Abstract

New variants of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) appear rapidly every few months. They have showed powerful adaptive ability to circumvent the immune system. To further understand SARS-CoV-2's adaptability so as to seek for strategies to mitigate the emergence of new variants, herein we investigated the viral adaptation in the presence of broadly neutralizing antibodies and their combinations. First, we selected four broadly neutralizing antibodies, including pan-sarbecovirus and pan-betacoronavirus neutralizing antibodies that recognize distinct conserved regions on receptor-binding domain (RBD) or conserved stem-helix region on S2 subunit. Through binding competition analysis, we demonstrated that they were capable of simultaneously binding. Thereafter, a replication-competent vesicular stomatitis virus pseudotyped with SARS-CoV-2 spike protein was employed to study the viral adaptation. Twenty consecutive passages of the virus under the selective pressure of individual antibodies or their combinations were performed. It was found that it was not hard for the virus to adapt to broadly neutralizing antibodies, even for pan-sarbecovirus and pan-betacoronavirus antibodies. The virus was more and more difficult to escape the combinations of two/three/four antibodies. In addition, mutations in the viral population revealed by high-throughput sequencing showed that under the selective pressure of three/four combinational antibodies, viral mutations were not prone to present in the highly conserved region across betacoronaviruses (stem-helix region), while this was not true under the selective pressure of single/two antibodies. Importantly, combining neutralizing antibodies targeting RBD conserved regions and stem helix synergistically prevented the emergence of escape mutations. These studies will guide future vaccine and therapeutic development efforts and provide a rationale for the design of RBD-stem helix tandem vaccine, which may help to impede the generation of novel variants.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, Adaptation, Spike protein, Stem helix, Broadly neutralizing antibody

Highlights

-

•

Even the extremely broadly neutralizing antibody was relatively easy to be escaped.

-

•

Increasing number of combinational antibodies gradually enhance their resistance to viral evasion.

-

•

RBD- and stem helix-targeted antibodies synergistically prevent evasion.

-

•

Different evolutionary tendency under selective pressure of single or combinational antibodies was shown.

1. Introduction

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has manifested powerful adaptability in circumventing the immune system. Among the variants in early 2021, the B.1.351 variant [designated as Beta variant of concern (VOC)] was the most vaccine-resistant variant that co-occurred with K417N/E484K/N501Y substitution in receptor-binding domain (RBD) and Δ242–244 deletion in N-terminal domain (NTD) (Wang P. et al., 2021). Subsequently, a new variant B.1.617.2 (Delta VOC) emerged in India, akin to the Beta VOC, also posed a great challenge to vaccine efficacy due to the presence of L452R/T478K mutations (Wall et al., 2021). In late 2021, the emergence of Omicron VOC accompanied with more than 30 mutations in spike protein alone, has greatly exceeded initial anticipation of the virus (Viana et al., 2022). Owing to its greatly altered antigenicity, Omicron exhibited unprecedented capability to escape the majority of vaccine-mediated immunity and antibody-based therapies (Cao et al., 2022a; Liu et al., 2022; Planas et al., 2022). And at the time of manuscript preparation, a study showed that Omicron sublineages BA.2.12.1 (emerged in the United States) and BA.4/5 (emerged in South Africa) can conduct breakthrough infection into convalescents recovered from Omicron BA.1 infection (Cao et al., 2022b). Shocked by its immune evasion ability, we are unclear how much evolutionary space the virus has left and how broad-spectrum antibodies the virus can escape.

The SARS-CoV-2 spike (S) glycoprotein mediates viral entry into host cells through an S1 subunit that engages host angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor and an S2 subunit serving as membrane fusion machinery (Tortorici and Veesler, 2019). The S1 subunit comprises an NTD and a RBD. Although NTD contains a single supersite of vulnerability, this site is highly variable and frequently deleted in the VOCs (Cerutti et al., 2021; McCallum et al., 2021). The ACE2 receptor-binding motif (RBM) on the RBD is the most immunodominant region and thus is under strong selective pressure, resulting in the accumulation of numerous mutations. However, there is still a supersite at the RBM tip offset from major mutational hotspots in VOCs (Wang L. et al., 2021). In addition to this supersite located within RBM, outside the RBM there are also two relatively conserved antigenic sites. The site IV is on the flank of RBD and targeted by antibodies like REGN-10987 and S309 that were unaffected by Alpha, Beta, Gamma and Delta VOCs (Piccoli et al., 2020). Another highly conserved region is the antigenic site II, which is on the backside of the RBD (Piccoli et al., 2020). This site is cryptic and accessible only when at least two RBDs in the S trimer adopt an open conformation (Piccoli et al., 2020). Compared to S1 subunit, S2 subunit is more functionally and structurally conserved among coronaviruses (Walls et al., 2020a; Shah et al., 2021). Nevertheless, conserved antigenic sites like the fusion peptide and the heptad-repeat 2 regions mainly elicit non-neutralizing antibodies (Li et al., 2021; Sakharkar et al., 2021). All the S2-targeted neutralizing antibodies reported to date recognize the conserved stem-helix region (residues 1140–1165 aa) (Pinto et al., 2021; Sauer et al., 2021; Li W. et al., 2022; Zhou et al., 2022).

In this study, we first selected four representative neutralizing antibodies, which can recognize each conserved epitope (RBM supersite, site IV, site II, and stem-helix region) on spike protein respectively. Among them, the site II-targeted antibody and stem helix-targeted antibody are pan-sarbecovirus and pan-betacoronavirus neutralizing antibodies, respectively. After verifying their proper preparation and simultaneous binding on the spike, we employed a surrogate replication-competent vesicular stomatitis virus pseudotyped with SARS-CoV-2 spike protein (VSV-SARS-CoV-2-S) to interrogate the viral adaptability, in the presence of these four broadly neutralizing antibodies alone or in combinations.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Antibodies

The DNA sequences of the variable domain of heavy chain and light chain of mAbs 2G1 (Ma et al., 2022b), REGN-10987 (Hansen et al., 2020), S2X259 (Tortorici et al., 2021) and CV3-25 (Li W. et al., 2022) were synthesized and cloned into a pcDNA3.4 plasmid backbone with constant domain of heavy/light chain. Plasmids were amplified in E.coli DH5α and isolated with PureLink™ HiPure Plasmid Miniprep Kit (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA) to attain low endotoxin preparation. The plasmids encoding the heavy and light chain of a mAb in pairs were co-transfected into ExpiCHO-S cells (ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA, USA) for transient expression. Cell culture was incubated at 37 °C with humidified atmosphere of 8% CO2 with shaking. ExpiFectamine CHO Enhancer (6 μL per mL of culture) was added ∼ 20 h post-transfection and the temperature was decreased to 32 °C. At day 1 and 5, ExpiCHO Feed (160 μL per mL of culture) was added. Cell culture was harvested on day 12–14. Expression medium was collected after removal of cells by centrifugation (1000 ×g, 4 °C, 10 min). Then the medium was centrifuged again (15,000 ×g, 4 °C, 30 min) and 0.22 μm-filtered before subjected to affinity purification utilizing HiTrap MabSelect SuRe (Cytiva, Marlborough, MA, USA) in AKTA avant (Cytiva). Protein was eluted with 5 column volumes (CV) of 100 mmol/L sodium citrate (pH 3.0). The pH of eluates was adjusted to 7.2 by adding 1 mol/L Tris base. Then the protein solution was exchanged to buffer containing 10 mmol/L histidine-HCl pH 5.5, concentrated by centrifugal filtration and passed through a 0.22 μm filter. Then antibodies were aliquoted and stored at −80 °C freezer prior to use. Concentrations were determined by absorbance at 280 nm using calculated molar extinction coefficients. For long-term storage, antibodies was kept in a formulation buffer containing 10 mmol/L histidine-HCl pH 5.5, 9% trehalose and 0.01% polysorbate 80.

2.2. Cells

HEK-293T cells with ACE2 receptor stable expression (ACE2-293T cells) were established as described in our previous report (Ma et al., 2022a, 2022b; Tang et al., 2022). In brief, a lentiviral system harboring the sequence of ACE2 receptor gene (Genbank ID: NP_001358344.1) was transduced to HEK-293T cells (ATCC, CRL-3216) to attain ACE2-293T cells pool. This cells pool was under selection pressure of 10 μg/mL puromycin (Beyotime Biotechnology, Shanghai, China) for one week. The transfection efficiency was examined by flow cytometry using S1-mFc recombinant protein (Cat# 40591-V05H1, Sino Biological, Beijing, China) as primary antibody and FITC-AffiniPure Goat Anti-Mouse IgG (Cat# 115-095-146, Jackson ImmunoResearch, Chester County, PA, USA) as secondary antibody. Then the cells pool were subjected to fluorescence activated cell sorting with FACS Aria III instrument (BD, Marlborough, MA, USA) to sort out the cell population with top 1% fluorescence intensity. This cells population was retained and expanded for subsequent use. ACE2-293T cells were grown in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium (DMEM) (Gibco, Waltham, MA, USA) high glucose (4500 mg/L) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco), 100 units/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin at 37 °C, 5% CO2. ExpiCHO-S cells (ThermoFisher) were cultured in ExpiCHO Expression Medium (ThermoFisher), 37 °C, 200 ×g, 8% CO2. Vero E6 (ATCC, CRL-1586) were cultured at 37 °C, 5% CO2, in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 units/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. BHK-21 cells (ATCC, CCL-10) were grown in DMEM with 10% FBS, 100 units/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin at 37 °C, 5% CO2.

2.3. Structural analysis of simultaneous binding

To predict the possibility of simultaneous binding, the structure of 2G1 (PDB ID: 7X08), REGN-10987 (PDB ID: 6XDG), S2X259 (PDB ID: 7RAL) and CV3-25 (PDB ID: 7NAB) were downloaded from Protein Data Bank. Then these models were superimposed onto a full-length SARS-CoV-2 spike protein model (Woo et al., 2020) (6VSB_1_1_1) with the Structure Comparison-MatchMaker function of UCSF Chimera software (Pettersen et al., 2004). The superimposed model was inspected if there is steric clash presented.

