Abstract

Background:

Disability in patients with medically refractory ulcerative colitis (UC) after total proctocolectomy (TPC) with ileal pouch anal anastomosis (IPAA) is not well understood. The aim of this study was to compare disability in patients with IPAA vs medically managed UC, and identify predictors of disability.

Methods:

This was a multi-center cross-sectional study performed at five academic institutions in New York City. Patients with medically or surgically treated UC were recruited. Clinical and socioeconomic data were collected and the inflammatory bowel disease disability index (IBD-DI) was administered to eligible patients. Predictors of moderate-severe disability (IBD-DI≥35) were assessed in univariable and multivariable models.

Results:

A total of 94 patients with IPAA and 128 patients with medically managed UC completed the IBD-DI. Among patients with IPAA and UC, 35 (37.2%) and 30 (23.4%) had moderate-severe disability, respectively. Patients with IPAA had significantly greater IBD-DI scores compared to patients with medically managed UC (29.8 vs 17.9, p<0.001). When stratified by disease activity, patients with active IPAA disease had significantly greater median IBD-DI scores compared to patients with active UC (44.2 vs 30.4, p=0.01), and patients with inactive IPAA disease had significantly greater median IBD-DI scores compared to patients with inactive UC (23.1 vs 12.5, p<0.001). Moderate-severe disability in patients with IPAA was associated with female sex, active disease, and public insurance.

Conclusion:

Patients with IPAA have higher disability scores than patients with UC, even after adjustment for disease activity. Female sex and public insurance are predictive of significant disability in patients with IPAA.

Keywords: disability, pouch, ulcerative colitis

Introduction

Approximately 10–15% of patients with ulcerative colitis (UC) require total proctocolectomy (TPC) with ileal pouch anal anastomosis (IPAA) for medically refractory disease or dysplasia.1 Most commonly performed in two or three stages, TPC with IPAA involves restoration of intestinal continuity and offers patients an alternative to a permanent end ileostomy. Unfortunately, leakage and incontinence can occur in patients after TPC with IPAA, and pouch inflammation is common with cumulative incidence rates of 50% at two years.2, 3 Symptoms of pouch inflammation such as frequency, urgency, and pain have been associated with depression, fatigue and decreased quality of life.4

Disability, defined as any restriction of normal activity as measured by the validated inflammatory bowel disease disability index (IBD-DI), is now recognized as a major, long-term outcome of IBD.5–7 Crohn’s disease and UC are associated with similar disease burden, and the treatment goal for both is the reduction of disability and optimization of quality of life.8 While medically managed, active UC is associated with significant disability, less is known about surgically managed UC after TPC with IPAA.9, 10 Van Gennep et al reported higher bowel movement frequency and more perianal skin irritation in Belgian patients with IPAA, however no difference in disability scores was noted when compared to patients with UC managed with anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) therapy.11 In contrast, Lee et al reported lower disability scores in Australian patients with IPAA compared to those with medically managed UC.12 We have also previously shown that disability in patients with IBD is influenced by race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic factors independent of disease activity in the United States (US).13

Given the current conflicting data and the growing importance of disability as a long-term outcome in IBD, the aim of this study was to assess the level of disability in patients with IPAA vs medically managed UC, and identify predictors of disability in a diverse US patient population.

Methods

This was a multi-center, cross-sectional study performed at five academic institutions in New York City through the New York Crohn’s and Colitis Organization (NYCCO). Adult patients 18–75 years of age with either medically refractory UC status post TPC with IPAA or medically managed UC were identified and consecutively recruited between July 2017 and September 2020 during routine clinic appointments. Patients with IBD-unclassified, IPAA creation within the last 12 months, and major psychiatric illness were excluded.

