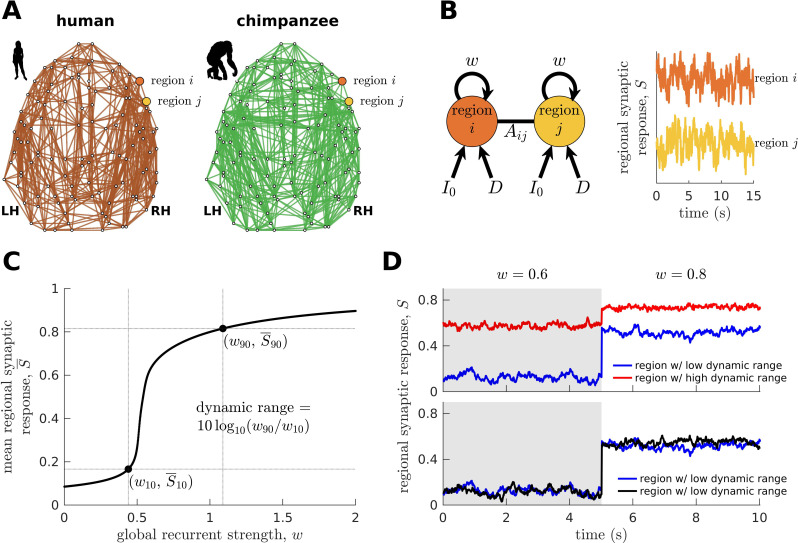

Figure 2. Brain network modeling.

(A) Group-averaged human and chimpanzee networks visualized on the same brain template. Top 20% of connections by strength are shown. (B) Schematic diagram of the model. Each brain region is recurrently connected with strength and driven by an excitatory input and white noise with standard deviation . The connection between regions and is weighted by based on the connectomic data. The regional neural dynamics are represented by the synaptic response variable ; high translates to high neural activity. (C) Method for calculating the dynamic range of each brain region from its mean synaptic response versus global recurrent strength curve. Note that , with being the corresponding global recurrent strength at and . (D) Example time series of regions with different (top panel) and similar (bottom panel) dynamic ranges at = 0.6 and 0.8. The time series in the top panel have correlation values (Pearson’s r) of 0.06 and 0.08 at = 0.6 and = 0.8, respectively. The time series in the bottom panel have correlations of 0.40 and 0.14 at = 0.6 and = 0.8, respectively.