Abstract

Background:

Mandibular distraction osteogenesis (MDO) is a kind of endogenous tissue engineering technology that lengthens the jaw and opens airway so that a patient can breathe safely and comfortably on his or her own. Endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) are crucial for MDO-related angiogenesis. Moreover, emerging evidence suggests that heat shock protein 20 (Hsp20) modulates angiogenesis under hypoxic conditions. However, the specific role of Hsp20 in EPCs, in the context of MDO, is not yet known. The aim of this study was to explore the expression of Hsp20 during MDO and the effects of Hsp20 on EPCs under hypoxia.

Methods:

Mandibular distraction osteogenesis and mandibular bone defect (MBD) canine model were established. The expression of CD34, CD133, HIF-1α, and Hsp20 in callus was detected by immunofluorescence on day 14 after surgery. Canine bone marrow EPCs were cultured, with or without optimal cobalt chloride (CoCl2) concentration. Hypoxic effects, caused by CoCl2, were evaluated by means of the cell cycle, cell apoptosis, transwell cell migration, and tube formation assays. The Hsp20/KDR/PI3K/Akt expression levels were evaluated via immunofluorescence, RT-qPCR, and western blot. Next, EPCs were incorporated with either Hsp20-overexpression or Hsp20-siRNA lentivirus. The resulting effects were evaluated as described above.

Results:

CD34, CD133, HIF-1α, and Hsp20 were displayed more positive in the callus of MDO compared with MBD. In addition, hypoxic conditions, generated by 0.1 mM CoCl2, in canine EPCs, accelerated cell proliferation, migration, tube formation, and Hsp20 expression. Hsp20 overexpression in EPCs significantly stimulated cell proliferation, migration, and tube formation, whereas Hsp20 inhibition produced the opposite effect. Additionally, the molecular mechanism was partly dependent on the KDR/PI3K/Akt pathway.

Conclusion:

In summary, herein, we present a novel mechanism of Hsp20-mediated regulation of canine EPCs via Akt activation in a hypoxic microenvironment.

Keywords: Endothelial progenitor cells, Heat shock protein 20, Angiogenesis, Hypoxia, PI3K/Akt pathway

Introduction

Mandibular distraction osteogenesis (MDO) is a kind of endogenous tissue engineering technology that lengthens the jaw and opens airway so that a patient can breathe safely and comfortably on his or her own. Since this technology was first applied by McCarthy et al. [1] in 1992, it was considered the most significant progress in oral and maxillofacial surgery. However, MDO also has multiple shortcomings, such as, a long consolidation period, which increases the risk of surgical complications or operational failures [2]. Therefore, it is critical to unveil the molecular mechanisms of angiogenesis and osteogenesis in the distraction gap to effectively shorten the consolidation time.

Callus remolding in the distraction gap is inseparable from angiogenesis and osteogenesis [3]. Angiogenesis plays an essential role in supplying adequate materials for osteogenic processes [4]. Endothelial progenitor cells, also known as EPCs, are the vascular endothelial progenitor cells, which were discovered by Asahara et al. [5] in 1997. These cells often mobilize from the bone marrow, travel through the peripheral blood to reach damaged area for vascular repair. Evidences suggest a large accumulation of EPCs occurs in the distraction gap during the consolidation period [6]. This suggests that EPCs play a critical role in MDO. However, at present, the exact process of EPC-mediated angiogenesis remains undetermined.

Several studies indicate that stem and progenitor cells have a physiological role in a hypoxic microenvironment, also known as a hypoxic niche [7]. In particular, Mantel CR et al. [8] demonstrated that the hematopoietic stem cells in the bone marrow reside in extremely hypoxic niches, where the average oxygen concentration is about 3% only. Moreover, bone marrow is a place where most EPCs live as well [9]. Interestingly, during the MDO-related distraction period, the callus becomes more hypoxic in response to mechanical strain [10], even more so than in inflammatory conditions [11]. Studies revealed that the hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha (HIF-1α) expression is much higher in the distraction gap than in normal bone tissues [12–14]. These results indicate that EPCs in the distraction gap also experience hypoxic conditions. Since EPCs are essential regulators of MDO-related angiogenesis, and hypoxia is an important driver of angiogenesis, there is much interest in the comprehension and manipulation of the association between EPCs and hypoxia.

Heat shock proteins (HSPs) are a large group of proteins that conservatively exist in many species from bacteria to mammals [15]. These proteins can temporarily be upregulated as a tool to maintain cellular homeostasis under numerous pathological states, such as, heat shock, ischemia, hypoxia, and oxidative stress [16, 17]. Until now, any information on the relationships between HSPs and EPCs is predominantly limited to Hsp27, Hsp32, and Hsp90 [18–20]. Nevertheless, it remains widely unknown whether Hsp20, another member of the HSPs family, holds a fundamental key in the regulation of EPC, which has a noticeable sequence homology with Hsp27.Heat shock protein 20 (Hsp20), also known as HSPB6, is a member of the small heat shock protein family that was first identified as a byproduct of HSPB1 and HSPB5 purification. Studies demonstrated that Hsp20 has comprehensive biological functions like cardioprotection [21, 22]. Hsp20 overexpression boosts cardiac function via angiogenesis and protects cardiomyocytes from oxidative stress by regulating kinase insert domain receptor (KDR). KDR, also known as vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR2), activates downstream signal pathways, such as, PI3K/Akt, which is a kind of tyrosine kinase receptor [23]. Protein kinase B, also known as Akt, plays a vital role in stem cell activities [24]. Activation of the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway promotes EPC proliferation and angiogenesis [25]. Apart from this, Hsp20 displays protective effects against oxidative stress in mesenchymal stem cells and cardiomyocytes via cell survival mechanism [21, 26]. Nevertheless, the roles of Hsp20 and PI3K/Akt signaling pathway in EPCs remain unclear. To further elucidate the underlying mechanism, EPCs were inoculated with either Hsp20-overexpression or Hsp20-siRNA lentivirus, and assessed for cell viability, proliferation, apoptosis, migration, tube formation, and expression of proteins belonging to the Akt signal pathway. Our results provide a favorable basis for future MDO therapy.

Materials and methods

Establishment of MDO and mandibular bone defect (MBD) models

The animals recruited in this study were 1-year-old male Beagle dogs purchased from the Experimental Animal Center of Guangxi Medical University (Nanning, China). The study protocol was approved by the Animal Care & Welfare Committee of Guangxi Medical University (IACUC no. SCXK GUI 2009–0002). The canine MDO/MBD models were fabricated as reported previously [27, 28]. Briefly, general anesthesia was induced in dogs with an intramuscular injection of xylazine hydrochloride (2 mg/kg) and an intraperitoneal injection of sodium pentobarbital (1 mg/kg). Skin over the right mandible was shaved and disinfected using 0.5% iodophor. A 5-cm incision was made, extending from the angulus oris to the masseter and parallel to the lower border of the mandible. The mandibular hypodermis and muscles were separated by blunt dissection. The facial artery was carefully preserved. Subsequently, the periosteum was dissected, and the body of the mandible was exposed. A vertical osteotomy was created between the 1st and 2nd molars using dental handpieces. The inferior alveolar neurovascular bundle was protected carefully during osteotomy. After completing the osteotomy, an internal distraction fixator (Cibei, Ningbo, China) was fixed to the osteotomy line following the principle of rigid internal fixation, and the incision was closed layer by layer. Finally, the dogs were intramuscularly injected with cefazolin sodium to prevent infection for 3 days postoperatively. The operating area was acutely lengthened to 7 mm for MBD and distraction was performed at a 1 mm/day rate for 7 days for MDO after a latency period of 7 days. After 14 days of surgery, the dogs were euthanized, and callus tissue was harvested.