Clinical, demographic and socioeconomic data were collected by patient self-report and confirmed by medical chart review. Clinical disease activity in patients with IPAA at the time of study participation was defined using the clinical sub-score of the Pouchitis Disease Activity Index (PDAI), a four-point questionnaire with a maximum score of six that includes stool frequency, rectal bleeding, fecal urgency/abdominal cramps, and fever.14 For the purpose of this study, inactive disease was considered a clinical PDAI sub-score of zero, and active disease was any clinical sub-score greater than or equal to one. Clinical disease activity in patients with medically managed UC at the time of study participation was defined according to the partial Mayo score, a nine point score with disease severity delineated by the following thresholds: inactive 0–1, mild 2–4, moderate 5–6, and severe 7–9.15 A healthcare provider administered the IBD-DI, a validated questionnaire consisting of 14 questions pertaining to perceived overall health, sleep and energy, regulation of defecation, interpersonal activities, work and education, and symptoms of diarrhea and arthralgia (Supplemental Table). The IBD-DI score is computed on a scale of 0–100. Scores less than or equal to 35 indicate no disability or mild disability, while scores greater than 35 indicate moderate-to-severe disability.6

The primary objective was to report the level of disability in patients with IPAA in comparison to patients with medically managed UC (herein designated as UC) as reported by the IBD-DI. The secondary objective was to identify predictors of disability in patients with IPAA. Nonparametric continuous variables were reported as median (interquartile range, IQR) and categorical variables were reported as frequencies (%). Associations between independent variables and the IBD-DI were analyzed using chi-squared and Fisher’s exact tests for categorical comparisons and Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous variable comparisons. Variables that were associated with the IBD-DI with p < 0.10 on univariable analysis were tested in multivariable models using logistic regression. Adjusted odds ratios (aOR) are reported with 95% confidence intervals (CI). P values ≤0.05 were considered significant for all analyses. All analysis was performed in R version 1.2.5042.

Results

A total of 94 patients with IPAA and 128 patients with UC completed the IBD-DI. Patient demographics and disease characteristics are given in Table 1. The median age of patients was 38.0 [28.4–54.0] years, and median disease duration was 10.0 [5.0–20.0] years. Patients with IPAA had a median pouch duration of 7.4 [IQR 2.6–16.7] years and significantly longer disease duration than patients with UC (15.0 vs 7.0 years, p<0.001). There were significantly more white (87.2% vs 68.0%) and less Black (7.5% vs 14.8%) and Asian (4.3% vs 8.6%) patients with IPAA compared to those with UC (p=0.006). There were significantly more patients with UC compared to patients with IPAA using public insurance (38.3% vs 25.5%, p=0.006). Other baseline demographics, including co-morbidities and extraintestinal manifestations, were comparable between the two groups. Compared to patients with medically managed UC, patients with IPAA had significantly greater exposure to immunomodulators, steroids, and anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) agents before colectomy, and significantly less exposure to mesalamine, immunomodulators, anti-TNF agents, and anti-integrin agents after IPAA. Full medication details are provided in Table 2.

Table 1.

Patient demographics and clinical characteristics

| UC N=128 (%) | IPAA N=94 (%) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age* | 36.5 [27.8, 53.3] | 41.0 [31.0, 55.5] | 0.16 |

