Abstract

In this comprehensive review, I focus on the twenty E. coli aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases and their ability to charge non-canonical amino acids (ncAAs) onto tRNAs. The promiscuity of these enzymes has been harnessed for diverse applications including understanding and engineering of protein function, creation of organisms with an expanded genetic code, and the synthesis of diverse peptide libraries for drug discovery. The review catalogs the structures of all known ncAA substrates for each of the 20 E. coli aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases, including ncAA substrates for engineered versions of these enzymes. Drawing from the structures in the list, I highlight trends and novel opportunities for further exploitation of these ncAAs in the engineering of protein function, synthetic biology, and in drug discovery.

Graphical Abstract

Surprising diversity: The aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases from E. coli have been extensively explored, and a surprising number of amino acid substrates have been described. This comprehensive review catalogs all known substrates for these enzymes and highlights trends and novel applications.

1. Introduction.

Researchers have long been interested in the tolerance of aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase (AARS) enzymes to non-canonical amino acid (ncAA) substrates. Decades ago, biochemists like Irving Boime, Paul Berg, and Leslie Fowden investigated AARS activation and protein expression in the presence of non-canonical amino acids[1–3]. Most of these early studies focused on the ability of AARS enzymes to activate naturally occurring ncAAs, often plant toxins. After the advent of modern molecular biology, this field has rapidly expanded, and now hundreds of ncAAs have been described as substrates. Although there are many reviews on AARS and ncAAs, most of these focus on stop codon suppression approaches that use the M. jannaschii tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase and the Methanosarcina barkeri or Methanosarcina masei pyrrolysyl-tRNA synthetases. Truly spectacular engineering feats have been accomplished with these enzymes[4,5]. Less focus has been given to the E. coli aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases and their tolerance towards ncAAs. Budisa[6,7], Schimmel,[8] and Montclare,[9] and have provided nice reviews here, but these are now somewhat old and there has been a significant investigation of these enzymes towards ncAAs in the intervening time. Many other recent reviews of the AARS enzymes have focused on their biology, structures, and their use in genetic code expansion[10–15]. In this comprehensive review, I focus specifically on the amino acid substrate specificity of wild-type and mutant E. coli AARS (ecAARS) towards ncAAs and their usefulness in translation.

The promiscuity ecAARS enzymes has been harnessed towards several applications (Fig. 1). The first, often termed selective pressure incorporation, involves global replacement of a certain amino acid in a protein with a ncAA (Fig. 1A)[7,16]. In this case, the ncAA or a precursor is added to the growth media of an auxotrophic strain of E. coli in the absence of the natural AA counterpart, prior to induction of protein expression. E. coli auxotrophs for most amino acids are available[17]. The proteins expressed in the presence of the ncAA often contain high percentages of the ncAA in place of the cognate AA; however, the high cellular concentrations of some canonical AA competitors can be an issue[18]. A few researchers have taken this a step further, adapting auxotrophic bacteria to tolerate incorporation of a ncAA throughout the proteome, through gradual replacement of the proteinogenic AA in the media with a ncAA analog (Fig. 1B)[19–21]. The evolved organisms can eventually survive on media containing only the ncAA[21]. EcAARS enzymes have also been used as orthogonal AARS/tRNA pairs introduced into other organisms (Fig 1C)[22–24]. To achieve this, an ecAARS and a compatible suppressor tRNA are introduced into a eukaryotic organism. The activation of the ncAA by that AARS will allow its sitespecific addition to a protein of interest in the living eukaryotic organism in response to a stop codon. Finally, the promiscuity of the ecAARS enzymes has been harnessed in in vitro selection technologies like mRNA display (Fig. 1D)[25–28]. In this case, the replacement of a proteinogenic AA with a ncAA enables the discovery of peptide ligands containing ncAAs from vast libraries[29].

Figure 1. Uses of ncAAs charged by E. coli AARS enzymes.

(A) Selective pressure incorporation enables protein expression wherein a single AA is substituted by a ncAA in every instance within an expressed protein. The temporary nature of the replacement reduces toxicity to the organism. (B) Permanent global replacement involves gradually allowing an organism to adapt to incorporation of a ncAA within its proteome—eventually the canonical AA can be withheld and replaced with the ncAA, leading to an organism with a permanently altered genetic code. (C) Site-selective incorporation involves incorporating an orthogonal AARS/stop codon suppressor tRNA pair from E. coli into another organism. Upon induction of expression, the ncAA can be incorporated selectively in response to a specific stop codon. (D) Peptide libraries with ncAAs can be developed by using reconstituted in vitro translation systems wherein multiple canonical AAs are withheld and replaced with ncAAs.

Here, I have compiled a comprehensive list of known substrates for ecAARS enzymes, with an emphasis on their usability in translation. For those that have been directly kinetically characterized as AARS substrates, a number of assays have been developed[30]. The most common assay used to test ncAA activation with AARSs is the pyrophosphate exchange assay[31,32] which measures only the formation of the aminoacyl-AMP intermediate, not the acylated tRNA. More recently, Wilson and Uhlenbeck developed an assay that involves using a tRNA labeled at the 3’-terminal internucleotide phosphate[33]. This assay has been adopted for the detection of ncAA-tRNA directly[25,26,34–36]. Hartman and Szostak also developed a MALDI assay useful for screening ncAAs for activation[25]. This assay has the advantage that multiple ncAAs can be screened simultaneously with the full collection of AARS enzymes, but is typically used qualitatively. Finally, many ncAAs that are ecAARS substrates have never been kinetically characterized as substrates[37] but have only been assessed indirectly, through monitoring of the incorporation of the AA into a peptide or protein via translation[38]. Those ncAAs tested in living cells (e.g. via selective pressure incorporation) not only have to be charged onto tRNA, but also must be taken up by the cells[37], metabolically stable, delivered as AA-tRNAs to the ribosome by EF-Tu, and able to serve as competent substrates for the ribosomal peptidyl transfer reaction.

Considering the disparate assays used to evaluate ecAARS substrates, direct comparisons are challenging. Most of the work in this field is driven by the desire to incorporate the ncAAs into proteins or peptides, it is therefore possible to broadly classify them based this ability as I have done in Table 1. Green dots represent good substrates for the translation apparatus. These are analogs that are proven or are likely to work in translation experiments in living E. coli. This designation also includes engineered E. coli AARS/ncAA pairs that are efficient for site-selective incorporation in eukaryotic organisms. Yellow dots indicate that there may be some challenges in translation with this AARS/ncAA pair when using it in living cells. This could be because the ncAA is a weak substrate for the AARS (some of these ncAAs have kcat/Km values >10,000-fold lower than the canonical AA[39]), or because there are high concentrations of the canonical AA competitor[18]. Alternatively, the AA may be only activated by a highly promiscuous mutant AARS that would not work for protein expression in cells due to competition from cognate AAs. These issues can often be solved in vitro by adding high concentrations of the ncAA and ecAARS and through thorough removal of residual canonical amino acid competitors. Finally, some ncAAs were given a yellow dot because they appear to be outliers based on their structure. These may be false positives, and further validation is recommended. Red dots denote analogs that are not currently compatible with translation; however, future engineering of the translation apparatus may enable incorporation. These rationales are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

ncAA classification system used in this review.

| Designation | Meaning | Reasons |

|---|---|---|

Green Dot |

Efficient charging and incorporation into proteins in living cells. |

|

Yellow Dot |

Potential issues with incorporation into proteins in living organisms, but likely to work in in vitro experiments. |

|

Red Dot |

Charged onto tRNA, but is not incorporated efficiently even in vitro. |

|

2. E. coli Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases and their substrates

2.1. Introduction.

In the following paragraphs, I describe all the known ecAARS substrates (as of Dec. 2020), discussing each of the 20 AARS enzymes individually. AsnRS and GlyRS are not included in the list as, to my knowledge, no ncAA substrates for these enzymes have been found.

2.2. AlaRS.

Due to its small binding pocket, very few ncAA substrates for AlaRS have been described (Fig. 2). EcAlaRS can charge 1-aminocyclopropanecarboxylic acid (A1), 1-aminocyclobutanecarboxylic acid (A2), and aminoisobutyric acid (Aib) (A3) onto tRNA as shown using a MALDI assay[25]. Of the three, A1 is the best substrate for AlaRS, but all 3 are difficult substrates for the translation apparatus. Provided efficiency can be improved, one could use the unique conformational properties of these amino acids to probe peptide and protein structure.

Figure 2.

ncAA substrates for ecAlaRS, ecArgRS and ecAspRS.

2.3. ArgRS.

L-canavanine (R1), is a toxic plant metabolite that is an efficient Arg analog with a surprisingly low pKa (7.0)[6,40]. Its toxicity is mediated through protein incorporation[41], and it is an efficient substrate E. coli ArgRS[42,43] (Fig. 2). A few additional analogs have been described. ArgRS also tolerates methylation (R2) and hydroxylation (R3) at the terminal nitrogen[25]. One amidine analog, vinyl-L-NIO, R4, has also been described[25]. R4 is well-known as an inhibitor of nitric oxide synthases[44].