Isolation and culture of EPCs

EPCs were isolated and identified according to our previous methods [10]. Briefly, bone marrow mononuclear cells were isolated from dog bone marrow using Ficoll density gradient centrifugation and Canine Bone Marrow Lymphocyte Separation Medium (Solarbio, Beijing, China). Next, 1 × 106 cells/cm2 were seeded onto Recombinant Human Fibronectin-coated T25 cell culture flasks (80 μl/cm2; LONZA, Basel, Switzerland) with 10% FBS EGM-2 medium (LONZA). The medium was first changed after 4 days to eliminate non-adherent cells. Then, the medium was changed again every 3 days to provide fresh nutrition. Thereafter, EPCs colonies were trypsinized and cultured on cell culture flasks or plates for further experimentation.

Characterization of EPCs

To identify EPCs, EPC morphology was observed and Dil-labeled acetylated low density lipoprotein (Dil-ac-LDL) uptake and FITC-labeled ulex europaeus agglutinin I (FITC-UEA-I) binding assay were employed. The adherent cells were incubated in 20 μg/ml Dil-ac-LDL (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA) at 37 °C for 4 h, then the cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde solution for 15 min. The fixed cells were then washed thrice in PBS and incubated in 10 μg/ml FITC-UEA-I (Invitrogen) at room temperature for 1 h. The nuclei were labeled with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) for 1 min. Subsequently, the cells were observed and images taken using an Axiophot Photomicroscope (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). Cells positive for both markers were identified as EPCs.

Cell viability assay

EPCs were seeded in each well of 96-well plates at a concentration of 5 × 103cells/ml in a final volume of 200 μl EGM-2 medium containing 0.5 mM CoCl2, 0.2 mM CoCl2, 0.1 mM CoCl2, or 0.0 mM CoCl2. After 24, 48, 72, or 96 h of incubation, 10 μl Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) solution (Dojindo, Kumamoto, Japan) was added to each well and incubated for 4 h at 37 °C. The OD values were then evaluated at 450 nm using a microplate reader (TECAN, Männedorf, Switzerland). All experiments were done in triplicates.

Lentiviral transduction

Primary EPCs were incubated with Hsp20-overexpression (Hsp20-OE), negative control (Hsp20-NC), Hsp20-siRNA (Hsp20-I), or scramble-siRNA (Hsp20-SC) lentivirus (Genechem, Shanghai, China) for 3 days and a 50 MOI value was used to identify optimal doses for these lentiviruses, according to the manufacturer’s protocols. Subsequently, lentivirus-transduced EPCs were selected with 0.5 μg/ml puromycin for subsequent assays. The sequence of Hsp20-overexpression (XM_541688.6) was obtained from GenBank (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA), and negative control was blank lentivirus. The sequence of Hsp20-siRNA was as follows: 5’-CCCTCAAGTCTCCAACCAT-3’, and the scramble-siRNA was 5’-TTCTCCGAACGTGTCACGT-3’.

Cell cycle analysis

EPCs from P2 at a confluency of 80–90% were trypsinized, then washed with PBS, and resuspended in 70% ethanol at 4 °C for 1 day. Thereafter, cells were washed again with PBS and stained with 1 ml Propidium Iodide/RNase staining solution (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA) in the dark at 37 °C for 30 min. The DNA content was calculated using a flow cytometer (CytoFLEX LX system, Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA ) at 488 nm and the percentage of cells at different phases of cell cycle was evaluated. The resulting data was analyzed using the ModFit LT™ 3.1 software (Verity Software House, Topsham, ME, USA). Each sample produced at least 100,000 events.

Cell apoptosis analysis

Annexin V-FITC/PI double staining assay was performed using the Annexin V-FITC/PI Apoptosis Kit (Solarbio, Beijing, China), according to the manufacturer’s protocols. Briefly, EPCs were trypsinized and resuspended in 1 ml Binding Buffer, then 5 μl Annexin V-FITC was introduced, followed by a 10 min incubation at room temperature in the dark. Next, 5 μl PI was introduced to the solution and incubated for 5 min at room temperature in the dark. The samples were immediately evaluated using a flow cytometer. Each sample also acquired at least 100,000 events.

Transwell migration assay

Transwell migration assays were performed using 6.5 mm Transwell® with 8.0 µm Pore Polycarbonate Membrane Insert, Sterile (Corning, NY, USA) to test the migration ability of EPCs. EPCs were seeded at 2 × 104 cells per well density into serum-free EGM-2 in the upper chamber of 24-well plates and allowed to migrate for 48 h toward EGM-2 containing 10% FBS in the lower chamber. After 48 h, the residual cells in the upper chamber were removed with cotton swabs and the migration cells in the under-surface of the polycarbonate membrane were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde solution for 20 min, prior to staining with 0.5% crystal violet solution for 30 min. Images were taken with a brightfield microscope at 200 × magnification. Migratory cells were counted by an experimenter blinded to the experimental conditions, who analyzed three random fields using the ImageJ 1.53d software (National Institutes of Health).

Tube formation assay

10 μl cold Matrigel Matri x (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) per well was added to μ-slide Angiogenesis plates (ibidi GmbH, BY, Germany). Meanwhile, 1 μl Calcein AM (Invitrogen) was added to 105 cells suspension for 15 min at 37 °C in the dark. After 30 min of incubation at 37 °C, 104 cells stained with Calcein AM were seeded onto plates with EGM-2 media. 6 h later, images were captured using a fluorescence microscope at 100 × magnification. To count the numbers of branches corresponding to the degree of in vitro angiogenesis, three random fields were analyzed by an experimenter blinded to the experimental conditions using the ImageJ 1.53d software (National Institutes of Health).

Immunofluorescence and histology assay

For callus tissue, samples were fixed by 4% paraformaldehyde for 3 days, decalcified in 10% EDTA solution for 8 weeks, then embedded in paraffin. 4 μm sections were producted using a rotary microtome (RM2255, Leica, Wetzlar, Germany). For EPCs, cells were seeded at 5 × 103cells per well in 96-well plates. After culturing for 48 h, cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min, prior to wash three times with PBS. Samples were perforated with 0.5% Triton™ X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) for 30 min, then blocked in 5% goat serum for 30 min after washed thrice with PBS, and overnight incubated in anti-CD34 (12-0340-42, 1:100, Invitrogen), anti-CD133 (12-1331-82, 1:100, Invitrogen), anti-Hsp20 (ab13491; 1:1000, Abcam, Cambridge, UK) and anti-HIF-1α (1:100, MA1-1651B, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) at 4 °C. After rinsing thrice with PBS, samples were incubated with Goat anti-Rabbit IgG (H + L) Cross-Adsorbed Secondary Antibodies (Alexa Fluor 594, 1:1000, Invitrogen), Goat anti-Rabbit IgG (H + L) Highly Cross-Adsorbed Secondary Antibody (Alexa Fluor 488, 1:1000, Invitrogen) and Goat anti-Mouse IgG (H + L) Highly Cross-Adsorbed Secondary Antibody (Alexa Fluor 488, 1:1000, Invitrogen) for 1 h at room temperature in the dark. Nuclei were labeled with DAPI before sample photos were captured using a Zeiss axiophot photomicroscope. Normalized mean fluorescence intensity (NMFI) was calculated from three random fields by an experimenter blinded to the experimental conditions, and using the ImageJ 1.53d software (National Institutes of Health) instructed by a previous method [29]. In addition, sections were deparaffinized using xylene, rehydrated by an ethanol gradient, and performed H&E staining for histological analyses.

