Abstract

Halomethoxybenzenes (HMBs) are a group of compounds with natural and anthropogenic origins. Here we extend a 2002–2015 survey of bromoanisoles (BAs) in the air and precipitation at Råö on the Swedish west coast and Pallas in Subarctic Finland. New BAs data are reported for 2018 and 2019 and chlorinated HMBs are included for these and some previous years: drosophilin A methyl ether (DAME: 1,2,4,5-tetrachloro-3,6-dimethoxybenzene), tetrachloroveratrole (TeCV: 1,2,3,4-tetrachloro-5,6-dimethoxybenzene), and pentachloroanisole (PeCA). The order of abundance of HMBs at Råö was ΣBAs > DAME > TeCV > PeCA, whereas at Pallas the order of abundance was DAME > ΣBAs > TeCA > PeCA. The lower abundance of BAs at Pallas reflects its inland location, away from direct marine influence. Clausius-Clapeyron (CC) plots of log partial pressure (Pair)/Pa versus 1/T suggested distant transport at both sites for PeCA and local exchange for DAME and TeCV. BAs were dominated by distant transport at Pallas and by both local and distant sources at Råö. Relationships between air and precipitation concentrations were examined by scavenging ratios, SR = (ng m−3)precip/(ng m−3)air. SRs were higher at Pallas than Råö due to greater Henry's law partitioning of gaseous compounds into precipitation at colder temperatures. DAME is produced by terrestrial fungi. We screened 19 fungal species from Swedish forests and found seven of them contained 0.01–3.8 mg DAME per kg fresh weight. We suggest that the volatilization of DAME from fungi and forest litter containing fungal mycelia may contribute to atmospheric levels at both sites.

Keywords: Halomethoxybenzenes (HMBs), Bromoanisoles (BAs), Drosophilin A methyl ether (DAME), Tetrachloroveratrole (TeCV), Atmospheric transport, Sources

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Halomethoxybenzenes (HMBs) were found in the air at Nordic coastal and inland sites.

-

•

Brominated HMBs are produced in the marine environment.

-

•

One chlorinated HMB was found in terrestrial fungi and forest litter.

-

•

No significant trends in the air were found between 2002 and 2019 for any HMBs.

-

•

Both regional and distant air transport were indicated.

1. Introduction

Halomethoxybenzenes (HMBs: anisoles, veratroles, and related compounds), a group of compounds with natural and anthropogenic origins [1,2], are found in the air worldwide from the southern and northern hemispheres, over oceans and in polar regions [[1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13]]. Typical HMBs in the atmosphere are chloro-, bromo- and mixed chlorobromo-anisoles, and halogenated dimethoxy compounds [1,2,10].

Bromophenols (BPs) have well-known natural production by marine bacteria, phytoplankton, macroalgae, invertebrates [7,[14], [15], [16]] and multiple anthropogenic sources [17,18]. O-methylation of BPs produces bromoanisoles (BAs) [19]. Chloroanisoles (CAs) are thought to be mainly anthropogenic [2], although structurally related “chlorinated anisyl metabolites” and other chlorinated organic compounds are synthesized by terrestrial fungi [[20], [21], [22]]. Pentachloroanisole (PeCA) is a metabolite of the wood preservative pentachlorophenol (PeCP) [23] and is common in the air [[1], [2], [3], [4],[8], [9], [10], [11], [12],24,25]; however, continent-wide spatial patterns of PeCA and PeCP in pine needles suggest separate origins [26]. CAs and BAs are “taste and odor” compounds arising from the disinfection of drinking water containing halogens [27], infamous for causing “cork taint” in wines [28,29], and mustiness in packaged food [30] and water [31].

Dimethoxylated HMBs reported in air are trichloro- and tetrachloroveratroles (TriCV: 1,2,3-trichloro-5,6-dimethoxybenzene; TeCV: 1,2,3,4-tetrachloro-5,6-dimethoxybenzene), and drosophilin A methyl ether (DAME: 1,2,4,5-tetrachloro-3,6-dimethoxybenzene), an isomer of TeCV. The CVs are O-methylation products of chloroguaicols found in bleached Kraft mill effluent [[31], [32]] from chlorine bleaching of lignin, while DAME, its precursor drosophilin A (DA: 2,3,5,6-tetrachloro-4-methoxyphenol) and related “chlorinated hydroquinone metabolites” are synthesized by terrestrial fungi [20,[33], [34], [35], [36]]. DA has been reported in the meat of wild boar (Sus scrofa), apparently due to consuming fungi [37]. Both DAME and DA have antibacterial properties [34,38]. Threshold toxic concentrations and sublethal effects of several HBMs, including TriCV and TeCV, were reported on zebrafish (Brachydanio rerio) embryos and larvae [32].

Crystals of DAME were discovered in a mesquite (Prosopis juliflora) log decayed by the basiomycete Phellinus badius and the authors suggested that DAME could be released into the atmosphere through biomass burning [33]. Nontarget screening qualitatively revealed chlorinated anisoles and dimethoxybenzenes in Arctic air [39] and DA in Moscow snow [40]. TeCV and PeCA were quantified in Arctic air [8,11] and air and deposition at Lake Victoria, Africa [3].

Previously we reported 2,4-dibromoanisole (DiBA) and 2,4,6-tribromoanisole (TriBA) in the air and deposition on the Atlantic coast of southern Sweden (Råö, 57.39° N, 11.91° E), inland Subarctic Finland (Pallas, 68.00° N, 24.23° E) (Fig. 1), air [5,6] and air-sea exchange [41] in the northern Baltic. Sampling locations are shown on maps in these publications. Air concentrations were in the order Råö > northern Baltic > Pallas and were typical of those in other marine regions of the world [7]. Proportions of TriBA/DiBA decreased inland and northward. BAs were also determined in macroalgae species from the Baltic and Nordic Atlantic regions [15]. These studies concluded that BAs are associated with emissions from Nordic coastal regions and distant transport and that air concentrations and deposition are controlled by the physicochemical properties of the BAs.

