Background:

A novel risk calculator based on clinical characteristics and noninvasive tests that predicts the onset of clinical sustained ventricular arrhythmias (VA) in patients with arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC) has been proposed and validated by recent studies. It remains unknown whether programmed ventricular stimulation (PVS) provides additional prognostic value.

Methods:

All patients with a definite ARVC diagnosis, no history of sustained VAs at diagnosis, and PVS performed at baseline were extracted from 6 international ARVC registries. The calculator-predicted risk for sustained VA (sustained or implantable cardioverter defibrillator treated ventricular tachycardia [VT] or fibrillation, [aborted] sudden cardiac arrest) was assessed in all patients. Independent and combined performance of the risk calculator and PVS on sustained VA were assessed during a 5-year follow-up period.

Results:

Two hundred eighty-eight patients (41.0±14.5 years, 55.9% male, right ventricular ejection fraction 42.5±11.1%) were enrolled. At PVS, 137 (47.6%) patients had inducible ventricular tachycardia. During a median of 5.31 [2.89–10.17] years of follow-up, 83 (60.6%) patients with a positive PVS and 37 (24.5%) with a negative PVS experienced sustained VA (P<0.001). Inducible ventricular tachycardia predicted clinical sustained VA during the 5-year follow-up and remained an independent predictor after accounting for the calculator-predicted risk (HR, 2.52 [1.58–4.02]; P<0.001). Compared with ARVC risk calculator predictions in isolation (C-statistic 0.72), addition of PVS inducibility showed improved prediction of VA events (C-statistic 0.75; log-likelihood ratio for nested models, P<0.001). PVS inducibility had a 76% [67–84] sensitivity and 68% [61–74] specificity, corresponding to log-likelihood ratios of 2.3 and 0.36 for inducible (likelihood ratio+) and noninducible (likelihood ratio–) patients, respectively. In patients with a ARVC risk calculator–predicted risk of clinical VA events <25% during 5 years (ie, low/intermediate subgroup), PVS had a 92.6% negative predictive value.

Conclusions:

PVS significantly improved risk stratification above and beyond the calculator-predicted risk of VA in a primary prevention cohort of patients with ARVC, mainly for patients considered to be at low and intermediate risk by the clinical risk calculator.

Keywords: arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy; electrophysiological techniques, cardiac; defibrillator, implantable; risk assessment; sudden cardiac death

Clinical Perspective.

What Is New?

In a multinational cohort of primary prevention patients with arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy, programmed ventricular stimulation was shown to predict incident sustained ventricular arrhythmia.

Programmed ventricular stimulation improves discrimination over the noninvasive published risk calculator for sustained ventricular arrhythmia in arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (https://www.ARVCrisk.com).

What Are the Clinical Implications?

Using programmed ventricular stimulation can improve risk prediction of sustained ventricular arrhythmia in arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy in the primary prevention setting, particularly among those with low or intermediate predicted risk on the basis of the noninvasive risk calculator.

If negative, its high negative predictive value (93%) in low and intermediate risk patients may support the decision to forgo implantable cardioverter defibrillator use in some patients.

Programmed ventricular stimulation results can be applied to the noninvasive arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy risk calculator (https://www.ARVCrisk.com) in a 2-step approach to facilitate personalized decision-making for implantable cardioverter defibrillator use.

Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC) is a cardiomyopathy characterized by progressive cardiomyocyte loss and fibro-fatty replacement.1 Patients with ARVC are at risk for life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias (VA) and sudden cardiac death (SCD), which may even represent the first clinical manifestation of the disease.1,2

The placement of an implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) is a crucial component of ARVC management.2,3 Nonetheless, arrhythmic risk stratification and the selection of the optimal candidates for ICD placement, especially for primary prevention of SCD, have proven difficult.4 A VA risk calculator in patients without previous sustained VAs has recently been proposed.5 This risk calculator included 7 clinical variables derived from noninvasive tests that are routinely performed in patients with ARVC. Its utility has been replicated in independent cohorts, and it has been shown to perform better than risk stratification algorithms currently proposed by consensus statements.6–12 Since its publication, the possibility of integrating additional parameters such as ventricular tachycardia (VT) inducibility on programmed ventricular stimulation (PVS) with the risk calculator has been suggested.13

The role of PVS for arrhythmic risk stratification in primary prevention ARVC has been debated. Although some studies supported its role as a predictor of sustained VA,14–19 others have reported a poor positive predictive value.20 Currently available studies, however, had a relatively limited sample size and often grouped together primary and secondary prevention patients with ARVC. This study aimed to investigate, in a large multicenter cohort of patients with ARVC, whether PVS has prognostic value independent of the existing ARVC VA risk calculator to further improve primary prevention arrhythmic risk stratification.

Methods

Patient Population

We conducted an observational, retrospective, multicenter cohort study.

The study population was extracted from 6 ARVC registries at academic institutions in 7 countries across North America and Europe. From each registry, all patients who met the following inclusion criteria were included in the present study: (1) diagnosed with definite ARVC as per the 2010 Task Force Criteria;21 (2) absence of spontaneous sustained VA or aborted SCD at disease diagnosis; and (3) performance of a PVS within 1 year before to 1 year after disease diagnosis, and before any sustained VA or SCD event.

The study was conducted in accordance to the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by local ethics and institutional review boards, and consent was obtained in accordance with national requirements. To maintain patient confidentiality, data and study materials will not be made available to other researchers for purposes of replicating the results. A limited dataset may be made available on request.

Variables and Outcomes Definition

For each patient, baseline demographic variables, data from ECG, echocardiography, cardiac magnetic resonance, and all 7 variables (age, sex, syncope of clear cardiac origin, number of leads with T wave inversion on a 12-lead ECG [sum of anterior and inferior leads], nonsustained ventricular tachycardia [NSVT], 24-hour premature ventricular complex count, and right ventricular ejection fraction [RVEF]) included in the ARVC risk calculator (https://www.ARVCrisk.com) were collected independently by each registry, in accordance with standard operating procedures and definitions previously presented.5 All genetic variants reported were adjudicated according to the 2015 American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics guidelines.22

PVS data were collected by study report, direct tracing, or medical record review. For each study, data about the stimulation protocol, the cycle length, and the morphology of all different VAs induced during PVS, and the baseline conduction measurements (atrio-hisian and His-ventricular time), were collected. A positive PVS was defined as the induction of a sustained monomorphic VT lasting ≥30 s or leading to hemodynamic compromise. Induction of polymorphic VT and ventricular fibrillation/flutter was not considered a positive PVS. Patients were accordingly classified into inducible (PVS+) and a noninducible (PVS–) groups.

