Abstract

PAX5, a master regulator of B cell development and maintenance, is one of the most common targets of genetic alterations in B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL). PAX5 alterations consist of copy number variations (whole gene, partial, or intragenic), translocations, and point mutations, with distinct distribution across B-ALL subtypes. The multifaceted functional impacts such as haploinsufficiency and gain-of-function of PAX5 depending on specific variants have been described, thereby the connection between the blockage of B cell development and the malignant transformation of normal B cells has been established. In this review, we provide the recent advances in understanding the function of PAX5 in orchestrating the development of both normal and malignant B cells over the past decade, with a focus on the PAX5 alterations shown as the initiating or driver events in B-ALL. Recent large-scale genomic analyses of B-ALL have identified multiple novel subtypes driven by PAX5 genetic lesions, such as the one defined by a distinct gene expression profile and PAX5 P80R mutation, which is an exemplar leukemia entity driven by a missense mutation. Although altered PAX5 is shared as a driver in B-ALL, disparate disease phenotypes and clinical outcomes among the patients indicate further heterogeneity of the underlying mechanisms and disturbed gene regulation networks along the disease development. In-depth mechanistic studies in human B-ALL and animal models have demonstrated high penetrance of PAX5 variants alone or concomitant with other genetic lesions in driving B-cell malignancy, indicating the altered PAX5 and deregulated genes may serve as potential therapeutic targets in certain B-ALL cases.

Keywords: PAX5, PAX5 alterations, B cell development, B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia, driver genetic lesions, B-ALL subtype, PAX5alt, PAX5 P80R

Background

B lymphocytes are known for generating countless high-affinity antibodies against foreign pathogens. The development of B cells starts in the bone marrow, where the hematopoietic stem cells hierarchically differentiate into fate-restricted progenitors, eventually giving rise to immature B cells heading to the spleen, where B cells further differentiate into mature B cells. This process is highly elaborate and orchestrated by a combination of intracellular mechanisms and external stimuli. Among them, PAX5 (paired box 5), or BSAP (B-cell-specific activator protein), is the pivotal transcription factor commanding the B cell development. It has been well-established that PAX5 is not only required to initiate B-lineage commitment but also essential for the maintenance of B cell identity by repressing signature genes of other lineages during the whole differentiation process.

Accompanied by the gradually uncovered mechanisms of PAX5 in normal B lymphopoiesis, extensive studies have revealed that deregulated PAX5 activities by somatic or germline alterations may lead to B-cell malignancies. Recent advances in genome-wide assays have greatly accelerated the discovery of genomic variants in B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL). SNP microarray and DNA sequencing of large cohorts of pediatric and adult B-ALL samples revealed diverse genetic lesions, of which PAX5 was ranked the most frequently altered gene being detected in around one-third of B-ALL cases ( Table 1 ) (1, 2, 6). The prevalence of PAX5 alterations has been continually emphasized in different cohorts of B-ALL (3, 5, 7, 9, 10, 12, 15), with two B-ALL subtypes even defined by PAX5 genetic lesions and distinct gene expression profiles (GEPs) (16). PAX5 genetic lesions are heterogeneous, including deletions, rearrangements, sequence mutations, and focal intragenic amplifications (iAmp), which lead to the haploinsufficiency or gain-of-function of PAX5 depending on specific variants (1, 2, 8, 16). Rather than secondary events, increasing evidence from recent multi-omics and mechanistic studies has demonstrated that PAX5 alterations can function as the initiating genetic lesions for B-ALL. In this review, we summarize recent advances in understanding the function of PAX5 in both normal and malignant B cells, with a focus on the PAX5 alterations as founder events in B-ALL.

Table 1.

PAX5 alterations in B-ALL.

| Cohort | Platform | Comments on PAX5 alteration | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| 242 pediatric ALL | SNP array | PAX5 gene is the most frequent target of somatic mutation, being altered in 31.7% of cases. | (1) |

| 40 pediatric ALL | SNP array | Cell cycle and B cell related genes, including PAX5, are the most frequent mutated genes. | (2) |

| 304 ALL samples | SNP array | Deletion of PAX5 in 51% BCR::ABL1 cases, of which 95% have a deletion of IKZF1. | (3) |

| 61 pediatric B-ALL (diagnosis & relapse) |

SNP array | Around 50% of B-ALL have CNAs in genes known to regulate B-lymphoid development, especially in PAX5 and IKZF1 genes. | (4) |

| 399 pediatric ALL | SNP array | 7 cases harbor PAX5 fusions. | (5) |

| 221 pediatric B-ALL (high-risk) |

SNP array, GEP array, target sequencing | PAX5 CNA is involved in 31.7% of patients; P80R is the most frequent mutation. | (6) |

| 466 pediatric ALL | FISH | PAX5 rearrangements occur in 2.5% of B-ALL. | (7) |

| 117 adult B-ALL | FISH, qPCR, target sequencing | PAX5 is mutated in 34% of adult B-ALL. P80R is the most frequent point mutation. PAX5 deletion is a secondary event. | (8) |

| 153 adult and pediatric B-ALL with 9p abnormalities | SNP array, FISH | PAX5 has internal rearrangements in 21% of the cases. Malignant cells carrying PAX5 fusion genes displayed a simple karyotype. | (9) |

| 89 Ph+ B-ALL | SNP array | PAX5 genomic deletions were identified in 29 patients (33%). In all cases, the deletion was heterozygous. | (10) |

| Two B-ALL families | WES, SNP array | Germline PAX5 G183S confers susceptibility to B-ALL. | (11) |

| 116 B-ALL | MLPA | 5 cases with PAX5 intragenic amplifications were identified. | (12) |

| One B-ALL family | SNP array | A third B-ALL family carrying germline G183S mutation. | (13) |

| 798 adult B-ALL | GEP array, SNP array, RNA-seq | 38% of Ph-like B-ALL have PAX5 alterations. Enrichment of CNA of IKZF1, PAX5, EBF1, and CDKN2A/B observed in the Ph-like subtype. | (14) |

| 79 B-ALL with PAX5 iAmp | MLPA, FISH, SNP array | PAX5 iAmp defines a novel, relapse-prone subtype of B-ALL with a poor outcome. | (15) |

| 1,988 B-ALL | RNA-seq, WGS, WES, SNP array | Detailed description of PAX5 alterations in B-ALL. Defined the PAX5alt and PAX5 P80R subtypes. | (16) |

| 110 pediatric B-others | RNA-seq, WES, SNP array | PAX5 fusions, iAmp and P80R mutations are mutually exclusive, altogether accounting for 20% of the B-other group. PAX5 P80R is associated with a specific gene expression signature. | (17) |

| 250 B-ALL | DNA methylation array, WES, RNA-seq | 16 patients with P80R grouped into an individual subgroup with biallelic PAX5 alterations. | (18) |

| 1,028 pediatric B-ALL | SNP array | 20 cases of PAX5 P80R with intermediate or poor outcome compared to the rest of this cohort. | (19) |

| One B-ALL family | WES, RNA-seq | PAX5 R38H germline mutation was identified in a family with B-ALL. | (20) |

CNA, copy number alterations; GEP, gene expression profile; WGS, whole genome sequencing; WES, whole exome sequencing; FISH, fluorescence in situ hybridization; MLPA, multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification; RNA-seq, whole transcriptome sequencing.

