Abstract

Background

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the major noncommunicable disease (NCD) accounting for 17.9 million deaths. If current trends continue, the annual number of deaths from CVD will rise to 22.2 million by 2030. The United Nations General Assembly adopted a sustainable development goal (SDG) by 2030 to reduce NCD mortality by one‐third. The purpose of this study was to analyze the CVD mortality trends in different countries implementing World Health Organization (WHO) NCD Action Plan and emphasize effective ways to achieve SDG.

Methods

WHO statistics, based on the Member‐States unified mortality and causes‐of‐death reports were used for analyzing trends and different interventions.

Results

Reduction of CVD mortality from 2000 to 2016 in 49 countries was achieved for stroke at 43% and ischemic heart disease at 30%. Smoking prevalence and raised blood pressure (RBP) decreased in 84% and 55% of the countries. Eighty‐nine percent of high‐income countries (HIC) demonstrated a decline in tobacco smoking against 67% in middle‐income countries (MIC). Sixty‐nine percent of HIC demonstrated a decline in RBP against 15% in MIC. CVD management, tobacco, and unhealthy diet reduction measures are significantly better in HIC. The air pollution level was higher in MIC.

Conclusion

Building partnerships between countries could enhance their efforts for CVD prevention and successful achievement of SDG.

Keywords: cardiovascular disease, life style, management, noncommunicable disease

Key point

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the major noncommunicable disease (NCD). Reduction of CVD mortality from 2000 to 2016 in 49 countries was achieved for stroke at 43% and ischemic heart disease at 30%. This decline is associated with decreasing prevalence of smoking and raised blood pressure. CVD management, tobacco, and unhealthy diet reduction measures are significantly better in high‐income countries. The air pollution level was higher in middle‐income countries. Building partnerships among countries with different economic development could enhance their efforts for CVD prevention and control to achieve the UN sustainable development goals by 2030 and reduce NCD mortality by one‐third.

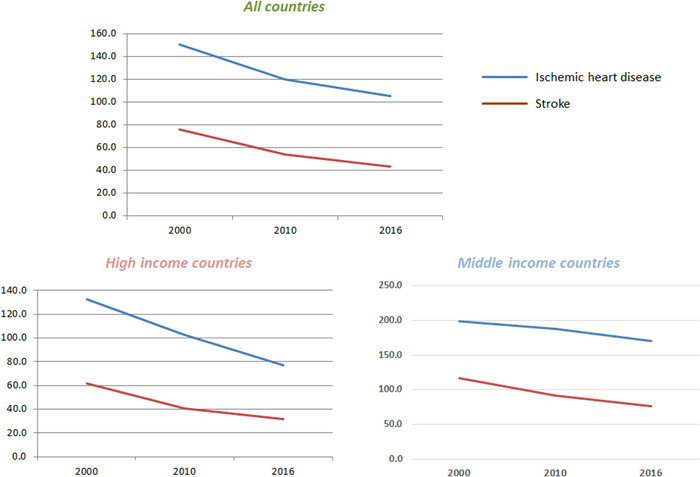

Age‐standardized cardiovascular disease mortality rate per 100,000 population in countries with different levels of socioeconomic development, both sexes, 2000–2016.

1. INTRODUCTION

Noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) are the leading causes of death worldwide. In 2016, they were responsible for 71% (41 million) of the 57 million deaths that occurred globally. Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the major NCD responsible for these deaths, accounting for 17.9 million cases or 44% of all NCD deaths and 31% of all global deaths. 1 An estimated 7.4 million of these deaths were due to ischemic heart disease (IHD), while 6.7 million were due to stroke. 2 One‐third of this mortality occurs in people under 70 years of age, 3 demonstrating that CVD is not solely a problem of the older population. A relationship is evident between premature CVD mortality and country income levels. CVD was common in high‐income countries (HIC) in the 1960s and 1970s, 4 but the age‐standardized mortality rate due to CVD has decreased since then through better preventive measures (such as lifestyle changes and risk factor control) and wider use of simple but effective treatments for acute events and secondary prevention. 5 By contrast, CVD was uncommon in low‐and middle‐income countries (LMIC) in the 1950s and 1960s, but the incidence increased substantially over the past three decades. Nowadays, more than 80% of the global burden of CVD occurs in these countries. 2 This high incidence is partly due to the large population, increased life expectancy, increased tobacco use, decreased physical activity, increased consumption of animal products, as well as increased obesity, leading to elevations in blood pressure, lipid abnormalities, and diabetes. If current trends continue, the annual number of deaths from CVD will rise to 22.2 million by 2030, 3 causing a lot of suffering for individuals and their families. They will also impose a substantial burden on society, particularly in LMIC, where the majority of CVD deaths occur, despite the fact that a large number of IHDs and strokes can be prevented by controlling major risk factors through lifestyle interventions and drug treatment when necessary. 3