2.4. Lentiviral particle pseudotyped with SARS-CoV-2 spike

The amino acid sequences of spike protein of Delta, BA.1, BA.2, or BA.4/5 variants with truncation of the last 21 amino acids in the cytoplasmic tail to improve viral titer (Crawford et al., 2021), were codon-optimized and synthesized (General Biological). Then these sequences were cloned into pMD2.G backbone substituting G glycoprotein of vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV-G). HEK-293T cells with 70%–80% confluence in a 10 cm dish were co-transfected 12 μg of plasmid pLVX-Luc2 encoding luciferase reporter genes, 8 μg of plasmid psPAX2 encoding gag and pol, and 4 μg of plasmid pMD2G-ΔG-SpikeΔ21 encoding spike protein of Delta using Lipofectamine 3000 Reagent (Invitrogen). Twelve hours later, the medium was changed to fresh DMEM (Gibco) supplemented with 10% FBS (Gibco) for another 48 h culturing. Medium containing viral particles was harvested and centrifuged at 12,000 ×g for 3 min to remove cell debris. ACE2-293T cells were seeded at a density of 1 × 104 cells/well in a white 96-well tissue culture plate (Corning, Corning, NY, USA) (50 μL/well) one night prior to use. The next day, 5 μL harvested viral supernatant [∼ 10,000 relative luminescence units (RLU)] was diluted with medium (90% DMEM + 10% FBS) to a total volume of 50 μL and then mixed with 50 μL 10-fold serially diluted antibodies/combos (100 μg/mL initial dilution with 9 serial dilutions). Thus, the final starting dilution was 50 μg/mL. The mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 30 min to neutralize the virus. Medium containing equal amount of pseudovirus but no antibodies/combos was used as blank control. The mixture was then added into ACE2-293T cells. All operations were conducted in the biosafety level 2 (BSL-2) lab in Shanghai Jiao Tong University. After an additional 48 h of incubation, the degree of viral entry was determined by luminescence using ONE-Glo™ Luciferase Assay System (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) in the Infinite M200 Pro microplate reader (TECAN, Männedorf, Switzerland). RLUs acquired were normalized to those of blank control wells. Dose-response neutralization curves were fitted with four-parameter nonlinear regression in GraphPad Prism 8 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA).

As for lentiviral particles pseudotyped with spike carrying individual mutations, plasmids pMD2G-ΔG-MutatedSpikeΔ21 encoding individual spike mutants based on wild-type spike sequence were constructed. HEK-293T cells with 70%–80% confluence in a 6-well plate were co-transfected 2.2 μg of plasmid pLVX-Luc2, 1.5 μg of plasmid psPAX2, and 0.7 μg of plasmid pMD2G-ΔG-MutatedSpikeΔ21 using Lipofectamine 3000 Reagent. After pseudoviruses were obtained, neutralization assays were carried out following the procedure described above, except that single or paired antibodies at 80% maximal effective concentration (EC80) concentration were added. Percentage of neutralization was calculated by normalizing the RLUs acquired to those of blank control wells.

2.5. ACE2 competitive inhibition ELISA

Firstly, SARS-CoV-2 S trimer (AcroBiosystems, Beijing, China) was biotinylated using EZ-Link™ Sulfo-NHS-LC-LC-Biotin (ThermoFisher) according to the manufacturer's instruction. Recombinant hACE2-Fc protein was diluted with ELISA Coating Buffer (Solarbio, Beijing, China) to 2 μg/mL and immobilized onto High Binding ELISA 96-Well Plate (BEAVER) with 100 μL per well overnight at 4 °C. The next day, plates were washed for four times with PBST (Solarbio) and blocked with 3% skim milk for 1 h at 37 °C. In order to obtain an optimized S trimer concentration for this experiment, the concentration-dependent binding of biotinylated S trimer was first measured. Serially diluted (initial dilution from 1 μg/mL serially diluted by 3 fold) biotinylated S trimer was added 100 μL per well and incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. After pipetting off the unbound S trimer, plates were washed for four times with PBST and further incubated with 100 μL of 1:2000 diluted Ultrasensitive Streptavidin-Peroxidase Polymer (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) for 1 h at 37 °C. After a final four times washing with PBST, the binding of S trimer with coated hACE2-Fc protein were visualized by adding 100 μL peroxidase substrate TMB Single-Component Substrate solution (Solarbio) and incubating for 15 min in dark. The reaction was terminated by adding 50 μL stop buffer (Solarbio) and the plates were immediately submitted to a microplate reader (TECAN Infinite M200 Pro) to measure the optical density (OD) at 450 nm. Data were analyzed with GraphPad Prism 8 and the EC80 of biotinylated S trimer was calculated by the four-parameter nonlinear regression. After obtaining the EC80 of biotinylated S trimer, a second round of ELISA was performed. The hACE2-Fc protein was coated and the plates were blocked, as previously. Then 50 μL antibodies at the dilution of 100 μg/mL in 1% BSA (Sigma) were added into the coated plates. Biotinylated S trimer at EC80 concentration was subsequently pipetted into the plates. After incubation at 37 °C for 1 h, plates were washed for four times with PBST and incubated with 100 μL of 1:2000 diluted Ultrasensitive Streptavidin-Peroxidase Polymer. After further washing, 100 μL TMB was added, followed by detection of the bound S trimer in the microplate reader. Competitive inhibition rates were calculated by normalizing to the OD values of blank control wells without antibodies.

2.6. Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) analysis

The simultaneous binding of four antibodies onto the spike protein was tested using a BIAcore 8K system (Cytiva) together with CM5 sensor chips (Cytiva). S trimer (AcroBiosystems) was diluted in pH 5.0 Acetate Buffer (Cytiva) and covalently immobilized on chips using an Amine Coupling Kit (Cytiva). After reaching a ∼ 270 RU coupling level (correspond to ∼ 100 RU level of Rmax), the excess antigens were washed away and the unbound sites were blocked with ethanolamine. Antibodies were diluted with HBS-EP buffer (Cytiva) to the concentration of 40 μg/mL. The first antibody was injected at a rate of 20 μL/min for 600 s to reach a saturated binding level, followed by injecting a second antibody into the system. The ascending RU value was monitored to detect the successive binding of four antibodies.

2.7. Recovery of replication-competent VSV-SARS-CoV-2-S virus

The recovery of the infectious VSV-SARS-CoV-2-S virus was carried out in accordance with the plasmid-based rescue method (Whelan et al., 1995; Dieterle et al., 2020). Briefly, a plasmid encoding the VSV antigenome was modified to substitute its native G glycoprotein with the wild-type S glycoprotein of SARS-CoV-2. This pVSV-ΔG-SpikeΔ21 plasmid also contains a GFP-encoding reporter gene. BHK-21 cells were transfected with pVSV-ΔG-SpikeΔ21 plasmid along with plasmids expressing VSV N, P, G and L proteins by using polyethylenimine (PEI) (Polysciences) and infected with a recombinant vaccinia virus expressing T7 RNA polymerase. At day 2–7 post-transfection, the supernatant was collected, filtered through a 0.22-μm filter to remove the vaccina virus, and used to infect fresh BHK-21 cells every day till the appearance of typical cytopathic effect (CPE). Then BHK-21 cells were transfected with a pCAG-VSV-G expression plasmid encoding the VSV-G protein for complementation to amplify the rescued virus. Thereafter, the complemented virus was used to infect Vero E6 cells in the absence of the complementing VSV-G protein. Subsequently, the VSV-SARS-CoV-2-S virus was plaque-purified. Viral supernatants were aliquoted and stored at −80 °C. Viral stocks were amplified in Vero E6 cells. The virus was titrated by plaque assay on Vero E6 cells. The generation of VSV-SARS-CoV-2-S and its use in tissue culture was carried out at BSL-2 lab in Shanghai Jiao Tong University.

2.8. Viral adaptability assay

The Vero E6 cells were seeded (1.25 × 104 cells/well) in the 96-well plate one night before. The following day, the replication-competent VSV-SARS-CoV-2-S virus at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.01 was diluted with medium to a total volume of 50 μL and then incubated with 50 μL 5-fold serially diluted antibodies/combos (100 μg/mL initial dilution with 11 serial dilutions) to neutralize susceptible variants. Thus, the final starting dilution was 50 μg/mL. The mixture was incubated for 30 min at room temperature and then applied to Vero E6 cells. After an incubation of 72 h, the cells were monitored for GFP expression and the wells observed evidence of viral replication (≥ 20% GFP-positive cells) were recorded. Among these recorded wells (containing serial concentrations of antibodies/combos), the well containing the highest concentration of antibodies/combos was chosen for passage. Fifty microliter of supernatant from this well was harvested and incubated with serially diluted antibodies/combos. Then the mixture was used to infect fresh Vero E6 cells in 96-well plates, as before. This procedure was repeated 20 rounds.

To reveal the mutations in escaped viral populations or P20 viral populations, viral supernatants were harvested and then centrifuged twice (1000 ×g, 4 °C, 3 min followed by 15,000 ×g, 4 °C, 3 min). The clarified supernatant containing viral populations was subjected to whole viral genome high-throughput RNA sequencing (Tpbio, Shanghai, China).

2.9. Statistical analysis

The number (n) associated with each dataset in the figures indicates the number of biologically independent samples. The measures of central tendency and dispersion used in each case are indicated in the figure legends. Dose-response neutralization curves were fit to a four-parameter logistic equation by nonlinear regression analysis. Statistical comparisons were carried out by two-tailed heteroscedastic unpaired t-test, one-way or two-way ANOVA as described in the figure legends. The ANOVA statistics were followed by a post hoc correction for family-wise error rate (Tukey test for comparison of each group or Dunnett test for comparison between all groups and control group) as described in the figure legends. Family-wise significance level (alpha) was 0.05. All analyses were carried out in GraphPad Prism 8.

