Abstract

Background

Measurement of serum concentrations of drugs is a novelty found useful in detecting poor drug adherence in patients taking ≥2 antihypertensive agents. Regarding patients with treatment‐resistant hypertension, we previously based our assessment on directly observed therapy. The present study aimed to investigate whether serum drug measurements in patients with resistant hypertension offer additional information regarding drug adherence, beyond that of initial assessment with directly observed therapy.

Methods and Results

Nineteen patients assumed to have true treatment‐resistant hypertension and adherence to antihypertensive drugs based on directly observed therapy were investigated repeatedly through 7 years. Serum concentrations of antihypertensive drugs were measured by ultra‐high‐performance liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry from blood samples taken at baseline, 6‐month, 3‐year, and 7‐year visits. Cytochrome P450 polymorphisms, self‐reported adherence and beliefs about medicine were performed as supplement investigations. Seven patients (37%) were redefined as nonadherent based on their serum concentrations during follow‐up. All patients reported high adherence to medications. Nonadherent patients expressed lower necessity and higher concerns regarding intake of antihypertensive medication (P=0.003). Cytochrome P450 polymorphisms affecting metabolism of antihypertensive drugs were found in 16 patients (84%), 21% were poor metabolizers, and none were ultra‐rapid metabolizers. Six of 7 patients redefined as nonadherent had cytochrome P450 polymorphisms, however, not explaining the low serum drug concentrations measured in these patients.

Conclusions

Our data suggest that repeated measurements of serum concentrations of antihypertensive drugs revealed nonadherence in one‐third of patients previously evaluated as adherent and treatment resistant by directly observed therapy, thereby improving the accuracy of adherence evaluation.

Registration

URL: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov; unique identifier: NCT01673516.

Keywords: antihypertensive drugs, blood pressure, directly observed therapy, nonadherence, resistant hypertension, serum drug concentrations

Subject Categories: Hypertension

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- ABPM

ambulatory blood pressure measurement

- BMQ

Beliefs About Medicines Questionnaire

- CYP

cytochrome P450

- DOT

directly observed therapy

- IM

intermediate metabolizer

- Oslo RDN

Oslo Renal Denervation study

- PM

poor metabolizer

- RDN

renal denervation

Clinical Perspective.

What Is New?

We investigated adherence over 7 years with serum measurements of antihypertensive agents in patients unaware of drug testing.

Nonadherence revealed in 7 of 19 patients (37%) prescribed ≥3 antihypertensive agents recruited for renal denervation and at the outset considered true treatment resistant by directly observed therapy.

Though they reported high adherence, nonadherent patients expressed lower necessity and higher concerns regarding intake of antihypertensive medication (P=0.003).

Cytochrome P450 polymorphisms affecting metabolism of antihypertensive drugs were found in 16 patients (84%), 21% were poor metabolizers, and none were ultra‐rapid metabolizers; hence, cytochrome P450 polymorphisms could not explain the low serum concentrations.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

Nonadherence to drugs is one of the main problems in the treatment of patients with hypertension and contributes to poor blood pressure control, which is associated with increased morbidity and mortality.

Increased knowledge of mechanisms explaining nonadherence to antihypertensive drugs is crucial to improve adherence to antihypertensive drugs in the many patients with hypertension.

Poor adherence to antihypertensive medications is estimated to be present in 5% to 85% of patients with apparent treatment‐resistant hypertension. 1 , 2 , 3 Detecting nonadherence is challenging for many reasons, and the large differences in prevalence may be attributable to the diversity of methods used, the sensitivity and accuracy of these methods, and the heterogeneity of study populations. Indirect methods (eg, self‐reports and prescription rates) seem to underestimate the prevalence of nonadherence compared with direct methods like witnessed intake of antihypertensive medication (directly observed therapy [DOT]) followed by 24‐hour ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM) or measurements of antihypertensive drugs in body fluids. 3 In individuals who previously had uncontrolled blood pressure (BP), normalization of BP after DOT may indicate nonadherence 4 , 5 ; however, some antihypertensive drugs require regular intake over a certain period of time to have maximal effect. Patients not taking these drugs may be falsely considered adherent if BP remains elevated after DOT. Measurements of serum drug concentrations have been introduced as a promising, easy‐to‐do, and cost‐effective method for objectively evaluating adherence and may mitigate the challenge of patients changing their intake of medications in randomized trials and patients not responding or being insufficiently treated with antihypertensive drugs. 6 , 7 , 8 Despite the need for laboratory facilities, instruments, and technicians, the improvement in sensitivity of detecting nonadherence and ultimately improving clinical outcome may be worthwhile. Drug intake but also pharmacokinetic variation in absorption, distribution, metabolism, and elimination and factors influencing these processes such as drug interactions, diseases, and genetics may influence serum concentrations. Pharmacodynamic causes cannot be ruled out. Mutations in cytochrome P450 (CYP) genes can lead to altered CYP enzyme activity and thereby rate of drug clearance and lead to suboptimal effect or more pronounced side effects. 9 For cardiovascular drugs, mutations in CYP genes often lead to loss of function, which leads to suboptimal metabolism and increased serum concentrations.

Thus, based on this emerging knowledge of drug adherence in hypertension, the aim of the present study was to investigate whether measurements of serum concentrations of antihypertensive drugs offer additional information regarding drug adherence, beyond the status of assumed drug adherence documented by initial assessment with DOT. Because adherence is not a static trait but may vary over time in an individual, we aimed to assess adherence to antihypertensive drugs using repeated serum drug measurements during a preplanned 7‐year clinical follow‐up of patients with apparent true treatment‐resistant hypertension. CYP polymorphisms, self‐reported adherence, and beliefs about principles of preventive medicine were additionally investigated to further explore factors related to interpretation of adherence.

