Abstract

Objective

To assess the potential benefit of a behavioural change programme in working individuals with chronic pain or headache, in the form of increased physician consultation.

Design

Retrospective observational database study.

Setting

Members of employment-based healthcare insurance in Japan.

Participants

Individual-level data of working individuals aged <75 years from November 2019 through March 2020 were extracted from a database managed by MinaCare Co., Ltd. Included individuals had records of programme participation and chronic pain or headache (self-reported), and did not consult physicians for ≥3 months before programme participation.

Outcome measures

Physician consultation rates after participating in the programme were examined from December 2019 through March 2020, separately for chronic pain and headache. Baseline characteristics included age, pain numeric rating scale (NRS) score (for chronic pain), suspected migraine (for headache), labour productivity including absenteeism and presenteeism, and 4-month indirect costs in Japanese yen (JPY).

Results

The baseline mean age (±SD) of 506 individuals with chronic pain was 46.8±10.1 years; that of 352 individuals with headache was 43.6±9.9 years. Of those with chronic pain, 71.4% had an NRS score≥4, and 49.7% of those with headache had suspected migraine. Overall, 11.3% and 5.4% of those with chronic pain or headache consulted physicians, respectively. The mean baseline absenteeism and presenteeism were 1.5% and 19.1% in those with chronic pain, and 1.5% and 23.0% in those with headache. The baseline indirect costs were 586 941.6 JPY and 1 060 281.6 JPY among those with chronic pain or headache, respectively.

Conclusion

Given that the individuals did not regularly consult physicians before the programme despite reporting substantial symptoms, our results suggest the potential benefit of educational programmes encouraging physician consultation. Further studies are required to evaluate how to effectively implement such educational programmes via healthcare insurers to reduce the burden of pain symptoms and overall medical costs.

Keywords: Pain management, Back pain, Musculoskeletal disorders, Migraine

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The study used a nationwide database to estimate physician consultation rates among healthcare insurance members with chronic pain or headache after participating in an educational programme encouraging physician consultation.

The physician consultation rates and baseline characteristics were examined using data of insurance claims, health check-ups and questionnaires.

These results may not be generalisable, as the study population consisted of volunteer participants who were members of an employment-based healthcare insurance.

Introduction

Chronic pain and headache are common health conditions that impair physical function and psychological status. Although the reported prevalence in Japan is limited, chronic pain affects 15–39%1–3 of the nation’s population, and the prevalence is similar to that in the UK and the USA.4 5 Conversely, data regarding the prevalence of headache in Japan are unavailable (the global prevalence estimates of headache and migraine are 46% and 11%, respectively),6 but migraine affects 6–9%7–9 of the population in Japan. These estimates indicate a considerable burden of chronic pain and headache in Japan.

Evidence suggests that both chronic pain and headache have significant clinical, societal and labour productivity impacts. A study using the Japan National Health and Wellness Survey reported that respondents with chronic pain, including headache and migraine, had a lower mental and physical status, greater absenteeism, presenteeism, overall work impairment, and activity impairment, and higher indirect costs than those without.10 Other studies reported similar adverse effects of both chronic pain and headache on labour productivity.3 9 11

Despite these pieces of evidence, a large proportion of the Japanese population with chronic pain and headache do not seek medical services. For instance, 35–59% of individuals with chronic pain are untreated.2 10 12 Although some treated individuals select complementary and complementary medicine (ie, folk remedy) for their pain, only 22% were treated at hospitals/clinics.2 As for headache, 59–69% of individuals with migraine had never consulted physicians for their pain,8 9 and only 11.6% of people were aware of their migraine.8

MinaCare Co., Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan) (hereafter MinaCare) conducted a behavioural change programme to encourage working individuals with chronic pain and headache to seek medical services in cases where a medical consultation is required. The programme aimed to raise awareness of these health conditions and elicit medical consultations. Volunteer programme participants were provided with six-series educational information (eg, types of pain or headache, treatment options, and hospital information) via the Internet (online supplemental etable 1). Participants were also asked to respond to questionnaires regarding pain intensity, quality of life (QoL), and labour productivity. These response data were stored in the MinaCare database, which collates large-scale nationwide employment-based healthcare data.

bmjopen-2021-056846supp001.pdf (70.5KB, pdf)

Using this employment-based healthcare database and to formulate hypothesis, this retrospective, observational database study aimed to assess the potential benefit of the behavioural change programme in working individuals with chronic pain or headache, in the form of increased physician consultation. The physician consultation was assessed using healthcare claims data. The included individuals did not consult physicians for chronic pain or headache for the last 3 months before participating in the programme. We further described the patient characteristics, including labour productivity and indirect costs and exploratively examined factors associated with physician consultation using univariate logistic regressions.

Methods

Study design and data source

This retrospective, observational study used data from an employment-based healthcare database managed by MinaCare. The database population includes working individuals aged <75 years of large-scale nationwide corporations in Japan.

The database contained the following individual-level data: (1) annual health check-up data; (2) medical and pharmaceutical claims data; and (3) behavioural change programme data including participation records and questionnaire response data collected as a part of the behavioural change programme. The annual health check-up data included the demographics and smoking status from 2 079 250 individuals (as of October 2020). The healthcare claims data, collected since 2010, contained records from approximately 6.0 million people (as of 2019), representing 4.3% of the total insured individuals in Japan. The behavioural change programme data extracted for understanding baseline characteristics including labour productivity were available at the time of programme participation from November to December 2019.

Patient and public involvement

There was no patient or public involvement in the design, analysis or reporting of this study.

