Abstract

Background

Due to advances in interventional cardiology in recent years, more and more patients are currently receiving cardiac devices, with a subsequent increase in the number of patients with device-associated endocarditis. Device-associated endocarditis is a life-threatening disease with special diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. Interventional devices for left atrial appendage (LAA) closure have been available for several years. However, there have been very few case reports of LAA closure device–associated endocarditis.

Case summary

An 83-year-old woman presented with fever and fatigue. She had a history of permanent atrial fibrillation and recurrent bleeding on oral anticoagulation. Consequently, the patient underwent interventional LAA closure ∼20 months earlier. Blood cultures grew Staphylococcus aureus. Transoesophageal echocardiography revealed an LAA closure device–associated mobile, echo-dense mass that was consistent with infectious vegetation in this clinical context. Intravenous antibiotic therapy was started, and our heart team recommended complete removal of the device, which the patient refused. The patient subsequently died as a result of progressive endocarditis and multiple pre-existing co-morbidities.

Discussion

Left atrial appendage occlusion device–associated endocarditis has rarely been reported. Due to the increase in LAA closure device implantation, device-associated endocarditis is expected to increase in the future. Transoesophageal echocardiography is required for correct diagnosis. Our case report suggests that an infection can occur long after implantation.

Keywords: Endocarditis, Left atrial appendage closure, Case report, Amplatzer

Learning points.

Infectious endocarditis of a left atrial appendage (LAA) closure device is very rare. Physicians should be aware of this condition even after the completed endothelialization of the device.

The physicians should be aware that a late infection as a result of the LAA closure device may occur, even years after device implantation.

It is difficult to distinguish between thrombus and vegetation. A further diagnostic inclusive positron emission tomography scan may be helpful.

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is one of the most common arrhythmias worldwide. Its prevalence increases with advanced age and higher rates of chronic heart diseases.1 To reduce stroke in patients with AF, anticoagulation is necessary and is the standard treatment. However, this is contraindicated in patients who are at high risk for bleeding.1 In this subset of patients, alternative therapies may be advisable.1 The primary site of thrombus formation in the vast majority of AF patients is the left atrial appendage (LAA),2 making occlusion of the LAA a treatment to consider.

The technique of percutaneous closure of LAA with either the Watchman (Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA, USA) or the Amplatzer device (Abbott, Minneapolis, MN, USA) has been increasingly used over the past several years.3 In general, intracardiac implantation of a foreign material carries the risk of infection (cardiac device–related infective endocarditis). Olsen et al.4 reported the lifetime risk of system infection in patients with a pacemaker (1.19%), implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (1.91%), cardiac resynchronization therapy (2.18%), and cardiac resynchronization therapy-defibrillator (3.35%). Little is known about the incidence of infections associated with an LAAO or the subsequent management. To date, five case reports have been communicated in the literature.5–9 We report an additional case of an 83-year-old woman with Amplatzer LAA closure device–associated endocarditis.

Timeline

| Relevant past medical history | |

|---|---|

| An 83-year-old woman was admitted to the hospital with fever (38.6°), chills, fatigue, and decreased vigilance. The patient had a history of arterial hypertension, pulmonary hypertension, severe tricuspid regurgitation, and permanent AF and received an LAA occluder (LAAO) (Amplatzer Amulet©) 20 months before admission for recurrent bleedings on anticoagulation | |

| Diagnostic testing | Interventions |

| − Elevated white blood cell count (12110/μL) and C-reactive protein levels (165 mg/L) | − Initially, empirical antibiotic therapy consisting of metronidazole and ceftriaxone for presumptive cholecystitis |

| − Abdominal sonography showed gallbladder wall thickening (>3 mm) without cholecystolithiasis. Abdominal computer tomography (CT) suggested mild cholecystitis | − The therapy was narrowed later to flucloxacillin (4×3 g daily) and rifampicin (900 mg i.v.) |

| − Blood cultures grew Staphylococcus aureus | |

| − The transoesophageal echocardiogram (TEE), which revealed a mobile vegetation (0.9×0.8 cm) located on the LAAO | |