Fig. 1.

Annual mean concentrations of HMBs in air at Råö (a) and Pallas (b).

Statistics are reported in Tables S2 and S3.

In this work, we extended measurements of BAs at Råö and Pallas to 2018 and 2019 and determined some chlorinated HMBs in these and previous samples covering 2002–2015. The targeted compounds were DiBA, TriBA, DAME, TeCV, and PeCA. The study was conducted to gain insight into the sources and transport pathways of the chlorinated versus brominated compounds. Considering that fungal sources of DAME are likely, we screened fungi specimens and samples of forest litter.

2. Materials and methods

Air and deposition locations at Råö and Pallas and sampling methods are described in Supplementary Material (SM1-1) and [5]. Briefly, the air was drawn through a glass fiber filter (GFF) followed by a polyurethane foam (PUF) trap. Bulk deposition (wet + dry) was collected in a funnel drained through a GFF-PUF trap. Råö and Pallas are European Monitoring and Evaluation Program (EMEP) stations, and Pallas is in the Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Program (AMAP) network. Sample processing and analysis for 12 polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (Σ12PAHs, see SM1-2), other persistent organic pollutants (POPs, not reported here) surrogates, and internal standards were done at the Swedish Environmental Research Institute (IVL) as previously described [42], and HMBs in cleaned extracts were determined at Umeå University (UmU).

Fruiting bodies of terrestrial fungi and forest litter/underlying humus were collected in Västerbotten and Gävleborg counties, Sweden, in 2021. Homogenized fruiting bodies and litter/humus (0.5–2 g) were extracted by soaking them in ethyl acetate. Extracts were spiked with an internal standard and analyzed without cleanup. Details are given in the SM1-2.

Samples at UmU were analyzed by capillary gas chromatography—electron impact quadrupole mass spectrometry (GC-MSD) with selected ion monitoring, using methods similar to those for BAs [5]. The column, conditions, monitored ions, and quality control are given in the SM1-2.

HMBs are relatively volatile and suffer losses during air sampling on PUF due to breakthroughs. We corrected for this by considering the collection efficiency of a PUF trap as a function of compound volatility (octanol-air and PUF-air partition coefficients, KOA and KPA) and the number of theoretical plates in the PUF cartridge [5,43]. Details are given in the SM3.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. HMB concentrations in air

The range, mean ± SD, and geometric mean concentrations of HMBs in the air at Råö and Pallas over 2002–2019 are listed in Table 1, with annual results in Fig. 1 and Tables S1–S3. The data set for BAs include results previously obtained [5], with a reanalysis of some samples. New results for BAs are from the years 2002, 2018, and 2019 at Råö and 2018 and 2019 at Pallas. DAME, TeCV, and PeCA were determined for the years 2002, 2004, 2014, 2018, and 2019.

Table 1.

Halomethoxybenzenes in the air during 2002–2019 (pg m−3).

| Råö | Range | Mean | SD | Geomean | Npos/Ntot | a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2,4-diBA | 0.4–95 | 26 | 16 | 20 | 143/143 | b |

| 2,4,6-triBA | 1.6–138 | 44 | 28 | 34 | 143/143 | b |

| DAME | 1.9–214 | 36 | 37 | 25 | 67/67 | c |

| TeCV | 0.6–40 | 12 | 8.2 | 9.0 | 67/67 | c |

| PeCA | NDf–7 | 1.7 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 60/66 | c |

| Pallas | ||||||

| 2,4-diBA | ND–89 | 12 | 15 | 6.7 | 95/96 | d |

| 2,4,6-triBA | 0.03–37 | 9.9 | 6.8 | 7.3 | 96/96 | d |

| DAME | 1.4–244 | 54 | 64 | 26 | 48/48 | e |

| TeCV | ND–6.4 | 2.5 | 1.9 | 1.7 | 46/48 | e |

| PeCA | ND–4.7 | 0.84 | 0.83 | 0.52 | 39/48 | e |

a) Npos/Ntot: Number of positive (>LOD)/total samples. LOD/2 was substituted for sample concentrations < LOD (SM2).

b) Years 2002, 2004, 2006, 2012, 2014, 2015, 2018, and 2019. Bold: new in this study.

c) Years 2002, 2004, 2014, 2018, and 2019. Bold: new in this study.

d) Years 2002, 2004, 2006, 2010, 2012, 2014, 2015, 2018, and 2019. Bold: new in this study.

e) Years 2002, 2004, 2014, 2018, and 2019. Bold: new in this study.

f) ND = not detected.

The order of abundance of HMBs at Råö was ΣBAs (DiBA + TriBA) > DAME > TeCV > PeCA, whereas at Pallas the order was DAME > ΣBAs > TeCA > PeCA. The lower abundance of BAs at Pallas reflects its inland location, away from direct marine influence [5].

Concentrations of DAME at Råö and Pallas were similar, whereas TeCV and PeCA at Pallas were lower than at Råö. The proportion of DAME/TeCV was lower at Pallas than at Råö (Fig. 1) for unknown reasons. Correlations among compounds are summarized in Table S4 and Fig. 2 for Råö and Table S5 and Fig. 3 for Pallas. At both stations, correlations were positive and significant (p < 0.05) among ΣBAs, DAME, TeCV, and PeCA.