Study population

We extracted data on individuals who were members of employment-based healthcare insurance from November 2019 through March 2020. Eligible individuals had a participation record of the behavioural change programme and self-reported pain (primarily pain in any body parts excluding headache, or primarily headache) lasting for ≥3 months before programme participation (thereafter chronic pain or headache). Some individuals experienced both chronic pain and headache. To ensure that the included individuals had chronic pain, we included those with a pain numeric rating scale (NRS) score ≥1. We further excluded individuals who consulted physicians because of pain within 3 months before the programme. Physician consultation due to pain for individuals with chronic pain was defined as the presence of (1) diagnosis record(s) of pain (according to the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th revision code: M00–99 or R52) and (2) physical therapy record(s) (receipt category code: H002-00) or (3) anti-inflammatory or analgesic treatment record(s) (receipt category code: J119-00) from September 2019 to November 2019. This 3-month period was selected because the maximum prescription period is 90 days in Japan, and that of analgesics (such as opioids) is even shorter. For individuals with headache, physician consultation due to headache was defined as (1) diagnosis record(s) of headache (G43–44 or R51) and (2) anti-inflammatory or analgesic treatment record(s) (receipt category code: J119-00) during the same period.

Outcome measure

We examined the proportion of programme participants who consulted physicians for pain or headache (as defined above) after participating in the programme from December 2019 through March 2020, separately for those with chronic pain or headache. Participants joined the programme primarily in December 2019.

Baseline characteristics

We extracted the following baseline data at the time of programme participation (ie, December 2019): age, sex and history of continuous physician consultation for symptoms other than pain within 6 months before participation. These data were extracted from the medical and pharmaceutical claims data. The body mass index (BMI; <18.5, underweight; 18.5–<25, normal; 25–<30, pre-obese; 30–<35, obese class I; 35–<40, obese class II; ≥40, obese class III) and smoking status were extracted from the 2018 health check-up data (the latest data at the time of December 2019). The duration of pain, workstyle and pain treatment were extracted from self-administered questionnaires used in the behavioural change programme (collected in December 2019).

We further extracted the following baseline data on pain, QoL and labour productivity from the self-administered questionnaire data. For individuals with chronic pain, the average pain intensity was represented by pain NRS scores (1–3, mild pain; 4–6, moderate pain; 7–10, severe pain) within 1 week before programme participation. The Self-reported Leeds Assessment of Neuropathic Symptoms and Signs (S-LANSS) score13 was used to define the presence of neuropathic pain within 1 week before participation. The S-LANSS score ranges from 0 to 24, and the score ≥12 was defined as pain of predominantly neuropathic origin and that of <12 as pain of not predominantly neuropathic origin. The health-related QoL was defined using the EuroQoL-5 Dimension 5-level (EQ-5D-5L)14 at the time of participation. The EQ-5D-5L assesses five dimensions (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression) on a 5-point scale and the visual analogue scale. The utility index 1 represents ‘perfect health’ and 0 represents ‘death’ for the Japanese population.15

Baseline labour productivity was represented by the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire-General Health (WPAI) during the last 7 days before programme participation. This six-item questionnaire measures work productivity impairment, based on the following four metrics: (1) percentage of work time missed in the last week due to health conditions (absenteeism); (2) percentage of impairment while working due to health conditions (presenteeism); (3) percentage of overall work impairment due to health conditions and (4) percentage of activity impairment due to health conditions.16

We further estimated the 4-month indirect and medical costs in Japanese yen (JPY). Indirect costs before programme participation (August 2019 through November 2019) were estimated, based on absenteeism, presenteeism and overall wages/salaries.17 The total 4-month indirect costs were estimated as 1 week of indirect costs multiplied by 16 weeks. The 1 week indirect costs were estimated based on the sum of (a) the number of hours missed in the past week from participation because of one’s health condition and (b) the number of hours of productivity loss missed in the past week from the participation because of health impairment while at work, subsequently multiplied by hourly wages. Total medical costs were estimated using the claims data and represented costs spent in the corresponding 4 months as indirect costs. This 4-month assessment period was chosen because physician consultation behaviour was also examined during 4 months.

For individuals with headache, baseline pain intensity was defined using the Migraine Disability Assessment Test (MIDAS) scores, which determine the disability level of daily activities in the last 3 months,18 before programme participation. This test consists of 5 questions and measures the number of days of activity limitations.18–20 The scores 0–10 represent minimal, mild, or infrequent disability; 11–20, moderate disability; and ≥21, severe disability.18 The presence or absence of suspected migraine in the last 3 months before the participation was determined using a four-item migraine screener (aggravation by routine physical activity or avoidance, nausea/stomach discomfort, photophobia, and osmophobia). Each item was scored on a 4-point scale (1, never; 2, rarely; 3, sometimes and 4, half of the time or more). Suspected migraine was defined as ≥2 items with scores of 3 or 4.21 Other variables examined for individuals with chronic pain were also examined for those with headaches.

Statistical analysis

Baseline characteristics were descriptively summarised with the mean and standard deviation (SD) or the median and IQR (the first and third quartiles {Q1, Q3}) for continuous variables, and with frequency and percentage for categorical variables. These variables were examined separately for overall individuals with chronic pain or headache and for those who did and did not consult physicians after programme participation. Two groups with and without physician consultation were compared using t-tests. The date of the first physician consultation was also visually examined; however, such information was unavailable for individuals who were dispensed drugs at visiting hospitals/clinics. For exploratory purposes, univariate logistic regression analyses were performed to examine the association between physician consultation and baseline characteristics. The analysis estimated odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (lower confidence limit {LCL}, upper confidence limit {UCL}). No imputation was performed for missing data. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS Release V.9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., North Carolina), with a significance level of a two-sided p-value <0.05, only for a reference because of limited data.

Results

We identified 57 330 individual records in the database from November 2019 through March 2020 (figure 1). Of these, 506 individuals with chronic pain and 352 individuals with headache were included in the analysis population.

Figure 1.

Study population for (A) chronic pain or (B) headache. NRS, numeric rating scale.

