Abstract

Objectives

Firefighters are regularly exposed to potentially traumatic and injurious events and are at increased risk for developing posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms, pain, and pain-related disability. Mindfulness (i.e., present-oriented awareness and nonjudgmental acceptance of cognitions and bodily sensations) may influence PTSD-pain relations in firefighter populations and inform mutual maintenance models. The current cross-sectional study sought to examine the moderating role of mindfulness on the associations between PTSD symptom severity and pain-related disability and intensity among trauma-exposed firefighters.

Methods

Firefighters (N = 266; Mage = 40.48, SD = 9.70; 92.5% male) were recruited from a large, southwestern metropolitan area and voluntarily completed an online, self-report survey advertised throughout the fire department.

Results

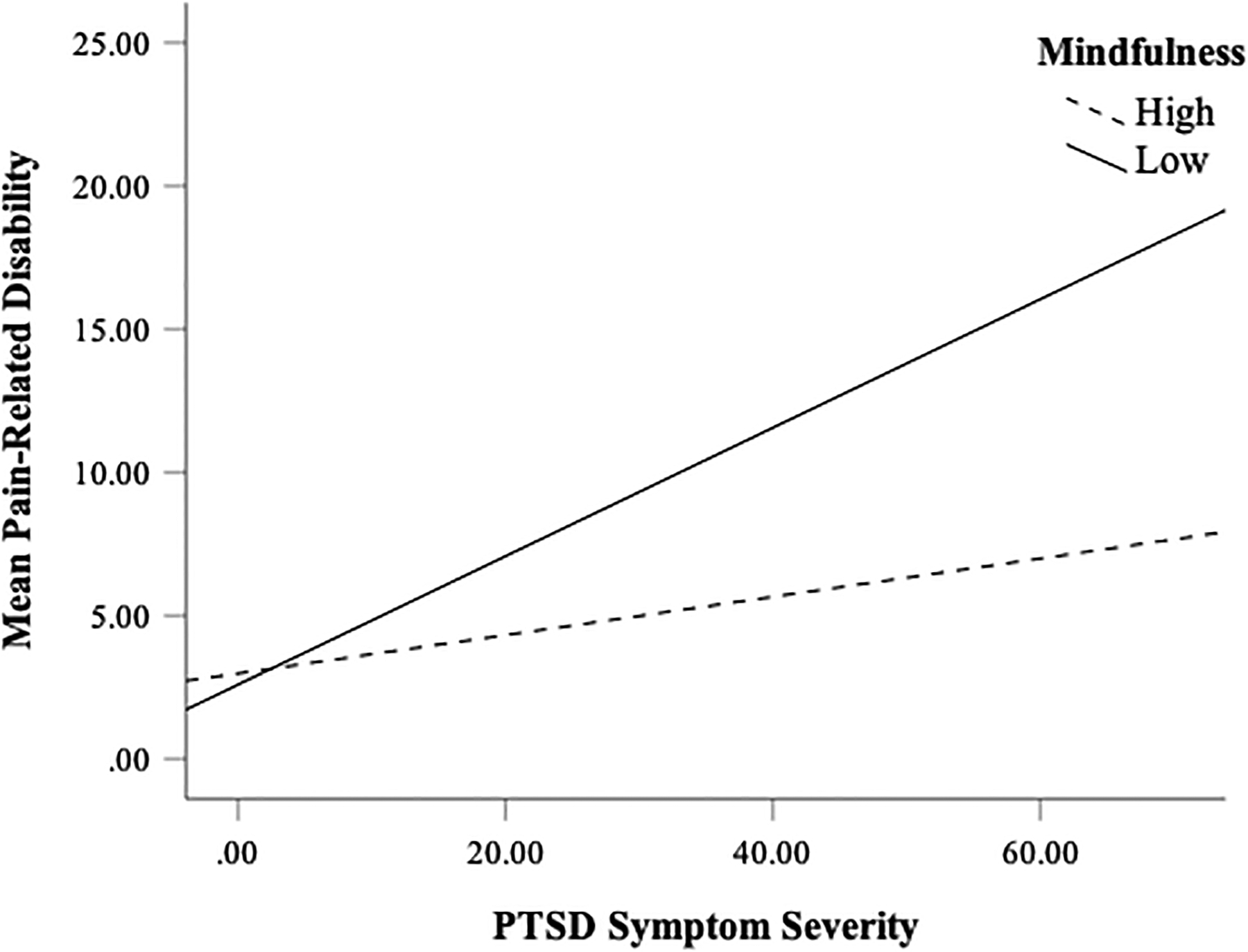

Accounting for covariates (i.e., age, years in the fire service, trauma load), a significant interactive effect of PTSD symptom severity and mindfulness on pain-related disability (ΔR2 = 0.05, B = − 0.16, p < .001), but not pain intensity, emerged. Simple slope analyses revealed that PTSD symptom severity was associated with pain-related disability for those with low, but not high mindfulness. Post hoc analyses examining mindfulness facets revealed significant main effects of acting with awareness, non-judging of inner experience, and nonreactivity to inner experience on pain-related disability. Significant interactive effects of observing, describing, and nonreactivity to inner experience with PTSD symptom severity on pain-related disability emerged.

Conclusions

Mindfulness moderates PTSD symptom severity and pain-related disability associations in trauma-exposed firefighters. Future work should further examine these associations among first responders, using experimental and/or longitudinal methodologies.

Keywords: Trauma, PTSD, Mindfulness, Pain, Disability, Firefighters, First responders

Firefighters are frequently exposed to potentially traumatic events (Jahnke et al., 2016; Lee et al., 2017) and experience disproportionally higher occupational injury and fatality rates compared to other working populations (Bos et al., 2004; Nazari et al., 2020a, b). Indeed, the public health burden and economic costs associated with job-related pain and disability in firefighters are substantial, with annual costs exceeding $900 million in the United States (U.S.; Jahnke et al., 2013). Recurrent injury, long shift work, heavy work-related equipment, physically demanding tasks, and exposure to physical danger predispose firefighters to greater incidences of acute pain (e.g., sprains) and long-term, chronic disability (e.g., low back pain; Nazari et al., 2020a, b; Soteriades et al., 2019). Extant work has found that the vast majority of firefighters experience intense and severe job-related pain, including musculoskeletal pain, lower back pain, sprains, and strains (Kim et al., 2017; Nazari et al., 2020a, b). As a result, firefighters often experience work limitations (i.e., health challenges that interfere with various aspects of job performance), which impact daily occupational and personal functioning and career longevity (Gallagher, 2005; Negm et al., 2017). Given the high prevalence of injury and pain among firefighters, it is important to explore pertinent factors that may relate to pain intensity and pain-related disability.

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) provides a clinically relevant avenue for understanding pain intensity and pain-related disability among firefighters (Asmundson et al., 2002). Given high rates of exposure to potentially traumatic events (Meyer et al., 2012; Skeffington et al., 2017), firefighters are at increased risk of developing PTSD and subclinical PTSD (i.e., symptoms that do not meet the categorical diagnostic threshold; Tomaka et al., 2017). Prevalence rates for PTSD among firefighters in the U.S. are estimated to be more than three times greater than those found in the general population (8.3%; Kilpatrick et al., 2013; 32.4%; Tomaka et al., 2017). PTSD and subclinical PTSD are uniquely associated with acute pain, chronic pain, and pain-related disability (Outcalt et al., 2015; Siqveland et al., 2017) and the mutual maintenance model posits that PTSD symptomatology and pain evince bidirectional, temporal relationships (McAndrew et al., 2019). Indeed, a recent meta-analysis found that military veterans with PTSD, compared to those without PTSD, evinced greater levels of pain, disability, and healthcare utilization and lower pain self-efficacy (i.e., perceived confidence to cope with pain; Benedict et al., 2020). Available work among firefighters has found higher rates of work-related injury, chronic musculoskeletal disorder (e.g., low back pain), and chronic pain in firefighters with PTSD, compared to those without PTSD (Carleton et al., 2018; Katsavouni et al., 2016). Given the public health and economic costs associated with pain and disability as well as PTSD symptomatology, identifying and evaluating malleable cognitive-affective factors that may contribute to the attenuation and management of pain among firefighters with PTSD symptomatology provides a clinically significant target for improving mental and physical health outcomes as well as occupational functioning in this vulnerable population.