Reverse transcription-quantitative (RT-q) PCR analysis

Total RNA was isolated from EPCs using the MiniBEST Universal RNA Extraction Kit (TaKaRa, Kyoto, Japan). RNA was then converted to cDNA via the PrimeScript™ RT Master Mix (TaKaRa). RT-qPCR was performed on StepOnePlus™ Real-Time PCR System (Thermo Fisher Scientific) with TB Green™ Premix EX Taq™ II (Takara), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The β-actin (ACTB) level was used to normalize and determine relative expression values of relevant genes, calculated using the 2−ΔΔCq method [30]. The sequences of oligo-nucleotide primers used are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sequences of the oligo-nucleotide primers used in the RT-qPCR

| Gene | Sequences (5’–3’) |

|---|---|

| HIF1A-F | TTGCTCATCAGTTGCCACTTCC |

| HIF1A-R | GCAATTCATCTGTGCCTTCATTTC |

| Hsp20-F | CTCCAAAATCCAACCAAGCAG |

| Hsp20-R | AATGGGCAAGGGGATGG |

| KDR-F | CTTGGACAGCATCACCAGTAGTCAG |

| KDR-R | TGAGATGCTCCAAGGTCAGGAA |

| PI3K-F | GCATCCCACACATCCTAATCTGAA |

| PI3K-R | GCGTGCAAAGTCAGCAGGAA |

| Akt-F | TCTTCGCTAGCATCGTGTGG |

| Akt-R | GGCGTGATGGTGATCATCTG |

| ACTB-F | CCAAGGCCAACCGTGAGAA |

| ACTB-R | GTCACCGGAGTCCATCACGA |

F forward, R reverse

Western blot analysis

EPCs were rinsed thrice in PBS and dissolved in RIPA buffer containing 1 mmol/l PMSF. Following a 12,000 rpm high-speed centrifugation for 15 min, total proteins were extracted and quantified using the BCA Protein Assay Kit. Equal volumes (20 μl) of proteins were separated using different concentrations of SDS-PAGE electrophoresis and transferred to PVDF membranes, which were then blocked with 5% fat-free milk in TBST for 2 h. Next, the membranes were incubated with primary antibodies for HIF-1α (MA1 –16,518; 1:1000; Invitrogen), Hsp20 (ab13491; 1:20,000; Abcam), KDR (ab39256; 1:1000; Abcam), PI3Kp110 (ab32569; 1:500; Abcam), total-Akt (t-Akt) (9272; 1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology), phosphorylated Akt (p-Akt) (9271; 1:1000; Cell Signaling Technology), and β-Actin (PA5 –19,469; 1:1000; Invitrogen). Upon treatment with appropriate HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies, the protein bands were detected using the Hypersensitive ECL chemiluminescence kit (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) on an iBright™ Imaging System (Thermo Fisher Scientific). ImageJ 1.53d software (National Institutes of Health) was employed to calculate the gray value of examined proteins.

Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as mean ± SD. Differences were analyzed using Student’s t test for two groups and one-way ANOVA for more than two groups. All statistical analyses were calculated using SPSS version 25 (IBM, Chicago, IL, USA). A two-tailed value of p < 0.05 was assigned statistical significance.

Results

The expression of Hsp20 increases during the mobilization of EPCs in the callus of MDO under hypoxic microenvironment

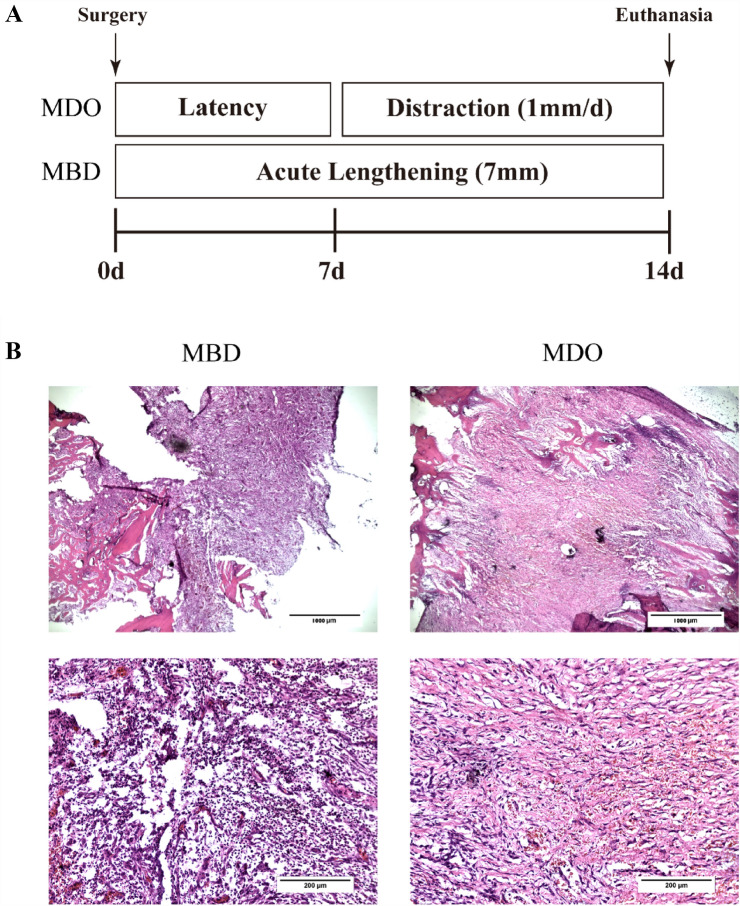

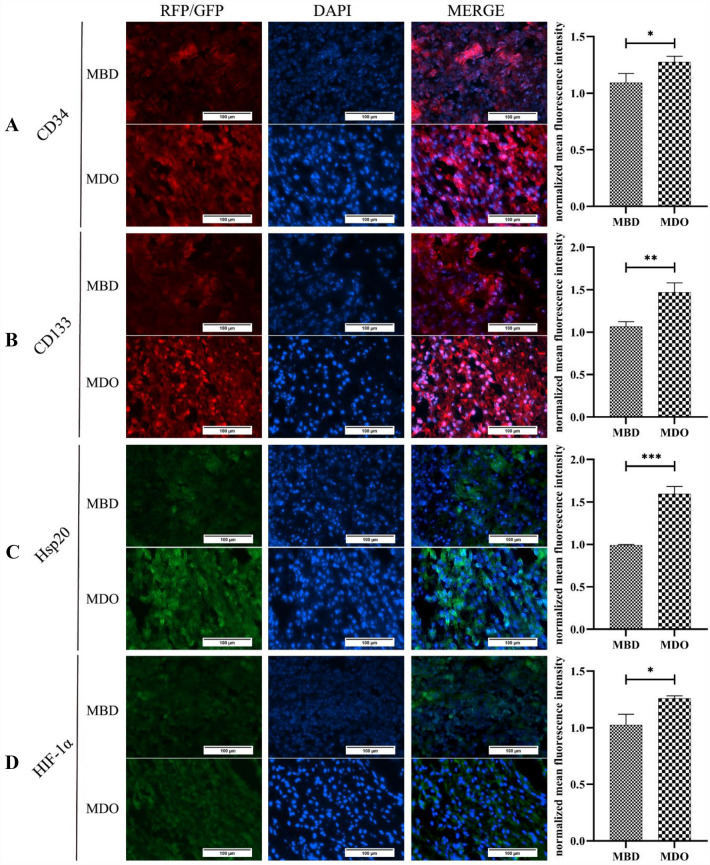

To clarify whether EPCs play a role in MDO-related regeneration, canine MDO and MBD models were established successfully (Fig. 1A). The callus was inspected by H&E staining. Relative to the MBD group, which the callus contained disordered and cluttered fibrous tissue, the callus from the MDO group consisted of larger quantities of organized dense fibrous tissue oriented in the same direction of distraction force after 14 days of regeneration. Moreover, massive red blood cells were observed in the interstitial space, which had consistency with the histopathological changes in the early phase of angiogenesis, whereas considerable inflammatory cells were infiltrated in the callus of MBD group (Fig. 1B). And the expression of CD34 and CD133 in callus of both groups was monitored by immunofluorescence. The results revealed that the expression of CD34 and CD133 was increased largely in the samples of MDO compared with MBD, suggested the mobilization of EPCs in the callus of MDO (Fig. 2A,B). In addition, the expression of HIF-1α and Hsp20 in both groups was also detected. The data showed that the expression of HIF-1α and Hsp20 was upregulated in the samples of MDO compared with MBD, which indicated that Hsp20 was activated during MDO-induced hypoxic condition (Fig. 2C,D).

