −NH2) of the adsorbent materials and the negatively charged forms of hydrated metal ions in the solution is increased as a result. The negative charges of the metal ion species were shared with the lone pair of electrons in −OH and −NH2 through coordinating bonds to form complexes between metal ions and adsorbent materials.49,50 This explains why the various adsorbents have increased adsorption effectiveness in a semineutral medium at pH 6.

3.2.4. Contact Time

Contact time refers to how long the adsorbent (GO and FGO) interacts with the Pb+2 and Al+3 ions in the solution. In general, the quantity of absorbed Pb+2 and Al+3 ions from their solutions raises as the immersion time among GO and FGO adsorbent materials increases (Figure 3e). At a short time of 0.5–1.5 h, the adsorption of metal ions is preceded extremely quickly at the beginning of the adsorption reaction. This is owing to the high concentrations of metal ions in the medium and the great number of free adsorption active sites on the adsorbent materials to reach the equilibrium stage.51 The adsorption process slows down as the immersion period is increased, reaching a maximum of 4 h. This implies that the adsorption active species of the various adsorbent materials have been completely occupied. The adsorption effectiveness of the adsorbents in the solutions decreased as they were immersed in the solution longer. This is due to equilibrium among Pb+2 and Al+3 ions packed on the adsorbents and ions present in the medium.52

3.2.5. Influence of Temperature

The influence of heat on the removal effectiveness of adsorbents GO as well as FGO during the removal of Pb+2 and Al+3 ions from their solution was investigated at a neutral medium (pH 6) and the domino effect is shown in Figure 3f. The increase in the temperature solution from 30 to 70 lead to improving the adsorption efficiencies of the adsorbents GO and FGO for the Pb+2 and Al+3 ions. The endothermic character of the adsorption technique was demonstrated by the rise in adsorption efficiency of the examined adsorbent materials when the heat was increased. The temperature rise promotes the adsorption process of Pb+2 and Al+3 ions on the produced adsorbents by several mechanisms. The rate of metal ionic movement from the bulk of the solution to the interface of the adsorbent increases as the temperature rises. Second, when the temperature rises, the functional groups (adsorption active sites) become more ionized, increasing their activity in the adsorption process.53 Lastly, when the temperature rises, the production of metal-adsorbent complexes increases.

3.3. Kinetics Study

Kinetic investigations of GO and FGO as adsorbents during the uptake of Pb+2 and Al+3 ions from their solution were used to find the rate-determining step. The kinetics studies were achieved using an initial metal concentration (Ci) of 500 ppm from Pb+2 and Al+3 ions at pH 6, in the presence of 0.25 g of GO or FGO adsorbents at 25 °C. The residual concentrations of Pb+2 and Al+3 ions after the adsorption (Cf) were measured at various periods (0.5–6 h). Various kinetic models of metal ion adsorption by different adsorbents were well known and widely used, such as pseudo-first-order, pseudo-second-order, and intraparticle diffusion.

3.3.1. Lagergren Pseudo-First-Order Model

The pseudo-first-order model proves that the sorption rate is proportionately dependent on the active site of various adsorbent materials and can be represented according to the following equation:

| 3 |

where, qe and qt (mg/g) represent the concentration of Pb+2 and Al+3 ions at equilibrium and after the time (t), respectively, and k1 (min–1) is a constant rate.

The values of k1 and theoretical concentration adsorption at equilibrium (qe(theo)) for GO and FGO composite adsorbents were calculated using the log( qe – qt) verse the time plot as displayed in Figure 4a. The correlation coefficient, R2 for GO and FGO composites are displayed in Table 2. The results exposed a discrepancy among theoretical and qe experimental values, indicating that the adsorption data did not comply with the pseudo-first-order model.54 Furthermore, the negative numbers in the kinetic profiles indicate that the kinetics do not match the total contact time range, except only appropriate for the first period of the adsorption reaction.55

Figure 4.

(a) Lagergren pseudo-first-order kinetic model. (b) Pseudo-second-order kinetic model. (c) Intraparticle diffusion model for metal ions (Pb(II) and Al(III)) at GO and FGO.

Table 2. Lagergren Pseudo-First-Order Kinetic Model Parameter.

| adsorbent | qe(exp.) (mg/g) | qe(theor.) (mg/g) | k1 (min–1) | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pb | ||||

| GO | 110 | 21 | 1.23 × 10–2 | 0.912 |

| FGO | 121 | 24.3 | 1.71 × 10–2 | 0.825 |

| Al | ||||

| GO | 119 | 3.1 | 8.41 × 10–3 | 0.931 |

| FGO | 127 | 3.5 | 8.28 × 10–3 | 0.942 |

3.3.2. Pseudo-Second-Order Model

To get an appropriate estimate for the kinetics of the adsorption Pb+2 and Al+3 ions at the GO and FGO composite, a pseudo-second-order kinetic model was used according to the following equation.56

| 4 |

where, k2 is the second-order rate constant (g/mg min), qe and qt (mg/g) indicated the concentration of Pb+2 and Al+3 ions at equilibrium and after the time t, respectively.

The values of k2 and theoretical concentration adsorption at equilibrium (qe(theor.)) for GO and FGO composite adsorbents were calculated using the linear plot between t/qt versus time as displayed in Figure 4b. The correlation coefficient, R2 for GO and FGO composites are displayed in Table 3. Obviously, the adsorption reaction for Pb+2 and Al+3 ions is not expected to be pseudo-first-order since the value of qe(exp.) is not equivalent to the value of qe(theoretical), irrespective of the magnitude of the correlation coefficient. In the situation of pseudo-second-order, the values of qe(exp.) and qe(theor.) are quite similar, with the correlation coefficient value nearly equal to unity, so the adsorption reaction processes agree very well with the pseudo-second-order kinetics for Pb+2 and Al+3 ions. This also supports the pseudo-second-order model’s concept that metal ion absorption is caused by chemisorption using valence forces via electron sharing or exchange between adsorbent active sites (functional group) and adsorbates (Pb+2 and Al+3 ions).57

