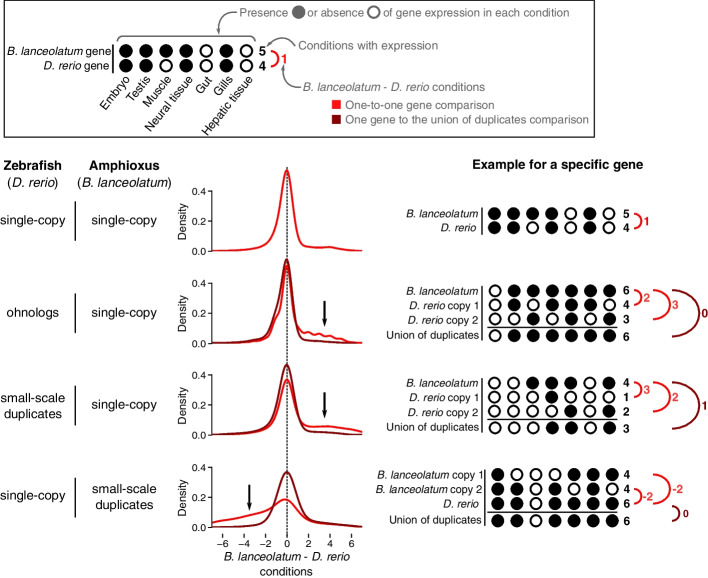

Fig. 5.

Specialization of duplicated genes in amphioxus and zebrafish. Amphioxus average gene expression in embryonic stages, male gonads, muscle, neural tube, gut, gills, and hepatic diverticulum was matched to zebrafish gene expression in embryo, testis, muscle tissue, brain, intestine, pharyngeal gill, and liver, respectively. The presence or absence of gene expression in each condition (either adult tissue or developmental stage whole body) and each species was determined, and the difference in number of expressed conditions between the two species was calculated (B. lanceolatum–D. rerio conditions) for every pair of orthologous genes (one-to-one gene comparison, in red). In the case of duplicated genes, the union of both duplicates’ expression was calculated as the number of conditions in which either of the duplicates is expressed (see examples in figure). The union of duplicates was then compared to their ortholog(s) gene expression in the other species (comparing one single gene to the union of duplicates, in brown). The density of the distribution of this difference in expression between B. lanceolatum and D. rerio is shown for four different types of orthologous genes: genes that are single-copy in both species (first row); zebrafish ohnolog genes that are orthologs to B. lanceolatum single-copy genes (second row); zebrafish small-scale duplicates that are orthologs to single-copy B. lanceolatum genes (third row); and zebrafish single-copy genes that are orthologs to small-scale duplicates B. lanceolatum genes (fourth row). Black arrows highlight the direction of the skewness (when present) of the one-to-one gene comparisons (red lines). Hypothetical examples of each case are schematically shown on the right in order to make the figure clearer