Fig. 1.

A A schematic diagram of canine MDO and MBD models established in this study. B Representative micrographs of HE-stained callus of MBD and MDO. The callus from the MDO group consisted of larger quantities of organized dense fibrous tissue oriented in the same direction of distraction force, whereas cluttered fibrous tissue and considerable inflammatory cells were contained in the callus of MBD group. Scale bars: 1000 (upper) and 200 (lower) μm

Fig. 2.

A–B Representative images of A CD34, B CD133, C Hsp20, and D HIF-1a expression in the callus of MBD and MDO as detected by immunofluorescent staining assays. The results illustrating that NMFI of CD34, CD133, Hsp20, and HIF-1α was significantly higher in the MDO group, compared to the MBD group. Scale bar, 100 μm. Data expressed as means ± S.D (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001; n = 3 independent experiments)

Appropriate hypoxic microenvironment promotes EPCs viability

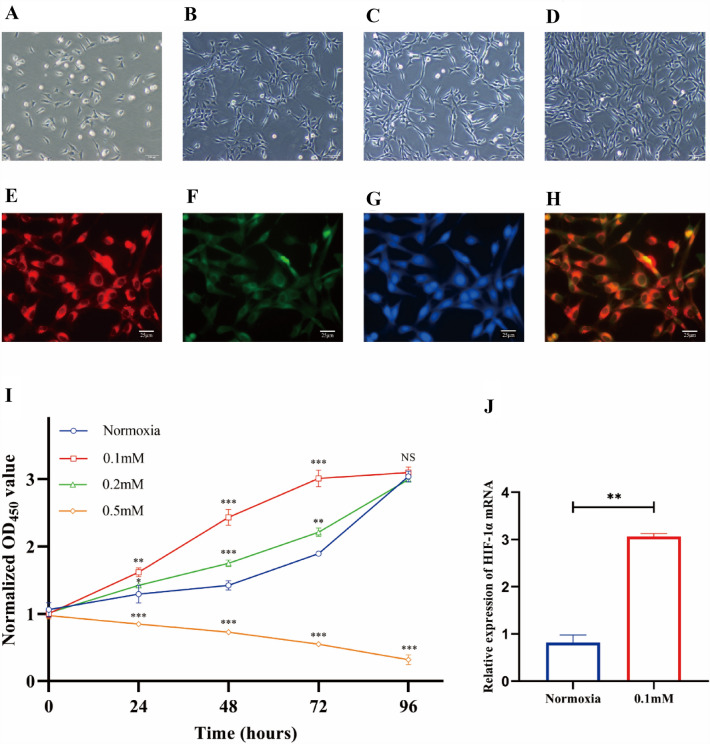

First, the morphology of the initially seeded mononuclear cells was observed at different time points. On day 3, the cells formed a polygonal shape as they attached to the wall (Fig. 3A). During differentiation, the cells exhibited a paving-stone appearance on day 5 (Fig. 3B) and exhibited a spindle-shape, central cluster for 7 days (Fig. 3C). Following 10 days in culture, an endothelial cell-like morphology was observed (Fig. 3D). To further identify the cells as EPCs, we characterized the EPCs as adherent cells positive for Dil-ac-LDL uptake and FITC-UEA-I binding (Fig. 3E–H). Then, we used different concentrations of CoCl2 at varying times to define whether an appropriate hypoxic microenvironment can promote EPCs viability. CCK-8 assay data revealed that 0.1 mM CoCl2 for 48 h provided the most significant effect on EPC viability (Fig. 3I,J). Furthermore, qRCR assay illustrated that these conditions promoted expression of HIF-1α at the transcriptional level (Fig. 3J). This data confirmed that the hypoxic microenvironment was successfully simulated by culturing EPCs in 0.1 mM CoCl2 for 48 h. Thus, we chose this concentration and time point to represent hypoxia in our subsequent experiments.

Fig. 3.

A–D The morphology of canine EPCs (× 100). The EPCs formed a polygonal shape on day 3 (A), a paving-stone appearance on day 5 (B), a central cluster of spindle-shape on day 7 (C), and an endothelial cell-like morphology on day 10 (D). E–H The identification of canine EPCs (× 400). The EPCs absorbed Dil-ac-LDL into the cytoplasm, thereby emitting red fluorescence (E) and interacted with FITC-UEA-I at the membranal level, thereby projecting green fluorescence (F). The DAPI-stained nuclei presented blue fluorescence (G) and the merged color of red and green showed yellow (H). I–J Stimulation of hypoxic microenvironment in EPCs. Cell viability of EPCs was determined using CCK-8 assays after incubation with varying concentrations of CoCl2 for 24, 48, 72, and 96 h, all the groups of different concentration are compared with the group of normoxia at the time point of 0 h (I). The HIF-1α expression was increased in the 0.1 mM CoCl2 group, relative to controls (J). Data presented as means ± S.D (NS, no significance; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001; n = 3 independent experiments)

Hypoxia regulates EPCs proliferation, apoptosis, migration, and tube formation

We next investigated the potential effects of hypoxic microenvironment on the proliferation of EPCs. To evaluate cell cycle progression, we employed flow cytometry. As shown in Fig. 4A–C, the percentage of EPCs entering the S and G2 phases were both significantly higher in the hypoxic group than in the normoxic group. Next, the apoptosis rate of EPCs was detected via annexin V-FITC/PI double staining. Flow cytometric analysis revealed that the apoptotic rate of EPCs was significantly decreased in the hypoxic group, compared to the normoxic group. In addition, the necrotic rate showed no significance between the two groups (Fig. 4D–F). Next, the transwell assay was used to detect EPC migration, and the results revealed that hypoxia significantly promoted EPC migration, relative to normoxia (Fig. 4G–I). Furthermore, we performed in vitro angiogenesis assay to estimate the influence of hypoxia in tube formation of EPCs. The results revealed that hypoxia profoundly increased EPC branch formation, compared to the normoxic group (Fig. 4J–L).

Fig. 4.