Baseline characteristics

Chronic pain

The mean±SD baseline age of the overall population with chronic pain was 46.8±10.1 years with a BMI 21.8±3.4 kg/m2, and women represented 54.7% of the overall population (tables 1 and 2). Most individuals were engaged in deskwork (41.5% for day shift and 19.6% for shift work), and 36.4% of individuals had shift work other than deskwork. The mean pain NRS score was 4.9±2.0, and 71.4% of individuals had moderate to severe pain with an NRS score≥4. The mean EQ-5D-5L utility score of the overall population was 0.8±0.1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of individuals with (A) chronic pain or (B) headache at baseline

| (A) Chronic pain | Overall | Physician consultation | No physician consultation | Pr > |t|* | |||

| (n=506) | (n=57) | (n=449) | |||||

| Characteristics | Missing n | Mean±SD or median (Q1, Q3) | Missing n | Mean±SD or median (Q1, Q3) | Missing n | Mean±SD or median (Q1, Q3) | |

| Age, years | – | 46.8±10.1 | – | 49.4±9.8 | – | 46.5±10.1 | 0.0433 |

| BMI†, kg/m2 | 42 | 21.8±3.4 | 11 | 22.5±3.8 | 31 | 21.7±3.4 | 0.1610 |

| Duration of pain, months | – | 116.6±122.9 | – | 116.9±146.3 | – | 116.5±119.8 | 0.9831 |

| Pain NRS | – | 4.9±2.0 | – | 5.1±2.0 | – | 4.9±2.0 | 0.4255 |

| EQ-5D-5L (Score) | – | 0.8±0.1 | – | 0.8±0.1 | – | 0.8±0.1 | 0.0008§ |

| EQ-5D-5L (VAS) | – | 66.9±18.5 | – | 64.8±20.6 | – | 67.2±18.2 | 0.3489 |

| WPAI (absenteeism), % | 10 | 1.5±8.4 | 3 | 0.7±2.8 | 7 | 1.6±8.8 | 0.4863 |

| WPAI (presenteeism), % | – | 19.1±19.5 | – | 14.6±18.0 | – | 19.7±19.6 | 0.0599 |

| WPAI (overall work impairment), % | 10 | 20.4±20.8 | 3 | 15.5±19.0 | 7 | 21.0±20.9 | 0.0690 |

| WPAI (activity impairment), % | – | 26.5±23.6 | – | 23.2±23.2 | – | 26.9±23.7 | 0.2544 |

| Indirect cost‡, JPY | – | 586 941.6 (0.0, 1 622 208.0) | – | 100 979.2 (0.0, 1 405 913.6) | – | 608 328.0 (0.0, 1 640 912.0) | 0.1507 |

| Medical cost‡, JPY | – | 15 545.0 (0.0, 42 810.0) | – | 24 370.0 (6 980.0, 54 390.0) | – | 14 890.0 (0.0, 40 020.0) | 0.0102 |

| (B) Headache | Overall | Physician consultation | No physician consultation | Pr > |t|* | |||

| (n=352) | (n=19) | (n=333) | |||||

| Characteristics | Missing n | Mean±SD or median (Q1, Q3) | Missing n | Mean±SD or median (Q1, Q3) | Missing n | Mean±SD or median (Q1, Q3) | |

| Age, years | – | 43.6±9.9 | – | 47.3±5.8 | – | 43.3±10.0 | 0.0878 |

| BMI†, kg/m2 | 27 | 21.4±3.2 | 1 | 22.2±2.4 | 26 | 21.3±3.3 | 0.2816 |

| Duration of pain, months | – | 169.7±136.3 | – | 234.2±172.7 | – | 166.0±133.3 | 0.0339 |

| MIDAS | – | 10.0±12.8 | – | 10.8±8.4 | – | 10.0±13.0 | 0.7903 |

| EQ-5D-5L (Score) | – | 0.9±0.1 | – | 0.8±0.1 | – | 0.9±0.1 | 0.2600 |

| EQ-5D-5L (VAS) | – | 68.9±18.0 | – | 65.8±16.6 | – | 69.0±18.1 | 0.4500 |

| WPAI (absenteeism), % | 8 | 1.5±5.7 | – | 4.1±8.0 | 8 | 1.4±5.5 | 0.0436 |

| WPAI (presenteeism), % | – | 23.0±21.6 | – | 24.7±22.9 | – | 22.9±21.5 | 0.7203 |

| WPAI (overall work impairment), % | 8 | 24.0±22.1 | – | 27.4±24.3 | 8 | 23.8±21.9 | 0.4856 |

| WPAI (activity impairment), % | – | 27.9±23.9 | – | 29.5±25.9 | – | 27.8±23.8 | 0.7678 |

| Indirect cost‡, JPY | – | 1 060 281.6 (0.0, 1 946 649.6) | – | 1 186 505.6 (473 144.0, 2 524 480.0) | – | 1 060 281.6 (0.0, 1 893 360.0) | 0.2495 |

| Medical cost‡, JPY | – | 18 470.0 (5 455.0, 43 340.0) | – | 42 660.0 (19 710.0, 71 160.0) | – | 17 150.0 (5 390.0, 41 310.0) | 0.0960 |

*The t-text was used for two groups of physician consultation and no physician consultation.

†BMI was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in metres.

‡Indirect and medical costs represented costs incurred during 4 months from August 2019 through November 2019.

§The mean EQ-5D-5L (Score) and (SD) with three decimal point was 0.765 (0.140) and 0.818 (0.106).

BMI, body mass index; EQ-5D-5L, EuroQoL-5 Dimension 5-level; JPY, Japanese yen; MIDAS, migraine disability assessment test; NRS, numeric rating scale; Q1, first quartile; Q3, third quartile; SD, standard deviation; VAS, visual analogue scale; WPAI, work productivity and activity impairment questionnaire.

Table 2.