2.4. AspRS.

Three ecAspRS substrates have been described by Hartman and Szostak[25] (Fig. 2). L-threo-3-hydroxyaspartic acid (D1) is an excellent substrate. D1 has is an inhibitor of glutamate transporters[45] and also has antibiotic activity[46]. Two backbone altered substrates, alpha-methyl Asp (D2) and N-methyl Asp (D3) can be charged[25], but efficient translation with these analogs is difficult.[43]

2.5. CysRS.

Only one analog of cysteine has been shown to be activated by ecCysRS, selenocysteine (C1)[47,48] (Fig. 3). A point mutant that activates C1 more efficiently has also been described[47]. C1 is a good translation substrate, and opens up opportunities for selective chemical transformations[47] and cyclization[49,50].

Figure 3. ncAA substrates for ecCysRS, ecGluRs, and ecGlnRS.

aGlnRS C229R/Q255I/S227A/F233Y.

2.6. GluRS.

To my knowledge the only paper looking at analogs of GluRS is by Hartman and Szostak[25]. Their MALDI screen showed that ecGluRS is quite tolerant towards substitutions at the gamma position; both fluorination (E1-E3) and methylation (E4-E5) is allowed at this position, although the methylated analogs are weaker substrates[43] (Fig. 3). Interestingly, two glutamate receptor agonist natural products, quisqualic acid (E6) and ibotenic acid (E7) also resemble Glu enough to be charged by ecGluRS. However; for any of these analogs, incorporation in living cells will be challenging due to the very high concentration of glutamic acid in the cytoplasm of cells[18], and the lack of a Glu auxotrophic strain for conducting selective pressure incorporation experiments[17].

2.7. GlnRS.

To my knowledge, the substrate scope of ecGlnRS has been sparsely studied; however, near-natural analogs containing hydrazide (Q1), ethylated amide (Q2), and urea (Q3) groups have been shown to be substrates[25] (Fig. 3). In addition, Perona created a mutant GlnRS that can activate glutamic acid (Q4)[51].

2.8. HisRS.

A decent number of alternate substrates for ecHisRS have been explored (Fig. 4). The 2- and 4-fluoro analogs are excellent substrates (H1-H2)[52], as are the 1,2,3 and 1,2,4 triazoles, H3 and H4[53–55]. My lab in collaboration with Ashton Cropp has exploited the lower pKa of the imidazole group of H2 to enable selective capture of peptides containing six H2 residues on nickel beads under low pH conditions[56]. Both N-methylated analogs (H5 and H6) are weak substrates[57,58]. The thiazole analog of His, H7[25], and 2-thio-His[58], H8, are also substrates. ecHisRS is also able to activate both N-Me His (H9) and d-His (H10), but both are poor substrates for the translation apparatus[25]. Work by Söll and Umehara to create a strain of E. coli where ecHisRS made orthogonal through replacement by C. crescentus HisRS/tRNAHis [58] bodes well for future engineering of this enzyme.

Figure 4. ncAA substrates for ecHisRS and ecIleRS.

aIleRS T243R, D342A.

2.9. IleRS.

The substrate scope of IleRS has been explored, and studies have shown some surprising substrate plasticity (Fig. 4). This plasticity can be further extended by blocking the second, editing active site that is responsible for improving fidelity through hydrolysis of non-cognate AA-tRNAs (e.g Val-tRNAIle)[34]. All the aliphatic analogs described so far as substrates for the wild-type IleRS have beta branching, while the editing-deficient mutant will also accept some straight chain analogs[34]. A number of groups have looked at fluorinated analogs, and a wide variety of mono and tri-fluoro substituted analogs of Ile, Leu, and Val are substrates (I1-I5)[16,34,59,60]. Tirrell has exploited I1 for the stabilization of β-zip peptides[60]. Koksch has extensively studied the ability of IleRS to charge and edit I3, which is activated by IleRS but is also edited off in a post-transfer mechanism[34]. IleRS also tolerates terminal olefin (I6)[61,62] and thioether (I7)[26] substituted analogs of Ile. Two different alkyl chlorides, I8 and I9 have also been described as substrates by Easton[63] and represent interesting electrophiles. Surprisingly, a MALDI screening assay also revealed that IleRS can activate the aryl amino acids phenylglycine (I10) and 2-thienyl glycine (I11), as well as cyclohexyl glycine (I12)[25]. Two novel substrates include the interesting natural products furanomycin (I13)[64] and acevicin (I14).[25], which is also a γ-glutamyl transpeptidase inhibitor.

2.10. LeuRS.

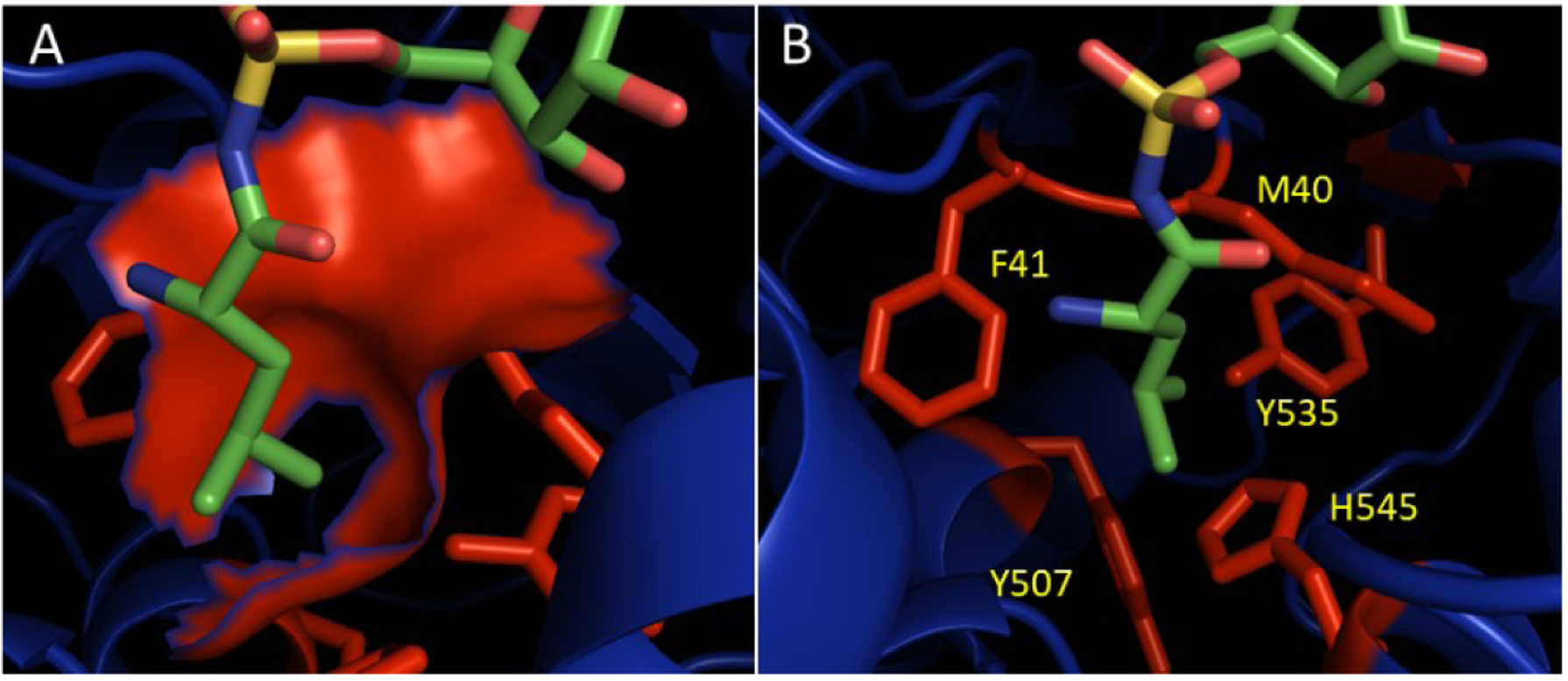

Wild-type and mutant E. coli LeuRS have been explored extensively and a huge array of AA substrates have been uncovered. The ecLeuRS/tRNALeu pair has been shown to be orthogonal in yeast,[65] which has motivated a significant number of mutagenesis studies. This enzyme is particularly amenable to alterations in substrate specificity because it has a large and malleable binding pocket (Fig. 5A). Amino acids in the binding site surrounding Leu side chain (Fig. 5B) have been extensively mutated leading to enzymes with remarkable activity towards ncAAs that are very different from Leu. EcLeuRS also has an editing site, and deactivation of the editing activity has led to an expansion in the ncAA substrate specificity[66].

Figure 5. Active site of E. coli LeuRS.

(A) ecLeuRS binding pocket surface is shown in red. The side chain of Leu sitting in the pocket is shown in green. (B) A sample of residues that form the Leu binding pocket that have been mutated. Images were made using Pymol from pdb 1H3N[67].