Sustained VA was defined as a composite of SCD, sustained VT (lasting ≥30 s or with hemodynamic compromise or requiring cardioversion), ventricular fibrillation/flutter, or appropriate ICD intervention as reported previously.5 Rapid VA/(aborted) SCD was defined as sustained VT ≥250 bpm (cycle length ≤240 ms), ventricular fibrillation/flutter, SCD, or aborted SCD.5 Sustained VA was assessed using a combination of the ECG tracings, Holter ECG results, ICD interrogations, and clinical reports available at follow-up, as collected per each registry practice.

The primary outcome of the study was the comparison of rates of first sustained VA within 5 years after disease diagnosis by the 2010 Task Force Criteria between patients with positive and negative PVS. The rates of first episode of rapid VA/(aborted) SCD as well as heart transplant, cardiovascular, and all-cause mortality were also assessed and compared in the 2 groups.

Statistical Analyses

Of important note, a correction of the risk calculator’s baseline survival was issued after its original publication. This article is based on the corrected version.23 Continuous variables were expressed using mean±SD or median [interquartile range], and comparisons were performed using an independent sample Student t test or Mann-Whitney U test, in accordance with their distribution. Categorical variables were reported as counts (percentages) and comparisons run using chi-square or Fisher exact tests, as appropriate. The association between baseline characteristics and PVS inducibility status was tested using univariable logistic regression; those variables that met a significance threshold of 0.10 were included in a multivariable logistic regression model. The association between cycle length of VT induced during PVS and of VA observed during follow-up was tested using linear regression, with strength of association determined using the Pearson correlation coefficient. Rates of VA-free survival were assessed using Kaplan-Meier curves and compared using log-rank testing. The risk of sustained VA at 5 years was predicted for each patient using the ARVC risk calculator (https://www.ARVCrisk.com) and calculated according to Equation 1, where PI is the prognostic index and is calculated according to Equation 2.

| (1) |

| (2) |

Model calibration was assessed visually using a plot of predicted versus observed event rates. All covariates of the ARVC risk calculator had <5% missingness, except for NSVT (6% missingness), 24-hour premature ventricular complex count (11% missingness), and RVEF (12% missingness). Missing quantitative values for RVEF and left ventricular ejection fraction were imputed manually when qualitative assessment was present, in accordance to previously described methods.5 Other missing data used for the ARVC risk calculator were assumed to be missing at random and imputed using multiple imputations with chained equations.24 Complete-case sensitivity analysis was performed to test the effect of this imputation.

To assess the predictive ability of PVS inducibility for VA events, Cox proportional hazards models of VA events were fitted to the result of PVS testing, both as a single coefficient and in conjunction with the ARVC risk calculator PI (incorporated as a fixed offset variable). Model discriminations were assessed using a nonparametric concordance-based C-statistic.25 Both PVS inducibility and the individual coefficients of the ARVC risk calculator fulfilled standard proportional hazards assumption testing criteria. The added value of PVS inducibility to the ARVC risk calculator for predicting VA events was assessed using log-likelihood ratio testing for nested models, with 1 degree of freedom added to the 7 degrees of freedom of the original ARVC risk calculator. Net reclassification improvement for a 5-year risk cutoff of 25% (5% risk/y) was also calculated using standard approximations for time-to-event data.26 Patients were then stratified by ARVC risk calculator predicted risk into “low/intermediate arrhythmic risk” (<5% predicted risk/y; <25% predicted risk during 5 years) and “high arrhythmic risk” (≥5% predicted risk/y; ≥25% predicted risk during 5 years) subcohorts. The sensitivity and specificity of PVS inducibility in the overall cohort, and the positive predictive value and negative predictive value of PVS inducibility in these 2 subgroups, were calculated according to previously published methods for estimating these test metrics in survival data.27 The sensitivity and specificity were then used to determine the effect of the use of PVS in addition to the risk calculator in a given patient using Bayes’ theorem following these sequential equations (Equations 3 through 5):

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

Here, LR is the likelihood ratio and is calculated using Equation 6 for inducible PVS (LR+) and Equation 7 for noninducible PVS (LR–).

| (6) |

| (7) |

All analyses were performed using STATA (v.14.0 STATA Corp, College Station, TX), PyCharm (v 2018.3.6 Community Edition, JetBrains Inc, Boston, MA), and the python Lifelines and statsmodels statistical software package. For all statistical testing, P<0.05 was used as a threshold for significance.