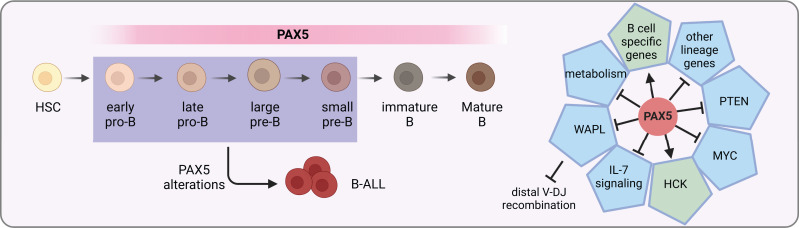

The function of PAX5 in B cell development

The multifaceted roles of PAX5 in B cell development and differentiation have been gradually unveiled. In blood cells, PAX5 expression is exclusively restricted to the B lineage, beginning from the early pre-pro B cells and maintained through the whole process of B cell development ( Figure 1 ) (27). Expression levels of PAX5 are correlated with B cell developmental stages (28). During terminal differentiation from mature B cells to plasma cells, physiological down-regulation of PAX5 is observed (29). This repression is not necessary for plasma cell development but essential for optimal IgG production (30). Constitutive deletion of Pax5 in mice failed to produce mature B cells owing to a complete arrest of B lymphopoiesis at an early pro-B stage in the bone marrow (31). In contrast, B cell development is blocked at an earlier stage even before the appearance of B220+ progenitors in the fetal liver, suggesting different roles of PAX5 in fetal and postnatal B lymphopoiesis (31, 32). Without Pax5, pro-B cells retain lineage-promiscuous capacity that can differentiate into other lineages upon stimulation with proper cytokines (32–34). Therefore, PAX5 is not only required for B lymphopoiesis initiation but also continuously required for its maintenance (34). Conditional inactivated Pax5 expression from pro-B to mature B cell stages leads to down-regulation of B-cell-specific genes and preferential loss of mature B cells, indicating that PAX5 is essential for maintaining the identity of B cells during late B lymphopoiesis (35). Further investigation of deleting Pax5 in immature B cells in the spleen results in the loss of B-1a, marginal zone, and germinal center B cells as well as plasma cells (22). Finally, Pax5-deficient follicular B cells fail to proliferate due to the inhibition of PI3K signaling via PTEN up-regulation (22).

Figure 1.

PAX5 functions in B cell development. PAX5 is expressed during the whole B cell developmental stages. It activates the expression of B cell specific genes, while at the same time represses the expression of other lineage genes to initiate and maintain the B cell identity. In MYD88-driven B-cell lymphomas, it activates the pro-survival kinase HCK (21). In addition, it activates PI3K signaling via PTEN inhibition to stimulate follicular B cell proliferation (22). Furthermore, PAX5 safeguards leukemic transformation by limiting glucose and energy supply, inhibiting IL-7 signaling as well as MYC expression (23–25). Finally, PAX5 also has an essential role in the V(D)J recombination of the IgH locus by repressing WAPL expression (26). PAX5 alterations with compromised activity can lead to developmental arrest of B cells, which are commonly seen in B-ALL.

PAX5 safeguards the development of B cells by tailoring the gene expression profile towards the B-lineage program. On one hand, it up-regulates the expression of B-cell-specific genes such as CD19 and BLNK (36). On the other hand, it down-regulates lineage-inappropriate genes such as FLT3 and CCL3 to suppress alternative lineage choices ( Figure 1 ) (33, 37). Both activation and repression require its continuous expression (37). ChIP analysis revealed that through binding to promoters and enhancers, PAX5 directly regulates 44% of previous identified PAX5-activated genes and 24% of repressed genes (38). For PAX5 activated genes, it can induce active chromatin marks at their regulatory elements (36, 38). For example, PAX5 activates HCK transcription by inducing active chromatin in the HCK promoter in MYD88-mutated lymphoma cells (21). Conversely, it can also modify the chromatin state of its repressed genes by eliminating active histone marks (38).

PAX5 is part of a complex network of transcription factors orchestrating B cell development, including IKZF1, E2A, EBF1, and RUNX1 (23, 39, 40). Together with IKZF1, PAX5 functions as a metabolic gatekeeper to restrict glucose and energy supply. Heterozygous deletion of Pax5 releases this restriction and increases glucose uptake and ATP levels (23). Furthermore, PAX5 is found in a physiological complex together with IKZF1 and RUNX1. Specifically, over 65% of PAX5 binding sites identified in mouse pre-B cells are overlapped with regions bound by either IKZF1, RUNX1, or both, suggesting that they are part of a regulatory network sharing a multitude of target genes (40). In addition, PAX5 and EBF1 are actively involved in a reciprocal positive regulatory loop (41, 42), yet with opposing roles in Myc regulation through binding to the Myc promoter (24). They also cooperatively regulate IL-7 signaling and folate metabolism (25).

A signature feature of B cells is the recombination of VHDJH segments to generate a functional immunoglobulin heavy chain (IgH) gene for B cell receptor and antibody coding. PAX5 contributes to the diversity of the antibody repertoire by balancing distal-proximal VH gene choices. The first insight into the VHDJH recombination role of PAX5 was provided by the observation that, in Pax5-deleted mouse pro-B and pre-B-I (large pre-B) cells, recombination of distal but not proximal VH genes was dramatically compromised (43, 44). Further experiments uncovered that PAX5 can mediate spatial organization of the Igh locus to balance the accessibility of distal and proximal VH genes (45). The mystery of this spatial regulation remained unsolved for more than a decade. Recently, it was found that PAX5 specifically inhibits the expression of WAPL, which encodes an architectural protein that releases the cohesin complex from chromatin ( Figure 1 ) (26). With decreased levels of WAPL protein, chromatin loops are able to extrude for a longer distance to spatially connect the distal VH genes with the recombination center during the loop extrusion process (26). Thus, PAX5 fulfills a master regulator role for B lymphopoiesis by, but not limited to, inducing B-lineage commitment, maintaining B cell identity, and regulating VHDJH recombination.

Copy-number alterations of PAX5 in B-ALL

Deletion is the most frequent form of copy number alteration of PAX5 in B-ALL (1, 6, 8, 16). PAX5 deletions usually affect only one allele, with either no expression or expression of truncated proteins lacking functional domains, resulting in loss of function of this allele (1). These monoallelic PAX5 deletions in B-ALL are observed on different scales, from as focal as deletion of exons within PAX5 gene body, to as large as loss of 9p arm or whole chromosome 9 where PAX5 gene is located (1). In B-ALL, PAX5 deletions are commonly concurrent with complete loss of CDKN2A/B genes, which encode key cell cycle regulators also situated in chromosome 9p (8, 46). Notably, PAX5 deletions are associated with complex karyotype which is thought to be a secondary or late event, indicating the requirement of other oncogenic lesions to cause overt malignant transformation (1, 8). In support of this notion, PAX5 deletions were found in over 50% of BCR::ABL1 and 18% of TCF3::PBX1 B-ALL cases (3, 8, 10), and were enriched in Ph-like B-ALL patients as well (14).

Studies using mouse models showed that haploinsufficiency of Pax5 caused by monoallelic deletion exerted susceptibility of B cell transformation. Mice with heterozygous loss of Pax5 show normal B cell development and never develop leukemia (47). But with the acquisition of other oncogenic events, they can spontaneously develop B-lineage leukemia. For example, Pax5+/- cooperated with STAT5 activation can initiate B-ALL with full penetrance in mice (47). Furthermore, compound heterozygous mutations in Pax5 and Ebf1 dramatically increase ALL frequency in mice (48), which is associated with the hyperactivation of the IL-7 signaling pathway (25). When synergized with BCR::ABL1 in hematopoietic stem cells, Pax5+/- gives rise to B-ALL with shorter latencies and high incidence compared to BCR::ABL1 alone (49). This synergistic effect may explain the frequent PAX5 deletions in BCR::ABL1 B-ALL cases (3, 10). Finally, in Pax5+/- mice, Jak3 mutations following postnatal infections can also act as a secondary hit for leukemic transformation (50).

The indispensable role of PAX5 in B-lineage maintenance also explains the monoallelic but not biallelic deletions of PAX5 observed in B-ALL cases. Complete loss of Pax5 in mice resulted in the lack of B cells, growth retardation, and premature death (31). When Pax5 deficiency is restricted to mature B cells to circumvent premature death, these cells dedifferentiate back into uncommitted progenitors and develop aggressive progenitor cell tumors instead of B-ALL (51). Therefore, PAX5 deletions often disrupt only one allele and act as cooperating events in B-ALL.