3. Results

3.1. Combination design of four neutralizing antibodies that target distinct conserved epitopes

In order to select four broadly neutralizing antibodies that target distinct epitopes to constitute effective combination to suppress viral evasion, we focused on anti-RBD or anti-S2-stem-helix broadly neutralizing antibodies, rather than anti-NTD neutralizing antibodies that were vulnerable to several VOCs (Cerutti et al., 2021; McCallum et al., 2021). The 485-GFN-487 tip of RBD is offset from mutational hotspots such as K417/L452/E484/T478/N501 in the VOCs. We previously identified a broad ultra-potent monoclonal antibody (mAb) 2G1 from prototypic SARS-CoV-2 convalescent patients that recognizes this supersite (Ma et al., 2022b) (Fig. 1A). The mAb 2G1 broadly neutralized Alpha, Beta, Gamma, Delta variants and efficiently protected mice and rhesus macaques from Beta or Delta variants infection (Ma et al., 2022b). This neutralizing antibody is now under clinical development. Another mAb REGN-10987 approved for Emergency Use Authorization as a component of the REGN-COV cocktail is well-documented about its resistance to the VOCs/VOIs except for Omicron variant (Tao et al., 2021). The site IV region it binds is relatively conserved among the variants. Previous mutational screening demonstrated REGN-10987 is susceptible to mutations in residues N440/K444/V445/G446/P499 (Baum et al., 2020; Starr et al., 2021) (Fig. 1B). The mAb S2X259 developed by Vir Biotechnology is a neutralizing antibody that cross-reacts with spikes from all clades of sarbecovirus (Tortorici et al., 2021). Its complementary determining regions (CDRs) contact RBD residues 369–386, 404–411 and 499–508 that located in the site II region (Fig. 1C). The stem helix region of the S2 subunit is highly conserved among betacoronaviruses (Pinto et al., 2021). By interacting with a linear peptide (residues 1153–1165) in the stem-helix region (Fig. 1D), the mAb CV3-25 interrupts the S2 refolding step that is required for membrane fusion, thus inhibiting virus infection (Li W. et al., 2022). The hACE2 transgenic mice model demonstrated that both neutralizing activity and Fc-mediated effector function of CV3-25 mAb are required for optimal efficacy in vivo (Ullah et al., 2021).

Fig. 1.

Schematic of combination design of four distinct epitopes-targeted antibodies. The epitopes of 2G1 (PDB ID: 7X08), REGN-10987 (PDB ID: 6XDG), S2X259 (PDB ID: 7RAL) and CV3-25 (PDB ID: 7NAB) are shown in (A), (B), (C) and (D), respectively. E Structural analysis predicted that these four mAbs could simultaneously bind to the spike protein without steric clash. The mAbs 2G1, REGN-10987, S2X259, and CV3-25 are colored in red, blue, green, and purple, respectively. The RBD/spike proteins are colored in black. Residues located in the epitope of each mAb are marked. Red circles in “C” represent the regions of residues 369–386 or residues 404–411.

To anticipate the simultaneous binding of these four mAbs, we first downloaded their structural epitope information from the Protein Data Bank (PDB). Then the structures of 2G1 (PDB ID: 7X08), REGN-10987 (PDB ID: 6XDG), S2X259 (PDB ID: 7RAL) and CV3-25 (PDB ID: 7NAB) were superimposed on the full-length SARS-CoV-2 spike protein model (Woo et al., 2020) (6VSB_1_1_1) with UCSF Chimera software (Pettersen et al., 2004). No steric clash between antibodies was observed (Fig. 1E). So we speculated that these four antibodies were able to simultaneously bind on the spike and thus might exert a synergistic effect to mitigate the emergence of new variants.

3.2. Four mAbs preparation, functional validation and simultaneous binding examination

The DNA sequences of heavy chain and light chain variable domains of the three mAbs (except 2G1 prepared previously) were synthesized following the reports in the literatures (Hansen et al., 2020; Tortorici et al., 2021; Li W. et al., 2022) and constructed into plasmids to express in ExpiCHO-S cells system. After 12–14 days, the cell supernatants containing each expressed antibody were purified with MabSelect SuRe column. Finally, the mAbs REGN-10987, S2X259, and CV3-25 were undergone ultrafiltration and concentrated to 3.4 mg/mL, 2.0 mg/mL and 3.0 mg/mL, respectively (3.2 mg/mL for 2G1).

To verify their neutralizing activity, we employed lentiviral particles pseudotyped with spike protein of Delta variant to compare the neutralizing potency of these four individual mAbs side by side, as well as their combinations in parallel. The mAbs 2G1, REGN-10987 and S2X259 all showed similar potent neutralizing activity against the Delta variant with IC50 values ranging from 0.03217 to 0.07718 μg/mL, while CV3-25 exhibited a moderate neutralizing potency (IC50 of 0.8892 μg/mL) (Fig. 2A). However, the combinations of these two/three/four antibodies did not manifest significantly improved neutralizing potency as compared to individual antibodies (Supplementary Fig. S1). To evaluate the neutralizing activity of the combination of these four antibodies against currently circulating SARS-CoV-2 variants, we employed lentiviral particles pseudotyped with spike protein of BA.1, BA.2, or BA.4/5 variant to perform the neutralization assays. We found that the combination of these four antibodies could still broadly neutralize BA.1, BA.2, and BA.4/5 pseudoviruses, albeit some of its component antibodies totally lost efficacy against these variants (REGN-10987 failed to neutralize BA.1; 2G1 and S2X259 failed to neutralize BA.2 and BA.4/5) (Fig. 2B). We then validated their mode of action by ACE2 competitive inhibition ELISA assay. All these three RBD-targeted mAbs exert their neutralization ability through inhibiting ACE2 receptor binding (Fig. 2C), which was consistent with their original reports (Hansen et al., 2020; Tortorici et al., 2021; Ma et al., 2022b). These results together indicate that these four mAbs were properly prepared as reported in the literatures (Hansen et al., 2020; Tortorici et al., 2021; Li W. et al., 2022; Ma et al., 2022b).

Fig. 2.

Functional validation and simultaneous binding examination of four mAbs. A All the four expressed mAbs possessed the functional ability of neutralizing the Delta variant. Neutralization ratios were calculated based on luminescence units detected (mean ± SD, n = 2). Dose-response neutralization curves were fit to a four parameter logistic equation by nonlinear regression analysis. B The combination of these four mAbs could still broadly neutralize Omicron sublineages BA.1, BA.2, and BA.4/5. Neutralization ratios were calculated based on RLUs detected (mean ± SD, n = 2). Dose-response neutralization curves were fitted to a four parameter logistic equation by nonlinear regression analysis. C The mAbs 2G1, REGN-10987 and S2X259 inhibited the binding of biotin-labeled spike protein to coated hACE2-Fc protein in ELISA assay (mean ± SD, n = 2), whereas CV3-25 did not. Comparison was carried out by one-way ANOVA with Tukey post hoc correction for family-wise error rate. ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001. D Surface plasmon resonance analysis showed that these four mAbs could successively bind on spike protein. SD, standard deviation.

To examine if these four mAbs can simultaneously bind to the spike protein, we conducted a SPR assay. A recombinant prefusion-stablized spike ectodomain was covalently immobilized onto the chip and then solutions of each mAb in excessive amount were successively flowed through the chip. The increased mass on the chip contributed by mAbs binding was monitored. As the real-time monitoring chart showed, the mAbs 2G1, REGN-10987, S2X259, and CV3-25 were attached on the spike protein one after another, rendering the response unit detected stepwise ascendant (Fig. 2D). Thus we concluded that these four mAbs were able to simultaneously bind to the spike protein in a non-overlapping fashion.

3.3. Adaptability of replication-competent VSV-SARS-CoV-2-S virus to antibodies and their combinations

To further understand the viral adaptability to broad-spectrum antibodies and their combinations, firstly we assembled and recovered a SARS-CoV-2 spike-pseudotyped vesicular stomatitis virus with replication capability. The VSV antigenome was modified to substitute its native G glycoprotein with the wild-type S glycoprotein of SARS-CoV-2. This VSV antigenome also incorporates a GFP reporter gene for replication monitoring. The virus stock was titrated to be ∼ 2 × 106 PFU/mL. Then individual antibodies or combinations of two/three/four antibodies were serially diluted and incubated with VSV-SARS-CoV-2-S virus to neutralize susceptible variants, followed by applying to Vero E6 cells for infection. Three days later, the wells with suboptimal neutralizing concentration that permitted the virus to propagate were recorded, and the viral supernatants were harvested for the next passage (Fig. 3). Finally, a total of twenty passages were performed. The escaped viral population and the final viral population of passage number twenty (P20) without evasion were subjected to high-throughput RNA sequencing to interrogate the mutations accumulated in the viral population during 20 passages.

Fig. 3.

Schematic of viral adaptability assay with replication-competent VSV-SARS-CoV-2-S virus. Initially, viruses at an MOI of 0.01 were incubated with serial dilution of antibodies or their combinations, followed by applying to Vero E6 cells. After 72 h, 50 μL of viral supernatant from wells with suboptimal neutralizing concentration that permitted viral replication (> 20% GFP-positive cells) were passaged to fresh Vero E6 cells in the presence of serially diluted antibodies or their combinations, as previous step. A total of twenty passages were performed. Ab, antibody; conc, concentration; MOI, multiplicity of infection.

All the single broad-spectrum antibodies were escaped during viral passage (Fig. 4). Among them, the mAb S2X259 has a relatively good resistance and was escaped in P10 (or escaped in P7 for another independent experiment, as similar with the following P# in the bracket), while 2G1, REGN-10987 and CV3-25 were escaped in P3 (P3), P2 (P3) and P1 (P2), respectively (Fig. 4). The sequencing results revealed that mutations did happen in their critical epitope residues (F486I for 2G1, V445A for REGN-10987, G504D for S2X259 and S1161L for CV3-25) (Table 1, Supplementary Fig. S2A–D). To verify the effect of these identified mutations on the neutralizing ability of these antibodies, we generated lentiviral particles pseudotyped with spike carrying individual mutation. Expectedly, while the F486I mutation did abrogate the efficacy of 2G1, three other random mutations (N74K, F79L, and R685H) outside the epitope did not affect the neutralizing activity (Fig. 5). The pseudoviruses carrying the V445A, G504D, or S1161L mutations were also observed to totally resist the neutralization of mAb REGN-10987, S2X259, or CV3-25, respectively (Fig. 5). These observations showed that it is not difficult for SARS-CoV-2 spike to adapt to mutations that abolish broad-spectrum antibodies, even for broad sarbecovirus and broad betacoronavirus neutralizing antibodies.

Fig. 4.

The viral adaptability under selective pressures exerted by each single antibody alone. The suboptimal concentrations permitting viral replication in two independent experiments (n = 2) are shown as mean ± standard deviation.