Mindfulness, broadly defined as purposeful focus to and awareness of the present moment and the nonreactive and non-judgmental acceptance of adverse emotional states (Baer et al., 2006), offers a relevant cognitive-affective factor associated with both pain and PTSD symptomatology. Trait mindfulness is defined as the innate capacity to engage in mindfulness, generally (e.g., mindfulness in daily life), as opposed to state mindfulness, defined as the ability to engage in mindfulness in a specific moment or context (e.g., mindfulness during meditation; Bravo et al., 2018). As measured by the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ; Baer et al., 2006), trait mindfulness is composed of five facets: observing, describing, acting with awareness, non-judging of inner experience, and nonreactivity to inner experience. Strong negative associations between trait mindfulness and acute and chronic pain have been documented across populations (McClintock et al., 2019), such that heightened levels of trait mindfulness are associated with lower pain levels and vice versa. Furthermore, mindfulness-based interventions (including randomized controlled trials [RCTs]) have emerged as an effective, nonpharmacological avenue for pain management across various ailments and populations (Andersen & Vaegter, 2016; Hilton et al., 2017), demonstrating comparable benefits and reduced risk of side-effects to more traditional pharmacotherapy approaches (e.g., opioid therapy; McClintock et al., 2019). Similarly, mindfulness is negatively associated with PTSD symptom severity (Hopwood & Schutte, 2017; Lebeaut et al., 2020; Polusny et al., 2015), particularly with PTSD intrusion (e.g., flashbacks, unwanted upsetting memories) and negative alterations in cognitions and mood symptom clusters (e.g., negative affect, self-directed blame and guilt; Reffi et al., 2019). In addition, mindfulness-based interventions offer a clinically meaningful approach to PTSD symptom reduction, indicating moderate to large effect sizes across numerous RCTs (Niles et al., 2018).

While the literature is considerably limited, two RCTs have explicitly and concurrently examined the efficacy of mindfulness-based interventions on pain and PTSD outcomes. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis found promising outcomes among mindfulness-based interventions for the treatment of comorbid PTSD and pain and/or disability (Goldstein et al., 2019). For example, in a RCT of 55 military veterans, those veterans randomized to the Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) program reported greater reductions in pain, depressive symptoms, and PTSD symptoms, as compared to the treatment-as-usual only group (Kearney et al., 2016). Another RCT among post-9/11 veterans and their partners (i.e., veteran-partner dyads; N = 160), who completed a mindfulness-based Mission Reconnect (MR) program, demonstrated positive outcomes (n = 45; Kahn et al., 2016). Specifically, veterans randomized to the single session, MR-program-only treatment arm evinced greater reductions in PTSD symptoms and average weekly pain levels at follow-up, relative to those in the waitlist control contrition (n = 48; Kahn et al., 2016).

Theoretically, firefighters who are repeatedly exposed to traumatic events and develop PTSD symptomatology may be predisposed to also develop pain-inducing ailments and disability resulting from both trauma exposure and physically demanding work-related duties (e.g., Asmundson & Hadjistavropolous, 2006; Nazari et al., 2020a, b). In turn, it might be expected that firefighters with increased PTSD symptomatology experience greater pain-related intensity and disability over time, given established PTSD-pain relations (e.g., Siqveland et al., 2017). Indeed, heightened PTSD symptomatology has been shown to influence changes in neuroanatomical structure and neurobiological processes (e.g., increased amygdala plasticity; Mahan & Ressler, 2012; Rauch et al., 2006), increase sensitivity to threat (via PTSD-related hypervigilance), and amplification of subjective pain experience (i.e., attention to pain and pain catastrophizing; Lewis et al., 2012; Sharp & Harvey, 2001). Mindfulness, broadly, and specific mindfulness facets (i.e., acting with awareness, non-judging of inner experience, and nonreactivity to inner experience), are negatively associated with PTSD symptomatology (e.g., Martin et al., 2018; Stanley et al., 2019) and may help regulate PTSD-related affective states and experiential avoidance (e.g., Reffi et al., 2019). For example, improving mindfulness may elicit more adaptive cognitions and affective responses (i.e., improved emotion regulation and pain management) for trauma-exposed firefighters with PTSD symptoms (e.g., Hopwood & Schutte, 2017) and acute/chronic pain and disability (e.g., McClintock et al., 2019) and enhance strategies to cope with the negative emotional states and experiences associated with PTSD and pain. Therefore, it may follow that lower levels of mindfulness (e.g., a reduced ability to remain nonreactive and non-judgmental to adverse emotional states) may exacerbate (i.e., moderate) the established association between PTSD symptoms and pain and/or pain-related disability.

Despite the potentially meaningful role of mindfulness in PTSD-pain associations, there is a relative paucity of work examining these factors concurrently. While various mindfulness-based interventions have targeted concurrent PTSD and pain symptoms (e.g., Kahn et al., 2016; Kearney et al., 2016), few studies have examined associations between PTSD and mindfulness with regard to pain and pain-related disability (cf., Dahm et al., 2015; Meyer et al., 2018). Moreover, no published studies have explored these relations in firefighters. This is unfortunate given the emerging literature investigating the efficacy of mindfulness-based interventions in first responders (e.g., Canady et al., 2021; Denkova et al., 2020; Joyce et al., 2018).

Therefore, the current study aimed to examine the main and interactive effects of PTSD symptom severity and mindfulness with pain intensity and pain-related disability in firefighters. First, we hypothesized that firefighters with heightened PTSD symptom severity would endorse greater levels of pain intensity and pain-related disability. Second, we hypothesized that firefighters with lower levels of mindfulness would endorse greater levels of pain intensity and pain-related disability. Finally, it was hypothesized that lower levels of mindfulness would exacerbate (i.e., moderate) the associations between PTSD symptom severity and pain intensity and pain-related disability. Additional analyses were conducted to examine the main and interactive effects of each of the five mindfulness facets (i.e., observing, describing, acting with awareness, non-judging of inner experience, and nonreactivity to inner experience) with PTSD as relevant to pain intensity and pain-related disability.

Method

Participants

This study was a secondary analysis of data from a larger project examining stress, resilience, and overall well-being among firefighters (Leonard & Vujanovic, 2021). The sample included 266 firefighters (92.5% male, Mage = 40.48, SD = 9.70) recruited online from career, combination (i.e., volunteer and career), and volunteer fire departments in a large metropolitan area in the southern U.S. Please see Table 1 for a summary of participant characteristics. Participants were composed of full-or part-time career or volunteer firefighters, who perform emergency medical services (EMS) and/or fire suppression services. To be considered eligible for the parent study, participants must have been active firefighters over the age of 18 who provided consent to participate. Exclusionary criteria consisted of an inability or unwillingness to provide consent. To be included in this secondary analysis, participants must have endorsed at least one PTSD Criterion A traumatic life event (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Table 1.

Participant sociodemographic characteristics

| Variables | Mean/n (SD/%) |

|---|---|

| Age | 40.48 (9.70) |

| Years in the fire service | 15.31 (9.08) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 246 (92.5) |

| Female | 19 (7.1) |

| Transgender | 1 (0.4) |

| Race | |

| American Indian or Alaskan Native | 11 (4.1) |

| Asian | 6 (2.3) |

| Black or African American | 14 (5.3) |

| Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander | 1 (0.4) |

| White | 214 (80.5) |

| Other | 20 (7.5) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic or Latino | 50 (18.8) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 216 (81.2) |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 192 (72.2) |

| Living with partner | 15 (5.6) |

| Single | 44 (16.5) |

| Divorced | 15 (5.6) |

| Education | |

| Partial completion of high school or GED equivalent | 110 (41.4) |

| Partial completion of college | 132 (49.6) |

| College graduate | 24 (9.0) |

| Military veteran status | |

| Active duty in the past, but not now | 45 (16.9) |

| Now on active duty | 2 (0.8) |

| Never on active duty except for initial/basic training | 4 (1.5) |

| Never served in the U.S. Armed Forces | 215 (80.8) |

| Trauma loada | 10.68 (2.52) |

| Probable PTSD diagnosisb | 30 (11.28) |

N = 266; SD, standard deviation. Data derived from the Demographics Questionnaire unless otherwise noted.