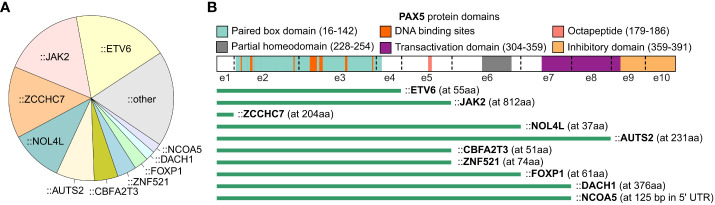

Translocations

Translocations resulting in PAX5 rearrangements occur in around 2.5% of pediatric and 1% of adult B-ALL patients (8). The majority of the rearrangements produce chimeric genes encoding proteins that retain the DNA-binding paired box domain and nuclear localization signal of PAX5, but with C-terminal domains adopted from the fusion partners (7) ( Figure 2 ). A variety of partner genes, including transcription factors, structural proteins, and signal transducers, have been identified to fuse with the PAX5 gene (7, 16).

Figure 2.

PAX5 rearrangements in B-ALL. The summary of PAX5 rearrangements is based on the result from the 1,988 B-ALL cohort (16). (A) Distribution of PAX5 fusion partners. The fusion partners observed in at least 2 B-ALL cases are annotated in the pie chart, and the singletons are merged into the “other” group. (B) Scheme of PAX5 rearrangements with recurrent partner genes. The most common isoform of each fusion is shown. The green bars indicate the remaining part of the PAX5 protein. The starting amino acid (aa) of the fusion partners are annotated in parentheses. All the rearrangements reserve the paired box DNA binding domain of PAX5, except the fusions with ZCCHC7, a proximal gene commonly fused with PAX5 by focal deletion.

With the intact paired domain, these fusion proteins are thought to bind DNA and act as dominant-negative proteins to interfere the wild-type (WT) PAX5 activities (1, 52–54). Notably, PAX5 protein consisting of only the paired domain cannot compete with full-length PAX5 for DNA binding in vivo (55), suggesting that the C terminal of PAX5 may contribute to DNA binding through unknown mechanisms. Indeed, PAX5 fusions with different partners display distinct DNA binding and gene regulation activities which should be examined case by case (56). In general, transient reporter assays revealed that PAX5 fusions functioned as a dominant-negative regulator for WT PAX5 through binding to PAX5-target sequences (5, 52). Some of the fusions, such as PAX5::C20S and PAX5::ETV6, showed stable DNA binding activity through forming oligomers due to the presence of oligomerization domains of the fusion partners (54, 56). As one exception, PAX5::PML barely showed DNA-binding activity but interfered with PAX5 regulatory activity through association with PAX5 proteins (53).

In contrast to deletions, PAX5 fusions are commonly observed in leukemic cells displaying a relatively normal karyotype, indicating that they are founder lesions in leukemogenesis (9). In addition, PAX5 fusions, except PAX5::JAK2 and PAX5::ZCCHC7, are observed in over 30% of PAX5alt B-ALL, a recently reported subtype defined by various PAX5 alterations and a distinct gene expression profile (16). Consistently, PAX5 rearranged with ETV6, ELN, and PML were verified to be the primary oncogenic drivers in transgenic mice (55, 57, 58). PAX5::ETV6, the most recurrent PAX5 fusion in B-ALL, contains three domains that contribute to DNA binding behavior, which are the paired box and helix-loop-helix domain of PAX5, and the DNA binding domain of ETV6 (16, 56, 59, 60). PAX5::ETV6 regulates 68% of PAX5-target genes in an opposing manner when transduced into murine B cells. This opposite dominant effect might be responsible for impaired B cell development (61). When knocked-in into the mouse Pax5 locus, PAX5::ETV6 blocked B cell development at the pro-B to pre-B transition but was insufficient to promote leukemogenesis (55). However, when crossed with Cdkn2a/b deletion mice, B-lineage leukemia was developed at full penetrance with frequent loss of the remaining WT Cdkn2a/b allele (55). Comparing to PAX5::ETV6, PAX5::ELN acts as a more potent initiating event to induce leukemia, with frequent acquisition of secondary mutations in Ptpn11, Jak3, and Kras genes in mice (58). Different from the transient expression in vitro, the PAX5 fusions expressed in murine models do not generally antagonize the WT PAX5 function but activate independent biological pathways to establish the molecular basis required for leukemic transformation (55, 58). This discrepancy may be explained by either different protein levels or distinct regulatory mechanisms between transient and in vivo expressed proteins (58).

PAX5::JAK2 rearrangement exerts a distinct gene expression signature in B-ALL and is exclusively found in the Ph-like subtype (16, 62). It consists of the paired domain of PAX5 and the kinase domain of JAK2 (7). In contrast to cytoplasmatic localization of other JAK2 fusions such as BCR::JAK2 and ETV6::JAK2, PAX5::JAK2 protein is localized in nucleus and binds the PAX5 targets (62). It simultaneously deregulates PAX5-target genes while activating JAK/STAT signaling in the nucleus (62). In a constitutive knock-in mouse model, PAX5::JAK2 rapidly induced aggressive B-ALL without acquisition of other cooperating mutations (63), which unequivocally implicated that PAX5::JAK2 functions as dual hits, which are PAX5 haploinsufficiency and constitutively active kinase activity, to drive leukemogenesis (63).

There’s a rare translocation that does not produce chimeric protein but juxtaposes the IGH Eµ enhancer to proximity of the PAX5 promoter, leading to dysregulation of PAX5 expression. This translocation is found in a subset of B cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma cases (64, 65). When reconstructed by insertion of a PAX5 mini gene into the mouse Igh locus, these mice develop aggressive T-lymphoblastic lymphomas instead of B-ALL, probably because of the expression of PAX5 throughout the lymphoid system as a germline mutation rather than as somatic mutations in patients (66). It also reflects the potential caveats of using mouse models to mimic the B-lineage malignancies induced by PAX5 alterations (67).

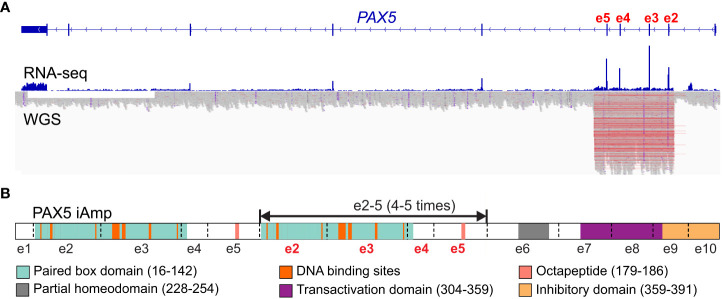

Intragenic amplification (iAmp)

PAX5 intragenic amplifications (PAX5-iAmp) were reported in different B-ALL cohorts at an incidence of 0.5-1.4% (1, 15–17, 68). B-ALL cases with PAX5-iAmp lacked stratifying genetic markers and were mutually exclusive from other risk-stratifying alterations (12, 15). Transcriptome sequencing (RNA-seq) revealed that they formed a tight cluster in unsupervised hierarchical cluster analysis (17) and can be grouped into the PAX5alt subtype (16). Interestingly, PAX5-iAmp frequently harbor CDKN2A/B homozygous loss and trisomy 5 (15, 17). The preservation of PAX5-iAmp in matched diagnosis and relapse samples, as well as GEP clustering in the PAX5alt subtype, indicates that it may act as a driver lesion in B-ALL (15, 16).

