Abstract

Background

The COVID-19 pandemic exerted profound effects on parents, which may translate into elevated child abuse risk. Prior literature demonstrates that Social Information Processing theory is a useful framework for understanding the cognitive processes that can contribute to parental abuse risk, but the model has not adequately integrated affective processes that may coincide with such cognitions.

Objective

Given parents experienced intense emotions during the pandemic, the current study sought to examine how socio-emotional processes might account for abuse risk during the pandemic (perceived pandemic-related increases in harsh parenting, reported physical and psychological aggression, and child abuse potential).

Participants and methods

Using two groups of mothers participating in online studies, the combined sample of 304 mothers reported on their abuse risk and cognitive and anger processes.

Results

Greater approval of physical discipline and weaker anger regulation abilities were directly or indirectly related to measures of abuse risk during the pandemic, with maternal justification to use parent-child aggression to ensure obedience consistently relating to all indicators of abuse risk during the pandemic.

Conclusions

Socio-emotional processes that include anger appear particularly relevant during the heightened period of strain induced by the pandemic. By studying multiple factors simultaneously, the current findings can inform child abuse prevention efforts.

Keywords: Coronavirus, Physical child abuse risk, Child abuse potential, Psychological aggression, Social information processing theory, Emotion

1. Introduction

Whereas physical child abuse involves intentional physical force that results in child injury, psychological abuse incurs mental harm to the child (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [DHHS], 2022), with observed parallels between both forms of maltreatment (Kim et al., 2017; Rodriguez & Richardson, 2007; Spinazzola et al., 2014). Statistics based on official reports of these forms of child maltreatment are routinely considered the “tip of the iceberg” due to substantial underreporting (Sedlak et al., 2010; Stoltenborgh et al., 2015). Consequently, rather than be limited by reliance on official reports, alternative approaches attempt to estimate a parent's child abuse risk by inquiring about their beliefs and behaviors that presage child maltreatment (Bavolek & Keene, 2001; Chaffin & Valle, 2003). Child abuse risk is based on a conceptualization of physical or psychological aggression as operating along a parent-child aggression (PCA) continuum of severity and intensity (Gershoff, 2010; Rodriguez, 2021; Straus, 2000, Straus, 2001). Parents who use familiar forms of physical or psychological PCA (e.g., spanking, yelling) at the earlier end of the spectrum are at elevated risk of escalating to abusive PCA further along this spectrum (Afifi et al., 2017; Durrant et al., 2009; Gershoff & Grogan-Kaylor, 2016; King et al., 2018) wherein use of any form of PCA increases parents' risk of child abuse.

Unfortunately, the COVID-19 pandemic appears to have amplified the underreporting problem that typically accompanies child maltreatment prevalence estimates (Brown et al., 2021; Musser et al., 2021; Rapoport et al., 2021; Whelan et al., 2021), which will likely underestimate the scope of child abuse that transpired during the pandemic. At its outset, concerns emerged about the potential avenues for the pandemic to heighten child maltreatment risk. For example, persistent and episodic economic strain and financial hardship are well established contributors to elevated levels of maltreatment risk, and research confirmed that millions of American parents were struggling due to job and income loss (Gassman-Pines & Gennetian, 2020). One of the most robust conclusions drawn from the pandemic-related research is that many Americans experienced elevated levels of depression and anxiety, particularly in the early days of the pandemic (American Psychological Association, 2020; Lee, Ward, Chang, et al., 2021; Twenge & Joiner, 2021). Required social isolation guidelines may have weakened the social networks that buffer parents' harsh parenting practices (Lee, Ward, Lee, et al., 2021). Factors such as household and parenting stress (Connell & Strambler, 2021; Rodriguez, Lee, Ward, & Pu, 2021), unemployment (Lawson et al., 2020; Rodriguez, Lee, Ward, & Pu, 2021), exposure to other forms of family violence such as IPV (Humphreys et al., 2020), and social isolation (Bullinger et al., 2020; Lee, Ward, Lee, et al., 2021; Sinko et al., 2021) each contributed to elevated child abuse risk during the pandemic. Indeed, studies demonstrated high levels of harsh parenting during the pandemic (Connell & Strambler, 2021; Sari et al., 2021), with elevated abuse risk and psychological aggression observed even after controlling for pre-pandemic levels (Rodriguez, Lee, Ward, & Pu, 2021).

Although research has investigated contextual factors (e.g., economic, parenting stress, and mental health) that increased child abuse risk during the pandemic, to date, research has not adequately delved into the underlying parental socio-cognitive processes that might contribute to such elevated abuse risk. Clarifying the mechanisms that prompt parents to engage in PCA is critical to inform child abuse prevention efforts in general, but during times like the pandemic public health crisis, quick identification of key contributors becomes more pressing. One theory has been proposed to describe the socio-cognitive processes whereby parents become abusive—referred to as Social Information Processing (SIP) theory (Milner, 2000). SIP theory contends that parents hold preconceived beliefs (e.g., pre-existing schemas about discipline and parenting) developed over time before they even encounter a parent-child conflict that initiates a discipline response. When conflict then arises, SIP theory postulates a series of stages wherein the parent may misperceive the situation (Stage 1), formulate negative interpretations and expectations (Stage 2), and fail to incorporate potentially mitigating information for the child's behavior or consider their non-aggressive response options (Stage 3), leading to PCA (Milner, 2000).

Empirical research has identified that pre-existing beliefs approving of physical discipline are a precursor for PCA (Lansford et al., 2014; McCarthy et al., 2016; Rodriguez et al., 2011; Smith Slep & O'Leary, 2007). Furthermore, parents who hold negative child intent attributions (an SIP Stage 2 process) evidence greater abuse risk (Azar et al., 2013; Berlin et al., 2013; Camilo et al., 2020; Rodriguez et al., 2012, Rodriguez et al., 2020). Another cognition that may relate to parents' SIP Stage 2 interpretations during parent-child conflict is rarely examined in the literature—namely, whether a parent justifies PCA use during conflict. Recent work suggests parents may justify PCA because they wish to instill obedience (Rodriguez, Lee, & Ward, 2021), consistent with early work on mothers' justifications for discipline (Kelley et al., 1992), although this potential SIP Stage 2 process is seldom examined. Parents with less knowledge of alternatives to physical discipline (a potential SIP Stage 3 element) are also more inclined to engage in PCA (Camilo et al., 2020; Rodriguez et al., 2016), which is reflected in prevention programs that emphasize psychoeducation about positive discipline practices (Durrant et al., 2014; Prinz et al., 2009).

Although the SIP model applied to child abuse risk predominantly focuses on parents' socio-cognitive processing (Camilo et al., 2020; Rodriguez, Silvia et al., 2019), the original formulation did recognize the theoretical importance of considering emotion and negative affect (Milner, 2000). The SIP model for child aggression has incorporated emotion (e.g., Lemerise & Arsenio, 2000), and a recent systematic review examined the extant research on emotion (viz. anger and emotion regulation) in concert with SIP processes in aggressive behavior (Smeijers et al., 2020). Yet this review identified no prior research linking emotion and SIP processing specifically with regard to PCA, suggesting a significant gap in knowledge related to how emotion may intersect with SIP processes in parent-child conflict. Recent work has implicated parent emotions may contribute to the SIP model of child abuse risk broadly (Rodriguez, Lee, & Ward, 2021; Rodriguez et al., 2022), but these connections specifically for child abuse risk remain underdeveloped.