Case report

An 83-year-old woman was admitted to the hospital with fever (38.6°), lasting for 2 days, accompanied by chills, fatigue, and decreased alertness. The patient did not take any medication or antibiotics before admission or undergo any invasive procedure with the potential for bacteraemia during the previous year. The patient had a history of arterial hypertension, pulmonary hypertension, severe tricuspid regurgitation, and permanent AF and had received an LAAO (Amplatzer amulet©) 20 months before admission for recurrent bleedings on different oral anticoagulants (vitamin K antagonists and apixaban). The LAAO implantation had been uneventful. The patient had been treated for three months with aspirin and clopidogrel. A routine TEE examination (Figure 1, Supplementary material online, Videos S1–S3) 3 months after implantation had confirmed the correct position of the device without leakage.

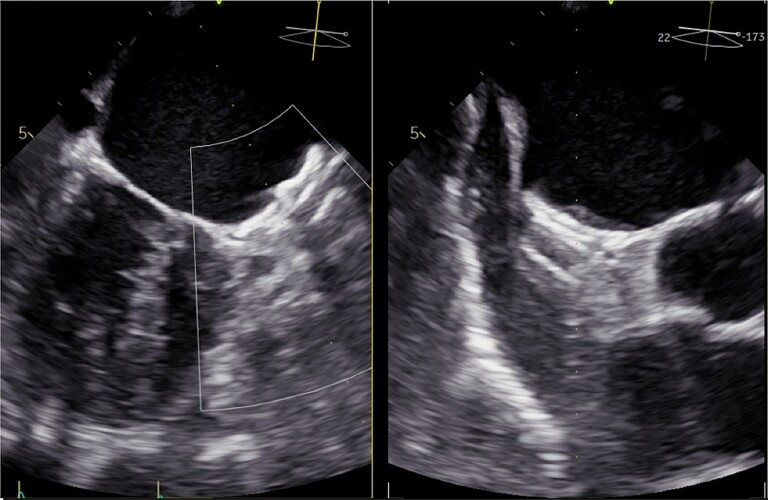

Figure 1.

Transesophageal echocardiography 3 months after implantation.

On admission, the initial work-up revealed an elevated white blood cell count (12110/μL), C-reactive protein level (165 mg/L), and procalcitonin level of 14.74 ng/mL (reference range < 0.5 ng/mL). Even though the patient did not have abdominal complaints, abdominal sonography was performed to exclude any intraabdominal focus. This revealed gall bladder wall thickening (> 3 mm) without cholecystolithiasis. An additional abdominal CT suggested mild cholecystitis.

Blood cultures were drawn, and an intravenous empirical antibiotic therapy consisting of metronidazole and ceftriaxone for presumptive cholecystitis was initiated.

On Day 2, blood cultures grew Staphylococcus aureus, and the antibiotics were narrowed to flucloxacillin (4×3 g i.v. daily) in combination with rifampicin (900 mg i.v.) based on susceptibility results. The patient underwent a TEE, which demonstrated a mobile and echo-dense mass (∼0.9×0.8 cm) located on the LAAO (Figure 2, Supplementary material online, Videos S4 and S5), which was consistent with vegetation in this clinical context. According to the modified Duke’s criteria,4 LAAO endocarditis was diagnosed.

Figure 2.

Transesophageal echocardiography shows veg.

The clinical condition of the patient improved. Her fever and white blood cell count normalized within 3 days, and the CRP and procalcitonin blood levels declined to 79 mg/L and 0.98 ng/mL, respectively—but did not normalize. Repeated sets of blood cultures obtained 5 days after initiating the antibiotics were negative.

The interdisciplinary endocarditis team was consulted. The team recommended an attempt to prove LAAO infection by using fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-positron emission tomography (PET)/CT imaging, followed up by cardiac surgery to remove the infected occluder, as otherwise medical treatment alone may not overcome this infection, exposing the patient to a high risk for arterial embolism.10,11 However, the patient did not give her consent to either the imaging technique or cardiac surgery.