Whether PAX5-iAmp can encode structurally mutant PAX5 proteins or loss of function is still unknown. For most cases, the amplifications encompass exons 2 to 5, which encode the DNA-binding and octapeptide domains of PAX5 (15, 16, 68). Efforts have been taken to delineate the copy number of the amplified region, including chromosomal microarray analysis and multiplex ligation dependent probe amplification-based testing (15, 68). Recently, optical genomic mapping, a direct visualization method, has been applied to 3 PAX5-iAmp cases and found that they have an extra 4-5 copies of exons 2 to 5 inserted in situ in direct orientation (68) ( Figure 3 ). Considering the amplified paired domain by PAX5-iAmp, the increased copies of the DNA-binding region may alter the binding to PAX5-target genes, thus leading to dysregulated B cell differentiation and transformation. Further functional studies are still needed to address the specific role of PAX5-iAmp in B-ALL.

Figure 3.

Scheme of PAX5 intragenic amplification (PAX5 iAmp). (A) PAX5 iAmp detected by RNA-seq and whole genome sequencing (WGS (16)). The most frequently affected exons are e2-5, which are shown with increased expression levels (by RNA-seq) compared to the adjacent exons. The amplified region on the genomic level is reflected by abruptly elevated depth from WGS, which corroborates the affected exons identified from RNA-seq. (B) PAX5 iAmp leads to an extended isoform of PAX5. Using optical genomic mapping, 4-5 extra copies of PAX5 e2-5 were determined in the PAX5 iAmp cases. The tandem multiplication of PAX5 paired box DNA binding domain may change its binding activity, thus altering its transcription program and disrupting B cell differentiation (68).

Alternative splicing and different isoforms

Alternative splicing of PAX5 gene has been found during normal B cells development. By using two distinct promoters, PAX5 can generate two different isoforms (PAX5A and PAX5B) that share the same exons 2-10 but with different exon 1 encoding N-terminal 15 or 14 amino acids, respectively (64). Pax5A is exclusively expressed in B cells, while Pax5B is active in all Pax5-expressing tissues such as the nervous system, testis, and B-lineage cells (64). In humans, five additional alternative isoforms have been detected in normal human B cells generated by the exclusion of exons 7, 8 and/or 9, which encode the C-terminal transactivation domain (69). The ability to induce CD19-promoter-based reporter expression by various isoforms was significantly influenced by the changes in the C-terminal domain (69). In mouse models, three additional isoforms of Pax5 due to alternative splicing have been detected during B cells development. These isoforms arise from the exclusion of exon 2 and/or 3’ region, encoding proteins lacking part of the DNA-binding and/or the transcriptional regulatory domains, which are assumed to participate in stage-specific regulation of B cell maturation (70).

In multiple myeloma, a plasma cell disorder, diverse PAX5 isoforms have been identified accompanied with low levels of the WT PAX5 expression (71). These noncanonical isoforms are incapable of generating functional PAX5 proteins, which may drive proliferating B cells to prematurely differentiate into plasma cells (71). In B-ALL, alternative PAX5 isoforms missing exon 2, exons 8-9, or exon 5 have been reported (72, 73). However, considering the frequent PAX5 intragenic deletions in B-ALL (1, 16), some of the alternative isoforms found in B-ALL might be attributed to focal deletions instead of alternative splicing.

Point mutations

Point mutations are the second most common PAX5 variants observed in B-ALL (7%~10%) (1, 6, 8). In 203 nonsilent PAX5 mutations identified from 1,988 B-ALL cases (16), around three quarters are missense mutations enriched in the DNA-binding domain and are predicted to impair DNA binding by structural modelling, whereas disruptive mutations such as frameshift and nonsense are often found in the transcriptional regulatory domain (1, 16). The paired domain is a bipartite DNA-binding domain consisting of two subdomains (NTD and CTD). Each subdomain contains a helix-turn-helix motif which binds to major grooves of the DNA helix contributing to the overall binding affinity (74). Although both contribute to DNA binding, NTD determines the specificity of binding with its affinity 10 times higher than the CTD (75, 76). Coincidentally, mutations within the paired domain tend to enrich in NTD compared to CTD (52.7% to 10.3%, respectively) (16). Supporting the prevalence and importance of paired domain mutations, a study used chemical and retroviral strategies to induce random mutagenesis in Pax5 +/ - mice. For the 13 induced Pax5 mutations acting as cooperating lesions for B-ALL, 12 are in the paired domain (67).

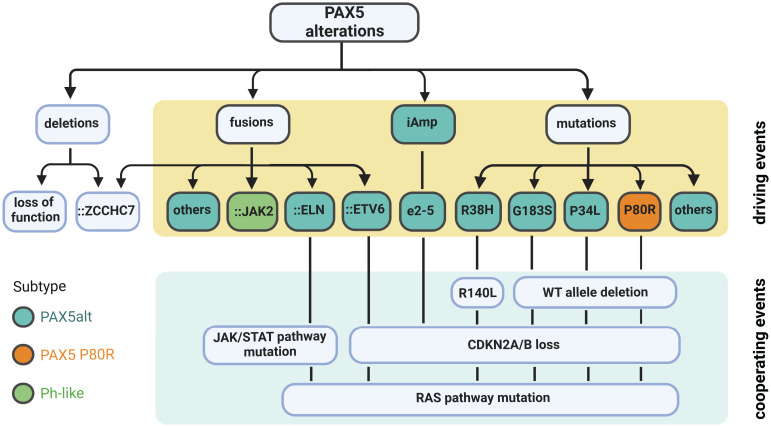

PAX5 P80R, a substitution located in the paired domain, was identified as the most frequent sequence mutation of PAX5 (1, 6, 8). B-ALL patients with the PAX5 P80R mutation are classified as a novel subtype defined by this missense mutation and a highly distinct GEP (16, 77). This subtype is characterized by biallelic alterations of PAX5, homozygous deletion of CDKN2A/B, and hotspot activating mutations of RAS signaling ( Figure 4 ) (16, 18). The biallelic alterations of PAX5 are achieved by deletions, copy-neutral loss of heterozygosity, or deleterious mutations on the other allele of PAX5 (16). Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) revealed dysregulation of B-cell-specific genes, suggesting that PAX5 P80R decreases the regulatory activity of PAX5 (16), probably through altering its DNA binding pattern (1). Consistently, PAX5 P80R blasts were arrested at the pre-pro-B stage (16), with T-cell antigen CD2 expressed in half of the patients (78). PAX5 P80R B-ALL subtype, together with DUX4r and ZNF384r subtypes, frequently undergo monocytic switch (79). The patients of this subtype were reported with various levels of risk in different cohorts (16, 18, 19, 80). Therefore, further evaluation of the clinical significance of this novel subtype is still needed. The oncogenic role of PAX5 P80R has been demonstrated using constitutive knock-in mouse models. Both homozygous and heterozygous Pax5 P80R transgenic mice developed B-lineage leukemia with almost complete penetrance. Analysis of mouse leukemia from the Pax5 P80R heterozygous mice revealed the disruption of the remaining Pax5 WT allele by deletion or frameshift mutations, which recapitulated the loss of PAX5 WT allele in patient samples (16).

Figure 4.

Summary of PAX5 alterations in B-ALL. Deletion is the most common type of PAX5 alteration in B-ALL, but generally considered as a secondary driver event. Focal deletion can lead to the concatenation of PAX5 to its adjacent gene ZCCHC7, a genetic lesion frequently observed in Ph-like and other B-ALL subtypes. PAX5 fusions, iAmp (most commonly targeting exon 2 to 5 (e2-5)), and point mutations are highly enriched in the PAX5alt subtype (16). PAX5 fusions and iAmp of e2-5 driven B-ALL harbor biallelic CDKN2A/B loss and RAS or JAK/STAT pathway mutations (16, 55, 58). PAX5::JAK2, a signature fusion of the Ph-like subtype, can act as a dual hit for B-ALL without cooperating lesions (63). PAX5-mutation-driven cases normally have deletion of the remaining WT allele and total loss of CDKN2A/B. They also frequently acquire mutations in the RAS signaling pathway. PAX5 P80R mutation defines an independently subtype with a distinct GEP (16).