Table 1.

High-throughput RNA sequencing revealed the mutations carried in the escaped viral populations of each single antibody.

| Viral population | Genome position | Nucleotide Ref. | Nucleotide Alt. | Protein position | Residue Ref. | Residue Alt. | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2G1a (P3)b | 222 | C | A | 74 | N | K | 100.00 |

| 235 | T | C | 79 | F | L | 100.00 | |

| 1119 | T | C | 373 | S | S | 99.96 | |

| 1456 | T | A | 486 | F | I | 99.94 | |

| 2054 | G | A | 685 | R | H | 100.00 | |

| REGN-10987 (P2) | 222 | C | A | 74 | N | K | 99.96 |

| 235 | T | C | 79 | F | L | 99.93 | |

| 1334 | T | C | 445 | V | A | 99.82 | |

| 2054 | G | A | 685 | R | H | 99.84 | |

| S2X259 (P10) | 222 | C | A | 74 | N | K | 100.00 |

| 235 | T | C | 79 | F | L | 100.00 | |

| 1105 | T | C | 369 | Y | H | 79.87 | |

| 1132 | A | G | 378 | K | E | 6.12 | |

| 1511 | G | A | 504 | G | D | 99.84 | |

| 2054 | G | A | 685 | R | H | 99.90 | |

| 2438 | C | T | 813 | S | L | 99.97 | |

| CV3-25 (P1) | 223 | G | A | 75 | G | R | 99.02 |

| 437 | A | G | 146 | H | R | 98.88 | |

| 2044 | A | G | 682 | R | G | 99.17 | |

| 2187 | G | A | 729 | V | V | 5.21 | |

| 3482 | C | T | 1161 | S | L | 98.84 |

Bold represents mutated residues that were located in the epitopes of corresponding mAbs and contributed to the viral resistance.

Ref., reference; Alt., altered.

The viral population under the long-term selective pressure of the monoclonal antibody.

The passage number subjected to sequencing.

Fig. 5.

The effect of individual mutations on the neutralizing activity of single or paired antibodies. Individual mutations identified in the escaped viral population were constructed based on wild-type spike protein sequence. Lentiviral particles pseudotyped with these mutated spikes were then used to test the neutralization of single or paired antibodies. Neutralization ratios were calculated based on RLUs detected (mean ± standard deviation, n = 3). Comparison was carried out by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett post hoc correction (two-tailed heteroscedastic unpaired t-test for comparison between S2X259/WT and S2X259/G504D). ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗∗P < 0.001.

As for the combinations of two antibodies, four of the six combinations were escaped during viral passage (Fig. 6). However, they were less susceptible to evasion than their individual treatment, with the observations that 2G1+CV3-25, REGN-10987+CV3-25, REGN-10987+S2X259 and S2X259+CV3-25 substantially delayed the emergence of escape variants until P15 (P15), P14 (P11), P16 (P14) and P12 (P17), respectively (Fig. 6). And the evasions required selection of multiple simultaneous mutations impacting each antibody (Table 2, Supplementary Fig. S2E–H). We also evaluated the impact of individual escape mutations on the neutralizing activity of paired antibodies using lentiviral pseudoviruses. The escape mutation of one component antibody could significantly or slightly impair the efficacy of paired antibodies, possibly depending on the potency of that component antibody (Fig. 5). Two combinations of two antibodies (2G1+ REGN-10987 and 2G1+S2X259) have not been escaped, albeit their efficacy was observed slightly dampened (Fig. 6). Mutational landscape showed V445I mutation that escapes REGN-10987 has emerged in the 2G1+ REGN-10987 combination, but its frequency was low (10.85%) (Table 2). And F486L mutation that can escape 2G1 was presented in the 2G1+S2X259 combination with 100% frequency (Table 2). Both these two combinations did not observe mutations that can escape another antibody component (Table 2).

Fig. 6.

The viral adaptability under selective pressures exerted by combinations of two antibodies. The suboptimal concentrations permitting viral replication in two independent experiments (n = 2) are shown as mean ± standard deviation. Comparisons between “two combos” and single antibody in Fig. 4 were carried out by two-way ANOVA statistical analysis with Tukey post hoc correction. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001. DF, degree of freedom.

Table 2.

High-throughput RNA sequencing revealed the mutations carried in the escaped viral populations or P20 viral populations of each “two combos”.

| Viral population | Genome position | Nucleotide Ref. | Nucleotide Alt. | Protein position | Residue Ref. | Residue Alt. | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2G1+REGN-10987 (P20) | 137 | G | A | 46 | S | N | 15.61 |

| 214 | G | A | 72 | G | R | 5.97 | |

| 222 | C | A | 74 | N | K | 100.00 | |

| 235 | T | C | 79 | F | L | 100.00 | |

| 1037 | G | A | 346 | R | H | 100.00 | |

| 1333 | G | A | 445 | V | I | 10.85 | |

| 1448 | T | C | 483 | V | A | 6.65 | |

| 2054 | G | A | 685 | R | H | 99.94 | |

| 2438 | C | T | 813 | S | L | 100.00 | |

| 2G1+S2X259 (P20) | 222 | C | A | 74 | N | K | 100.00 |

| 235 | T | C | 79 | F | L | 100.00 | |

| 1456 | T | C | 486 | F | L | 100.00 | |

| 1700 | G | A | 567 | R | K | 19.01 | |

| 2054 | G | A | 685 | R | H | 99.95 | |

| 2187 | G | A | 729 | V | V | 17.85 | |

| 2568 | T | C | 856 | N | N | 100.00 | |

| 2G1+CV3-25 (P15) | 222 | C | A | 74 | N | K | 100.00 |

| 235 | T | C | 79 | F | L | 100.00 | |

| 1456 | T | A | 486 | F | I | 100.00 | |

| 2054 | G | A | 685 | R | H | 99.89 | |

| 2423 | A | G | 808 | D | G | 5.19 | |

| 3482 | C | T | 1161 | S | L | 99.90 | |

| REGN-10987+S2X259 (P16) | 222 | C | A | 74 | N | K | 100.00 |

| 235 | T | C | 79 | F | L | 99.92 | |

| 1334 | T | C | 445 | V | A | 100.00 | |

| 1511 | G | A | 504 | G | D | 99.84 | |

| 2054 | G | A | 685 | R | H | 99.97 | |

| 2238 | C | T | 746 | S | S | 7.42 | |

| REGN-10987+CV3-25 (P14) | 222 | C | A | 74 | N | K | 100.00 |

| 235 | T | C | 79 | F | L | 100.00 | |

| 1331 | A | C | 444 | K | T | 100.00 | |

| 1383 | G | A | 461 | L | L | 17.63 | |

| 2054 | G | A | 685 | R | H | 99.92 | |

| 3482 | C | T | 1161 | S | L | 95.74 | |

| S2X259+CV3-25 (P12) | 222 | C | A | 74 | N | K | 100.00 |

| 235 | T | C | 79 | F | L | 99.97 | |

| 555 | C | A | 185 | N | K | 14.10 | |

| 1107 | C | T | 369 | Y | Y | 100.00 | |

| 1511 | G | A | 504 | G | D | 99.98 | |

| 2054 | G | A | 685 | R | H | 99.82 | |

| 2438 | C | T | 813 | S | L | 100.00 | |

| 3291 | T | C | 1097 | S | S | 5.21 | |

| 3470 | A | G | 1157 | K | R | 92.75 |

Bold represents mutated residues that were located in the epitopes of corresponding two combos and contributed to the viral resistance.

Ref., reference; Alt., altered.

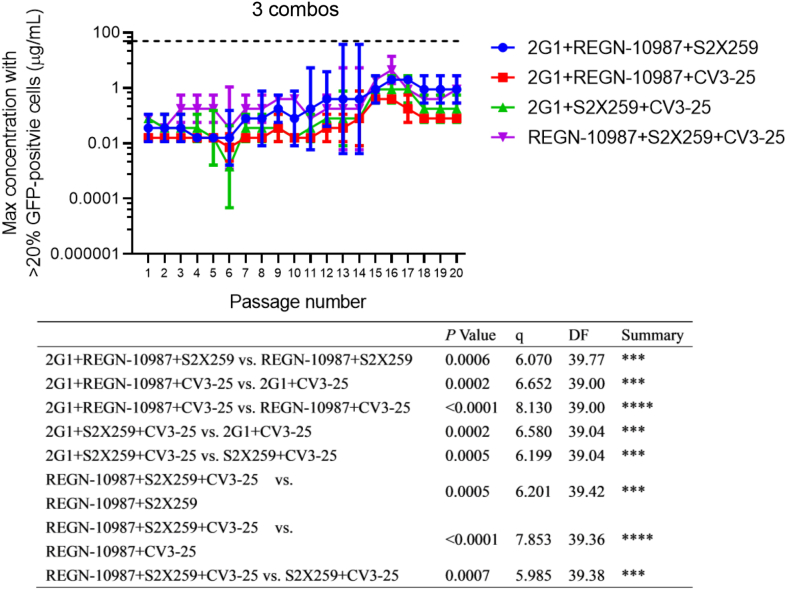

All the four combinations of three antibodies further enhanced the protection against viral escape, with no evasion observed through twenty consecutive passages. However, minor reduction in efficacy did happen (Fig. 7). Mutations G446S and T478K that affect REGN-10987 and 2G1 respectively, were emerged in the 2G1+REGN-10987+S2X259 combination (Table 3). In the 2G1+REGN-10987+CV3-25 combination, only the escape mutation (K444R) of REGN-10987 has occurred (Table 3). Similarly, only the mutation (T478A) that affects 2G1 neutralization was seen in the 2G1+S2X259+CV3-25 combination (Table 3). As for the REGN-10987+S2X259+CV3-25 combination, REGN-10987-resistant mutations (N440D and G446D) and S2X259-resistant mutation (G504D) were simultaneously emerged, but not the mutations escaping CV3-25 (Table 3).

Fig. 7.

The viral adaptability under selective pressures exerted by combinations of three antibodies. The suboptimal concentrations permitting viral replication in two independent experiments (n = 2) are shown as mean ± standard deviation. Comparisons between “three combos” and “two combos” in Fig. 6 were carried out by two-way ANOVA statistical analysis with Tukey post hoc correction. ∗∗∗P < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗P < 0.0001. DF, degree of freedom.

