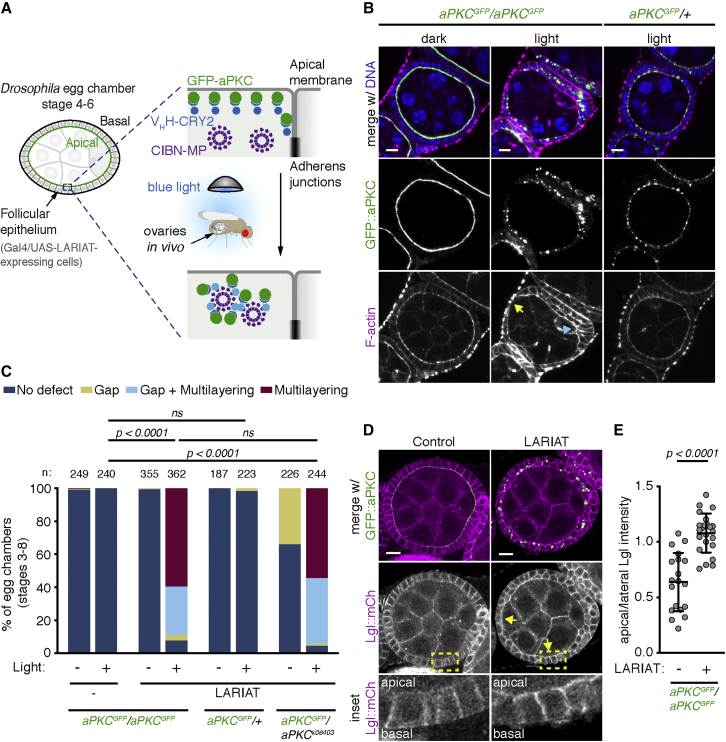

Figure 1.

Optogenetic clustering inactivates aPKC and disrupts tissue architecture in vivo

(A) Schematic representation of optogenetic aPKC inactivation strategy using LARIAT (VHH::CRY2 and CIBN::MP). GFP::aPKC is targeted by CRY2 fused with a GFP nanobody (VHH). Exposing flies to blue light triggers CRY2 binding to CIBN fused with a multimerization domain (MP).

(B) Living flies were exposed to blue light for 48 h to cluster GFP::aPKC or kept in the dark (control) before egg chambers were stained for F-actin and DNA. Flies were either homozygous or heterozygous for endogenously tagged GFP::aPKC. Arrows point to epithelial gap (yellow) and multilayering (cyan).

(C) Frequency of epithelial defects in egg chambers (stages 3–8) from flies with the indicated combinations of wild-type, GFP::aPKC, or apkck06403 null allele after 24 h blue-light exposure (n, number of egg chambers). LARIAT was expressed in the follicular epithelium when indicated. Control flies were kept in the dark. Fisher’s exact test compared the incidence of defects between different samples (ns, not significant).

(D) Midsagittal sections of control and LARIAT egg chambers from flies expressing GFP::aPKC and Lgl::mCherry exposed to blue light for 24 h. Arrows point to apical Lgl::mCherry. Yellow boxes define inset region.

(E) Ratio of apical/lateral mean pixel intensity of Lgl::mCherry in control (n = 684 cells, 19 egg chambers) and LARIAT (n = 447 cells, 23 egg chambers). Graphs show mean ± SD (unpaired t test); gray points represent average for individual egg chambers. Scale bars, 10 μm.

See also Figure S1.