| Sex | |||

| ● Male | 59 (46.1) | 35 (37.2) | 0.24 |

| ● Female | 69 (53.9) | 59 (62.8) | |

| Race | 0.006 | ||

| ● White | 87 (68.0) | 82 (87.2) | |

| ● Black | 19 (14.8) | 8 (7.5) | |

| ● Asian | 11 (8.6) | 4 (4.3) | |

| ● Mixed/Other Race | 11 (8.6) | 1 (1.1) | |

| Extraintestinal Manifestations | 43 (33.5) | 21 (22.3) | 0.07 |

| Medical co-morbidities | 70 (54.7) | 45 (47.9) | 0.43 |

| Marital Status | |||

| ● Single | 69 (53.9) | 43 (45.7) | 0.29 |

| ● Married | 59 (46.1) | 51 (54.3) | |

| Education Status | |||

| ● Did not complete high school | 5 (4.0) | 2 (2.1) | 0.31 |

| ● High school diploma or GED | 26 (20.6) | 15 (16.0) | |

| ● College degree or equivalent | 62 (49.2) | 42 (44.7) | |

| ● Professional degree | 33 (26.2) | 35 (37.2) | |

| Annual Income | |||

| ● ≤$99,999 | 63 (49.2) | 44 (46.8) | 0.71 |

| ● >100,000 | 58 (47.9) | 45 (52.9) | |

| Employment Status | |||

| ● Student | 13 (10.2) | 5 (5.3) | 0.21 |

| ● Unemployed | 17 (13.3) | 17 (18.1) | |

| ● Retired | 10 (7.8) | 13 (13.8) | |

| ● Employed | 88 (68.8) | 59 (62.8) | |

| Social Security Benefits | |||

| ● Yes | 22 (17.3) | 22 (23.4) | 0.34 |

| ● No | 105 (82.7) | 72 (76.6) | |

| Insurance Status | |||

| ● Public | 49 (38.3) | 24 (25.5) | 0.006 |

| ● Private | 77 (61.1) | 69 (74.2) | |

| Disease Duration* | 7.0 [3.0, 13.0] | 15.0 [8.0, 26.0] | <0.001 |

Median [Quartile 1, Quartile 3]

Table 2.

Medication use in patients with UC vs IPAA

| Medication Class | UC N=128 (%) | IPAA N=94 (%) | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| UC | PRE-STC | POST-IPAA | * | ** | |

| None | 6 (4.7) | 0 (0) | 40 (43.0) | .08 | <.001 |

|

| |||||

| Mesalamine | 68 (53.1) | 52 (61.2) | 6 (6.5) | .31 | <.001 |

|

| |||||

| Immunomodulators | 21 (16.4) | 27 (31.8) | 3 (3.2) | .01 | .002 |

|

| |||||

| Steroids | 28 (21.9) | 45 (52.9) | 13 (14.0) | <.001 | .19 |

|

| |||||

| Antibiotics | - | 12 (14.1) | 11 (12.9) | - | - |

|

| |||||

| Biologics | |||||

| Anti-TNFs | 45 (35.2) | 47 (55.3) | 15 (16.1) | .01 | .003 |

| Anti-integrin | 22 (17.2) | 15 (17.6) | 5 (5.4) | 1.0 | .01 |

| Anti-interleukin | 1 (0.8) | 0 (0) | 13 (14.0) | 1.0 | <.001 |

P value between UC and IPAA pre subtotal colectomy (STC)