The United Nations (UN) General Assembly has expressed a collective political will to control premature mortality from CVD and other NCDs. In September 2011, at the UN General Assembly in New York, a political declaration was adopted to strengthen national and international responses to prevent and control NCDs, 6 with World Health Organization (WHO) given a leadership role. The WHO Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of NCDs 2013–2020 7 was adopted by the World Health Assembly in 2013 8 and the 13th General Programme of Work 2019–2023 (GPW13) was accepted by the World Health Assembly in May 2018. 9 The Global Action Plan called for National Action Plans, which was instituted in every country to reduce the burden of NCDs, especially CVD, which is responsible for the majority of NCD deaths. GPW13 is aligned to the UN Agenda for sustainable development goals and targets (SDG), in particular target 3.4—“by 2030, reduce premature mortality from NCDs by one‐third through prevention and treatment, and promote mental health and well‐being.” 10

In 2017, WHO Director General announced the establishment of a WHO Independent High‐Level Commission on NCDs as a high‐level political tool to achieve SDG.

The first report published by the Commission in June 2018—“Time to Deliver” 11 —indicated a decline in CVD and chronic respiratory disease (CRD)‐related mortality. However, the global rate of decline in deaths from NCDs (CVD, CRD, cancer, and diabetes) by 17% from 2000 to 2015 is still not enough to meet the SDG target of 3.4 by 2030.

The purpose of this study was to analyze CVD mortality trends in countries with different socioeconomic statuses implementing the WHO Global Action Plan for the prevention and control of NCDs and emphasize the most effective ways to further decrease CVD and other major NCD mortalities based on the lessons learned to successfully achieve SDG 3.4 by 2030.

2. METHODS

2.1. Mortality trends

WHO statistics based on the unified mortality and causes‐of‐death reports of the Member‐State countries were used for analyzing global NCD mortality trends and making comparisons and assessments of different types of community‐based, country‐wide interventions. 12 Mortality trends from 2000 to the beginning of 2018 are based on the analysis of the latest available national information on mortality and its causes, submitted to WHO together with the latest available information from global WHO programs for causes of death of public health importance. The analysis includes estimates of age‐standardized death rates per 100,000 population by cause, sex, and age for the Member States. Only countries with multiple years of national death registration data and high completeness and quality of cause‐of‐death assignments were included in the analysis. Estimates for these countries may be compared, and a time series may be used for priority setting and policy evaluation. 12 The preparation of these statistics was undertaken by the WHO Department of Information, Evidence and Research in collaboration with WHO technical programs.

2.2. Lifestyle modifications

To address the growing burden of NCDs, the WHO identified a package of 16 lifestyles and NCD management “best buy” interventions that are cost‐effective, affordable, feasible, and scalable in all settings. 13 , 14 We compared the level of the lifestyle changes based on the WHO NCD Progress monitor in 2017. 15 We analyzed the lifestyle modification measures for the following factors: tobacco, alcohol, diet, and physical activity. The quantification of interventions is based on the level of the achievement of modification measures. We gave 2 points for fully achieved activities, 1 point for partially achieved, and no points for not achieved, no response, or “don't know.”

2.2.1. Measures to reduce tobacco usage

The following five demand‐reduction measures of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control 16 were implemented by member states 16 : (1) reduction of affordability by increasing excise taxes and prices of tobacco products; (2) elimination of exposure to second‐hand tobacco smoke in all indoor workplaces, public places, and public transport; (3) implementation of plain or standardized packaging or large graphic health warnings on all tobacco packages; (4) more actions and enforcement of comprehensive bans on tobacco advertising, promotion, and sponsorship; and (5) implementation of effective mass media campaigns that educate the public about the harms of smoking, tobacco use, and second‐hand smoke. A country can obtain a maximum of 10 points in case of full achievement of all five demand reduction measures.

2.2.2. Measures to reduce alcohol consumption

Member States have implemented, as appropriate according to national circumstances, the following three measures to reduce the use of alcohol as per the WHO Global Strategy to Reduce the Harmful Use of Alcohol 17 : (1) enaction and enforcement of restrictions on the physical availability of retailed alcohol (via reduced hours of sale); (2) enforcement of bans (across multiple types of media), or comprehensive restrictions; and (3) increasing excise taxes on alcoholic beverages. A country can obtain a maximum of 6 points in case of full achievement of all three demand reduction measures.

2.2.3. Measures to reduce unhealthy diet

Member States have implemented the following measures to reduce unhealthy diet 18 : (1) adoption of national policies to reduce common salt (sodium chloride) consumption, and (2) adoption of national policies that limit saturated fatty acids and virtually eliminate industrially produced trans‐fatty acids in the food supply. A country can obtain a maximum of 4 points in case of full achievement of both demand reduction measures

2.2.4. Public education and awareness campaigns on physical activity

Member States have implemented at least one recent national public awareness and motivational communication for physical activity, including mass media campaigns for physical activity behavioral change. 19 A country can obtain a maximum of 2 points in case of full achievement of this measure.