Life Events Checklist for DSM-5.

PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 total score ≥ 33

Procedures

All firefighters were recruited for participation in the parent study through career, combination, or volunteer fire departments in a large metropolitan area in the southern U.S. Fire department–wide emails across various departments notified all firefighters of the opportunity to complete an online research survey for a chance to win one of several raffle prizes (e.g., assorted gift cards). Firefighters interested in participating were able to access the informed consent form through the continuing education portal or email link, where they were provided with a description of the survey and the informed consent form, which delineated all aspects of the study. The total amount of time required for participation was estimated to be 30–45 min. Firefighters could discontinue participation at any time without penalty. The study protocol was approved by all relevant institutional review boards and participating fire departments.

Measures

Demographics Questionnaire

Participants were asked to self-report demographic and medical history information including sociodemographic characteristics and firefighter service history. In the present study, participant age and number of years in the fire service were included as covariates.

Life Events Checklist for DSM-5 (LEC-5; Weathers et al., 2013)

The LEC-5 is a self-report questionnaire used to screen for potentially traumatic events experienced at any time throughout the lifespan. Respondents are provided with a list of 16 potentially traumatic events (e.g., combat, sexual assault, transportation accident) as well as an additional item assessing for “other” potentially traumatic events not listed. Respondents are asked to indicate whether each listed event “happened to me”, “witnessed it”, “learned about it”, “part of my job”, or “not sure”. If an event is endorsed as “happened to me”, “witnessed it”, or “part of my job”, then that particular type of event was coded as a positive exposure. The total number of trauma exposure types was summed to produce a “trauma load” variable. In the present study, trauma load (i.e., total number of trauma exposure types) was included as a covariate.

PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5; Blevins et al., 2015)

Respondents were asked to complete the PCL-5 regarding the “worst” traumatic event endorsed on the LEC-5. The PCL-5 is a 20-item self-report questionnaire that measures PTSD symptom severity over the past month. Each of the 20 items reflects a symptom of PTSD according to DSM-5 criteria (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Participants were asked to rate each item on a 5-point scale (0 = Not at all to 4 = Extremely) to indicate how much they were bothered by the symptom in the past month. Total symptom severity scores range from 0 to 80, with higher scores indicating greater severity. A score of 33 or greater is the suggested cut-off for a probable diagnosis of PTSD (Bovin et al., 2016). The measure has demonstrated excellent psychometric properties in previous work (Blevins et al., 2015; Morey, 2007) and the internal consistency and reliability for the PCL-5 total score, a predictor variable, was excellent (α = 0.95; ω = 0.96).

Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ; Baer et al., 2006)

The FFMQ is a 39-item measure that assesses the five facets of mindfulness (Baer et al., 2006). Participants were asked to rate each item using a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = never or very rarely true to 5 = very often or always true), and certain items are reversed scored (e.g., a score of 5 is reversed to a 1). Higher scores on the FFMQ indicate greater mindfulness. The observing subscale measures attention to internal and external experiences (e.g., “When I’m walking, I deliberately notice the sensations of my body moving”); the describing subscale pertains to the ability to label internal experiences (e.g., “I can easily put my beliefs, opinions, and expectations into words”); the acting with awareness subscale assesses for attentiveness to activities in the moment (e.g., “When I do things, my mind wanders off and I’m easily distracted”); the non-judging of inner experience subscale measures the ability to withhold evaluative perceptions about their internal experiences (e.g., “I criticize myself for having irrational or inappropriate emotions”); and the nonreactivity to inner experience subscale measures the ability to manage the persistence of internal experiences (e.g., “I watch my feelings without getting lost in them”; Baer et al., 2006). The FFMQ has exhibited good psychometric properties in past work (Baer et al., 2008) and the internal consistency and reliability of each FFMQ subscale ranged from good to excellent: observing (α = 0.86;ω = 0.86) describing (α = 0.87; ω = 0.85), acting with awareness (α = 0.91; ω = 0.91), nonjudging of inner experience (α = 0.90; ω = 0.90), and nonreactivity to inner experience (α = 0.82; ω = 0.81). In the main analyses, the average total score of the FFMQ (i.e., the average rating by a participant across all items) was used as a predictor and moderator variable. Each of the FFMQ subscale average scores (observing, describing, acting with awareness, non-judging of inner experience, and nonreactivity to inner experience) were examined as moderators in the post hoc exploratory analyses.

Graded Chronic Pain Scale (GCPS; Von Korff et al., 1992)

The GCPS is an 8-item questionnaire used to assess selfperceptions of pain intensity and pain-related disability in the past three months. Respondents were asked to rate the three pain intensity items on an 11-point scale (0 = no pain to 10 = pain as bad as could be), and the four pain disability items on an 11-point scale (0 = no interference to 10 = unable to carry on activities). Total scores range from 0 to 30 and 0 to 40, with higher scores reflecting greater pain intensity and pain-related disability, respectively. The GCPS has demonstrated good psychometric properties across samples with pain and pain-related disability (Raichle et al., 2006; Von Korff et al., 1992) and evinced good to excellent internal consistency and reliability for both the pain intensity (α = 0.86; ω = 0.88) and disability subscales (α = 0.89; ω = 0.90). In the present study, the GCPS pain intensity scale (three items) and disability scale (four items) were used as outcome variables.

Data Analyses

All analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS version 27.0 (IBM Corporation, 2017). First, the database was evaluated for normality and missingness. Data approximated normality and less than 5% of the data were missing and thus handled via listwise deletion. Second, descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations among all study variables were examined. Third, two hierarchical regression analyses were conducted. At step 1, theoretically relevant covariates (i.e., age, years in the fire service, and trauma load [LEC-5 total]) were entered into the model. Covariates were selected given established and distinct associations between pain-related outcomes and age (e.g., reduced pain sensitivity over time; El Tumi et al., 2017) and years in the fire service (e.g., increased probability of work-related injuries, Nazari et al., 2020a, b; Negm et al., 2017) as well as associations between PTSD and trauma load (Harvey et al., 2016). At step 2, mean-centered (to facilitate interpretation) predictor variables of PTSD symptom severity (PCL-5 total score) and mindfulness (FFMQ average score) were entered. At step 3, the interactive effect of PTSD symptom severity by mindfulness was entered. Main and interactive effects were evaluated regarding (1) pain intensity (GCPS Pain Intensity Score) and (2) pain-related disability (GCPS Pain Disability Score). Simple slope analyses were conducted to probe the significant interactions at different levels of the moderator. A Bonferroni correction was applied to control for Type I error across the two hierarchical regression analyses (α = 0.05/2 = 0.025).

Post hoc exploratory hierarchical regression analyses were conducted to follow-up on significant main analyses and examine unique associations between mindfulness facets (FFMQ subscale total average score) and PTSD symptom severity on pain-related outcomes. At step 1, covariates (i.e., age, years in the fire service, and trauma load [LEC-5 total]) were entered into the model. At step 2, mean-centered (to facilitate interpretation) predictor variables of PTSD symptom severity (PCL-5 total score) and each mindfulness facet (FFMQ facet average score) were entered. At step 3, the interactive effect of PTSD symptom severity (PCL-5 total score) by a single mindfulness facet was entered. Accordingly, five hierarchical regressions were conducted to test the interactive effect of each mindfulness facet. A Bonferroni correction was applied to control for Type I error across the five post hoc regression analyses (α = 0.05/5 = 0.01). Simple slope analyses were conducted to probe the significant interactions at different levels of the moderator.