Table 3. Kinetic Parameters Based on the Pseudo-Second-Order Kinetic Model.

| adsorbent | qe(exp.) (mg/g) | qe(theor.) (mg/g) | k1 (min–1) | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pb | ||||

| GO | 110 | 105 | 1.22 × 10–3 | 0.962 |

| FGO | 121 | 119 | 1.34 × 10–3 | 0.995 |

| Al | ||||

| GO | 119 | 112 | 8.5 × 10–3 | 1 |

| FGO | 127 | 121 | 9.75 × 10–3 | 0.9996 |

3.3.3. Intraparticle Diffusion Model

Adsorption occurs in a multistep process regulated by single or extra processes, such as external dispersion or surface dispersion in which the metal ion transfer from the bulk of medium to the adsorbent interface, adsorbed species film formation, and finally the diffusion of adsorbed species into the different adsorbent pores interact with the adsorptive sites. The intraparticle diffusion model described adsorption processes in which the rate of diffusion is determined by the rate at which the adsorbate disperses to the adsorbent. This is obtainable by the following equation58

| 5 |

where qt (mg/g) is the concentration of Pb+2 and Al+3 ions adsorbed at GO and FGO composites after time t and kint is the intraparticle diffusion step rate constant in mg/g min1/2. When intraparticle diffusion models were included in the overall adsorption reaction, the diagram of qt versus t1/2 must be linear, and we can calculate the kint value from the slope of the linear equation. If the graph’s plot passes through to the origin, it is established that intraparticle diffusion is the rate-controlling step in the adsorption reaction. Figure 4c provides a multilinearity relation that highlighted the attendance of two stages that happen through the adsorption reaction; the initial stage is represented by a linear profile that indicates the intraparticle diffusion of Pb+2 and Al+3 ions through the pores of GO and FGO composite adsorbents, while the second stage was the plateau region which corresponds to the equilibrium at the adsorbents/solution interfaces (kint). The rate constants of the described stages and the R2 values are shown in Table 4. The data showed a trend in the adsorption process by GO and FGO composite adsorbents can be discussed through the value of intraparticle diffusion constant of the second stage (k2int), that meaning the second step is the lowest rate constant because it is the last stability stage in which intraparticle diffusion begins to slow down due to the very low Pb+2 and Al+3 ions concentration remaining in solution.

Table 4. Kinetic Parameters Based on the Intraparticle Diffusion Model Exhibit Multilinearity; Two Stages of Multilinearity Are Shown, k1 and k2.

| adsorbent | first stage |

second stage |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| k1int (mg/g min1/2) | R2 | k2int (mg/g min1/2) | R2 | |

| Pb | ||||

| GO | 1.22 | 0.987 | 1.08 | 0.999 |

| FGO | 1.13 | 0.999 | 0.859 | 0.994 |

| Al | ||||

| GO | 0.26 | 0.972 | 0.16 | 0.992 |

| FGO | 0.271 | 0.995 | 0.137 | 0.994 |

3.4. Adsorption Isotherm

To completely comprehend the adsorption mechanism, the adsorption isotherm is required. The adsorption isotherm provides important information on how the adsorbate particles disperse among the solution and adsorbent interface. A variety of adsorption isotherms may be utilized to correlate the adsorption equilibrium in heavy metal adsorption on various adsorbents. The most common and practical isotherms which can be used to explain the experimental data of Pb+2 and Al+3 ion adsorption from their medium using various adsorbents are the Langmuir, Freundlich, and Temkin adsorption isotherm models. In the adsorption process, the Langmuir adsorption isotherm model involves two major points. First, adsorption occurs in the adsorbent at specified homogenous adsorption sites. Second, once adsorbed metal ions establish a saturated film on the adsorbent surface, maximum monolayer adsorption occurs. The Langmuir isotherm was used to calculate the experimental data which is represented by the following equation:59

| 6 |

where Ce, qe, and qmax are the concentsration of metal ions at equilibrium (mg/L), the adsorbed metal ion (mg/g), and the metal ion concentration at complete monolayer formation (mg g–1), respectively, kl is the Langmuir adsorption constant (L mg–1). Figure 5a,b represents the Langmuir adsorption isotherm and the fitted data are listed in Table 5. From the data illustrated in Table 5, R2 (Langmuir correlation coefficient) was located between 0.409 and 0.9007, which did not match the actual findings.

Figure 5.

(a,b) Langmuir, (c,d) Temkin, and (e,f) Freundlich isotherm models for adsorption of Al(III) and Pb(II) at GO and FGO.

Table 5. Langmuir and Freundlich Model Parameters of Pb(II) and Al(III) Adsorption on GO and FGO Adsorbents.

| metal

ion |

Pb(II) |

Al(III) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| adsorbent | GO | FGO | GO | FGO | |

| Langmuir model | equation of state | y = −0.031x + 3.655 | y = −0.031x + 1.769 | y = −0.008x + 0.216 | y = −0.001x + 0.074 |

| R2 | 0.868 | 0.9007 | 0.634 | 0.409 | |

| Freundlich model | equation of state | y = 2.076x + 1.414 | y = 1.884x + 1.737 | y = 1.420x + 0.491 | y = 1.155x + 1.128 |

| R2 | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.987 | 0.979 | |

| kf (mg/g) | 25.94179 | 54.57579 | 3.097419 | 13.42765 | |

| n | 0.48 | 0.53 | 0.7 | 0.89 | |

| Temkin model | equation of state | y = 82.778x – 221.57 | y = 62.837x – 202.43 | y = 66.802x – 65.951 | y = 51.933x + 0.2666 |

| R2 | 0.887 | 0.862 | 0.953 | 0.913 | |

The Temkin isotherm model includes the heat of adsorption reduction in various adsorbent layers probably caused by the interaction between adsorbents and adsorbates. The linear form of the Temkin isotherm is represented by the following equation:

| 7 |

where Ce (mg L–1) is the concentration of metal ions at equilibrium, KT is the Temkin isotherm constant (L g–1) corresponding to maximum binding energy, and B = RT/bT in which b is the Temkin constant related to the heat of adsorption (J mol–1) and R and T are the gas constant (8.314 J K mol–1) and absolute temperature (K), respectively. The linear fits for the Temkin isotherm models are shown in Figure 5c,d, and their corresponding calculated parameters are listed in Table 5. The data reported in Table 5 show that R2 (Temkin correlation coefficient) ranged between 0.862 and 0.953, which did not contest the definite findings.