A–C Hypoxia regulates cell cycle of EPCs. Cell cycle progression assays illustrating significantly more cells in the S + G2 phase in the hypoxic group, compared to the normoxic group. D–F Hypoxia reduced apoptosis of EPCs. Annexin V-FITC/PI double staining assays confirming that the apoptotic rate of EPCs was significantly lower in the hypoxic group, compared to the normoxic group. G–I Hypoxia promoted migration of EPCs (× 200). The transwell assays revealed the migratory cell numbers were significantly higher in the hypoxic group, compared to the normoxic group. J–L Hypoxia enhanced tube formation of EPCs in vitro (× 100). The tube formation assays illustrating that the number of branches in the hypoxic group was significantly higher than in the normoxic group. Data presented as means ± S.D (NS, no significance; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001; n = 3 independent experiments)

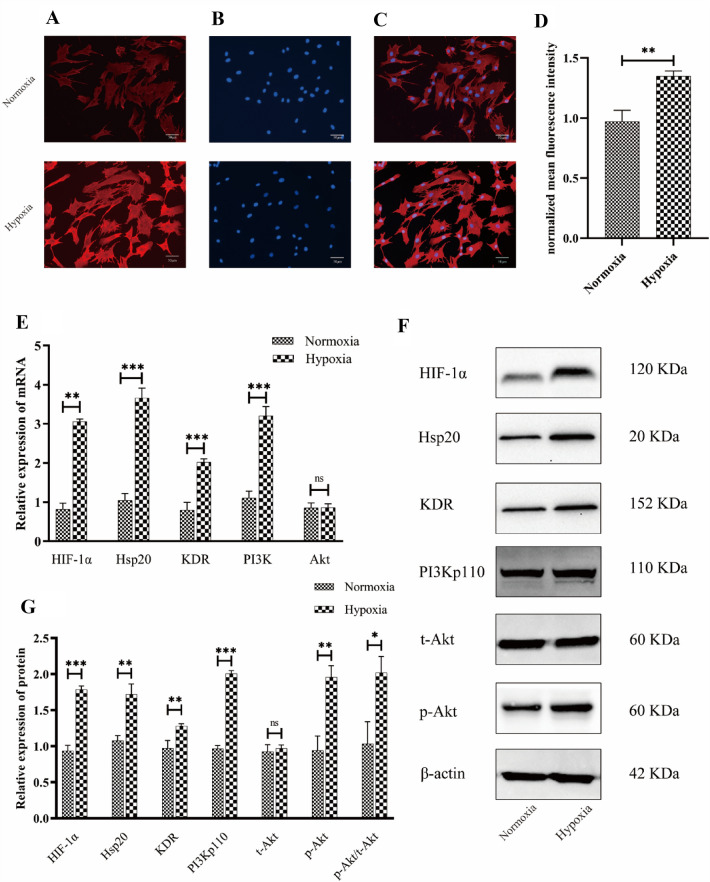

Hypoxia promotes expression of Hsp20 and activates the KDR/PI3K/Akt signaling pathway

To detect whether hypoxia promotes Hsp20 expression, we analyzed Hsp20 expression in EPCs using immunofluorescence. Based on our results, NMFI was significantly increased in the hypoxic group, compared to the normoxic group (Fig. 5A–D). Furthermore, to detect whether hypoxia regulated the KDR/PI3K/Akt signaling pathway, we employed RT-qPCR and western blot assays to analyze the expression of HIF-1α/Hsp20/KDR/PI3K/Akt at both the transcriptional and translational levels. Based on our RT-qPCR assay, the HIF-1α/Hsp20/KDR/PI3K expression in the hypoxic group was remarkably increased, compared to the normoxic group; while the expression of Akt showed no significant change between the two groups (Fig. 5E). Based on our western blot assay, the HIF-1α/Hsp20/KDR/PI3Kp110 expression was massively increased in the hypoxic group, compared to the normoxic group. Moreover, although the expression of t-Akt showed no significant change between the two groups, the expression of p-Akt/t-Akt ratio was drastically increased in the hypoxic group, compared to the normoxic group (Fig. 5F,G).

Fig. 5.

A–D Hypoxia promotes expression of Hsp20 in EPCs. Representative images (× 200) of Hsp20 expression (A) as detected by immunofluorescent staining assays. Nuclei (B) stained with DAPI, and the merged images (C). The results (D) illustrating that NMFI was significantly higher in the hypoxic group, compared to the normoxic group. E–G Hypoxia promoted HIF-1α, Hsp20, KDR, PI3K, and p-Akt expressions in EPCs. RT-qPCR results (E) depicting increased expressions of HIF-1α, Hsp20, KDR, and PI3K in the hypoxic group, compared to the normoxic group, whereas, Akt expression remained the same. Representative images of western blot assays (F). Results (G) depicting increased expression of HIF-1α, Hsp20, KDR, PI3Kp110, p-Akt, and p-Akt/t-Akt in the hypoxic group, compared to the normoxic group, whereas the t-Akt expression remained the same. Data expressed as means ± S.D (NS, no significance; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001; n = 3 independent experiments)

Hsp20 overexpression and knockdown regulate EPCs proliferation, apoptosis, migration, and tube formation

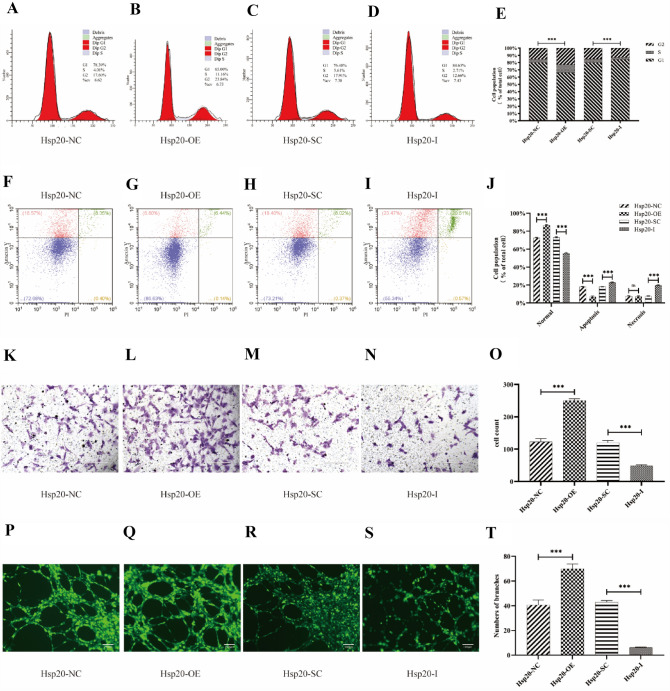

To further explore the role of Hsp20 in EPC angiogenesis, Hsp20 was overexpressed or knocked down in primary EPCs using either Hsp20-OE or Hsp20-I lentivirus, and both times it achieved ≥ 80% transduction efficiency, as certified by fluorescent microscopy. To clarify whether Hsp20 overexpression or knockdown regulates EPC function, several experiments were applied. Firstly, the cell cycle progression test was evaluated via flow cytometry and it assessed cell proliferation. As shown in Fig. 6A–E, the percentage of EPCs entering the cell cycle was significantly higher in the Hsp20-OE group, compared to the Hsp20-NC group. On contrary, the percentage of EPCs entering the cell cycle was significantly lower in the Hsp20-I group, compared to the Hsp20-SC group. Moreover, we employed annexin V-FITC/PI double staining and flow cytometry to detect the apoptotic rate of EPCs. Based on our results, the apoptotic rate of EPCs was significantly decreased in the Hsp20-OE group, compared to the Hsp20-NC group, and it was increased in the Hsp20-I group, relative to the Hsp20-SC group (Fig. 6F–J). Next, we employed the transwell assay to determine the migratory pattern of EPCs. Our data revealed that Hsp20 overexpression promoted EPC migration, compared to the Hsp20-NC group. In contrast, Hsp20 knockdown reduced EPC migration, compared to the Hsp20-SC group (Fig. 6K–O). Lastly, we performed the in vitro angiogenesis assay to estimate the influence of Hsp20 in EPC tube formation. Our data revealed that Hsp20 overexpression profoundly increased EPC branch formation, compared to the Hsp20-NC group. However, Hsp20 knockdown impaired EPC branch formation, compared to the Hsp20-SC group (Fig. 6P–T).

Fig. 6.