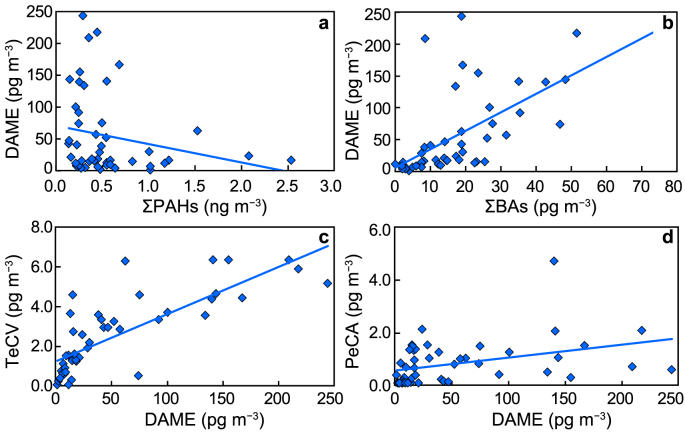

Fig. 2.

Correlations of air concentrations at Råö: a, DAME vs. ΣPAHs; b, DAME vs. ΣBAs; c, TeCV vs. DAME; d, PeCA vs. DAME. All regressions are significant at p < 0.05. Statistics are given in Table S4.

Fig. 3.

Correlations of air concentrations at Pallas: a, DAME vs. ΣPAHs; b, DAME vs. ΣBAs; c, TeCV vs. DAME; d, PeCA vs. DAME. The trendline for DAME vs. ΣPAHs (a) is shown, but the regression is not significant (p > 0.05). Regressions of DAME vs. ΣBAs (b), TeCV vs. DAME (c), and PeCA vs. DAME (d) are significant at p < 0.05. Statistics are given in Table S5.

At Råö, ΣBAs, DAME, and TeCV were negatively and significantly correlated with Σ12PAHs, with no significant association for PeCA. None of the HMBs was significantly correlated with Σ12PAHs at Pallas. Negative or no association of HMBs, particularly DAME, with Σ12PAHs (Fig. 2) seems to contradict the hypothesis of [33]; who suggested that biomass burning could release fungal-derived DAME into the atmosphere. We also examined relationships with BaP since elevated BaP levels have been linked to fires in the Arctic [44]. As for ΣPAHs, DAME showed a negative correlation with BaP at Råö and an insignificant correlation at Pallas (Tables S4 and S5). However, the [33] hypothesis is not necessarily refuted because biomass burning may not be the dominant source of PAHs at these sites. The higher DAME concentrations occur in the warm periods when PAHs are low (Fig. 2, see below) and are likely caused by non-combustive volatilization.

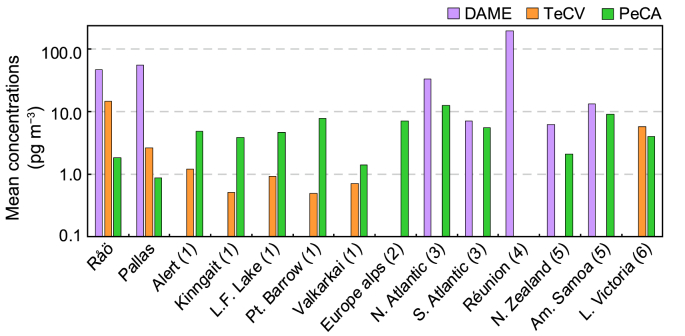

Comparisons of chlorinated HMBs at Råö and Pallas to air concentrations reported previously are shown in Fig. 4. Many of those measurements were made decades ago. Concentrations of DAME at Råö and Pallas are within the range of those reported at open-ocean and island stations. DAME has not been reported at Arctic stations in Canada, Russia, and the US. TeCV levels at Råö and Pallas are higher than measurements at other Arctic stations and surprisingly similar to concentrations reported at Lake Victoria, Africa. PeCA concentrations at Råö and Pallas tend to be below the other reported values.

Fig. 4.

Mean concentrations of the chlorinated HMBs DAME, TeCV, and PeCA at Råö and Pallas and reported in other studies. (1) Canadian Arctic: Alert, Kinngait, Little Fox Lake; Alaska: Point Barrow; Russian Arctic: Valkarkai, summarized by [11]. (2) European alps, [24]. (3) North and South Atlantic, [9,10]. (4) Réunion, [12]. (5) New Zealand and American Samoa, [4]. (6) Lake Victoria, Africa, [3].

3.2. Temperature relationships and trends

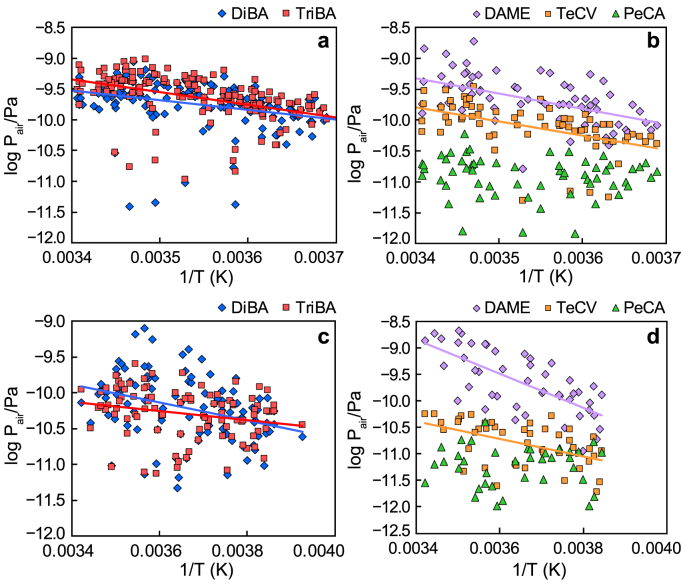

Clausius-Clapeyron (CC) plots of log partial pressure in air (Pair/Pa) versus reciprocal temperature are shown in Fig. 5 for BAs, DAME, TeCV, and PeCA. Regression statistics are given in Table S5. The BAs dataset consists of measurements reported earlier [5] plus new results reported here (see above). CC slopes at both sites were significant for DiBA, TriBA, DAME, and TeCV, but not for PeCA.