Results

Bivariate Associations Across Study Variables

Bivariate correlations and descriptive statistics are presented in Table 2. PTSD symptom severity was negatively associated with global mindfulness (FFMQ total score) and all mindfulness facets (except observing); and PTSD was positively correlated with pain intensity and pain-related disability. Global mindfulness was negatively correlated with pain intensity and pain-related disability. Regarding covariates, age was negatively correlated with PTSD symptom severity and positively associated with global mindfulness. Years in the fire service was positively correlated with PTSD symptom severity, pain intensity, and pain-related disability. Trauma load was positively correlated with PTSD symptom severity, pain intensity, and pain-related disability. Trauma load was not correlated with global mindfulness.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations of study variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | – | |||||||||||

| 2. Fire servicea | 0.79** | – | ||||||||||

| 3. Trauma loada | 0.12* | 0.16** | – | |||||||||

| 4. PTSD symptomsb | − 0.15* | − 0.08 | 0.21** | – | ||||||||

| 5. Mindfulnessb | 0.14* | 0.05 | − 0.07 | − 0.45** | – | |||||||

| 6. Observinga/b | − 0.08 | − 0.07 | 0.18** | 0.08 | 0.41** | – | ||||||

| 7. Describinga/b | 0.12 | 0.05 | − 0.05 | − 0.36** | 0.80** | 0.26** | – | |||||

| 8. Awarenessa/b | 0.19** | 0.10 | − 0.19** | − 0.41** | 0.58** | − 0.26** | 0.35** | – | ||||

| 9. Nonjudginga/b | 0.16* | 0.09 | − 0.18** | − 0.43** | 0.50** | − 0.35** | 0.25** | 0.59** | – | |||

| 10. Nonreactivitya/b | 0.04 | − 0.03 | 0.06 | − 0.17** | 0.59** | 0.54** | 0.44** | − 0.05 | − 0.12 | – | ||

| 11. Pain intensityc | − 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.24** | 0.36** | − 0.26** | 0.02 | − 0.18** | − 0.23** | − 0.26** | − 0.08 | – | |

| 12. Pain-related disabilityc | − 0.07 | − 0.05 | 0.27** | 0.40** | − 0.33** | 0.02 | − 0.18** | − 0.35** | − 0.30** | − 0.12* | 0.61** | – |

| M | 40.48 | 15.31 | 10.68 | 12.46 | 3.40 | 2.93 | 3.41 | 3.72 | 3.70 | 3.21 | 8.13 | 4.85 |

| SD | 9.70 | 9.08 | 2.52 | 14.56 | 0.49 | 0.91 | 0.87 | 0.84 | 0.88 | 0.81 | 6.14 | 6.71 |

N = 266 trauma-exposed firefighters.

p < 0.01;

p < 0.05.

Covariate.

Predictor.

Outcome.

M, mean; SD, standard deviation; Age, Demographics Questionnaire; Years in the fire service, Demographics Questionnaire; Trauma load, total number of event types endorsed on LEC-5 (Weathers et al., 2013); PTSD symptoms, PCL-5 total score (Blevins et al., 2015); Mindfulness facets (observing, describing, awareness, nonjudging, and nonreactivity), FFMQ subscale total average score (Baer et al., 2006); Pain intensity and pain-related disability reported for the past 3 months, CPGS total subscale scores (Von Korff et al., 1992)

Main and Interactive Effects of Mindfulness and PTSD Symptom Severity

Please see Table 3 and Fig. 1 for a summary of the main analyses. Regarding pain intensity, step 1 contributed 6.7% of variance to the model (p < 0.001), with trauma load emerging as a significant correlate (p < 0.001). Step 2 contributed 10.5% of unique variance (sig. F Δ p < 0.001), and PTSD symptom severity demonstrated a significant main effect (p < 0.001), while mindfulness did not (p < 0.06). In step 3, the interactive effect of PTSD symptom severity by mindfulness was not significantly associated with pain intensity (sig. F Δ p = 0.394).

Table 3.

Main and interactive effects of PTSD symptom severity and mindfulness on pain outcomes

| ΔR 2 | B | SE | t | p | 95% CI | sr 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain intensity | ||||||||

| Step 1 | .067 | |||||||

| Age | − 0.097 | 0.061 | − 1.590 | .113 | − 0.217 | 0.023 | 0.009 | |

| Years in the fire service | 0.085 | 0.065 | 1.301 | .194 | − 0.044 | 0.214 | 0.006 | |

| Trauma load | 0.583 | 0.147 | 3.969 | < .001 | 0.294 | 0.873 | 0.056 | |

| Step 2 | .105 | |||||||

| PTSD symptoms | 0.111 | 0.027 | 4.041 | < .001 | 0.057 | 0.165 | 0.052 | |

| Mindfulness | − 1.522 | 0.790 | − 1.926 | .055 | − 3.077 | 0.034 | 0.012 | |

| Step 3 | .002 | |||||||

| PTSD symptoms × Mindfulness | − 0.034 | 0.039 | − 0.854 | .394 | − 0.111 | 0.044 | 0.002 | |

| Pain-related disability | ||||||||

| Step 1 | .085 | |||||||

| Age | − 0.066 | 0.066 | − 1.003 | .317 | − 0.196 | 0.064 | 0.004 | |

| Years in the fire service | − 0.012 | 0.071 | − 0.168 | .866 | − 0.152 | 0.128 | 0.000 | |

| Trauma load | 0.758 | 0.159 | 4.765 | < .001 | 0.445 | 1.072 | 0.079 | |

| Step 2 | .142 | |||||||

| PTSD symptoms | 0.123 | 0.029 | 4.245 | < .001 | 0.066 | 0.180 | 0.054 | |

| Mindfulness | − 2.579 | 0.835 | − 3.090 | .002 | − 4.223 | − 0.935 | 0.028 | |

| Step 3 | .046 | |||||||

| PTSD symptoms × Mindfulness | − 0.163 | 0.040 | − 4.037 | < .001 | − 0.243 | − 0.084 | 0.046 |

N = 266 trauma-exposed firefighters. Bonferroni correction applied, p < .025 (α = .05/2). B, unstandardized beta weight; SE, standard error; sr2, squared semi-partial correlation; Pain intensity and pain-related disability reported for the past 3 months, CPGS total subscale scores (Von Korff et al., 1992); Trauma load, total number of event types endorsed on LEC-5 (Weathers et al., 2013); PTSD symptoms, PCL-5 total score (Blevins et al., 2015); Mindfulness, FFMQ total average score (Baer et al., 2006)

Fig. 1.

Pain-related disability: interactive effects of PTSD symptom severity and mindfulness

Regarding pain-related disability, step 1 contributed 8.5% of variance to the model (p < 0.001), and trauma load emerged as a significant correlate (p < 0.001). Step 2 contributed 14.2% of unique variance to the model (sig. F Δ p < 0.001), and both PTSD symptom severity (p < 0.001) and mindfulness (p = 0.002) were incrementally related to pain-related disability. In step 3, the interactive effect of PTSD symptom severity by mindfulness contributed 4.6% of unique variance to the model (sig. F Δ p < 0.001). Simple slope analyses (see Fig. 1) revealed that the association between PTSD symptom severity and pain-related disability was significant for firefighters with low mindfulness (i.e., 1 SD below the total average FFMQ score [2.91; B = − 0.25, SE = 0.07, p < 0.001], but not for those with high mindfulness (i.e., 1 SD above the total average FFMQ score [3.90;B = − 0.04, SE = 0.13, p = 0.744]). The Johnson-Neyman technique indicated that the transition of FFMQ total average scores at which the relationship between PTSD symptom severity and pain-related disability becomes significant was 3.32, with 45.49% of the sample with scores below this value.

Main and Interactive Effects of Mindfulness Facets

Please see Table 4 for a summary of the post hoc analyses. Five post hoc analyses were conducted to examine each mindfulness facet (observing, describing, acting with awareness, non-judging of inner experience, and nonreactivity to inner experience), in turn, as moderator of the association between PTSD symptom severity and pain-related disability. Covariates included age, years in the fire service, and trauma load.

Table 4.