Non-silent PAX5 mutations are observed in over 30% of the PAX5alt group compared to less than 5% of the other B-ALL cases (16). Over 40% of PAX5 mutations within PAX5alt subtype are hemizygous due to loss of the PAX5 WT allele. The two most recurrent mutations enriched in this subtype are R38H and R140L, which are located in the NTD and CTD of the DNA binding domain, respectively. Notably, 10 of 11 R140L mutations were found co-occurrent with R38H in the same patients (16). RNA-seq of one familial B-ALL case observed that these two mutations were detected on different alleles (20). PAX5alt cases with PAX5 mutations (except R38H and R140L) are commonly observed with loss of the remaining PAX5 WT allele and total deletion of CDKN2A/B genes. They are also enriched with RAS signaling pathway mutations as cooperating events ( Figure 4 ) (16). Besides PAX5 mutations, PAX5 rearrangements and intragenic amplifications were also reported as signature genetic lesions of the PAX5alt group (16). The prognosis of this subtype is significantly worse than PAX5 P80R (16), especially in adult cases (78). Within the PAX5alt subtype, patients with IKZF1 deletions were observed with even worse prognosis (81). In conclusion, the large collection of PAX5 point mutations in B-ALL with unique gene expression features implies that besides P80R, certain PAX5 mutations may also act as initiating driver events. Further direct experimental evidence is needed to test this hypothesis.

Germline variants and B-ALL susceptibility

PAX5 germline variants have been identified in multiple familial B-ALL studies. Although rare, the existence of certain familial B-ALL cases provided compelling evidence that PAX5 germline variants can induce B-ALL. The first evidence came from a heterozygous germline variant PAX5 G183S, affecting the octapeptide domain of PAX5, found in three unrelated B-ALL kindreds with incomplete penetrance (11) (13). All affected cases exhibited chromosome 9p deletion that removed the PAX5 WT allele and caused homozygous deletion of CDKN2A/B ( Figure 4 ). Functional and gene expression analysis of the PAX5 G183S mutation demonstrated that it significantly reduced transcriptional activity of PAX5 (11). The finding of PAX5 WT allele deletion in PAX5 G183S cases suggests that a complete disruption of WT PAX5 is essential for B cell developmental arrest mediated by G183S (11, 13).

Further evidence came from another family with a high incidence of B-ALL affecting all three children, which harbored a PAX5 R38H germline variant (20). This variant was inherited from one of the parents who didn’t develop leukemia, suggesting that additional lesions are required for full transformation. Consistently, all affected children gained mutations in the remaining PAX5 WT allele. Specifically, two of them independently developed R140L mutation, which is commonly concomitant with R38H in sporadic B-ALL, while the remaining one had a PAX5 frameshift mutation at Y371. In addition, all three children had CDKN2A/B homozygous loss and RAS signaling pathway mutations ( Figure 4 ) (20). When transduced into murine Pax5 -/- cells, PAX5 R38H failed to regulate PAX5-target genes, suggesting that R38H impaired normal PAX5 function (20). Comparing to PAX5 G183S germline variant, PAX5 R38H is associated with an older onset, but both shared the feature of disrupting the PAX5 WT allele and CDKN2A/B genes (11, 13, 20). Taken together, these findings strengthen the conclusion that PAX5 germline variants can confer strong B-ALL susceptibility and are associated with specific additional genetic lesions to initiate overt B-ALL.

Therapeutic potential of PAX5 alterations

As the most frequent genetic lesions in B-ALL, PAX5 alterations have been demonstrated to impair B cell differentiation and give rise to overt leukemia with the acquisition of cooperating genetic lesions. In addition, ongoing PAX5 deficiency is required for maintaining the lymphoblastic status of the malignant B cells in vivo (82). Based on these findings, strategies such as re-activating the differentiation potential of the malignant B cells to circumvent the developmental blockage may provide new therapeutic entry points. Indeed, restoring Pax5 through Tet-Off the transgenic shPax5 in a mouse B-ALL model (driven by Pax5 knockdown and constitutively active Stat5) enables differentiation and immunophenotypic maturation by reshaping the B cell development program, leading to durable disease remission (82). Remarkably, even brief Pax5 restoration in B-ALL cells causes rapid cell cycle exit and disables their leukemia-initiating capacity (82). In addition, reconstitution of PAX5 in B-ALL patient samples carrying PAX5 deletions can restore an energy nonpermissive state, leading to energy crisis and cell death (23). Interestingly, forced expression of PAX2 or PAX8, the two most closely related paralogs of PAX5, resulted in growth inhibition of the REH cell line, which carries a heterozygous PAX5 A322fs frameshift mutation. These two paralogs complement the haploinsufficiency of PAX5 in B-ALL cells by modulating PAX5-target genes and restoring B cell differentiation (83). Therefore, approaches that can by-pass the differentiation blockage resulting from PAX5 haploinsufficiency may lead to novel therapeutic approaches for this group of B-ALL, including but not limited to PAX5 restoration and PAX5 paralog activation.

The deregulated networks triggered by PAX5 variants may offer other therapeutic strategies as well. For example, PAX5 deficiency can lead to upregulated metabolic genes and consequently increased glucose uptake and energy metabolism, which are essential for leukemic transformation (23, 49). Specifically, glucocorticoid receptor NR3C1, glucose-feedback sensor TXNIP, and cannabinoid receptor CNR2 were identified as central effectors of energy supply restriction in B cells. In addition, agonists against CNR2 and TXNIP synergized with glucocorticoids to exacerbate B-cell-intrinsic ATP depletion and restored the energy barrier against B-cell malignancy (23). Furthermore, Pax5 heterozygosis can enhance the expression of inflammatory cytokine interleukin−6 (IL−6), which then promote proliferation of leukemia cells. Genetic down-regulation or pharmacologic inhibition of IL−6 is beneficial to leukemic cell clearance (84). In addition, as mentioned above, PAX5-variant-related leukemia is commonly associated with aberrant activation of the kinase pathways such as JAK/STAT and RAS signaling. On one hand, treatment with kinase inhibitors resulted in increased apoptosis of leukemic cells (50, 85). On the other hand, considering the requirement of converging genetic lesions into one principal pathway for leukemia initiation, pharmacological reactivation of suppressed divergent pathways may also provide a powerful barrier to leukemic transformation (86). Finally, since the majority of B-ALL subtypes are observed with distinct GEPs, the subtype-specific biomarkers may serve as targets for developing tailored therapies. Notably, the MEGF10 gene was exclusively overexpressed in the PAX5 P80R B-ALL subtype, which may serve as a biomarker as well as a potential therapeutic target for this subtype (16).

Discussion

Recent genomic and transcriptomic analysis of B-ALL has largely advanced our understanding of PAX5 and its altered isoforms in regulating normal B cell development and driving malignant transformation ( Table 1 ). It has been demonstrated that genetic alterations of PAX5 in B-ALL commonly lead to a reduction in rather than a total loss of PAX5 activity. These observations suggest that a certain level of PAX5 activity is required in B-ALL to maintain B cell identity and sustain clonal expansion but is insufficient to execute normal B cell differentiation. Therefore, the remaining PAX5 WT allele must be ablated by either deletions or deleterious mutations to achieve this haploinsufficiency threshold. The process of acquiring additional genetic lesions in PAX5-altered B-ALL and the underlying mechanisms are intriguing but still largely unknown. The mechanisms of V(D)J recombination, as well as class-switch recombination and somatic hypermutation in B cell development might be exploited to generate these oncogenic lesions.

