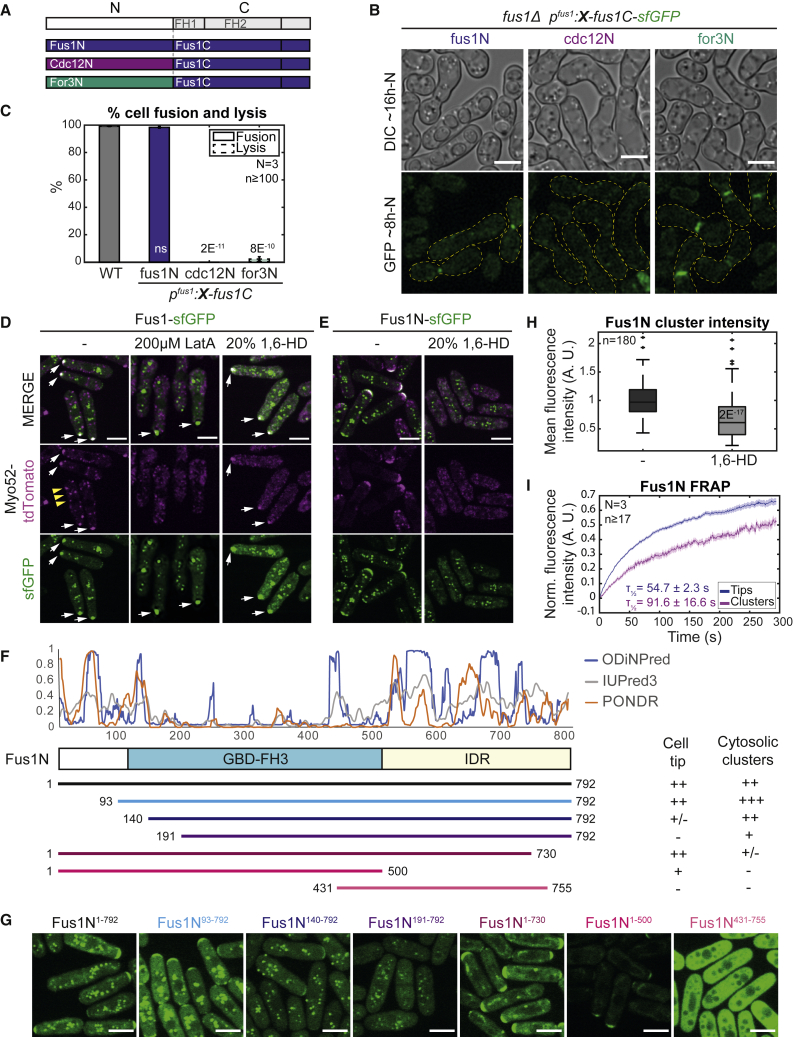

Figure 1.

Fus1N is essential for fusion and has localization and self-association properties

(A) Formin chimeras tagged C-terminally with sfGFP.

(B) DIC and GFP images ∼16 and ∼8 h post starvation of fus1Δ cells expressing the chimeric formins shown in (A). Yellow dashed lines outline mating pairs.

(C) Percentage of cell pair fusion and lysis 24 h post starvation in WT and strains as in (B). p values relative to WT.

(D) Interphase cells expressing Myo52-tdTomato and full-length Fus1-sfGFP from the nmt1 promotor. Cells were either untreated (left), treated with 200 μM latrunculin A (middle), or with 20% 1,6-hexanediol (right) for 5 min. White arrows mark resistant fusion focus-like structure; yellow arrowheads indicate labile Myo52 dots.

(E) Interphase cells expressing Myo52-tdTomato and Fus1N-sfGFP (Fus11–792) from the nmt1 promoter. Cells were either untreated (left) or treated with 20% 1,6-hexanediol for 5 min (right).

(F) Scheme of Fus1N with predicted domain organization. The top graph shows the disorder index of 3 prediction tools.12,13,14 Fragments were C-terminally tagged with sfGFP. The localization summary is shown on the right.

(G) GFP-fluorescence images of constructs as in (F).

(H) Boxplot of Fus1 clusters mean fluorescence intensity of cells as in (E). The p value relative to untreated condition.

(I) Average Fus1N FRAP recovery curves normalized to pre-bleach values in cells as in (E). The mean recovery half-time and standard deviation are indicated. N = 3 independent experiments, with n > 17 cells each (n > 54 cells in total). The shaded area shows the standard error. Scale bars, 5 μm.

See also Figure S1.