Main and interactive effects of PTSD symptom severity and mindfulness facets on pain-related disability

| ΔR 2 | B | SE | t | p | 95% CI | sr 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observing | ||||||||

| Step 1 | .085 | |||||||

| Age | − 0.066 | 0.066 | − 1.003 | .317 | − 0.196 | 0.064 | 0.003 | |

| Years in the fire service | − 0.012 | 0.071 | − 0.168 | .866 | − 0.152 | 0.128 | 0.000 | |

| Trauma load | 0.758 | 0.159 | 4.765 | < .001 | 0.445 | 1.072 | 0.080 | |

| Step 2 | .116 | |||||||

| PTSD symptoms | 0.162 | 0.027 | 6.095 | < .001 | 0.110 | 0.215 | 0.114 | |

| Observing | − 0.387 | 0.417 | − 0.929 | .354 | − 1.209 | 0.434 | 0.003 | |

| Step 3 | .033 | |||||||

| PTSD symptoms × Observing | − 0.086 | 0.026 | − 3.321 | .001 | − 0.137 | − 0.035 | 0.033 | |

| Describing | ||||||||

| Step 2 | .115 | |||||||

| PTSD symptoms | 0.154 | 0.028 | 5.452 | < .001 | 0.099 | 0.210 | 0.667 | |

| Describing | − 0.356 | 0.461 | − 0.772 | .441 | − 1.265 | 0.553 | 0.746 | |

| Step 3 | .045 | |||||||

| PTSD symptoms × Describing | − 0.107 | 0.027 | − 3.915 | < .001 | − 0.161 | − 0.053 | 0.045 | |

| Awareness | ||||||||

| Step 2 | .146 | |||||||

| PTSD symptoms | 0.128 | 0.028 | 4.583 | < .001 | 0.073 | 0.183 | 0.062 | |

| Awareness | − 1.605 | 0.487 | − 3.296 | .001 | − 2.564 | − 0.646 | 0.032 | |

| Step 3 | .007 | |||||||

| PTSD symptoms × Awareness | − 0.043 | 0.027 | − 1.582 | .115 | − 0.096 | 0.011 | 0.007 | |

| Nonjudging | ||||||||

| Step 2 | .128 | |||||||

| PTSD symptoms | 0.138 | 0.029 | 4.829 | < .001 | 0.082 | 0.194 | 0.071 | |

| Nonjudging | − 1.019 | 0.470 | − 2.171 | .031 | − 1.944 | − 0.095 | 0.014 | |

| Step 3 | .006 | |||||||

| PTSD symptoms × Nonjudging | − 0.036 | 0.026 | − 1.390 | .166 | − 0.087 | 0.015 | 0.006 | |

| Nonreactivity | ||||||||

| Step 2 | .119 | |||||||

| PTSD symptoms | 0.155 | 0.027 | 5.737 | < .001 | 0.102 | 0.208 | 0.100 | |

| Nonreactivity | − 0.637 | 0.469 | − 1.359 | .175 | − 1.560 | 0.286 | 0.006 | |

| Step 3 | .058 | |||||||

| PTSD symptoms × Nonreactivity | − 0.135 | 0.030 | − 4.530 | < .001 | − 0.193 | − 0.076 | 0.059 |

N = 266 trauma-exposed firefighters. Bonferroni correction applied, p < .01 (α = .05/5). B, unstandardized beta weight; SE, standard error; sr2, squared semi-partial correlation; Pain intensity and pain-related disability reported for the past 3 months, CPGS total subscale scores (Von Korff et al., 1992); Trauma load, total number of event types endorsed on LEC-5 (Weathers et al., 2013); PTSD symptoms, PCL-5 total score (Blevins et al., 2015); Observing, Describing, Awareness, Nonjudging, and Nonreacting, FFMQ subscale total average scores (Baer et al., 2006)

Regarding main and interactive effects of PTSD symptom severity and observing on pain-related disability, step 2 of the model contributed 11.6% of unique variance (sig.F Δ p < 0.001), and PTSD symptom severity demonstrated a significant main effect. At step 3, the interactive effect of PTSD symptom severity and observing contributed 3.3% of unique variance to the model (sig. FΔ p = 0.001). Simple slope analyses revealed that associations between PTSD and pain-related disability were significant for firefighters with low observing skills (i.e., 1 SD below the average FFMQ observing subscale score [2.02; B = 0.32, SE = 0.43, p < 0.001], but not for those with high observing skills (i.e., 1 SD above [3.84; B = 0.024, SE = 0.73, p = 0.744]).

Regarding main and interactive effects of PTSD symptom severity and describing on pain-related disability, step 2 contributed 11.5% of unique variance (sig. F Δ p = 0.001), and PTSD symptom severity demonstrated a significant main effect. At step 3, the interactive effect of PTSD symptom severity and describing was significant and contributed 4.5% of unique variance to the model (sig. FΔ p < 0.001). Simple slope analyses revealed that associations between PTSD and pain-related disability were significant for firefighters with low describing skills (i.e., 1 SD below the average FFMQ describing score [2.55; B = 0.34, SE = 0.05, p < 0.001], but not for those with high describing skills (i.e., 1 SD above [4.28; B = 0.19, SE = 0.11, p = 0.086]).

Regarding main and interactive effects of PTSD symptom severity and acting with awareness on pain-related disability, step 2 contributed 14.6% of unique variance (sig. F Δ p < 0.001), and both PTSD symptom severity and acting with awareness demonstrated significant main effects. In step 3 of the model, the interaction between PTSD symptom severity and acting with awareness was not significant (sig. F Δ p = 0.115).

Regarding main and interactive effects of PTSD symptom severity and nonjudging of inner experience on pain-related disability, step 2 contributed 12.8% of unique variance (sig.F Δ p < 0.001), and PTSD symptom severity demonstrated a significant main effect. In step 3, the interaction between PTSD symptom severity and nonjudging of inner experience was not significant (sig. F Δ p = 0.166).

Regarding main and interactive effects of PTSD symptom severity and nonreactivity to inner experience on pain-related disability, step 2 of the model contributed 11.9% of unique variance (sig. F Δ p < 0.001), and PTSD symptom severity demonstrated a significant main effect. In step 3, the interactive effect of PTSD symptom severity and nonreactivity to inner experience was significantly related to pain-related disability and contributed 5.8% of unique variance (sig. FΔ p < 0.001). Simple slope analyses revealed that associations between PTSD and pain-related disability were significant for firefighters with low nonreactivity to inner experience (i.e., 1 SD below the average FFMQ nonreactivity to inner experience score [2.40; B = 0.27, SE = 0.06,p < 0.001] as well as those with high nonreactivity to inner experience (i.e., 1 SD above [4.02; B = 0.12, SE = 0.05, p = 0.012]).

Discussion

The current investigation sought to examine the main and interactive effects of PTSD symptom severity with mindfulness with regard to (a) pain intensity and (b) pain-related disability among firefighters. Post hoc exploratory analyses were conducted to examine the main and interactive effects of each of the five mindfulness facets in terms of the significant outcomes from the main analyses (i.e., pain-related disability). Hypotheses were partially supported, and all outcomes were documented after controlling for theoretically relevant covariates (i.e., age, number of years in the fire service, and trauma load).

First, significant main effects emerged for PTSD symptom severity on both pain intensity and disability, above and beyond the variance contributed by covariates. As predicted, firefighters with greater PTSD symptom severity evinced greater pain intensity and pain-related disability. These findings are consistent with previous work documenting significant associations between PTSD symptomatology and both the experience of pain as well as pain-related disability across various populations (Benedict et al., 2020). Findings suggest that PTSD may amplify pain associated with acute and/or chronic ailments and increase the likelihood of disability from these ailments. Alternatively, pain-inducing ailments and disability resulting from trauma exposure and work-related injuries may increase vulnerability to the development or maintenance of PTSD symptomatology as posited by shared vulnerability theories (Asmundson & Hadjistavropolous, 2006). Longitudinal research methodologies are needed to further replicate and extend these findings, particularly among firefighter populations.