A large number of near-cognate amino acids have been explored (Fig. 6). Mono-, Tri- and Hexa-fluoro Leu (L1-L3) have been investigated both in in vitro translation and in auxotrophic bacteria[25,26,34,63,68,69]. Coiled, coil proteins containing L3 are significantly more stable to denaturation than those containing Leu[68]. The wild-type enzyme can also activate t-butyl Leu (L4)[25,69], cyclopentyl-alanine (L5)[25] and dehydro variants L6 and L7[63,70–72]. An editing deficient version (T252Y) has been exploited by Tirrell to introduce a number of additional alkenes (L8-L9), alkynes (L10-L11) and straight chain alkanes (L12-L13)[66]. Each of these can be incorporated in selective pressure incorporation experiments. An evolved ecLeuRS mutant described by Schultz that can activate amino acids with long-chain hydrocarbon side chains (L14-L16) has also been developed[24,73].

Figure 6. ncAA substrates for ecLeuRS.

aLeuRS D252A. bLeuRS M40V, L41M, Y499L, Y527L, H537G, cLeuRS M40I, Y499I, Y527A, H537G. dLeuRS M40L, L41E, Y499R, Y527A, H537G. eLeuRS M40G, L41Q, Y499L, Y527G, H537F. fLeuRS M40W, L41S, Y499I, Y527A, H537G. gLeuRS M40G, L41P, Y499G, Y527A, H537T. hLeuRS L38F, M40G, L41P, Y499V, Y500L, Y527A, H537G, L538S, F541C, A560V. iLeuRS M40A, L41N, T252Y, Y499I, Y527G, and H537T. jLeuRS M40G, L41K, Y499S, Y527A, H537G.

EcLeuRS has also been fruitfully studied for the incorporation of a wide variety of interesting functional groups, including a ketone (L17)[71], a diazirine photoaffinity label (L18)[43], and a tertiary amine analog where the methine carbon is replaced with a nitrogen (L19)[25]. Alkyl chlorides L21 and L22 have been shown to be substrates by Easton[61]. Mutant LeuRS’s can also activate methionine analogs L22 and L23 and even amino acids with long-chain thiols (L24-L25)[74].

The specificity of the LeuRS active site has been pushed even further through directed evolution with some spectacular results. A wide variety of aryl amino acids, even those with very large side chains have been uncovered. p-Methoxy phenylalanine (L26)[73], and photocaged analogs of serine (L27)[75], cysteine (L28-L30)[65,76,77] and selenocysteine (L31)[76,78,79] are substrates for various mutants. Schultz has used the AARS that activates L27 and its tRNA as an orthogonal system in yeast to control protein serine phosphorylation in a spatiotemporal manner[75]. Mutant ecLeuRS enzymes activating naphthalene (L32)[80], naphthalene ketone (L33)[80,81] and even the very large dansyl group (L34)[73,82,83] have been described; each of these amino acids can serve as a useful fluorescent reporter within proteins. A mutant activating the ferrocene amino acid L35 has also been reported[84].

Finally, wild-type LeuRS has been shown to activate various backbone-modified analogs, including the alpha-alpha disubstituted 1-aminocyclohexane and cyclopentane carboxylic acids (L36-L37)[25], and alpha-hydroxy substituted compound L38[72]. N-methyl Leu (L39) and β3-Leu (L40) have also been activated, although they are poor substrates in translation[25,43].

2.11. LysRS.

EcLysRS has been sparsely explored with regards to ncAAs (Fig. 8, below). The conservative substitutions giving rise to thialysine (K1)[25,26] and selenalysine (K2)[85] are tolerated. Seebeck and Szostak used analog K2 as a surrogate for dehydroalanine, leading to lantiboitic-like peptide libraries[86]. LysRS also tolerates introduction of a trans double bond between the gamma and delta carbons (K3)[25]. LysRS can activate the β3 analog of lysine (K4), N-methyl lysine (K5), and d-lysine (K6), although each of these are challenging to incorporate into peptides or proteins[25,43].

Figure 8. ncAA substrates for ecLysRS and ecMetRS.

aMetRS L13P, A256G, P257T, Y260Q, H301F. bMetRS L13G or MetRS L13P, Y260L, H301L. cMetRS L13S, Y250L, H301L. cMetRS L13G or MetRS L13P, Y260L, H301L.

2.12. MetRS.

The substrate scope ecMetRS has been investigated comprehensively, finding analogs consistent with its narrow but deep active site pocket (Fig 7A). Mutagenesis of residues around this pocket (Fig 7B) has led to expanded substrate scope.

Figure 7. Active site of E. coli MetRS.

(A) The ecMetRS binding pocket surface is shown in blue. The side chain of Met sitting in the pocket is shown in green and yellow (for sulfur). (B) Residues that form the Met binding pocket that have been mutated. Images were made using Pymol from pdb 1P7P[87].

Wild-type and mutant ecMetRS enzymes tolerate most non-branched amino acids with side chains containing 3–6 atoms (Fig. 8). This includes hydrocarbons (M1-M3)[25,39,69,88–92], terminal or trans-alkenes (M4-M6)[25,39,90], terminal or internal alkynes (M7-M10)[39,88,89,91,93–95], and hydrocarbons terminating in a trifluoromethyl group (M11-M12)[25,96,97]. Cyclopropylalanine (M13) is also a substrate[25].

Various heteroatom substituted analogs have also been described as substrates. Selenium, oxygen, and even tellurium is tolerated in place of the sulfur (M14-M16)[98,99], The sulfur can also be alkylated with fluroromethyl groups (M17-M18)[87] or longer chains including the ethyl (M19)[25,69,100] or allyl (M20)[101] groups. S-allyl cysteine (M21) is also a weak substrate for MetRS[101], and this leads to poor incorporation efficiency (it’s competence in translation in E. coli has been confirmed with an engineered PylRS[102]). S-allyl homocysteine (M21) is a better substrate[25,101], and is a powerful reagent for site-selective labeling via cross metathesis or click chemistry[101]. Azide M22 has been exploited extensively for labeling, and by Link and my group for the creation of cyclic peptides or proteins[25,26,28,69,88,92,103,104]. Tirrell and Link have investigated mutant MetRS enzymes that can activate the longer-chain azide M23[105–107] or shorter chain alkyne M7[93] to avoid competition with endogenous Met for cellular labeling[93]. Azide M24 is a weaker substrate[108]. Surprisingly ecMetRS can also tolerate a few amino acids with polar side chains; the methyl esters of aspartic (M25)[25] and glutamic (M26)[25,69] acids are substrates. EcMetRS has been shown to activate the β3-Met analog M27 although it is a poor substrate[25,109]. The hydroxy acid M28 is also a substrate[25] and can be incorporated into peptides, but because this analog does not contain an alpha-amino group, it is not processed efficiently by the translation initiation machinery[43].

2.13. PheRS.

Wild-type ecPheRS has been used to incorporate a wide variety of aromatic ncAAs. Early on, Hennecke described a A294G mutant which has an expanded binding pocket (Fig. 9A) near the binding site of para position of the phenyl ring[110] (Fig. 9B). A further mutant described by Tirrell (T251G, A294G), has an even more open binding pocket[111].

Figure 9. Active site of E. coli PheRS.

(A) The ecPheRS binding pocket surface is shown in red. The side chain of Phe sitting in the pocket is shown in green. (B) Two residues that form the Phe binding pocket have been mutated. Images were made using Pymol from pdb 3PCO[112].

A wide variety of 4-substituted Phe analogs have been described (Fig. 10). The wild-type enzyme can only activate 4-fluoro Phe (F1)[63,113–116], but the A294G mutant allows for the incorporation of many analogs. The halogen series can be activated (F2-F4) as well as the 4-cyano (F5), azido (F6), and alkyno (F7) derivatives[25,94,103,117,118]. The azido Phe, F6, can be used as a photoaffinity label[119], and alkyne F7 has been used along with click chemistry for protein labeling or stapling[94,103] or, by us for the creation of diverse bicyclic peptide libraries[28,120]. 4-Nitro Phe (F8) is also a weak substrate for the A294G mutant[25]. The T251G, A294G double-mutant is also able to use the ketone containing F9 which has been used as a reactive and selective handle for protein derivatization[111]. Wang and Matthews[114] have recently investigated 3-substituted analogs, showing the wild-type enzyme to be quite tolerant to substitution at the 3 position. Analogs include the fluoro (F10)[70,92,114,115], chloro (F11)[114], methyl (F12)[114], hydroxy groups (F13)[114] as well as 3,3-disubstituted analogs F14, F15, and F16[114]. 2-substituted analogs, F17[25,26,40,70,115] and F18[114] have also been shown to be substrates, although substitution at this position is less tolerated than the 3-position[114].

Figure 10. ncAA substrates for ecPheRS.

aPheRS A294G. bPheRS T251G, A294G.

The wild-type enzyme is also able to tolerate aliphatic substitutions on the β-carbon, either methyl or hydroxy substitutions (F19-F21)[25,121]. Various researchers have also explored changing the type of aromatic ring. Pyridines (F22-F24)[69,117], thiophenes (F25-F26)[25,69,121,122] and even an acyclic trisubstituted olefin (F27)[121] can be used in place of benzene. The A294G and T251G/A294G mutant is also able to activate the interesting benzofuran analog F28 as shown by Nielsen[123]. Finally, wtPheRS is also able to activate the β−2 analog of phenylalanine (F29) with reasonable efficiency, although it is a poor substrate in downstream translation[25].