2.3. Management “best buy”

“Best buy” management and availability of essential medicines and basic technologies were assessed along with 10 essential NCD medicines: aspirins, angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors, statins, long‐acting calcium channel blockers, thiazide diuretics, beta‐blockers, metformin, insulin, bronchodilators, steroid inhalants, and six basic technologies: weighing scale, height measuring equipment, blood pressure measurement device, blood sugar and blood cholesterol monitoring devices with strips, and urine strips for albumin assay. 1 Eighty percent of the essential NCD medicines were relevant to the management of CVD and diabetes since CVD is the most common cause of death in diabetics. All basic technologies were relevant to CVD and diabetes diagnosis and treatment.

Countries reported the number of essential NCD medicines or essential NCD technologies as “generally available” for 10 out of 10 and 6 out of 6 instances, respectively. To further assess CVD management issues, Member States had been asked for counseling of eligible persons at high risk to prevent heart attacks, with emphasis on doing so at the primary health care (PHC) level. If the counseling had been provided, the country would report it as fully achieved, and if partially provided, it would be reported as partially achieved. Other categories of the level of achievements were the following: NA = not achieved, not applicable to country due to national situation; DK = country responded “don't know” to that question in the survey; and NR = no response to health facility counseling). We gave 2 points to countries that fully achieved counseling, 1 to those that partially achieved counseling, and 0 to others.

Separate questions concerning the proportions of PHC centers reported as offering CVD risk stratification 20 and having CVD guidelines that are utilized in at least 50% of health facilities were formulated. Risk stratification charts for PHC have been developed by WHO and the International Society of Hypertension. They provided the 10‐year risk of a fatal or nonfatal cardiovascular event by gender, age, systolic blood pressure, total blood cholesterol, smoking status, and the presence or absence of type 2 diabetes mellitus. In many LMIC settings, urine sugar may be used as a surrogate marker for diabetes. Since serum cholesterol assay was not available in a majority of the PHC settings, in this case, the average cholesterol levels derived from national surveys were used as the default value. A prediction chart helps to select those who will benefit most from treatment, as well as guide the intensity and nature of drug treatment. 21

2.4. Assessment of obesity, harmful use of alcohol, insufficient physical activity, and air pollution

Obesity and both indoor and outdoor air pollution are not on the “best buy” list. We analyzed these risk factors at the end of the observation period (2016), along with other risk factors.

Obesity in adults was defined as the percentage of the population aged 18 years and older having a body mass index ≥ 30 kg/m2 and in adolescents as the percentage of the population aged 10–19 years who were more than 2 SD above the median of the WHO growth reference for children and adolescents. 1 , 22

Air pollution was assessed as the exceedance of the WHO guideline level for the annual mean concentration of particles of ≤2.5 µm in diameter (PM2.5) in the air.

Household air pollution was assessed by the percentage of the population with primary reliance on polluting fuels and technologies. 1

Alcohol consumption was assessed as total alcohol per capita consumption in liters of pure alcohol. 1 , 17

Insufficient physical activity was assessed as the percentage of the population aged 18 years and older who were physically inactive, defined as not meeting the WHO recommendations on physical activity for health. 1 , 19

Raised blood glucose was defined as the percentage of the population aged 18 years and older who has a fasting plasma glucose of 7.0 mmol/L or higher, or a history of diagnosis with diabetes, or use of insulin or oral hypoglycemic drugs. 1

Raised blood pressure was defined as the percentage of the population aged ≥18 years having a systolic blood pressure of ≥140 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure of ≥90 mmHg. 1 Current tobacco smoking was defined as the percentage of the population aged ≥15 years who smoked any tobacco products. 1 , 16

Adult risk factor trends for 2000, 2005, 2010, and 2015 were registered for tobacco smoking, obesity, and raised blood pressure (RBP).

2.5. Mortality estimates

Total CVD (IHD and stroke) mortality from 2000 to 2016 was analyzed in 49 countries out of 183 with the interim analysis in 2010. Thirty‐six countries (Australia, Austria, Bahamas, Belgium, Brunei Darussalam, Canada, Chile, Croatia, Czechia, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxemburg, Malta, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Republic of Korea, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Trinidad and Tobago, United Kingdom, and the United States of America) belong to HIC according to the World Bank classification, and 13 countries (Armenia, Brazil, Cuba, Grenada, Guatemala, Kyrgyzstan, Mauritius, Mexico, Republic of Moldova, Romania, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, North Macedonia, and Uzbekistan) belong to middle‐income countries (MIC). 23

2.6. Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted in SPSS version 22.0 (SPSS Inc.). Continuous data, expressed as mean ± SD, were analyzed using Student's t test. A two‐sided p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Mortality dynamics

Baseline (year 2000) age‐standardized mortality rate for IHD was 150.4 ± 83.7 per 100,000 and 76.4 ± 45.6 for stroke. It gradually declined to 119.8 ± 86.7 and 105.7 ± 78.6 for IHD, and to 53.9 ± 36.6 and 43.7 ± 31.0 for stroke, respectively, in 2010 and 2016.