The results also were adapted with the Freundlich adsorption isotherm model using the following equation,60 and the fitted data are shown in Table 5.

| 8 |

where, kf (L g–1) is the coefficient of Freundlich adsorption and n is the constant associated with the adsorption power and intensity of reactive sites, respectively. The Freundlich model has two parameters: kf and n. The amount of Pb+2 and Al+3 ions adsorbed at GO and FGO composites at equilibrium is represented by kf, which is proportional to the adsorption capacity of the metal ions on the various adsorbents. n denotes the strength of adsorption of metal ions at the surface of the adsorbent. The n values were between 1 and 10 which indicates moderately significant adsorption. The obtained n values in the examined adsorbents were more than 1, indicating rather high metal ion adsorption on the adsorbents.

The Freundlich model (Figure 5e,f) shows the greatest fit for the experimental data during the adsorption reaction of Pb+2 and Al+3 ions using GO and FGO composites with correlation factors (R2) ranging between 0.999 and 0.979. Correlation factors are too near to one (1.0). This indicates that the Freundlich model is extremely closely matched to the adsorption process. Freundlich adsorption coefficients (kf) were 25.94 and 3.09 for Pb+2 and Al+3 ions, respectively, in the case of GO. The values of the Freundlich adsorption coefficient (kf) were improved by modifying the chemical construction of GO to achieve 54.57 and 13.42 for Pb+2 and Al+3 ions, respectively, for FGO. The introduction of the 3,5-diaminobenzoic acid precursor in the frame construction of GO improved the adsorption potential of GO according to the adsorption isotherm analysis. Also, the values of n have the same trend as kf which increase with the chemical modification of GO.61,62 This suggested a significant action among the deposited metal ions and the FGO adsorbent surface additionally, and in our study, the n values were typically less than unity, which shows the uniformity or variability of the adsorption sites as adsorbent surfaces. This shows that the active sites connected to Pb+2 and Al+3 ions are more heterogeneous.

3.5. Adsorption Mechanism

Because GO can produce a significant number of hydroxyl and carboxyl moieties on the surface of GO through its synthesis, it becomes hydrophilic in an aqueous solution.63,64 To join the amine groups of DABA and GO, the amidation reaction was used. The electrostatic attraction between positive charges of heavy metal ions and negative charges of lone pair electron clouds of hydroxyl, carboxyl, and amine moieties on the adsorbent’s surface can be employed to explain the heavy metal adsorption reaction.65−67 The huge specific surface area of the FGO composite, on the other hand, could be another reason for finishing the adsorption process. The increased specific surface area of heavy metal ions results in higher adsorption capability.68−71 The molecular geometry optimization data can be used to investigate the mechanism of metal adsorption. The metal ions in the solution are positively charged species that are easily attracted to the highest potential centers of the adsorbent framework. In FGO, the amine center groupings are related to the more active and highly charged adsorptive center. Metal ions are more attracted to these core groups.72 As a result, metal ions are the first to produce saturation of the core group. Adsorption then takes place on another atom center. Therefore, the introduction of DABA groups on the GO surface could dramatically increase the active adsorption sites of FGO.

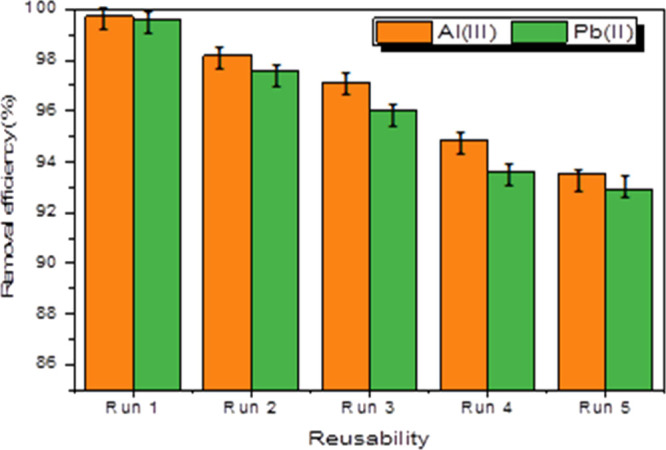

3.6. Reusability and Stability of FGO

The reusability and stability studies are critical in minimizing wastewater treatment costs because they indicate a suitable adsorbent that can be utilized in the long run with a larger adsorbent. Therefore, the ability to recycle FGO was thoroughly examined. The FGO concentration was 0.5 g/L, the target metal ion concentrations were 50 mg/L, and the pH was set to 6. The ions of Pb+2 and Al+3 were desorbed with EDTA (0.1 mol/L) and 1 M HCl solution. The adsorption experiment was done five times under optimal conditions. Figure 6 depicts the adsorption capacity difference. It is possible to see that the adsorption ability reduced little as the adsorption cycle lengthened. The adsorption capacity of FGO for Pb+2 and Al+3 ions after five adsorption runs was 90.5 and 91.8%, respectively, at the optimum reaction conditions (pH = 6, initial metal ion concentration = 50 ppm, adsorbent dose = 0.5 g L–1, residence time = 4 h at ambient temperature as shown in Figure 6). This could be due to active site destruction and FGO mass loss during desorption. The FGO adsorbent, in general, is a reusable adsorption material that efficiently adsorbs Pb+2 and Al+3 ions from the solution.

Figure 6.

Reusability of FGO during metal adsorption.