Characteristics at baseline and OR of physician consultation among individuals with (A) chronic pain or (B) headache

| (A) Chronic pain | Overall | Physician consultation | No physician consultation | DF | OR (LCL to UCL) | P-value |

| (n=506) | (n=57) | (n=449) | ||||

| Characteristics | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |||

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 229 (45.3) | 32 (56.1) | 197 (43.9) | - | 1 | - |

| Female | 277 (54.7) | 25 (43.9) | 252 (56.1) | 1 | 0.61 (0.35 to 1.06) | 0.082 |

| Age, years | ||||||

| <40 | 119 (23.5) | 10 (17.5) | 109 (24.3) | - | 1 | - |

| 40–59 | 341 (67.4) | 40 (70.2) | 301 (67.0) | 1 | 1.45 (0.70 to 3.00) | 0.318 |

| ≥60 | 46 (9.1) | 7 (12.3) | 39 (8.7) | 1 | 1.96 (0.70 to 5.50) | 0.203 |

| Type of workstyle | ||||||

| Day shift, deskwork | 210 (41.5) | 21 (36.8) | 189 (42.1) | - | 1 | - |

| Shift work, deskwork | 99 (19.6) | 6 (10.5) | 93 (20.7) | 1 | 0.58 (0.23 to 1.49) | 0.257 |

| Day shift, other than deskwork | 13 (2.6) | 3 (5.3) | 10 (2.2) | 1 | 2.70 (0.69 to 10.59) | 0.154 |

| Shift work, other than deskwork | 184 (36.4) | 27 (47.4) | 157 (35.0) | 1 | 1.55 (0.84 to 2.84) | 0.159 |

| Pain treatment | ||||||

| Self-stretch or self-massage | 330 (65.2) | 30 (52.6) | 300 (66.8) | 1 | 0.55 (0.32 to 0.96) | 0.036 |

| Exercise | 136 (26.9) | 11 (19.3) | 125 (27.8) | 1 | 0.62 (0.31 to 1.24) | 0.174 |

| Self-meditation or self-mindfulness | 9 (1.8) | 0 (0.0) | 9 (2.0) | - | - | - |

| Gym | 77 (15.2) | 5 (8.8) | 72 (16.0) | 1 | 0.50 (0.19 to 1.30) | 0.158 |

| Massage therapy | 107 (21.1) | 9 (15.8) | 98 (21.8) | 1 | 0.67 (0.32 to 1.42) | 0.296 |

| Stretch therapy | 15 (3.0) | 1 (1.8) | 14 (3.1) | 1 | 0.56 (0.07 to 4.30) | 0.573 |

| Physical therapy | 72 (14.2) | 7 (12.3) | 65 (14.5) | 1 | 0.83 (0.36 to 1.90) | 0.655 |

| OTC drugs | 97 (19.2) | 10 (17.5) | 87 (19.4) | 1 | 0.89 (0.43 to 1.82) | 0.741 |

| Nothing | 52 (10.3) | 4 (7.0) | 48 (10.7) | 1 | 0.63 (0.22 to 1.82) | 0.394 |

| Others | 22 (4.3) | 3 (5.3) | 19 (4.2) | 1 | 1.26 (0.36 to 4.39) | 0.719 |

| Smoking status | ||||||

| No | 408 (80.6) | 40 (70.2) | 368 (82.0) | - | 1 | - |

| Yes | 51 (10.1) | 6 (10.5) | 45 (10.0) | 1 | 1.23 (0.49 to 3.05) | 0.661 |

| Missing | 47 (9.3) | 11 (19.3) | 36 (8.0) | - | - | - |

| Pain NRS | ||||||

| 1–3 (mild pain) | 145 (28.7) | 14 (24.6) | 131 (29.2) | - | 1 | - |

| 4–6 (moderate pain) | 225 (44.5) | 29 (50.9) | 196 (43.7) | 1 | 1.38 (0.71 to 2.72) | 0.345 |

| 7–10 (severe pain) | 136 (26.9) | 14 (24.6) | 122 (27.2) | 1 | 1.07 (0.49 to 2.34) | 0.858 |

| Neuropathic pain (S-LANSS score) | ||||||

| <12 | 487 (96.2) | 53 (93.0) | 434 (96.7) | - | 1 | - |

| ≥12 (predominantly neuropathic origin) | 19 (3.8) | 4 (7.0) | 15 (3.3) | 1 | 2.18 (0.70 to 6.82) | 0.179 |

| Obesity (BMI*, kg/m2) | ||||||

| <18.5 (underweight) | 71 (14.0) | 4 (7.0) | 67 (14.9) | 1 | 0.50 (0.17 to 1.47) | 0.211 |

| 18.5–<25 (normal) | 302 (59.7) | 32 (56.1) | 270 (60.1) | - | 1 | - |

| 25–<30 (pre-obese) | 78 (15.4) | 8 (14.0) | 70 (15.6) | 1 | 0.96 (0.43 to 2.19) | 0.931 |

| 30–<35 (obese class I) | 10 (2.0) | 1 (1.8) | 9 (2.0) | 1 | 0.94 (0.12 to 7.64) | 0.952 |

| 35–<40 (obese class II) | 3 (0.6) | 1 (1.8) | 2 (0.5) | 1 | 4.22 (0.37 to 47.84) | 0.245 |

| ≥40 (obese class III) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | - | - | - |

| Missing | 42 (8.3) | 11 (19.3) | 31 (6.9) | - | - | - |

| History of continuous physician consultation for symptoms other than pain within 6 months before program participation | ||||||

| No | 249 (49.2) | 26 (45.6) | 223 (49.7) | - | 1 | - |

| Yes | 257 (50.8) | 31 (54.4) | 226 (50.3) | 1 | 1.18 (0.68 to 2.05) | 0.565 |

| (B) Headache | Overall | Physician consultation | No physician consultation | DF | OR (LCL to UCL) | P-value |