The subsequent clinical course was dominated by her congestive heart failure and other pre-existing co-morbidities, without fever or sepsis under antibiotic therapy. The patient was referred to a palliative unit and died within 2 weeks with end-stage heart failure after diuretics were discontinued at the patient’s request. An autopsy was not performed.

Discussion

Cardiac device–related infectious endocarditis (IE) is a rare but serious complication.10,11 Despite the increased use of LAAOs, data about the incidence of LAAO-associated endocarditis are lacking.

We present a rare case of an infected Amplatzer LAAO 20 months after implantation despite complete endothelialization and adequate postprocedural antiplatelet therapy. The development of IE probably requires several independent events. An initial event is the adherence of microorganisms to pre-existing non-bacterial thrombotic material attached to the indwelling prosthetic devices/electrodes.12 Thus, any thrombotic material attached to (native valves or) intracardiac prosthetic material may be colonized by microorganisms at any time during transient bacteraemia. The incidence of device-related (non-infectious) thrombosis after LAAO implantation with Amplatzer Amulet varies in the literature between 4.413 and 16.7%.14 It has been suggested that thrombus formation after implantation of an LAAO is dependent on an incomplete sealing of the LAA ostium, as the thrombus is detected in the majority of cases between the Amulet disk and the uncovered portion of the limbus (secondary to suboptimal device sizing).13

Taken together, the presence of mobile masses attached to intracardiac prosthetic material is a prerequisite for the development of IE. The diagnosis of IE is usually based on clinical and laboratory signs for infection, positive blood cultures and echocardiographic imaging, and in selected cases, may require additional multimodality imaging such as soft tissue ultrasound, magnetic resonance imaging and PET scan,15 Particularly in case of cardiovascular implantable electronic device (CIED) infection, an F-FDG PET scan could provide helpful information. A meta-analysis by Juneau et al.15 showed high accuracy in the diagnosis of CIED infection with a sensitivity of 87% and a specificity of 95%. However, it remains uncertain whether this latter imaging modality could have demonstrated the small vegetation close to a metal-containing occluder in our case.

The diagnosis of IE in our case is also based on positive blood cultures with the detection of a typical germ, laboratory findings, and the echocardiographic detection of a mobile mass related to the LAAO, suggestive of vegetation within this context.

In our literature review, we searched the PubMed, Medline, Google Scholar, SCOPUS, and EMBASE databases up to January 2022 using the keywords infective endocarditis, left atrial appendage occluder, closure, Watchman occlusion device, and Amplatzer Amulet occluder to find published case reports with similar conditions. We were aware of only five cases of endocarditis related to LAA closure occlusion devices5–9 (Table 1).

Table 1.

List of the published cases of LAA-occulder endocarditis

| Khurmi et al.5 | Boukobza et al.6 | Jensen et al.7 | Madanat et al.8 | von Roeder et al.9 | This case | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 75 | 83 | 74 | 74 | 54 | 83 |

| Sex | Female | Male | Male | Male | Female | Female |

| Blood culture | S. aureus | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Enterobacter | S. aureus | S. aureus | S. aureus |

| LAA device | Watchman | Amplatzer Amulet | Watchman | Watchman | Amplatzer Amulet | Amplatzer Amulet |

| Time since implantation | 6 days | 30 months | 13 weeks | 12 months | 3 years | 20 months |

| Medication | Initially vancomycin and then switched to nafcillin | Cefotaxime + ciprofloxacin + amikacin | Not known | Initially vancomycin, then piperacillin-tazobactam, and then switched to cefazolin | Vancomycin | Initially metronidazole and ceftriaxone and then switched to flucloxacillin |

| Surgical removal | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Vegetation size | 5 mm | ‘Huge’ | 1.38×1.58 cm | 1.35×0.45 cm | Not known | 0.9×0.8 cm |

| Outcome | Discharged home | Died from refractory cardiogenic shock | Discharged home after a long postprocedural course | Discharged home | Discharged home | Died in the palliative unit |

| Embolization | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | No |

| Follow-up | Alive 6 months after discharge | — | Alive 10 months after discharge | Alive 6 months after discharge | No | — |