Fig. 5.

Temperature relationships for BAs, DAME, TeCV, and PeCA at Råö (a–b) and Pallas (c–d). Regression parameters for significant relationships (p < 0.05) of BAs, DAME, and TeCV are given in Table S5, those for PeCA are not significant.

Site-specific CC slopes which are similar to those for liquid-phase vapor pressures (PL, Pa), Henry's law constants (H, Pa m3 mol−1) or octanol-air partition coefficients (KOA) imply local air-surface exchange, whereas more shallow slopes reflect a greater contribution from distant transport [45,46]. Physicochemical properties for compounds examined here and two POPs of similar molecular mass (pentachlorobenzene and hexachlorobenzene) are given in Table S6.

The CC data analysis is summarized in Table S7, where apparent enthalpies of surface-air exchange (ΔSAH (kJ mol−1) = ‒slope × R × 2.303/1000) are compared to enthalpies of liquid-phase vapor pressure (ΔVAPH), Henry's law constant (ΔWAH), and octanol-air partition coefficient (ΔOAH). The ΔWAH of TriBA was within ±1 SD of its apparent ΔSAH at Råö, whereas the ΔWAH of DiBA was outside the ±2 SD limit, implying local exchange of TriBA and more distant (over the open ocean) transport of DiBA. The difference between the two BAs may relate to the enrichment of TriBA in macroalgae along the Swedish and Norwegian coasts, in which the fraction TriBA/(TriBA + DiBA) is 0.75 ± 0.15 [15].

Temperature-dependent properties for DAME and TeCV have not been reported. Their apparent ΔSAH values were compared to thermodynamically consistent “final adjusted values” (FAVs) ΔVAPH, ΔWAH, and ΔOAH for pentachlorobenzene and hexachlorobenzene (Shen and Wania, 2005) (Table S6). One or more of the FAVs were within ±1 SD of apparent ΔSAH values of DAME and TeCV at Råö (Table S7). Thus, local exchange likely controls or modifies atmospheric concentrations of these compounds. Being a coastal station, Råö receives land and sea breezes and is influenced by both terrestrial and marine exchange processes. Similar comparisons at Pallas show distant transport influence for both BAs (FAVs outside ±2 SD limits of apparent ΔSAH) and local control or influence for DAME and TeCV (FAVs within ±1 or ±2 SD of apparent ΔSAH) (Table S7). Local exchange for DAME and TeCV at both sites implies terrestrial and marine sources. For DAME, terrestrial sources could be fungi (Section 3.4), while marine sources might involve sea-to-air exchange. DAME has been reported over the open ocean by [9,10]; who showed close coupling between air and water concentrations, and we found DAME in Baltic estuaries [47].

Our previous study examined air parcel trajectories for the two air monitoring sites [5]. Transport directions at Råö were mainly from the NW-SW, off the open ocean, and less frequently from the land sectors. Pathways were more variable at Pallas and showed no prevailing direction. Significant ΔSAH values for DAME and TeCV at Råö, where air transport off the ocean is common, support our above statement that sea-to-air exchange and terrestrial fungi might be supplying these compounds to the atmosphere.

No significant temporal trends were evident for any compound over 2002–2019. Earlier, we noted a weakly significant (p = 0.041) increase in DiBA at Pallas between 2002 and 2015, but no trends for TriBA at Pallas nor for either BA at Råö [5]. The addition of 2018–2019 data resulted in no significant trends (p > 0.05) at either site.

3.3. HMBs in precipitation

Rain and snow meltwater were processed by draining through a GFF-PUF trap, and the water volume was not measured. Bulk precipitation fluxes (pg m−2 d−1) of particulate and gaseous species were determined by analysis of the GFF-PUF trap, and concentrations (pg L−1) were estimated from precipitation volumes measured at a nearby station, as in our previous study [5]. Annually averaged precipitation concentrations and fluxes of BAs, DAME, and TeCV at Råö (2014, 2018, and 2019) and Pallas (2018 and 2019) are summarized in Table 2. BAs in precipitation from 2002 to 2015 have been reported previously [5]; Råö 2014 is repeated here because the chlorinated HMBs were also determined for that year. PeCA was generally below the detection limit in precipitation and not reported.

Table 2.

Halomethoxybenzenes in precipitation, Råö (2014, 2018, and 2019) and Pallas (2018 and 2019).

|

Råö |

Concentration (pg L−1)a |

Flux (pg m−2 d−1)a |

Scavenging ratio, SRb |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 | DiBA | TriBA | DAME | TeCV | DiBA | TriBA | DAME | TeCV | DiBA | TriBA | DAME | TeCV |

| Mean | 41 | 44 | 241 | 52 | 80 | 84 | 450 | 115 | 1289 | 862 | 1964 | 1659 |

| SD | 19 | 18 | 138 | 31 | 34 | 26 | 195 | 137 | 415 | 465 | 435 | 459 |

| Geomean | 37 | 41 | 213 | 44 | 72 | 80 | 416 | 84 | 1226 | 758 | 1915 | 1608 |

| N | 11 | 11 | 12 | 12 | 11 | 11 | 12 | 12 | 10 | 10 | 7 | 7 |

| 2018 | DiBA | TriBA | DAME | TeCV | DiBA | TriBA | DAME | TeCV | DiBA | TriBA | DAME | TeCV |