| (n=352) | (n=19) | (n=333) | ||||

| Characteristics | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |||

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 111 (31.5) | 7 (36.8) | 104 (31.2) | - | 1 | - |

| Female | 241 (68.5) | 12 (63.2) | 229 (68.8) | 1 | 0.78 (0.30 to 2.03) | 0.609 |

| Age, years | ||||||

| <40 | 122 (34.7) | 1 (5.3) | 121 (36.3) | - | 1 | - |

| 40–59 | 220 (62.5) | 18 (94.7) | 202 (60.7) | 1 | 10.78 (1.42 to 81.79) | 0.021 |

| ≥60 | 10 (2.8) | 0 (0.0) | 10 (3.0) | - | - | - |

| Type of workstyle | ||||||

| Day shift, deskwork | 147 (41.8) | 9 (47.4) | 138 (41.4) | - | 1 | - |

| Shift work, deskwork | 78 (22.2) | 4 (21.1) | 74 (22.2) | 1 | 0.83 (0.25 to 2.78) | 0.761 |

| Day shift, other than deskwork | 8 (2.3) | 0 (0.0) | 8 (2.4) | - | - | - |

| Shift work, other than deskwork | 119 (33.8) | 6 (31.6) | 113 (33.9) | 1 | 0.81 (0.28 to 2.36) | 0.705 |

| Pain treatment | ||||||

| Self-stretch or self-massage | 161 (45.7) | 6 (31.6) | 155 (46.6) | 1 | 0.53 (0.20 to 1.43) | 0.209 |

| Exercise | 40 (11.4) | 2 (10.5) | 38 (11.4) | 1 | 0.91 (0.20 to 4.11) | 0.906 |

| Self-meditation or self-mindfulness | 7 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (2.1) | - | - | - |

| Gym | 43 (12.2) | 3 (15.8) | 40 (12.0) | 1 | 1.37 (0.38 to 4.92) | 0.626 |

| Massage therapy | 74 (21.0) | 6 (31.6) | 68 (20.4) | 1 | 1.80 (0.66 to 4.91) | 0.252 |

| Stretch therapy | 8 (2.3) | 2 (10.5) | 6 (1.8) | 1 | 6.41 (1.20 to 34.16) | 0.03 |

| Physical therapy | 38 (10.8) | 3 (15.8) | 35 (10.5) | 1 | 1.60 (0.44 to 5.75) | 0.475 |

| OTC drugs | 236 (67.0) | 11 (57.9) | 225 (67.6) | 1 | 0.66 (0.26 to 1.69) | 0.386 |

| Nothing | 22 (6.3) | 1 (5.3) | 21 (6.3) | 1 | 0.83 (0.11 to 6.49) | 0.855 |

| Others | 20 (5.7) | 1 (5.3) | 19 (5.7) | 1 | 0.92 (0.12 to 7.25) | 0.935 |

| Smoking status | ||||||

| No | 295 (83.8) | 17 (89.5) | 278 (83.5) | - | 1 | - |

| Yes | 29 (8.2) | 1 (5.3) | 28 (8.4) | 1 | 0.58 (0.08 to 4.55) | 0.608 |

| Missing | 28 (8.0) | 1 (5.3) | 27 (8.1) | - | - | - |

| MIDAS | ||||||

| 0–10 (minimal, mild, or infrequent disability) | 236 (67.0) | 10 (52.6) | 226 (67.9) | - | 1 | - |

| 11–20 (moderate disability) | 59 (16.8) | 6 (31.6) | 53 (15.9) | 1 | 2.56 (0.89 to 7.35) | 0.081 |

| ≥21 (severe disability) | 57 (16.2) | 3 (15.8) | 54 (16.2) | 1 | 1.26 (0.33 to 4.72) | 0.736 |

| Suspected migraine | ||||||

| Absent | 177 (50.3) | 6 (31.6) | 171 (51.4) | - | 1 | - |

| Presence | 175 (49.7) | 13 (68.4) | 162 (48.7) | 1 | 2.29 (0.85 to 6.16) | 0.102 |

| Obesity (BMI*, kg/m2) | ||||||

| <18.5 (underweight) | 59 (16.8) | 0 (0.0) | 59 (17.7) | - | - | - |

| 18.5–<25 (normal) | 212 (60.2) | 16 (84.2) | 196 (58.9) | - | 1 | - |

| 25–<30 (pre-obese) | 47 (13.4) | 2 (10.5) | 45 (13.5) | 1 | 0.54 (0.12 to 2.45) | 0.429 |

| 30–<35 (obese class I) | 7 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (2.1) | - | - | - |

| 35–<40 (obese class II) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | - | - | - |

| ≥40 (obese class III) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | - | - | - |

| Missing | 27 (7.7) | 1 (5.3) | 26 (7.8) | - | - | - |

| History of continuous physician consultation for symptoms other than pain within 6 months before program participation | ||||||

| No | 150 (42.6) | 3 (15.8) | 147 (44.1) | - | 1 | - |

| Yes | 202 (57.4) | 16 (84.2) | 186 (55.9) | 1 | 4.22 (1.21 to 14.74) | 0.024 |

* BMI was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in meters.

BMI, body mass index; DF, degree of freedom; LCL, lower control limit; MIDAS, migraine disability assessment test; NRS, numeric rating scale; OR, odds ratio; OTC, over-the-counter; S-LANSS, Self-reported Leeds Assessment of Neuropathic Symptoms and Signs; UCL, upper control limit.