In general, the antimicrobial treatment of CIED infection should be individualized and based on the results of blood cultures. Because most CIED infections are due to staphylococcal species and, of those, up to 50% are methicillin-resistant, an empirical therapy of vancomycin should be initiated and continued until the results of cultures are known.4 In the case of definite CIED-related IE, medical therapy alone is frequently not sufficient and may be combined with complete removal of the device.4

It is interesting to note that the infectious process has been detected within the range of 6 days up to 36 months after LAAO implantation. Since we routinely check our patients for residual leakage 3 months after LAAO implantation, we could confirm, at least in our case, that there was no leakage, and the endothelialization process was presumably complete. We assume that, in our case, advanced heart failure with reduced cardiac output in combination with long-standing AF may have prompted the formation of LAAO thrombi and eventually endocarditis. The entry of S. aureus into the bloodstream remains obscure. In our case, we do not think that the mild cholecystitis was the entry since this process is usually associated with enteric pathogens other than S. aureus.

The management of LAAO endocarditis has not yet been defined. In four out of six cases, patients were referred to cardiac surgery for removal of the infected LAAO. However, a single case was presented, in which medical therapy alone was successful.8 Our patient responded initially to antibiotic therapy, too, and the infectious process appeared to be under control before the patient refused further treatment.

Physicians should be aware that a late infection of the LAAO may occur, even years after device implantation.16

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Hani Al-Terki, Cardiology and Rhythmology, University Hospital St Josef-Hospital Bochum, Ruhr University Bochum, Gudrunstraße 56, 44791 Bochum, Germany.

Andreas Mügge, Cardiology and Rhythmology, University Hospital St Josef-Hospital Bochum, Ruhr University Bochum, Gudrunstraße 56, 44791 Bochum, Germany.

Michael Gotzmann, Cardiology and Rhythmology, University Hospital St Josef-Hospital Bochum, Ruhr University Bochum, Gudrunstraße 56, 44791 Bochum, Germany.

Lead author biography

Hani Al-Terki is a consultant in ICU and cardiology in Bochum, Germany.

Hani Al-Terki is a consultant in ICU and cardiology in Bochum, Germany.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at European Heart Journal – Case Reports.

Slide sets: A fully edited slide set detailing this case and suitable for local presentation is available online as Supplementary data.

Consent: The patient reported in this case is deceased. Despite the best efforts of the authors, they have been unable to contact the patient's next-of-kin to obtain consent for publication. Every effort has been made to anonymize the case. This situation has been discussed with the editors.

Funding: None declared.