Additionally, the unique conditions arising from COVID-19 are underexplored in relation to parental emotion and SIP processes. The COVID-19 pandemic has precipitated significant emotional distress, signaling that parents' emotion could be central to understanding their abuse risk during this public health crisis. One of the key emotions believed to elevate child abuse risk involves parental anger (Hien et al., 2010; Rodriguez, 2018; Smith Slep & O'Leary, 2007; Stith et al., 2009), and thus was our focus in this study. Parents may not regulate negative affect effectively, with ample evidence that poor frustration tolerance and emotion regulation contribute to greater abuse risk (Hien et al., 2010; Hiraoka et al., 2016; Rodriguez et al., 2017). Together, we propose a clearer integration of emotion into the SIP model to reflect a Socio-Emotional Information Processing (SEIP) model specifically for PCA that more clearly centers emotion within the model (cf. Rodriguez, Lee, & Ward, 2021; Rodriguez & Lee, 2022), which may expand to include emotions beyond anger. The anxiety and strain many parents encountered during the pandemic has been documented but how they have experienced and regulated their anger and frustration has not, particularly in concert with their cognitions. Adults reported elevated anger and frustration during the pandemic (American Psychological Association, 2020) and examining its role appears particularly relevant to understanding pandemic-related child abuse risk.

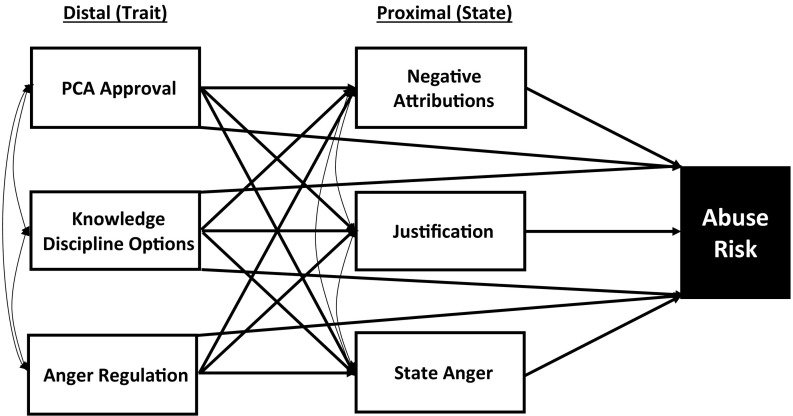

Notably, empirically testing such SEIP processes as a sequential model—as if elements unfold in true stages wherein one stage is completed before another stage commences—is unrealistic even using longitudinal designs. Parent cognitions and emotions during parent-child conflict likely transpire synchronously (see Crick & Dodge, 1994, for their early recognition that SIP processes during aggression are unlikely to be rigid, linear sequences). Thus, the premise of “stages” arising in discipline encounters is largely theoretical. An alternative conceptualization is to view distal “trait” characteristics as temporally preceding parent-child conflict episodes, whereas proximal “state” factors would be those that arise when faced with parent-child conflict. For the present investigation, we thus theorized that parents' distal trait-like characteristics would temporally predate proximal state processes which would then predict maternal abuse risk. We designated pre-existing schema approving of PCA, knowledge of alternatives to PCA, and the ability to regulate anger as distal, parental “trait” qualities developed over time that precede parent-child conflict. Pre-existing schemas like PCA approval have typically been viewed as preceding the SIP stages (Milner, 2000), but knowledge of discipline options has been construed as a Stage 3 SIP process to be accessed to inform response to child behavior; however, knowledge of discipline options is likely to be distal to parent-child conflict situations, remaining relatively static without active psychoeducation. The ability to regulate anger is not formally considered in the SIP model but characterizes the parent themselves, independent of the child, and thus trait-like and distal. In contrast, negative child intent attributions and justification for PCA because of obedience (often viewed as SIP Stage 2 processes) as well as state anger were all considered proximal “state” qualities that would arise in response to a specific perceived parent-child conflict situation—factors we proposed as the possible mechanisms whereby the distal “trait” qualities would elevate mothers' child abuse risk.

Thus, the current study examined socio-emotional information processing to clarify what may contribute to mothers' elevated abuse risk during the COVID-19 pandemic. We integrated both state anger and anger control into an SEIP model in an effort to deepen our understanding of how anger processes relate to commonly investigated SIP cognitions. SEIP factors considered pre-existing, distal trait qualities (attitudes approving of PCA as a discipline approach; ability to control and regulate anger; knowledge of discipline options) were hypothesized to predict outcomes (child abuse potential; physical and psychological PCA; perceived changes in harsh parenting during COVID-19) in part mediated by more proximal state-like SEIP factors pertaining directly to parent-child conflict (negative child intent attributions; state anger; discipline justification); we controlled for COVID-19 related employment financial loss and socioeconomic status as potentially relevant to the pandemic (see Fig. 1 for hypothesized model). We tested a model with three measures of abuse risk to avoid reliance on a single measure that may not replicate given the replicability crisis in science (Wiggins & Christopherson, 2019), enhancing our ability to identify robust contributors to PCA risk during the pandemic.

Fig. 1.

Hypothesized path model predicting abuse risk (pandemic-related perceived changes in harsh parenting, physical and psychological parent-child aggression, and child abuse potential).

2. Method

2.1. Participants and procedures

The current sample (N = 304) included two groups of mothers. The first subsample (n = 110) involved mothers enrolled in the “Following First Families” (Triple-F) study, a prospective longitudinal study tracking parent-child aggression risk across the transition to parenthood in the Southeast U.S. First-time mothers and their partners were recruited in their last trimester with flyers distributed to eligible participants at local hospitals' ob/gyn clinics and childbirth classes; interested mothers contacted the lab and enrolled in the three-wave Triple-F study. Given that the primary local hospital provides community prenatal health services, half of these families demonstrated one or more sociodemographic risk factors (i.e., ≤150 % of the federal poverty line, receipt of federal assistance, ≤high school education, single parenthood, ≤age 18). In an extension of the Triple-F study, mothers were re-invited in the early part of the pandemic, during six weeks from end of May to June 2020, to report on their parenting using an online survey (via Qualtrics). At that point, their children would have been between ages 5–6 ½ years old. The university's Institutional Review Board approved all study procedures.

The second subsample (n = 194) was recruited to expand the pool of participants beyond the Southeast; this national sample was comprised of mothers responding to a Qualtrics survey in late September 2020 delivered through Prolific, an online survey research and data collection company (Palan & Schitter, 2018). Prolific sent the survey to all eligible participants and organized participant compensation, allowing responses to remain anonymous, and the survey automatically closed when a predetermined sample size was reached. Eligibility criteria were set to approximate the Triple-F study: age ≥ 18 years; mother of a child age 8 or younger; US nationality. Mothers provided consent prior to completing the survey. To affirm data quality, responses were screened for duplicates and three attention check items were interspersed in the protocol, with no mother missing more than one check. Because the data are de-identified from Prolific, the university Institutional Review Board deemed this study exempt from oversight.