METHODS

Study Participants and Approvals

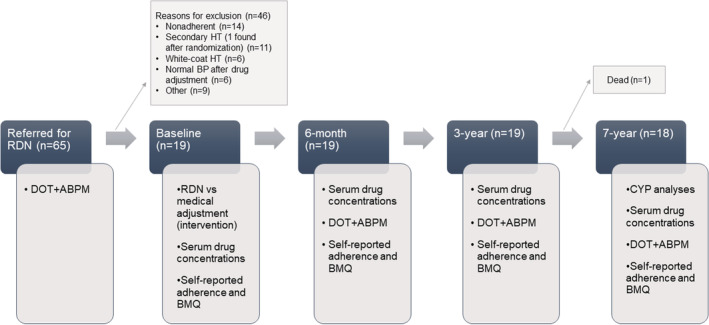

The data that support the findings of the present study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. In 2012 to 2013, patients (n=19) assumed to have true treatment‐resistant hypertension were included in the Oslo RDN (Oslo Renal Denervation study) at Oslo University Hospital, Oslo, Norway. Patients (n=65) with ABPM ≥135 mm Hg despite optimal doses of at least 3 antihypertensive agents including a diuretic were referred specifically for renal denervation (RDN) from hospitals and specialist practices in Norway, and further thorough investigations excluded not‐yet‐detected white‐coat hypertension, secondary causes of hypertension, and poor drug adherence before inclusion. Apart from clinical examination and biochemical screening, all patients underwent computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging of renal arteries. If daytime systolic ABPM remained ≥135 mm Hg after witnessed intake of the morning drugs (DOT), patients were assumed to be adherent. 4 Complete inclusion criteria and baseline characteristics have previously been described. 10 The average age was 60 (±8.7) years and 89.5% were men (Table). Eighteen patients were White, and one was from the Middle East. The patients were randomly assigned to RDN treatment (n=9) or to further improvements of the antihypertensive drug regimens guided by thoracic impedance hemodynamic measurements (control group, n=10). The protocol included 10 years of follow‐up, and 7‐year follow‐up of BP data has been published 11 (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Patients Defined as Nonadherent and Adherent Based on Serum Concentrations of Antihypertensive Drugs

| Variables | Nonadherent (n=7) | Adherent (n=12) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Renal denervation, % (n) | 57.1 (4) | 41.7 (5) | 0.65 |

| Age, y | 54.7 (±10.1) | 63.1 (±6.2) | 0.038 |

| Male, % (n) | 71.4 (5) | 100 (12) | 0.12 |

| Systolic daytime ABPM, mm Hg | 158 (±9.1) | 149 (±10.4) | 0.06 |

| Diastolic daytime ABPM, mm Hg | 94 (±8) | 88 (±8) | 0.14 |

| Heart rate, beats/min | 70 (±14) | 62 (±12) | 0.20 |

| No. of drugs | |||

| Antihypertensive agents* | 5 (5‐6) | 5 (4‐6.8) | 0.71 |

| Total number of prescribed agents | 8.4 (±2.5) | 7.3 (±2.1) | 0.35 |

| Total number of prescribed daily pills | 9 (±2.9) | 7.5 (±3.4) | 0.35 |

| Antihypertensive medication, % (n) | |||

| ACE inhibitors | 28.6 (2) | 33.3 (4) | N.a. |

| Angiotensin II receptor blockers | 85.7 (6) | 83.3 (10) | N.a. |

| Losartan (prodrug)† | 14.3 (1) | 16.7 (2) | N.a. |

| Calcium channel blockers‡ | 71.4 (5) | 83.3 (10) | N.a. |

| Diuretics§ | 85.7 (6) | 100 (12) | N.a. |

| Loop | 42.9 (3) | 33.3 (4) | N.a. |

| Thiazides | 71.4 (5) | 75 (9) | N.a. |

| Aldosterone antagonists | 57.1 (4) | 41.7 (5) | N.a. |

| Beta‐blockers | 71.4 (5) | 75 (9) | N.a. |

| α‐adrenoreceptor blockers | 28.6 (2) | 41.7 (5) | N.a. |

| Centrally acting sympatholytics | 71.4 (5) | 33.3 (4) | N.a. |

| Other§ | 14.3 (1) | 25 (3) | N.a. |

| Aliskiren | 14.3 (1) | 18.3 (1) | N.a. |

| Minoxidil | 0 | 16.7 (2) | N.a. |

| Body mass index, kg/m² | 29.2 (±4.5) | 30.1 (±5.7) | N.a. |

| eGFR (CKD‐EPI), ml/min per 1.73 m² | 89.1 (±13.3) | 88.2 (±5.8) | N.a. |

| Albuminuria, % (n) | 28.6 (2) | 41.7 (5) | N.a. |

| Left ventricular hypertrophy, % (n) | 57.1 (4) | 58.3 (7) | N.a. |

| Coronary heart disease, % (n) | 42.9 (3) | 33.3 (4) | N.a. |

| Peripheral arteriosclerosis, % (n) | 14.3 (1) | 0 (0) | N.a. |

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus, % (n) | 28.6 (2) | 25 (3) | N.a. |

| Hypercholesterolemia, % (n) | 42.9 (3) | 25 (3) | N.a. |

| Stroke/transient ischemic attack, % (n) | 0 (0) | 16.7 (2) | N.a. |

| Self‐reported adherence, visual analog (VAS) scale (0–100)* | 95 (83–99) | 100 (94–100) | 0.028 |

| Beliefs about Medicines Questionnaire (BMQ) | |||

| Necessity (Likert scale total score 5–25) | 17.7 (±2.1) | 21.0 (±3.4) | 0.035 |

| Concern (Likert scale total score 5–25) | 16.7 (±3.4) | 12.6 (±5.0) | 0.07 |

| Harm (Likert scale total score 4–20) | 11.1 (±2.8) | 9.1 (±3.5) | 0.21 |

| Overuse (Likert scale total score 4–20) | 12.1 (±2.3) | 10.3 (±3.3) | 0.22 |

| Necessity‐concern difference | 1 (±3.8) | 8.4 (±7.3) | 0.024 |

Categorical variables are given as percentages with absolute numbers in parentheses. Continuous variables are given as mean (±SD) or *median (IQR). ABPM indicates ambulatory blood pressure measurement. eGFR calculated by CKD‐EPI=Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration.

Losartan is metabolized by CYP enzymes (mainly CYP2C9) to a more active metabolite predominantly responsible for the angiotensin II receptor antagonism.

Only dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers were used.

Diuretics include loop diuretics and thiazides.

Other include aliskiren and minoxidil.

Figure 1. Flowchart showing number of patients and relevant procedures at the study visits.

ABPM indicates ambulatory blood pressure measurement; BMQ, Beliefs About Medicines Questionnaire; BP, blood pressure; CYP, cytochrome P450; DOT, directly observed treatment; HT, hypertension; and RDN, renal denervation.

All 19 patients signed the originally written consent form including bio‐banking of biological material at inclusion, as well as a new written consent form regarding the serum drug measurements at the 7‐year visit. Thus, the long‐time follow‐up study of these patients with assumed true treatment‐resistant hypertension was prospective and serum sampled and stored in accordance with the original protocol and ethical committee approval for bio‐banking. 10 The regional ethical committee specifically approved the present investigation of serum drug concentrations in retrospect. The protocol for the present study was developed and carried through in parallel with a much larger national study of the prevalence of nonadherence in patients being prescribed ≥2 antihypertensive drugs. 12

Measurement of BP

Twenty‐four‐hour ABPM was obtained by using a validated oscillometric device (Watch BP 03; Microlife, Cambridge, UK), in accordance with the European Society of Hypertension/European Society of Cardiology guidelines at the outset. 13 ABPM was recorded following DOT, which was performed immediately after collecting blood samples. DOT was performed at every visit to ensure comparable BP measurements, although DOT was used only once to assess adherence to the antihypertensive medication, namely, at the baseline visit as an inclusion criterion.