The decline is more visible in HIC 132.6 ± 60.9, 102.8 ± 60.0, 77.0 ± 46.4 for IHD, and 61.8 ± 31.6, 40.3 ± 21.7, 31.9 ± 18.1 for stroke than in MIC 199.1 ± 106.4, 187.9 ± 114.0, 170.7 ± 102.2 for IHD, and 61.8 ± 31.6, 40.3 ± 21.7, 31.9 ± 18.1 per 100,000 for stroke (Table 1 and Figure 1). On average, by the year 2016, IHD mortality declined by 29.7% and stroke mortality by 42.8% in 49 countries, 43.7% in HIC, and 15.3% in MIC.

Table 1.

Mean values of ischemic heart disease and stroke mortality in countries with different levels of socioeconomic development during 2000–2016

| Time | Ischemic heart disease | Stroke | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Time period (t) | Time period (t) | ||

| significance (p) | Mean ± SD | significance (p) | ||

| 2000 | 150.4 ± 83.7 | 2000–2010 | 76.4 ± 45.6 | 2000–2010 |

| t = 1.78, p > 0.05 | t = 2.7, p < 0.05 | |||

| 2010 | 119.8 ± 86.7 | 2010–2016 | 53.9 ± 36.6 | 2010–2016 |

| t = 0.84, p > 0.05 | t = 1.48, p > 0.05 | |||

| 2016 | 105.7 ± 78.6 | 2000–2016 | 43.7 ± 31.0 | 2000–2016 |

| t = 2.72, p < 0.01 | t = 4.15, p < 0.001 | |||

| High‐income countries, n = 36 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 132.6 ± 60.9 | 2000–2010 | 61.8 ± 31.6 | 2000–2010 |

| t = 2.09, p < 0.05 | t = 3.37, p < 0.001 | |||

| 2010 | 107.8 ± 60.0 | 2010–2016 | 40.3 ± 21.7 | 2010–2016 |

| t = 2.04, p < 0.05 | t = 1.76, p > 0.05 | |||

| 2016 | 77.0 ± 46.4 | 2000–2016 | 31.9 ± 18.1 | 2000–2016 |

| t = 4.37, p < 0.001 | t = 7.6, p < 0.001 | |||

| Middle‐income countries, n = 13 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 199.1 ± 106.4 | 2000–2010 | 116.9 ± 54.6 | 2000–2010 |

| t = 0.43, p > 0.05 | t = 1.32, p > 0.05 | |||

| 2010 | 187.9 ± 114.0 | 2010–2016 | 91.5 ± 43.5 | 2010–2016 |

| t = 0.67, p > 0.05 | t = 0.96, p > 0.05 | |||

| 2016 | 170.7 ± 102.2 | 2000–2016 | 76.5 ± 36.6 | 2000–2016 |

| t = 0.69, p > 0.05 | t = 2.23, p < 0.05 | |||

Figure 1.

Age‐standardized cardiovascular disease mortality rate per 100,000 population in countries with different levels of socioeconomic development, both sexes, 2000–2016.

These changes in mortality are associated with the long‐lasting global lifestyle modification campaigns like the tobacco‐free initiative, 16 as well as the globally coordinated approach to hypertension control initiated in 1999 24 along with CVD management “best buy” introduced in 2010. 14 The smoking prevalence from 2000 to 2015 decreased in 84% of the analyzed countries, did not change in 9% and increased only in 7% of countries. RBP for the same period decreased in 55%, did not change in 24%, and increased in 20% of the countries.

We have analyzed the dynamics of smoking and RBP prevalence in the population from 2000 to 2015 in HIC and MIC. Approximately 89% of HIC demonstrated a decline in tobacco smoking prevalence, while in MIC, only 67% demonstrated a decline. Regarding RBP, the values were more significant; 69% of HIC demonstrated a decline in RBP, while only 15% in MIC which were analyzed. Approximately 38% of MIC demonstrated no change in RBP prevalence, while 46% of countries demonstrated elevation of RBP prevalence compared with 19% and 11% for HIC. Obesity prevalence gradually increased in all countries.