In order to collapse across samples, we conducted initial analyses to confirm that the two subsamples were comparable on key characteristics. These analyses indicated that the two subsamples were comparable on maternal age, ethnicity, racial composition, living with a spouse/partner, receipt of public assistance, annual household income, and educational attainment and the subsamples attained comparable scores across all three dependent variables (all p > .15). Given their similarity, the two groups were combined (N = 304).

For this combined sample, mothers' mean age was 32.70 years (SD = 5.77). Mothers selected the racial group with which they predominantly identify: 55.6 % of mothers identified as White; 43.1 % as Black. 0.7 % as Asian, and 0.7 % as Native American or Alaskan; 8.9 % also identified as multiracial and 3.6 % as Hispanic. In terms of mothers' educational level: 13.8 % ≤ high school; 25.3 % some college; 29.6 % college degree; 31.3 % ≥ college degree. In terms of combined household income, 23.1 % reported an annual household income below $30,000, 47.2 % reported a household income below $60,000; 29.9 % of the sample reported receipt of public assistance; 81.9 % reported currently living with a spouse or partner.

2.2. Measures

All primary measures appear in Table 1 along with current study reliability statistics where appropriate. Mothers were asked to respond to questions focused on their most challenging child. Mothers also reported on whether they or their partner had experienced a change in employment due to the pandemic: previously unemployed, laid-off/furloughed, reduced hours, working from home, or no change. COVID-19 related employment financial loss was dichotomized as no financial change (unemployed pre-pandemic, no change, or working from home) versus employment loss suggesting financial impact (laid off or reduced hours).

Table 1.

Measures by construct with descriptions.

| Construct/measure | Description |

|---|---|

| Proposed distal trait variables | |

| PCA approval | |

| Attitudes toward Spanking Scale (ATS; Holden, 2001) | 10-item measure of attitudes toward physical discipline, 7-point scale (1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree), hi scores = greater PCA approval; prior support from reliability and predictive validity (Ateah & Durrant, 2005); current study α = .94 |

| Knowledge of discipline options | |

| Production of Discipline Alternatives (PDA; Rodriguez, Wittig, et al., 2019) | Open-ended question for last PCV vignette (see below); mother types all possible discipline responses they can think of; 2 coders categorize each response as physical, nonphysical, or psychological; # nonphysical or physical options generated are averaged between coders (ICC = .98); proportion scores control for more total options (total physical options ÷ total options); hi scores = proportionately more physical options generated; demonstrates reliability, high stability, and concurrent and predictive validity |

| Anger regulation | |

| State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory (STAXI; Spielberger, 1988) | Frequently used measure for experience and expression of anger; 8-item Anger Control subscale extracted for this study involving perceived, trait (stable) ability to control anger; items use 4-point scale (1 = almost never to 4 = almost always); hi scores = stronger anger control; current study α = .87 |

| Proposed proximal state variables (mediators) | |

| Negative child attributions | |

| Plotkin Child Vignettes (PCV Attribution; Plotkin, 1983; Haskett et al., 2006) | 18 vignettes of child misbehavior; 9-point scale on perception of child intention (1 = did not mean to annoy me at all to 9 = only reason the child did this was to annoy me); summed across vignettes, hi scores = more negative attributions; reliability, validity evidence from abusive mothers (Haskett et al., 2006); current study α = .91 |

| State anger | |

| Plotkin Child Vignettes-Anger (PCV-Angerl; Rodriguez et al., 2022) | After each PCV vignette, how angry they would feel on a 9-point scale (1 = not angry or frustrated at all to 9 = very angry or frustrated), hi scores = more anger/frustration; current study α = .92 |

| Justification | |

| Parent-Child Conflict Tactics Scale (Straus et al., 1998), Justify Obedience (Rodriguez, Lee, Ward, 2021a) | After each CTSPC item endorsed for either physical or psychological PCA (see below), mother asked to think of last time she used that PCA and select all reasons (multiple selections allowed): “you wanted your child to learn values”; “you wanted your child to learn to obey”, “you were angry or frustrated”; this study tallied the number of selections of obedience across tactics (possible range 0–18) |

| Dependent variables (DV) | |

| Adult Adolescent Parenting Inventory-2 (AAPI-2; Bavolek & Keene, 2001) | Child abuse potential measure of beliefs characteristic of abusive parenting; 40 items rated on 5-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree); summed across items, hi scores = greater abuse risk; current study α = .93 |

| Parent-Child Conflict Tactics Scale (CTSPC; Straus et al., 1998), Combined Assault | Frequently used measure of PCA use including 22 items on discipline tactics use during pandemic; 18-item Combined Assault score computed as weighted frequency counts from 13-item Physical Assault subscale plus 5-item Psychological Aggression subscale; hi scores = more frequent use of physical and psychological PCA |

| Pandemic-related perceived changes in parenting (Lee, Ward, Lee, et al., 2021; Rodriguez, Lee, Ward, & Pu, 2021) | Responses to three pandemic questions related to abuse risk: “Since the coronavirus/COVID-19 global health crisis began,” 5-point scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree): “I have spanked or hit my child more often than usual”, “I have yelled at/screamed at my child more than usual”, “I have used harsh words toward my child more than usual”; summed across items, hi = harsher parenting; current study α = .75 |

2.3. Analytic plan

Preliminary analyses were performed with SPSS 27.0. Path models considered the three outcomes simultaneously (child abuse potential; physical and psychological PCA; pandemic-related perceived changes in harsh parenting), as depicted in Fig. 1. Path analyses utilized Mplus 8.1 with missing values accommodated using full-information maximum likelihood methods (FIML) (<1.5 % missing data). Testing for indirect effects was conducted using the Mplus “Model Indirect” command with 500 bootstraps. Because we fully controlled our models to focus on path coefficients, our models were fully identified and model fit indices are uninformative. Results below provide findings using maternal reports of justification for PCA to teach obedience (for reader interest, comparable findings using maternal reports of justification to use PCA because of anger or frustration are provided in Supplemental Table S1).

3. Results

3.1. Preliminary analyses

Means and standard deviations for each measure along with their intercorrelations appear in Table 2 . Because household income and educational level were highly correlated (r = .60, p < .001), both were standardized and combined into a composite SES score. Of the full sample, 37.8 % had experienced COVID-19 employment financial loss in their household. The path analysis controlled for both SES and COVID-19 related employment financial loss.

Table 2.

Means, standard deviations, and correlations among outcome measures.