Headache

The mean baseline age of the overall population with headache was 43.6±9.9 years with a BMI 21.4±3.2 kg/m2, and women represented 68.5% (tables 1B and 2B). Similar to chronic pain, most individuals were engaged in deskwork (41.8% for day shift and 22.2% for shift work), and 33.8% were engaged in shift work other than deskwork. The mean MIDAS score was 10.0±12.8, and 67.0% had minimal, mild, or infrequent disability (score 0–10), while 16.8% and 16.2% had moderate (11–20) and severe (≥21) disability. Suspected migraine was found in 49.7% of the overall population. The mean EQ-5D-5L utility score was 0.9±0.1.

Physician consultation

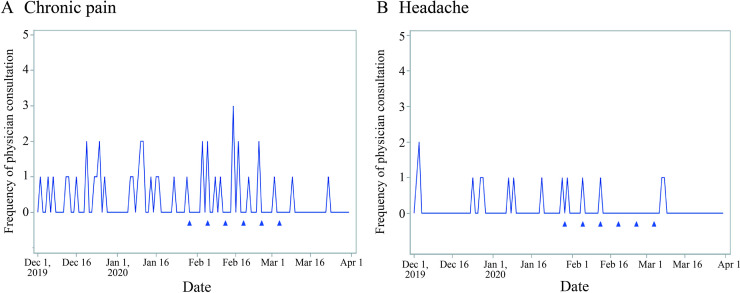

The proportion of individuals who consulted physicians after participating in the programme was 11.3% (57/506 individuals) for chronic pain and 5.4% (19/352 individuals) for headache. Although clear patterns were not observed because a small number of individuals consulted physicians, the first consultation was observed in December before the educational content was released for both individuals with chronic pain and headache (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Timing of the first physician consultation due to pain among individuals with (A) chronic pain or (B) headache. Triangles represent the date when a series of six educational contents were released to participating members via email. The figures include individuals whose date of the first physician consultation was identified in the database. The data could not be identified in the database for those who were dispensed analgesics at visiting hospitals/clinics (ie, not at the pharmacy), and thus, they are not included in these figures.

Labour productivity, indirect costs and medical costs

Chronic pain

The mean baseline absenteeism, presenteeism, overall work impairment and activity impairment among individuals with chronic pain were 1.5±8.4%, 19.1±19.5%, 20.4±20.8% and 26.5±23.6%, respectively. The median (Q1, Q3) total 4-month indirect costs, estimated based on absenteeism and presenteeism, were 586 941.6 JPY (0.0, 1 622 208.0), and medical costs were 15 545.0 JPY (0.0, 42 810.0).

Headache

The mean baseline absenteeism, presenteeism, overall work impairment and activity impairment among individuals with headache were 1.5±5.7%, 23.0±21.6%, 24.0±22.1%, and 27.9±23.9%, respectively. The median total 4-month indirect and medical costs were 1 060 281.6 JPY (0.0, 1 946 649.6) and 18 470.0 JPY (5 455.0, 43 340.0).

Baseline characteristics among individuals who did and did not consult physicians

Chronic pain

The mean baseline age of individuals with chronic pain was 49.4±9.8 years and 46.5±10.1 years among those who did and did not consult physicians, respectively, and women were slightly less represented in the former group (43.9%) than the latter group (56.1%) (tables 1A and 2A). Individuals with pain of predominantly neuropathic origin represented 7.0% of individuals who consulted physicians and 3.3% of those who did not. The total 4-month indirect costs were 100 979.2 JPY (0.0, 1 405 913.6) and 608 328.0 JPY (0.0, 1 640 912.0) for individuals who did and did not consult physicians, respectively. The median total 4-month medical costs were 24 370.0 JPY (6 980.0, 54 390.0) and 14 890.0 JPY (0.0, 40 020.0) for individuals who did and did not consult physicians, respectively.

Headache

The mean baseline age of individuals with headache was 47.3±5.8 years and 43.3±10.0 years among those who did and did not visit physicians, and women were less represented in the former group (63.2%) than in the latter group (68.8%) (tables 1B and 2B). The median total 4-month indirect costs were 1 186 505.6 JPY (473 144.0, 2 524 480.0) and 1 060 281.6 JPY (0.0, 1 893 360.0) for individuals who did and did not consult physicians, respectively. The median total 4-month medical costs were 42 660.0 JPY (19 710.0, 71 160.0) and 17 150.0 JPY (5 390.0, 41 310.0) for individuals who did and did not consult physicians, respectively.

Factors associated with physician consultation

The exploratory univariate logistic regression model showed that the odds of physician consultation were lower among individuals with chronic pain who self-stretched and self-massaged at baseline than those who did not (OR=0.55 {LCL, UCL: 0.32 to 0.96}; table 2A). The odds of physician consultation were higher among individuals with headaches aged 40 to 59 years than those who are younger (OR=10.78 {1.42 to 81.79}; table 2B). The odds of physician consultation were higher among individuals who received stretch therapy at baseline or those who continuously consulted physicians for symptoms other than pain within 6 months before programme participation than those who did not (OR=6.41 {1.20 to 34.16} and 4.22 {1.21 to 14.74}, respectively).

Discussion

This database study, conducted using an employment-based healthcare database, found that 11.3% and 5.4% of individuals with chronic pain and headache, respectively, consulted physicians after participating in the behavioural change programme. As the included individuals did not consult physicians for ≥3 months before programme participation despite some of them reporting substantial pain (3.8% with pain of predominantly neuropathic origin for individuals with chronic pain) and had moderate to severe disability (33.0% for headache) and suspected migraine (49.7% for headache), they were not supposed to change their behaviour easily. Further research evaluating the benefit of such educational programmes on behavioural change is awaited. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to report physician consultation rates among individuals with chronic pain or headache who participated in an educational programme encouraging consultation.

It was previously reported that only 22% of individuals with chronic pain were treated at hospitals/clinics, and 35–59% were left untreated.2 10 12 As chronic pain affects 15–39% of people in Japan,1–3 a substantial number of Japanese people with chronic pain may be untreated. As for headache, only 2.7% and 1.3% of individuals and workers with migraine, respectively, regularly consulted physicians.8 9 Considering these reports, 5–11% of consultation rates after participating in the programme were unexpectedly high. We, however, could not evaluate the programme’s effect on physician consultation behaviour. Further studies are needed to evaluate causality.