To assess the status of CVD management, we checked the availability of essential medicines and basic technologies in HIC and MIC. Practically, in all HIC (besides Slovakia), 97% of all 10 essential drugs were available, while in MIC all these medicines were available only in 46% of countries. A similar difference was observed in the case of basic technologies, which are fully available in 89% of HIC, and only in 46% of MIC. To further assess the CVD management issues in countries with different socioeconomic statuses, the Member States have been asked for counseling for eligible persons at high risk to prevent heart attacks, with an emphasis on doing so at the primary care level. It has been done much better in HIC, with a big difference evident between the countries: 1.5 ± 0.9 in HIC and 0.2 ± 0.6 in MIC (t = 5.5, p < 0.001), or 78% in HIC and only 15% in MIC.

When we analyzed the availability of CVD management guidelines utilized in at least 50% of health facilities, 69% of MIC had guidelines; a similar figure was obtained for HIC (64%). However, only 11% of HIC had no guidelines against 31% in MIC. Approximately 25% of HIC had no information regarding this question.

Around 78% of HIC had more than 50% of PHC centers offering CVD risk stratification, while 6% of HIC had less than 25% of PHC centers offering stratification, and 16% of countries could not provide an answer to this question. Only 31% of MIC had more than 50% of health facilities offering CVD risk stratification, 8% had 25%–50% of PHC centers, and 38% had less than 25% of centers offering the stratification. Around 23% of MIC did not offer risk stratification at PHC.

3.2. Lifestyle modification efforts

We have noticed that after the UN NCD Declaration and WHO NCD action plan 2013–2020 global coordinated activities in the lifestyle modifications, the “best buy” has been implemented globally. CVD mortality trends continued to decline after 2010 and the implementation of the WHO “best buy.”

Implementation of the tobacco demand reduction measures was statistically significantly better in HIC than in MIC (p < 0.05), with the same concerns regarding unhealthy diet reduction measures. No difference was found between the groups in the implementation of harmful use of alcohol reduction measures and public education and awareness campaigns on physical activity. However, physical activity measures had a strong tendency to be better implemented in HIC (t = 1.6, 0.1 > p > 0.05) Table 2.

Table 2.

Lifestyle modification measures in countries with different socioeconomic development

| Lifestyle modifications | High‐income countries, Mean ± SD (n = 36) | Middle‐income countries, Mean ± SD (n = 13) | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tobacco demand reduction measures | 5.67 ± 1.91 | 3.84 ± 2.76 | 2.38 | <0.05 |

| Harmful use of alcohol reduction measures | 2.66 ± 1.21 | 2.46 ± 1.20 | >0.05 | |

| Unhealthy diet reduction measures | 2.70 ± 1.48 | 1.31 ± 1.65 | 2.72 | <0.01 |

| Public education and awareness campaigns on physical activity | 1.72 ± 0.70 | 1.23 ± 1.07 | 1.63 | >0.05 |

We found no significant difference between the groups in the level of NCD risk factors (Table 3) besides a higher level of ambient and household air pollution in MIC (p < 0.05). Obesity prevalence was higher in HIC (p < 0.05).

Table 3.

Mean population level of NCD risk factors in countries with different socioeconomic status

| Risk factors | High‐income countries (n = 36) | Middle‐income countries (n = 13) | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tobacco smoking, aged 15+ (%) | 23.2 ± 6.1 (n = 35) | 22.3 ± 8.0 (n = 9) | >0.05 | |

| Physical inactivity, aged 18+ (%) | 34.3 ± 6.5 (n = 34) | 28.1 ± 11.0 (n = 11) | 1.91 | >0.05 |

| Obesity (%) | 24.7 ± 6.5 | 20.9 ± 4.8 | 2.19 | <0.05 |

| Harmful use of alcohola | 10.0 ± 3.0 | 8.4 ± 3.5 | 1.48 | >0.05 |

| Raised blood pressure (%)b | 26.2 ± 6.6 | 25.1 ± 5.4 | >0.05 | |

| Ambient air pollutionc | 1.0 ± 0.8 | 2.8 ± 2.8 | 2.25 | <0.05 |

| Household air pollutiond | 5.2 ± 0.7 | 20.1 ± 21.8 | 2.46 | <0.05 |

| Salt (grams per day), aged 20+ | 9.6 ± 1.3 | 9.9 ± 2.8 | >0.05 | |

| Diabetes (raised blood glucose), adults aged 18+ (%) | 8.5 ± 1.8 | 9.6 ± 1.7 | 1.89 | >0.05 |

Note: Data are presented as mean ± SD.

Total alcohol per capita consumption in liters of pure alcohol per person (15 years+ over a calendar year adjusted for tourist consumption.

Percentage of the population aged 18 years and older having a systolic blood pressure ≥140 mm Hg and/or diastolic blood pressure ≥90mm Hg.

Exceedance of WHO guidelines level for an annual concentration of particles of ≤2.5 µm in the air (by a multiple of).