| Mean | 21 | 43 | 52 | 30 | 23 | 44 | 54 | 27 | 935 | 1561 | 2235 | 2481 |

| SD | 14 | 30 | 35 | 22 | 18 | 32 | 27 | 14 | 1012 | 2169 | 3455 | 2611 |

| Geomean | 17 | 33 | 43 | 22 | 18 | 36 | 46 | 24 | 519 | 806 | 1190 | 1666 |

| N | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 |

| 2019 | DiBA | TriBA | DAME | TeCV | DiBA | TriBA | DAME | TeCV | DiBA | TriBA | DAME | TeCV |

| Mean | 18 | 29 | 22 | 14 | 46 | 59 | 45 | 28 | 658 | 1183 | 997 | 2842 |

| SD | 11 | 20 | 24 | 11 | 26 | 45 | 54 | 25 | 318 | 1273 | 1119 | 4935 |

| Geomean | 12 | 22 | 15 | 11 | 39 | 46 | 26 | 20 | 581 | 773 | 627 | 1371 |

| N | 7 | 9 | 12 | 10 | 8 | 9 | 12 | 10 | 6 | 9 | 12 | 10 |

| Pallas | Concentration (pg L−1) | Flux (pg m−2 d−1) | Scavenging ratio, SR | |||||||||

| 2018 | DiBA | TriBA | DAME | TeCV | DiBA | TriBA | DAME | TeCV | DiBA | TriBA | DAME | TeCV |

| Mean | 24 | 19 | 93 | 8.1 | 43 | 29 | 135 | 11 | 2253 | 2924 | 3425 | 4573 |

| SD | 23 | 12 | 66 | 4.4 | 47 | 22 | 128 | 4.2 | 1698 | 3079 | 3722 | 4235 |

| Geomean | 15 | 16 | 72 | 7.0 | 23 | 23 | 86 | 9.7 | 1756 | 1782 | 2100 | 3186 |

| N | 9 | 11 | 12 | 9 | 9 | 11 | 12 | 9 | 9 | 11 | 12 | 9 |

| 2019 | DiBA | TriBA | DAME | TeCV | DiBA | TriBA | DAME | TeCV | DiBA | TriBA | DAME | TeCV |

| Mean | 8.6 | 8.1 | 51 | 4.6 | 19 | 16 | 105 | 7.6 | 660 | 1690 | 3938 | 11632 |

| SD | 5.7 | 2.4 | 44 | 2.5 | 13 | 9.1 | 108 | 3.0 | 390 | 1428 | 3724 | 19737 |

| Geomean | 6.7 | 7.7 | 37 | 4.2 | 14 | 14 | 61 | 7.1 | 570 | 1376 | 2746 | 4968 |

| N | 8 | 11 | 12 | 10 | 8 | 11 | 12 | 10 | 7 | 10 | 12 | 10 |

Concentrations and fluxes were calculated with substitution of 1/2∗LOD for samples < LOD.

SR = (pg m−3)precip/(pg m−3)air, calculated for events with both precipitation and air > LOD.

Geometric mean (GM) fluxes of DiBA and TriBA at Råö in combined years 2018–2019 were 24 and 40 pg m−2 d−1. GM fluxes at Råö of 68 and 60 pg m−2 d−1 were reported for the two BAs in 2012, 2014, and 2015 [5]. The lower fluxes in 2018–2019 might be due partly to reduced monthly precipitation in these years (4.9 ± 2.5 cm) compared to 7.0 ± 3.2 cm in the earlier years. GM fluxes of DiBA and TriBA at Pallas in 2018–2019 were 18 and 18 pg m−2 d−1, while 41 pg m−2 d−1 for DiBA and 33 pg m−2 d−1 for TriBA were reported for combined 2012–2015 [5]. Monthly precipitation at Pallas in 2018–2019 (4.9 ± 2.9 cm) was only slightly lower than in 2012 and 2015 (5.6 ± 2.6 cm) and unlikely to account for the lower fluxes in recent years. GM fluxes of DAME and TeCV at Råö (2018–2019) were 34 and 22 pg m−2 d−1 and at Pallas (2018–2019) 73 and 8.2 pg m−2 d−1.

Scavenging ratios (SR = (pg m−3)precip/(pg m−3)air) were estimated from monthly precipitation and air concentrations. GM SRs of DiBA and TriBA at Råö in 2018–2019 were 540 and 791 and at Pallas 1052 and 1650. In our earlier study [5], GM SRs for DiBA and TriBA were 1140 and 642 at Råö, and 1760 and 1490 at Pallas. Precipitation scavenging of gaseous compounds increases at lower temperatures due to greater Henry's law partitioning into rain (SR = RT/H) and sorption to snow surfaces [48,49]. This is shown by the significant (p < 0.0001) trend of log SR versus 1/T (K) for the combined Råö-Pallas TriBA data set in 2018–2019 (Fig. 6) and also in our earlier study [5]. In both data sets, the SRs of DiBA were also suggestive of an increasing trend at lower temperatures, but the regressions were not significant. The trendline for TriBA agrees well with the theoretical log SR versus 1/T, estimated from its Henry's law constant (Table S6).

Fig. 6.

a, Scavenging ratios (SR) for BAs, combined Råö and Pallas data sets for 2018 and 2019. TriBA: y = 1613× ‒ 2.846, R2 = 0.218, p = 1.6 × 10−5. DiBA: regression not significant, p = 0.091). The solid red line shows the regression for measured SR of TriBA, dashed lines show theoretical SRs of DiBA and TriBA, based on their reported Henry's law constants (H) (Table S6), where SR = RT/H. b, SRs for DAME and TeCV, combined Råö and Pallas data sets for 2018 and 2019. DAME: y = 1400× ‒ 1.791, R2 = 0.130, p = 0.007. TeCV: y = 2102× ‒ 4.069, R2 = 0.229, p = 0.0006). The solid red line shows the regression for measured SRs, dashed lines show theoretical SRs, based on estimated H (Table S6, assuming the same H value for DAME and TeCV).