2.14. ProRS.

The substrate specificity of ecProRS has been explored (Fig. 11); much of the work has been done by Conticello[124,125]. Most of the analogs consist of conservative substitutions around the ring. The enzyme tolerates fluorination at the 3 and 4 positions (P1-P4)[69,89,124–127]; these analogs have different ring pucker characteristics which makes them interesting structural probes[124,126]. Both 4-hydroxy proline diastereomers (P5-P6) are also substrates[69,89,92,124,128]. Alpha methyl Pro (P7) is also a substrate for ProRS, but downstream translation with this analog is challenging[25]. The 4,4-difluoro analog, P8, has also been studied[124]. Alterations within the ring itself have been explored. 3,4-dehydro Pro, P9[25,124], as well as both thiazolidine ring-analogs P10[25,69] and P11[124,129] are substrates. Ring size has also been varied. The plant toxin azetidine-2-carboxylic acid (P12)[130] is a well-known substrate[25,124]. Conticello created the C443G mutant which is able to activate the ring expanded piperidine analog P13[124]. Both P12 and P13 are interesting conformational probes[124].

Figure 11. ncAA substrates for ProRS, SerRS, and ThrRS.

aProRS C443G.

2.15. SerRS.

EcSerRS substrates have not been explored extensively. β-methyl amino alanine (BMAA), S1, is a toxic amino acid[131] that is known to be a substrate[132] (Fig. 11). Recently Söll uncovered a couple of putative ecSerRS substrates in a translation screen (S2 and S3)[38]. These new substrates suggest that the SerRS enzyme can tolerate amino acids with substitutions at the β-carbon, and this could serve as an interesting avenue for future inquiry.

2.16. ThrRS.

To my knowledge, the only alternate ThrRS substrate known is β-hydroxynorvaline (T1)[25,26,40,133] (Fig. 11).

2.17. TrpRS.

A wide variety of Tryptophan analogs are substrates for ecTrpRS, and most are also easily incorporated into translated peptides or proteins in place of Trp. These analogs are easily accessed enzymatically[134], or, if working in auxotrophic bacteria, through feeding the modified indole into the media[135]. ecTrpRS has a large and moldable binding pocket (Fig. 12), and directed evolution of ecTrpRS has been explored by Chatterjee[136] who has established it as an orthogonal synthetase in mammalian systems.

Figure 12. Active site of E. coli TrpRS.

(A) The binding pocket surface of TrpRS is shown in red. The side chain of Trp sits in the pocket as shown in green. (B) Residues that form the TrpRS binding pocket thathave been mutated are shown in red with corresponding numbering. Images were made using Pymol from pdb 5V0I.

Much of the work testing Trp analogs has been performed by Budisa. Substitution at the 4-position is tolerated for fluoro[89,137–141], hydroxy[142], methyl[139,143,144] and amino[143,144] groups (W1-W4) (Fig. 13). Wild-type EcTrpRS tolerates a wide variety of 5-subtitutions including fluoro[25,69,137–141], bromo[25,136], hydroxy[25,89,136,140,145], and methoxy substituents[25,136] (W5-W8). Mutagenesis has permitted further substitutions at the 5-position including the azide (W9), propargyloxy (W10) and amino groups (W11)[136]. The 6-position can also be substituted (W12-W14)[137,139–141,146]. 7-substitued analogs have not been extensively explored, but the 7-fluoro Trp is a substrate (W15)[69,139]. The tetrafluoro analog (W16) was also reported as a substrate, but incorporation into proteins has not been established[147]. Substitutions on the indole nitrogen have not been well tolerated[147], although Söll reported that the N-formyl and N-boc analogs could be incorporated using stop-codon suppression (W17-W18)[72]. Since incorporation was not validated by MS, it is possible that they were metabolized to Trp or were contaminated with a small amount of Trp, giving false positives. To my knowledge, substitutions at the 2-position have not been explored.

Figure 13. ncAA substrates for ecTrpRS.

aTrpRS S8A, V144S, V146A. bTrpRS S8A, V144G, V146C.

The indole ring itself can be extensively altered by substitutions. The 4,5, and 7 positions have been replaced with nitrogen (W19-W21)[25,26,140,141,145,146,148,149]. 6-aza incorporation (via addition of the corresponding indole) was tested in auxotrophic bacteria, but incorporation failed[148]. 2-aza tryptophan (W22) has conflicting reports about its suitability as a translation substrate[150–152]. Chou and coworkers have recently investigated the 2,6 and 2,7 di-aza substrates (W23 and W24), as fluorescent probes of hydration[153–156]. The benzene ring in the imidazole can be substituted with a 5 member-ring containing a sulfur or selenium atom (W25-W28)[139]. The indole nitrogen can also be substituted with a sulfur[25], but this thiophene analog (W29) is a mediocre substrate in translation[43]. Surprisingly, S-benzyl cysteine, W30, and 2-iodo Phe (W31) also are substrates[72].

Finally, a few backbone analogs of Trp have been shown to be substrates including N-Me Trp (W32)[25,43], the alpha-hydroxy acid analog of Trp (W33)[72], and d-Trp (W34)[157]. W33 is a good substrate for the translation apparatus[72].

2.18. TyrRS.

The plasticity of the ecTyrRS active site (Fig. 14) has been exploited extensively, and a wide variety of AAs, many of which do not significantly resemble tyrosine, can be incorporated. The orthogonality of ecTyrRS/tRNATyr in yeast and mammalian systems[158] has served to motivate the directed evolution of a wide variety of mutants.

Figure 14. Active site of E. coli TyrRS.

(A) The ecTyrRS binding pocket surface is shown in red, with the Tyr side chain shown in green. (B) A sampling of residues that form the Tyr binding pocket that have been mutated are shown in red. Images were made using Pymol from pdb 1X8X[159].

The first group of analogs consists of amino acids that retain the 4-hydroxy group but have additional substitutions around the ring (Fig. 15). A wide variety of 3-substituted amino acids (Y1-Y9) are substrates[25,40,69,70,92,114,127,160–163], although those with larger substituents (Y3, Y4, Y8) require a mutated version of the AARS (Y37V, Q195C)[162,163]. Several labs have explored 2-fluoro Tyr (Y10)[7,92,161], and recently, Wang and Matthews have shown the wild-type enzyme to be fairly permissive to tyrosine analogs substituted at the 2-position (Y10-Y14)[114]. Multiple halogenations are tolerated (Y15-Y16)[72,161], as well as changing the benzene for a pyridine ring (Y17)[164].

Figure 15. ncAA substrates for ecTyrRS.

aTyrRS Y37V, Q195C. bMultiple mutants reported[158] cTyrRS Y37G, D165G, D182G, F183M, L186A. dTyrRS L71V, D18G. eTyrRS Y37V, D165G, D182S, F183M, L186A. fMultiple mutants reported[169]. gTyrRS Y37G, D182G, F183Y, L186M. hTyRRS Y37G, L56E, L71H, T76G, S120Y, A121H, D182G, F183I, L186G.

A wide variety of mutants have been described that can incorporate analogs that lack the 4-hydroxy group. These include a number of 4-substituted analogs including methoxyl (Y18)[22,158,165,166], and nitro (Y19)[72] compounds. Various reactive handles have also been introduced including the 4-acetyl (Y20) [22,158,165,167], iodo (Y21) [22,165,166], and azido (Y22) [22,158,165,166,168] compounds. Chatterjee developed a ecTyRS mutant that can activate sulfated tyrosine (Y22) and has used it for the overexpression of sulfated proteins both in mammalian cells and E. coli[169]. Other O-alkylated compounds include alkyne Y24[22,165,166,168], and chloroethyl Y25[22]. Mutant synthetases can activate the boronate (Y26)[22] and the photoaffinity label trifluoromethyldiazirine (Y27)[170]. The wild-type enzyme can also activate the trifluoro and dichloro analogs Y28 and Y29[72]. A TyrRS mutant that can activate benzophenone-containing derivatives has also been developed[158,165–167] for use as an orthogonal AARS/tRNA pair in yeast. Mapp and coworkers have explored a variety of substituted benzophenones (Y30-Y37) for this mutant, noting significant differences in photoaffinity labeling efficiencies[171,172]. Brauchi recently exported mutations from a M. janaschii enzyme into EcTyrRS, enabling a mutant that can activate coumarin amino acid Y38[173]. Finally, D-Tyrosine (Y39) is a surprisingly good substrate[2,32]; however it is hydrolyzed off of the tRNA by a selective de-acylase to prevent toxicity[157].

2.19. ValRS.

EcValRS has been extensively studied for the incorporation of ncAAs (Fig. 16). In particular, the editing deficient mutant T222P, long known to enable synthesis of Thr-tRNAVal and Cys-tRNAVal [174], has proven to charge a very diverse range of substrates.

Figure 16. ncAA substrates for ecValRS.

aValRS T222P.

A wide variety of straight and branched chain aliphatics are substrates for wild-type or mutant ValRS (V1-V4)[25,43,175,176]. The hydrocarbon side chains can also be substituted with cyano groups (V5), azide (V6), hydroxyl groups (V7), a thioether (V8), and ethers (V9-V10)[25,175]. Early experiments by Berg and Dieckmann[176] showed that chlorobutyric acid derivatives V11 and V12 are decent substrates; and more recently Easton showed that these interesting AAs could be incorporated into proteins[61].

