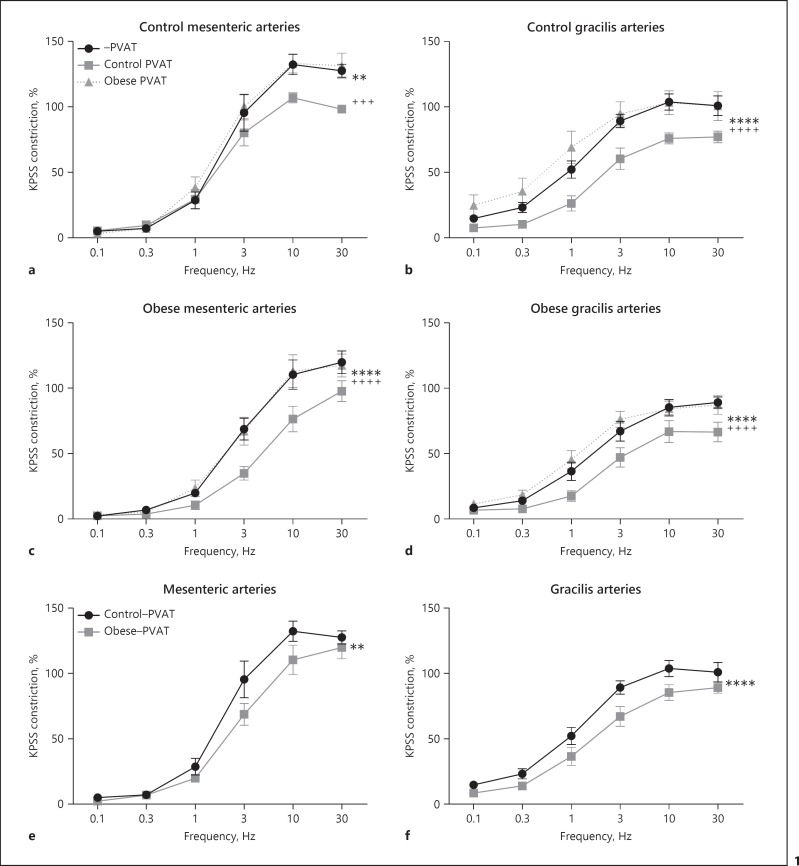

Fig. 1.

Loss of PVAT anticontractile function in obesity is due to dysfunctional PVAT. Mesenteric (a, c) and gracilis (b, d) resistance arteries were isolated from control (a, b) and obese mice (c, d). Arteries were subjected to EFS in the presence and absence of PVAT harvested from either control mice or obese mice, which was suspended above the artery in the organ bath (a −PVAT vs. control PVAT p < 0.01**, −PVAT vs. obese PVAT p > 0.05, control PVAT vs. obese PVAT p < 0.001+++. b −PVAT vs. control PVAT p < 0.0001****, −PVAT vs. obese PVAT p > 0.05, control PVAT vs. obese PVAT p < 0.0001++++. c −PVAT vs. control PVAT p < 0.0001****, −PVAT vs. obese PVAT p > 0.05, control PVAT vs. obese PVAT p < 0.000++++. d −PVAT vs. control PVAT p < 0.0001****, −PVAT vs. obese PVAT p > 0.05, control PVAT vs. obese PVAT p < 0.0001++++). The responses of −PVAT control and obese mesenteric arteries shown in (a, c) are compared in (e) (control −PVAT vs. obese −PVAT p < 0.01**). The responses of −PVAT control and obese gracilis arteries shown in (b, d) are compared in (f) (control −PVAT vs. obese −PVAT p < 0.0001****). Data shown are mean ± SEM (n = 7 all groups) (two-way ANOVAs with Bonferroni post hoc tests).