Results

Overall Cohort

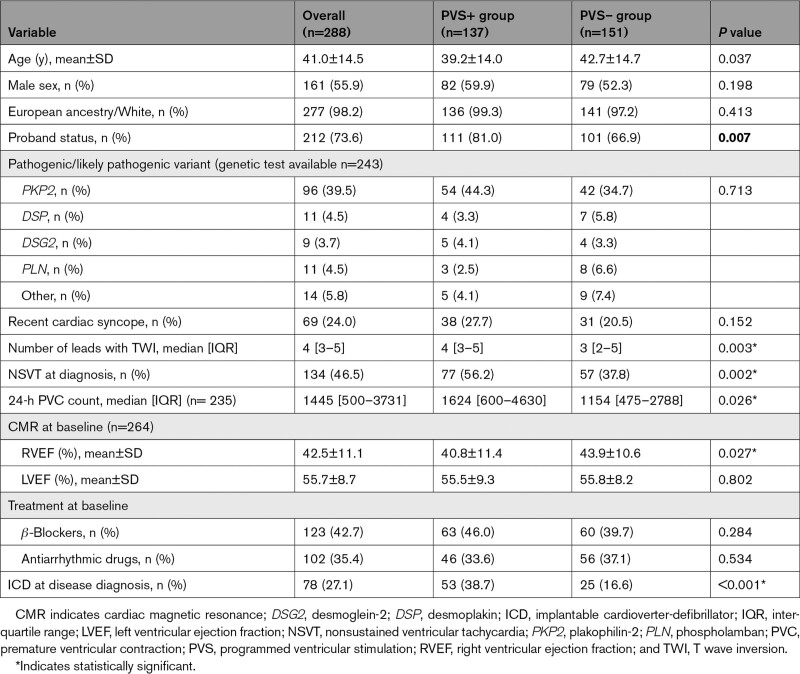

Two hundred eighty-eight definite patients with ARVC who underwent PVS at the time of diagnosis were included in the study. The mean age at diagnosis was 41.0±14.5 years, 55.9% of the patients were male, and 73.6% were probands. Genetic testing was performed in 243 patients (84.4%), 141 (58.0%) of whom harbored ARVC-associated pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants. Variants were most common in plakophilin-2 (PKP2; n=96), followed by desmoplakin (DSP; n=11) and phospholamban (PLN; n=11). Overall characteristics of the study cohort are reported in Table 1. One hundred ninety-nine (69.1%) patients were part of the ARVC risk calculator development cohort,5 and 89 (31%) additional patients were derived from an Italian cohort in which the risk calculator has previously been validated.6 Comparison of the study cohort with the ARVC risk calculator development cohort is reported in Table 2. Patient characteristics per registry have been reported in Section C of the Supplemental Material.

Table 1.

Cohort Characteristics

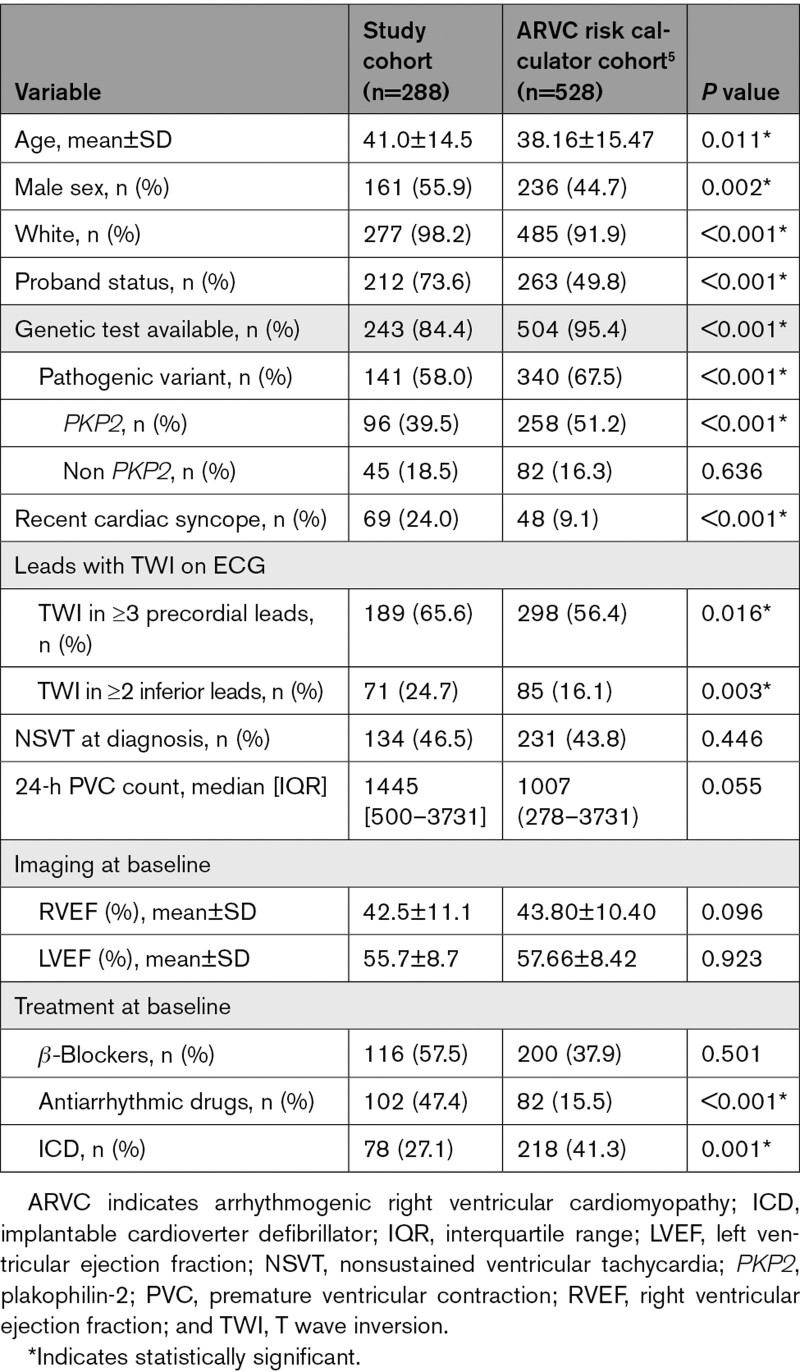

Table 2.

Comparison of the Baseline Characteristics of the Study Cohort and of the Cohort Used for the ARVC Risk Calculator Derivation

Overall, patients who underwent PVS were more likely to be male (55.9% versus 44.7%; P=0.002), more likely to be probands (73.6% versus 49.8%; P<0.001), less likely to be variant carriers (58.0% versus 67.5%; P<0.001), more likely to have had a previous cardiac syncope (24.0% versus 9.1%; P<0.001), had more leads with T wave inversion, and were less likely to have an ICD at baseline (27.1% versus 41.3%; P=0.001). Distribution of the predicted risk of the study population according to the ARVC risk calculator has been reported in Figure S1.

PVS Data

In 215 (88%) patients, a 3 extra stimuli PVS protocol was used, delivered at 2 right ventricle sites (right ventricular apex and outflow tract) in 222 (89%). One hundred thirty-seven (47.6%) patients were inducible with a median of 1.4 [1.2–1.5] sustained VT morphologies induced per patient. The median VT cycle length was 247 [220–280] ms, and the most common morphology was left bundle-branch block (n=158, 72.5%), with a superior axis morphology (33.5%). Table S1 summarizes procedural PVS data.