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. PCA approval | |||||||||

| 2. Knowledge options | .44⁎⁎⁎ | ||||||||

| 3. Anger regulation | −.09 | −.17⁎⁎ | |||||||

| 4. Negative attributions | .23⁎⁎⁎ | .32⁎⁎⁎ | −.20⁎⁎⁎ | ||||||

| 5. State anger | .21⁎⁎⁎ | .28⁎⁎⁎ | −.28⁎⁎⁎ | .67⁎⁎⁎ | |||||

| 6. Justification | .46⁎⁎⁎ | .28⁎⁎⁎ | −.13⁎ | .24⁎⁎⁎ | .23⁎⁎⁎ | ||||

| 7. AAPI-2 | .67⁎⁎⁎ | .39⁎⁎⁎ | −.19⁎⁎⁎ | .52⁎⁎⁎ | .31⁎⁎⁎ | .42⁎⁎⁎ | |||

| 8. CTSPC combined | .39⁎⁎⁎ | .36⁎⁎⁎ | −.20⁎⁎⁎ | .21⁎⁎⁎ | .31⁎⁎⁎ | .52⁎⁎⁎ | .35⁎⁎⁎ | ||

| 9. COVID-19 combined | .27⁎⁎⁎ | .24⁎⁎⁎ | −.37⁎⁎⁎ | .21⁎⁎⁎ | .29⁎⁎⁎ | .38⁎⁎⁎ | .31⁎⁎⁎ | .53⁎⁎⁎ | |

| Mean | 36.43 | .13 | 24.97 | 43.48 | 2.62 | 60.09 | 95.89 | 31.60 | 5.76 |

| SD | 16.37 | .24 | 4.96 | 21.60 | 2.32 | 23.73 | 23.10 | 32.01 | 2.70 |

Note. PCA = parent-child aggression; AAPI-2 = Adult-Adolescent Parenting Inventory-2; CTSPC Combined = Parent-Child Conflict Tactics Scale, Physical Assault and Psychological Aggression Combined; COVID-19 Combined = Pandemic-related perceived changes in parenting, combined physical and psychological PCA.

p ≤ .05.

p ≤ .01.

p ≤ .001.

3.2. Trait-state pathways

Results from the path model are presented in Table 3 with standardized coefficients and standard errors. Greater PCA approval was associated with more negative attributions and higher obedience justification. Less knowledge of alternatives to physical discipline was associated with more negative attributions and higher state anger. Finally, better anger regulation was associated with less negative attributions and lower state anger.

Table 3.

Standardized coefficients for AAPI-2, CTSPC combined assault, and COVID-19 perceived change in parenting.

|

Direct effects |

||

|---|---|---|

| β (SE) | p | |

| PCA Approval ➔ Attribution | .12(0.06) | .032 |

| PCA Approval ➔ State Anger | .11(0.06) | .053 |

| PCA Approval ➔ Justification | .47(0.05) | <.001 |

| Knowledge ➔ Attribution | .23(0.08) | .003 |

| Knowledge ➔ State Anger | .19(0.06) | .002 |

| Knowledge ➔ Justification | .04(0.07) | .514 |

| Anger Regulation ➔ Attribution | −.14(0.05) | .010 |

| Anger Regulation ➔ State Anger | −.24(0.06) | <.001 |

| Anger Regulation ➔ Justification | −.06(0.05) | .278 |

| AAPI-2 |

CTSPC |

COVID-Comb |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β (SE) | p | β (SE) | p | β (SE) | p | |

| PCA Approval ➔ DV | .54(0.04) | <.001 | .05(0.07) | .419 | .05(0.06) | .460 |

| Knowledge ➔ DV | .01(0.03) | .896 | .18(0.06) | .004 | .07(0.07) | .312 |

| Anger Regulation ➔ DV | −.08(0.05) | .088 | −.08(0.05) | .104 | −.29(0.06) | <.001 |

| Attribution ➔ DV | .47(0.06) | <.001 | −.08(0.07) | .243 | −.04(0.08) | .645 |

| State Anger ➔ DV | −.15(0.05) | .004 | .18(0.07) | .014 | .13(0.08) | .111 |

| Justification ➔ DV | .10(0.05) | .047 | .44(0.07) | <.001 | .28(0.06) | <.001 |

| Indirect Effects | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCA Approval ➔ Attribution ➔ DV | .06(0.03) | .037 | −.01(0.01) | .365 | .00(0.01) | .696 |

| PCA Approval ➔ State Anger ➔ DV | −.02(0.01) | .114 | .02(0.01) | .157 | .01(0.01) | .272 |

| PCA Approval ➔ Justification ➔ DV | .05(0.02) | .055 | .20(0.04) | <.001 | .13(0.03) | <.001 |

| Knowledge ➔ Attribution ➔ DV | .11(0.04) | .006 | −.02(0.02) | .292 | −.01(0.02) | .671 |

| Knowledge ➔ State Anger ➔ DV | −.03(0.01) | .047 | .03(0.02) | .071 | .02(0.02) | .161 |

| Knowledge ➔ Justification ➔ DV | .01(0.01) | .556 | .02(0.03) | .525 | .01(0.02) | .540 |

| Anger Regulation ➔ Attribution ➔ DV | −.07(0.03) | .015 | .01(0.01) | .309 | .00(0.01) | .674 |

| Anger Regulation ➔ State Anger ➔ DV | .04(0.02) | .022 | −.04(0.02) | .045 | −.03(0.02) | .171 |

| Anger Regulation ➔ Justification ➔ DV | −.01(0.01) | .403 | −.03(0.02) | .266 | −.02(0.02) | .264 |

Note. PCA = parent-child aggression. DV = dependent variable, which refers to: AAPI-2 = Adult-Adolescent Parenting Inventory-2; CTSPC = Parent-Child Conflict Tactics Scale, Physical Assault and Psychological Aggression Combined; COVID-19 Comb = Pandemic-related perceived changes in parenting. All models control for SES and COVID-related employment financial loss. Bolded values denote statistical significance; italicized values are only marginally significant at p < .07.

3.3. Direct and indirect effects to dependent variables

COVID-19-related employment financial loss was not a significant predictor for any of the outcomes. In predicting AAPI-2 scores, greater PCA approval was directly associated with higher abuse potential, as were more negative child intent attributions and obedience justifications (but lower state anger). The indirect effects suggested greater PCA approval was indirectly related to higher AAPI-2 scores through heightened negative attributions (only marginally through greater obedience justification). Further, less knowledge of alternatives and poorer anger regulation were associated with abuse potential through more negative child attributions. But less knowledge of discipline and poorer anger regulation were also indirectly related with higher abuse potential through lower state anger. These unexpected inverse effects for state anger are likely a statistical artifact because negative attributions featured prominently with the AAPI-2 while state anger shares measurement variance with negative attributions.

Regarding reports of more PCA use (CTSPC Combined Assault), less knowledge of alternatives to physical discipline, more obedience justifications and higher state anger were associated with reports of more PCA use. Indirect effects also suggested that greater PCA approval was indirectly related to higher PCA use through heightened obedience justification. Lower anger regulation (and marginally, less knowledge of discipline alternatives) was associated with more frequent PCA use via greater state anger.

Finally, mothers' perceived harsher parenting during the COVID-19 pandemic was directly associated with lower anger regulation and more obedience justifications. Higher PCA approval was also associated with harsher parenting during the pandemic via more obedience justification.

