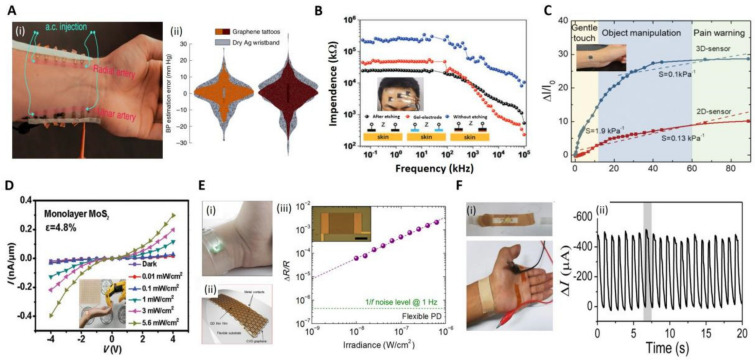

Figure 2.

Several e−skins based on 2D materials. (A): (i) Photo of the graphene bioimpedance tattoos attached to human skin. (ii) Comparison of statistical violin plots of graphene Z−BP versus commercial dry silver wristbands (diastolic (left) and systolic (right)) [97]. Copyright 2022, Springer Nature. (B): Impedance difference between LSG/PU e−skin with and without etched PU and commercial gel electrodes during measurement (the illustration shows the optical image when worn on the user’s head) [98]. Copyright 2022, Wiley-VCH. (C): Relative current change versus applied pressure for the pressure sensors based on 3D microelectrodes and 2D flat electrodes, where S represents the sensitivity of the pressure sensor; inset shows a photo of the sensor attached to the skin [86]. Copyright 2019, Wiley−VCH. (D): Current versus source−drain voltage on a single layer of MoS2; illustration of this elastomeric substrate attached to a human wrist for lighting detection and human–machine interaction [90]. Copyright 2022, Wiley-VCH. (E): (i) Physical diagram of reflection mode photodetector. (ii) Schematic illustration of the assembly of graphene and QDs on a flexible substrate. (iii) Photo-induced resistance change (ΔR/R) with respect to irradiance at 633 nm. [87]. Copyright 2019, American Association for the Advancement of Science. (F): (i) Photograph of the measurement for wrist pulses. (ii) 20 s real-time record of wrist pulses [91]. Copyright 2017, American Chemical Society.