Inducible patients were younger (39.2±14.0 versus 42.7±14.7 years; P=0.037), were disproportionately probands (81.0% versus 66.9%; P=0.007) and had more leads with T wave inversion on ECG (4 [3–5] versus 2 [2–5]; P=0.003), more NSVT (56.2% versus 37.8%; P=0.002), a higher 24-hour premature ventricular complex burden (1624 [600–4630] versus 1154 [475–2788]; P=0.026), and a lower RVEF (40.8±11.4 versus 43.9±10.6; P=0.027) than patients with no inducible VT. At multivariable analyses, however, the presence of NSVT at diagnosis was the only predictor for PVS inducibility (odds ratio, 2.095 [1.233–3.560]; P=0.006). The complete list of univariable and multivariable predictors of PVS inducibility is reported in Table S2.

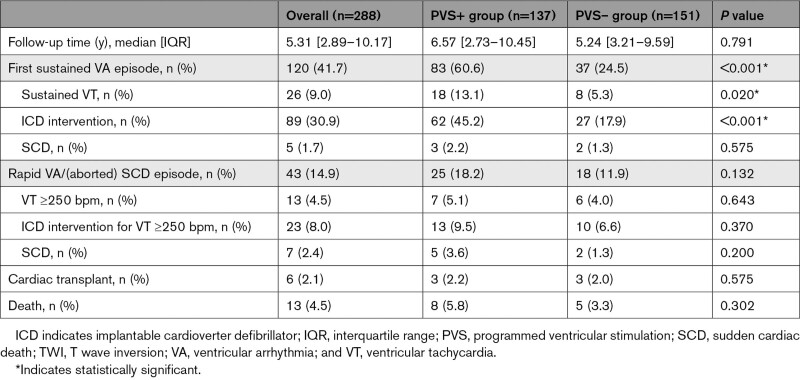

Long-Term Outcomes

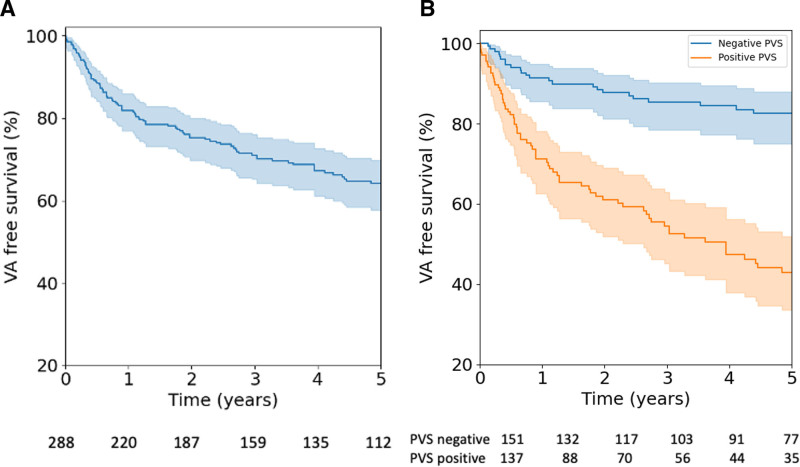

During a median follow-up of 5.31 [2.89–10.17] years, 120 (41.7%) patients experienced a sustained VA event (Table 3). Patients who had a positive PVS were more likely to experience a sustained VA event than those in whom the PVS was negative (83 of 137, 60.6%, versus 37 of 151, 24.5%; P<0.001). A total of 43 rapid VA/(aborted) SCD episodes were observed during follow-up, with no significant differences between those with and without a positive PVS (18.2% versus 11.9%, P=0.132). Overall, 23 episodes (n=19 sustained VT; n=4 fast VT/[aborted] SCD) were experienced by patients without an ICD. At last follow-up, 196 (68.1%) had an ICD in place, 6 (2.1%) had undergone heart transplant, and 13 (4.5%) patients had died. Figure 1A reports the cumulative freedom from first sustained VA in the whole cohort, and Figure 1B reports the cumulative freedom from incident sustained VA stratified by PVS inducibility. Figure S2 represents the timing of ICD implantation. Table S3 reports ICD programming details. Figure S4 reports cycle length concordance between the inducible VT at PVS and the observed clinical VT.

Table 3.

Follow-Up Characteristics of the Study Cohort

Figure 1.

Survival free from sustained VA. Cumulative survival free from sustained VA is presented with 95% CIs (shaded area) in the overall population (A) and according to inducibility of sustained monomorphic VT on PVS (B). PVS indicates programmed ventricular stimulation; and VA, ventricular arrhythmias.

ARVC Risk Calculator and 5-Year Outcomes

During the first 5 years of follow-up, 92 (34.0%) patients had a sustained VA event. Among the variables included in the previously published ARVC risk calculator, younger age (hazard ratio [HR] per year increase, 0.98 [0.97–0.99]; P=0.003), male sex (HR, 1.78 [1.15–2.76]; P=0.009), presence of NSVT (HR, 2.09 [1.30–3.33]; P=0.002), 24-hour premature ventricular complex burden (HR per log increase, 1.148 [1.03–1.29]; P=0.016), and RVEF (HR per percent increase, 0.97 [0.95–0.99]; P=0.001) were significantly associated with the development of sustained VAs in this time period. Figure S3 reports the ARVC risk calculator calibration plot in this cohort, showing a strong correlation between the ARVC risk calculator predicted and observed arrhythmic risk in this cohort (r2 of 0.94).

PVS and Additional Value in Predicting 5-Year Outcomes

Inducibility on PVS predicted sustained VA events during 5 years (HR, 4.21 [2.64–6.71]; P<0.001) on univariable Cox proportional hazards analyses. This predictive ability remained significant (HR, 2.52 [1.58, 4.02]; P<0.001) after adjustment for the ARVC risk calculator predicted risk. The model combining ARVC risk calculator predicted risk and PVS inducibility (C-statistic, 0.75) was superior to univariable Cox proportional hazard models using either PVS inducibility (C-statistic, 0.66) or the ARVC risk calculator (C-statistic, 0.72; log-likelihood ratio, P<0.001). Net reclassification improvement with a 5-year VA risk cutoff of <25% was 7% for the combined model relative to the ARVC risk calculator taken in isolation.