3.7. Adsorption of Heavy Metals from Industrial Wastewater

The adsorption process of FGO adsorbents in simulated Pb+2 and Al+3 ion effluents has been regularly investigated in a laboratory, while only a few studies have looked at heavy metals in manufacturing wastewater using adsorbents.73 FGO adsorption capability for Pb+2 and Al+3 ions shows that it has considerable promise for heavy metal treatment in industrial effluents. Accordingly, the appliance of the FGO sorbent was studied with a manufacturing wastewater sample from a metal smelting plant in Egypt. The chemical analysis of the wastewater sample showed that the initial concentrations of Pb+2, Al+3, Cu+2, Cd+2, Zn+2, Cl–, Na+, SO42– ions, and total rare earth elements were 7.59, 15.47, 4.5, 5.3, 12.7, 4300, 40, 2100, and 200 g/L, respectively. Filtration was used to decline solid materials, and the pH of the manufacturing effluent was attuned to 6.0 with HCl. The adsorption process was carried out by adding FGO (0.4 g/L) into the manufacturing effluent (20 mL) at ambient temperature for 240 min. The concentrations of Pb+2, Al+3, Cu+2, Cd+2, Zn+2, Cl–, Na+, SO42– ions, and total rare earth element after adsorption were 0.5, 12.24, 2.48, 3.71, 11.2, 4050, 39.80, 1840, and 180 g/L, respectively. According to these results, the produced FGO was effective in recovering both metal ions from waste effluents, with a 93.4% recovery efficiency for Pb+2 ions whereas 79.19% for Al+3 ions with adsorption of a small number of interfering components.

3.8. Comparison of Maximum Removal Efficiency of Pb+2 and Al+3 Ions

When compared to recently published GO-based composites, FGO’s adsorption removal or capacity for Pb+2 and Al+3 ions is similar and acceptable as given in Table 6. As a result, FGO may be suitable as a successful eliminator and practical for the removal of Pb+2 and Al+3 ions from aqueous effluents.

Table 6. Comparison of Maximum Pb(II) and Al(III) Removal Efficiency (%) by FGO with Recently Reported GO-Based Composites.

| name of GO-based composites | removal efficiency (%) | experimental conditions | ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pb(II) | |||

| Ag–CoFe2O4–GO nanocomposite | 75 | pH = 4–7, initial concentration = 20 ppm, adsorbent dose = 3.00 g L–1, residence time = 24 h | (74) |

| aluminum-based MOF-GO | 72.0 | pH = 6, initial concentration = 300 ppm, adsorbent dose = 50 mg L–1, residence time = 100 min | (75) |

| metal-resistant/adapted fungus penicillium janthinillum and GO and activated carbons | 53–95 | pH = 6 ± 0.2, initial concentration = 25 ppm, adsorbent dose = 0.5 g L–1, residence time = 12 h | (76) |

| porous Gd2O3-doped GO | 96.4 | pH = 5, initial concentration = 40 ppm, adsorbent dose = 0.5 g L–1, residence time = 24 h | (77) |

| Fe3O4@C–GO nanocomposite | 78.0 | pH = 7, initial concentration = 100 ppm, adsorbent dose = 0.5 g L–1, residence time = 77 min | (78) |

| FGO | 99.7 | pH = 6, at initial concentration = 50 ppm, adsorbent dose = 0.5 g L–1, ambient temperature, residence time = 4 h | our study |

| Al(III) | |||

| graphene oxide–ZnO nanocomposites | 95.6 | pH = 6, initial concentration = 80 ppm, adsorbent dose = 0.8 g L–1, residence time = 8 h | (79) |

| natural clay adsorbent | 98.95 | pH = 5, initial concentration = 100 ppm, adsorbent dose = 0.5 g L–1, residence time = 16 h | (80) |

| coconut shell adsorbent | 92.83 | pH = 6, initial concentration = 150 ppm, adsorbent dose = 0.5 g L–1, residence time = 8 h | (81) |

| rice hull-activated carbon | 96.63 | pH = 6, initial concentration = 100 ppm, adsorbent dose = 0.7 g L–1, residence time = 6 h | (82) |

| nut shell activated carbon | 78.20 | pH = 7, initial concentration = 40 ppm, adsorbent dose = 0.6 g L–1, residence time = 24 h | (83) |

| FGO | 99.8 | pH = 6, at initial concentration = 50 mg L–1, adsorbent dose = 0.5 g L–1, ambient temperature, residence time = 4 h | our study |