Blood Sample Collection

Patients were specifically instructed not to take their morning dose of antihypertensive medication before visits but to bring their antihypertensive medications to the hospital in original packages for the DOT procedure. The blood samples obtained before DOT should therefore represent a serum concentration ≈24 hours after the last ingested morning dose (the trough level).

Blood samples obtained at baseline and the 6‐month, 3‐year, and 7‐year visits (Figure 1) were stored at −80 °C until analyzed following the 7‐year visit.

Pharmacological Analyses

Concentrations of 25 commonly used antihypertensive drugs in serum samples were measured using ultra‐high‐performance liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (Agilent Technologies 6490 Triple Quad LC/MS; Matriks, Oslo, Norway). The results were interpreted and reported as adherent, partially nonadherent, or nonadherent, by an experienced pharmacologist (M.S.O.). The lowest calibrator of the calibration range (Table S1) was defined as the cutoff level for drug adherence, values at this level or higher were considered drug adherent, while values not detected by our method were considered nonadherent. Patients were defined as nonadherent if serum concentrations of none of the prescribed antihypertensive drugs were detected. In partially nonadherent patients, at least 1 of the prescribed antihypertensive drugs, but not all, was detected. For individually prescribed drugs, see Table S2.

Patients were further grouped as nonadherent or adherent based on their repeated measurements. Patients in the nonadherent group during the 7‐year observation time could be categorized as nonadherent or partially nonadherent at study visits during the time span. See Data S1.

Pharmacogenetic Analysis

Pharmacogenetic analyses were performed in whole blood using Taqman‐based real‐time polymerase chain reaction (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Walham, MA). Common CYP gene polymorphisms for CYP2D6, CYP2C9, CYP3A4, and CYP3A5 contributing to antihypertensive drug metabolism were examined.

Patients were classified into 4 phenotypically CYP2D6 groups on the basis of the consensus recommendations from the Clinical Pharmacogenetic Implementation Consortium and Dutch Pharmacogenetics Working Group 14 : poor metabolizers (PMs), intermediate metabolizers (IMs), normal metabolizers, and ultra‐rapid metabolizers. These analyses are further detailed in Data S1. When comparing serum concentrations in phenotypically different individuals, we aimed to correct for differences in dose by dividing serum concentrations by daily intake in milligrams.

Self‐Reported Adherence

At each visit, the patients evaluated their own adherence using a visual analog scale from 0 to 100, where 0 indicated no intake of prescribed medications at all, and 100 indicated intake of all prescribed medications without missing a dose, without a defined period of time. The visual analog scale is a validated and well‐known method for patient‐reported quality‐of‐life measures including adherence to therapy. 15 , 16 , 17

Beliefs About Medicines Questionnaire

The Beliefs About Medicines Questionnaire (BMQ) developed by Horne et al 18 was completed by the patients at every visit. The BMQ has been translated into Norwegian and validated in the Norwegian population. 19 , 20 , 21 It consists of various statements in regard to general and specific beliefs about medicines. The general beliefs are further divided into the subgroups “overuse” and “harm,” each consisting of 4 statements. The specific beliefs are divided into the subgroups “necessity” and “concern,” each containing 5 statements. 18 Answers are given on a 5‐point Likert scale, ranging from 1=“strongly disagree” to 5=“strongly agree.” Thus, the scores for overuse and harm range from 4 to 20, and for necessity and concern from 5 to 25. Nonadherence has previously been associated with a lower necessity and a higher concern score, 22 and to highlight this, a necessity–concern difference was calculated. A positive difference indicates that the patients believe the benefit of their antihypertensive medication outweighs the concern of taking them.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 26 (SPSS, Chicago, IL). P<0.05 (2‐sided) was considered statistically significant. All variables were tested by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test for normality before appropriate statistical methods were chosen. Continuous variables are presented as mean±SD or median±interquartile range as appropriate. Differences were tested by unpaired Student t test or Mann–Whitney U test depending on normal distribution or not. Because of the limited number of patients, nonadherent and partially nonadherent patients were treated as 1 group for statistical analyses. Categorical variables are presented as proportions, and differences between groups were tested by Fisher’s exact test because of the limited number of participants. Missing data regarding BMQ (0.3%) were replaced with the mean value of the entire study population for that particular question, so that scores and the necessity–concern difference could be calculated regardless of 1 missed question. Changes in mean BP, self‐reported adherence, and BMQ necessity–concern difference over time were tested by linear mixed models using individuals as a random factor and visits and adherence status as fixed‐effect covariates. Bivariate correlation coefficient (rho) was calculated using Spearman’s rank test.

RESULTS

Adherence Status by Serum Drug Concentrations

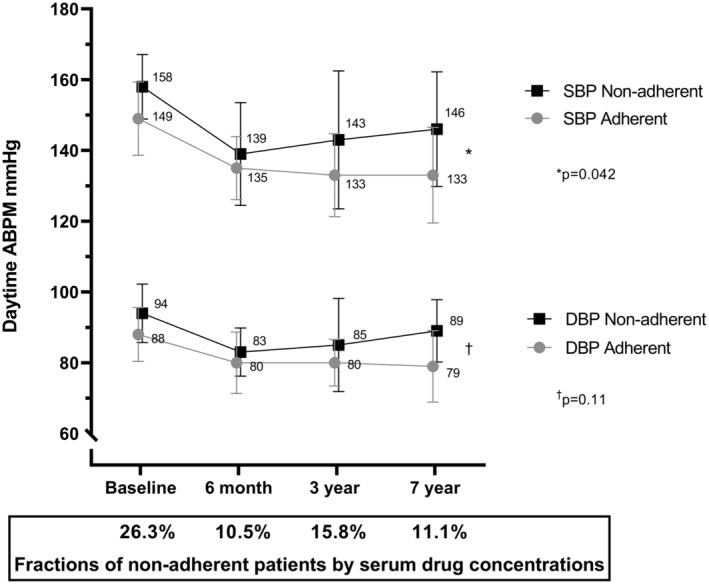

Seven of 19 patients (37%), all originally defined as adherent by DOT, were redefined as nonadherent or partially nonadherent based on their serum drug concentrations during the 7 years of follow‐up. One patient died between 3 and 7 years; the remaining patients attended all visits. Systolic and diastolic BPs and adherence status of the 7 nonadherent patients are shown in Figure 2. Systolic BPs measured repeatedly over 7 years were higher in the nonadherent group (P=0.042). Five patients (26%) had too‐low serum concentration of ≥1 drugs to be compatible with drug adherence at baseline. At the 6‐month, 3‐year, and 7‐year visits, 11%, 16%, and 11% of the patients, respectively, were nonadherent on the basis of serum concentrations. Nonadherence was not found to be more prevalent with certain classes of drugs, and prescribed calcium channel blockers, blockers of the renin‐angiotensin system, beta blockers, thiazides, and aldosterone antagonists were undetectable at similar rates (Table S2).