Table 3.

High-throughput RNA sequencing revealed the mutations carried in the P20 viral populations of each “three combos”.

| Viral population | Genome position | Nucleotide Ref. | Nucleotide Alt. | Protein position | Residue Ref. | Residue Alt. | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2G1+REGN-10987+S2X259 (P20) | 1212 | T | G | 404 | G | G | 100.00 |

| 1336 | G | A | 446 | G | S | 100.00 | |

| 1433 | C | A | 478 | T | K | 100.00 | |

| 2053 | C | A | 685 | R | S | 100.00 | |

| 2438 | C | T | 813 | S | L | 99.97 | |

| 3486 | C | A | 1162 | P | P | 100.00 | |

| 2G1+REGN-10987+CV3-25 (P20) | 190 | T | C | 64 | W | R | 10.34 |

| 1053 | C | T | 351 | Y | Y | 100.00 | |

| 1331 | A | G | 444 | K | R | 99.90 | |

| 1842 | C | T | 614 | D | D | 56.21 | |

| 2069 | A | G | 690 | Q | R | 11.99 | |

| 2438 | C | T | 813 | S | L | 100.00 | |

| 2736 | A | C | 912 | T | T | 62.41 | |

| 3612 | A | G | 1204 | G | G | 25.94 | |

| 2G1+S2X259+CV3-25 (P20) | 190 | T | A | 64 | W | R | 8.37 |

| 222 | C | A | 74 | N | K | 100.00 | |

| 235 | T | C | 79 | F | L | 100.00 | |

| 1432 | A | G | 478 | T | A | 100.00 | |

| 1451 | A | G | 484 | E | G | 100.00 | |

| 2054 | G | A | 685 | R | H | 99.89 | |

| 2085 | C | T | 695 | Y | Y | 100.00 | |

| 2326 | A | C | 776 | K | Q | 49.69 | |

| 2423 | A | G | 808 | D | G | 5.52 | |

| REGN-10987+S2X259+CV3-25 (P20) | 120 | C | T | 40 | D | D | 99.73 |

| 222 | C | A | 74 | N | K | 100.00 | |

| 235 | T | C | 79 | F | L | 100.00 | |

| 660 | C | T | 220 | F | F | 99.84 | |

| 1230 | A | C | 410 | I | I | 99.76 | |

| 1318 | A | G | 440 | N | D | 100.00 | |

| 1337 | G | A | 446 | G | D | 100.00 | |

| 1464 | C | T | 488 | C | C | 100.00 | |

| 1511 | G | A | 504 | G | D | 99.73 | |

| 2054 | G | A | 685 | R | H | 99.87 | |

| 2423 | A | G | 808 | D | G | 5.50 |

Bold represents mutated residues that were located in the epitopes of corresponding three combos.

Ref., reference; Alt., altered.

Encouragingly, the combination of these four antibodies not only survived throughout the twenty passages, but also sustained its optimal antiviral potency along (Fig. 8). Although multiple irrelevant random mutations occurred, no mutation capable of escaping any antibody component was observed (Table 4). Considering that the combinations of two/three/four antibodies did not show enhanced neutralizing potency as compared to individual antibodies (Supplementary Fig. S1), their better and better resistance might be merely contributed by the increasing number of combinational antibodies. Therefore, these results indicated that the number of combinational antibodies is a significant factor impacting the emergence of escape variants.

Fig. 8.

The viral adaptability under selective pressures exerted by combination of four antibodies. The suboptimal concentrations permitting viral replication in two independent experiments (n = 2) are shown as mean ± standard deviation.

Table 4.

High-throughput RNA sequencing revealed the mutations carried in the P20 viral populations of “four combos” as well as the reference viral populations.

| Viral population | Genome position | Nucleotide Ref. | Nucleotide Alt. | Protein position | Residue Ref. | Residue Alt. | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2G1+REGN-10987+S2X259+CV3-25 (P20) | 237 | T | G | 79 | F | L | 100.00 |

| 739 | A | C | 247 | S | R | 100.00 | |

| 897 | G | A | 299 | T | T | 100.00 | |

| 924 | T | C | 308 | V | V | 9.93 | |

| 1071 | C | T | 357 | R | R | 6.93 | |

| 1714 | A | C | 572 | T | P | 6.67 | |

| 1716 | A | C | 572 | T | T | 10.20 | |

| 2024 | A | G | 675 | Q | R | 72.11 | |

| 2053 | C | A | 685 | R | S | 100.00 | |

| 2423 | A | G | 808 | D | G | 9.95 | |

| 2927 | T | A | 976 | V | E | 10.17 | |

| 2945 | G | A | 982 | S | N | 99.76 | |

| 3627 | C | T | 1209 | Y | Y | 99.89 | |

| Inoculum (initial viral population) | 222 | C | A | 74 | N | K | 87.38 |

| 235 | T | C | 79 | F | L | 87.84 | |

| 2053 | C | A | 685 | R | S | 7.42 | |

| 2054 | G | A | 685 | R | H | 90.32 | |

| Isotype control antibody (P20) | 190 | T | C | 64 | W | R | 11.35 |

| 222 | C | A | 74 | N | K | 27.43 | |

| 235 | T | C | 79 | F | L | 29.05 | |

| 237 | T | G | 79 | F | L | 71.21 | |

| 739 | A | C | 247 | S | R | 76.98 | |

| 2053 | C | A | 685 | R | S | 74.39 | |

| 2054 | G | A | 685 | R | H | 25.00 | |

| 2372 | C | A | 791 | T | K | 5.78 | |

| 2945 | G | A | 982 | S | N | 75.56 | |

| Virus only (P20) | 222 | C | A | 74 | N | K | 61.25 |

| 235 | T | C | 79 | F | L | 63.24 | |

| 237 | T | G | 79 | F | L | 36.95 | |

| 739 | A | C | 247 | S | R | 52.82 | |

| 2053 | C | A | 685 | R | S | 43.85 | |

| 2054 | G | A | 685 | R | H | 55.01 | |

| 2423 | A | G | 808 | D | G | 5.19 | |

| 2438 | C | T | 813 | S | L | 38.57 | |

| 2945 | G | A | 982 | S | N | 46.13 |

Ref., reference; Alt., altered.

4. Discussion

The clinical observation, that vaccinated people were unable to completely repel the viral invasion but developed symptoms, suggests that the vaccine-induced humoral immunity was at a suboptimal concentration at the time of infection. It was possibly due to the decline of antibody level over time after vaccination (Sakharkar et al., 2021) or the paucity of broadly neutralizing antibodies against immune-evading variants (Yu et al., 2022). This suboptimal concentration of humoral immunity provides an opportunity for viral adaptation, just like the condition we created in the VSV-SARS-CoV-2-S virus assay for its optimal evolution, which may lead to the emergence of new variants. The constantly emerging variants have raised the need for seasonal updates of vaccine components. Although the emergence of new variant is inevitable and cannot be completely eliminated, it can be greatly delayed through rational vaccine design. In this study, we have demonstrated that the number of broadly neutralizing antibodies could be a significant factor, while the potency or breadth of antibodies might not.

In our study, although we previously obtained some broadly neutralizing antibodies from COVID-19 convalescent patients (Ma et al., 2022b), the epitopes of those broadly neutralizing antibodies (except 2G1) have not been clearly revealed by cryo-electron microscopy or X-ray crystallography. Therefore, in order to provide more precise guidance for rational vaccine design in research areas like reverse vaccinology, we selected four neutralizing antibodies whose binding structures were clearly resolved at the atomic level to perform the viral adaptability study. They target the conserved epitopes (RBM supersite, site II, and site IV) on RBD or the stem helix region. We have demonstrated that the combination of the antibodies can achieve an optimal effect of mitigating the emergence of escape variants. Further it may help to guide the rational antigen design of the future vaccines. The immunogens used in viral vector, protein subunit and mRNA vaccines are either spike protein- or RBD-based (Li M. et al., 2022). While the spike protein-based vaccines will elicit an immunodominant response to non-neutralizing epitopes on S2 and elsewhere on the spike (Amanat et al., 2021; Voss et al., 2021), the RBD-based vaccines may have a disadvantage, that is, they lack other immune epitopes on S protein and thus are vulnerable to antigenic drifts (Krammer, 2020). Our results provide a rationale for the design of RBD-stem helix tandem vaccine to precisely elicit as many broadly neutralizing antibodies as possible, so as to mitigate the generation of new variants in the vaccinated population. We anticipate that multivalent display of this RBD-stem helix tandem monomer can further improve the efficacy and breadth of the vaccine, by taking advantage of recent advances in nanoparticle vaccines (Kanekiyo et al., 2019; Walls et al., 2020b; Boyoglu-Barnum et al., 2021).

Common strategies to safeguard antiviral mAb therapeutics against treatment failure caused by escape variants involve selection of broadly neutralizing antibodies and/or design of antibody cocktails. Antibodies that target conserved epitopes have less probability of encountering escape mutations in circulating variants before their marketing. However, we found in this study that even the pan-sarbecovirus and pan-betacoronavirus neutralizing antibodies were relative easy to be escaped if the virus was under a strong treatment-exerting selective pressure. Previous studies showed that treatment with combining two antibodies that bind distinct and non-overlapping epitope can delay rapid mutational evasion seen with single antibody (Baum et al., 2020). This is presumably because escape would require the virus to simultaneously mutate at two distinct genetic positions, so as to abrogate neutralizing by both antibodies in the cocktail. Here we demonstrated that further increasing the number of antibodies in the combination will further mitigate the emergence of new variants. Therefore, for the future focus, the broadly neutralizing antibody therapeutics should focus on multi-antibodies cocktails to maintain coverage against emerging variants and prevent evasion.

Most neutralizing antibodies exert their activity through the mechanism of inhibiting ACE2 receptor binding. Receptor engagement is the first step in the viral infection process (Tortorici and Veesler, 2019). After that, S1 shedding and proteolytic cleavage of the S2 protein at the S2’ site are required to liberate the fusion peptide (Hoffmann et al., 2020). Then S2 is rearranged to embed the fusion peptide into the host membrane to form a fusion pore (Cai et al., 2020; Jackson et al., 2022). This rearrangement was interrupted by stem helix-targeted neutralizing antibodies (Li W. et al., 2022). Moreover, the amino acid sequence of stem helix is unchanged among the currently circulating Omicron sublineages (Supplementary Fig. S3). Herein we demonstrated that the combination of antibodies that adopt these two distinct neutralizing mechanisms can exert a synergistic effect to delay the generation of escape variants, which has not been reported previously.