P-value between UC and post-IPAA at the time of IBD-DI

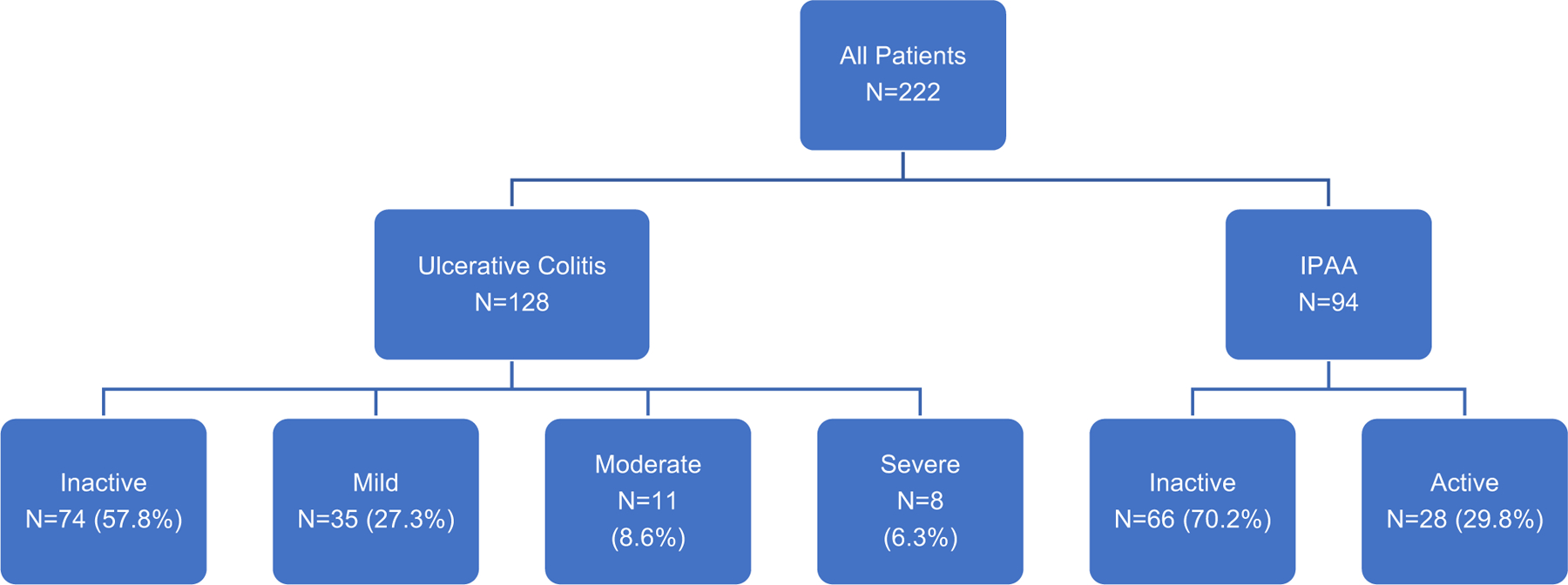

At the time of IBD-DI administration, clinical disease activity among patients with UC was classified as inactive in 74 (57.8%) patients, mild in 35 (27.3%), moderate in 11 (8.6%), and severe in 8 (6.3%) (Figure 1). Clinical disease activity among patients with IPAA was classified as inactive in 66 (70.2%) patients and active in 28 (29.8%). Among patients with IPAA, 30 (39.0%) had a prior history of acute pouchitis, 47 (61.0%) of chronic pouchitis, and 24 (27.9%) of cuffitis.

Figure 1.

