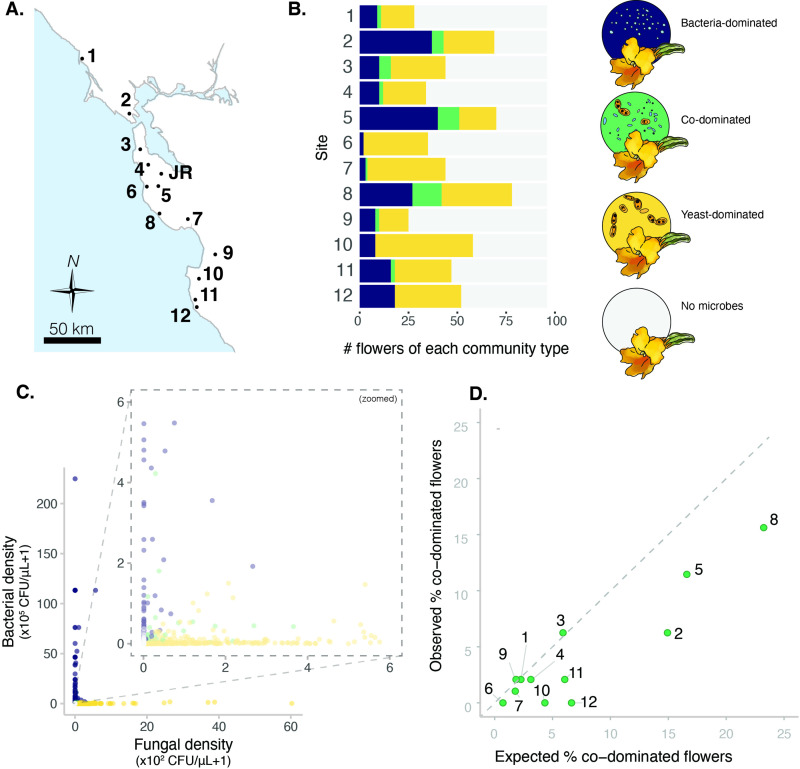

Figure 2. Sites vary in regional dominance of bacteria and yeast.

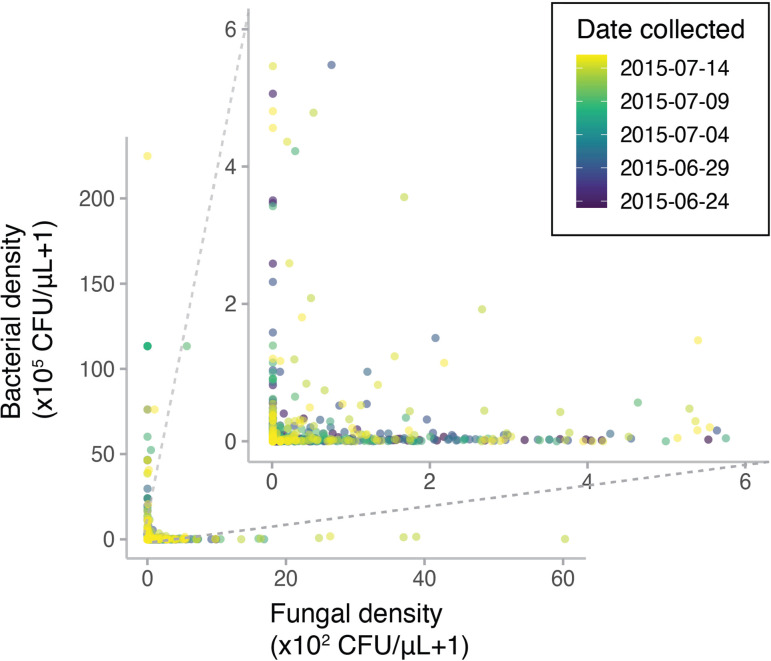

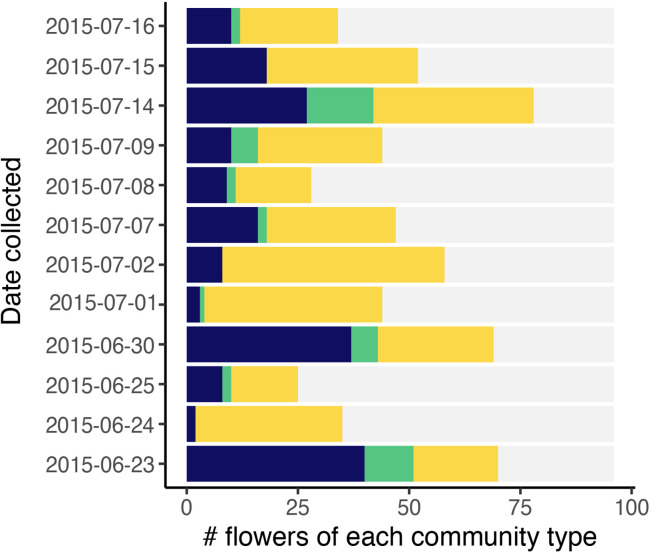

(A) Ninety-six Diplacus aurantiacus flowers were harvested from each of 12 field sites in and around the San Francisco Peninsula in California, USA (Figure 2—source data 1) with (B) variable numbers of flowers classified as bacteria-dominated (blue), fungi-dominated (yellow), co-dominated (green) flowers, or flowers where microbes were too rare to determine (grey) (n=1152). (C) Flowers are often dominated by bacteria or yeast, but rarely both. Each point represents a floral community and inset plot represents zoomed-in version of the plot behind it (n=1152). (D) Co-dominated flowers were observed less frequently than expected. In panel D, each point represents a site, with the numbers indicating the site numbers shown in panels A and B. In panel A, the location of Jasper Ridge Biological Preserve (JR) is also indicated (n=12).

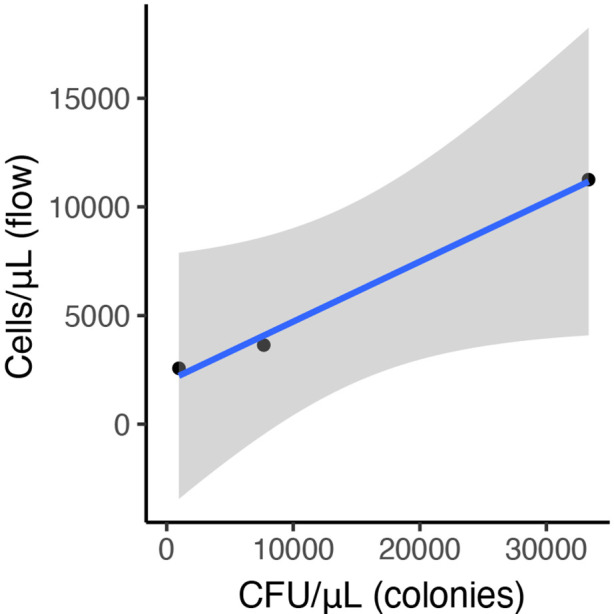

Figure 2—figure supplement 1. Preliminary association between flow cytometry cell counts (populations identified by forward and side scatter) and colony forming units of A. nectaris growing on tryptic soy agar with cycloheximide.