A wide variety of mono- and tri-fluoro substitutions are also good substrates (V13-V16)[25,34,40,43,60,177]. Interestingly, V13, is a substrate, but not the C-3 epimer[177]. My lab has shown that ValRS and its editing-deficient mutants are able to charge a wide variety of β-amino acids, including β3 analogs of both alanine (V17) and valine (V18), as well as cyclic beta amino acids containing cyclohexane and cyclopentane rings (V19-V21)[25,175]. These analogs are known to exert unique conformational constraints into peptides, although their incorporation in translation requires significant engineering of the translation apparatus[178]. Szostak reported that cyclic alpha-alpha disubstituted amino acids V22 and V23 were good substrates for the wild-type enzyme[25], and used V23 within a diverse peptide library[27]. More recently my lab showed that the editing-deficient mutant can activate alpha-methyl analogs of alanine (V24)[175], serine (V25)[175], and cysteine (V26)[179]. The latter when incorporated into a cyclic peptide can serve as a suitable replacement for the standard hydrocarbon staple for promoting alpha-helical peptide conformations[179]. Finally, N-Methyl valine (V27) can be charged although it is a poor substrate for downstream translation[25,43].

3. Trends and applications of ncAA substrates

The list of ncAA substrates for ecAARS enzymes can be taken in several productive directions. For each, I highlight a particularly exciting or innovative application.

3.1. Fluorination.

A significant fraction of the ncAAs listed in these charts are fluorinated amino acids. The small size of the fluorine atom makes it an excellent substitute for a hydrogen. Budisa’s excellent review on global replacement with fluorinated ncAAs in proteins highlights the effects of these molecules on protein structure, catalysis, and their usefulness as NMR and vibrational spectroscopic probes[180]. Pomerantz has pioneered drug screening of protein binding by NMR using proteins globally substituted with fluorinated Trp and Tyr residues[181]. In a notable recent paper, Nash and coworkers investigated the impacts of the presence of trifluoro leucine on the stability of protein interfaces using single molecule force spectroscopy[182].

3.2. Bio-orthogonal chemistry.

Many of the amino acids described in the preceding lists have novel functional groups that can be used in bio-orthogonal reactions. Notable functional groups include hydrazides (Q1), ketones (L31, F9/Y19, Y29-Y35), azides (M20-M21, F6/Y22, W9, Y8), terminal alkynes (L11/M8, M7, F7, W10, Y24), alkyl chlorides (I9, I10, L20, L21, Y25), aryl iodides (F4/Y21, W31, Y4), an aryl boronate (Y26), and an S-allyl group (M18). Azides and alkynes have, in particular, been exploited using copper-mediated azide-alkyne cyclization or copper free click experiments for selective labeling[94,103,183]. The majority of these experiments have focused on analogs L11/M8 and M21 as methionine surrogates. These have been extensively exploited to monitor the production of new proteins inside cells and organisms through adding a pulse of the ncAA. This technology, developed by Tirrell and Schuman is known as BONCAT (Bio-orthogonal non-canonical amino acid tagging)[184]. The more recent development of Trp and Tyr analogs containing azides and alkynes (W9, W10, Y8, Y22, Y24) opens up new opportunities for selective labeling of aryl residues. The other functional groups in this list have not been extensively exploited and offer new avenues for protein labeling and peptide library cyclization.

3.3. Fluorescence.

Although native tryptophan is a weak fluorophore, fluorescent amino acids have been widely pursued for their enhanced fluorescent properties, including some ecAARS substrates[185]. Substituted tryptophans have altered wavelengths of emission and excitation, and in some cases, improved quantum yields[142,144,148,186,187]. Due to the lower molar absorptivity of these analogs, they are not as bright in fluorescence as some of the analogs activated by engineered AARS enzymes. Notable fluorescent compounds include Anap containing amino acid L33[188,189] and dansyl-derivatized L34[73,82,190]. Coumarin-containing Y38 also has excellent fluorescent properties[173,191]. These amino acids offer a potentially efficient route for the site-selective labeling of fluorescent proteins. The most impressive applications of these amino acids involve Anap (L33). Kalstrup and Blunck, incorporated L33 into several positions of a voltage-gated potassium channel and were able to observe changes in fluorescence under various voltages in patch clamp assays[190]. Sakata and coworkers used a similar strategy to investigate the activity of a voltage sensitive phosphatase[192]. The ability to site-specifically label these channels allowed for a detailed understanding of which parts of these membrane proteins undergo conformational changes as voltage changes. FRET with a membrane-embedded dye also allowed for analysis of how parts of the protein moved in relationship to the membrane[192].

3.4. Photoreactive groups.

Several amino acids bearing photoaffinity-labels have been developed, including those containing diazirane L18, trifluoromethyl diazirane Y27, aryl azide F6/Y22, benzofuran F28 and benzophenones Y30-Y37. Particularly interesting is amino acid Y37, developed by Joiner and coworkers. The benzophenone allows for crosslinking, while the alkyne group enables subsequent capture on streptavidin resin after click chemistry with biotin azide[172]. Hino and coworkers also established Y27 to map the interactions of the SH2 domain of GRB2 using proteomics followed by confirmation by Western blotting[170]. Photocaged serine, cysteine, and selenocysteine-containing amino acids, L27-L31 have also been developed as LeuRS substrates. In an impressive example, Kang and coworkers introduced a mutant ecLeuRS and suppressor tRNALeu into the mouse neocortex. In the presence of injected L29, they were able to control the activity of the Kir2.1 potassium channel with light in brain slices[77].

3.5. Posttranslational modifications.

Four of the ncAAs on this list correspond to known post-translational protein modifications. Monomethyl arginine (R2) and other arginine methylation patterns are involved in a variety of cellular pathways including splicing, cell metabolism and the DNA damage response, and the arginine methyltransferases have become hot drug targets in oncology[193]. The use of R2 as a substrate for ecArgRS has, to my knowledge, not been exploited in these studies. Hydroxylation of Pro-402 or Pro-564 of HIF-1α giving trans-4-hydroxyproline (P6) is an essential component of the cellular response to oxygen levels[194]. 3-nitrotyrosine (Y9) is a post-translational chemical modification that is indicative of oxidative stress[195,196]; however, the incorporation of nitro-Tyr using ecTyrRS is weak[43,114] and this has limited any useful studies. In an impressive feat of engineering, Italia et. al. developed a TyrRS that can directly incorporate sulfated tyrosine (Y23) into proteins in mammalian cells and were able to study the effect of tyrosine sulfation at specific sites in a thrombin inhibitor protein, heparin cofactor II[169].

3.6. Parameterization of local electric fields and vibrational energy transfer.

A emerging application of some of these ncAAs involves probing the electrostatics of enzyme catalysis and binding by the vibrational stark effect—that is the change in IR stretching frequencies of a given functional group based on the local electric field[180]. Much of the work in this field has focused on ncAAs and engineered AARS from other organisms[180,197,198]; however, several of the ncAAs listed above contain functional groups with sufficient IR-stretching signals and sensitivity to the electronic environment to serve as vibrational probes. Alkyl and aryl fluorides, cyano groups (F5 and V5), azides (M20-M21, F6/Y22, W9, Y8), and nitro groups (F8, Y9) are all suitable candidates for these investigations[180,199]. Alternatively, one can introduce the vibrational probe into a bound ligand and use other ncAAs to alter the electronic nature of the protein binding site[180,197,198].

4. Summary and Outlook.

In the preceding paragraphs, I have listed the known substrates for E. coli wild-type and mutant enzymes. Some were uncovered out of curiosity for the enzyme substrate specificity or from broad screens. Others were investigated due to their natural origin. Still others were developed with an eye towards protein engineering. By combining research from each of these sources into one location, a full picture of the specificity and engineerability of these enzymes can be highlighted. The diversity of amino acids activated by these proteins is quite amazing, and due to E. coli’s central role in molecular biology, this database of ncAA substrates serves a unique and valuable toolkit of molecular function. As such this review is a valuable resource to inspire new directions in protein engineering, synthetic biology and peptide drug discovery.

5. Acknowledgments.

MCTH gratefully acknowledges support by the NIH (R03CA259876 and R03CA216116) and NSF (190482) and thanks lab members Bipasana Shakya, Cal McFeely, Kara Dods, Gigi Kerestesy, Anthony Le, Chelsea Simek, and Estheban Franco for helpful suggestions on the manuscript.

Biography

Matthew C. T. Hartman received his Ph.D. degree from the University of Michigan in 2002, studying under Professor James Coward. He was then a HHMI postdoctoral fellow with Professor Jack Szostak at Harvard University (2002–2006). Since 2007 he has been at Virginia Commonwealth University where he currently is a Professor in the Department of Chemistry and the Massey Cancer Center. His research interests focus on the discovery of natural-product like peptide inhibitors of protein-protein interactions and the delivery and activation of chemotherapeutic agents with light.