Clinical disease activity among patients

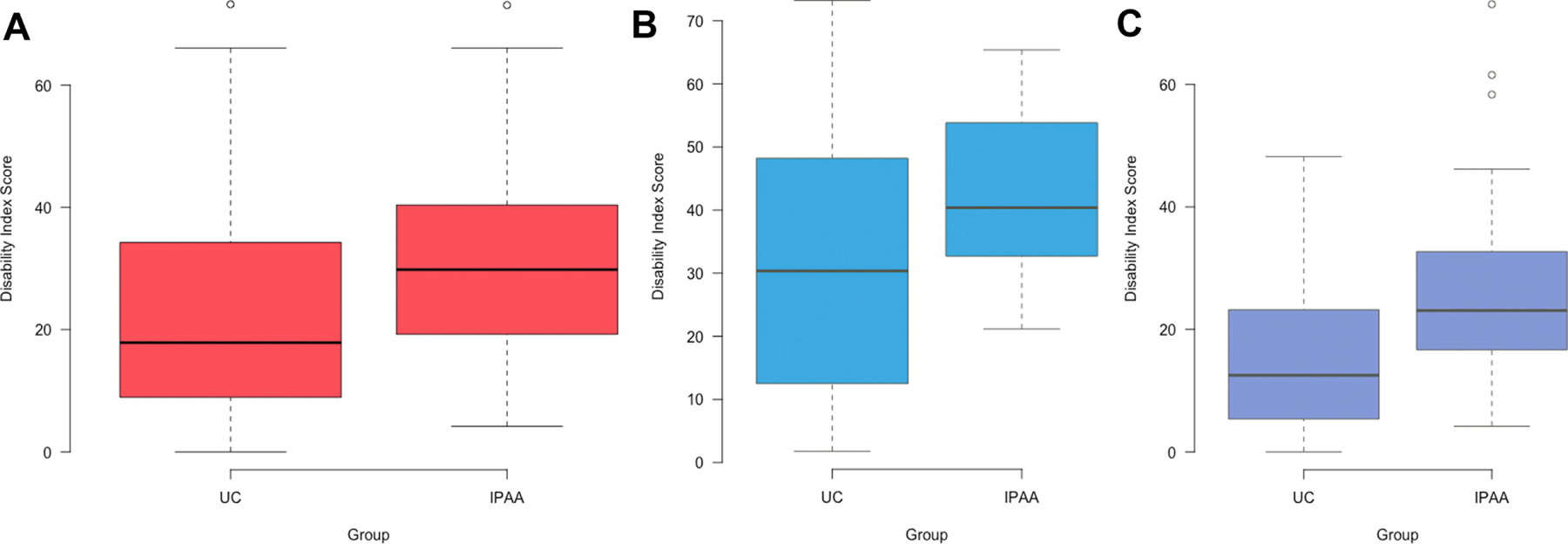

The median IBD-DI score for all patients was 23.1 [IQR 12.5–37.3] and 65 (29.2%) patients overall had an IBD-DI score > 35 indicating moderate-severe disability. Thirty-five (37.2%) patients with IPAA and 30 (23.4%) patients with UC had an IBD-DI score > 35 that indicated moderate-severe disability. Patients with IPAA had significantly greater median IBD-DI scores compared to patients with medically managed UC (29.8 vs 17.9, p<0.001) (Figure 2a). When stratified by IBD-DI topic, patients with IPAA had greater median disability scores in the fields of overall health, sleep and energy, regulating defecation and pain. The breakdown of the IBD-DI score by topic for patients with UC and patients with IPAA is presented in Table 3. When stratified by clinical disease activity, patients with active IPAA disease had significantly greater median IBD-DI scores compared to patients with active UC (44.2 vs 30.4, p=0.01) (Figure 2b), and patients with inactive IPAA disease had significantly greater median IBD-DI scores compared to patients with inactive UC (23.1 vs 12.5, p<0.001) (Figure 2c). In a subset analysis in which physician global assessment was removed from the partial mayo score and only symptom scores were compared among patients with UC and IPAA, patients with IPAA had significantly greater median IBD-DI scores regardless of disease activity (40.4 vs 28.6, p=0.02 in active disease and 23.1 vs 13.4, p<0.001 in inactive disease). In patients with IPAA, there was no significant difference in median IBD-DI scores among those with and without chronic pouchitis (30.8 vs 26.0, p=0.61).

Figure 2.

IBD-DI scores stratified by disease activity. (2a) All patients. (2b) Patients with active disease. (2c) Patients with inactive disease.

Table 3.

Median IBD-DI sub-score comparison in patients with UC vs IPAA

| Sub Section of IBD-DI | UC N=128 | Pouch N=94 | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Health | 1.0 [0 – 2] | 1.0 [1.0 – 2.0] | .01 |

| Sleep and Energy | 1.25 [.5 – 2.0] | 1.5 [1.0 – 2.5] | .01 |

| Affect | .75 [0 – 1.5] | 1.0 [0 – 2.0] | .24 |

| Body Image | 0 [0 – 1.0] | 0 [0 – 1.0] | .28 |

| Pain | .5 [0 – 2.0] | 1.0 [0 – 2.0] | .03 |

| Regulating Defecation | 0 [0 – 1.0] | 1.0 [0 – 2.0] | <.001 |

| Looking after one’s health | 0 [0 – 1.0] | 1.0 [0 – 2.0] | .21 |

| Interpersonal Activities | 0 [0 – 1.0] | 0 [0 – 1.0] | .72 |

| Work and Education | 0 [0 – 1.0] | 2.5 [0 – 1.0] | .48 |

On multivariable analysis, female patients with IPAA were more likely to report moderate-severe disability compared to male patients (aOR 4.74 95% CI 1.1–26.9). Patients with active symptoms (aOR 26.3 95% CI 5.4–190) and public insurance (aOR 25.3 95% CI 4.0–232) had greater odds of moderate-severe disability. Age, race, and annual income were not significantly associated with disability. Full multivariable results are detailed in Table 4.

Table 4.

Predictors of moderate-severe disability in patients with IPAA on multivariable analysis

| Covariable | aOR (95% CI) | p value |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.96 (0.9–1.0) | .09 |

| Female sex (reference male) | 4.74 (1.1–26.9) | .05 |

| Black race (reference white) | 10.3 (0.4–5.4) | .20 |

| Asian race (reference white) | 0.11 (0.01–4.1) | .20 |

| Annual income >$100,000 (reference ≤$99,999) | 4.00 (0.89–23.5) | .09 |

| Active disease (reference inactive) | 26.3 (5.4–190) | <.0001 |

| Public insurance (reference private) | 25.3 (4.0–232) | .002 |

Discussion

In this cross-sectional, multicenter study assessing disability among patients with IPAA vs medically managed UC, approximately 30% had moderate-severe disability. Patients with active and inactive IPAA disease had significantly greater disability scores than patients with active and inactive medically managed UC. Female sex, active disease and public insurance were significantly associated with disability in patients with IPAA.

