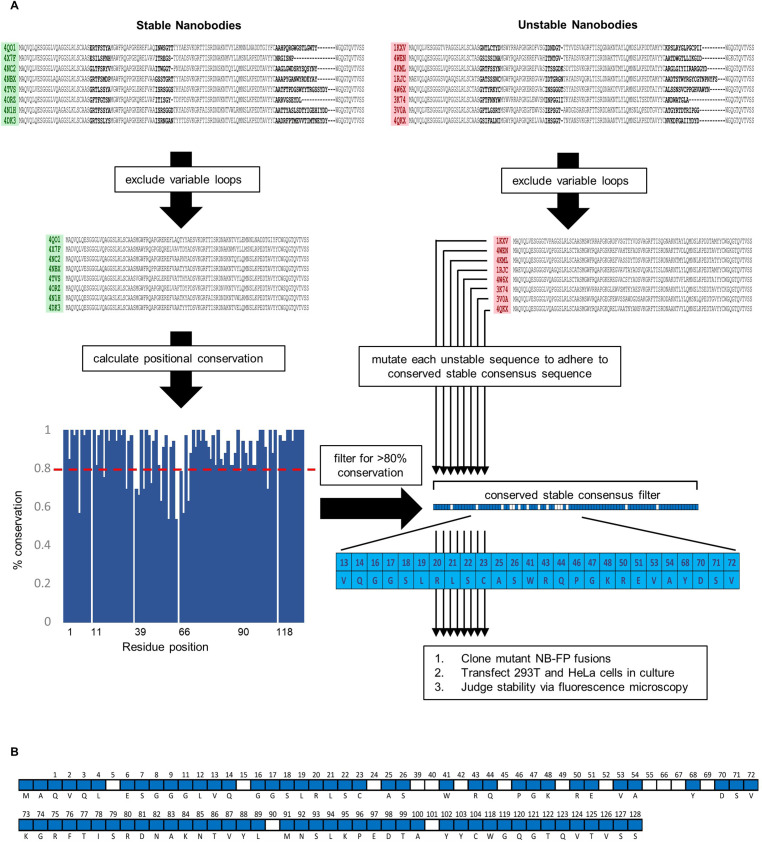

Figure 3. Schematic overview of conservation-based stabilizing mutagenesis strategy.

(A) Nanobody-TagBFP fusions were classified as ‘stable’ or ‘unstable’ based on intracellular expression via transient transfection in 293T cells. Amino acid sequences were binned according to stability group, and variable domain sequences (CDRs) were excluded from downstream consideration. Positional sequence conservation was calculated across stable nanobody sequences, and positional amino acids of high conservation (>80%) were compiled to form a partial consensus filter. Each individual unstable nanobody framework was then compared to this filter, and any positional amino acid disagreement was resolved to adhere to the filter. Mutated nanobodies were then cloned, transfected into 293T and HeLa cells, and judged for stability via fluorescence microscopy. (B) All positional amino acids captured in the partial consensus framework (blue cells). White cells denote framework positions excluded from the partial consensus framework.