The breadth of broadly neutralizing antibodies is due to their recognition of conserved epitopes in which mutations are rarely presented among viral variants. However, it is unclear that the absence of these mutations among variants was because either they were detrimental to viral fitness and failed to survive, or they have occurred but were in undetectable amount in viral population. In the VSV-SARS-CoV-2-S virus assay, we found these broadly neutralizing antibodies were not difficult to be escaped, and the resultant escape virus maintained its ability to replicate, suggesting their escape mutations are not detrimental to viral survival. Under a strong specific selective pressure, these escape mutations, which initially account for a tiny proportion, were rapidly selected out, thus capable of being detected by sequencing. The immunity elicited by infection or vaccination is polyclonal. As the number of combinational antibodies increases, the selective pressure they exert more and more resembles that of host immunity. We found that under the selective pressure of combinations of three/four antibodies, the highly conserved region among betacoronaviruses (stem-helix region) indeed remained “conserved”, as mutations in this region were not prone to be selected out and detected. This is consistent with the observations in the naturally evolving virus under the selective pressure of host immunity (Singer et al., 2020). These data suggested that, 1) a single conserved region-based vaccine or a single broadly neutralizing antibody may remain effective against the ongoing antigenic drifts rather than losing their efficacy against new variants, due to the weak selective pressure on conserved regions of circulating variants; 2) however, they are still in great risks of being abolished by escape variants that may have existed as undetectable viral population.

5. Conclusions

Previous clinical observations prompt that SARS-CoV-2 was highly able to adapt to environmental pressure (Rockett et al., 2022), and this observation greatly stimulated our passion to investigate the viral adaptability in the presence of broadly neutralizing antibodies and their combinations. To this end, we selected four broadly neutralizing antibodies targeting four distinct epitopes (RBM supersite, site IV, site II, and stem-helix region), including a pan-sarbecovirus neutralizing antibody that recognizes the site II epitope and a pan-betacoronavirus neutralizing antibody that binds to the S2 stem-helix region. These neutralizing antibodies did not compete with each other and can simultaneously bind on the spike protein, which indicates that they are promising to constitute effective combinations to mitigate viral evasion. Indeed, in the viral adaptability assay, although the broadly neutralizing antibodies, including pan-sarbecovirus and pan-betacoronavirus neutralizing antibodies, were relative easy to be escaped if applied alone, the combinations of two/three/four antibodies were more and more difficult to be escaped. This suggests that the number of combinational antibodies is a more significant factor than the breadth of antibodies to mitigate the emergence of treatment-induced escape variants. In addition, the synergistic prevention of viral evasion by RBD- and stem-helix-targeted neutralizing antibodies provided a rationale for the design of RBD-stem helix tandem vaccine to impede the generation of new variants. These founding will guide future vaccine and therapeutic development efforts to combat SARS-CoV-2 variants.

Data availability

High-throughput sequencing data of the viral populations in the viral adaptability assay are deposited on the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) database under the BioProject accession number PRJNA890417.

Ethics statement

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Author contributions

Haoneng Tang: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, formal analysis, visualization, writing-original draft preparation, writing-review & editing. Yong Ke: methodology, investigation. Yunji Liao: investigation. Yanlin Bian: resources. Yunsheng Yuan: resources. Ziqi Wang: resources. Li Yang: resources. Hang Ma: resources. Tao Sun: supervision. Baohong Zhang: supervision. Xiaoju Zhang: supervision. Mingyuan Wu: supervision. Jianwei Zhu: supervision, writing-review & editing, funding acquisition.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81773621, 82073751 to J.Z.), the National Science and Technology Major Project “Key New Drug Creation and Manufacturing Program” of China (No.2019ZX09732001-019 to J.Z.), the Key R&D Supporting Program (Special Support for Developing Medicine for Infectious Diseases) from the Administration of Chinese and Singapore Tianjin Eco-city to Jecho Biopharmaceuticals Ltd. Co., and the Shanghai Jiao Tong University “Crossing Medical and Engineering” grant (20X190020003 to J.Z.).

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.virs.2022.11.005.

Contributor Information

Baohong Zhang, Email: bhzhang@sjtu.edu.cn.

Xiaoju Zhang, Email: zhangxiaoju@zzu.edu.cn.

Mingyuan Wu, Email: wumingyuan@sjtu.edu.cn.

Jianwei Zhu, Email: jianweiz@sjtu.edu.cn.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

Supplementary Fig_S2.tif.

Supplementary Fig_S3.tif.

References

- Amanat F., Thapa M., Lei T., Ahmed S.M.S., Adelsberg D.C., Carreño J.M., Strohmeier S., Schmitz A.J., Zafar S., Zhou J.Q., Rijnink W., Alshammary H., Borcherding N., Reiche A.G., Srivastava K., Sordillo E.M., van Bakel H., Turner J.S., Bajic G., Simon V., Ellebedy A.H., Krammer F. Sars-cov-2 mrna vaccination induces functionally diverse antibodies to ntd, rbd, and s2. Cell. 2021;184:3936–3948.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baum A., Fulton B.O., Wloga E., Copin R., Pascal K.E., Russo V., Giordano S., Lanza K., Negron N., Ni M., Wei Y., Atwal G.S., Murphy A.J., Stahl N., Yancopoulos G.D., Kyratsous C.A. Antibody cocktail to sars-cov-2 spike protein prevents rapid mutational escape seen with individual antibodies. Science. 2020;369:1014–1018. doi: 10.1126/science.abd0831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyoglu-Barnum S., Ellis D., Gillespie R.A., Hutchinson G.B., Park Y.J., Moin S.M., Acton O.J., Ravichandran R., Murphy M., Pettie D., Matheson N., Carter L., Creanga A., Watson M.J., Kephart S., Ataca S., Vaile J.R., Ueda G., Crank M.C., Stewart L., Lee K.K., Guttman M., Baker D., Mascola J.R., Veesler D., Graham B.S., King N.P., Kanekiyo M. Quadrivalent influenza nanoparticle vaccines induce broad protection. Nature. 2021;592:623–628. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03365-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Y., Zhang J., Xiao T., Peng H., Sterling S.M., Walsh R.M., Jr., Rawson S., Rits-Volloch S., Chen B. Distinct conformational states of sars-cov-2 spike protein. Science. 2020;369:1586–1592. doi: 10.1126/science.abd4251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y., Wang J., Jian F., Xiao T., Song W., Yisimayi A., Huang W., Li Q., Wang P., An R., Wang J., Wang Y., Niu X., Yang S., Liang H., Sun H., Li T., Yu Y., Cui Q., Liu S., Yang X., Du S., Zhang Z., Hao X., Shao F., Jin R., Wang X., Xiao J., Wang Y., Xie X.S. Omicron escapes the majority of existing sars-cov-2 neutralizing antibodies. Nature. 2022;602:657–663. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-04385-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y., Yisimayi A., Jian F., Song W., Xiao T., Wang L., Du S., Wang J., Li Q., Chen X., Wang P., Zhang Z., Liu P., An R., Hao X., Wang Y., Wang J., Feng R., Sun H., Zhao L., Zhang W., Zhao D., Zheng J., Yu L., Li C., Zhang N., Wang R., Niu X., Yang S., Song X., Zheng L., Li Z., Gu Q., Shao F., Huang W., Jin R., Shen Z., Wang Y., Wang X., Xiao J., Xie X.S. Ba.2.12.1, ba.4 and ba.5 escape antibodies elicited by omicron infection. bioRxiv. 2022 doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-04980-y. 2022.2004.2030.489997. Preprint. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerutti G., Guo Y., Zhou T., Gorman J., Lee M., Rapp M., Reddem E.R., Yu J., Bahna F., Bimela J., Huang Y., Katsamba P.S., Liu L., Nair M.S., Rawi R., Olia A.S., Wang P., Zhang B., Chuang G.Y., Ho D.D., Sheng Z., Kwong P.D., Shapiro L. Potent sars-cov-2 neutralizing antibodies directed against spike n-terminal domain target a single supersite. Cell Host Microbe. 2021;29:819–833. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2021.03.005. e817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford K.H.D., Dingens A.S., Eguia R., Wolf C.R., Wilcox N., Logue J.K., Shuey K., Casto A.M., Fiala B., Wrenn S., Pettie D., King N.P., Greninger A.L., Chu H.Y., Bloom J.D. Dynamics of neutralizing antibody titers in the months after severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection. J. Infect. Dis. 2021;223:197–205. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiaa618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dieterle M.E., Haslwanter D., Bortz R.H., 3rd, Wirchnianski A.S., Lasso G., Vergnolle O., Abbasi S.A., Fels J.M., Laudermilch E., Florez C., Mengotto A., Kimmel D., Malonis R.J., Georgiev G., Quiroz J., Barnhill J., Pirofski L.A., Daily J.P., Dye J.M., Lai J.R., Herbert A.S., Chandran K., Jangra R.K. A replication-competent vesicular stomatitis virus for studies of sars-cov-2 spike-mediated cell entry and its inhibition. Cell Host Microbe. 2020;28:486–496.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2020.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen J., Baum A., Pascal K.E., Russo V., Giordano S., Wloga E., Fulton B.O., Yan Y., Koon K., Patel K., Chung K.M., Hermann A., Ullman E., Cruz J., Rafique A., Huang T., Fairhurst J., Libertiny C., Malbec M., Lee W.Y., Welsh R., Farr G., Pennington S., Deshpande D., Cheng J., Watty A., Bouffard P., Babb R., Levenkova N., Chen C., Zhang B., Romero Hernandez A., Saotome K., Zhou Y., Franklin M., Sivapalasingam S., Lye D.C., Weston S., Logue J., Haupt R., Frieman M., Chen G., Olson W., Murphy A.J., Stahl N., Yancopoulos G.D., Kyratsous C.A. Studies in humanized mice and convalescent humans yield a sars-cov-2 antibody cocktail. Science. 2020;369:1010–1014. doi: 10.1126/science.abd0827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann M., Kleine-Weber H., Schroeder S., Krüger N., Herrler T., Erichsen S., Schiergens T.S., Herrler G., Wu N.H., Nitsche A., Müller M.A., Drosten C., Pöhlmann S. Sars-cov-2 cell entry depends on ace2 and tmprss2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell. 2020;181:271–280.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson C.B., Farzan M., Chen B., Choe H. Mechanisms of sars-cov-2 entry into cells. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2022;23:3–20. doi: 10.1038/s41580-021-00418-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanekiyo M., Joyce M.G., Gillespie R.A., Gallagher J.R., Andrews S.F., Yassine H.M., Wheatley A.K., Fisher B.E., Ambrozak D.R., Creanga A., Leung K., Yang E.S., Boyoglu-Barnum S., Georgiev I.S., Tsybovsky Y., Prabhakaran M.S., Andersen H., Kong W.P., Baxa U., Zephir K.L., Ledgerwood J.E., Koup R.A., Kwong P.D., Harris A.K., McDermott A.B., Mascola J.R., Graham B.S. Mosaic nanoparticle display of diverse influenza virus hemagglutinins elicits broad b cell responses. Nat. Immunol. 2019;20:362–372. doi: 10.1038/s41590-018-0305-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krammer F. Sars-cov-2 vaccines in development. Nature. 2020;586:516–527. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2798-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M., Wang H., Tian L., Pang Z., Yang Q., Huang T., Fan J., Song L., Tong Y., Fan H. Covid-19 vaccine development: milestones, lessons and prospects. Signal Transduct. Targeted Ther. 2022;7:146. doi: 10.1038/s41392-022-00996-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li W., Chen Y., Prévost J., Ullah I., Lu M., Gong S.Y., Tauzin A., Gasser R., Vézina D., Anand S.P., Goyette G., Chaterjee D., Ding S., Tolbert W.D., Grunst M.W., Bo Y., Zhang S., Richard J., Zhou F., Huang R.K., Esser L., Zeher A., Côté M., Kumar P., Sodroski J., Xia D., Uchil P.D., Pazgier M., Finzi A., Mothes W. Structural basis and mode of action for two broadly neutralizing antibodies against sars-cov-2 emerging variants of concern. Cell Rep. 2022;38 doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2021.110210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Ma M.L., Lei Q., Wang F., Hong W., Lai D.Y., Hou H., Xu Z.W., Zhang B., Chen H., Yu C., Xue J.B., Zheng Y.X., Wang X.N., Jiang H.W., Zhang H.N., Qi H., Guo S.J., Zhang Y., Lin X., Yao Z., Wu J., Sheng H., Zhang Y., Wei H., Sun Z., Fan X., Tao S.C. Linear epitope landscape of the sars-cov-2 spike protein constructed from 1,051 covid-19 patients. Cell Rep. 2021;34 doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2021.108915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L., Iketani S., Guo Y., Chan J.F., Wang M., Liu L., Luo Y., Chu H., Huang Y., Nair M.S., Yu J., Chik K.K., Yuen T.T., Yoon C., To K.K., Chen H., Yin M.T., Sobieszczyk M.E., Huang Y., Wang H.H., Sheng Z., Yuen K.Y., Ho D.D. Striking antibody evasion manifested by the omicron variant of sars-cov-2. Nature. 2022;602:676–681. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-04388-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma H., Tseng C.-T.K., Zong H., Liao Y., Ke Y., Tang H., Wang L., Wang Z., He Y., Chang Y., Wang S., Drelich A., Hsu J., Tat V., Yuan Y., Wu M., Liu J., Yue Y., Xu W., Zhang X., Wang Z., Yang L., Chen H., Bian Y., Zhang B., Yin H., Chen Y., Zhang E., Zhang X., Gilly J., Sun T., Han L., Xie Y., Jiang H., Zhu J. Efficient neutralization of sars-cov-2 omicron and other vocs by a broad spectrum antibody 8g3. bioRxiv. 2022 2022.2002.2025.482049. Preprint. [Google Scholar]