6. References

- [1].Hortin G, Boime I, Methods Enzymol 1983, 96, 777–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Calendar R, Berg P, J. Mol. Biol 1967, 26, 39–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Fowden L, Richmond MH, Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1963, 71, 459–461. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Brabham R, Fascione MA, ChemBioChem 2017, 18, 1973–1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Dumas A, Lercher L, Spicer CD, Davis BG, Chem. Sci 2015, 6, 50–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Budisa N, Angew. Chemie - Int. Ed 2004, 43, 6426–6463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Merkel L, Budisa N, Org. Biomol. Chem 2012, 10, 7241–7261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Hendrickson TL, De Crécy-Lagard V, Schimmel P, Annu. Rev. Biochem 2004, 73, 147–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Voloshchuk N, Montclare JK, Mol. Biosyst 2009, 6, 65–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Melnikov SV, Söll D, Int. J. Mol. Sci 2019, 20, DOI 10.3390/ijms20081929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Kaiser F, Krautwurst S, Salentin S, Haupt VJ, Leberecht C, Bittrich S, Labudde D, Schroeder M, Sci. Rep 2020, 10, 1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Vargas-Rodriguez O, Sevostyanova A, Söll D, Crnković A, Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol 2018, 46, 115–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Kim Y, Opron K, Burton ZF, Life 2019, 9, 37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Pang YLJ, Poruri K, Martinis SA, Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA 2014, 5, 461–480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Gomez MAR, Ibba M, RNA 2020, 26, 910–936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Fang KY, Lieblich SA, Tirrell DA, in Methods Mol. Biol, Humana Press Inc., 2018, pp. 173–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Lin MT, Fukazawa R, Miyajima-Nakano Y, Matsushita S, Choi SK, Iwasaki T, Gennis RB, in Isot. Labeling Biomol. - Labeling Methods (Ed.: Z.B.T.-M. in Kelman), Academic Press, 2015, pp. 45–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Bennett BD, Kimball EH, Gao M, Osterhout R, Van Dien SJ, Rabinowitz JD, Nat. Chem. Biol 2009, 5, 593–599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Bacher JM, Ellington AD, J. Bacteriol 2001, 183, 5414–5425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Agostini F, Sinn L, Petras D, Schipp CJ, Kubyshkin V, Berger AA, Dorrestein PC, Rappsilber J, Budisa N, Koksch B, ACS Cent. Sci 2020, 7, 81–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Hoesl MG, Oehm S, Durkin P, Darmon E, Peil L, Aerni HR, Rappsilber J, Rinehart J, Leach D, Söll D, Budisa N, Angew. Chemie - Int. Ed 2015, 54, 10030–10034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Italia JS, Latour C, Wrobel CJJ, Chatterjee A, Cell Chem. Biol 2018, 25, 1304–1312.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Ding W, Zhao H, Chen Y, Zhang B, Yang Y, Zang J, Wu J, Lin S, Nat. Commun 2020, 11, 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Brustad E, Bushey ML, Brock A, Chittuluru J, Schultz PG, Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett 2008, 18, 6004–6006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Hartman MCTT, Josephson K, Szostak JW, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 2006, 103, 4356–4361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Josephson K, Hartman MCTT, Szostak JW, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2005, 127, 11727–11735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Guillen Schlippe YV, Hartman MCTT, Josephson K, Szostak JW, V Schlippe Y, Hartman MCTT, Josephson K, Szostak JW, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2012, 134, 10469–10477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Hacker DE, Hoinka J, Iqbal ES, Przytycka TM, Hartman MCT, ACS Chem. Biol 2017, 12, 795–804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Huang Y, Wiedmann MM, Suga H, Chem. Rev 2019, 119, 10360–10391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Francklyn CS, First EA, Perona JJ, Hou YM, Methods 2008, 44, 100–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Fersht AR, Ashford JS, Bruton CJ, Jakes R, Koch GLE, Hartley BS, Biochemistry 1975, 14, 1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Calendar R, Berg P, Biochemistry 1966, 5, 1690–1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Wolfson AD, Uhlenbeck OC, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2002, 99, 5965–5970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Völler JS, Dulic M, Gerling-Driessen UIM, Biava H, Baumann T, Budisa N, Gruic-Sovulj I, Koksch B, ACS Cent. Sci 2017, 3, 73–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Ho JM, Reynolds NM, Rivera K, Connolly M, Guo LT, Ling J, Pappin DJ, Church GM, Söll D, ACS Synth. Biol 2016, 5, 163–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Bilus M, Semanjski M, Mocibob M, Zivkovic I, Cvetesic N, Tawfik DS, Toth-Petroczy A, Macek B, Gruic-Sovulj I, J. Mol. Biol 2019, 431, 1284–1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Nehring S, Budisa N, Wiltschi B, PLoS One 2012, 7, e31992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Fan C, Ho JML, Chirathivat N, Söll D, Wang Y-S, ChemBioChem 2014, 15, 1805–1809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Kiick KL, Weberskirch R, Tirrell DA, FEBS Lett 2001, 502, 25–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Oh SJ, Lee KH, Kim HC, Catherine C, Yun H, Kim DM, Biotechnol. Bioprocess Eng 2014, 19, 426–432. [Google Scholar]

- [41].Schachtele CF, Rogers P, J. Mol. Biol 1965, 14, 474–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Worst EG, Exner MP, De Simone A, Schenkelberger M, Noireaux V, Budisa N, Ott A, Bioorganic Med. Chem. Lett 2015, 25, 3658–3660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Hartman MCT, Josephson K, Lin CW, Szostak JW, PLoS One 2007, 2, e972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Babu BR, Griffith OW, J. Biol. Chem 1998, 273, 8882–8889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Balcar VJ, Johnston GA, Twitchin B, J. Neurochem 1977, 28, 1145–1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Ishiyama T, Furuta T, Takai M, Okimoto Y, J. Antibiot. (Tokyo) 1975, 28, 821–823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Hoffman KS, Vargas-Rodriguez O, Bak DW, Mukai T, Woodward LK, Weerapana E, Söll D, Reynolds NM, Noah X, Reynolds M, Reynolds NM, J. Biol. Chem 2019, 294, 12855–12865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Kaiser I, Arch Biochem Biophys 1975, 171, 483–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Dantas de Araujo A, Perry SR, Fairlie DP, Org. Lett 2018, 20, 1453–1456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Yin Y, Fei Q, Liu W, Li Z, Suga H, Wu C, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl 2019, 58, 4880–4885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Bullock TL, Rodríguez-Hernández A, Corigliano EM, Perona JJ, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2008, 105, 7428–7433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Eichler JF, Cramer JC, Kirk KL, Bann JG, ChemBioChem 2005, 6, 2170–2173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Ikeda Y, Kawahara SI, Taki M, Kuno A, Hasegawa T, Taira K, Protein Eng 2003, 16, 699–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Schlesinger MJ, J. Biol. Chem 1967, 242, 3369–3372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Soumillion P, Fastrez J, Protein Eng 1998, 11, 213–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Ring CM, Iqbal ES, Hacker DE, Hartman MCT, Cropp TA, Org. Biomol. Chem 2017, 15, 4536–4539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Schlesinger S, Schlesinger MJ, J. Biol. Chem 1969, 244, 3803–3809. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Englert M, Vargas-Rodriguez O, Reynolds NM, Wang YS, Söll D, Umehara T, Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Gen. Subj 2017, 1861, 3009–3015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Wang P, Tang Y, Tirrell DA, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2003, 125, 6900–6906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Son S, Tanrikulu IC, Tirrell DA, ChemBioChem 2006, 7, 1251–1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Stigers DJ, Watts ZI, Hennessy JE, Kim HK, Martini R, Taylor MC, Ozawa K, Keillor JW, Dixon NE, Easton CJ, Chem. Commun 2011, 47, 1839–1841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Mock ML, Michon T, Van Hest JCM, Tirrell DA, ChemBioChem 2006, 7, 83–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Arthur IN, Hennessy JE, Padmakshan D, Stigers DJ, Lesturgez S, Fraser SA, Liutkus M, Otting G, Oakeshott JG, Easton CJ, Chem. - A Eur. J 2013, 19, 6824–6830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Kohno T, Kohda D, Haruki M, Yokoyama S, Miyazawa T, J. Biol. Chem 1990, 265, 6931–6935. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Wu N, Deiters A, Cropp TA, King D, Schultz PG, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2004, 126, 14306–14307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Tang Y, Tirrell DA, Biochemistry 2002, 41, 10635–10645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Cusack S, Yaremchuk A, Tukalo M, EMBO J 2000, 19, 2351–2361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Tang Y, Tirrell DA, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2001, 123, 11089–11090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Canu N, Belin P, Thai R, Correia I, Lequin O, Seguin JJJJ, Moutiez M, Gondry M, Angew. Chemie - Int. Ed 2018, 130, 3172–3176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Liutkus M, Fraser SA, Caron K, Stigers DJ, Easton CJ, ChemBioChem 2016, 17, 908–912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Tang Y, Wang P, Van Deventer JA, Link AJ, Tirrell DA, ChemBioChem 2009, 10, 2188–2190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Fan C, Ho JML, Chirathivat N, Söll D, Wang YS, ChemBioChem 2014, 15, 1805–1809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Wang J, Xie J, Schultz PG, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2006, 128, 8738–8739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Brustad E, Bushey ML, Brock A, Chittuluru J, Schultz PG, Bioorganic Med. Chem. Lett 2008, 18, 6004–6006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Lemke EA, Summerer D, Geierstanger BH, Brittain SM, Schultz PG, Nat. Chem. Biol 2007, 3, 769–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Rakauskaitė R, Urbanavičiūtė G, Simanavičius M, Lasickienė R, Vaitiekaitė A, Petraitytė G, Masevičius V, Žvirblienė A, Klimašauskas S, iScience 2020, 23, DOI 10.1016/j.isci.2020.101833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Kang JY, Kawaguchi D, Coin I, Xiang Z, O’Leary DDM, Slesinger PA, Wang L, Neuron 2013, 80, 358–370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Peeler JC, Falco JA, Kelemen RE, Abo M, Chartier BV, Edinger LC, Chen J, Chatterjee A, Weerapana E, ACS Chem. Biol 2020, 15, 1535–1540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Rakauskaite R, Urbanavičiute G, Rukšenaite A, Liutkevičiute Z, Juškenas R, Masevičius V, Klimašauskas S, Chem. Commun 2015, 51, 8245–8248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Lee HS, Guo J, Lemke EA, Dimla RD, Schultz PG, Hyun SL, Guo J, Lemke EA, Dimla RD, Schultz PG, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2009, 131, 12921–12923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Chatterjee A, Guo J, Lee HS, Schultz PG, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2013, 135, 12540–12543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Wang W, Takimoto JK, Louie GV, Baiga TJ, Noel JP, Lee KF, Slesinger PA, Wang L, Nat. Neurosci 2007, 10, 1063–1072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Wang Q, Wang L, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2008, 130, 6066–6067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Tippmann EM, Schultz PG, Tetrahedron 2007, 63, 6182–6184. [Google Scholar]