Second, a significant main effect was documented for mindfulness on pain-related disability, but not for pain intensity. That is, firefighters with lower levels of mindfulness endorsed greater levels of pain-related disability but did not endorse significantly greater levels of pain intensity, contrary to hypotheses. Significant associations between mindfulness and pain-related disability are consistent with extant literature (McCracken et al., 2007; Veehof et al., 2016) and suggest that mindfulness-based approaches to address work limitations among active firefighters may facilitate returning to duty and improving overall functioning. Unexpectedly, the association between mindfulness and pain intensity was not significant and was unexpected given previous work documenting robust associations between these two constructs (McCracken et al., 2007; Reiner et al., 2013). It is possible that firefighters underreported the intensity of pain due to potential stigma associated with disclosing adverse health information (e.g., Haugen et al., 2017; Johnson et al., 2020), suggesting that pain-related disability may serve as a better proxy for pain outcomes in firefighter populations (e.g., Ballantyne & Sullivan, 2015). Conversely, pain intensity among firefighters may be suppressed due to the intensive training provided in the fire service focused on managing job-related discomfort (e.g., carrying and wearing heavy equipment and working in arduous environments; Peterson et al., 2008). It may also be the case that firefighters with low levels of mindfulness may, by definition, have a diminished ability to be aware of and accurately report nociception pain experiences, and as a result, may underreport pain-related symptom. Thus, further work is needed to better elucidate these mixed results and conclusions to enhance our understanding of pain outcomes in the fire service.

Third, an interactive effect of PTSD symptom severity by mindfulness was significantly associated with pain-related disability, but not pain intensity, after accounting for the variance contributed by covariates as well as main effects. Consistent with hypotheses, higher levels of PTSD symptom severity and lower levels of mindfulness were associated with greater levels of pain-related disability. In other words, low levels of mindfulness may exacerbate (i.e., moderate) relations between PTSD symptomatology and pain-related disability in firefighters, which is consistent with past research among similar high-risk groups (i.e., military veterans; Dahm et al., 2015; Meyer et al., 2018). These findings suggest that firefighters with heightened PTSD symptomatology and a reduced ability to remain nonreactive and non-judgmental to adverse emotional states (i.e., low mindfulness) may face greater difficulties in regulating PTSD-related affective states (e.g., Martinez-Calderon et al., 2018), and in turn, experience increased pain-related disability (e.g., Lewis et al., 2012; Sharp & Harvey, 2001). Conversely, heightened mindfulness may buffer or dampen the association between PTSD and pain-related disability, highlighting the potential clinical utility of mindfulness-based skills programs in the fire service. However, contrary to hypotheses, firefighters with higher levels of PTSD symptomatology and lower levels of mindfulness did not endorse significantly greater levels of pain intensity. That is, despite significant mindfulness-pain intensity relations at the bivariate level (r = − 0.26) and well-documented associations in the literature (e.g., McClintock et al., 2019), mindfulness did not evince a significant main effect on pain intensity. It will be important for future work to further examine mindfulness-pain associations, particularly in the context of PTSD in first responders.

Finally, post hoc exploratory analyses were conducted to examine the main and interactive effects of each of the five mindfulness facets (i.e., observing, describing, acting with awareness, non-judging of inner experience, and nonreactivity to inner experience) with pain-related disability. Nonjudging of inner experience was not related to pain-related disability at the level of main or interactive effect, although it demonstrated a significant negative association (r = − 0.30) at the bivariate level. Acting with awareness demonstrated a significant incremental association with pain-related disability. However, only observing, describing, and nonreactivity to inner experience evinced interactive effects with PTSD symptom severity regarding pain-related disability. While the magnitudes of these effects were within a similar range (3.3–5.8% of unique variance), the interaction of PTSD symptom severity and nonreactivity was the most robust (ΔR2= 0.058). These findings underscore the unique associations of each mindfulness facet with the interference of pain on daily functioning and the ability to work among firefighters. For instance, firefighters with low levels of acting with awareness (e.g., a reduced ability to engage fully in the present moment) may have difficulty managing pain-related disability at work and at home. Firefighters with both low levels of describing (e.g., a limited capacity to identify and label internal experiences and emotions), observing, or nonreactivity to inner experience and high levels of PTSD symptomatology may be especially likely to endorse greater pain-related interference on daily functioning. It is important to note that while distinct mindfulness facets and pain associations have been documented in past literature (e.g., Nigol & Di Benedetto, 2020), no published studies to date have examined these associations in firefighting populations within the context of PTSD symptomatology. Given the exploratory nature of these analyses, more work focused on examining unique relations among PTSD symptoms, mindfulness facets, and pain-related outcomes among firefighters is necessary before more definitive conclusions may be drawn.

Limitations and Future Directions

Study limitations should be noted. First, study findings are limited in scope and generalizability due to the cross-sectional research design, and consequently, explanations regarding causality and temporality of outcomes are restricted. Research methodologies that implement experimental or longitudinal methodologies should be prioritized to investigate possible temporal and/or causal associations between PTSD and mindfulness. Second, the parent study relied exclusively on self-report measures of the variables of interest, and thus, we cannot disqualify the influence of reporting and self-selection biases as well as the effect of method variance on participant responses. It is imperative for future work to incorporate clinician-administered measures (e.g., semi-structured interviews) to validate pain-related experiences and disability as well as PTSD symptomatology in order to extend these findings. Third, current study’s sample was primarily composed of white, male fire-fighters; therefore, it is crucial for future research to recruit more firefighters from diverse racial and ethnic groups and those who identify as women, given the increased risk of injury among female firefighters working in a male-dominated field (e.g., Hollerbach et al., 2017; Sinden et al., 2013). Finally, although study confidentiality was described during the informed consent process, firefighters within the current sample may have underreported the presence and severity of their PTSD symptoms and pain-related experiences due to potential stigma (e.g., Haugen et al., 2017; Johnson et al., 2020) and study setting effects (i.e., completing surveys while on duty; Gulliver et al., 2019).

Firefighting is an inherently dangerous profession associated with high rates of trauma exposure, PTSD symptomatology, and both acute and chronic pain. These findings build upon previous research and underscore the salience of pain and associated disability among firefighters as well as the unique associations between PTSD symptomatology and pain outcomes among this population. Given the prevalence of PTSD and pain in firefighters, it will be important to examine the role of other transdiagnostic, cognitive-affective factors associated with PTSD-pain associations, such as distress tolerance (i.e., the capacity to endure adverse physical and/or psychological states; Leyro et al., 2010). Furthermore, future work should elucidate and assess the impact of specific trauma exposure types (e.g., natural disasters) and PTSD symptom clusters on rates of pain-related disability and associated consequences (e.g., rates of early retirement and/or sick leave), using experimental and/or longitudinal methodologies.

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported, in part, by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities of the National Institutes of Health to the University of Houston (Vujanovic; U54MD015946). This work was also supported, in part, by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism awards to the first author (Lebeaut; NIAAA F31AA029600), the second author (Zegel; NIAAA F31AA029022), and the fourth author (Rogers; NIAAA F31AA028694). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Ethics Statement This study was approved by the University of Houston’s Institutional Review Board. All procedures performed in the study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent Statement All participants gave their informed consent for participation and had the opportunity to review the form as well as ask questions related to the consent form. Participants were free to decide whether to participate and that they could discontinue participation at any time without penalty. Participants were also provided the opportunity to decline participation during the informed consent procedure. All consent procedures were approved by the university institutional review board.

Conflict of Interest The authors declare no competing interests.