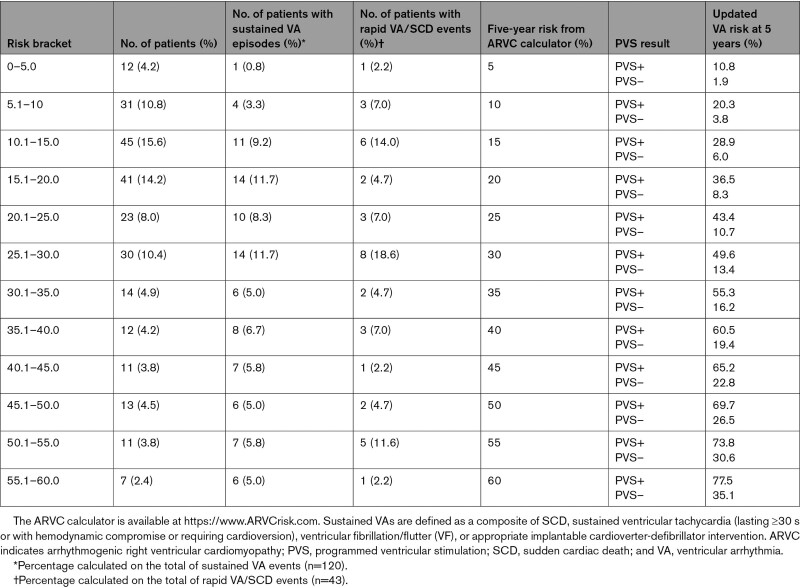

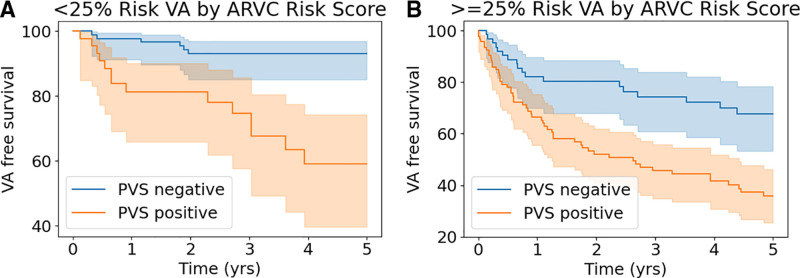

The value of PVS for predicting 5-year sustained VA in the low/intermediate arrhythmic risk group (n=152; n=24 VAs in the 5-year follow-up) versus high arrhythmic risk group (n=136; n=68 VAs in the 5-year follow-up) was as follows: low/intermediate risk group positive predictive value, 38.5% [25.4–51.6] and negative predictive value, 92.6% [87.4–97.5]; high-risk group positive predictive value, 68.4% [58.5–78.3] and negative predictive, value 64.2% [51.2–77.2]. The sensitivity and specificity for PVS in the overall cohort were 75.7% [67.4–84.0] and 67.5% [60.75–74.3], respectively. The corresponding LRs were 2.3 for inducible (LR+) and 0.36 for noninducible PVS (LR–). Table 4 illustrates post-PVS derived VA risk in patients with different pretest predicted 5-year risk according to the ARVC risk calculator. For example, a patient with a 5-year ARVC risk prediction of 25% will have a 5-year posttest VA risk of 12.3% if noninducible during PVS, and of 44.4% if inducible. The updated online calculator integrating the use of PVS is available at arvcrisk.com. Figure 2A and 2B shows the cumulative survival free from sustained VA for inducible and noninducible patients in the low/intermediate arrhythmic and high arrhythmic risk groups. A complete-case sensitivity analysis yielded similar results (Supplemental Material Section B).

Table 4.

Examples of Updated VA Risk According to PVS Results (Inducible or Noninducible) in Patients With Different A Priori 5-Year Risks From the ARVC Calculator

Figure 2.

Survival free from ventricular arrhythmia (VA) stratified by risk group. Cumulative survival free from sustained VA with 95% CIs (shaded area) according to inducibility of sustained monomorphic VT on PVS in patients with a 5-year predicted ARVC risk <25% (low/intermediate arrhythmic risk group; A) and ≥25% (high risk group; B) according to the online risk calculator (https://www.ARVCrisk.com). ARVC indicates arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy; PVS, programmed ventricular stimulation; and VA, ventricular arrhythmias.

Discussion

The main findings of this study can be summarized as follows: first, nearly half (47.6%) of this cohort of 288 patients referred for PVS had inducible sustained VA. Second, we found that inducibility at PVS could predict the occurrence of sustained VA during the 5 years follow-up. Last, we showed that adding the inducibility on PVS to the current ARVC risk calculator significantly improved the model discrimination. It is important that, PVS was shown to have a high negative predictive value (92.6%) for incident sustained VA at 5 years in patients with an ARVC risk calculator predicted 5-year risk <25%, and PVS results can be used together with the risk calculator to refine predictions in individual patients.

Risk Stratification in Patients With ARVC

Once a diagnosis of ARVC is established, the next step in the clinical management is to assess the patient’s risk of experiencing a sustained VA and to determine if an ICD is warranted.3 In the past 3 decades, multiple studies have aimed to identify the predictors of sustained VA in ARVC. A recent meta-analysis by Bosman et al28 summarized those predictors and paved the way to the development of a novel risk stratification tool,5 which integrates multiple noninvasive parameters.

This published ARVC risk calculator (https://www.ARVCrisk.com) aims to predict the 5-year risk of the first sustained VA event in patients with definite ARVC. Multiple independent cohorts have reported good reliability of this risk calculator in different settings6,7,9,10 and also confirmed its superiority to currently available risk stratification algorithms.6,7 By including only patients referred for a PVS, this study cohort not surprisingly had a higher ARVC risk calculator–predicted risk than the previous cohorts, in which the ARVC risk calculator was developed and validated. Nonetheless, the ARVC risk calculator showed good performance (calibration slope=0.92 and C-statistic, 0.72) in predicting the 5-year outcomes in this subpopulation as well.