- Ma H., Guo Y., Tang H., Tseng C.-T.K., Wang L., Zong H., Wang Z., He Y., Chang Y., Wang S., Huang H., Ke Y., Yuan Y., Wu M., Zhang Y., Drelich A., Kempaiah K.R., Peng B.-H., Wang A., Yang K., Yin H., Liu J., Yue Y., Xu W., Zhu S., Ji T., Zhang X., Wang Z., Li G., Liu G., Song J., Mu L., Xiang Z., Song Z., Chen H., Bian Y., Zhang B., Chen H., Zhang J., Liao Y., Zhang L., Yang L., Chen Y., Gilly J., Xiao X., Han L., Jiang H., Xie Y., Zhou Q., Zhu J. Broad ultra-potent neutralization of sars-cov-2 variants by monoclonal antibodies specific to the tip of rbd. Cell Discovery. 2022;8:16. doi: 10.1038/s41421-022-00381-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCallum M., De Marco A., Lempp F.A., Tortorici M.A., Pinto D., Walls A.C., Beltramello M., Chen A., Liu Z., Zatta F., Zepeda S., di Iulio J., Bowen J.E., Montiel-Ruiz M., Zhou J., Rosen L.E., Bianchi S., Guarino B., Fregni C.S., Abdelnabi R., Foo S.C., Rothlauf P.W., Bloyet L.M., Benigni F., Cameroni E., Neyts J., Riva A., Snell G., Telenti A., Whelan S.P.J., Virgin H.W., Corti D., Pizzuto M.S., Veesler D. N-terminal domain antigenic mapping reveals a site of vulnerability for sars-cov-2. Cell. 2021;184:2332–2347.e16. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.03.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettersen E.F., Goddard T.D., Huang C.C., Couch G.S., Greenblatt D.M., Meng E.C., Ferrin T.E. Ucsf chimera--a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 2004;25:1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piccoli L., Park Y.J., Tortorici M.A., Czudnochowski N., Walls A.C., Beltramello M., Silacci-Fregni C., Pinto D., Rosen L.E., Bowen J.E., Acton O.J., Jaconi S., Guarino B., Minola A., Zatta F., Sprugasci N., Bassi J., Peter A., De Marco A., Nix J.C., Mele F., Jovic S., Rodriguez B.F., Gupta S.V., Jin F., Piumatti G., Lo Presti G., Pellanda A.F., Biggiogero M., Tarkowski M., Pizzuto M.S., Cameroni E., Havenar-Daughton C., Smithey M., Hong D., Lepori V., Albanese E., Ceschi A., Bernasconi E., Elzi L., Ferrari P., Garzoni C., Riva A., Snell G., Sallusto F., Fink K., Virgin H.W., Lanzavecchia A., Corti D., Veesler D. Mapping neutralizing and immunodominant sites on the sars-cov-2 spike receptor-binding domain by structure-guided high-resolution serology. Cell. 2020;183:1024–1042.e21. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.09.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto D., Sauer M.M., Czudnochowski N., Low J.S., Tortorici M.A., Housley M.P., Noack J., Walls A.C., Bowen J.E., Guarino B., Rosen L.E., di Iulio J., Jerak J., Kaiser H., Islam S., Jaconi S., Sprugasci N., Culap K., Abdelnabi R., Foo C., Coelmont L., Bartha I., Bianchi S., Silacci-Fregni C., Bassi J., Marzi R., Vetti E., Cassotta A., Ceschi A., Ferrari P., Cippà P.E., Giannini O., Ceruti S., Garzoni C., Riva A., Benigni F., Cameroni E., Piccoli L., Pizzuto M.S., Smithey M., Hong D., Telenti A., Lempp F.A., Neyts J., Havenar-Daughton C., Lanzavecchia A., Sallusto F., Snell G., Virgin H.W., Beltramello M., Corti D., Veesler D. Broad betacoronavirus neutralization by a stem helix-specific human antibody. Science. 2021;373:1109–1116. doi: 10.1126/science.abj3321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Planas D., Saunders N., Maes P., Guivel-Benhassine F., Planchais C., Buchrieser J., Bolland W.H., Porrot F., Staropoli I., Lemoine F., Péré H., Veyer D., Puech J., Rodary J., Baele G., Dellicour S., Raymenants J., Gorissen S., Geenen C., Vanmechelen B., Wawina-Bokalanga T., Martí-Carreras J., Cuypers L., Sève A., Hocqueloux L., Prazuck T., Rey F.A., Simon-Loriere E., Bruel T., Mouquet H., André E., Schwartz O. Considerable escape of sars-cov-2 omicron to antibody neutralization. Nature. 2022;602:671–675. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-04389-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockett R., Basile K., Maddocks S., Fong W., Agius J.E., Johnson-Mackinnon J., Arnott A., Chandra S., Gall M., Draper J., Martinez E., Sim E.M., Lee C., Ngo C., Ramsperger M., Ginn A.N., Wang Q., Fennell M., Ko D., Lim H.L., Gilroy N., O'Sullivan M.V.N., Chen S.C., Kok J., Dwyer D.E., Sintchenko V. Resistance mutations in sars-cov-2 delta variant after sotrovimab use. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022;386:1477–1479. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2120219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakharkar M., Rappazzo C.G., Wieland-Alter W.F., Hsieh C.L., Wrapp D., Esterman E.S., Kaku C.I., Wec A.Z., Geoghegan J.C., McLellan J.S., Connor R.I., Wright P.F., Walker L.M. Prolonged evolution of the human b cell response to sars-cov-2 infection. Sci Immunol. 2021;6:1–14. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.abg6916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauer M.M., Tortorici M.A., Park Y.J., Walls A.C., Homad L., Acton O.J., Bowen J.E., Wang C., Xiong X., de van der Schueren W., Quispe J., Hoffstrom B.G., Bosch B.J., McGuire A.T., Veesler D. Structural basis for broad coronavirus neutralization. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2021;28:478–486. doi: 10.1038/s41594-021-00596-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah P., Canziani G.A., Carter E.P., Chaiken I. The case for s2: the potential benefits of the s2 subunit of the sars-cov-2 spike protein as an immunogen in fighting the covid-19 pandemic. Front. Immunol. 2021;12:637–651. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.637651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer J., Gifford R., Cotten M., Robertson D.L. Cov-glue: A Web Application for Tracking Sars-Cov-2 Genomic Variation. 2020. http://cov-glue.cvr.gla.ac.uk/#/home