4. Discussion

The current investigation evaluated whether Social Information Processing theory that incorporates anger into a Socio-Emotional Information Processing (SEIP) model would account for increased abuse risk during the COVID-19 pandemic. This study also included maternal justification for using PCA, a potential SIP process that has rarely been considered. Viewing the elements of the SEIP model as distal (“trait”) versus proximal (“state”), the state-like factors that would arise during discipline episodes (negative child intent attributions; state anger; justification) were expected to mediate distal trait-like factors (which pre-date discipline events: PCA approval, anger regulation ability, knowledge of discipline options) and indicators of child abuse risk during the pandemic (pandemic-related perceived change in harsh parenting; physical and psychological PCA use; child abuse potential). Greater PCA approval, weaker anger control abilities, and less knowledge of non-physical discipline options (all three distal qualities) were significantly related to negative child intent attributions. Further, greater PCA approval was significantly related to mothers' justification of PCA to ensure obedience; poorer anger control abilities and less knowledge of discipline options were both related to greater state anger. Justification of PCA for obedience was a proximal factor consistently directly related to all indicators of abuse risk during the pandemic. A number of indirect effects also accounted for the relation between the distal factors and greater abuse risk.

Consistent with the growing body of research documenting the importance of PCA approval attitudes as a precursor for elevated child abuse risk (Camilo et al., 2020; Lansford et al., 2014; McCarthy et al., 2016; Rodriguez et al., 2020), the current investigation demonstrated direct or indirect effects from attitudes endorsing PCA as a discipline approach. The findings suggest that greater approval directly contributes to increased risk on one of the traditional measures of child abuse risk (AAPI-2) and indirectly through obedience justification for all three measures of abuse risk during the pandemic. Indeed, greater PCA approval also indirectly related to the AAPI-2 measure through negative child intent attributions. Note that the AAPI-2 measure in particular weighs PCA approval heavily. Although a direct effect was not observed for PCA approval on PCA use or perceived change in harsh parenting during the pandemic, both of those outcome measures did demonstrate indirect effects and both outcome measures included psychological PCA which is not captured in the measure of physical PCA approval, potentially obscuring direct effects (see Limitations below). With the direct and indirect effects, not only do our findings collectively underscore the prerequisite role PCA approval attitudes may play in contributing to child abuse risk, they also highlight the overlooked role of parental justification in contributing to abuse risk given that obedience justification also mediated the link from PCA approval to abuse risk across all three outcome measures.

Rather than conceptualizing such mediation models in causal terms, what this model illustrates is that part of the connection between PCA approval and elevated abuse risk appears to be because mothers justify PCA to ensure obedience. Delineating such indirect mechanisms is meaningful practically because they reveal the importance of not only modifying parents' PCA approval attitudes but potentially parents' expectations for obedience to justify their PCA use as well. Notably, PCA approval did not exert direct effects on COVID-19 change in adverse parenting nor on the CTSPC but only indirectly through justification; such indirect path models can thus illuminate relations that may be obscured when considering only direct effects. Parents' justifications for their use of PCA have been rarely studied (Kelley et al., 1992; Rodriguez, Lee, & Ward, 2021), but may be an important cognitive process that underlies aggressive behavior (e.g., Borrajo et al., 2015; Calvete & Orue, 2012; Diaz-Aguado & Martinez, 2015). Apparently, more research is warranted delving into how parents justify their actions in parent-child conflict as such internal justifications conceivably serve to reinforce parents' subsequent use of PCA.

The current findings on the connection between negative child intent attributions and abuse risk are partially consistent with prior research (Azar et al., 2013; Berlin et al., 2013; Haskett et al., 2006), including earlier work that has observed negative attributions serving as a mediator (Rodriguez et al., 2020). In the present study, negative child attributions consistently related to all three distal variables, although only exerted both direct and indirect effects for one of the measures of abuse risk during the pandemic (AAPI-2). Practitioners and researchers should thus be aware that the AAPI-2 appears particularly sensitive to negative child intent attributions, in effect emphasizing PCA approval and negative attributions above obedience justification in a manner not observed for the other two measures. In these highly controlled statistical models that account for shared variance among variables, negative attributions were not as salient nor consistent an SIP cognitive interpretation relative to the consistency and strength observed for obedience justification—which demonstrated direct effects robust across outcome measures. During the pandemic, mothers were spending increased time with children while also experiencing increased demands from schooling their children or working from home. Perhaps the strains induced by the pandemic led mothers to prioritize a need for quick obedience rather than to deliberate about the motivations behind their children's behavior. Future work clearly needs to consider incorporating both SIP Stage 2 cognitive appraisals simultaneously to determine their differential links with abuse risk.

The associations observed for knowledge of discipline options were nuanced. Prior research has implied that parents who do not consider non-physical discipline options evidence greater abuse risk (Camilo et al., 2020; Rodriguez et al., 2016). In the current study, less knowledge of discipline options was related to reported state anger at children's perceived misbehavior. Although direct effects were observed for less knowledge of options on reported increased PCA use during the pandemic (CTSPC, the most behaviorally indexed outcome measure), some evidence emerged that less knowledge of options exerted an indirect influence on abuse risk through negative attributions (AAPI-2) and marginally through greater state anger (CTSPC). Such findings support continued psychoeducational efforts to inform parents of their positive discipline options (e.g., Durrant et al., 2014; Gershoff & Lee, 2020; Prinz et al., 2009). However, knowledge of non-physical discipline was not directly or indirectly related to mothers' perceived change in harsh parenting due to the pandemic. Perhaps this null effect reflects that mothers—cognitively overloaded by the pandemic—were not contemplating discipline alternatives; instead, perceived changes in their parenting were more strongly linked to anger, which featured more prominently with that outcome. Comprehensive models such as the current test highlight that, when considered simultaneously, knowledge of non-physical alternatives to discipline would be insufficient on its own to curb PCA.

Overall, the current findings reinforce the proposition that emotions like anger be more fully integrated into SIP models (e.g., Lemerise & Arsenio, 2000; Milner, 2000; Rodriguez & Pu, 2020; Smeijers et al., 2020) to include those applied to parent-child conflict. Mothers' poor anger regulation abilities or state anger played a pronounced role across outcomes during the pandemic, either directly or indirectly. Poor anger control related directly to more perceived adverse parenting during the pandemic and indirectly to PCA use through increased state anger. Prior work has demonstrated anger plays a role in parents' harsh discipline and abuse risk (Ateah & Durrant, 2005; Hien et al., 2010; Rodriguez, 2018; Smith Slep & O'Leary, 2007; Stith et al., 2009). The paradoxical finding that lower state anger mediated the link between less knowledge of discipline options and poorer anger control with a traditional measure of abuse risk (AAPI-2) likely reflects the shared method variance of state anger and negative attributions, with attributions dominating so forcefully in predicting AAPI-2 scores in a manner not reflected in the other two outcome measures.