PVS in ARVC Arrhythmic Risk Stratification

The utility of sustained VT inducibility on PVS as a predictor of VA in ARVC has drawn significant attention in previous literature. Although some investigators have reported its clinical utility in predicting long-term arrhythmic outcomes,6,14,15,18 other studies found a positive predictive value as low as 35% for PVS in this patient population.20 Because of its invasive nature, precluding its use in all patients, PVS was not included in the original ARVC risk calculator. The possibility that integrating the results of PVS with the ARVC risk calculator might further improve risk estimates was postulated soon after its publication.13

The primary purpose of this study was to better define the contemporary role of PVS in risk stratification of patients with ARVC who do not present with a sustained VA. This study is unique not only because of its large size (with an international cohort of 288 primary prevention ARVC patients, it is, to our knowledge, the largest report of PVS in ARVC to date), but also because we examined the incremental predictive value of PVS on the recently published ARVC risk calculator. A strong correlation between sustained VT inducibility and arrhythmic outcomes was clearly observed during a median follow-up of >5 years. Patients in whom sustained arrhythmias were induced during PVS had a 4-fold risk of sustained VA events during follow-up. Furthermore, we showed that PVS results provide additional value when integrated with the existing ARVC risk calculator. A model that combined both PVS and the ARVC risk calculator–predicted risk was superior at predicting 5-year arrhythmic outcomes than either of these 2 predictors alone.

Clinical Implications

An important clinical question that may arise is the role of PVS in guiding primary prevention ICD placement in patients with ARVC. The results of this study suggest that PVS may be of value in the risk stratification process of patients who have a low/intermediate predicted risk (<25% at 5 years) on the basis of the ARVC risk calculator (Table 4). In patients with VA predicted risks at the extremes (either very high or very low per the calculator), an invasive PVS procedure would likely be of limited use. Conversely, this additional stratification tool can be of greatest use in the clinical decision-making process in patients with an intermediate predicted risk. In this study, a negative PVS had a high negative predictive value (92.6%) in patients at low/intermediate predicted risk (<25% at 5 years) per the risk calculator. This makes a robust argument in favor of the use of a negative PVS to support a clinical decision not to implant an ICD in patients in whom the risk score suggests a low or an intermediate predicted risk. In addition, PVS results can be directly integrated into the ARVC risk calculator in an adjusted approach to refine risk prediction in individual patients using Bayes’ theorem. This personalized approach can help in selecting patients who are most likely to benefit from this invasive procedure to facilitate the therapeutic decision about ICD use.

Limitations

All centers involved are tertiary, high-volume referral centers, and some degree of selection bias in patient enrollment cannot be ruled out. Furthermore, patients were selected for this study on the basis of their referral for PVS, which relied on clinical decision-making of individual cardiologists. Consequently, patients at very low predicted risk, patients at less advanced disease stages, and family members are underrepresented in this cohort referred for an invasive risk stratification method. The generalizability of our findings to these other types of patients with ARVC is unclear. As with any clinical predictive model, validation in an external cohort will be important for the clinical implementation of this additive method to the ARVC risk calculator. In addition, the predicted outcome of any sustained VA, which included sustained VA and ICD-treated arrhythmia, cannot be considered a strict surrogate of SCD. Specifically for rapid VA/(aborted) SCD, rates were numerically larger for patients with PVS+ than for patients with PVS–, but the difference did not reach statistical significance, expressing limited power or a lack of predictive ability. Adequately powered studies aimed at addressing this specific outcome would be of great use in the future. However, because of the appropriate use of ICDs and more timely diagnosis, SCD has fortunately become a rare event in patients with ARVC. The primary aim of most studies has therefore shifted away from overall/cardiovascular mortality and SCD toward the overall burden of sustained VA events, for which a clear difference between patients with positive and negative PVS is observed.

Conclusion

In this multicenter cohort of primary prevention patients with ARVC referred for PVS, sustained VT inducibility on PVS significantly improved the prediction of arrhythmic outcomes 5 years after diagnosis beyond the ARVC risk calculator. A 2-step approach integrating PVS into the risk calculator’s prediction can further refine risk estimates, improving the decision-making process about ICD implantation in selected patients with ARVC.

Article Information

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patients with ARVC and families who have made this work possible. The authors also thank Jeroen van der Heijden, MD, PhD; Peter Loh, MD, PhD; Mimount Bourfiss, MD; Rob W. Roudijk, MD; and Machteld J. Boonstra, MSc. J.P.v.T and A.A.M.W. are Member of the European Reference Network for rare, low prevalence and complex diseases of the heart: ERN GUARD-Heart (ERN GUARDHEART; http://guardheart.ern-net.eu).

Sources of Funding

The Johns Hopkins Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Dysplasia/Cardiomyopathy (ARVD/C) Program is supported by the Leonie-Wild Foundation, the Leyla Erkan Family Fund for ARVD Research, the Hugh Calkins, Marvin H. Weiner, and Jacqueline J. Bernstein Cardiac Arrhythmia Center, the Dr. Francis P. Chiramonte Private Foundation, the Dr. Satish, Rupal, and Robin Shah ARVD Fund at Johns Hopkins, the Bogle Foundation, the Healing Hearts Foundation, the Campanella Family, the Patrick J. Harrison Family, the Peter French Memorial Foundation, the Wilmerding Endowments, Fondation Leducq, and UL1TR001079 (National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences). This work was performed during Dr Gasperetti’s tenure as the Wilton W. Webster Fellowship in Clinical Cardiac Catheter Ablation Fellow of the Heart Rhythm Society; Dr Cadrin-Tourigny’s work is supported by the Philippa and Marvin Carsley cardiology research chair and the Montreal Heart Institute Foundation. The Zurich ARVC Program is supported by the Georg und Bertha Schwyzer-Winiker Foundation, Baugarten Foundation, Leonie-Wild Foundation, Swiss Heart Foundation grants FF17019 and FF21073‚ and Swiss National Science Foundation grant 160327. Dr Platonov’s work in the Nordic ARVC Registry is supported by the Swedish Heart Lung Foundation (grant 20200674), and support from the Swedish state under the Avtal om läkarutbildning och forsknin (ALF)-agreement. The Dutch ARVC registry (Drs van Tintelen, and Wilde, and te Riele) is funded by the Netherlands Cardiovascular Research Initiative, with support of the Dutch Heart Foundation (grant CVON2015-12/2018-30 eDETECT/PREDICT2).