- [85].Seebeck FP, Szostak JW, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2006, 128, 7150–7151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Hofmann FT, Szostak JW, Seebeck FP, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2012, 134, 8038–8041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Crepin T, Schmitt E, Mechulam Y, Sampson PB, Vaughan MD, Honek JF, Blanquet S, J. Mol. Biol 2003, 332, 59–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Kiick KL, Saxon E, Tirrell DA, Bertozzi CR, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2002, 99, 19–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Oldach F, Altoma R, Kuthning A, Caetano T, Mendo S, Budisa N, Süssmuth RD, Angew. Chemie - Int. Ed 2012, 51, 415–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Kiick KL, Van Hest JCM, Tirrell DA, Angew. Chemie - Int. Ed 2000, 39, 2148–2152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Van Hest JCMM, Kiick KL, Tirrell DA, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2000, 122, 1282–1288. [Google Scholar]

- [92].Hoesl MG, Acevedo-Rocha CG, Nehring S, Royter M, Wolschner C, Wiltschi B, Budisa N, Antranikian G, ChemCatChem 2011, 3, 213–221. [Google Scholar]

- [93].Truong F, Hyeon Yoo T, Lampo TJ, Tirrell DA, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2012, 134, 8551–8556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Beatty KE, Xie F, Wang Q, Tirrell DA, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2005, 127, 14150–14151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Grammel M, Zhang MM, Hang HC, Angew. Chemie - Int. Ed 2010, 122, 6106–6110. [Google Scholar]

- [96].Yoo TH, Tirrell DA, Angew. Chemie - Int. Ed 2007, 119, 5436–5439. [Google Scholar]

- [97].Cowie DB, Cohen GN, BBA - Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1957, 26, 252–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Budisa N, Steipe B, Demange P, Eckerskorn C, Kellermann J, Huber R, Eur. J. Biochem 1995, 230, 788–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99].Wolschner C, Giese A, Kretzschmar HA, Huber R, Moroder L, Budisa N, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2009, 106, 7756–7761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [100].Spížek J, Janeček J, Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 1969, 34, 17–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [101].Bhushan B, Lin YA, Bak M, Phanumartwiwath A, Yang N, Bilyard MK, Tanaka T, Hudson KL, Lercher L, Stegmann M, Mohammed S, Davis BG, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2018, 140, 14599–14603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [102].Exner MP, Kuenzl T, To TMT, Ouyang Z, Schwagerus S, Hoesl MG, Hackenberger CPR, Lensen MC, Panke S, Budisa N, ChemBioChem 2017, 18, 85–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [103].Abdeljabbar DM, Piscotta FJ, Zhang S, Link AJ, Chem. Commun 2014, 50, 14900–14903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [104].Link AJ, Tirrell DA, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2003, 125, 11164–11165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [105].Tanrikulu IC, Schmitt E, Mechulam Y, Goddard WA, Tirrell DA, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2009, 106, 15285–15290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [106].Schmitt E, Tanrikulu IC, Yoo TH, Panvert M, Tirrell DA, Mechulam Y, J. Mol. Biol 2009, 394, 843–851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [107].Link AJ, Vink MKS, Agard NJ, Prescher JA, Bertozzi CR, Tirrell DA, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2006, 103, 10180–10185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [108].Link AJ, Vink MKS, Tirrell DA, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2004, 126, 10598–10602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [109].Nigro G, Bourcier S, Lazennec-Schurdevin C, Schmitt E, Marlière P, Mechulam Y, J. Struct. Biol 2020, 209, 107435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [110].Kast P, Hennecke H, J. Mol. Biol 1991, 222, 99–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [111].Datta D, Wang P, Carrico IS, Mayo SL, Tirrell DA, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2002, 124, 5652–5653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [112].Mermershtain I, Finarov I, Klipcan L, Kessler N, Rozenberg H, Safro MG, Protein Sci 2011, 20, 160–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [113].White ER, Sun L, Ma Z, Beckta JM, Danzig BA, Hacker DE, Huie M, Williams DC, Edwards RA, Valerie K, Glover JNMM, Hartman MCTT, ACS Chem. Biol 2015, 10, 1198–1208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [114].Wang Z, Matthews H, RSC Adv 2020, 10, 11013–11023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [115].Minks C, Huber R, Moroder L, Budisa N, Anal. Biochem 2000, 284, 29–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [116].Hughes SJ, Glover TW, Zhu XX, Kuick R, Thoraval D, Orringer MB, Beer DG, Hanash S, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 1998, 95, 12410–12415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [117].Kirshenbaum K, Carrico IS, Tirrell DA, ChemBioChem 2002, 3, 235–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [118].Sharma N, Furter R, Kast P, Tirrell DA, FEBS Lett 2000, 467, 37–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [119].Chin JW, Martin AB, King DS, Wang L, Schultz PG, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2002, 99, 11020–11024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [120].Hacker DE, Abrigo NA, Hoinka J, Richardson SL, Przytycka TM, Hartman MCT, ACS Comb. Sci 2020, 22, 306–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [121].Gabius HJ, von der Haar F, Cramer F, Biochemistry 1983, 22, 2331–2339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [122].Kothakota S, Mason TL, Tirrell DA, Fournier MJ, J. Am. Chem. Soc 1995, 117, 536–537. [Google Scholar]

- [123].Bentin T, Hamzavi R, Salomonsson J, Roy H, Ibba M, Nielsen PE, J. Biol. Chem 2004, 279, 19839–19845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [124].Kim W, George A, Evans M, Conticello VP, ChemBioChem 2004, 5, 928–936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [125].Kim W, Hardcastle KI, Conticello VP, Angew. Chemie - Int. Ed 2006, 45, 8141–8145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [126].Newberry RW, Raines RT, Top. Heterocycl. Chem 2017, 48, 1–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [127].Deepankumar K, Nadarajan SP, Mathew S, Lee S-GG, Yoo TH, Hong EY, Kim B-GG, Yun H, ChemCatChem 2015, 7, 417–421. [Google Scholar]

- [128].Buechter DD, Paolella DN, Leslie BS, Brown MS, Mehos KA, Gruskin EA, J. Biol. Chem 2003, 278, 645–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [129].Budisa N, Minks C, Medrano FJ, Lutz J, Huber R, Moroder L, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 1998, 95, 455–459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [130].Fowden L, Biochem. J 1956, 64, 323–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [131].Dunlop RA, Cox PA, Banack SA, Rodgers KJ, PLoS One 2013, 8, e75376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [132].Liu Z, Characterization of the in Vitro and in Vivo Specificity of Trans-Editing Proteins and Interacting Aminoacyl-TRNA Synthetases, Ohio State University, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- [133].Minajigi A, Deng B, Francklyn CS, Biochemistry 2011, 50, 1101–1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [134].Lee M, Phillips R, Bioorg Med Chem Lett 1992, 2, 1563–1564. [Google Scholar]