A–E Hsp20 regulates cell cycle of EPCs. The cell cycle progression assays depicting the increased accumulation of cells in the S + G2 phase in the Hsp20-OE group, compared to controls. In contrast, Hsp20-I produced the opposite effect, relative to controls. F–J Hsp20 regulated apoptosis of EPCs. Annexin V-FITC/PI double staining assays depicting the reduced apoptotic rate of EPCs in the Hsp20-OE group, relative to controls, whereas, the apoptotic and necrosis rates of EPCs were higher in the Hsp20-I group, relative to controls. K–O Hsp20 regulated migration of EPCs (× 200). The transwell assays revealing the increased migration of cells in the Hsp20-OE group, relative to controls, whereas, Hsp20-I produced the opposite effect. P–T Hsp20 regulated tube formation of EPCs in vitro (× 100). The tube formation assays depicting elevated number of branches in the Hsp20-OE group, relative to controls, whereas, the Hsp20-I group had lower number of branches. Data expressed as means ± S.D (NS, no significance; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001; n = 3 independent experiments)

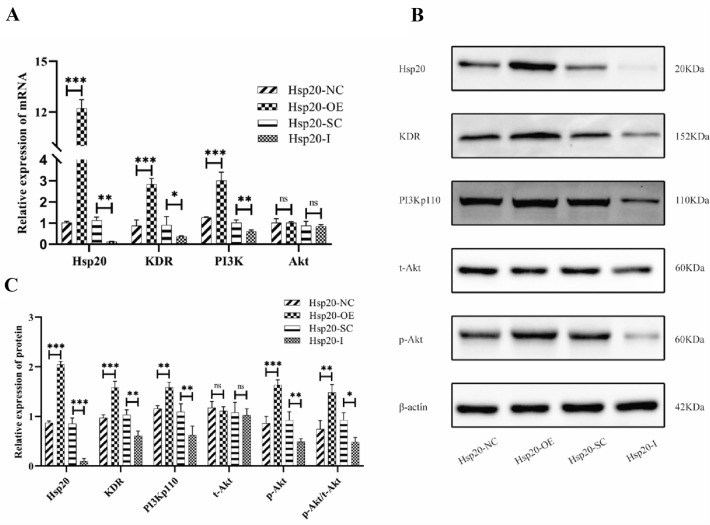

Hsp20 overexpression and knockdown mediate EPCs functions by targeting the KDR/PI3K/Akt signaling pathway

To detect whether Hsp20 overexpression or knockdown regulates the KDR/PI3K/Akt signaling pathway, we conducted both RT-qPCR and western blot assays to analyze the expression of the Hsp20/KDR/PI3K/Akt genes and proteins. Based on our RT-qPCR assay, the Hsp20/KDR/PI3K expression increased significantly in the Hsp20-OE group, compared to the Hsp20-NC group, and markedly decreased in the Hsp20-I group, compared to the Hsp20-SE group. However, the Akt expression showed no significant change among these groups (Fig. 7A). Based on our western blot assay, the Hsp20/KDR/PI3Kp110 expression increased significantly in the Hsp20-OE group, and decreased drastically in the Hsp20-I group. Moreover, although the t-Akt expression showed no significant change among those groups, the p-Akt/t-Akt ratio was markedly increased in the Hsp20-OE group, and decreased in the Hsp20-I group, relative to controls (Fig. 7B,C).

Fig. 7.

A–C Hsp20 regulates expression of Hsp20, KDR, PI3K, and p-Akt in EPCs. RT-qPCR results (A) illustrating increased expression of Hsp20, KDR, and PI3K in the Hsp20-OE group, relative to controls, whereas, Hsp20-I produced the opposite effect. Interestingly, the Akt expression remained the same in all groups. Representative images of western blot assays (B). Results (C) depicting the increased expression of Hsp20, KDR, PI3Kp110, p-Akt, and p-Akt/t-Akt in the Hsp20-OE group, whereas Hsp20-I produced the opposite effect. Notably, the t-Akt expression showed no significant difference among all groups. Data presented as means ± SD (NS, no significance; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001; n = 3 independent experiments)

Discussion

In clinical application, MDO is greatly limited due to its long period of consolidation. Stem cells, such as, EPCs shorten this period via accelerating the angiogenic and osteogenic processes. Since their discovery by Asahara [5], an increasing number of animal studies validated the unique role of EPCs in treating numerous diseases, such as, improvement of blood supply in limb ischemia [31], rescue of myocardium from myocardial ischemia [32], enhancement of blood supply after acute kidney injury [33], assistance in islet cells survival [34], and so on. All experiments illustrated that EPCs and/or EPC-mediated secretions like exosomes promote damaged tissue regeneration by initiating angiogenesis in situ. This means that angiogenesis is the most crucial step in tissue regeneration, and even more so in distraction osteogenesis. Even though several studies reported on the existence of EPCs and/or their accumulation in the distraction gap [11, 35–37], there are only a few studies that focus on EPC functions in distraction osteogenesis. Our research group recently revealed that EPCs promote angiogenesis and osteogenesis during MDO by targeting the NOTCH2 signal pathway [38]. But, additional molecular mechanisms that regulate EPC-mediated angiogenesis need further exploration.

There is evidence that the hypoxic microenvironment in distraction osteogenesis promotes angiogenesis via activation of the HIF-1α/VEGF [39] or HIF-1α/Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathways [40]. Our results confirmed the existence of hypoxic microenvironment in MDO. Noteworthy, in constract to the above signaling pathway, increased expreesion of Hsp20 and HIF-1α in the same period suggested a novel signaling pathway in MDO-regulated regeneration. Additionally, in terms of the hypoxic effects on EPCs, it was shown that HIF-1α, a key protein, strongly regulates EPCs mobilization and function [41]. Our research also confirmed that HIF-1α overexpression in EPCs, by simulating hypoxic conditions using 0.1 mM CoCl2, promotes cell proliferation, migration, and tube formation ability, while reducing apoptotic rate. These results indicate that enhanced HIF-1α expression promotes angiogenesis by augmenting transcription and translation of multiple cytokines, such as, Hsp20. Hsp20, in most cases, serves as a molecular chaperone [42]. But, several studies revealed an unusual behavior of Hsp20, which is to act as a key signal transductor molecule to promote angiogenesis by activating the KDR/PI3K/Akt signaling pathway [21, 22, 26].

Based on our data, the Hsp20 expression in EPCs, cultured in an hypoxic microenvironment, was significantly increased, relative to controls. This suggests that HIF-1α activates the transcription and translation of Hsp20 in EPCs, under hypoxic conditions. In line with previous studies which proved Hsp20 could improve cell functions in trophoblast cells and cardiomyocytes via PI3K/Akt signaling pathway [43–45], we also observed that the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway was markedly activated with the increased expression of Hsp20 in EPCs in Fig. 5. The PI3K/Akt signaling pathway also play critical roles in cell survival, proliferation, apoptosis, and autophagy besides angiogenesis [46]. Combined with our data, it is very likely that the Hsp20-based EPC regulatory functions is carried out via the KDR/PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. To further illustrate this phenomenon, we examined functions in EPCs incorporated with Hsp20-OE and Hsp20-I. Our data revealed that Hsp20 overexpression promotes cell proliferation, migration, tube formation ability, and decreases apoptotic rate of EPCs, whereas Hsp20 inhibition produces the opposite effect. This further confirms that Hsp20 indeed plays a key role in EPC-mediated angiogenesis in vitro. Mechanistically, the results of the RT-qPCR and western blot assays revealed that Hsp20 exerts its angiogenic role by regulating the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. Together, we validated that the Hsp20/KDR/PI3K/Akt signaling pathway regulates EPC tube formation in vitro. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time an Hsp20-related function in EPCs was revealed.