Figure 2. Mean daytime ambulatory blood pressure (ABPM) in the 7 patients who revealed nonadherence during follow‐up compared with the adherent patients (n=12).

SDs are marked with bars (±1 SD). The y axis is truncated. Generalized linear mixed models showed that daytime systolic ABPMs were significantly higher in the nonadherent patients (P=0.042) and diastolic ABPMs did not statistically differ between the groups (P=0.11). Fractions of nonadherent patients at the different visits on the x axis. DBP indicates diastolic blood pressure; and SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Four of the 7 patients who retrospectively were found to be nonadherent by serum drug measurements underwent an RDN procedure at the outset, while the remaining 3 had been randomized to drug adjustment in the original study. The nonadherent patients (n=7) were younger than the adherent patients (n=12) (P=0.038), and their systolic daytime ABPM at baseline tended to be higher (P=0.06). Comorbidities, kidney function, body mass index, and pill burden did not differ between the groups at baseline (Table).

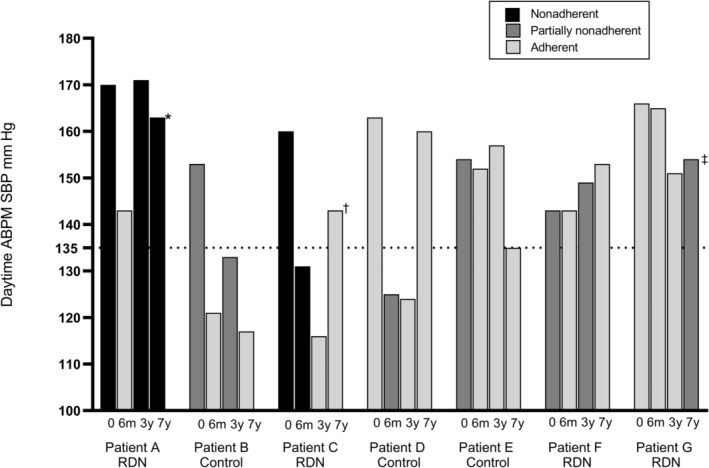

Of special interest is patient A, considered to be an RDN responder, nonadherent at baseline, but adherent to medication at the 6‐month visit, which may by itself explain the fall in BP. At the 3‐year visit, none of the 5 antihypertensive agents prescribed were detected, and the patient’s BP was again elevated. Serum drug measurements were not performed at the 7‐year visit for patient A since this patient eventually admitted complete nonadherence to all drugs. Patient C was also considered an RDN responder, an interpretation probably correct because the patient was nonadherent to all 10 antihypertensive drugs prescribed at both the baseline and the 6‐month visit. After 3 years, the BP was low, and patient C was adherent to the 2 antihypertensive drugs prescribed at that time (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Adherence over time in 7 patients defined as nonadherent on the basis of serum drug concentrations at ≥1 visits during 7‐year follow‐up.

The y axis shows the mean systolic daytime ambulatory blood pressure for each visit (0=baseline, 6m=6‐month visit, 3y=3‐year visit, 7y=7‐year visit). Light gray, dark gray, and black columns indicate the adherence status. *Refused to ingest any medications, and serum drug measurements were not performed. †Admitted nonadherence to 1 of 2 antihypertensive drugs, but a method to analyze this particular drug was not available. ‡Admitted to not having ingested antihypertensive medication during the past 48 hours, consistent with serum drug measurements (drugs with rapid elimination were below the detection limits). ABPM indicates ambulatory blood pressure measurement; RDN, renal denervation; and SBP, systolic blood pressure.

Self‐Reported Adherence and BMQ

Self‐reported adherence assessed by the visual analog scale was lower in the nonadherent patients at baseline (P=0.028, Table) but high in all patients. When taking the follow‐up visits (6‐month, 3‐year, and 7‐year) into account, there were no significant differences between the 2 groups (P=0.16).

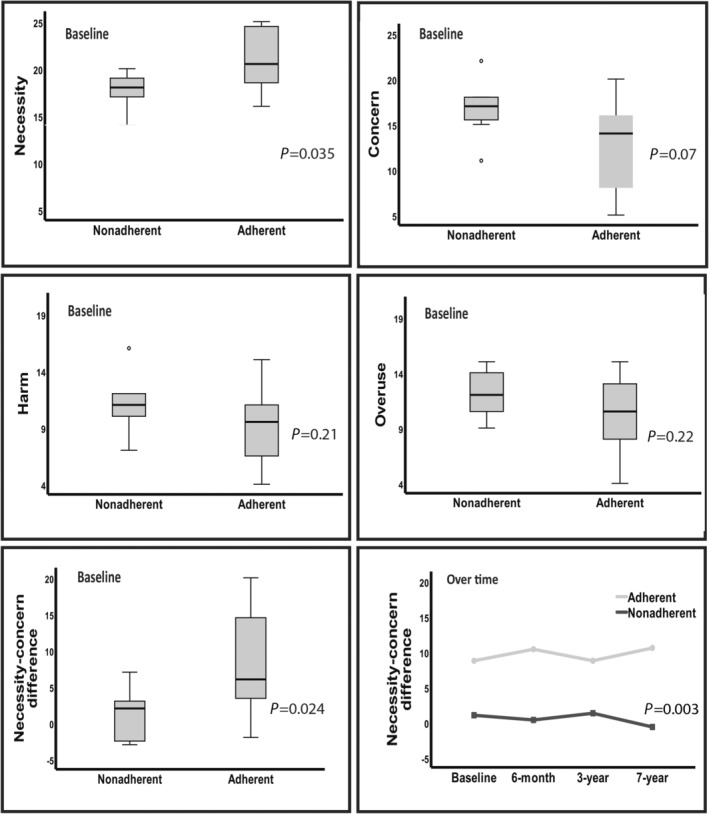

Nonadherent patients reported a significantly lower BMQ “necessity” score (P=0.035) and a tendency to have higher “concern,” resulting in a significantly lower necessity–concern difference at baseline (P=0.024) and over time (P=0.003) (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Difference in Beliefs About Medicines Questionnaire scores between nonadherent and adherent patients.

Results are reported as boxplots of all 4 dimensions at baseline and boxplot at baseline and change over time for the necessity–concern difference.

