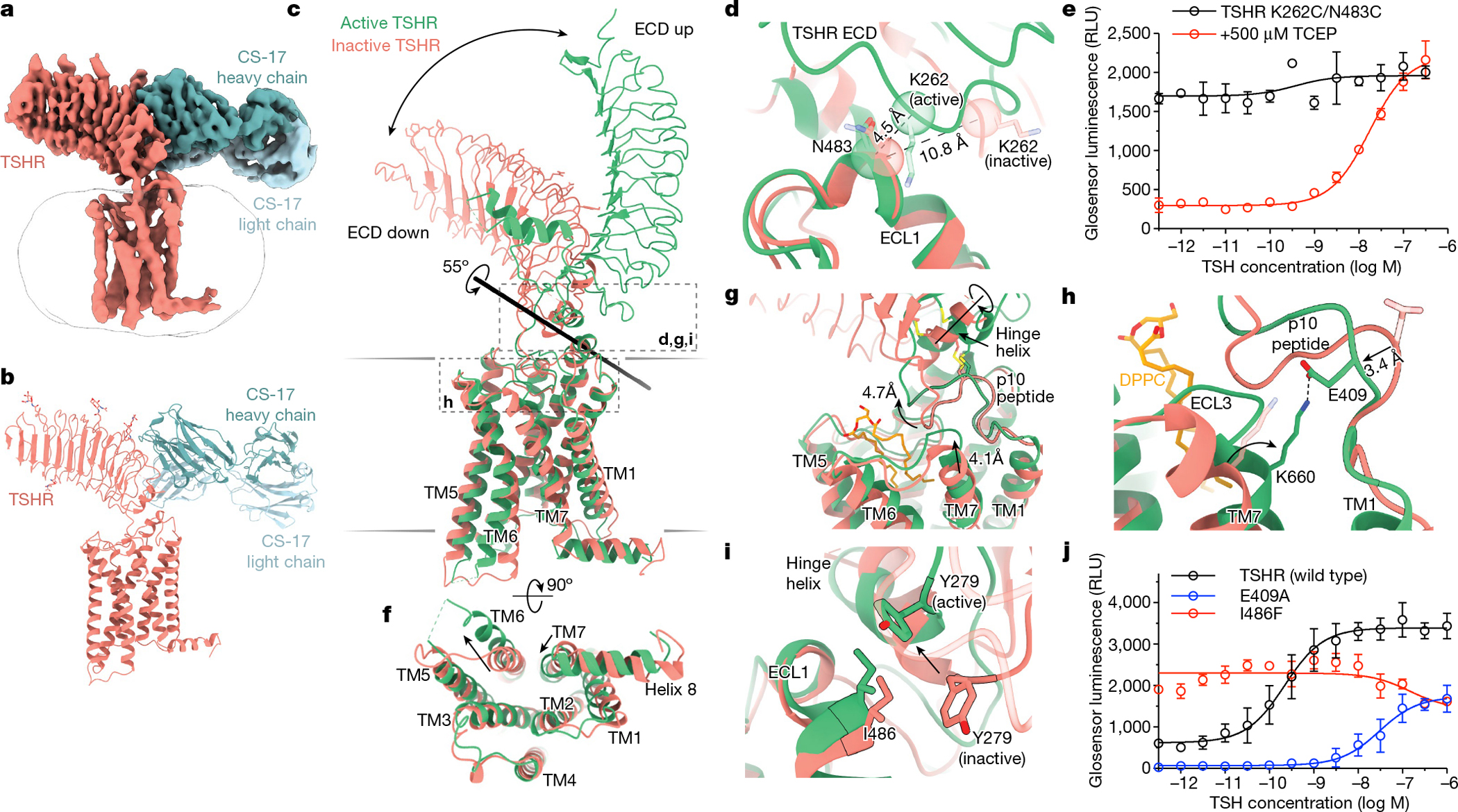

Fig. 2|. The activation mechanism of the TSHR revealed by the inactive structure bound to the inverse agonist CS-17.

a,b, Cryo-EM map (a) and model (b) of inactive TSHR bound to the CS-17 Fab. c, Structural comparison of inactive and active TSHR with the 7TM domain aligned. In inactive TSHR, the ECD is in a down orientation close to the membrane bilayer. In active TSHR, the ECD is in an up orientation. The ECD rotates 55° along an axis, as calculated by Dyndom3D55. d, Disulfide trapping of the active TSHR ECD conformation using a K262C/N483C mutant TSHR. The Cα distance between positions 262 and 483 (indicated in parentheses) would only enable a disulfide bond when the ECD is in the active, up conformation but not in the inactive, down conformation. e, The K262C/N483C TSHR mutant is more constitutively active than wild-type TSHR (see Extended Data Fig. 1). Addition of 500 μM TCEP reduces basal activity of the K262C/N483C disulfide-locked construct. f, In the active state, TM6 of TSHR moves outward by 14 Å, and TM7 moves inward by 4 Å. g, Upon activation, rotation of the ECD leads to a rotation of the hinge helix, an extracellular displacement of the p10 peptide and an inward movement of the extracellular tip of TM7. h, E409 in the p10 peptide interacts with K660 in TM7 in active TSHR. Inactive-state side chains (transparent) are not resolved but the peptide backbone suggests that the E409–K660 interaction is not maintained. i, Y279 traverses approximately 6 Å across the ECL1–hinge helix interface directly over I486. j, Disruption of p10–TM7 interactions (E409A) and perturbation of the ECL1–hinge helix interface (I486F) affect TSH-mediated receptor activation and basal activity, respectively. Data are mean ± s.d. of triplicate measurements from a representative experiment of n = 3 biological replicates.