Recently, it was recognized that adult EPCs are not a single, homogeneous stem cell population [47]. In fact, the adult EPCs are now identified by surface markers into two categories [48, 49]: myeloid angiogenic cells (MACs) that present CD45 + and VEGFR2 + , and endothelial colony-forming cells (ECFCs) that present CD31 + , CD34 + , CD45−, and VEGFR2−. However, it was confirmed that both EPCs types contribute to angiogenesis in ischemic tissue in different ways [50]. Briefly, MACs that do not differentiate into endothelial cells in vivo support angiogenic growth via autocrine and/or paracrine mechanisms. In contrast, ECFCs primarily assist angiogenesis by differentiating into endothelial cells and forming tubes in vivo. In our research, we demonstrated that the KDR expression was evident both at the transcriptional and translational levels. This may suggest that the EPCs used in this research were partly were MACs. When MACs are maintained under hypoxic conditions, the HIF protein activates cells to secrete Hsp20 for autocrine and/or paracrine signaling. Initially, MACs reduplicate themselves and reduce the apoptotic rate via autocrine signaling. But soon afterwards, ECFCs receive signal from Hsp20 and form tubes via activation of the KDR/PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. However, the Hsp20 effects on the two different types of cells still remain uncertain, and needs further investigation. A comprehensive understanding of the effects of Hsp20 on EPCs will enable a new therapeutic target for shortening the consolidation period during distraction osteogenesis.

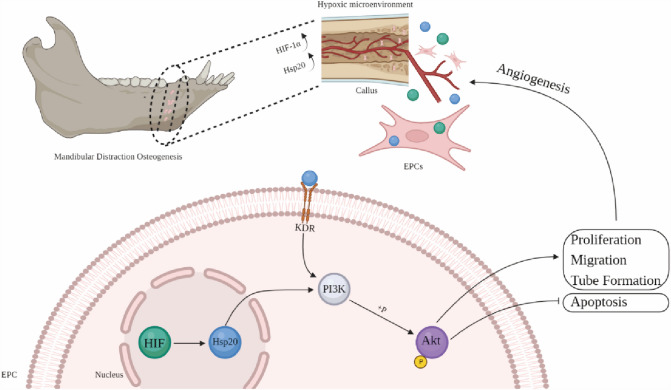

In conclusion, the present study is the first to explore Hsp20 as a novel regulator of the KDR/PI3K/Akt signaling pathway, which enhances canine EPCs functions under hypoxic conditions. We demonstrated that Hsp20 overexpressed in the callus of MDO and the Hsp20 overexpression in canine EPCs enhanced cell proliferation, migration, and tube formation via both autocrine and/or paracrine mechanism in vitro; while Hsp20 inhibition produced the opposite effects (Fig. 8). Therefore, these novel findings offer great clinical implications in the EPCs-assisted distraction osteogenesis surgery. Together, these data illustrate a novel signaling pathway that regulates angiogenesis, and features important directions for future clinical research.

Fig. 8.

A schematic diagram illustrating the regulation of EPC-mediated angiogenesis via Hsp20 in MDO under a hypoxic microenvironment (Created with BioRender.com). During MDO-related tissue regeneration, the callus is in a hypoxic environment. With the mobilization of EPCs in callus, upregulated Hsp20 can target KDR to gradually increase and positively regulate PI3K activity and AKT phosphorylation, thus promoting EPCs proliferation, migration, and tube formation during MDO

Declarations

Conflict of interest

All of the authors had no any personal, financial, commercial, or academic conflicts of interest separately.

Ethical statement

The present study was approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Guangxi Medical University (IACUC No. SCXK GUI 2009–0002).

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Zhiqi Han and Xuan He have contributed equally to this work and should be considered as co-first authors.

Change history

10/31/2022

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1007/s13770-022-00494-w

Contributor Information

Nuo Zhou, Email: gxzhounuo@sina.cn.

Xuanping Huang, Email: hxp120@126.com.

References

- 1.McCarthy JG, Schreiber J, Karp N, Thorne CH, Grayson BH. Lengthening the human mandible by gradual distraction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1992;89:1–8; discussion 9–10. [PubMed]