In-depth investigation of the oncogenic roles of germline and somatic PAX5 variants is still largely unavailable. Reconstruction of genetic lesions in mouse models to recapitulate the corresponding human disease is widely applied to approach this goal. However, cautions should be taken considering the potential phenotypical discrepancies between human diseases and mouse models. For example, the Igh::Pax5 mice develop T-ALL instead of B-ALL observed in patients, which might be attributed to the germline nature of the fusion gene in mice (66). Moreover, the Pax5::Jak2 mouse model generates a more aggressive leukemia through loss of the Pax5 WT allele caused by uniparental disomy of the Pax5::Jak2 allele, but the PAX5 WT allele is normally retained in human PAX5::JAK2 leukemia (63). Finally, Pax5 G183S is insufficient for malignant transformation in a transgenic mouse model (16), although it has been found as a germline variant associated with strong susceptibility to human B-ALL (11, 13). Nonetheless, mouse models still play a critical role for investigating the function of PAX5 variants in leukemic transformation.

In summary, genome-wide technologies have greatly refined the molecular diagnosis of B-ALL, at the same time leading to the discovery of diverse PAX5 alterations as primary or secondary events in B cell transformation. In conjunction with the advanced understanding of PAX5 in B cell development, it will provide an objective basis for a better diagnosis and treatment of B-ALL.