Given anger appeared notable in all models, SIP theory as applied to PCA may need to be reframed in favor of a Socio-Emotional Information Processing model. Because the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated mental health issues for many Americans (American Psychological Association, 2020; Lee, Ward, Chang, et al., 2021; Twenge & Joiner, 2021), mothers' emotions may be highly salient during this time, potentially amplifying the role anger played in this study. Indeed, surveys indicate that anger and frustration were elevated during the pandemic (American Psychological Association, 2020). Future work will need to replicate whether anger indeed relates to this number of cognitive processes when the pandemic abates. Furthermore, the proposed model focused on anger, but additional work needs to consider models with other emotional responses during parent-child conflict (e.g., anxiety; cf. Rodriguez & Lee, 2022; Rodriguez, Lee, & Ward, 2021) to better clarify the role of emotions in the SEIP model.

4.1. Limitations and future directions

A number of limitations should be acknowledged. The cross-sectional design limits causal inferences, and thus the direction of effects cannot be ascertained (notwithstanding the statistical language of direct and indirect effects). In theoretical models where multiple factors essentially transpire instantaneously and concurrently, causal modeling is complicated. Our proposed mediating factors were viewed as specific to parent-child conflict situations, assigning temporal precedence to distal factors as predating such mediators. However, assessing the distal factors as dispositional qualities at an earlier time point within a longitudinal design would be ideal.

Additionally, the measure utilized for PCA approval focuses exclusively on physical PCA approval, not combined physical and psychological PCA. This could reduce its direct effects on the measure of perceived change in harsh parenting as well as PCA use (CTSPC) during the pandemic—both outcomes measures that included psychological PCA. This serves as a reminder that a measure of parents' approval of using psychological PCA is not available. Separate measurement of state anger and negative child intent attributions would also be ideal given that shared instrument variance can obscure the unique effects of either factor within a single model.

Our sample only included mothers, although fathers have also experienced hardships during the pandemic (e.g., Kerr et al., 2021; Patrick et al., 2020). Future research should consider potential differences in SEIP factors that may distinguish fathers from mothers. Furthermore, our specific sample evidenced limited variability in child age although child maltreatment rates do vary by age (DHHS, 2022); thus, future work should consider how these SEIP processes may affect child abuse risk across a wider child age range. Our study surveyed mothers relatively early in the pandemic, which may not capture whether mothers have acclimated to the pandemic conditions over time. Moreover, we did not have data available on all of the studied constructs pre-pandemic to be able to compare our findings, and the data relied on maternal reports. Continued work will thus also need to probe how our findings may be unique to the pandemic era and consider incorporating more objective measures of these constructs.

We considered SES and pandemic-induced financial loss as covariates as a reflection of the background context for potential child abuse risk, but these qualities could also represent moderators. Other moderating effects from the parental environment should also be examined, such as the effect of stressors from intimate partner violence as well as mental health concerns, like depression and substance use, which could serve to exacerbate SEIP processes; in contrast, other moderating effects, such as coping and social support, could serve to mitigate abuse risk. Additional research should also gauge other potential interaction effects, specifically investigating racial and ethnic group differences given recent work suggesting SEIP factors may operate differently by racial group (Rodriguez, Lee, & Ward, 2021), and abundant evidence of the disproportionate impact of the pandemic on communities of color (Sneed et al., 2020) who already face sustained systemic obstacles.

5. Implications and conclusions

The current study highlights the applicability of socio-emotional processes as factors that relate to maternal abuse risk during the pandemic. From an intervention standpoint, a key result of this study is that parental approval of PCA, maternal justification for PCA, and knowledge of discipline options were related to abuse risk—all elements that could be addressed through structured parent interventions (Gershoff & Lee, 2020). Given the apparently overlooked role of justification, evidence-based practices such as motivational interviewing can be utilized to examine mothers' justifications for their use of PCA, pairing those beliefs with psychoeducation on alternative forms of discipline to reframe attitudes toward PCA (Holland & Holden, 2016). Moreover, the current findings underscore that emotions, such as anger, maintain a role in concert with cognitive processes, like negative attributions, such that anger regulation training needs to be incorporated more systematically into abuse intervention (e.g., Kolko et al., 2014) and prevention programs (e.g., Sanders et al., 2004). As telehealth approaches have gained traction during the pandemic, parents who are struggling during this period could benefit from mental health professionals directly addressing these socio-emotional elements. With levels of anger and frustration reportedly higher during COVID-19 pandemic (American Psychological Association, 2020), the current findings across outcome measures suggest more emotion-focused interventions to enhance anger regulation are needed in conjunction with cognitive processing when working with parents who continue to have to adjust and balance the evolving pandemic and its consequences.

The following is the supplementary data related to this article.

Standardized coefficients for AAPI-2, CTSPC combined assault, and COVID-19 perceived change in parenting using anger justification.

Footnotes

We thank our participating families and participating Obstetrics/Gynecology clinics that facilitated recruitment. This research was supported by award number R15HD071431 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development or the National Institutes of Health.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- Afifi T.O., Mota N., Sareen J., MacMillan H.L. The relationships between harsh physical punishment and child maltreatment in childhood and intimate partner violence in adulthood. BMC Public Health. 2017;17:493–593. doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4359-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association Stress in America 2020: Stress in the time of COVID-19 (volume 3) 2020. https://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/stress/2020/stress-in-america-covid-july.pdf Retrieved from.

- Ateah C.A., Durrant J.E. Maternal use of physical punishment in response to child misbehavior: Implications for child abuse prevention. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2005;29:169–185. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azar S.T., Okado Y., Stevenson M.T., Robinson L.R. A preliminary test of social information processing model of parenting risk in adolescent males at risk for later physical child abuse in adulthood. Child Abuse Review. 2013;22:268–286. doi: 10.1002/car.2244. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bavolek S.J., Keene R.G. Family Development Resources, Inc; 2001. Adult-Adolescent Parenting Inventory (AAPI-2): Administration and development handbook. [Google Scholar]