CYP Polymorphisms

Pharmacogenetic analyses were performed in all 18 patients attending the 7‐year visit, whereas the 19th patient (deceased) had these analyses performed earlier on clinical indication. CYP polymorphisms were detected in 16 of 19 patients (84%). Polymorphisms leading to absent (n=4; 21%) or severely reduced (n=5; 26%) metabolism were detected, and none had CYP polymorphisms leading to ultra‐rapid metabolism; hence, CYP polymorphisms could not explain the low serum concentrations in the nonadherent patients.

Of the 7 patients defined as nonadherent on the basis of serum drug concentrations, 6 had CYP polymorphisms associated with altered metabolism of antihypertensive drugs. Five were either CYP2D6 PMs or IMs; which mainly affects the metabolism of beta blockers, leading to increased serum concentrations. The frequencies of CYP2C9 and CYP3A4/3A5 polymorphisms were comparable with the European reference population. See Table S3 for further details. Metoprolol with prolonged release was the most common beta blocker in our population, used by 8 patients.

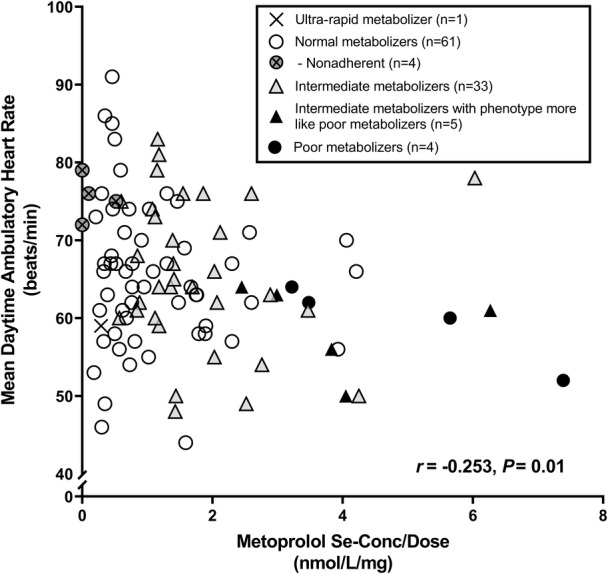

However, 8 patients taking metoprolol was too low a number to further investigate the consequence of being PMs. We therefore analyzed the relationships between CYP polymorphisms, serum concentrations of metoprolol, and the most typical clinical variable related to treatment with metoprolol, namely, heart rate. Figure 5 shows these data in 104 patients with hypertension participating in an ongoing cross‐sectional survey: 4 (3.8%) PMs, 5 (4.8%) IMs with phenotype more like PMs, 33 (31.7%) IMs, 61 (58.7%) normal metabolizers, and 1 (<1%) ultra‐rapid metabolizer. The relationship between serum concentration and mean daytime ambulatory heart rate was inverse and highly significant (r=−0.253; P=0.01). The PMs and IMs with phenotype more like PMs (n=9) tend to have high serum concentrations of metoprolol and daytime heart rate in the lower part of the distribution. Heart rate was 66±9 beats/min in normal metabolizers and IMs (n=94) and 59±5 beats/min in 4 PMs combined with 5 IMs with phenotype more like PMs (P=0.036). All nonadherent patients were in the normal metabolizer group (n=4) and are located along the upper part on the y axis with a heart rate of 70 to 80 beats/min.

Figure 5. Correlation between serum concentration of metoprolol and heart rate from another ongoing study.

Patients (n=104) using metoprolol prolonged release are classified into different cytochrome P450 2D6 phenotypes. Their mean daytime ambulatory heart rate (beats/min) are given on the y axis, and s‐[metoprolol] corrected for daily dose of metoprolol (nmol/L per mg) on the x axis. Nonadherent patients on the basis of their s‐[metoprolol] (n=4) were all normal metabolizers.

DISCUSSION

Seven of 19 patients with treatment‐resistant hypertension included in the Oslo RDN study and defined as drug adherent by DOT followed by daytime ABPM were further classified as either nonadherent or partially nonadherent on the basis of their serum concentration levels of the antihypertensive agents once or more during the 7‐year time span. As far as we know, this is the first time 2 objective methods for assessing adherence of antihypertensive medication are compared in patients with treatment‐resistant hypertension. Our findings illustrate that nonadherence may be underestimated and difficult to reveal and that some methods used to detect nonadherence might be more sensitive than others. Five patients would not have fulfilled the criteria of true treatment‐resistant hypertension and therefore would not have been accepted for RDN if measurement of serum concentrations had been mandatory at inclusion.

Any deviation from prescribed antihypertensive treatment or absence of at least 1 prescribed BP‐lowering medication or metabolite in biochemical analysis of body fluids has previously been used to define nonadherence to antihypertensive treatment. 7 , 23 Because of the retrospective design of our study with limited information of steady‐state status, we chose a very strict cutoff for nondetection as described in Data S1. Compared with DOT, serum concentration measurements require laboratory facilities, instruments, and technicians, but provide less risk of side effects such as discomfort related to cuff inflation during ABPM or hypotension. Serum concentrations also offer a possibility to categorize the nonadherence as partial or complete and detect the exact agent(s) that are being omitted. DOT provides a “yes” or “no” answer to the question of adherence, while serum concentrations may contribute to a more complete picture by taking more of the above‐mentioned parameters into account, and thereby offer a more personalized drug treatment and ideally better blood pressure control. However, both methods provide a narrow window of detection and give limited information about persistence, and they may be susceptible to white‐coat adherence. Used in clinical practice, patients’ consent to drug measurements in body fluids is mandatory to maintain a high ethical standard. 24 Since this may increase the risk of white‐coat adherence, one might come to an agreement with the patient to do random tests at some but not all visits. Identification of nonadherence is difficult because of the heterogeneity of the concept; the patients have to initiate the treatment, follow the prescription, and do so over time. 25 While adherence assesses how well a patient is taking a prescribed drug, persistence relates to how long the patient is adherent before discontinuation. 26 The phenomenon that adherence can vary over time and that repeated evaluation and close follow‐up may be necessary is clearly demonstrated in our study.

Polypharmacy, increased heart rate and BP (especially diastolic BP), previous stroke, and previous invasive treatment procedures (RDN or baroreceptor stimulation) are associated with increased probability of nonadherence according to the literature. 7 , 27 , 28 The nonadherent patients in the present study were younger and tended to have higher systolic BP, but prediction of nonadherence based on baseline characteristics remains challenging.

The difference in self‐reported adherence was low between the adherent and nonadherent patients, and these subjective methods have been proven unreliable on several previous occasions. 3 , 29 , 30 The lack of a defined time period opens for individual interpretation, and influence on the results cannot be ruled out. It is interesting to recognize the high scores reported by all patients, and one might speculate about different reasons for the discrepancy between the patients’ self‐reports and the drug concentrations measured.