Data Availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: Author [Google Scholar]

- Andersen TE, & Vaegter HB (2016). A 13-weeks mindfulness based pain management program improves psychological distress in patients with chronic pain compared with waiting list controls. Clinical Practice & Epidemiology in Mental Health, 12, 49–58. 10.2174/1745017901612010049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asmundson GJG, & Hadjistavropolous HD (2006). Addressing shared vulnerability for comorbid PTSD and chronic pain: A cognitive-behavioral perspective. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 13(1),8–16. 10.1016/j.cbpra.2005.03.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Asmundson GJ, Coons MJ, Taylor S, & Katz J (2002). PTSD and the experience of pain: Research and clinical implications of shared vulnerability and mutual maintenance models. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 47(10), 930–937. 10.1177/070674370204701004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer RA, Smith GT, Hopkins J, Krietemeyer J, & Toney L (2006). Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment, 13(1), 27–45. 10.1177/1073191105283504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer RA, Smith GT, Lykins E, Button D, Krietemeyer J, Sauer S, Walsh E, Duggan D, & Williams JM (2008). Construct validity of the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire in meditating and nonmeditating samples. Assessment, 15(3), 329–342. 10.1177/1073191107313003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballantyne JC, & Sullivan MD (2015). Intensity of chronic pain–The wrong metric? The New England Journal of Medicine, 373(22), 2098–2099. 10.1056/NEJMp1507136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benedict TM, Keenan PG, Nitz AJ, & Moeller-Bertram T (2020). Post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms contribute to worse pain and health outcomes in veterans with PTSD compared to those without: A systematic review With meta-analysis. Military Medicine, 185(9–10), e1481–e1491. 10.1093/milmed/usaa052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blevins CA, Weathers FW, Davis MT, Witte TK, & Domino JL (2015). The posttraumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): Development and initial psychometric evaluation. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 28(6), 489–498. 10.1002/jts.22059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bos J, Mol E, Visser B, & Frings-Dresen M (2004). Risk of health complaints and disabilities among Dutch firefighters. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health, 77(6), 373–382. 10.1007/s00420-004-0537-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bovin MJ, Marx BP, Weathers FW, Gallagher MW, Rodriguez P, Schnurr PP, & Keane TM (2016). Psychometric properties of the PTSD Checklist for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders - Fifth edition (PCL-5) in veterans. Psychological Assessment, 28(11), 1379–1391. 10.1037/pas0000254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bravo AJ, Pearson MR, Wilson AD, & Witkiewitz K (2018). When traits match states: Examining the associations between self-report trait and state mindfulness following a state mindfulness induction. Mindfulness (N Y), 9(1), 199–211. 10.1007/s12671-017-0763-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canady BE, ZulligK J, Brumage MR, & Goerling RJ (2021). Intensive mindfulness-based resilience training in first responders: A pilot study. Health Behavior and Policy Review, 8(1), 60–70. 10.14485/HBPR.8.1.6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carleton RN, Afifi TO, Taillieu T, Turner S, El-Gabalawy R, Sareen J, & Asmundson GJG (2018). Anxiety-related psychopathology and chronic pain comorbidity among public safety personnel. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 55, 48–55. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2018.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahm KA, Meyer EC, Neff KD, Kimbrel NA, Gulliver SB, & Morissette SB (2015). Mindfulness, self-compassion, posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms, and functional disability in U.S. Iraq and Afghanistan war veterans. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 28(5), 460–464. 10.1002/jts.22045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denkova E, Zanesco AP, Rogers SL, & Jha AP (2020). Is resilience trainable? An initial study comparing mindfulness and relaxation training in firefighters. Psychiatry Research, 285, 112794. 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Tumi H, Johnson MI, Dantas PBF, Maynard MJ, & Tashani OA (2017). Age-related changes in pain sensitivity in healthy humans: A systematic review with meta-analysis. European Journal of Pain, 21(6), 955–964. 10.1002/ejp.1011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher S (2005). Physical limitations and musculoskeletal complaints associated with work in unusual or restricted postures: A literature review. Journal of Safety Research, 36(1), 51–61. 10.1016/j.jsr.2004.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein E, McDonnell C, Atchley R, Dorado K, Bedford C,Brown RL, & Zgierska AE (2019). The impact of psychological interventions on posttraumatic stress disorder and pain symptoms: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Clinical Journal of Pain, 35(8), 703–712. 10.1097/ajp.0000000000000730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gulliver SB, Pennington ML, Torres VA, Steffen LE, Mardikar A, Leto F, Ostiguy WJ, Zimering RT, & Kimbrel NA (2019). Behavioral health programs in fire service: Surveying access and preferences. Psychological Services, 16(2), 340–345. 10.1037/ser0000222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey SB, Milligan-Saville JS, Paterson HM, Harkness EL,Marsh AM, Dobson M, Kemp R, & Bryant RA (2016). The mental health of fire-fighters: An examination of the impact of repeated trauma exposure. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 50(7), 649–658. 10.1177/0004867415615217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haugen PT, McCrillis AM, Smid GE, & Nijdam MJ (2017). Mental health stigma and barriers to mental health care for first responders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 94, 218–229. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2017.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilton L, Hempel S, Ewing BA, Apaydin E, Xenakis L, Newberry S, Colaiaco B, Maher AR, Shanman RM, Sorbero ME, & Maglione MA (2017). Mindfulness meditation for chronic pain: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 51(2), 199–213. 10.1007/s12160-016-9844-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollerbach BS, Heinrich KM, Poston WSC, Haddock CK,Kehler AK, & Jahnke SA (2017). Current female firefighters’ perceptions, attitudes, and experiences with injury. International Fire Service Journal of Leadership and Management,11, 41–47. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopwood TL, & Schutte NS (2017). A meta-analytic investigation of the impact of mindfulness-based interventions on post traumatic stress. Clinical Psychology Review, 57, 12–20. 10.1016/j.cpr.2017.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corporation. (2017). IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 25.0 IBM Corp. [Google Scholar]