- 2.Nørholt SE, Jensen J, Schou S, Pedersen TK. Complications after mandibular distraction osteogenesis: a retrospective study of 131 patients. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2011;111:420–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Compton J, Fragomen A, Rozbruch SR. Skeletal repair in distraction osteogenesis: mechanisms and enhancements. JBJS Rev. 2015;3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Filipowska J, Tomaszewski KA, Niedźwiedzki Ł, Walocha JA, Niedźwiedzki T. The role of vasculature in bone development, regeneration and proper systemic functioning. Angiogenesis. 2017;20:291–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Asahara T, Murohara T, Sullivan A, Silver M, van der Zee R, Li T, et al. Isolation of putative progenitor endothelial cells for angiogenesis. Science. 1997;275:964–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Jia Y, Zhu Y, Qiu S, Xu J, Chai Y. Exosomes secreted by endothelial progenitor cells accelerate bone regeneration during distraction osteogenesis by stimulating angiogenesis. Stem Cell Res Therapy. 2019;10:12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Kimura W, Xiao F, Canseco DC, Muralidhar S, Thet S, Zhang HM, et al. Hypoxia fate mapping identifies cycling cardiomyocytes in the adult heart. Nature. 2015;523:226–30. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Mantel CR, O'Leary HA, Chitteti BR, Huang X, Cooper S, Hangoc G, et al. Enhancing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation efficacy by mitigating oxygen shock. Cell. 2015;161:1553–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Abd El Aziz MT, Abd El Nabi EA, Abd El Hamid M, Sabry D, Atta HM, Rahed LA, et al. Endothelial progenitor cells regenerate infracted myocardium with neovascularisation development. J Adv Res. 2015;6:133–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.He X, Han Z, Jiang W, Huang F, Ren C, Wei Q, et al. Hypoxia improved vasculogenesis in distraction osteogenesis through Mesenchymal-Epithelial transition (MET), Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, and autophagy. Acta Histochem. 2020;122:151593. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Lee DY, Cho TJ, Lee HR, Park MS, Yoo WJ, Chung CY, et al. Distraction osteogenesis induces endothelial progenitor cell mobilization without inflammatory response in man. Bone. 2010;46:673–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Jiang X, Zhang Y, Fan X, Deng X, Zhu Y, Li F. The effects of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1α protein on bone regeneration during distraction osteogenesis: an animal study. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2016;45:267–72. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Xu J, Sun Y, Wu T, Liu Y, Shi L, Zhang J, et al. Enhancement of bone regeneration with the accordion technique via HIF-1α/VEGF activation in a rat distraction osteogenesis model. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2018;12:e1268-e76. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Hamushan M, Cai W, Zhang Y, Lou T, Zhang S, Zhang X, et al. High-purity magnesium pin enhances bone consolidation in distraction osteogenesis model through activation of the VHL/HIF-1α/VEGF signaling. J Biomater Appl. 2020;35:224–36. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Chen B, Feder ME, Kang L. Evolution of heat-shock protein expression underlying adaptive responses to environmental stress. Mol Ecol. 2018;27:3040–54. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Mymrikov EV, Seit-Nebi AS, Gusev NB. Large potentials of small heat shock proteins. Physiol Rev. 2011;91:1123–59. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Fan GC, Ren X, Qian J, Yuan Q, Nicolaou P, Wang Y, et al. Novel cardioprotective role of a small heat-shock protein, Hsp20, against ischemia/reperfusion injury. Circulation. 2005;111:1792–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Pulakazhi Venu VK, Saifeddine M, Mihara K, El-Daly M, Belke D, Dean JLE, et al. Heat shock protein-27 and sex-selective regulation of muscarinic and proteinase-activated receptor 2-mediated vasodilatation: differential sensitivity to endothelial NOS inhibition. Br J Pharmacol. 2018;175:2063–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Lu C, Zhang X, Zhang D, Pei E, Xu J, Tang T, et al. Short time tripterine treatment enhances endothelial progenitor cell function via heat shock protein 32. J Cell Physiol. 2015;230:1139–47. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Lee SP, Youn SW, Cho HJ, Li L, Kim TY, Yook HS, et al. Integrin-linked kinase, a hypoxia-responsive molecule, controls postnatal vasculogenesis by recruitment of endothelial progenitor cells to ischemic tissue. Circulation. 2006;114:150–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Fan GC, Zhou X, Wang X, Song G, Qian J, Nicolaou P, et al. Heat shock protein 20 interacting with phosphorylated Akt reduces doxorubicin-triggered oxidative stress and cardiotoxicity. Circ Res. 2008;103:1270–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Zhang X, Wang X, Zhu H, Kranias EG, Tang Y, Peng T, et al. Hsp20 functions as a novel cardiokine in promoting angiogenesis via activation of VEGFR2. PloS One. 2012;7:e32765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Holmes K, Roberts OL, Thomas AM, Cross MJ. Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2: structure, function, intracellular signalling and therapeutic inhibition. Cell Signal. 2007;19:2003–12. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Welham MJ, Kingham E, Sanchez-Ripoll Y, Kumpfmueller B, Storm M, Bone H. Controlling embryonic stem cell proliferation and pluripotency: the role of PI3K- and GSK-3-dependent signalling. Biochem Soc Trans. 2011;39:674–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Everaert BR, Van Craenenbroeck EM, Hoymans VY, Haine SE, Van Nassauw L, Conraads VM, et al. Current perspective of pathophysiological and interventional effects on endothelial progenitor cell biology: focus on PI3K/AKT/eNOS pathway. Int J Cardiol. 2010;144:350–66. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Wang X, Zhao T, Huang W, Wang T, Qian J, Xu M, et al. Hsp20-engineered mesenchymal stem cells are resistant to oxidative stress via enhanced activation of Akt and increased secretion of growth factors. Stem Cells. 2009;27:3021–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Jiang W, Zhu P, Huang F, Zhao Z, Zhang T, An X, et al. The RNA Methyltransferase METTL3 Promotes Endothelial Progenitor Cell Angiogenesis in Mandibular Distraction Osteogenesis via the PI3K/AKT Pathway. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9:720925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Liu D, Zhao Z, Jiang W, Zhu P, An X, Xie Y, et al. Panax notoginseng saponin promotes bone regeneration in distraction osteogenesis via the TGF-β1 signaling pathway. Evidence-Based Complementary Alternative Med eCAM. 2021;2021:2895659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Jensen EC. Quantitative analysis of histological staining and fluorescence using ImageJ. Anat Rec (Hoboken). 2013;296:378–81. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. 2001;25:402–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Sarlon G, Zemani F, David L, Duong Van Huyen JP, Dizier B, Grelac F, et al. Therapeutic effect of fucoidan-stimulated endothelial colony-forming cells in peripheral ischemia. J Thromb Haemost. 2012;10:38–48. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Tan Q, Qiu L, Li G, Li C, Zheng C, Meng H, et al. Transplantation of healthy but not diabetic outgrowth endothelial cells could rescue ischemic myocardium in diabetic rabbits. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 2010;70:313–21. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Burger D, Viñas JL, Akbari S, Dehak H, Knoll W, Gutsol A, et al. Human endothelial colony-forming cells protect against acute kidney injury: role of exosomes. Am J Pathol. 2015;185:2309–23. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Coppens V, Heremans Y, Leuckx G, Suenens K, Jacobs-Tulleneers-Thevissen D, Verdonck K, et al. Human blood outgrowth endothelial cells improve islet survival and function when co-transplanted in a mouse model of diabetes. Diabetologia. 2013;56:382–90. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Cetrulo CL, Jr., Knox KR, Brown DJ, Ashinoff RL, Dobryansky M, Ceradini DJ, et al. Stem cells and distraction osteogenesis: endothelial progenitor cells home to the ischemic generate in activation and consolidation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;116:1053–64; discussion 65–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Fujio M, Yamamoto A, Ando Y, Shohara R, Kinoshita K, Kaneko T, et al. Stromal cell-derived factor-1 enhances distraction osteogenesis-mediated skeletal tissue regeneration through the recruitment of endothelial precursors. Bone. 2011;49:693–700. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Ando Y, Matsubara K, Ishikawa J, Fujio M, Shohara R, Hibi H, et al. Stem cell-conditioned medium accelerates distraction osteogenesis through multiple regenerative mechanisms. Bone. 2014;61:82–90. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Jiang W, Zhu P, Zhang T, Liao F, Yu Y, Liu Y, et al. MicroRNA-205 mediates endothelial progenitor functions in distraction osteogenesis by targeting the transcription regulator NOTCH2. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2021;12:101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Mori S, Akagi M, Kikuyama A, Yasuda Y, Hamanishi C. Axial shortening during distraction osteogenesis leads to enhanced bone formation in a rabbit model through the HIF-1alpha/vascular endothelial growth factor system. J Orthop Res. 2006;24:653–63. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Song J, Ye B, Liu H, Bi R, Zhang N, Hu J, et al. Fak-Mapk, Hippo and Wnt signalling pathway expression and regulation in distraction osteogenesis. Cell Proliferat. 2018;51:e12453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Zan T, Li H, Du Z, Gu B, Liu K, Li Q. Enhanced endothelial progenitor cell mobilization and function through direct manipulation of hypoxia inducible factor-1α. Cell Biochem Funct. 2015;33:143–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Li F, Xiao H, Zhou F, Hu Z, Yang B. Study of HSPB6: Insights into the properties of the multifunctional protective agent. Cellular Physiol Biochem Int J Exp Cellular Physiol Biochem Pharmacol. 2017;44:314–32. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Wang X, Gu H, Huang W, Peng J, Li Y, Yang L, et al. Hsp20-Mediated activation of exosome biogenesis in cardiomyocytes improves cardiac function and angiogenesis in diabetic mice. Diabetes. 2016;65:3111–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Li F, Xie Y, Wu Y, He M, Yang M, Fan Y, et al. HSP20 Exerts a protective effect on preeclampsia by regulating function of trophoblast cells via Akt pathways. Reproductive Sci. 2019;26:961–71. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Yu DW, Ge PP, Liu AL, Yu XY, Liu TT. HSP20-mediated cardiomyocyte exosomes improve cardiac function in mice with myocardial infarction by activating Akt signaling pathway. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2019;23:4873–81. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.Liu P, Begley M, Michowski W, Inuzuka H, Ginzberg M, Gao D, et al. Cell-cycle-regulated activation of Akt kinase by phosphorylation at its carboxyl terminus. Nature. 2014;508:541–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Díaz Del Moral S, Barrena S, Muñoz-Chápuli R, Carmona R. Embryonic circulating endothelial progenitor cells. Angiogenesis. 2020;23:531–41. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48.Medina RJ, Barber CL, Sabatier F, Dignat-George F, Melero-Martin JM, Khosrotehrani K, et al. Endothelial progenitors: A consensus statement on nomenclature. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2017;6:1316–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Chopra H, Hung MK, Kwong DL, Zhang CF, Pow EHN. Insights into endothelial progenitor cells: origin, classification, potentials, and prospects. Stem Cells Int. 2018;2018:9847015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.Minami Y, Nakajima T, Ikutomi M, Morita T, Komuro I, Sata M, et al. Angiogenic potential of early and late outgrowth endothelial progenitor cells is dependent on the time of emergence. Int J Cardiol. 2015;186:305–14. [DOI] [PubMed]