Although TPC with IPAA is the gold standard surgery for patients with medically refractory UC, it is not without its complications. Our study is the first in the US to use the validated IBD-DI in a diverse population to specifically assess the level of disability in patients with IPAA in comparison to patients with medically managed UC. Unlike previous studies which did not report a significant difference in IBD-DI scores in patients with IPAA compared to patients with medically managed UC, our study noted higher disability scores in patients with active and inactive IPAA disease, specifically in the fields of overall health, sleep and energy, regulating defecation, and pain. These higher scores, particularly in patients with active disease, are likely driven by such postoperative pouch complications as fecal incontinence, nocturnal seepage, frequency, urgency and pouchitis that significantly impact quality of life.16 In addition, while we excluded patients with major psychiatric illness, anxiety and depression are common in patients with IPAA who are experiencing active disease and may contribute to higher disability.17

The impact of sex on IBD associated outcomes is well documented. Female patients have been shown to have higher rates of long-term complications after TPC such as bowel obstruction and fistula, and poor functional outcomes secondary to increased frequency, urgency, seepage and pad usage.18 In addition, female patients with IPAA have reported significantly lower mental health scores and energy levels compared to male patients over long-term follow-up.18 Indeed, our study corroborates the greater toll TPC with IPAA seems to have on female patients, with greater IBD-DI scores reported by female compared to male patients.

Moderate-severe disability in patients with IPAA was also associated with public insurance. This is consistent with that previously reported by our group in a larger population of patients with UC and CD, and speaks to the impact of socioeconomic status on disability.13 Patients who use public insurance are often subject to disparities in access to care and related adverse outcomes in chronic diseases, in addition to worse quality of life and fragmented care in those with IBD.19–22 Limited social resources and support, known to be an issue in patients with IBD, likely further compound disability in patients with IPAA who use public insurance.23 Social determinants of health should be considered in the care of patients with IBD, and particularly those with IPAA, to decrease disability and improve quality of life.

Our study had several strengths. The IBD-DI is a validated questionnaire with high internal consistency and interobserver validity, and an excellent method to objectively measure disability.6 Our sampled patient population was diverse and recruited from multiple centers in New York City, allowing for the generalizability of our findings within the United States. Disease activity, a known factor associated with disability, was controlled for in the analysis. Our study also had a number of limitations. First, we did not include endoscopic or biomarker disease indices. Subjective and objective measures of disease may not correlate in patients with IBD, and furthermore, the clinical sub-score of the PDAI may not correlate with its endoscopic and histologic sub-scores raising concern it does not adequately identify patients with active disease. 24 Second, this was a cross-sectional study and we were not able to report the change in disability over time. While our study reports significant disability in patients with IPAA, this might still be lower than their disability before TPC. The repeated assessment of disability using IBD-DI is important to consider for future longitudinal studies since it would allow for direct comparison of disability before and after TPC with IPAA. Third, the use of a questionnaire to assess disability introduces the risk of response bias, particularly because of the use of a response scale which can predispose to extreme answers. Despite this, the risk of response bias is low in our study given the lack of sensitive questions involved and the use of the medical record to confirm clinical data. Fourth, the IBD-DI does not include as assessment of sexual health, which may be significantly different in patients with UC compared to patients with IPAA related to the surgical risk of sexual dysfunction. 25, 26 Fifth, there is risk of selection bias as patients with active IPAA and UC disease may be more likely to present for follow-up and be surveyed compared to patients with inactive disease. To adjust for the impact of disease on predictors of disability, disease activity was controlled for in the multivariable model. Finally, while our sampled patient population was diverse and reflected the patient population in New York City, there were significant differences in race, insurance and disease duration among patients with UC and IPAA, potentially influencing IBD-DI scores and their comparison.

TPC with IPAA remains the best surgical option for patients with medically refractory UC, however its impact on disability, even in patients with inactive disease, may be underestimated. While the PDAI is a validated measure of pouch activity, it is imperfect due to its lack of context with respect to the patient’s overall wellbeing. The IBD-DI should be incorporated into post-IPAA outcome measures, and patients should be followed closely for medical optimization to minimize symptoms and disability. Special attention should be paid to such socioeconomic factors that could impact disability perception and referral to licensed clinical social workers experienced in resource identification and allocation should be prioritized.