Disclosures

Dr Tondo serves as member of the Advisory Board of Medtronic and Boston Scientific. He receives lecture and proctoring fees from Medtronic, Abbott, and Boston Scientific. Dr Saguner received educational grants through his institution from Abbott, Bayer Healthcare, Biosense Webster, Biotronik, Boston Scientific, BMS/Pfizer, and Medtronic; and speaker/advisory board/consulting fees from StrideBio Inc‚ Bayer Healthcare, Daiichi-Sankyo, Medtronic, Novartis, and Pfizer. C. Tichnell is a consultant for StrideBio Inc. Dr James is a consultant for Pfizer, Tenaya Inc, and StrideBio Inc. Dr Caulkins is a consultant for Medtronic, Biosense Webster, Pfizer, StrideBio Inc, and Abbott. He receives research support from Boston Scientific. C. Tichnell and Dr James receive salary support from this grant from Boston Scientific. Dr Cadrin-Tourigny is a consultant for Tenaya Inc. The other authors report no conflicts.

Supplemental Material

Tables S1–S3

Figures S1–S4

Section B—Complete Case Analysis

Section C—Patients' Characteristics by Registry

Supplementary Material

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- ARVC

- arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy

- HR

- hazard ratio

- ICD

- implantable cardioverter defibrillator

- LR

- likelihood ratio

- NSVT

- nonsustained ventricular tachycardia

- PVS

- programmed ventricular stimulation

- SCD

- sudden cardiac death

- VA

- ventricular arrhythmia

- VT

- ventricular tachycardia

Circulation is available at www.ahajournals.org/journal/circ

A.M. Saguner and J. Cadrin-Tourigny contributed equally.

Supplemental Material is available at https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/suppl/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.122.060866.

For Sources of Funding and Disclosures, see page 1442.

Contributor Information

Alessio Gasperetti, Email: agasper3@jhmi.edu.

Richard T. Carrick, Email: rcarric5@jh.edu.

Sarah Costa, Email: sarah.costa1193@gmail.com.

Paolo Compagnucci, Email: paolocompagnucci1@gmail.com.

Laurens P. Bosman, Email: L.P.Bosman-3@umcutrecht.nl.

Monica Chivulescu, Email: monica.chivulescu@yahoo.com.

Crystal Tichnell, Email: ctichnell@jhmi.edu.

Brittney Murray, Email: bdye1@jhmi.edu.

Harikrishna Tandri, Email: htandri1@jhmi.edu.

Rafik Tadros, Email: rafik.tadros@umontreal.ca.

Lena Rivard, Email: lena.rivard@gmail.com.

Maarten P. van den Berg, Email: m.p.van.den.berg@umcg.nl.

Katja Zeppenfeld, Email: K.Zeppenfeld@lumc.nl.

Arthur A.M. Wilde, Email: a.a.wilde@amc.uva.nl.

Giulio Pompilio, Email: giuliopompilio1@yahoo.com.

Corrado Carbucicchio, Email: corrado.carbucicchio@ccfm.it.

Antonio Dello Russo, Email: adellorusso3@yahoo.com.

Michela Casella, Email: michela.casella@gmail.com.

Anneli Svensson, Email: Anneli.Svensson@regionostergotland.se.

Corinna B. Brunckhorst, Email: corinna.brunckhorst@usz.ch.

J. Peter van Tintelen, Email: j.p.vantintelen-3@umcutrecht.nl.

Pyotr G. Platonov, Email: pyotr.platonov@med.lu.se.

Kristina H. Haugaa, Email: kristina.haugaa@medisin.uio.no.

Firat Duru, Email: firat.duru@usz.ch.

Anneline S.J.M. te Riele, Email: ariele3@umcutrecht.nl.

Paul Khairy, Email: paul.khairy@umontreal.ca.

Claudio Tondo, Email: claudio.tondo@cardiologicomonzino.it.

Hugh Calkins, Email: hcalkins@jhmi.edu.

Cynthia A. James, Email: cjames7@jhmi.edu.

Ardan M. Saguner, Email: ardansaguner@yahoo.de.