Patients may have been tempted to overestimate their own adherence to please their doctors and even to be included in a medical research study. Why they did not start taking their drugs again after the procedure may include other reasons, and personal beliefs about medicines may be one explanation. It is understandable that the wish to get rid of all antihypertensive drugs with their side effects and costs may have led patients to nonadherence following the RDN procedure. This may also explain the high proportion of nonadherent patients generally observed in this particular population. 8 , 31 One of the highest reported rates of nonadherence (80%) comes from a study of RDN treatment 8 and pinpoints the necessity of adherence control of patients treated by RDN. While the Oslo RDN study 10 was one of the first RDN studies in which the investigators attempted to exclude nonadherent subjects before randomization, this is now routine in randomized RDN studies, though the methods to do so remain unstandardized. We observed an improvement in adherence among our patients during the 7 years. This may be related to the Hawthorne effect; drug adjustments; and education by, and increased trust in, our investigators.

Reasons for nonadherence may be diverse. Factors like organization of health care, costs, doctor–patient relationship, educational level, comorbidity, and side effects may all play a role, as well as the patients’ attitude toward treatment. 26 The BMQ offers a possibility to explore this attitude. The patients in our study were referred to a tertiary clinic for their difficult‐to‐treat hypertension; nevertheless, the BMQ revealed that the nonadherent patients believed that the necessity to take antihypertensive medication not clearly outweighed their concerns of taking them. This may be an important challenge to overcome to motivate the patients to improve their adherence. We did not do any specific intervention to change the patients’ beliefs, and their reported concerns and lack of necessity persisted throughout the study.

Since serum concentration of drugs is related not only to the actual intake but also to pharmacokinetic differences between subjects, a mapping of CYP polymorphisms is an important contribution to a broader comprehension of the field. Beta blockers are metabolized by CYP2D6, while CYP2C9 is involved in the metabolism of angiotensin II receptor blockers. Calcium channel blockers are mainly metabolized through CYP3A4. Diuretics and angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors are not usually affected by CYP metabolism 9 , 32 , 33 ; for details, see Data S1. Interestingly, we detected a higher proportion of CYP polymorphisms (especially CYP2D6 PMs) in our population than described in the general Norwegian population. 34 , 35 , 36 Six of 7 nonadherent patients had CYP polymorphisms affecting their metabolism of different antihypertensive drugs, mainly by reducing metabolism of beta blockers. 37 , 38 , 39 This may lead to higher‐than‐normal serum concentrations of drugs, which may lead to more serious side effects, which again might tempt patients not to take the drug or to take a lower dose than prescribed. Detailed records of side effects related to the time span a patient was administered a specific drug were not collected in our study. The patients’ medical regimen underwent several changes during the 7 years of follow‐up. These changes were made both as part of the study guided by integrated hemodynamic management using impedance cardiography or by study‐independent doctors. 11 One might speculate whether reduced beta blocker use during the study period was at least partly related to side‐effects. Also, if our patients experienced an increased rate of side effects attributable to their genetic polymorphisms, it may explain why obtaining BP control was difficult and why these patients were seeking other treatment options (eg, RDN). In patient A, who was nonadherent at baseline and at the 3‐year visit and reluctant to take any antihypertensive medications at the 7‐year visit, CYP analyses revealed a CYP2D6 PM phenotype as well as reduced CYP2C9 activity. This might to some degree explain the high level of side effects experienced by this patient and demonstrates the important role of CYP analyses in resistant hypertension. 9 , 32 Because all the nonadherent patients with CYP2D6 polymorphisms were either PMs or IMs, and the 1 nonadherent patient with increased CYP3A5 activity was nonadherent to lisinopril (ie, not metabolized by this enzyme, 100% renal clearance 33 ), low serum concentrations cannot be explained by CYP polymorphisms in the present material. On the other hand, nonadherence masked by reduced metabolism cannot be ruled out.

To provide supplementary information regarding CYP polymorphisms, serum concentrations of metoprolol, and clinical effects, we analyzed and included specific cross‐sectional data on metoprolol from 104 patients with hypertension treated with ≥2 antihypertensive drugs who participate in an ongoing study. 12 This study and these data are unrelated to the protocol on RDN, and patients were thus not selected on the basis of their motivation to qualify for this invasive procedure. However, these patients were recruited on the basis of being on ≥2 antihypertensive drugs and BP being uncontrolled—attempting to diagnose nonadherence. Otherwise, these 104 patients come from the same population as those who participated in the protocol on RDN followed through 7 years. PMs (n=4) and IMs with phenotype more like PMs (n=5) had high serum concentrations of metoprolol as expected, and they ranged low in mean daytime ambulatory heart rate. A few nonadherent patients were located high on the y axis. These data suggest that a high number of patients is needed to identify both PMs leading to nonadherence in patients with hypertension with uncontrolled BP. We have discussed previously 12 that nonadherent patients are difficult to recruit for studies. As shown in Figure 5, there is a negative relationship with heart rate. The question is whether patients could be nonadherent because they are PMs and subsequently high in serum concentrations of drugs, in this case metoprolol. Tentatively, high serum concentration of metoprolol may cause bradycardia, a potential unpleasant side effect that could lead to subsequent self‐discontinuation of drugs. We see a trend in our data shown in Figure 5, though we believe that the number of patients must be considerably higher than 104 to find whether PMs become nonadherent patients.

Our study had certain limitations, as 19 patients may be considered a small number. These patients were selected from 65 patients already worked up and referred from other hospitals and specialists who considered them true treatment resistant and ready for the device therapy. However, we did not at that time accept their resistance status and repeated the entire workup including DOT. All patients except the one who died, were followed for 7 years without missing any appointments. With 4 repetitive analyses during which serum concentrations of antihypertensive drugs were measured, we have restricted information regarding adherence between visits (ie, persistence). Specific instructions not to take their morning medications before study visits ensured that serum concentrations were measured at trough level at every visit. All serum analyses were performed in a retrospective way; hence, additional information to evaluate if antihypertensive drugs were measured in steady state was not obtained.

The relatively homogenous sample, all but 1 being White, is more a chance finding, though probably reflecting the Norwegian population. One might speculate whether this implies a cultural aspect, though we do not have data to support such an assumption.

In conclusion, repeated serum concentrations of antihypertensive drugs revealed nonadherence in one‐third of patients already tested and evaluated as adherent by directly observed therapy before inclusion in a controlled RDN study. Serum drug concentrations, current drug list, CYP polymorphisms, adverse effects, and patients’ necessity beliefs and concerns need to be considered together to evaluate and ideally improve drug adherence.