Our results suggest that the continuous provision of educational information may encourage an increased number of individuals to seek medical services. Additionally, as some individuals consulted physicians before receiving educational content, programme participation itself may have influenced their behaviour. As pain is expected to improve in some individuals treated by physicians, such programmes may be both clinically and societally beneficial. For example, in a previous study, 68% of individuals with chronic pain reported that their pain was improved by treatments including the use of medication.2 As pain and its greater intensity are associated with a lower QoL, greater absenteeism and presenteeism,2 3 9–12 improvements in pain may also lead to improvements in these domains. In addition, the provision of such educational information may be a trigger for raising awareness of one’s health conditions. In our study, approximately half of the individuals with headache had suspected migraine, although whether they were aware of their migraine is unknown. As previously reported, only 11.6% of individuals with migraine are aware of their migraine8; therefore, such provision may be especially beneficial as the first step in managing this clinical condition.

Baseline presenteeism, overall work impairment and activity impairment were higher than absenteeism in individuals with both chronic pain and headache, which is consistent with the findings of previous Japanese studies.10 22 Our results indicate that presenteeism, work productivity loss and activity impairment, rather than absenteeism, may be related to pain in Japan, as reported by Tsujii et al.22 Although absenteeism among workers with chronic pain may be easily noticed at the workplace as employees take time off, presenteeism may be under-noticed. If companies and employers aim to increase productivity, monitoring presenteeism and providing additional support to workers with chronic pain and headache could lead to improvement in labour productivity. Further studies may explore the reason for higher presenteeism. For instance, presenteeism has been previously reported to be associated with contextual reasons (eg, work demands and organisational policies) as well as individual reasons (eg, personality and work ethics).23 Work absence attributable to musculoskeletal pain (eg, low back pain, neck pain, and shoulder pain) was much lower in Japanese workers24 than in those in UK.25 Cultural differences may have influenced these results.

The baseline 4-month indirect costs were six times higher among individuals with chronic pain who did not consult physicians than among those who did so (median costs, 608 328.0 JPY {equivalent to 5 776.68 US$} and 100 979.2 JPY {958.90 US$}, respectively; an exchange rate on November 11, 2020). This difference was not observed for headache. Although the reason for these high indirect costs is unknown, the potential negative effects on labour productivity suggest that the productivity of companies is adversely affected and should raise alarms to employers. The indirect costs of chronic pain were generally similar to those previously reported.10

Limitations

This study has several limitations. Causality between the programme and physician consultation behaviour could not be evaluated due to the non-interventional design, and further research is awaited. Our results may not be generalisable to the general working population in Japan for the following reasons. First, health check-up and claims data were obtained from employment-based health insurers. The age distribution of our study population, however, was generally similar to that of workers in Japan, but due to the employment-based nature of the database, those aged >60 years were less represented in our study than the general working population.26 Women were slightly more represented in our study than the general working population,26 but this sex ratio is reasonable considering that more women are generally affected by these clinical conditions than men.2 3 7 9 Second, these health insurers cover employees of large-scale nationwide corporations, and the study populations may be more educated and well-paid than the general working population. Third, we examined existing data that were collected from volunteers, and healthy or health-conscious individuals are more likely to participate in such health programmes. However, the percentage of individuals with a history of physician consultation before programme participation was similar to that reported by Nakamura et al. (22.0%).2 No data were available for headache. There are also limitations to the database. The medical costs estimated based on claims data did not include other costs associated with pain (eg, over-the-counter drugs) and could, therefore, be underestimated. Some variables such as the NRS and WPAI asked about past conditions or events, and measured variables may contain errors. As some individuals would underestimate past conditions or events while others overestimate, measured variables are not expected to contain systematic errors.

Conclusion

In this retrospective study using an employment-based healthcare database, we found that 5–11% of individuals with chronic pain or headache consulted physicians for pain treatment after participating in a behavioural change programme. Given that none of the individuals had consulted physicians for ≥3 months prior to participating in the programme despite some of them experiencing substantial pain, such consultation rates may suggest potential benefits of an educational programme on physician consultation. Such benefits may be both clinically and societally significant. Further studies are required to evaluate the causality and how to effectively implement such educational programmes via healthcare insurers (including means of information delivery) to reduce the burden of pain symptoms and overall medical costs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Statistical analysis and medical writing were supported by Clinical Study Support, Inc. and both were funded by Viatris Pharmaceuticals Japan Inc.

Footnotes

Contributors: KN and SM conceived and designed the study and designed the analysis of the data. KN and SM interpreted results, drafted the first manuscript and critically revised and edited the manuscript. SH, YY and YA conceived and designed the study and designed the analysis of the data. SH, YY and YA interpreted results and critically revised and edited the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work. SM acts as a guarantor for this study.

Funding: This work was funded by Viatris Pharmaceuticals Japan Inc. The funder was involved in the study design, analysis, interpretation of data, the writing of the report, decision to publish and preparation of the manuscript. Award/Grant number is not applicable.

Competing interests: KN, SM, SH and YA are employees of Viatris Pharmaceuticals Japan Inc.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data may be obtained from a third party and are not publicly available. The dataset supporting the findings of this study is available from MinaCare Co., Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan), independent of Viatris Pharmaceuticals Japan Inc., who is not involved in validating or storing the data analysed in this study. Restrictions apply to the availability of the data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available; data are, however, available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission from MinaCare Co., Ltd.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

This study used existing data stored in an anonymised structured format and contained no personal information. Obtaining informed consent from the participants and approval from an ethical review committee were not required, because studies using only unlinkable anonymised data are outside the scope of ‘Ethical Guidelines for Medical and Health Research Involving Human Subjects’ set by the Japanese government. The study was conducted in accordance with legal and regulatory requirements (eg, privacy protection laws) as well as with scientific purpose, value and rigour. MinaCare manages such anonymised data under a data transfer contract with its client health insurers.