References

- 1.Corrado D, Link MS, Calkins H. Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:61–72. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1509267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Towbin JA, McKenna WJ, Abrams DJ, Ackerman MJ, Calkins H, Darrieux FCC, Daubert JP, de Chillou C, DePasquale EC, Desai MY, et al. 2019 HRS expert consensus statement on evaluation, risk stratification, and management of arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy: executive summary. Heart Rhythm. 2019;16:e373–e407. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2019.09.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Corrado D, Wichter T, Link MS, Hauer R, Marchlinski F, Anastasakis A, Bauce B, Basso C, Brunckhorst C, Tsatsopoulou A, et al. Treatment of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy/dysplasia: an international task force consensus statement. Eur Heart J. 2015;36:3227–3237. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Calkins H, Corrado D, Marcus F. Risk stratification in arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2017;136:2068–2082. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.030792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cadrin-Tourigny J, Bosman LP, Nozza A, Wang W, Tadros R, Bhonsale A, Bourfiss M, Fortier A, Lie ØH, Saguner AM, et al. A new prediction model for ventricular arrhythmias in arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Eur Heart J. 2019;40:1850–1858. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Casella M, Gasperetti A, Gaetano F, Busana M, Sommariva E, Catto V, Sicuso R, Rizzo S, Conte E, Mushtaq S, et al. Long-term follow-up analysis of a highly characterized arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy cohort with classical and non-classical phenotypes–a real-world assessment of a novel prediction model: does the subtype really matter. EP Europace. 2020;22:797–805. doi: 10.1093/europace/euz352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aquaro GD, De Luca A, Cappelletto C, Raimondi F, Bianco F, Botto N, Barison A, Romani S, Lesizza P, Fabris E, et al. Comparison of different prediction models for the indication of implanted cardioverter defibrillator in patients with arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. ESC Heart Failure. 2020;7:4080–4088. doi: 10.1002/ehf2.13019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gasperetti A, Rossi VA, Chiodini A, Casella M, Costa S, Akdis D, Büchel R, Deliniere A, Pruvot E, Gruner C, et al. Differentiating hereditary arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy from cardiac sarcoidosis fulfilling 2010 ARVC Task Force Criteria. Heart Rhythm. 2021;18:231–238. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2020.09.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aquaro GD, De Luca A, Cappelletto C, Raimondi F, Bianco F, Botto N, Lesizza P, Grigoratos C, Minati M, Dell’Omodarme M, et al. Prognostic value of magnetic resonance phenotype in patients with arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:2753–2765. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baudinaud P, Laredo M, Badenco N, Rouanet S, Waintraub X, Duthoit G, Hidden-Lucet F, Redheuil A, Maupain C, Gandjbakhch E. External validation of a risk prediction model for ventricular arrhythmias in arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Can J Cardiol. 2021;37:1263–1266. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2021.02.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jordà P, Bosman LP, Gasperetti A, Mazzanti A, Gourraud JB, Davies B, Frederiksen TC, Weidmann ZM, Di Marco A, Roberts JD, et al. Arrhythmic risk prediction in arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy: external validation of the arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy risk calculator. Eur Heart J. 2022;43:3041–3052. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehac289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Protonotarios A, Bariani R, Cappelletto C, Pavlou M, García-García A, Cipriani A, Protonotarios I, Rivas A, Wittenberg R, Graziosi M, et al. Importance of genotype for risk stratification in arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy using the 2019 ARVC risk calculator. Eur Heart J. 2022;43:3053–3067. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehac235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McKenna WJ, Asaad NA, Jacoby DL. Prediction of ventricular arrhythmia and sudden death in arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Eur Heart J. 2019;40:1859–1861. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bhonsale A, James CA, Tichnell C, Murray B, Gagarin D, Philips B, Dalal D, Tedford R, Russell SD, Abraham T, et al. Incidence and predictors of implantable cardioverter-defibrillator therapy in patients with arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy undergoing implantable cardioverter-defibrillator implantation for primary prevention. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:1485–1496. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.06.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Orgeron GM, James CA, Te Riele A, Tichnell C, Murray B, Bhonsale A, Kamel IR, Zimmerman SL, Judge DP, Crosson J, et al. Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator therapy in arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy: predictors of appropriate therapy, outcomes, and complications. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6:e006242. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.117.006242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Piccini JP, Dalal D, Roguin A, Bomma C, Cheng A, Prakasa K, Dong J, Tichnell C, James C, Russell S, et al. Predictors of appropriate implantable defibrillator therapies in patients with arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia. Heart Rhythm. 2005;2:1188–1194. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2005.08.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roguin A, Bomma CS, Nasir K, Tandri H, Tichnell C, James C, Rutberg J, Crosson J, Spevak PJ, Berger RD, et al. Implantable cardioverter-defibrillators in patients with arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:1843–1852. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.01.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saguner AM, Medeiros-Domingo A, Schwyzer MA, On CJ, Haegeli LM, Wolber T, Hürlimann D, Steffel J, Krasniqi N, Rüeger S, et al. Usefulness of inducible ventricular tachycardia to predict long-term adverse outcomes in arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 2013;111:250–257. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2012.09.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maupain C, Badenco N, Pousset F, Waintraub X, Duthoit G, Chastre T, Himbert C, Hébert JL, Frank R, Hidden-Lucet F, et al. Risk stratification in arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy/dysplasia without an implantable cardioverter defibrillator. JACC Clin Electrophysiol. 2018;4:757–768. doi: 10.1016/j.jacep.2018.04.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Corrado D, Calkins H, Link MS, Leoni L, Favale S, Bevilacqua M, Basso C, Ward D, Boriani G, Ricci R, et al. Prophylactic implantable defibrillator in patients with arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy/dysplasia and no prior ventricular fibrillation or sustained ventricular tachycardia. Circulation. 2010;122:1144–1152. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.913871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marcus FI, McKenna WJ, Sherrill D, Basso C, Bauce B, Bluemke DA, Calkins H, Corrado D, Cox MG, Daubert JP, et al. Diagnosis of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy/dysplasia: proposed modification of the Task Force Criteria. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:806–814. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, Bick D, Das S, Gastier-Foster J, Grody WW, Hegde M, Lyon E, Spector E, et al. ; ACMG Laboratory Quality Assurance Committee. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015;17:405–424. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cadrin-Tourigny J, Bosman LP, Nozza A, Wang W, Tadros R, Bhonsale A, Bourfiss M, Fortier A, Lie ØH, Saguner AM, et al. A new prediction model for ventricular arrhythmias in arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Eur Heart J. 2022;43:e1–e9. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehac180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.White IR, Royston P. Imputing missing covariate values for the Cox model. Stat Med. 2009;28:1982–1998. doi: 10.1002/sim.3618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gönen M, Heller G. Concordance probability and discriminatory power in proportional hazards regression. Biometrika. 2005;92:965–970. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pencina MJ, D’Agostino RB, Sr, Steyerberg EW. Extensions of net reclassification improvement calculations to measure usefulness of new biomarkers. Stat Med. 2011;30:11–21. doi: 10.1002/sim.4085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heagerty PJ, Lumley T, Pepe MS. Time-dependent ROC curves for censored survival data and a diagnostic marker. Biometrics. 2000;56:337–344. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2000.00337.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bosman LP, Sammani A, James CA, Cadrin-Tourigny J, Calkins H, van Tintelen JP, Hauer RNW, Asselbergs FW, Te Riele ASJM. Predicting arrhythmic risk in arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart Rhythm. 2018;15:1097–1107. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2018.01.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.