- Starr T.N., Greaney A.J., Addetia A., Hannon W.W., Choudhary M.C., Dingens A.S., Li J.Z., Bloom J.D. Prospective mapping of viral mutations that escape antibodies used to treat covid-19. Science. 2021;371:850–854. doi: 10.1126/science.abf9302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang H., Ke Y., Wang L., Wu M., Sun T., Zhu J. Recombinant decoy exhibits broad protection against omicron and resistance potential to future variants. Pharmaceuticals. 2022;15:1–18. doi: 10.3390/ph15081002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao K., Tzou P.L., Nouhin J., Gupta R.K., de Oliveira T., Kosakovsky Pond S.L., Fera D., Shafer R.W. The biological and clinical significance of emerging sars-cov-2 variants. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2021;22:757–773. doi: 10.1038/s41576-021-00408-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tortorici M.A., Veesler D. Structural insights into coronavirus entry. Adv. Virus Res. 2019;105:93–116. doi: 10.1016/bs.aivir.2019.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tortorici M.A., Czudnochowski N., Starr T.N., Marzi R., Walls A.C., Zatta F., Bowen J.E., Jaconi S., Di Iulio J., Wang Z., De Marco A., Zepeda S.K., Pinto D., Liu Z., Beltramello M., Bartha I., Housley M.P., Lempp F.A., Rosen L.E., Dellota E., Jr., Kaiser H., Montiel-Ruiz M., Zhou J., Addetia A., Guarino B., Culap K., Sprugasci N., Saliba C., Vetti E., Giacchetto-Sasselli I., Fregni C.S., Abdelnabi R., Foo S.C., Havenar-Daughton C., Schmid M.A., Benigni F., Cameroni E., Neyts J., Telenti A., Virgin H.W., Whelan S.P.J., Snell G., Bloom J.D., Corti D., Veesler D., Pizzuto M.S. Broad sarbecovirus neutralization by a human monoclonal antibody. Nature. 2021;597:103–108. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03817-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullah I., Prévost J., Ladinsky M.S., Stone H., Lu M., Anand S.P., Beaudoin-Bussières G., Symmes K., Benlarbi M., Ding S., Gasser R., Fink C., Chen Y., Tauzin A., Goyette G., Bourassa C., Medjahed H., Mack M., Chung K., Wilen C.B., Dekaban G.A., Dikeakos J.D., Bruce E.A., Kaufmann D.E., Stamatatos L., McGuire A.T., Richard J., Pazgier M., Bjorkman P.J., Mothes W., Finzi A., Kumar P., Uchil P.D. Live imaging of sars-cov-2 infection in mice reveals that neutralizing antibodies require fc function for optimal efficacy. Immunity. 2021;54:2143–2158.e15. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2021.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viana R., Moyo S., Amoako D.G., Tegally H., Scheepers C., Althaus C.L., Anyaneji U.J., Bester P.A., Boni M.F., Chand M., Choga W.T., Colquhoun R., Davids M., Deforche K., Doolabh D., du Plessis L., Engelbrecht S., Everatt J., Giandhari J., Giovanetti M., Hardie D., Hill V., Hsiao N.Y., Iranzadeh A., Ismail A., Joseph C., Joseph R., Koopile L., Kosakovsky Pond S.L., Kraemer M.U.G., Kuate-Lere L., Laguda-Akingba O., Lesetedi-Mafoko O., Lessells R.J., Lockman S., Lucaci A.G., Maharaj A., Mahlangu B., Maponga T., Mahlakwane K., Makatini Z., Marais G., Maruapula D., Masupu K., Matshaba M., Mayaphi S., Mbhele N., Mbulawa M.B., Mendes A., Mlisana K., Mnguni A., Mohale T., Moir M., Moruisi K., Mosepele M., Motsatsi G., Motswaledi M.S., Mphoyakgosi T., Msomi N., Mwangi P.N., Naidoo Y., Ntuli N., Nyaga M., Olubayo L., Pillay S., Radibe B., Ramphal Y., Ramphal U., San J.E., Scott L., Shapiro R., Singh L., Smith-Lawrence P., Stevens W., Strydom A., Subramoney K., Tebeila N., Tshiabuila D., Tsui J., van Wyk S., Weaver S., Wibmer C.K., Wilkinson E., Wolter N., Zarebski A.E., Zuze B., Goedhals D., Preiser W., Treurnicht F., Venter M., Williamson C., Pybus O.G., Bhiman J., Glass A., Martin D.P., Rambaut A., Gaseitsiwe S., von Gottberg A., de Oliveira T. Rapid epidemic expansion of the sars-cov-2 omicron variant in southern africa. Nature. 2022;603:679–686. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-04411-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voss W.N., Hou Y.J., Johnson N.V., Delidakis G., Kim J.E., Javanmardi K., Horton A.P., Bartzoka F., Paresi C.J., Tanno Y., Chou C.W., Abbasi S.A., Pickens W., George K., Boutz D.R., Towers D.M., McDaniel J.R., Billick D., Goike J., Rowe L., Batra D., Pohl J., Lee J., Gangappa S., Sambhara S., Gadush M., Wang N., Person M.D., Iverson B.L., Gollihar J.D., Dye J.M., Herbert A.S., Finkelstein I.J., Baric R.S., McLellan J.S., Georgiou G., Lavinder J.J., Ippolito G.C. Prevalent, protective, and convergent igg recognition of sars-cov-2 non-rbd spike epitopes. Science. 2021;372:1108–1112. doi: 10.1126/science.abg5268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wall E.C., Wu M., Harvey R., Kelly G., Warchal S., Sawyer C., Daniels R., Hobson P., Hatipoglu E., Ngai Y., Hussain S., Nicod J., Goldstone R., Ambrose K., Hindmarsh S., Beale R., Riddell A., Gamblin S., Howell M., Kassiotis G., Libri V., Williams B., Swanton C., Gandhi S., Bauer D.L. Neutralising antibody activity against sars-cov-2 vocs b.1.617.2 and b.1.351 by bnt162b2 vaccination. Lancet. 2021;397:2331–2333. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01290-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walls A.C., Park Y.J., Tortorici M.A., Wall A., McGuire A.T., Veesler D. Structure, function, and antigenicity of the sars-cov-2 spike glycoprotein. Cell. 2020;181:281–292. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.058. e286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walls A.C., Fiala B., Schäfer A., Wrenn S., Pham M.N., Murphy M., Tse L.V., Shehata L., O'Connor M.A., Chen C., Navarro M.J., Miranda M.C., Pettie D., Ravichandran R., Kraft J.C., Ogohara C., Palser A., Chalk S., Lee E.C., Guerriero K., Kepl E., Chow C.M., Sydeman C., Hodge E.A., Brown B., Fuller J.T., Dinnon K.H., 3rd, Gralinski L.E., Leist S.R., Gully K.L., Lewis T.B., Guttman M., Chu H.Y., Lee K.K., Fuller D.H., Baric R.S., Kellam P., Carter L., Pepper M., Sheahan T.P., Veesler D., King N.P. Elicitation of potent neutralizing antibody responses by designed protein nanoparticle vaccines for sars-cov-2. Cell. 2020;183:1367–1382. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.10.043. e1317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Zhou T., Zhang Y., Yang E.S., Schramm C.A., Shi W., Pegu A., Oloniniyi O.K., Henry A.R., Darko S., Narpala S.R., Hatcher C., Martinez D.R., Tsybovsky Y., Phung E., Abiona O.M., Antia A., Cale E.M., Chang L.A., Choe M., Corbett K.S., Davis R.L., DiPiazza A.T., Gordon I.J., Hait S.H., Hermanus T., Kgagudi P., Laboune F., Leung K., Liu T., Mason R.D., Nazzari A.F., Novik L., O'Connell S., O'Dell S., Olia A.S., Schmidt S.D., Stephens T., Stringham C.D., Talana C.A., Teng I.T., Wagner D.A., Widge A.T., Zhang B., Roederer M., Ledgerwood J.E., Ruckwardt T.J., Gaudinski M.R., Moore P.L., Doria-Rose N.A., Baric R.S., Graham B.S., McDermott A.B., Douek D.C., Kwong P.D., Mascola J.R., Sullivan N.J., Misasi J. Ultrapotent antibodies against diverse and highly transmissible sars-cov-2 variants. Science. 2021;373:1–14. doi: 10.1126/science.abh1766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P., Nair M.S., Liu L., Iketani S., Luo Y., Guo Y., Wang M., Yu J., Zhang B., Kwong P.D., Graham B.S., Mascola J.R., Chang J.Y., Yin M.T., Sobieszczyk M., Kyratsous C.A., Shapiro L., Sheng Z., Huang Y., Ho D.D. Antibody resistance of sars-cov-2 variants b.1.351 and b.1.1.7. Nature. 2021;593:130–135. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03398-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whelan S.P., Ball L.A., Barr J.N., Wertz G.T. Efficient recovery of infectious vesicular stomatitis virus entirely from cdna clones. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1995;92:8388–8392. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.18.8388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo H., Park S.J., Choi Y.K., Park T., Tanveer M., Cao Y., Kern N.R., Lee J., Yeom M.S., Croll T.I., Seok C., Im W. Developing a fully glycosylated full-length sars-cov-2 spike protein model in a viral membrane. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2020;124:7128–7137. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.0c04553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu X., Wei D., Xu W., Liu C., Guo W., Li X., Tan W., Liu L., Zhang X., Qu J., Yang Z., Chen E. Neutralizing activity of bbibp-corv vaccine-elicited sera against beta, delta and other sars-cov-2 variants of concern. Nat. Commun. 2022;13:1788. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-29477-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou P., Yuan M., Song G., Beutler N., Shaabani N., Huang D., He W.T., Zhu X., Callaghan S., Yong P., Anzanello F., Peng L., Ricketts J., Parren M., Garcia E., Rawlings S.A., Smith D.M., Nemazee D., Teijaro J.R., Rogers T.F., Wilson I.A., Burton D.R., Andrabi R. A human antibody reveals a conserved site on beta-coronavirus spike proteins and confers protection against sars-cov-2 infection. Sci. Transl. Med. 2022;14 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abi9215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data