4. Conclusions

This research creates an FGO adsorbent by combining GO composites with 3,5-diaminobenzoic acid (DABA) for the uptake of Pb+2 and Al+3 ions. The affluence of several parameters on adsorption performance was investigated, and the outcomes revealed that the FGO composite has a higher adsorption capacity than individual GO. The Freundlich model is the fitting isotherm model for the adsorption equilibrium, and the pseudo-second-order model may achieve the adsorption kinetic process. The FGO composite had adsorption capacities of 99.7 and 99.8%, respectively, for Pb+2 and Al+3 ions, compared to 92.6 and 91.9% for GO. Quantum calculations demonstrate that metal ions in solutions containing positively charged species are easily attracted to the adsorbent framework’s highly potential centers. The adsorption capacity of FGO for Pb+2 and Al+3 ions after five adsorption runs was 90.5 and 91.8%, respectively. These results suggest that the FGO composite could be used to remove Pb+2 and Al+3 ions from the aqueous solution which achieves good stability and satisfactory applicability.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Taif University Researcher Supporting Project number (TURP-2020/243), Taif University, Taif, Saudi Arabia. Also, they thank Egyptian Petroleum Research Institute (EPRI) and Chemistry Department, Faculty of Science, Cairo University for their support.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Shen C.; Zhao Y.; Li W.; Yang Y.; Liu R.; Morgen D. Global Profile of Heavy Metals and Semimetals Adsorption Using Drinking Water Treatment Residual. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 372, 1019–1027. 10.1016/j.cej.2019.04.219. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y.; Yue Y.; Zhang H.; Cheng F.; Zhao W.; Rao J.; Luo S.; Wang J.; Jiang X.; Liu Z.; Liu N.; Gao Y. 3D Synergistical MXene/Reduced Graphene Oxide Aerogel for a Piezoresistive Sensor. ACS Nano 2018, 12, 3209–3216. 10.1021/acsnano.7b06909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofste R. W.; Reig P.; Schleifer L.. 17 Countries, Home to One-Quarter of the World’s Population, Face Extremely High Water Stress; World Resources Institute, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zou Y.; Wang X.; Khan A.; Wang P.; Liu Y.; Alsaedi A.; Hayat T.; Wang X. Environmental Remediation and Application of Nanoscale Zero-Valent Iron and Its Composites for the Removal of Heavy Metal Ions: A Review. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 7290–7304. 10.1021/acs.est.6b01897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amer A.; Sayed G. H.; Ramadan R. M.; Rabie A. M.; Negm N. A.; Farag A. A.; Mohammed E. A. Assessment of 3-Amino-1H-1,2,4-Triazole Modified Layered Double Hydroxide in Effective Remediation of Heavy Metal Ions from Aqueous Environment. J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 341, 116935 10.1016/j.molliq.2021.116935. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Potapowicz J.; Szumińska D.; Szopińska M.; Polkowska Ż. The Influence of Global Climate Change on the Environmental Fate of Anthropogenic Pollution Released from the Permafrost: Part I. Case Study of Antarctica. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 651, 1534–1548. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.09.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z.; Sim A.; Urban J. J.; Mi B. Removal and Recovery of Heavy Metal Ions by Two-Dimensional MoS2 Nanosheets: Performance and Mechanisms. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 9741–9748. 10.1021/acs.est.8b01705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao G.; Li J.; Ren X.; Chen C.; Wang X. Few-Layered Graphene Oxide Nanosheets As Superior Sorbents for Heavy Metal Ion Pollution Management. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 10454–10462. 10.1021/es203439v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng G.; He Y.; Zhan Y.; Zhang L.; Pan Y.; Zhang C.; Yu Z. Novel Polyvinylidene Fluoride Nanofiltration Membrane Blended with Functionalized Halloysite Nanotubes for Dye and Heavy Metal Ions Removal. J. Hazard. Mater. 2016, 317, 60–72. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2016.05.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yap P. L.; Kabiri S.; Tran D. N. H.; Losic D. Multifunctional Binding Chemistry on Modified Graphene Composite for Selective and Highly Efficient Adsorption of Mercury. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 6350–6362. 10.1021/acsami.8b17131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao Z.; Huang X.; Yang F.; Zhao W.; Zhou X.; Zhao C. Engineering Sodium Alginate-Based Cross-Linked Beads with High Removal Ability of Toxic Metal Ions and Cationic Dyes. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 187, 85–93. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.01.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu P.; Borrell P. F.; Božič M.; Kokol V.; Oksman K.; Mathew A. P. Nanocelluloses and Their Phosphorylated Derivatives for Selective Adsorption of Ag+, Cu2+ and Fe3+ from Industrial Effluents. J. Hazard. Mater. 2015, 294, 177–185. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2015.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H.; Wang Y.; Zhao W.; Xiong G.; Cao X.; Dai Y.; Le Z.; Zhang Z.; Liu Y. Phosphorylation of Graphehe Oxide to Improve Adsorption of U(VI) from Aquaeous Solutions. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2017, 313, 175–189. 10.1007/s10967-017-5274-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ersan G.; Apul O. G.; Perreault F.; Karanfil T. Adsorption of Organic Contaminants by Graphene Nanosheets: A Review. Water Res. 2017, 126, 385–398. 10.1016/j.watres.2017.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konno Y.; Farag A. A.; Tsuji E.; Aoki Y.; Habazaki H. Formation of Porous Anodic Films on Carbon Steels and Their Application to Corrosion Protection Composite Coatings Formed with Polypyrrole. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2016, C386. 10.1149/2.1451607jes. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mehmeti V.; Halili J.; Berisha A. Which Is Better for Lindane Pesticide Adsorption, Graphene or Graphene Oxide? An Experimental and DFT Study. J. Mol. Liq. 2022, 347, 118345 10.1016/j.molliq.2021.118345. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Gamal A. G.; Chowdhury T. H.; Kabel K. I.; Farag A. A.; Abd El-Sattar N. E. A.; Rabie A. M.; Islam A. N-Functionalized Graphene Derivatives as Hole Transport Layers for Stable Perovskite Solar Cell. Sol. Energy 2021, 228, 670–677. 