Household air pollution was assessed by the percentage of the population with primary reliance on polluting fuels and technologies.

Although we did not find a significant difference in the current prevalence of smoking between countries, a decline in the smoking prevalence trend from 2000 to 2015 was seen in 89% of HIC, and only in 67% of MIC.

4. DISCUSSION

The most visible decline in premature CVD mortality from 2000 to 2016 was achieved for stroke at 43%, while the 30% decline for IHD corresponds well with the UN SDG. A clear relationship is evident between premature CVD mortality and country income levels. The age‐standardized mortality rate was decreased in all countries, but a much more visible effect was seen in HIC. In HIC, the proportion of stroke deaths that were premature was almost half that of MIC (1.9 times HIC) in 2000 and more than half that of MIC (2.3 and 2.4 times HIC) in 2010 and 2016. In 2000, adults in MIC had 1.5 times higher IHD mortality than in HIC. In 2010, this difference increased to 1.8 times more than the previously reported, and in 2016 more than double the rate for adults with HIC (2.2 times).

This is the result of better organized secondary prevention and the effective use of simple, evidence‐based treatment for acute episodes. Better implementation of lifestyle modifications and “best buy” at the country level (tobacco control, unhealthy diet, and physical activity) also play an important role. There is still a potential for continuing use of these as evident in HIC strategies, for more widespread implementation to further reduce the rates of CVD. Along with tobacco cessation and healthy diet measures, which are being satisfactorily implemented, physical activity and harmful use of alcohol measures have great potential for better implementation. We found a significant difference in the level of air pollution both indoors and outdoors, which was higher in MIC. Air pollution is one of the leading risk factors for CVD and other major NCDs. 25 Both indoor and outdoor (ambient) air pollution is significantly higher in MIC according to our data. If in HIC, a lot of efforts were used to control the quality of air in LMIC, it still remains a big problem, especially for those most heavily exposed.

There are plenty of data concerning the effects of air pollution on human health, particularly focusing on PM2.5 as the primary pollutant of interest. Studies of the massive ambient air pollution impact in China before, during, and after extreme episodes, such as smog, for example, demonstrated a significant increase in CVD mortality. 26 A study involving 130 Chinese counties performed from 2013 to 2018 27 has shown additional cases of acute IHD associated with short‐term PM2.5 exposure. Long‐term effects of ambient PM2.5 pollution were estimated in the China‐PAR cohort study, wherein a 10‐μg/m3 increase in PM2.5 was correlated with new cases of hypertension. 28 Most air pollution is preventable. Government actions for air pollution control and clean air strategies led to a visible decline in air pollution and CVD morbidity and mortality in the United States, 29 Europe, 30 China, 31 and other countries and regions, 32 resulting in prompt and substantial health gains. 33

People spend most of their time indoors and in their homes. Solid fuel is often used in LMIC for cooking and heating, which are associated with a higher risk of cardiovascular and respiratory diseases, as well as all‐cause mortality. Reducing indoor air pollution is a priority for these countries. The risks can be lowered by switching to clean fuels and using better ventilation.

Household interventional studies in LMIC have involved “clean” cookstoves with improved combustion efficiency or ventilation, 34 replacement of wood or kerosene by less polluting fuels, such as ethanol or liquefied petroleum gas, and the use of household air filters that improve respiratory and nonrespiratory symptoms. In HIC, similar practices of fuel switching, stove technology upgrade, and use of household filters were employed. 35 , 36 , 37 Air pollution control measures have a great potential for the control of CVD and other major NCDs, as well as successful achievement of SDG by the year 2030. The growing prevalence of obesity shown in our study is a well‐known global phenomenon. Between 1980 and 2015, the worldwide prevalence of obesity increased twofold in 70 countries and gradually increased in many other countries. 38 Halting the rise in obesity is possible by establishing fiscal policies to reduce the consumption of sweetened beverages; improve the provision of healthy food in public institutions such as schools; implement public campaigns and social marketing initiatives on healthy dietary practice and physical activities; establish easy to understand nutrition labeling schemes on food products; develop guidelines, recommendations, and policy measures to reduce the content of free sugars and fat in food and beverages; reduce portion size; increase availability, affordability, and consumption of healthy foods, including fruits and vegetables; and restrict marketing of foods high in sugars, fat, and salt to children. 39

According to our data, people in HIC have a higher prevalence of obesity, but a better health care system and implementation of “best buys” could prevent the negative impact of obesity and overweight on CVD in HIC compared with MIC.