GM SRs at Råö (2014, 2018, and 2019) were 1219 for DAME and 1623 for TeCV, and 2543 for DAME and 4503 for TeCV at Pallas. Regressions of log SR versus 1/T (K) for the combined data sets were significant for both species, p = 0.007 for DAME and p = 0.0006 for TeCV (Fig. 6). Theoretical SRs for gas-phase DAME and TeCV were assumed to be the same and were estimated from Henry's law constant of TeCV at 25 °C and the estimated CC slope for Henry's law constant of hexachlorobenzene (Table S6). Fig. 6 shows that measured SRs tend to be about a factor of 3 or less above the theoretical estimates, which assume only gaseous dissolution into precipitation. Elevated SRs can result from the scavenging of particulate species, surface adsorption at the air-water interface [49] and on snow crystals [48].

3.4. HMBs in terrestrial fungi and forest litter

Fruiting bodies of terrestrial fungi (19) and litter/humus samples (6) were screened for DAME and TeCV. Our method has a limit of detection (LOD, see SM) of about 0.0015 mg kg−1. DAME in four species ranged from 0.8 to 3.7 mg kg−1 fresh weight (fw): Micromphale perforans (a saprotroph), Stereum hirsutum (a white rot), Thelephora terrestris (an ectomycorrhiza), and Hydnellum mirabile (an ectomycorrhiza). Three others, i.e., Stereum subtomentosum (a white rot), Cladonia stellaris (a lichen), and Jackrogersella multiformis (a soft rot, intermediate between white and brown rot), contained 0.011–0.049 mg kg−1 fw. The litter/humus samples, presumably permeated with fungal mycelia, contained 0.006–1.5 mg kg−1 fw. Thus, in accordance with earlier work [20,34], we found DAME in fungi representing a range of nutritional strategies. Only a few samples contained detectable levels of TeCV, 0.0033 and 0.042 mg kg−1 in M. perforans and T. terrestris, respectively, and 0.0033–0.016 mg kg−1 in litter/humus (n = 3). The general lack of TeCV in fungi and litter is surprising, given its abundance in air and precipitation; however, we note that the number of fungal species screened here is small compared to their diversity. BAs and PeCA were not detected in fungi nor litter/humus.

4. Conclusions

This study adds to the growing body of knowledge concerning natural halogenated compounds in the air and deposition and is the first report of DAME in Arctic air. BAs follow the previously established trend of higher levels near the coast (Råö) versus inland (Pallas), in agreement with the known production of BAs in the marine environment. Local versus distant sources of TriBA versus DiBA at Råö may be related to the high proportion of TriBA/DiBA in coastal macroalgae. Inferred local sources of DAME at the two sites suggest volatilization from the terrestrial environment. In support of this, DAME was quantified in several species of fungi and forest litter. Sea-air exchange may also contribute at Råö since DAME has been reported in seawater. DAME in air showed negative or no correlation with Σ12PAHs, in apparent contradiction to a hypothesis that biomass burning would release DAME into the atmosphere [33]. However, this hypothesis is not refuted, as biomass burning may not be the main source of PAHs at our sites. TeCV has been associated with the pulp and paper industry, but its close association with DAME in this study also suggests natural sources. PeCA was found in the air at levels lower than reported in the past, and we can report nothing further about its sources now. Deposition of HMBs by rain and snowfall increased at colder temperatures and was reasonably described by gas-phase scavenging according to Henry's Law.