References

- 1.Ogawa S, lseki M. Kikuchi S. a large-scale survey on chronic pain and neuropathic pain in Japan. Clinical Orthopaedic Surgery 2012;47:565–74. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nakamura M, Nishiwaki Y, Ushida T, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of chronic musculoskeletal pain in Japan. J Orthop Sci 2011;16:424–32. 10.1007/s00776-011-0102-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Inoue S, Kobayashi F, Nishihara M, et al. Chronic pain in the Japanese Community—Prevalence, characteristics and impact on quality of life. PLoS One 2015;10:e0129262. 10.1371/journal.pone.0129262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fayaz A, Croft P, Langford RM, et al. Prevalence of chronic pain in the UK: a systematic review and meta-analysis of population studies. BMJ Open 2016;6:e010364. 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dahlhamer J, Lucas J, Zelaya C, et al. Prevalence of Chronic Pain and High-Impact Chronic Pain Among Adults - United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018;67:1001–6. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6736a2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stovner LJ, Hagen K, Jensen R, et al. The global burden of headache: a documentation of headache prevalence and disability worldwide. Cephalalgia 2007;27:193–210. 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2007.01288.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takeshima T, Ishizaki K, Fukuhara Y, et al. Population-Based door-to-door survey of migraine in Japan: the Daisen study. Headache 2004;44:8–19. 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2004.04004.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sakai F, Igarashi H. Prevalence of migraine in Japan: a nationwide survey. Cephalalgia 1997;17:15–22. 10.1046/j.1468-2982.1997.1701015.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Suzuki N, Ishikawa Y, Gomi S, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of headaches in a socially active population working in the Tokyo metropolitan area -surveillance by an industrial health Consortium. Intern Med 2014;53:683–9. 10.2169/internalmedicine.53.1700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takura T, Ushida T, Kanchiku T, et al. The societal burden of chronic pain in Japan: an Internet survey. J Orthop Sci 2015;20:750–60. 10.1007/s00776-015-0730-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wada K, Moriyama M, Narai R, et al. [The effect of chronic health conditions on work performance in Japanese companies]. Sangyo Eiseigaku Zasshi 2007;49:103–9. 10.1539/sangyoeisei.49.103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sadosky AB, DiBonaventura M, Cappelleri JC, et al. The association between lower back pain and health status, work productivity, and health care resource use in Japan. J Pain Res 2015;8:119–30. 10.2147/JPR.S76649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bennett MI, Smith BH, Torrance N, et al. The S-LANSS score for identifying pain of predominantly neuropathic origin: validation for use in clinical and postal research. J Pain 2005;6:149–58. 10.1016/j.jpain.2004.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Herdman M, Gudex C, Lloyd A, et al. Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L). Qual Life Res 2011;20:1727–36. 10.1007/s11136-011-9903-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ikeda S, Shiroiwa T, Igarashi A. Developing a Japanese version of the EQ-5D-5L value set. J Natl Inst Public Health 2015;64:47–55. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reilly MC, Zbrozek AS, Dukes EM. The validity and reproducibility of a work productivity and activity impairment instrument. Pharmacoeconomics 1993;4:353–65. 10.2165/00019053-199304050-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Welfare MoHLa . Wage and labour welfare statistics: office employment, basic survey on wage structure. Tokyo 2014.

- 18.Iigaya M, Sakai F, Kolodner KB, et al. Reliability and validity of the Japanese migraine disability assessment (MIDAS) questionnaire. Headache 2003;43:343–52. 10.1046/j.1526-4610.2003.03069.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stewart WF, Lipton RB, Kolodner KB, et al. Validity of the migraine disability assessment (MIDAS) score in comparison to a diary-based measure in a population sample of migraine sufferers. Pain 2000;88:41–52. 10.1016/S0304-3959(00)00305-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stewart WF, Lipton RB, Dowson AJ, et al. Development and testing of the migraine disability assessment (MIDAS) questionnaire to assess headache-related disability. Neurology 2001;56:S20–8. 10.1212/WNL.56.suppl_1.S20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takeshima T, Sakai F, Suzuki N. A simple migraine screening instrument: validation study in Japan. Cephalalgia 2015;42:134–43. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tsuji T, Matsudaira K, Sato H, et al. Association between presenteeism and health-related quality of life among Japanese adults with chronic lower back pain: a retrospective observational study. BMJ Open 2018;8:e021160. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-021160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johns G. Presenteeism in the workplace: a review and research agenda. J Organ Behav 2010;31:519–42. 10.1002/job.630 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matsudaira K, Palmer KT, Reading I, et al. Prevalence and correlates of regional pain and associated disability in Japanese workers. Occup Environ Med 2011;68:191–6. 10.1136/oem.2009.053645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Madan I, Reading I, Palmer KT, et al. Cultural differences in musculoskeletal symptoms and disability. Int J Epidemiol 2008;37:1181–9. 10.1093/ije/dyn085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Statistics Bereau of Japan Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications . Summary of the latest yearly average results 2020. Available: https://www.stat.go.jp/data/roudou/sokuhou/nen/ft/pdf/index1.pdf [Accessed October 14 2020].

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2021-056846supp001.pdf (70.5KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data may be obtained from a third party and are not publicly available. The dataset supporting the findings of this study is available from MinaCare Co., Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan), independent of Viatris Pharmaceuticals Japan Inc., who is not involved in validating or storing the data analysed in this study. Restrictions apply to the availability of the data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available; data are, however, available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission from MinaCare Co., Ltd.