Supplementary Material

What You Need to Know.

Background:

The aim of this study was to compare disability in patients with ileal pouch anal anastomosis (IPAA) vs medically managed ulcerative colitis (UC), and identify predictors of disability.

Findings:

Patients with IPAA have higher disability scores than patients with UC, even after adjustment for disease activity. Moderate-severe disability in patients with IPAA is associated with female sex and public insurance.

Implications for patient care:

IPAA is the best surgical option for patients with medically refractory UC, however its impact on disability may be underestimated. Patients should benefit from social support to minimize disability after IPAA.

Grant Support

The authors declare no funding support for this project.

Disclosures

RCU is supported by an NIH K23 Career Development Award (K23KD111995-01A1). JEA is supported by a career development award from the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation. JFC reports receiving research grants from AbbVie, Janssen Pharmaceuticals and Takeda; receiving payment for lectures from AbbVie, Amgen, Allergan, Inc. Ferring Pharmaceuticals, Shire, and Takeda; receiving consulting fees from AbbVie, Amgen, Arena Pharmaceuticals, Boehringer Ingelheim, BMS, Celgene Corporation, Eli Lilly, Ferring Pharmaceuticals, Galmed Research, Genentech, Galxo Smith Kline, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Kaleido Biosciences, Imedex, Immunic, Iterative Scopes, Merck, Microba, Novartis, PBM Capital, Pfizer, Sanofi,Takeda, TiGenix, Vifor; and hold stock options in Intestinal Biotech Development. The authors have no other relevant disclosures.