- Berlin L.J., Dodge K.A., Reznick J.S. Examining pregnant women’s hostile attributions about infants as a predictor of offspring maltreatment. JAMA Pediatrics. 2013;167:549–553. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.1212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borrajo E., Gámez-Guadiz M., Calvete E. Justification beliefs of violence, myths about love and cyber dating abuse. Psicothema. 2015;27:327–333. doi: 10.7334/psicothema2015.5.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown S.M., Orsi R., Chen P.C.B., Everson C.L., Fluke J. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on child protection system referrals and responses in Colorado, USA. Child Maltreatment. 2021 doi: 10.1177/10775595211012476. Online first. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullinger L.R., Raissian K.M., Feely M., Schneider W. 2020. The neglected ones: Time at home during COVID-19 and child maltreatment. Available at SSRN. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvete E., Orue I. Social information processing as a mediator between cognitive schemas and aggressive behavior in adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2012;40:105–117. doi: 10.1007/s10802-011-9546-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camilo C., Vaz Garrido M., Calheiros M.M. The social information processing model in child physical abuse and neglect: A meta-analytic review. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2020;108 doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaffin M., Valle L. Dynamic prediction characteristics of the child abuse potential inventory. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2003;27:463–481. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2134(03)00036-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connell C.M., Strambler M.J. Experiences with COVID-19 stressors and parents’ use of neglectful, harsh, and positive parenting practices in the northeastern United States. Child Maltreatment. 2021;26:255–266. doi: 10.1177/10775595211006465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick N.R., Dodge K.A. A review and reformulation of social information-processing mechanisms in children’s social adjustment. Psychological Bulletin. 1994;115:74–101. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.115.1.74. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Durrant J.E., Trocmé N., Fallon B., Milne C., Black T. Protection of children from physical maltreatment in Canada: An evaluation of the supreme Court’s definition. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment, & Trauma. 2009;18:64–87. doi: 10.1080/10926770802610640. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz-Aguado M.J., Martinez R. Types of adolescent male dating violence against women, self-esteem, and justification of dominance and aggression. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2015;30:2636–2658. doi: 10.1177/0886260514553631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durrant J.E., Plateau D.P., Ateah C., Stewart-Tufescu A., Jones A., Tapanya S.… Preventing punitive violence: Preliminary data on the positive discipline in everyday parenting (PDEP) program. Canadian Journal of Community Mental Health. 2014;33:109–125. doi: 10.7870/cjcmh-2014-018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gassman-Pines A., Gennetian L.A. Society for Research in Child Development; 2020. COVID-19 job and income loss jeopardize child well-being: Income support policies can help.https://www.srcd.org/sites/default/files/resources/FINAL_SRCDCEB-JobLoss.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Gershoff E.T. More harm than good: A summary of the scientific research on the intended and unintended effects of corporal punishment on children. Law and Contemporary Problems. 2010;73:31–56. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25766386 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gershoff E.E., Grogan-Kaylor A. Spanking and child outcomes: Old controversies and new meta-analyses. Journal of Family Psychology. 2016;30:453–469. doi: 10.1037/fam0000191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gershoff E.T., Lee S.J. American Psychological Association; 2020. Ending the physical punishment of children: A guide for clinicians and practitioners. [Google Scholar]

- Haskett M.E., Scott S.S., Willoughby M., Ahern L., Nears K. The parent opinion questionnaire and child vignettes for use with abusive parents: Assessment of psychometric properties. Journal of Family Violence. 2006;21:137–151. doi: 10.1007/s10896-005-9010-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hien D., Cohen L.R., Caldeira N.A., Flom P., Wasserman G. Depression and anger as risk factors underlying the relationship between substance involvement and child abuse potential. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2010;34:105–111. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiraoka R, Crouch J.L., Reo G, Wagner M.F., Milner J.S., Skowronski J.J. Borderline personality features and emotion regulation deficits are associated with child physical abuse potential. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2016;52:177–184. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holden G.W. In: Abstracts: Vol. 2. Handbook of family measurement techniques. Touliatos B.J., Perlmutter R., Holden G.W., editors. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2001. Attitude toward spanking (ATS) p. 209. [Google Scholar]

- Holland G.W., Holden G.W. Changing orientations to corporal punishment: A randomized, control trial of the efficacy of a motivational approach to psycho-education. Psychology of Violence. 2016;6(2):233–242. doi: 10.1037/a0039606. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Humphreys K.L., Myint M.T., Zeanah C.H. Increased risk for family violence during the COVID-19 pandemic. Pediatrics. 2020;146 doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-0982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley M.L., Power T.G., Wimbush D.D. Determinants of disciplinary practices in low-income black mothers. Child Development. 1992;63:573–582. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1992.tb01647.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr M.L., Rasmussen H.F., Fanning K.A., Braaten S.M. Parenting during COVID-19: A study of parents' experiences across gender and income levels. Family Relations. 2021 doi: 10.1111/fare.12571. Online First. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K., Mennen F.E., Trickett P.K. Patterns and correlates of co-occurrence among multiple types of child maltreatment. Child & Family Social Work. 2017;22:492–502. doi: 10.1111/cfs.12268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King A.R., Ratzak A., Ballantyne S., Knutson S., Russell T.D., Pogalz C.R., Breen C.M. Differentiating corporal punishment from physical abuse in the prediction of lifetime aggression. Aggressive Behavior. 2018;44:306–315. doi: 10.1002/ab.21753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolko D.J., Simonich H., Loiterstein A. In: Evidence-based approaches for treatment of maltreated children. Timmer S., Urquiza A., editors. Springer; 2014. Alternative for families: A cognitive behavioral therapy: An overview and case example. [Google Scholar]

