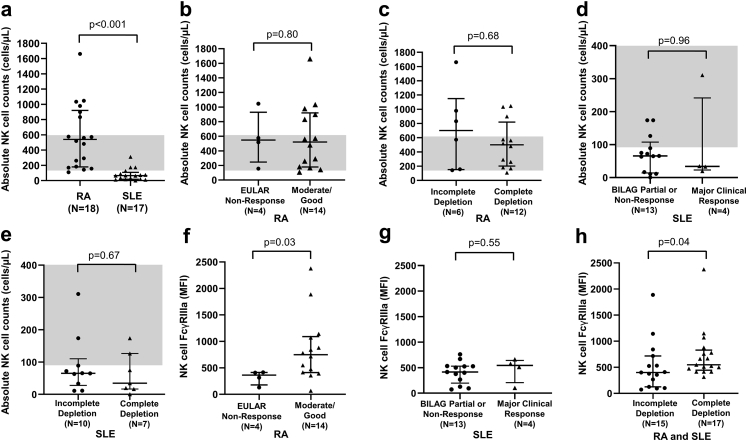

Fig. 5.

Peripheral blood NK-cell abundance and FcγRIIIa expression in rituximab-treated RA and SLE patients. Comparison of absolute natural killer (NK)-cell (CD3-CD56+) counts between (a) rituximab-treated rheumatoid arthritis (RA) (n = 18) and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) (n = 17) patients; (b) rituximab-treated RA patients exhibiting no European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) clinical response (n = 4) and moderate/good clinical response (n = 14); (c) rituximab-treated RA patients exhibiting incomplete (n = 6) and complete B-cell depletion (n = 12); (d) rituximab-treated SLE patients exhibiting British Isles Lupus Assessment Group (BILAG) partial clinical response or no clinical response (n = 13) and major clinical response (n = 4); and (e) rituximab-treated SLE patients with incomplete (n = 10) and complete B-cell depletion (n = 7). The shaded grey areas represent adult reference ranges of the absolute NK-cell counts (90–600 cells/μL). Expression of FcγRIIIa (CD16; clone 3G8) on NK-cells of (f) RA patients exhibiting EULAR non-response (n = 4) and moderate/good clinical response (n = 14) to rituximab; (g) SLE patients exhibiting BILAG partial clinical response/non-response (n = 13) and major clinical response (n = 4) to rituximab; and (h) RA and SLE patients exhibiting incomplete (n = 15) and complete B-cell depletion (n = 17) in response to rituximab. All p-values calculated using non-parametric Mann–Whitney test. Data were summarised as median and the error bars denoted interquartile range.