CONCLUSIONS

We believe that the direct method of serum drug measurements using ultra‐high‐performance liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry may improve detection of nonadherence to antihypertensive medication, and that this method of detection should be included in more extensive research and possibly routine clinical evaluations of adherence status in patients with hypertension. Recently, we found that measurements of serum drug concentrations were useful in detecting nonadherence to antihypertensive medication in patients using ≥2 antihypertensive agents. 12 Regarding patients using ≥3 antihypertensive agents, frequently in the category treatment resistance or apparent treatment‐resistant hypertension, and often recruited for RDN, serum and urine drug measurement as well as other objective methods including DOT have proved useful. However, when applying repeated measurements of serum drugs to patients previously considered adherent on the basis of DOT, one‐third of these patients nonetheless appeared nonadherent. Thus, whereas DOT is more challenging in clinical practice and research than drug measurements, serum drugs also appear more reliable. At this stage, such comparison is limited to patients recruited for RDN, a device therapy attractive for selected patients, and more research is needed to investigate whether DOT is inferior to serum drug measurement to detect nonadherence in the general population of patients using ≥3 antihypertensive agents.

Optimal or therapeutic ranges of antihypertensive drugs in serum are not yet established, 33 but in the future this may be used to individualize drug treatment. In the meantime, using smaller doses of several complementary drugs to achieve maximal BP lowering with fewer side effects may be a convenient strategy.

Sources of Funding

The original study was funded by "Oslo University Hospital", "Public health system in South‐Eastern Norwegian Regional Health Authority" and "The Einar Sissener Foundation, Department of Nephrology, Oslo University Hospital".

Disclosures

Dr Kjeldsen reports ad hoc lecture honoraria from Getz, Merck Healthcare KGaA, Sanofi, and Vector‐Intas. Dr Fadl Elmula reports lecture honoraria from Novo Nordisk. The remaining authors have no disclosures to report.

Supporting information

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Pavel Hoffman and Eigil Fossum, Department of Cardiology, Oslo University Hospital, who performed the RDN procedures at the outset of the present study. The authors also thank Prof. Emeritus Knut Liestøl, Departments of Informatics, University of Oslo, for statistical advice; Trine Helstrøm and Ingebjørg Gustavsen for their work in developing the pharmacological methods; and Anja C. Svarstad and Silja Skogstad Tuv, Department of Pharmacology, Oslo University Hospital for additional CYP analysis.

Supplemental Material is available at https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/suppl/10.1161/JAHA.121.025879

For Sources of Funding and Disclosures, see page 11.