- Lansford J.E., Woodlief D., Malone P.S., Oburu P., Pastorelli C., Skinner A.T., Dodge K.A.… A longitudinal examination of mothers’ and fathers’ social information processing biases and harsh discipline in nine countries. Development and Psychopathology. 2014;26:561–573. doi: 10.1017/S0954579414000236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson M., Piel M.H., Simon M. Child maltreatment during the COVID-19 pandemic: Consequences of parental job loss on psychological and physical abuse towards children. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2020;110 doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S.J., Ward K.P., Chang O.D., Downing K. Parenting activities and the transition to home-based education during the COVID-19 pandemic. Child & Youth Services Review. 2021;122 doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S.J., Ward K.P., Lee J.Y., Rodriguez C.M. Parental social isolation and child maltreatment risk during a pandemic. Journal of Family Violence. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s10896-020-00244-3. Online First. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemerise E.A., Arsenio W.F. An integrated model of emotion process and cognition in social information processing. Child Development. 2000;71:107–118. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy R.J., Crouch J.L., Basham A.R., Milner J.S., Skowronski J.J. Validating the voodoo doll task as a proxy for aggressive parenting behavior. Psychology of Violence. 2016;6:135–144. doi: 10.1037/a0038456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milner J.S. In: Nebraska symposium on motivation, Vo. 46, 1998: Motivation and child maltreatment. Hansen D.J., editor. University of Nebraska Press; Lincoln: 2000. Social information processing and child physical abuse: Theory and research; pp. 39–84. Online first. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musser E.D., Riopelle C., Latham R. Child maltreatment in the time of COVID-19: Changes in the Florida foster care system surrounding the COVID-19 safer-at-home order. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2021;116 doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2021.104945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palan S., Schitter C. Prolific.ac–A subject pool for online experiments. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance. 2018;17:22–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jbef.2017.12.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick S.W., Henkhaus L.E., Zickafoose J.S., Lovell K., Halvorson A., Loch S., Mia L., Davis M.M. Well-being of parents and children during the COVID-19 pandemic: A national survey. Pediatrics. 2020;146 doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-016824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plotkin R. University of Rochester; 1983. Cognitive mediation in disciplinary actions among mothers who have abused or neglected their children: Dispositional and environmental factors. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- Prinz R., Sanders M., Shapiro C., Whitaker D., Lutzker J. Population-based prevention of child maltreatment: The U.S. Triple P system population trial. Prevention Science. 2009;10:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s11121-009-0123-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapoport E., Reisert H., Schoeman E., Adesman A. Reporting of child maltreatment during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic in New York City from march to may 2020. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2021;116 doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez C.M. Predicting parent-child aggression risk: Cognitive factors and their interaction with anger. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2018;33:359–378. doi: 10.1177/0886260516629386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez C.M. In: Shackelford T.K., editor. Vol 1. SAGE Publishing; 2021. Mothers’ non-lethal physical abuse of children; pp. 448–470. (The SAGE handbook of domestic violence). [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez C.M., Baker L.R., Pu D.F., Tucker M.C. Predicting parent-child aggression risk in mothers and fathers: Role of emotion regulation and frustration tolerance. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2017;26 doi: 10.1007/s10826-017-0764-y. 2629-2538. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez C.M., Bower-Russa M., Harmon N. Assessing abuse risk beyond self-report: Analog task of acceptability of parent-child aggression. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2011;35:199–209. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2010.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez C.M., Cook A.E., Jedrziewski C.T. Reading between the lines: Implicit assessment of the association of parental attributions and empathy with abuse risk. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2012;36:564–571. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2012.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez C.M., Lee S.J. Role of maternal emotion in child maltreatment risk during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Family Violence. 2022 doi: 10.1007/s10896-022-00379-5. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez C.M., Lee S.J., Ward K.P. Underlying mechanisms for racial disparities in parent-child physical and psychological aggression and child abuse risk. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2021;17 doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2021.105089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez C.M., Lee S.J., Ward K.P., Pu D.F. The perfect storm: Hidden risk of child maltreatment during the COVID-19 pandemic. Child Maltreatment. 2021;26:139–151. doi: 10.1177/1077559520982066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez C.M., Pu D.F. In: Handbook of interpersonal violence across the lifespan. Geffner R., Vieth V., Vaughan-Eden V., Rosenbaum A., White J., editors. Springer; 2020. Parents who physically abuse: Current status and future directions; pp. 1–22. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez C.M., Richardson M.J. Stress and anger as contextual factors and preexisting cognitive schemas: Predicting parental child maltreatment risk. Child Maltreatment. 2007;12:325–337. doi: 10.1007/s10578-007-0077-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez C.M., Silvia P.J., Gaskin R.E. Predicting maternal and paternal parent-child aggression risk: Longitudinal multimethod investigation using social information processing theory. Psychology of Violence. 2019;9:370–382. doi: 10.1037/vio0000115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez C.M., Silvia P.J., Lee S.J., Grogan-Kaylor A. Assessing mothers’ automatic affective and discipline reactions to child behavior in relation to child abuse risk: A dual-processing investigation. Assessment. 2022;29:1532–1547. doi: 10.1177/10731911211020114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez C.M., Smith T.L., Silvia P.J. Parent-child aggression risk in expectant mothers and fathers: A multimethod theoretical approach. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2016;25:3220–3235. doi: 10.1007/s10826-016-0481-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez C.M., Wittig S.M.O., Christl M. Psychometric evaluation of a brief assessment of parents’ disciplinary alternatives. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2019;28:1490–1501. doi: 10.1007/s10826-019-01387-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez C.M., Wittig S.M.O., Silvia P.J. Refining social-information processing theory: Predicting maternal and paternal parent-child aggression risk longitudinally. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2020;107 doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders M.R., Pidgeon A.M., Gravestock F., Connors M.D., Brown S., Young R.W. Does parental attributional retraining and anger management enhance the effects of the triple-P positive parenting program with parents at risk for child maltreatment. Behavior Therapy. 2004;35:513–535. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7894(04)80030-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sari N.P., van IJzendoorn M.H., Jansen P., Bakermans-Kranenburg M., Riem M.M.E. Higher levels of harsh parenting during the COVID-19 lockdown in the Netherlands. Child Maltreatment. 2021 doi: 10.1177/10775595211024748. Online First. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedlak A.J., Mettenburg J., Basena M., Petta I., McPherson K., Greene A., Li S. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Washington, DC: 2010. Fourth National Incidence Study of child abuse and neglect (NIS–4): Report to congress, executive summary.www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/opre/nis4_report_congress_full_pdf_jan2010.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Sinko L., He Y., Kishton R., Ortiz R., Jacobs L., Fingerman M. “The stay at home order is causing things to get heated up”: Family conflict dynamics during COVID-19 from the perspectives of youth calling a national child abuse hotline. Journal of Family Violence. 2021:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s10896-021-00290-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smeijers D., Benbouriche M., Garofalo C. The association between emotion, social information processing, and aggressive behavior: A systematic review. European Psychologist. 2020;25(2):81–91. doi: 10.1027/1016-9040/a000395. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith Slep A.M., O’Leary S.G. Multivariate models of mothers’ and fathers’ aggression toward their children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:739–751. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.5.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sneed R.S., Kent K., Bailey S., Johnson-Lawrence V. Social and psychological consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic in African-American communities: Lessons from Michigan. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2020;12:446–448. doi: 10.1037/tra0000881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger C.D. Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc; 1988. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAXI) [Google Scholar]

- Spinazzola J., Hodgdon H., Liange L., Ford J.D., Layne C.M., Pynoos R., Kisiel C.… Unseen wounds: The contribution of psychological maltreatment to child and adolescent mental health and risk outcomes. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2014;6:S18–S28. doi: 10.1037/a0037766. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stith S.M., Liu T., Davies C., Boykin E.L., Alder M.C., Harris J.M., Dees J.E.M.E.G.… Risk factors in child maltreatment: A meta-analytic review of the literature. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2009;14:13–29. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2006.03.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Straus M.A. Corporal punishment and primary prevention of physical abuse. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2000;24:1109–1114. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2134(00)00180-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus M.A. New evidence for the benefits of never spanking. Society. 2001;38:52–60. doi: 10.1007/BF02712591. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Straus M.A., Hamby S.L., Finkelhor D., Moore D.W., Runyan D. Identification of child maltreatment with the parent-child conflict tactics scales: Development and psychometric data for a national sample of american parents. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1998;22:249–270. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2134(97)00174-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoltenborgh M., Bakermans-Kranenburg M.J., Alink L.R.A., van IJzendoorn M.H. The prevalence of child maltreatment across the globe: Review of a series of meta-analyses. Child Abuse Review. 2015;24:37–50. doi: 10.1002/car.2353. Retrieved from. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Twenge J.M., Joiner T.E. U.S. Census Bureau-assessed prevalence of anxiety and depressive symptoms in 2019 and during the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic. Depression & Anxiety. 2021;37:954–956. doi: 10.1002/da.23077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Department of Health and Human Services Child maltreatment 2020. 2022. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/cb/report/child-maltreatment-2020 Retrieved from.

- Whelan J., Hartwell M., Chesher T., Coffey S., Hendrix A.D., Passmore S.J.…Greiner B. Deviations in criminal filings of child abuse and neglect during COVID-19 from forecasted models: An analysis of the state of Oklahoma, USA. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2021;116 doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiggins B.J., Christopherson C.D. The replication crisis in psychology: An overview for theoretical and philosophical psychology. Journal of Theoretical and Philosophical Psychology. 2019;39(4):202–217. doi: 10.1037/teo0000137. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Standardized coefficients for AAPI-2, CTSPC combined assault, and COVID-19 perceived change in parenting using anger justification.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.