10.1016/j.solener.2021.10.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Altalhi A. A.; Mohammed E. A.; Morsy S. S. M.; Negm N. A.; Farag A. A. Catalyzed Production of Different Grade Biofuels Using Metal Ions Modified Activated Carbon of Cellulosic Wastes. Fuel 2021, 295, 120646 10.1016/j.fuel.2021.120646. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Gamal A. G.; Farag A. A.; Elnaggar E. M.; Kabel K. I. Comparative Impact of Doping Nano-Conducting Polymer with Carbon and Carbon Oxide Composites in Alkyd Binder as Anti-Corrosive Coatings. Compos. Interfaces 2018, 25, 959. 10.1080/09276440.2018.1450578. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Allen M. J.; Tung V. C.; Kaner R. B. Honeycomb Carbon: A Review of Graphene. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 132–145. 10.1021/cr900070d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apul O. G.; Wang Q.; Zhou Y.; Karanfil T. Adsorption of Aromatic Organic Contaminants by Graphene Nanosheets: Comparison with Carbon Nanotubes and Activated Carbon. Water Res. 2013, 47, 1648–1654. 10.1016/j.watres.2012.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amadei C. A.; Montessori A.; Kadow J. P.; Succi S.; Vecitis C. D. Role of Oxygen Functionalities in Graphene Oxide Architectural Laminate Subnanometer Spacing and Water Transport. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 4280–4288. 10.1021/acs.est.6b05711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majdoub M.; Amedlous A.; Anfar Z.; Jada A.; El Alem N. Engineering of Amine-Based Binding Chemistry on Functionalized Graphene Oxide/Alginate Hybrids for Simultaneous and Efficient Removal of Trace Heavy Metals: Towards Drinking Water. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2021, 589, 511–524. 10.1016/j.jcis.2021.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra A. K.; Ramaprabhu S. Functionalized Graphene Sheets for Arsenic Removal and Desalination of Sea Water. Desalination 2011, 282, 39–45. 10.1016/j.desal.2011.01.038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yap P. L.; Kabiri S.; Auyoong Y. L.; Tran D. N. H.; Losic D. Tuning the Multifunctional Surface Chemistry of Reduced Graphene Oxide via Combined Elemental Doping and Chemical Modifications. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 19787–19798. 10.1021/acsomega.9b02642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcano D. C.; Kosynkin D. V.; Berlin J. M.; Sinitskii A.; Sun Z.; Slesarev A.; Alemany L. B.; Lu W.; Tour J. M. Improved Synthesis of Graphene Oxide. ACS Nano 2010, 4, 4806–4814. 10.1021/nn1006368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hummers W. S.; Offeman R. E. Preparation of Graphitic Oxide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1958, 80, 1339–1339. 10.1021/ja01539a017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kabel K. I.; Farag A. A.; Elnaggar E. M.; Al-Gamal A. G. Improvement of Graphene Oxide Characteristics Depending on Base Washing. J. Superhard Mater. 2015, 37, 327. 10.3103/S1063457615050056. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kabel K. I.; Farag A. A.; Elnaggar E. M.; Al-Gamal A. G. Removal of Oxidation Fragments from Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes Oxide Using High and Low Concentrations of Sodium Hydroxide. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2016, 41, 2211–2220. 10.1007/s13369-015-1897-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hoseinzadeh H.; Hayati B.; Shahmoradi Ghaheh F.; Seifpanahi-Shabani K.; Mahmoodi N. M. Development of Room Temperature Synthesized and Functionalized Metal-Organic Framework/Graphene Oxide Composite and Pollutant Adsorption Ability. Mater. Res. Bull. 2021, 142, 111408 10.1016/j.materresbull.2021.111408. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Negm N. A.; Abubshait H. A.; Abubshait S. A.; Abou Kana M. T. H.; Mohamed E. A.; Betiha M. M. Performance of Chitosan Polymer as Platform during Sensors Fabrication and Sensing Applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 165, 402–435. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.09.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang J.; Pham V. H.; Hur S. H.; Chung J. S. Dispersibility of Reduced Alkylamine-Functionalized Graphene Oxides in Organic Solvents. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2014, 424, 62–66. 10.1016/j.jcis.2014.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilfong W. C.; Srikanth C. S.; Chuang S. S. C. In Situ ATR and DRIFTS Studies of the Nature of Adsorbed CO2 on Tetraethylenepentamine Films. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 13617–13626. 10.1021/am5031006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farag A. A.; Eid A. M.; Shaban M. M.; Mohamed E. A.; Raju G. Integrated Modeling, Surface, Electrochemical, and Biocidal Investigations of Novel Benzothiazoles as Corrosion Inhibitors for Shale Formation Well Stimulation. J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 336, 116315 10.1016/j.molliq.2021.116315. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J.; Chen Y.; Yu H.; Yan L.; Du B.; Pei Z. Removal of Cu2+, Cd2+ and Pb2+ from Aqueous Solutions by Magnetic Alginate Microsphere Based on Fe3O4/MgAl-Layered Double Hydroxide. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2018, 532, 474–484. 10.1016/j.jcis.2018.07.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altalhi A. A.; Mohamed E. A.; Morsy S. M.; Abou Kana M. T. H.; Negm N. A. Catalytic Manufacture and Characteristic Valuation of Biodiesel-Biojet Achieved from Jatropha Curcas and Waste Cooking Oils over Chemically Modified Montmorillonite Clay. J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 340, 117175 10.1016/j.molliq.2021.117175. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B.; Wan C.; Kang X.; Chen M.; Zhang C.; Bai Y.; Dong L. Enhanced CO2 Separation of Mixed Matrix Membranes with ZIF-8@GO Composites as Fillers: Effect of Reaction Time of ZIF-8@GO. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2019, 223, 113–122. 10.1016/j.seppur.2019.04.063. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Negm N. A.; Sayed G. H.; Yehia F. Z.; Dimitry O. I. H.; Rabie A. M.; Azmy E. A. M. Production of Biodiesel Production from Castor Oil Using Modified Montmorillonite Clay. Egypt. J. Chem. 2016, 59, 1045–1060. 10.21608/ejchem.2016.1551. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kruk M.; Jaroniec M. Gas Adsorption Characterization of Ordered Organic–Inorganic Nanocomposite Materials. Chem. Mater. 