It is well‐known that many factors have delayed or even prevented the implementation of the experience learnt in HIC to LMIC. HIC, for instance, spent much more resources allocated on health for CVD prevention and management. Many LMIC still have a double burden of communicable diseases and NCDs, including poor nutrition and highly prevalent childhood diseases, which consume a substantial amount of health resources. These resources are mainly spent on providing curative, rather than preventive services. On the other hand, the high costs of curative services cannot be afforded by many individuals in LMIC. What can be done to contain the epidemic of CVD in LMIC? Building partnerships between HIC and LMIC for valuable exchange of knowledge and leverage of funds is vital and could enhance their preventive efforts. The WHO Global NCD Platform, which brings together the Global Coordination Mechanism on NCDs and the UN Interagency Task Force on the Prevention and Control of NCDs, gives a tangible perspective for this. 40 Based on the WHO's assessment that implementing all 16 “best buys” in all countries between 2018 and 2025 would avoid 9.6 million premature deaths, including CVD deaths, with huge economic return, the WHO NCD Platform analyses investments in four cost‐effective and proven policy package interventions: salt reduction, tobacco control, diet and physical activity awareness, as well as CVD and diabetes clinical interventions. Fourteen LMIC are participants in the study: Armenia, Bahrain, Barbados, Belarus, Cambodia, Ethiopia, Jamaica, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Mongolia, Turkey, Uzbekistan, Zambia, and the Philippines. Three of them are included in our analysis (Armenia, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan). A cost–benefit analysis compares these implementation costs with the estimated health gains and identifies which policy packages would give the greatest returns on investment. The return on investment is expected to exceed the required prevention and control costs.

These returns could be effectively used for strengthening health promotion and disease prevention activities in LMIC to decrease the current CVD mortality rate. This will also contribute to successful achievement of the UN SDG 3.4 in the area of NCDs by the year 2030, of which CVD has the highest contribution.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Dr. Khaltaev collected data, performed the statistical analysis, and prepared the manuscript. Dr. Akselrod collected the data and provided intellectual contribution as well as critical revision.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

No need.

Khaltaev N, Axelrod S. Countrywide cardiovascular disease prevention and control in 49 countries with different socio‐economic status. Chronic Dis Transl Med. 2022;8:296‐304. 10.1002/cdt3.34

Edited by Yi Cui

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data supporting the results can be obtained from the corresponding author.

REFERENCES

- 1. WHO . Noncommunicable Diseases Country Profiles. World Health Organization; 2018. Accessed October 10, 2020. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/274512

- 2. WHO . Global Status Report on Noncommunicable Diseases. World Health Organization; 2014. Accessed October 11, 2020. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/148114/1/9789241564854_eng.pdf

- 3. WHO . Hearts: Technical Package for Cardiovascular Disease Management in Primary Health Care. World Health Organization; 2016. Accessed October 11, 2020. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/252661

- 4. Dalen JE, Alpert JS, Goldberg RJ, Weinstein RS. The epidemic of the 20th century: coronary heart disease. Am J Med. 2014;127:807‐812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ford ES, Ajani UA, Croft JB, et al. Explaining the decrease in US deaths from coronary disease, 1980–2000. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2388‐2398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. United Nations . United Nations General Assembly Resolution A/RES/66/2. Political Declaration of the High‐level Meeting of the General Assembly on the Prevention and Control of Non‐communicable Diseases. United Nations; 2012. Accessed August 18, 2018. https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/720106/files/A_RES_66_2-EN.pdf

- 7. WHO . Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases 2013–2020. World Health Organization; 2013. Accessed August 16, 2018. https://www.who.int/nmh/events/ncd_action_plan/en/

- 8. WHO . Thirteenth General Programme of Work, 2019–2023. World Health Organization; 2018. Accessed August 16, 2018. https://www.who.int/about/what-we-do/gpw-thirteen-consultation/en/

- 9. WHO . World Health Assembly Resolution WHA71.1. Thirteenth General Programme of Work, 2019–2023. World Health Organization; 2018. Accessed August 16, 2018. https://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA71/A71_R1-en.pdf

- 10. United Nations . Transforming our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. United Nations; 2015. Accessed August 8, 2019. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/post2015/transformingourworld

- 11. World Health Organization . Time to Deliver: Report of the Who Independent High‐level Commission on Noncommunicable Diseases. World Health Organization; 2018. Accessed November 8, 2019. http://www.who.int/iris/handle/10665/272710. License: CC BY‐NC‐SA 3.0 IGO. [Google Scholar]

- 12. WHO . Global Health Estimates 2016: Deaths by Cause, Age, Sex, by Country and by Region, 2000–2016. World Health Organization; 2018. Accessed August 16, 2019. https://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/estimates/en/

- 13. WHO . Tackling NCDs “Best Buys” and other Recommended Interventions for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases. World Health Organization; 2017. Accessed August 16, 2018. https://www.who.int/ncds/management/best-buys/en/

- 14. World Health Organization . Global Status Report on Noncommunicable Diseases 2010. World Health Organization; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 15. World Health Organization . Noncommunicable Diseases Progress Monitor. World Health Organization; 2017.