REFERENCES

- 1. Eskas PA, Heimark S, Eek Mariampillai J, Larstorp AC, Fadl Elmula FE, Hoieggen A. Adherence to medication and drug monitoring in apparent treatment‐resistant hypertension. Blood Press. 2016;25:199–205. doi: 10.3109/08037051.2015.1121706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Berra E, Azizi M, Capron A, Høieggen A, Rabbia F, Kjeldsen SE, Staessen JA, Wallemacq P, Persu A. Evaluation of adherence should become an integral part of assessment of patients with apparently treatment‐resistant hypertension. Hypertension. 2016;68:297–306. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.116.07464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Durand CH, Hayes WP, Morrissey JE, Newell JJ, Casey JM, Murphy JA, Molloy GJ. Medication adherence among patients with apparent treatment‐resistant hypertension: systematic review and meta‐analysis. J Hypertens. 2017;35:2346–2357. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000001502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hjørnholm UA, Larstorp ACK, Fadl Elmula FEM, Høieggen A, Andersen MH, Kjeldsen SE. Directly observed therapy in hypertension (DOT‐HTN). In: Burnier M, ed. Drug Adherence in Hypertension and Cardiovascular Protection. Springer Nature; 2018:57–85. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fadl Elmula FEM, Hoffmann P, Fossum E, Brekke M, Gjonnaess E, Hjornholm U, Kjær VN, Rostrup M, Kjeldsen SE, Os I, et al. Renal sympathetic denervation in patients with treatment‐resistant hypertension after witnessed intake of medication before qualifying ambulatory blood pressure. Hypertension. 2013;62:526–532. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.113.01452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Brinker S, Pandey A, Ayers C, Price A, Raheja P, Arbique D, Das SR, Halm EA, Kaplan NM, Vongpatanasin W. Therapeutic drug monitoring facilitates blood pressure control in resistant hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:834–835. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.10.067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gupta P, Patel P, Strauch B, Lai FY, Akbarov A, Gulsin GS, Beech A, Marešová V, Topham PS, Stanley A, et al. Biochemical screening for nonadherence is associated with blood pressure reduction and improvement in adherence. Hypertension. 2017;70:1042–1048. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.117.09631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. de Jager RL, de Beus E, Beeftink MM, Sanders MF, Vonken EJ, Voskuil M, van Maarseveen EM, Bots ML, Blankestijn PJ, SYMPATHY Investigators . Impact of medication adherence on the effect of renal denervation: the SYMPATHY trial. Hypertension. 2017;69:678–684. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.116.08818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Eadon MT, Chapman AB. A physiologic approach to the pharmacogenomics of hypertension. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2016;23:91–105. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2016.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fadl Elmula FEM, Hoffmann P, Larstorp ACK, Fossum E, Brekke M, Kjeldsen SE, Gjønnæss E, Hjørnholm U, Kjaer VN, Rostrup M, et al. Adjusted drug treatment is superior to renal sympathetic denervation in patients with true treatment‐resistant hypertension. Hypertension. 2014;63:991–999. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.03246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bergland OU, Søraas CL, Larstorp ACK, Halvorsen LV, Hjørnholm U, Hoffman P, Høieggen A, Fadl Elmula FEM. The randomised Oslo study of renal denervation vs. antihypertensive drug adjustments: efficacy and safety through 7 years of follow‐up. Blood Press. 2021;30:41–50. doi: 10.1080/08037051.2020.1828818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bergland OU, Halvorsen LV, Søraas CL, Hjørnholm U, Kjær VN, Rognstad S, Brobak KM, Aune A, Olsen E, Fauchald YM, et al. Detection of nonadherence to antihypertensive treatment by measurements of serum drug concentrations. Hypertension. 2021;78:617–628. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.121.17514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mancia G, Fagard R, Narkiewicz K, Redon J, Zanchetti A, Böhm M, Christiaens T, Cifkova R, De Backer G, Dominiczak A, et al. 2013 ESH/ESC guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Blood Press. 2014;23:3–16. doi: 10.3109/08037051.2014.868629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Caudle KE, Sangkuhl K, Whirl‐Carrillo M, Swen JJ, Haidar CE, Klein TE, Gammal RS, Relling MV, Scott SA, Hertz DL, et al. Standardizing CYP2D6 genotype to phenotype translation: consensus recommendations from the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium and Dutch Pharmacogenetics Working Group. Clin Transl Sci. 2020;13:116–124. doi: 10.1111/cts.12692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Finitsis DJ, Pellowski JA, Huedo‐Medina TB, Fox MC, Kalichman SC. Visual analogue scale (VAS) measurement of antiretroviral adherence in people living with HIV (PLWH): a meta‐analysis. J Behav Med. 2016;39:1043–1055. doi: 10.1007/s10865-016-9770-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sevilla‐Cazes J, Finkleman BS, Chen J, Brensinger CM, Epstein AE, Streiff MB, Kimmel SE. Association between patient‐reported medication adherence and anticoagulation control. Am J Med. 2017;130:1092–1098.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.03.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Stavem K, Augestad LA, Kristiansen IS, Rand K. General population norms for the EQ‐5D‐3 L in Norway: comparison of postal and web surveys. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2018;16:204–214. doi: 10.1186/s12955-018-1029-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Horne R, Weinman J, Hankins M. The beliefs about medicines questionnaire: the development and evaluation of a new method for assessing the cognitive representation of medication. Psychol Health. 1999;14:1–24. doi: 10.1080/08870449908407311 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jónsdóttir H, Friis S, Horne R, Pettersen KI, Reikvam Å, Andreassen OA. Beliefs about medications: measurement and relationship to adherence in patients with severe mental disorders. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2009;119:78–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2008.01279.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Viktil KK, Frøyland H, Rogvin M, Moger TA. Beliefs about medicines among Norwegian outpatients with chronic cardiovascular disease. Eur J Hosp Pharm. 2014;21:118–120. doi: 10.1136/ejhpharm-2013-000346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Drangsholt SH, Cappelen UW, von der Lippe N, Høieggen A, Os I, Brekke FB. Beliefs about medicines in dialysis patients and after renal transplantation. Hemodial Int. 2019;23:117–125. doi: 10.1111/hdi.12717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Horne R, Weinman J. Patients' beliefs about prescribed medicines and their role in adherence to treatment in chronic physical illness. J Psychosom Res. 1999;47:555–567. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(99)00057-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tomaszewski M, White C, Patel P, Masca N, Damani R, Hepworth J, Samani NJ, Gupta P, Madira W, Stanley A, et al. High rates of non‐adherence to antihypertensive treatment revealed by high‐performance liquid chromatography‐tandem mass spectrometry (HP LC‐MS/MS) urine analysis. Heart. 2014;100:855–861. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2013-305063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mariampillai JE, Eskås PA, Heimark S, Larstorp ACK, Fadl Elmula FEM, Høieggen A, Nortvedt P. Apparent treatment‐resistant hypertension‐patient‐physician relationship and ethical issues. Blood Press. 2017;26:133–138. doi: 10.1080/08037051.2016.1277129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Vrijens B, Antoniou S, Burnier M, de la Sierra A, Volpe M. Current situation of medication adherence in hypertension. Front Pharmacol. 2017;8:1–7. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2017.00100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Burnier M, Egan BM. Adherence in hypertension. Circ Res. 2019;124:1124–1140. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.313220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Avataneo V, De Nicolò A, Rabbia F, Perlo E, Burrello J, Berra E, Pappaccogli M, Cusato J, D'Avolio A, Di Perri G, et al. Therapeutic drug monitoring‐guided definition of adherence profiles in resistant hypertension and identification of predictors of poor adherence. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2018;84:2535–2543. doi: 10.1111/bcp.13706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Heimark S, Eskås PA, Mariampillai JE, Larstorp ACK, Høieggen A, Fadl Elmula FEM. Tertiary work‐up of apparent treatment‐resistant hypertension. Blood Press. 2016;25:312–318. doi: 10.3109/08037051.2016.1172865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Pandey A, Raza F, Velasco A, Brinker S, Ayers C, Das SR, Morisky DE, Halm EA, Vongpatanasin W. Comparison of Morisky Medication Adherence Scale with therapeutic drug monitoring in apparent treatment‐resistant hypertension. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2015;9:420–426.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jash.2015.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mäenpää H, Manninen V, Heinonen OP. Comparison of the digoxin marker with capsule counting and compliance questionnaire methods for measuring compliance to medication in a clinical trial. Eur Heart J. 1987;8:39–43. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/8.suppl_I.39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Schmieder RE, Ott C, Schmid A, Friedrich S, Kistner I, Ditting T, Veelken R, Uder M, Toennes SW. Adherence to antihypertensive medication in treatment‐resistant hypertension undergoing renal denervation. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5:e002343. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.115.002343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Joy MS, Dornbrook‐Lavender K, Blaisdell J, Hilliard T, Boyette T, Hu Y, Hogan SL, Candiani C, Falk RJ, Goldstein JA. CYP2C9 genotype and pharmacodynamic responses to losartan in patients with primary and secondary kidney diseases. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;65:947–953. doi: 10.1007/s00228-009-0707-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rognstad S, Søraas CL, Bergland OU, Høieggen A, Strømmen M, Helland A, Opdahl MS. Establishing serum reference ranges for antihypertensive drugs. Ther Drug Monit. 2021;43:116–125. doi: 10.1097/FTD.0000000000000806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sachse C, Brockmöller J, Bauer S, Roots I. Cytochrome P450 2D6 variants in a Caucasian population: allele frequencies and phenotypic consequences. Am J Hum Genet. 1997;60:284–295. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Anstensrud AK, Molden E, Haug HJ, Qazi R, Muriq H, Fosshaug LE, Spigset O, Øie E. Impact of genotype‐predicted CYP2D6 metabolism on clinical effects and tolerability of metoprolol in patients after myocardial infarction—a prospective observational study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2020;76:673–683. doi: 10.1007/s00228-020-02832-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Whirl‐Carrillo M, McDonagh EM, Hebert JM, Gong L, Sangkuhl K, Thorn CF, Altman RB, Klein TE. Pharmacogenomics knowledge for personalized medicine. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2012;92:414–417. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2012.96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Blake CM, Kharasch ED, Schwab M, Nagele P. A meta‐analysis of CYP2D6 metabolizer phenotype and metoprolol pharmacokinetics. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2013;94:394–399. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2013.96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Thomas CD, Mosley SA, Kim S, Lingineni K, El Rouby N, Langaee TY, Gong Y, Wang D, Schmidt SO, Binkley PF, et al. Examination of metoprolol pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics across CYP2D6 genotype‐derived activity scores. CPT Pharmacometrics Syst Pharmacol. 2020;9:678–685. doi: 10.1002/psp4.12563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Jukić MM, Smith RL, Molden E, Ingelman‐Sundberg M. Evaluation of the CYP2D6 haplotype activity scores based on metabolic ratios of 4,700 patients treated with three different CYP2D6 substrates. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2021;110:750–758. doi: 10.1002/cpt.2246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Burnier M, Vrijens B. Taxonomy of medication adherence: recent developments. In: Burnier M, ed. Drug Adherence in Hypertension and Cardiovascular Protection. Springer Nature; 2018:5–6. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.