Funding sources

This study was financed by the Swedish strategic research program ECOCHANGE for the Baltic Sea from the Swedish Research Council Formas.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: Terry Bidleman reports equipment, drugs, or supplies was provided by IVL Swedish Environmental Research Institute.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ese.2022.100209.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Führer U., Diessler A., Schreitmüller J., Ballschmiter K. Analysis of halogenated methoxybenzenes and hexachlorobenzene (HCB) in the picogram m-3 range in marine air. Chromatographia. 1997;45:414–427. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Führer U., Ballschiter K. Bromochloromethoxybenzenes in the marine troposphere of the Atlantic Ocean: a group of organohalogens with mixed biogenic and anthropogenic origin. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1998;32:2208–2215. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arinaitwe K., Kiremire B.T., Muir D.C.G., Fellin P., Li H., Teixeira C., Mubiru D.N. Legacy and currently used pesticides in the atmospheric environment of Lake Victoria, East Africa. Sci. Total Environ. 2016;543:9–18. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.10.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Atlas E., Sullivan K., Giam C.S. Widespread occurrence of polyhalogenated aromatic ethers in the marine atmosphere. Atmos. Environ. 1986;20:1217–1220. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bidleman T.F., Brorström ‒ Lundén E., Hansson K., Laudon H., Nygren O., Tysklind M. Atmospheric transport and deposition of bromoanisoles along a temperate to Arctic gradient. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017;51:10974–10982. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.7b03218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bidleman T.F., Laudon H., Nygren O., Svanberg S., Tysklind M. Chlorinated pesticides and natural brominated anisoles in air at three northern Baltic stations. Environ. Pollut. 2017;225:381–389. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2017.02.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bidleman T.F., Andersson A., Haglund P., Tysklind M. Will climate change influence production and environmental pathways of halogenated natural products? Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020;54:6468–6485. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.9b07709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hung H., Blanchard P., Halsall C.J., Bidleman T.F., Stern G.A., Fellin P., Muir D.C.G., Barrie L.A., Jantunen L.M., Helm P.A., Ma J., Konoplev A. Temporal and spatial variabilities of atmospheric POPs in the Canadian Arctic: results from a decade of monitoring. Sci. Total Environ. 2005;342:119–144. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2004.12.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schreitmüller J., Ballschmiter K. The equilibrium distribution of semivolatile organochloro ‒ compounds between atmosphere and surface water in the Atlantic Ocean. Angew. Chem. Int. Eng. Ed. 1994;33:646–649. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schreitmüller J., Ballschmiter K. Air-water equilibrium of hexachlorocyclohexanes and chloromethoxybenzenes in the north and South Atlantic. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1995;29:207–215. doi: 10.1021/es00001a027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Su Y., Hung H., Blanchard P., Patton G.W., Kallenborn R., Konoplev A., Fellin P., Li H., Geen C., Stern G., Rosenberg B., Barrie L.A. A circumpolar perspective of atmospheric organochlorine pesticides (OCPs): results from six Arctic monitoring stations in 2000–2003. Atmos. Environ. 2008;42:4682–4698. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wittlinger R., Ballschmiter K. Studies of the global baseline pollution XlII. C6-C14 organohalogens (α- and γ-HCH, HCB, PCB, 4,4'-DDT, 4,4'-DDE, cis- and trans- chlordane, trans-nonachlor, anisols) in the lower troposphere of the southern Indian Ocean. Fresen. J. Anal. Chem. 1990;336:193–200. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wong F., Jantunen L.M., Pućko M., Papakyriakou T., Stern G.A., Bidleman T.F. Air ‒ water exchange of anthropogenic and natural organohalogens on International Polar Year (IPY) expeditions in the Canadian Arctic. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011;45:876–881. doi: 10.1021/es1018509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Agarwal V., El Gamal A.A., Yamanaka K., Poth D., Kersten R.D., Schorn M., Allen E.E., Moore B.S. Biosynthesis of polybrominated aromatic organic compounds by marine bacteria. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2014;10:640–647. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bidleman T.F., Andersson A., Brugel S., Ericson L., Haglund P., Kupryianchyk D., Lau D.C.P., Liljelind P., Lundin L., Tysklind A., Tysklind M. Bromoanisoles and methoxylated bromodiphenyl ethers in macroalgae from Nordic coastal regions. Environ. Sci. Proc. Impacts. 2019;21:881–892. doi: 10.1039/c9em00042a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Busch J., Agarwal V., Schorn M., Machado H., Moore B.S., Rouse G.W., Gram L., Jensen P.R. Diversity and distribution of the bmp gene cluster and its polybrominated products in the genus Pseudoalteromonas. Environ. Microbiol. 2019;21:1575–1585. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.14532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Michałowicz J., Włuka A., Bukowska B. A review on environmental occurrence, toxic effects and transformation of man-made bromophenols. Sci. Total Environ. 2022;811 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.152289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Howe P.D., Dobson S., Malcolm H.M. Concise International Chemical Assessment Document. Vol. 6. World Health Organisation; Geneva: 2005. 2,4,6-Tribromophenol and other simple bromophenols; p. 47. 92 4 1560066 9. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Allard A.-S., Remberger M., Neilson A. Bacterial O-methylation of halogen-substituted phenols. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1987;53:839–845. doi: 10.1128/aem.53.4.839-845.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.deJong E., Field J.A. Sulfur tuft and Turkey tail: biosynthesis and biodegradation of organohalogens by Basidiomycetes. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 1997;51:375–414. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.51.1.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Winterton N. Chlorine: the only green element – towards a wider acceptance of its role in natural cycles. Green Chem. 2000;2:173–225. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ortiz-Bermúdez P., Hirth K.C., Srebotnik E., Hammel K.E. Chlorination of lignin by ubiquitous fungi has a likely role in global organochlorine production. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:3895–3900. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610074104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Faroon O., Ingerman L., Custodio Muianga C., Citra M. Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR), U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services; Atlanta, GA: 2021. Toxicological Profile for Pentachlorophenol, Draft for Public Comment; p. 158. pp + appendices. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kirchner M., Jakobi G., Körner W., Levy W., Moche W., Niedermoser B., Schaub M., Ries R., Weiss P., Antritter F., Fischer N., Henkelmann B., Schramm K.-W. Ambient air levels of organochlorine pesticides at three high alpine monitoring stations: trends and dependencies on geographical origin. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 2016;16:738–751. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wong F., Hung H., Dryfhout-Clark H., Aas W., Bohlin-Nizzetto P., Breivik K., Mastromonaco M.N., Brorström Lundén E., Ólafsdóttir K., Sigurðsson Á., Vorkamp K., Bossi R., Skov H., Hakola H., Barresi E., Sverko E., Fellin P., Li H., Vlasenko A., Zapevalov M., Samsonov D., Wilson S. Time trends of persistent organic pollutants (POPs) and Chemicals of Emerging Arctic Concern (CEAC) in Arctic air from 25 years of monitoring. Sci. Total Environ. 2021;775 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.145109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kylin H., Svensson T., Jensen S., Strachan W.M.J., Franich R., Bouwman H. The trans ‒ continental distributions of pentachlorophenol and pentachloroanisole in pine needles indicate separate origins. Environ. Pollut. 2017;229:688–695. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2017.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Diaz A., Fabrellas C., Ventura F., Galceran M.T. Determination of the odor threshold concentrations of chlorobrominated anisoles in water. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005;53:383–387. doi: 10.1021/jf049582k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alañón M.E., Alarcón M., Díaz-Maroto I.J., Pérez-Coello M.S., Díaz-Maroto M.C. Corky off-flavor compounds in cork planks at different storage times before processing. Influence on the quality of the final stopper. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2020;101:4735–4742. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.11119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Álvarez-Rodríguez M.L., López-Ocaña L., López-Coronado J.M., Rodríguez E., Martínez M.J., Larriba G., Coque J.-J.R. Cork taint of wines: role of the filamentous fungi isolated from cork in the formation of 2,4,6-trichloroanisole by O-methylation of 2,4,6-trichlorophenol. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2002;68:5860–5869. doi: 10.1128/AEM.68.12.5860-5869.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Whitfield F.B., Hill J.L., Shaw K.J. 2,4,6-Tribromoanisole: a potential cause of mustiness in packaged food. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1997;45:889–893. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brownlee B.G., Macinnis G.A., Noton L.R. Chlorinated anisoles and veratroles in a Canadian river receiving bleached kraft pulp mill effluent. Identification, distribution, and olfactory evaluation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1993;27:2450–2455. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Neilson A.H., Allard A.-S., Reiland S., Remberger M., Tärnholm A., Viktor T., Landner L. Tri- and tetrachloroveratrole, metabolites produced by bacterial O-methylation of tri- and tetrachloroguaiacol: an assessment of their bioconcentration potential and their effects on fish reproduction. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 1984;41:1502–1512. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Garvie L.A.J., Wilkins B., Groy P.L., Glaeser J.A. Substantial production of drosophilin A methyl ether (tetrachloro-1,4-dimethoxybenzene) by the lignicolous basidiomycete Phellinus badius in the heartwood of mesquite (Prosopis juliflora) trees. Sci. Nat. 2015;102:18. doi: 10.1007/s00114-015-1268-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Teuissen P.J.M., Swarts H.J., Field J.A. The de novo production of drosophilin A (tetrachloro-4-methoxyphenol) and drosophilin A methyl ether (tetrachloro-1,4 -dimethoxybenzene) by ligninolytic basidiomycetes. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1997;47:695–700. doi: 10.1007/s002530050997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Milliken C.E., Meier G.P., Watts J.E.M., Sowers K.E., May H.D. Microbial anaerobic demethylation and dechlorination of chlorinated hydroquinone metabolites synthesized by basidiomycete fungi. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2004;70:385–392. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.1.385-392.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Riquelme C., Candia B., Ruiz D., Herrera M., Becerra J., Pérez C., Rajchenberg M., Cabrera-Pardo J.R. The de novo production of halogenated hydroquinone metabolites by the Andean-Patagonian white-rot fungus Phylloporia boldo. Curr. Res. Environ. Appl. Mycol. 2020;10:198–205. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hiebl J., Lehnert K., Vetter W. Identification of a fungi-derived terrestrial halogenated natural product in wild boar (Sus scrofa) J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011;59:6199. doi: 10.1021/jf201128r. 6192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kavanaugh F., Hervey A., Robbins W.J. Antibiotic substances from basidiomycetes IX. Drosophila subartrata. Proc. U.S. Nat. Acad. Sci. 1952;38:555–560. doi: 10.1073/pnas.38.7.555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Röhler L., Schlabach M., Haglund P., Breivik K., Kallenborn R., Bohlin-Nizzetto P. Non ‒ target and suspect characterisation of organic contaminants in Arctic air – Part 2: Application of a new tool for identification and prioritisation of chemicals of emerging Arctic concern in air. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2020;20:9031–9049. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mazur D.M., Polyakova O.V., Artaev V.B., Lebedev A.T. Novel pollutants in the Moscow atmosphere in winter period: gas chromatography-high resolution time-of-flight mass spectrometry study. Environ. Pollut. 2017;222:240–250. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2016.12.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bidleman T.F., Agosta K., Andersson A., Haglund P., Hegmans A., Liljelind P., Jantunen L.M., Nygren O., Poole J., Ripszam M., Tysklind M. Sea-air exchange of bromoanisoles and methoxylated bromodiphenyl ethers in the Northern Baltic. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2016;112:58–64. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2016.08.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Anttila P., Brorström-Lundén E., Hansson K., Hakola H., Vestenius M. Assessment of the spatial and temporal distribution of persistent organic pollutants (POPs) in the Nordic atmosphere. Atmos. Environ. 2016;140:22–33. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bidleman T.F., Tysklind M. Breakthrough during air sampling with polyurethane foam: what do PUF 2/PUF 1 ratios mean? Chemosphere. 2018;192:267–271. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2017.10.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Luo J., Han Y., Zhao Y., Huang Y., Liu X., Tao S., Liu J., Huang T., Wang L., Chen K., Ma J. Effect of northern boreal forest fires on PAH fluctuations across the Arctic. Environ. Pollut. 2020;261 doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2020.114186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hoff R.M., Brice K.A., Halsall C.J. Nonlinearity in the slopes of Clausius-Clapeyron plots for SVOCs. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1998;32:1793–1798. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wania F., Haugen J.-E., Lei Y.D., Mackay D. Temperature dependence of atmospheric concentrations of semivolatile organic compounds. Environ. Sci. Technol. 1998;32:1013–1021. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bidleman T.F., Agosta K., Andersson A., Brugel S., Ericson L., Hansson K., Tysklind M. 2022. Sources and Pathways of Halogenated Natural Products in Northern Baltic Estuaries. Submitted. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lei Y.D., Wania F. Is rain or snow a more efficient scavenger of organic chemicals? Atmos. Environ. 2004;38:3557–3575. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Simcik M.F. The importance of surface adsorption on the washout of semivolatile organic compounds by rain. Atmos. Environ. 2004;38:491–501. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.