- 16. WHO . WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (WHO FCTC). World Health Organization; 2003:42pp.

- 17. WHO . Global Strategy to Reduce the Harmful Use of Alcohol. World Health Organization; 2010:44pp. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18. WHO . Diet, Nutrition and the Prevention of Chronic Diseases. Report of a Joint WHO/FAO Expert Consultation. WHO Technical Report Series 916. World Health Organization; 2003. [PubMed]

- 19. WHO . Global Recommendations on Physical Activity for Health. World Health Organization; 2010. Accessed August 16, 2018. https://who.int/dietphysicalactivity/publications/9789241599979/en/ [PubMed]

- 20. WHO . Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease: Guidelines for Assessment and Management of Total Cardiovascular Risk. World Health Organization; 2007.

- 21. WHO . Package of Essential Noncommunicable (PEN) Disease Interventions for Primary Health Care in Low‐Resource Settings. World Health Organization; 2010. Accessed September 15, 2021. https://www/who.int/cardiovasculardiseases/publications/pen2010/en/

- 22. WHO . Obesity: Preventing and Managing the Global Epidemic. Report of a WHO Consultation. WHO Technical Report Series 894: World Health Organization; 2000. [PubMed]

- 23. New country classifications by income level : 2018–2019. Accessed January 18, 2020. https://blogs.worldbank.org. opendata.

- 24. 1999 World Health Organization‐International Society of Hypertension Guidelines for the Management of Hypertension . Guidelines Subcommittee. J Hypertens. 1999;17:151‐183. Accessed October 18, 2020. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10067786 [PubMed]

- 25. Schraufnagel DE, Balmes JR, Cowl CT, et al. Air pollution and noncommunicable diseases: a review by the Forum of International Respiratory Societies' Environmental Committee, part 1: the damaging effects of air pollution. Chest. 2019;155:409‐416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chen R, Yin P, Meng X, et al. Fine particulate air pollution and daily mortality. A nationwide analysis in 272 Chinese cities. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;196:73‐81. Accessed September 12, 2020. 10.1164/rccm.201609-1862OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chen C, Li T, Wang L, Qin J, Shi W. Short‐term exposure to fine particles and risk of cause‐specific mortality—China, 2013–2018. China CDC Weekly. 2019;1:8‐12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Huang K, Yang X, Liang F, et al. Long‐term exposure to fine particulate matter and hypertension incidence in China: the China‐PAR Cohort Study. Hypertension. 2019;73(6):1195‐1201.Accessed October 12, 2020. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.119.12666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Greenbaum DS. The Clean Air Act: substantial success and the challenges ahead. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2018;15:296‐297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Duan RR, Hao K, Yang T. Air pollution and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Chronic Dis Transl Med. 2020;6:260‐269. Accessed June 9, 2021. 10.1016/j.cdtm.2020.05.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tan X, Liu X, Shao H. Healthy China 2030: a vision for health care. Value in Health Regional Issues. 2017;12:112‐114. Accessed June 9, 2021. 10.1016/j.vhri.2017.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. World Health Organization . Ambient (Outdoor) Air Quality and Health. World Health Organization; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Schraufnagel DE, Balmes JR, De Matteis S, et al. Health benefits of air pollution reduction. Ann Am Thorac Soc . 2019:1478‐1487. Accessed June 10, 2021. 10.1513/AnnalsATS.-536CME201907, www.atsjournals.org [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34. Sood A, Assad NA, Barnes PJ, et al. ERS/ATS workshop report on respiratory health effects of household air pollution. Eur Respir J. 2018;51:1700698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Alexander D, Northcross A, Wilson N, et al. Randomized controlled ethanol cookstove intervention and blood pressure in pregnant Nigerian women. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195:1629‐1639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. McCracken JP, Smith KR, Dıaz A, Mittleman MA, Schwartz J. Chimney stove intervention to reduce long‐term wood smoke exposure lowers blood pressure among Guatemalan women. Environ Health Perspect. 2007;115:996‐1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Chuang HC, Ho KF, Lin LY, et al. Long‐term indoor air conditioner filtration and cardiovascular health: a randomized crossover intervention study. Environ Int. 2017;106:91‐96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bovet P, Chiolero A, Gedeon J. Health effects of overweight and obesity in 195 countries. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1495‐1496. Accessed August 18, 2018. 10.1056/NEJMc1710026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. WHO . Global Strategy on Diet, Physical Activity and Health. World Health Organization; 2006. Accessed August 22, 2020. https://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/en/

- 40. World Health Organization . Global Noncommunicable Diseases Platform. Accessed September 12, 2021. https://www.who.int/teams/global-noncommunicable-diseases-platform

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting the results can be obtained from the corresponding author.