Abbreviations

- TPC

total proctocolectomy

- IPAA

ileal pouch anal anastomosis

- IBD

inflammatory bowel disease

- CD

Crohn’s disease

- UC

ulcerative colitis

- DI

Disability Index

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Fumery M, Singh S, Dulai PS, et al. Natural History of Adult Ulcerative Colitis in Population-based Cohorts: A Systematic Review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018; 16: 343–356.e343. 2017/06/20. DOI: 10.1016/j.cgh.2017.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barnes EL, Herfarth HH, Kappelman MD, et al. Incidence, Risk Factors, and Outcomes of Pouchitis and Pouch-Related Complications in Patients With Ulcerative Colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020. 2020/06/26. DOI: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.06.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kayal M, Plietz M, Rizvi A, et al. Inflammatory Pouch Conditions Are Common After Ileal Pouch Anal Anastomosis in Ulcerative Colitis Patients. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2020; 26: 1079–1086. 2019/10/07. DOI: 10.1093/ibd/izz227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barnes EL, Herfarth HH, Sandler RS, et al. Pouch-Related Symptoms and Quality of Life in Patients with Ileal Pouch-Anal Anastomosis. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2017; 23: 1218–1224. 2017/04/21. DOI: 10.1097/mib.0000000000001119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lo B, Prosberg MV, Gluud LL, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis: assessment of factors affecting disability in inflammatory bowel disease and the reliability of the inflammatory bowel disease disability index. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2018; 47: 6–15. 2017/10/11. DOI: 10.1111/apt.14373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gower-Rousseau C, Sarter H, Savoye G, et al. Validation of the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Disability Index in a population-based cohort. Gut 2017; 66: 588–596. 2015/12/10. DOI: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-310151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Le Berre C SW, Colombel JF, et al. Selecting Endpoints for Disease-Modification Trials in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: the SPIRIT consensus from the IOIBD. Gastroenterology 2020; Accepted. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Le Berre C, Ananthakrishnan AN, Danese S, et al. Ulcerative Colitis and Crohn’s Disease Have Similar Burden and Goals for Treatment. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020; 18: 14–23. 2019/07/14. DOI: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Siebert U, Wurm J, Gothe RM, et al. Predictors of temporary and permanent work disability in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: results of the swiss inflammatory bowel disease cohort study. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2013; 19: 847–855. 2013/03/01. DOI: 10.1097/MIB.0b013e31827f278e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Høivik ML, Moum B, Solberg IC, et al. Work disability in inflammatory bowel disease patients 10 years after disease onset: results from the IBSEN Study. Gut 2013; 62: 368–375. 2012/06/22. DOI: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Gennep S, Sahami S, Buskens CJ, et al. Comparison of health-related quality of life and disability in ulcerative colitis patients following restorative proctocolectomy with ileal pouch-anal anastomosis versus anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017; 29: 338–344. 2016/12/03. DOI: 10.1097/meg.0000000000000798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee Y, McCombie A, Gearry R, et al. Disability in Restorative Proctocolectomy Recipients Measured using the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Disability Index. J Crohns Colitis 2016; 10: 1378–1384. 2016/06/11. DOI: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjw114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Agrawal M, Cohen-Mekelburg S, Kayal M, et al. Disability in inflammatory bowel disease patients is associated with race, ethnicity and socio-economic factors. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2019; 49: 564–571. 2019/01/22. DOI: 10.1111/apt.15107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sandborn WJ, Tremaine WJ, Batts KP, et al. Pouchitis after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis: a Pouchitis Disease Activity Index. Mayo Clin Proc 1994; 69: 409–415. 1994/05/01. DOI: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)61634-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lewis JD, Chuai S, Nessel L, et al. Use of the noninvasive components of the Mayo score to assess clinical response in ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2008; 14: 1660–1666. 2008/07/16. DOI: 10.1002/ibd.20520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peyrin-Biroulet L, Germain A, Patel AS, et al. Systematic review: outcomes and post-operative complications following colectomy for ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2016; 44: 807–816. 2016/08/19. DOI: 10.1111/apt.13763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gorrepati VS, Yadav S, Stuart A, et al. Anxiety, depression, and inflammation after restorative proctocolectomy. Int J Colorectal Dis 2018; 33: 1601–1606. 2018/07/01. DOI: 10.1007/s00384-018-3110-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rottoli M, Remzi FH, Shen B, et al. Gender of the patient may influence perioperative and long-term complications after restorative proctocolectomy. Colorectal Dis 2012; 14: 336–341. 2011/06/22. DOI: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2011.02634.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wong RJ, Jain MK, Therapondos G, et al. Race/ethnicity and insurance status disparities in access to direct acting antivirals for hepatitis C virus treatment. Am J Gastroenterol 2018; 113: 1329–1338. 2018/03/11. DOI: 10.1038/s41395-018-0033-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shin JY, Yoon JK, Shin AK, et al. Association of Insurance and Community-Level Socioeconomic Status With Treatment and Outcome of Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Pharynx. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2017; 143: 899–907. 2017/07/01. DOI: 10.1001/jamaoto.2017.0837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rubin GP, Hungin AP, Chinn DJ, et al. Quality of life in patients with established inflammatory bowel disease: a UK general practice survey. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2004; 19: 529–535. 2004/02/28. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.1873.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cohen-Mekelburg S, Rosenblatt R, Gold S, et al. Fragmented Care is Prevalent Among Inflammatory Bowel Disease Readmissions and is Associated With Worse Outcomes. Am J Gastroenterol 2019; 114: 276–290. 2018/11/14. DOI: 10.1038/s41395-018-0417-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nguyen NH, Khera R, Ohno-Machado L, et al. Estimates of the Prevalence and Effects of Food Insecurity and Social Support on Financial Toxicity in and Healthcare Use by Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020. 2020/06/12. DOI: 10.1016/j.cgh.2020.05.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ben-Bassat O, Tyler AD, Xu W, et al. Ileal pouch symptoms do not correlate with inflammation of the pouch. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014; 12: 831–837.e832. 2013/10/01. DOI: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Counihan TC, Roberts PL, Schoetz DJ Jr., et al. Fertility and sexual and gynecologic function after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. Dis Colon Rectum 1994; 37: 1126–1129. 1994/11/01. DOI: 10.1007/bf02049815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hueting WE, Gooszen HG and van Laarhoven CJ. Sexual function and continence after ileo pouch anal anastomosis: a comparison between a meta-analysis and a questionnaire survey. Int J Colorectal Dis 2004; 19: 215–218. 2003/10/18. DOI: 10.1007/s00384-003-0543-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.