- [135].Crowley PB, Kyne C, Monteith WB, Chem. Commun 2012, 48, 10681–10683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [136].Italia JS, Addy PS, Wrobel CJJ, Crawford LA, Lajoie MJ, Zheng Y, Chatterjee A, Nat. Chem. Biol 2017, 13, 446–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [137].Minks C, Huber R, Moroder L, Budisa N, Biochemistry 1999, 38, 10649–10659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [138].Pratt EA, Chien H, Biochemistry 1975, 14, 3035–3040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [139].Budisa N, Pal PP, Alefelder S, Birle P, Krywcun T, Rubini M, Wenger W, Bae JH, Steiner T, Biol. Chem 2004, 385, 191–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [140].Wong C-Y, Eftink MR, Biochemistry 1998, 37, 8947–8953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [141].Wong CY, Eftink MR, Biochemistry 1998, 37, 8938–8946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [142].Budisa N, Rubini M, Bae JH, Weyher E, Wenger W, Golbik R, Huber R, Moroder L, Angew. Chemie - Int. Ed 2002, 41, 4066–4069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [143].Rubini M, Lepthien S, Golbik R, Budisa N, Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Proteins Proteomics 2006, 1764, 1147–1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [144].Bae JH, Rubini M, Jung G, Wiegand G, Seifert MHJ, Azim MK, Kim JS, Zumbusch A, Holak TA, Moroder L, Huber R, Budisa N, J. Mol. Biol 2003, 328, 1071–1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [145].Wong CY, Eftink MR, Protein Sci 1997, 6, 689–697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [146].Pardee AB, Prestidge LS, BBA - Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1958, 27, 330–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [147].Azim MK, Budisa N, Biol. Chem 2008, 389, 1173–1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [148].Lepthien S, Hoesl MG, Merkel L, Budisa N, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2008, 105, 16095–16100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [149].Soumillion P, Jespers L, Vervoort J, Fastrez J, Protein Eng. Des. Sel 1995, 8, 451–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [150].Attias J, Schlesinger MJ, Schlesinger S, Schlesinger MJ, J. Biol. Chem 1969, 244, 3803–3809. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [151].Brawerman G, Ycas M, Arch. Biochem. Biophys 1957, 68, 112–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [152].Ross JBA, Szabo AG, Hogue CWV, Methods Enzymol 1997, 278, 151–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [153].Shen JY, Chao WC, Liu C, Pan HA, Yang HC, Chen CL, Lan YK, Lin LJ, Wang JS, Lu JF, Chun-Wei Chou S, Tang KC, Chou PT, Nat. Commun 2013, 4, 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [154].Chao WC, Shen JY, Yang CH, Lan YK, Yuan JH, Lin LJ, Yang HC, Lu JF, Wang JS, Wee K, Chen YH, Chou PT, Biophys. J 2016, 110, 1732–1743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [155].Chao WC, Lu JF, Wang JS, Chiang TH, Lin LJ, Lee YL, Chou PT, Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Gen. Subj 2020, 1864, 129483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [156].Chao WC, Lin LJ, Lu JF, Wang JS, Lin TC, Chen YHTH, Chen YHTH, Yang HC, Chou PT, Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Gen. Subj 2018, 1862, 451–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [157].Soutourina J, Plateau P, Blanquet S, J. Biol. Chem 2000, 275, 32535–32542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [158].Chin JW, Cropp TA, Anderson JC, Mukherji M, Zhang Z, Schultz PG, Science (80-.) 2003, 301, 964–967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [159].Kobayashi T, Takimura T, Sekine R, Vincent K, Kamata K, Sakamoto K, Nishimura S, Yokoyama S, J. Mol. Biol 2005, 346, 105–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [160].Goulding A, Shrestha S, Dria K, Hunt E, Deo SK, Protein Eng. Des. Sel 2008, 21, 101–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [161].Brooks B, Phillips RS, Benisek WF, Biochemistry 1998, 37, 9738–9742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [162].Kiga D, Sakamoto K, Kodama K, Kigawa T, Matsuda T, Yabuki T, Shirouzu M, Harada Y, Nakayama H, Takio K, Hasegawa Y, Endo Y, Hirao I, Yokoyama S, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2002, 99, 9715–9720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [163].Iraha F, Oki K, Kobayashi T, Ohno S, Yokogawa T, Nishikawa K, Yokoyama S, Sakamoto K, Nucleic Acids Res 2010, 38, 3682–3691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [164].Hamano-Takaku F, Iwama T, Saito-Yano S, Takaku K, Monden Y, Kitabatake M, Söll D, Nishimura S, J. Biol. Chem 2000, 275, 40324–40328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [165].Liu W, Brock A, Chen SS, Chen SS, Schultz PG, Nat. Methods 2007, 4, 239–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [166].Young TS, Ahmad I, Brock A, Schultz PG, Biochemistry 2009, 48, 2643–2653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [167].Ye S, Köhrer C, Huber T, Kazmi M, Sachdev P, Yan ECY, Bhagat A, RajBhandary UL, Sakmar TP, J. Biol. Chem 2008, 283, 1525–1533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [168].Deiters A, Cropp TA, Mukherji M, Chin JW, Anderson JC, Schultz PG, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2003, 125, 11782–11783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [169].Italia JS, Peeler JC, Hillenbrand CM, Latour C, Weerapana E, Chatterjee A, Nat. Chem. Biol 2020, 16, 379–382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [170].Hino N, Oyama M, Sato A, Mukai T, Iraha F, Hayashi A, Kozuka-Hata H, Yamamoto T, Yokoyama S, Sakamoto K, J. Mol. Biol 2011, 406, 343–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [171].Joiner CM, Breen ME, Mapp AK, Protein Sci 2019, 28, 1163–1170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [172].Joiner CM, Breen ME, Clayton J, Mapp AK, ChemBioChem 2017, 18, 181–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [173].Steinberg X, Galpin J, Nasir G, Sepúlveda RV, Ladron de Guevara E, Gonzalez-Nilo F, Islas LD, Ahern CA, Brauchi SE, Heliyon 2020, 6, e05140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [174].Doring V, Mootz HD, Nangle LA, Hendrickson TL, de Crecy-Lagard V, Schimmel P, Marliere P, Science 2001, 292, 501–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [175].Iqbal ES, Dods KK, Hartman MCT, Org. Biomol. Chem 2018, 16, 1073–1078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [176].Bergmann FH, Berg P, Dieckmann M, J. Biol. Chem 1961, 236, 1735–1740. [Google Scholar]

- [177].Wang P, Fichera A, Kumar K, Tirrell DA, Angew. Chemie - Int. Ed 2004, 43, 3664–3666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [178].Katoh T, Sengoku T, Hirata K, Ogata K, Suga H, Nat. Chem 2020, 12, 1081–1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [179].Iqbal ES, Richardson SL, Abrigo N, Dods KK, Osorio-Franco HE, Gerrish HS, Kotapati HK, Morgan IM, Masterson DS, Hartman MCT, Chem. Commun 2019, 55, 8959–8962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [180].Völler JS, Biava H, Hildebrandt P, Budisa N, Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Gen. Subj 2017, 1861, 3053–3059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [181].Divakaran A, Kirberger SE, Pomerantz WCK, Acc. Chem. Res 2019, 52, 3407–3418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [182].Yang B, Liu H, Liu Z, Doenen R, Nash MA, Nano Lett 2020, 20, 8940–8950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [183].Tanrikulu IC, Schmitt E, Mechulam Y, Goddard WA, Tirrell DA, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2009, 106, 15285–15290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [184].Dieterich DC, Link AJ, Graumann J, Tirrell DA, Schuman EM, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2006, 103, 9482–9487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [185].Cheng Z, Kuru E, Sachdeva A, Vendrell M, Nat. Rev. Chem 2020, 4, 275–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [186].Budisa N, Pal PP, Biol. Chem 2004, 385, 893–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [187].Veettil S, Budisa N, Jung G, Biophys. Chem 2008, 136, 38–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [188].Hyun SL, Guo J, Lemke EA, Dimla RD, Schultz PG, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2009, 131, 12921–12923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [189].Chatterjee A, Guo J, Lee HS, Schultz PG, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2013, 135, 12540–12543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [190].Kalstrup T, Blunck R, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2013, 110, 8272–8277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [191].Wang J, Xie J, Schultz PG, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2006, 128, 8738–8739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [192].Sakata S, Jinno Y, Kawanabe A, Okamura Y, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2016, 113, E7866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [193].Wu Q, Schapira M, Arrowsmith CH, Barsyte-Lovejoy D, Nat. Rev. Drug Discov 2021, DOI 10.1038/s41573-021-00159-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [194].McDonough MA, Li V, Flashman E, Chowdhury R, Mohr C, Liénard BMR, Zondlo J, Oldham NJ, Clifton IJ, Lewis J, McNeill LA, Kurzeja RJM, Hewitson KS, Yang E, Jordan S, Syed RS, Schofield CJ, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2006, 103, 9814–9819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [195].Campolo N, Issoglio FM, Estrin DA, Bartesaghi S, Radi R, Essays Biochem 2020, 64, 111–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [196].Ahsan H, Hum. Immunol 2013, 74, 1392–1399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [197].Wu Y, Boxer SG, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 11890–11895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [198].Baumann T, Hauf M, Schildhauer F, Eberl KB, Durkin PM, Deniz E, Löffler JG, Acevedo-Rocha CG, Jaric J, Martins BM, Dobbek H, Bredenbeck J, Budisa N, Angew. Chemie - Int. Ed 2019, 58, 2899–2903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [199].Deniz E, Valiño-Borau L, Löffler JG, Eberl KB, Gulzar A, Wolf S, Durkin PM, Kaml R, Budisa N, Stock G, Bredenbeck J, Nat. Commun 2021, 12, 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]