References

- 1. Fuster V, Ryden LE, Cannom DS, Crijns H, Curtis A, Ellenbogen K, Halperin JL, Kay GN, Le Huezey J-Y, Lowe JE, Olsson SB, Prystowsky EN, Tamargo JL, Wann LS. 2011 ACCF/AHA/HRS focused updates incorporated into the ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines developed in partnership with the European Society of Cardiology and in collaboration with the European Heart Rhythm Association and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;57:e101–e198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Blackshear JL, Odell JA. Appendage obliteration to reduce stroke in cardiac surgical patients with atrial fibrillation. Ann Thorac Surg 1996;61:755–759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Alfadhel M, Nestelberger T, McAlister C, Saw J. Left atrial appendage closure—current status and future directions. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 2021;69:101–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Olsen T, Jorgensen OD, Nielsen JC, Thogersen AM, Philbert BT, Johansen JB. Incidence of device-related infection in 97 750 patients: clinical data from the complete Danish device-cohort (1982–2018). Eur Heart J 2019;40:1862–1869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Khumri TM, Thibodeau JB, Main ML. Transesophageal echocardiographic diagnosis of left atrial appendage occluder device infection. Eur J Echocardiogr 2007;9:565–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Boukobza M, Smaali I, Duval X, Laissy JP. Convexity subarachnoid hemorrhage, Pseudomonas aeruginosa (PA) infective endocarditis and left atrial appendage occluder (LAAO) device infection. A case report. Open Neuroimag J 2017;11:26–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jensen J, Thaler C, Saxena R, Calcaterra D, Sanchez J, Orlandi Q, Harris KM. Transesophageal echocardiography to diagnose Watchman device infection. CASE (Phila) 2020;4:189–194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Madanat L, Bloomingdale R, Shah K, Khalife A, Haines D, Mehta N. Left atrial appendage occlusion device infection: take it or leave it? HeartRhythm 2021;7:750–753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. von Roeder M, Holzhey D, Sandri M, Thiele H. Simultaneous two-sided endocarditis: cardiac resynchronization leads and left atrial appendage occlude. EuroIntervention 2020;16:824–832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Habib G, Lancellotti P, Antunes MJ, Bongiorni MG, Casalta JP, Del Zotti F, Dulgheru R, Khoury GE, Erba PA, Iung B, Miro JM, Mulder BJ, Plonska-Gosciniak E, Price S, Roos-Hesselink J, Snygg-Martin U, Thuny F, Mas PT, Vilacosta I, Zamorano JL, ESC Scientific Document Group . 2015 ESC guidelines for the management of infective endocarditis: the Task Force for the Management of Infective Endocarditis of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) endorsed by: European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS), the European Association of Nuclear Medicine (EANM). Eur Heart J 2015;36:3075–3128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Baddour LM, Bettmann MA, Bolger AF, Epstein AE, Ferrieri P, Gerber MA, Gewitz MH, Jacobs AK, Levison ME, Newburger JW, Pallasch TJ, Wilson WR, Baltimore RS, Falace DA, Shulman ST, Tani LY, Taubert KA, AHA . Nonvalvular cardiovascular device-related infections. Circulation 2003;108:2015–2031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Holland T, Baddour L, Bayer A, Hoen B, Miro Jose M, Flowler VJR. Infective endocarditis. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2016;2:16059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tzikas A, Shakir S, Gafoor S, Omran H, Berti S, Santoro G, Kefer J, Landmesser U, Nielsen-Kudsk JE, Cruz-Gonzalez I, Sievert H, Tichelbäcker T, Kanagaratnam P, Nietlispach F, Aminian A, Kasch F, Freixa X, Danna P, Rezzaghi M, Vermeersch P, Stock F, Stolcova M, Costa M, Ibrahim R, Schillinger W, Meier B, Park J-W. Left atrial appendage occlusion for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation: multicenter experience with the Amplatzer cardiac plug. EuroIntervention 2016;11:1170–1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sedaghat A, Schrickel J, Andrié R, Schueler R, Nickenig G, Hammerstingl C. Thrombus formation after left atrial appendage occlusion with the Amplatzer Amulet device. J Am Coll Cardiol Electrophysiol 2017;3:71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Juneau D, Golfam M, Hazra S, Zuckier LS, Garas S, Redpath C, Bernick J, Leung E, Chih S, Wells G, Beanlands RS, Chow BJ. Positron emission tomography and single-photon emission computed tomography imaging in the diagnosis of cardiac implantable electronic device infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2017;10:e005772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Blomström-Lundqvist C, Traykov V, Erba PA, Burri H, Nielsen JC, Bongiorni MG, Poole J, Boriani G, Costa R, Deharo J-C, Epstein LM, Saghy L, Snygg-Martin U, Starck C, Tascini C, Strathmore N, ESC Scientific Document Group . European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) international consensus document on how to prevent, diagnose, and treat cardiac implantable electronic device infections-endorsed by the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS), the Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society (APHRS), the Latin American Heart Rhythm Society (LAHRS), International Society for Cardiovascular Infectious Diseases (ISCVID) and the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID) in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Europace 2020;4:515–549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.