- Jahnke SA, Poston WS, Haddock CK, & Jitnarin N (2013). Injury among a population based sample of career firefighters in the central USA. Injury Prevention, 19(6), 393–398. 10.1136/injuryprev-2012-040662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahnke SA, Poston WS, Haddock CK, & Murphy B (2016). Firefighting and mental health: Experiences of repeated exposure to trauma. Work, 53(4), 737–744. 10.3233/wor-162255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson CC, Vega L, Kohalmi AL, Roth JC, Howell BR,& Van Hasselt VB (2020). Enhancing mental health treatment for the firefighter population: Understanding fire culture, treatment barriers, practice implications, and research directions. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 51(3), 304–311. 10.1037/pro0000266 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Joyce S, Shand F, Bryant RA, Lal TJ, & Harvey SB (2018). Mindfulness-based resilience training in the workplace: Pilot study of the internet-based resilience@work (RAW) mindfulness program. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 20(9), e10326. 10.2196/10326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn JR, Collinge W, & Soltysik R (2016). Post-9/11 veterans and their partners improve mental health outcomes with a self-directed mobile and web-based wellness training program: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 18(9), e255. 10.2196/jmir.5800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsavouni F, Bebetsos E, Malliou P, & Beneka A (2016). The relationship between burnout, PTSD symptoms and injuries in firefighters. Occupational Medicine, 66(1), 32–37. 10.1093/occmed/kqv144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kearney DJ, Simpson TL, Malte CA, Felleman B, Martinez ME, & Hunt SC (2016). Mindfulness-based stress reduction in addition to usual care is associated with improvements in pain, fatigue, and cognitive failures among veterans with Gulf War illness. The American Journal of Medicine, 129(2), 204–214. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.09.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick DG, Resnick HS, Milanak ME, Miller MW, Keyes KM, & Friedman MJ (2013). National estimates of exposure to traumatic events and PTSD prevalence using DSM-IV and DSM-5 criteria. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 26(5), 537–547. 10.1002/jts.21848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim MG, Seo J, Kim K, & Ahn YS (2017). Nationwide firefighter survey: The prevalence of lower back pain and its related psychological factors among Korean firefighters. International Journal of Occupational Safety and Ergonomics, 23(4), 447–456. 10.1080/10803548.2016.1219149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebeaut A, Zegel M, Leonard SJ, Bartlett BA, & Vujanovic AA (2020). Examining transdiagnostic factors among firefighters in relation to trauma exposure, probable PTSD, and probable alcohol use disorder. Journal of Dual Diagnosis. 10.1080/15504263.2020.1854411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JH, Lee D, Kim J, Jeon K, & Sim M (2017). Duty-telated trauma exposure and posttraumatic stress symptoms in professional firefighters. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 30(2), 133–141. 10.1002/jts.22180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard SJ, & Vujanovic AA (2021). Thwarted belongingness and PTSD symptom severity among firefighters: The role of emotion regulation difficulties. Behavior Modification, 0(0),01454455211002105. 10.1177/01454455211002105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis JD, Wassermann EM, Chao W, Ramage AE, Robin DA, & Clauw DJ (2012). Central sensitization as a component of post-deployment syndrome. NeuroRehabilitation, 31(4), 367–372. 10.3233/NRE-2012-00805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leyro TM, Zvolensky MJ, & Bernstein A (2010). Distress tolerance and psychopathological symptoms and disorders: A review of the empirical literature among adults. Psychological Bulletin,136(4), 576–600. 10.1037/a0019712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahan AL, & Ressler KJ (2012). Fear conditioning, synaptic plasticity and the amygdala: Implications for posttraumatic stress disorder. Trends in Neurosciences, 35(1), 24–35. 10.1016/j.tins.2011.06.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin CE, Bartlett BA, Reddy MK, Gonzalez A, & Vujanovic AA (2018). Associations between mindfulness facets and PTSD symptom severity in psychiatric inpatients. Mindfulness (N Y), 9(5), 1571–1583. 10.1007/s12671-018-0904-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Calderon J, Meeus M, Struyf F, Miguel Morales-Asencio J, Gijon-Nogueron G, & Luque-Suarez A (2018). The role of psychological factors in the perpetuation of pain intensity and disability in people with chronic shoulder pain: A systematic review. British Medical Journal Open, 8(4), e020703. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAndrew LM, Lu SE, Phillips LA, Maestro K, & Quigley KS (2019). Mutual maintenance of PTSD and physical symptoms for Veterans returning from deployment. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 10(1), 1608717. 10.1080/20008198.2019.1608717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClintock AS, McCarrick SM, Garland EL, Zeidan F, & Zgierska AE (2019). Brief mindfulness-based interventions for acute and chronic pain: A systematic review. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 25(3), 265–278. 10.1089/acm.2018.0351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCracken LM, Gauntlett-Gilbert J, & Vowles KE (2007). The role of mindfulness in a contextual cognitive-behavioral analysis of chronic pain-related suffering and disability. Pain, 131(1–2), 63–69. 10.1016/j.pain.2006.12.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer EC, Zimering R, Daly E, Knight J, Kamholz BW, & Gulliver SB (2012). Predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder and other psychological symptoms in trauma-exposed firefighters. Psychological Services, 9(1), 1–15. 10.1037/a0026414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer EC, Frankfurt SB, Kimbrel NA, DeBeer BB, Gulliver SB, & Morrisette SB (2018). The influence of mindfulness, self-compassion, psychological flexibility, and posttraumatic stress disorder on disability and quality of life over time in war veterans. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 74(7), 1272–1280. 10.1002/jclp.22596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morey L (2007). Personality Assessment Inventory professional manual (2nd ed.). Psychological Assessment Resources. [Google Scholar]

- Nazari G, MacDermid JC, & Cramm H (2020a). Prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders among Canadian firefighters: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Military, Veteran and Family Health, 6(1), 83–97. 10.3138/jmvfh-2019-0024 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nazari G, Osifeso TA, & MacDermid JC (2020b). Distribution of number, location of pain and comorbidities, and determinants of work limitations among firefighters. Rehabilitation Research and Practice, 2020, 1942513. 10.1155/2020/1942513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negm A, MacDermid JC, Sinden K, D’Amico R, Lomotan M,& MacIntyre NJ (2017). Prevalence and distribution of musculoskeletal disorders in firefighters are influenced by age and length of service. Journal of Military, Veteran and Family Health, 3(2), 33–41. 10.3138/jmvfh.2017-0002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nigol SH, & Di Benedetto M (2020). The relationship between mindfulness facets, depression, pain severity and pain interference. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 25(1), 53–63. 10.1080/13548506.2019.1619786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niles BL, Mori DL, Polizzi C, Pless Kaiser A, Weinstein ES, Gershkovich M, & Wang C (2018). A systematic review of randomized trials of mind-body interventions for PTSD. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 74(9), 1485–1508. 10.1002/jclp.22634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Outcalt SD, Kroenke K, Krebs EE, Chumbler NR, Wu J,Yu Z, & Bair MJ (2015). Chronic pain and comorbid mental health conditions: Independent associations of posttraumatic stress disorder and depression with pain, disability, and quality of life. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 38(3), 535–543. 10.1007/s10865-015-9628-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson MD, Dodd DJ, Alvar BA, Rhea MR, & Favre M(2008). Undulation training for development of hierarchical fitness and improved firefighter job performance. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 22(5), 1683–1695. 10.1519/JSC.0b013e31818215f4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polusny MA, Erbes CR, Thuras P, Moran A, Lamberty GJ, Collins RC, Rodman JL, & Lim KO (2015). Mindfulness-based stress reduction for posttraumatic stress disorder among veterans: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA, 314(5), 456–465. 10.1001/jama.2015.8361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raichle KA, Osborne TL, Jensen MP, & Cardenas D (2006). The reliability and validity of pain interference measures in persons with spinal cord injury. The Journal of Pain, 7(3), 179–186. 10.1016/j.jpain.2005.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauch SL, Shin LM, & Phelps EA (2006). Neurocircuitry models of posttraumatic stress disorder and extinction: Human neuroimaging research–past, present, and future. Biological Psychiatry,60(4), 376–382. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reffi AN, Pinciotti CM, Darnell BC, & Orcutt HK(2019). Trait mindfulness and PTSD symptom clusters: Considering the influence of emotion dysregulation. Personality and Individual Differences, 137, 62–70. 10.1016/j.paid.2018.08.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reiner K, Tibi L, & Lipsitz JD (2013). Do mindfulness-based interventions reduce pain intensity? A critical review of the literature. Pain Medicine, 14(2), 230–242. 10.1111/pme.12006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp TJ, & Harvey AG (2001). Chronic pain and posttraumatic stress disorder: Mutual maintenance? Clinical Psychology Review, 21(6), 857–877. 10.1016/s0272-7358(00)00071-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinden K, MacDermid J, Buckman S, Davis B, Matthews T, & Viola C (2013). A qualitative study on the experiences of female firefighters. Work, 45(1), 97–105. 10.3233/wor-121549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siqveland J, Hussain A, Lindstrom JC, Ruud T, & Hauff E (2017). Prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder in persons with chronic pain: A meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 164. 10.3389/fpsyt.2017.00164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skeffington PM, Rees CS, & Mazzucchelli T (2017). Trauma exposure and post-traumatic stress disorder within fire and emergency services in Western Australia. Australian Journal of Psychology, 69(1), 20–28. 10.1111/ajpy.12120 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Soteriades ES, Psalta L, Leka S, & Spanoudis G (2019). Occupational stress and musculoskeletal symptoms in firefighters. International Journal of Occupational Medicine and Environmental Health, 32(3), 341–352. 10.13075/ijomeh.1896.01268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley IH, Boffa JW, Tran JK, Schmidt NB, Joiner TE, & Vujanovic AA (2019). Posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and mindfulness facets in relation to suicide risk among firefighters. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 75(4), 696–709. 10.1002/jclp.22748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomaka J, Magoc D, Morales-Monks SM, & Reyes AC (2017). Posttraumatic stress symptoms and alcohol-related outcomes among municipal firefighters. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 30(4), 416–424. 10.1002/jts.22203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veehof MM, Trompetter HR, Bohlmeijer ET, & Schreurs KM (2016). Acceptance-and mindfulness-based interventions for the treatment of chronic pain: A meta-analytic review. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 45(1), 5–31. 10.1080/16506073.2015.1098724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Korff M, Ormel J, Keefe FJ, & Dworkin SF (1992). Grading the severity of chronic pain. Pain, 50, 133–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weathers FW, Blake DD, Schnurr PP, Kaloupek DG, Marx BP, & Keane TM (2013). The Life Events Checklist for DSM-5 (LEC-5). Retrieved October 20, 2018,from the National Center for PTSD at www.ptsd.va.gov

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author upon request.