Author contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Funding

This work was supported by the Research Start-Up Budget from the Beckman Research Institute of the City of Hope (to ZG), the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society Special Fellow Award LLS-3381-19 (to ZG) and NIH/NCI Pathway to Independence Award R00 CA241297 (to ZG).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- 1. Mullighan CG, Goorha S, Radtke I, Miller CB, Coustan-Smith E, Dalton JD, et al. Genome-wide analysis of genetic alterations in acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Nature (2007) 446(7137):758–64. doi: 10.1038/nature05690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kuiper RP, Schoenmakers EF, van Reijmersdal SV, Hehir-Kwa JY, van Kessel AG, van Leeuwen FN, et al. High-resolution genomic profiling of childhood ALL reveals novel recurrent genetic lesions affecting pathways involved in lymphocyte differentiation and cell cycle progression. Leukemia (2007) 21(6):1258–66. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mullighan CG, Miller CB, Radtke I, Phillips LA, Dalton J, Ma J, et al. BCR-ABL1 lymphoblastic leukaemia is characterized by the deletion of ikaros. Nature (2008) 453(7191):110–4. doi: 10.1038/nature06866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mullighan CG, Phillips LA, Su X, Ma J, Miller CB, Shurtleff SA, et al. Genomic analysis of the clonal origins of relapsed acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Science (2008) 322(5906):1377–80. doi: 10.1126/science.1164266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kawamata N, Ogawa S, Zimmermann M, Niebuhr B, Stocking C, Sanada M, et al. Cloning of genes involved in chromosomal translocations by high-resolution single nucleotide polymorphism genomic microarray. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. (2008) 105(33):11921–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711039105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mullighan CG, Su X, Zhang J, Radtke I, Phillips LA, Miller CB, et al. Deletion of IKZF1 and prognosis in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. N Engl J Med (2009) 360(5):470–80. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808253 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nebral K, Denk D, Attarbaschi A, Konig M, Mann G, Haas OA, et al. Incidence and diversity of PAX5 fusion genes in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia (2009) 23(1):134–43. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Familiades J, Bousquet M, Lafage-Pochitaloff M, Bene MC, Beldjord K, De Vos J, et al. PAX5 mutations occur frequently in adult b-cell progenitor acute lymphoblastic leukemia and PAX5 haploinsufficiency is associated with BCR-ABL1 and TCF3-PBX1 fusion genes: a GRAALL study. Leukemia (2009) 23(11):1989–98. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Coyaud E, Struski S, Prade N, Familiades J, Eichner R, Quelen C, et al. Wide diversity of PAX5 alterations in b-ALL: a groupe francophone de cytogenetique hematologique study. Blood (2010) 115(15):3089–97. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-07-234229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Iacobucci I, Lonetti A, Paoloni F, Papayannidis C, Ferrari A, Storlazzi CT, et al. The PAX5 gene is frequently rearranged in BCR-ABL1-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia but is not associated with outcome. a report on behalf of the GIMEMA acute leukemia working party. Haematologica (2010) 95(10):1683–90. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2009.020792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Shah S, Schrader KA, Waanders E, Timms AE, Vijai J, Miething C, et al. A recurrent germline PAX5 mutation confers susceptibility to pre-b cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Nat Genet (2013) 45(10):1226–31. doi: 10.1038/ng.2754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ofverholm I, Tran AN, Heyman M, Zachariadis V, Nordenskjold M, Nordgren A, et al. Impact of IKZF1 deletions and PAX5 amplifications in pediatric b-cell precursor ALL treated according to NOPHO protocols. Leukemia (2013) 27(9):1936–9. doi: 10.1038/leu.2013.92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Auer F, Ruschendorf F, Gombert M, Husemann P, Ginzel S, Izraeli S, et al. Inherited susceptibility to pre b-ALL caused by germline transmission of PAX5 c.547G>A. Leukemia (2014) 28(5):1136–8. doi: 10.1038/leu.2013.363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Roberts KG, Gu Z, Payne-Turner D, McCastlain K, Harvey RC, Chen IM, et al. High frequency and poor outcome of Philadelphia chromosome-like acute lymphoblastic leukemia in adults. J Clin Oncol (2017) 35(4):394–401. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.69.0073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Schwab C, Nebral K, Chilton L, Leschi C, Waanders E, Boer JM, et al. Intragenic amplification of PAX5: a novel subgroup in b-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia? Blood Adv (2017) 1(19):1473–7. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2017006734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gu Z, Churchman ML, Roberts KG, Moore I, Zhou X, Nakitandwe J, et al. PAX5-driven subtypes of b-progenitor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Nat Genet (2019) 51(2):296–307. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0315-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zaliova M, Stuchly J, Winkowska L, Musilova A, Fiser K, Slamova M, et al. Genomic landscape of pediatric b-other acute lymphoblastic leukemia in a consecutive European cohort. Haematologica (2019) 104(7):1396–406. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2018.204974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bastian L, Schroeder MP, Eckert C, Schlee C, Tanchez JO, Kampf S, et al. PAX5 biallelic genomic alterations define a novel subgroup of b-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia (2019) 33(8):1895–909. doi: 10.1038/s41375-019-0430-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jung M, Schieck M, Hofmann W, Tauscher M, Lentes J, Bergmann A, et al. Frequency and prognostic impact of PAX5 p.P80R in pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia patients treated on an AIEOP-BFM acute lymphoblastic leukemia protocol. Genes Chromosomes Cancer (2020) 59(11):667–71. doi: 10.1002/gcc.22882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Duployez N, Jamrog LA, Fregona V, Hamelle C, Fenwarth L, Lejeune S, et al. Germline PAX5 mutation predisposes to familial b-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood (2021) 137(10):1424–8. doi: 10.1182/blood.2020005756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Liu X, Chen JG, Munshi M, Hunter ZR, Xu L, Kofides A, et al. Expression of the prosurvival kinase HCK requires PAX5 and mutated MYD88 signaling in MYD88-driven b-cell lymphomas. Blood Adv (2020) 4(1):141–53. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2019000947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Calderon L, Schindler K, Malin SG, Schebesta A, Sun Q, Schwickert T, et al. Pax5 regulates b cell immunity by promoting PI3K signaling via PTEN down-regulation. Sci Immunol (2021) 6(61). doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.abg5003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chan LN, Chen Z, Braas D, Lee JW, Xiao G, Geng H, et al. Metabolic gatekeeper function of b-lymphoid transcription factors. Nature (2017) 542(7642):479–83. doi: 10.1038/nature21076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Somasundaram R, Jensen CT, Tingvall-Gustafsson J, Ahsberg J, Okuyama K, Prasad M, et al. EBF1 and PAX5 control pro-b cell expansion via opposing regulation of the myc gene. Blood (2021) 137(22):3037–49. doi: 10.1182/blood.2020009564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ramamoorthy S, Kometani K, Herman JS, Bayer M, Boller S, Edwards-Hicks J, et al. EBF1 and Pax5 safeguard leukemic transformation by limiting IL-7 signaling, myc expression, and folate metabolism. Genes Dev (2020) 34(21-22):1503–19. doi: 10.1101/gad.340216.120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hill L, Ebert A, Jaritz M, Wutz G, Nagasaka K, Tagoh H, et al. Wapl repression by Pax5 promotes V gene recombination by igh loop extrusion. Nature (2020) 584(7819):142–7. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2454-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Barberis A, Widenhorn K, Vitelli L, Busslinger M. A novel b-cell lineage-specific transcription factor present at early but not late stages of differentiation. Genes Dev (1990) 4(5):849–59. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.5.849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Simmons S, Knoll M, Drewell C, Wolf I, Mollenkopf HJ, Bouquet C, et al. Biphenotypic b-lymphoid/myeloid cells expressing low levels of Pax5: potential targets of BAL development. Blood (2012) 120(18):3688–98. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-03-414821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lin KI, Angelin-Duclos C, Kuo TC, Calame K. Blimp-1-dependent repression of pax-5 is required for differentiation of b cells to immunoglobulin m-secreting plasma cells. Mol Cell Biol (2002) 22(13):4771–80. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.13.4771-4780.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Liu GJ, Jaritz M, Wohner M, Agerer B, Bergthaler A, Malin SG, et al. Repression of the b cell identity factor Pax5 is not required for plasma cell development. J Exp Med (2020) 217(11). doi: 10.1084/jem.20200147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Urbanek P, Wang ZQ, Fetka I, Wagner EF, Busslinger M. Complete block of early b cell differentiation and altered patterning of the posterior midbrain in mice lacking Pax5/BSAP. Cell (1994) 79(5):901–12. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90079-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Nutt SL, Heavey B, Rolink AG, Busslinger M. Commitment to the b-lymphoid lineage depends on the transcription factor Pax5. Nature (1999) 401(6753):556–62. doi: 10.1038/44076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rolink AG, Nutt SL, Melchers F, Busslinger M. Long-term in vivo reconstitution of T-cell development by Pax5-deficient b-cell progenitors. Nature (1999) 401(6753):603–6. doi: 10.1038/44164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mikkola I, Heavey B, Horcher M, Busslinger M. Reversion of b cell commitment upon loss of Pax5 expression. Science (2002) 297(5578):110–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1067518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Horcher M, Souabni A, Busslinger M. Pax5/BSAP maintains the identity of b cells in late b lymphopoiesis. Immunity (2001) 14(6):779–90. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(01)00153-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Schebesta A, McManus S, Salvagiotto G, Delogu A, Busslinger GA, Busslinger M. Transcription factor Pax5 activates the chromatin of key genes involved in b cell signaling, adhesion, migration, and immune function. Immunity (2007) 27(1):49–63. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.05.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Delogu A, Schebesta A, Sun Q, Aschenbrenner K, Perlot T, Busslinger M. Gene repression by Pax5 in b cells is essential for blood cell homeostasis and is reversed in plasma cells. Immunity (2006) 24(3):269–81. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. McManus S, Ebert A, Salvagiotto G, Medvedovic J, Sun Q, Tamir I, et al. The transcription factor Pax5 regulates its target genes by recruiting chromatin-modifying proteins in committed b cells. EMBO J (2011) 30(12):2388–404. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Cobaleda C, Schebesta A, Delogu A, Busslinger M. Pax5: the guardian of b cell identity and function. Nat Immunol (2007) 8(5):463–70. doi: 10.1038/ni1454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Okuyama K, Strid T, Kuruvilla J, Somasundaram R, Cristobal S, Smith E, et al. PAX5 is part of a functional transcription factor network targeted in lymphoid leukemia. PloS Genet (2019) 15(8):e1008280. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1008280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Decker T, Pasca di Magliano M, McManus S, Sun Q, Bonifer C, Tagoh H, et al. Stepwise activation of enhancer and promoter regions of the b cell commitment gene Pax5 in early lymphopoiesis. Immunity (2009) 30(4):508–20. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Roessler S, Gyory I, Imhof S, Spivakov M, Williams RR, Busslinger M, et al. Distinct promoters mediate the regulation of Ebf1 gene expression by interleukin-7 and Pax5. Mol Cell Biol (2007) 27(2):579–94. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01192-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Nutt SL, Urbanek P, Rolink A, Busslinger M. Essential functions of Pax5 (BSAP) in pro-b cell development: Difference between fetal and adult b lymphopoiesis and reduced V-to-DJ recombination at the IgH locus. Genes Dev (1997) 11(4):476–91. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.4.476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hesslein DG, Pflugh DL, Chowdhury D, Bothwell AL, Sen R, Schatz DG. Pax5 is required for recombination of transcribed, acetylated, 5’ IgH V gene segments. Genes Dev (2003) 17(1):37–42. doi: 10.1101/gad.1031403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Fuxa M, Skok J, Souabni A, Salvagiotto G, Roldan E, Busslinger M. Pax5 induces V-to-DJ rearrangements and locus contraction of the immunoglobulin heavy-chain gene. Genes Dev (2004) 18(4):411–22. doi: 10.1101/gad.291504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kim M, Choi JE, She CJ, Hwang SM, Shin HY, Ahn HS, et al. PAX5 deletion is common and concurrently occurs with CDKN2A deletion in b-lineage acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood Cells Mol Dis (2011) 47(1):62–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2011.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Heltemes-Harris LM, Willette MJ, Ramsey LB, Qiu YH, Neeley ES, Zhang N, et al. Ebf1 or Pax5 haploinsufficiency synergizes with STAT5 activation to initiate acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Exp Med (2011) 208(6):1135–49. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Prasad MA, Ungerback J, Ahsberg J, Somasundaram R, Strid T, Larsson M, et al. Ebf1 heterozygosity results in increased DNA damage in pro-b cells and their synergistic transformation by Pax5 haploinsufficiency. Blood (2015) 125(26):4052–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-12-617282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Martin-Lorenzo A, Auer F, Chan LN, Garcia-Ramirez I, Gonzalez-Herrero I, Rodriguez-Hernandez G, et al. Loss of Pax5 exploits Sca1-BCR-ABL(p190) susceptibility to confer the metabolic shift essential for pB-ALL. Cancer Res (2018) 78(10):2669–79. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-3262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Martin-Lorenzo A, Hauer J, Vicente-Duenas C, Auer F, Gonzalez-Herrero I, Garcia-Ramirez I, et al. Infection exposure is a causal factor in b-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia as a result of Pax5-inherited susceptibility. Cancer Discovery (2015) 5(12):1328–43. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-0892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Cobaleda C, Jochum W, Busslinger M. Conversion of mature b cells into T cells by dedifferentiation to uncommitted progenitors. Nature (2007) 449(7161):473–7. doi: 10.1038/nature06159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Bousquet M, Broccardo C, Quelen C, Meggetto F, Kuhlein E, Delsol G, et al. A novel PAX5-ELN fusion protein identified in b-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia acts as a dominant negative on wild-type PAX5. Blood (2007) 109(8):3417–23. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-025221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Kurahashi S, Hayakawa F, Miyata Y, Yasuda T, Minami Y, Tsuzuki S, et al. PAX5-PML acts as a dual dominant-negative form of both PAX5 and PML. Oncogene (2011) 30(15):1822–30. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Kawamata N, Pennella MA, Woo JL, Berk AJ, Koeffler HP. Dominant-negative mechanism of leukemogenic PAX5 fusions. Oncogene (2012) 31(8):966–77. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Smeenk L, Fischer M, Jurado S, Jaritz M, Azaryan A, Werner B, et al. Molecular role of the PAX5-ETV6 oncoprotein in promoting b-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. EMBO J (2017) 36(6):718–35. doi: 10.15252/embj.201695495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Fortschegger K, Anderl S, Denk D, Strehl S. Functional heterogeneity of PAX5 chimeras reveals insight for leukemia development. Mol Cancer Res (2014) 12(4):595–606. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-13-0337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Imoto N, Hayakawa F, Kurahashi S, Morishita T, Kojima Y, Yasuda T, et al. B cell linker protein (BLNK) is a selective target of repression by PAX5-PML protein in the differentiation block that leads to the development of acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Biol Chem (2016) 291(9):4723–31. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.637835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Jamrog L, Chemin G, Fregona V, Coster L, Pasquet M, Oudinet C, et al. PAX5-ELN oncoprotein promotes multistep b-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. (2018) 115(41):10357–62. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1721678115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Cazzaniga G, Daniotti M, Tosi S, Giudici G, Aloisi A, Pogliani E, et al. The paired box domain gene PAX5 is fused to ETV6/TEL in an acute lymphoblastic leukemia case. Cancer Res (2001) 61(12):4666–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Strehl S, Konig M, Dworzak MN, Kalwak K, Haas OA. PAX5/ETV6 fusion defines cytogenetic entity dic(9;12)(p13;p13). Leukemia (2003) 17(6):1121–3. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Fazio G, Cazzaniga V, Palmi C, Galbiati M, Giordan M, te Kronnie G, et al. PAX5/ETV6 alters the gene expression profile of precursor b cells with opposite dominant effect on endogenous PAX5. Leukemia (2013) 27(4):992–5. doi: 10.1038/leu.2012.281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Schinnerl D, Fortschegger K, Kauer M, Marchante JR, Kofler R, Den Boer ML, et al. The role of the janus-faced transcription factor PAX5-JAK2 in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood (2015) 125(8):1282–91. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-04-570960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Jurado S, Fedl AS, Jaritz M, Kostanova-Poliakova D, Malin SG, Mullighan CG, et al. The PAX5-JAK2 translocation acts as dual-hit mutation that promotes aggressive b-cell leukemia via nuclear STAT5 activation. EMBO J (2022) 41(7):e108397. doi: 10.15252/embj.2021108397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Busslinger M, Klix N, Pfeffer P, Graninger PG, Kozmik Z. Deregulation of PAX-5 by translocation of the emu enhancer of the IgH locus adjacent to two alternative PAX-5 promoters in a diffuse large-cell lymphoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. (1996) 93(12):6129–34. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.12.6129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Poppe B, De Paepe P, Michaux L, Dastugue N, Bastard C, Herens C, et al. PAX5/IGH rearrangement is a recurrent finding in a subset of aggressive b-NHL with complex chromosomal rearrangements. Genes Chromosomes Cancer (2005) 44(2):218–23. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Souabni A, Jochum W, Busslinger M. Oncogenic role of Pax5 in the T-lymphoid lineage upon ectopic expression from the immunoglobulin heavy-chain locus. Blood (2007) 109(1):281–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-03-009670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Dang J, Wei L, de Ridder J, Su X, Rust AG, Roberts KG, et al. PAX5 is a tumor suppressor in mouse mutagenesis models of acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood (2015) 125(23):3609–17. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-02-626127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Jean J, Kovach AE, Doan A, Oberley M, Ji J, Schmidt RJ, et al. Characterization of PAX5 intragenic tandem multiplication in pediatric b-lymphoblastic leukemia by optical genome mapping. Blood Adv (2022) 6(11):3343–6. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2021006328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Robichaud GA, Nardini M, Laflamme M, Cuperlovic-Culf M, Ouellette RJ. Human pax-5 c-terminal isoforms possess distinct transactivation properties and are differentially modulated in normal and malignant b cells. J Biol Chem (2004) 279(48):49956–63. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407171200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Zwollo P, Arrieta H, Ede K, Molinder K, Desiderio S, Pollock R. The pax-5 gene is alternatively spliced during b-cell development. J Biol Chem (1997) 272(15):10160–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.15.10160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Borson ND, Lacy MQ, Wettstein PJ. Altered mRNA expression of Pax5 and blimp-1 in b cells in multiple myeloma. Blood (2002) 100(13):4629–39. doi: 10.1182/blood.V100.13.4629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Sadakane Y, Zaitsu M, Nishi M, Sugita K, Mizutani S, Matsuzaki A, et al. Expression and production of aberrant PAX5 with deletion of exon 8 in b-lineage acute lymphoblastic leukaemia of children. Br J Haematol (2007) 136(2):297–300. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2006.06425.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Peinert S, Carney D, Prince HM, Januszewicz EH, Seymour JF. Altered mRNA expression of PAX5 is a common event in acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Br J Haematol (2009) 146(6):685–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07806.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Czerny T, Schaffner G, Busslinger M. DNA Sequence recognition by pax proteins: bipartite structure of the paired domain and its binding site. Genes Dev (1993) 7(10):2048–61. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.10.2048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Perez-Borrajero C, Okon M, McIntosh LP. Structural and dynamics studies of Pax5 reveal asymmetry in stability and DNA binding by the paired domain. J Mol Biol (2016) 428(11):2372–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2016.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Perez-Borrajero C, Heinkel F, Gsponer J, McIntosh LP. Conformational plasticity and DNA-binding specificity of the eukaryotic transcription factor Pax5. Biochemistry (2021) 60(2):104–17. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.0c00737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Li JF, Dai YT, Lilljebjorn H, Shen SH, Cui BW, Bai L, et al. Transcriptional landscape of b cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia based on an international study of 1,223 cases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. (2018) 115(50):E11711–20. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1814397115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Paietta E, Roberts KG, Wang V, Gu Z, Buck G, Pei D, et al. Molecular classification improves risk assessment in adult BCR-ABL1-negative b-ALL. Blood (2021) 138(11):948–58. doi: 10.1182/blood.2020010144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Novakova M, Zaliova M, Fiser K, Vakrmanova B, Slamova L, Musilova A, et al. DUX4r, ZNF384r and PAX5-P80R mutated b-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia frequently undergo monocytic switch. Haematologica (2020) 106(8):2066–75. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2020.250423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Passet M, Boissel N, Sigaux F, Saillard C, Bargetzi M, Ba I, et al. PAX5 P80R mutation identifies a novel subtype of b-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia with favorable outcome. Blood (2019) 133(3):280–4. doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-10-882142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Li Z, Lee SHR, Chin WHN, Lu Y, Jiang N, Lim EH, et al. Distinct clinical characteristics of DUX4- and PAX5-altered childhood b-lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood Adv (2021) 5(23):5226–38. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2021004895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Liu GJ, Cimmino L, Jude JG, Hu Y, Witkowski MT, McKenzie MD, et al. Pax5 loss imposes a reversible differentiation block in b-progenitor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Genes Dev (2014) 28(12):1337–50. doi: 10.1101/gad.240416.114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Hart MR, Anderson DJ, Porter CC, Neff T, Levin M, Horwitz MS. Activating PAX gene family paralogs to complement PAX5 leukemia driver mutations. PloS Genet (2018) 14(9):e1007642. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Isidro-Hernandez M, Mayado A, Casado-Garcia A, Martinez-Cano J, Palmi C, Fazio G, et al. Inhibition of inflammatory signaling in Pax5 mutant cells mitigates b-cell leukemogenesis. Sci Rep (2020) 10(1):19189. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-76206-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Cazzaniga V, Bugarin C, Bardini M, Giordan M, te Kronnie G, Basso G, et al. LCK over-expression drives STAT5 oncogenic signaling in PAX5 translocated BCP-ALL patients. Oncotarget (2015) 6(3):1569–81. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Chan LN, Murakami MA, Robinson ME, Caeser R, Sadras T, Lee J, et al. Signalling input from divergent pathways subverts b cell transformation. Nature (2020) 583(7818):845–51. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2513-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]