2001, 13, 3169–3183. 10.1021/cm0101069. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.; Du Q.; Wang J.; Liu T.; Sun J.; Wang Y.; Wang Z.; Xia Y.; Xia L. Defluoridation from Aqueous Solution by Manganese Oxide Coated Graphene Oxide. J. Fluorine Chem. 2013, 148, 67–73. 10.1016/j.jfluchem.2013.01.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Al-qadri A. A. Q.; Drmosh Q. A.; Onaizi S. A. Case Studies in Chemical and Environmental Engineering Enhancement of Bisphenol a Removal from Wastewater via the Covalent Functionalization of Graphene Oxide with Short Amine Molecules. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2022, 6, 100233 10.1016/j.cscee.2022.100233. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H.; Hu Y. H. Effect of Oxygen Content on Structures of Graphite Oxides. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2011, 50, 6132–6137. 10.1021/ie102572q. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hosseinabadi-Farahani Z.; Hosseini-Monfared H.; Mahmoodi N. M. Graphene Oxide Nanosheet: Preparation and Dye Removal from Binary System Colored Wastewater. Desalin. Water Treat. 2015, 56, 2382–2394. 10.1080/19443994.2014.960462. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oveisi M.; Asli M. A.; Mahmoodi N. M. MIL-Ti Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) Nanomaterials as Superior Adsorbents: Synthesis and Ultrasound-Aided Dye Adsorption from Multicomponent Wastewater Systems. J. Hazard. Mater. 2018, 347, 123–140. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2017.12.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoodi N. M.; Oveisi M.; Panahdar A.; Hayati B.; Nasiri K. Synthesis of Porous Metal-Organic Framework Composite Adsorbents and Pollutant Removal from Multicomponent Systems. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2020, 243, 122572 10.1016/j.matchemphys.2019.122572. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haque E.; Jun J. W.; Jhung S. H. Adsorptive Removal of Methyl Orange and Methylene Blue from Aqueous Solution with a Metal-Organic Framework Material, Iron Terephthalate (MOF-235). J. Hazard. Mater. 2011, 185, 507–511. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2010.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badawi M. A.; Negm N. A.; Abou Kana M. T. H.; Hefni H. H.; Abdel Moneem M. M. Adsorption of Aluminum and Lead from Wastewater by Chitosan-Tannic Acid Modified Biopolymers: Isotherms, Kinetics, Thermodynamics and Process Mechanism. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 99, 465–476. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alghamdi A. A.; Al-Odayni A.-B.; Saeed W. S.; Al-Kahtani A.; Alharthi F. A.; Aouak T. Efficient Adsorption of Lead (II) from Aqueous Phase Solutions Using Polypyrrole-Based Activated Carbon. Materials 2019, 12, 2020. 10.3390/ma12122020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aksu Z. Application of Biosorption for the Removal of Organic Pollutants: A Review. Process Biochem. 2005, 40, 997–1026. 10.1016/j.procbio.2004.04.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoodi N. M.; Masrouri O.; Najafi F. Dye Removal Using Polymeric Adsorbent from Wastewater Containing Mixture of Two Dyes. Fibers Polym. 2014, 15, 1656–1668. 10.1007/s12221-014-1656-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Q.; Lu R.; Ren S.; Chen C.; Chen Z.; Yang X. Three Dimensional Reduced Graphene Oxide/ZIF-67 Aerogel: Effective Removal Cationic and Anionic Dyes from Water. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 348, 202–211. 10.1016/j.cej.2018.04.176. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Robati D.; Rajabi M.; Moradi O.; Najafi F.; Tyagi I.; Agarwal S.; Gupta V. K. Kinetics and Thermodynamics of Malachite Green Dye Adsorption from Aqueous Solutions on Graphene Oxide and Reduced Graphene Oxide. J. Mol. Liq. 2016, 214, 259–263. 10.1016/j.molliq.2015.12.073. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kannan N.; Sundaram M. M. Kinetics and Mechanism of Removal of Methylene Blue by Adsorption on Various Carbons—a Comparative Study. Dyes Pigm. 2001, 51, 25–40. 10.1016/S0143-7208(01)00056-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoodi N. M. Manganese Ferrite Nanoparticle: Synthesis, Characterization, and Photocatalytic Dye Degradation Ability. Desalin. Water Treat. 2015, 53, 84–90. 10.1080/19443994.2013.834519. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoodi N. M.; Najafi F. Synthesis, Amine Functionalization and Dye Removal Ability of Titania/Silica Nano-Hybrid. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2012, 156, 153–160. 10.1016/j.micromeso.2012.02.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoodi N. M.; Taghizadeh A.; Taghizadeh M.; Shahali Baglou M. A. Surface Modified Montmorillonite with Cationic Surfactants: Preparation, Characterization, and Dye Adsorption from Aqueous Solution. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 103243 10.1016/j.jece.2019.103243. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hayati B.; Mahmoodi N. M.; Maleki A. Dendrimer–Titania Nanocomposite: Synthesis and Dye-Removal Capacity. Res. Chem. Intermed. 2015, 41, 3743–3757. 10.1007/s11164-013-1486-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hasanzadeh M.; Simchi A.; Far H. S. Kinetics and Adsorptive Study of Organic Dye Removal Using Water-Stable Nanoscale Metal Organic Frameworks. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2019, 233, 267–275. 10.1016/j.matchemphys.2019.05.050. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Basiri Parsa J.; Hagh Negahdar S. Treatment of Wastewater Containing Acid Blue 92 Dye by Advanced Ozone-Based Oxidation Methods. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2012, 98, 315–320. 10.1016/j.seppur.2012.06.041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim S. M.; Badawy A. A.; Essawy H. A. Improvement of Dyes Removal from Aqueous Solution by Nanosized Cobalt Ferrite Treated with Humic Acid during Coprecipitation. J. Nanostructure Chem. 2019, 9, 281–298. 10.1007/s40097-019-00318-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoodi N. M. Dendrimer Functionalized Nanoarchitecture: Synthesis and Binary System Dye Removal. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2014, 45, 2008–2020. 10.1016/j.jtice.2013.12.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anwer K. E.; Farag A. A.; Mohamed E. A.; Azmy E. M.; Sayed G. H. Corrosion Inhibition Performance and Computational Studies of Pyridine and Pyran Derivatives for API X-65 Steel in 6M H2SO4. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2021, 523. 10.1016/j.jiec.2021.03.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abubshait H. A.; Farag A. A.; El-Raouf M. A.; Negm N. A.; Mohamed E. A. Graphene Oxide Modified Thiosemicarbazide Nanocomposite as an Effective Eliminator for Heavy Metal Ions. J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 327, 114790 10.1016/j.molliq.2020.114790. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Sabagh A. M.; Abdou M. I.; Migahed M. A.; Fadl A. M.; Farag A. A.; Mohammedy M. M.; Abd-Elwanees S.; Deiab A. Influence of Ilmenite Ore Particles as Pigment on the Anticorrosion and Mechanical Performance Properties of Polyamine Cured Epoxy for Internal Coating of Gas Transmission Pipelines. Egypt. J. Pet. 2018, 27, 427–436. 10.1016/j.ejpe.2017.07.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Farag A. A.; Mohamed E. A.; Sayed G. H.; Anwer K. E. Experimental/Computational Assessments of API Steel in 6 M H2SO4 Medium Containing Novel Pyridine Derivatives as Corrosion Inhibitors. J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 330. 10.1016/j.molliq.2021.115705. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Farag A. A. Oil-in-Water Emulsion of a Heterocyclic Adduct as a Novel Inhibitor of API X52 Steel Corrosion in Acidic Solution. Corros. Rev. 2018, 36, 575–588. 10.1515/corrrev-2018-0002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Farag A. A.; Badr E. A. Non-Ionic Surfactant Loaded on Gel Capsules to Protect Downhole Tubes from Produced Water in Acidizing Oil Wells. Corros. Rev. 2020, 38, 151–164. 10.1515/corrrev-2019-0030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vasile E.; Pandele A. M.; Andronescu C.; Selaru A.; Dinescu S.; Costache M.; Hanganu A.; Raicopol M. D.; Teodorescu M. Hema-Functionalized Graphene Oxide: A Versatile Nanofiller for Poly(Propylene Fumarate)-Based Hybrid Materials. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 18685. 10.1038/s41598-019-55081-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huong L. M.; Thinh D. B.; Tu T. H.; Dat N. M.; Hong T. T.; Cam P. T. N.; Trinh D. N.; Nam H. M.; Phong M. T.; Hieu N. H. Ice Segregation Induced Self-Assembly of Graphene Oxide into Graphene-Based Aerogel for Enhanced Adsorption of Heavy Metal Ions and Phenolic Compounds in Aqueous Media. Surf. Interfaces 2021, 26, 101309 10.1016/j.surfin.2021.101309. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar R.; Bhattacharya S.; Sharma P. Novel Insights into Adsorption of Heavy Metal Ions Using Magnetic Graphene Composites. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 106212 10.1016/j.jece.2021.106212. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y.; Wu L.; Deng H.; Qiao N.; Zhang D.; Lin H.; Chen Y. Modified Graphene Oxide Composite Aerogels for Enhanced Adsorption Behavior to Heavy Metal Ions. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 106008 10.1016/j.jece.2021.106008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hashem H. E.; Mohamed E. A.; Farag A. A.; Negm N. A.; Azmy E. A. M. New Heterocyclic Schiff Base-metal Complex: Synthesis, Characterization, Density Functional Theory Study, and Antimicrobial Evaluation. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2021, 35, e6322 10.1002/aoc.6322. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H.; Wang Y.; Zhang Y.; Niu Z.; Li X. Amino-Functionalized Graphene Oxide for Cr(VI), Cu(II), Pb(II) and Cd(II) Removal from Industrial Wastewater. Open Chem. 2020, 18, 97–107. 10.1515/chem-2020-0009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ma S.; Zhan S.; Jia Y.; Zhou Q. Highly Efficient Antibacterial and Pb(II) Removal Effects of Ag-CoFe2O4-GO Nanocomposite. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 10576–10586. 10.1021/acsami.5b02209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury T.; Zhang L.; Zhang J.; Aggarwal S. Pb(Ii) Adsorption from Aqueous Solution by an Aluminum-Based Metal Organic Framework-Graphene Oxide Nanocomposite. Mater. Adv. 2021, 2, 3051–3059. 10.1039/d1ma00046b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang R.; Fan X.; Li Y.-Z. Efficient Removal of a Low Concentration of Pb(II), Fe(III) and Cu(II) from Simulated Drinking Water by Co-Immobilization between Low-Dosages of Metal-Resistant/Adapted Fungus Penicillium Janthinillum and Graphene Oxide and Activated Carbon. Chemosphere 2022, 286, 131591 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.131591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S.; Lingamdinne L. P.; Yang J.-K.; Chang Y.-Y.; Koduru J. R. Potential Electromagnetic Column Treatment of Heavy Metal Contaminated Water Using Porous Gd2O3-Doped Graphene Oxide Nanocomposite: Characterization and Surface Interaction Mechanisms. J. Water Process Eng. 2021, 41, 102083 10.1016/j.jwpe.2021.102083. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khazaei M.; Nasseri S.; Ganjali M. R.; Khoobi M.; Nabizadeh R.; Mahvi A. H.; Nazmara S.; Gholibegloo E. Response Surface Modeling of Lead (II) Removal by Graphene Oxide-Fe3O4 Nanocomposite Using Central Composite Design. J. Environ. Heal. Sci. Eng. 2016, 14, 2. 10.1186/s40201-016-0243-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez C.; Tapia C.; Leiva-Aravena E.; Leiva E. Graphene Oxide-ZnO Nanocomposites for Removal of Aluminum and Copper Ions from Acid Mine Drainage Wastewater. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6911. 10.3390/ijerph17186911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Maghrab H. H.; Mikhail S. Removal of Heavy Metals via Adsorption Using Natural Clay Material Removal of Heavy Metals via Adsorption Using Natural Clay Material. J. Environ. Earth Sci. 2016, 4, 38–47. [Google Scholar]

- Yurtsever M.; Nalçak M. Al(III) Removal from Wastewater by Natural Clay and Coconut Shell. Glob. Nest J. 2019, 21, 477–483. 10.30955/gnj.002566. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abdel-Ghani N. T.; El-Chaghaby G. A.; Zahran E. M. Cost Effective Adsorption of Aluminium and Iron from Synthetic and Real Wastewater by Rice Hull Activated Carbon (RHAC). Am. J. Anal. Chem. 2015, 6, 71–83. 10.4236/ajac.2015.61007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mexent Z.; Zue Mve M.; Biboutou R.; Eba F.; Njopwouo D. Kinetic and Isotherm Studies of Al (III) Ions Removal from Aqueous Solution by Adsorption onto Coula Edulis Nut Shell Activated Carbon. J. Environ. Earth Sci. 2016, 6, 5. [Google Scholar]