Abstract

Background:

Most coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)-related cerebrovascular disorders are ischemic while hemorrhagic disorders are rarely reported. Among these, subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) is very rarely reported and nonaneurysmal SAH has been reported in only about a dozen cases. Here, we report a case of nonaneurysmal SAH as the only clinical manifestation of COVID-19 infection. In addition, we reviewed and analyzed the literature data on cases of nonaneurysmal SAH caused by COVID-19 infection.

Case Description:

A 50-year-old woman presented to an emergency department with a sudden headache, right hemiparesis, and consciousness disturbance. At that time, no fever or respiratory failure was observed. Laboratory data were within normal values but the rapid antigen test for COVID-19 on admission was positive, resulting in a diagnosis of COVID-19 infection. Computed tomograms (CTs) showed bilateral convexal SAH with a hematoma but three-dimensional CT angiograms showed no obvious sources, such as a cerebral aneurysm. Therefore, the patient was diagnosed with nonaneurysmal SAH associated with COVID-19 infection. With conservative treatment, consciousness level and hemiparesis both improved gradually until transfer for continued rehabilitation. Approximately 12 weeks after onset, the patient was discharged with only mild cognitive impairment. During the entire course of the disease, the headache, hemiparesis, and mild cognitive impairment due to nonaneurysmal SAH with small hematoma were the only abnormalities experienced.

Conclusion:

Since COVID-19 infection can cause nonaneurysmal hemorrhaging, it should be considered (even in the absence of characteristic infectious or respiratory symptoms of COVID-19) when atypical hemorrhage distribution is seen as in our case.

Keywords: Coronavirus disease 2019, Nonaneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage, Stroke

INTRODUCTION

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is an infectious disease caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). COVID-19 infection can affect the respiratory tract and other organs, including the brain, and is considered a risk factor for multiorgan ischemic and hemorrhagic diseases.[18] For example, it has been reported that approximately 0.7–1.4% of COVID-19 infections result in a stroke.[18] It is also known to cause coagulation abnormalities and ischemic strokes are more common than hemorrhagic strokes. In addition, COVID-19- related strokes tend to develop in younger patients with more severe manifestations than strokes in uninfected patients.[19]

A higher incidence of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) has been reported in COVID-19 patients, but whether this increase is incidental or related is controversial.[3,4] In addition, there are few reports on the association between COVID-19 and nonaneurysmal SAH, especially regarding clinical features still poorly understood.

Here, we describe a case of nonaneurysmal SAH with small hematoma, resulting in headache, hemiparesis, and mild cognitive impairment as the only abnormalities related to COVID-19 infection. We also review previously reported cases of nonaneurysmal SAH associated with COVID-19 infection and discuss their characteristics.

CASE DESCRIPTION

A 50-year-old woman came to our emergency department complaining of a sudden headache, right hemiparesis, and loss of consciousness. She had no significant or relevant medical history other than a previous, small, and unruptured cerebral aneurysm for which she had undergone regular imaging.

On admission, physical examination revealed a body temperature of 98.2°F, respiratory rate of 20 breaths/min, peripheral oxygen saturation of 98% on room air, and blood pressure of 147/86 mmHg. The right hemiparesis with the upper extremity predominance and mild consciousness disturbance was observed. General laboratory findings, including thyroid function and factors associated with collagen diseases, were within normal ranges, and there were no inflammatory findings or coagulation abnormalities (PT: 11.1 s, APTT: 28.7 s, and D-dimer: 0.7 μg/dl). Our institution performs antigen testing in all patients who require hospitalization to prevent nosocomial infection; this patient tested positive by the rapid antigen test and was diagnosed with COVID-19. The chest X-ray was normal, and the chest computed tomogram (CT) showed no pneumonia. CT of the brain showed SAH over a wide area of the bilateral convexal regions and a hematoma in the left frontal sulci [Figure 1]. A three-dimensional CT angiogram showed no vascular lesions that could be an obvious hemorrhage source. An aneurysm of the left internal carotid artery was identified, which had been previously indicated, but it appeared to be unruptured based on the SAH distribution [Figure 2a].

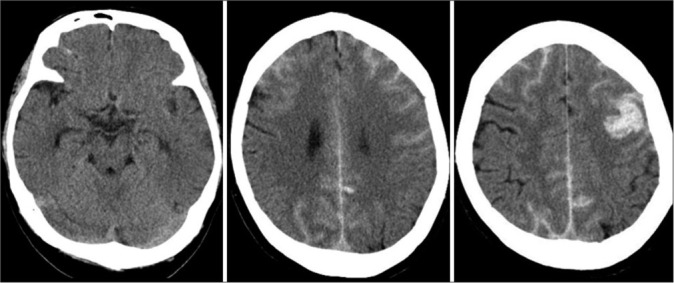

Figure 1:

Computed tomograms on admission showing bilateral subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) with a hematoma in the left frontal sulci (middle and right). No SAH is seen in the basal cistern (left).

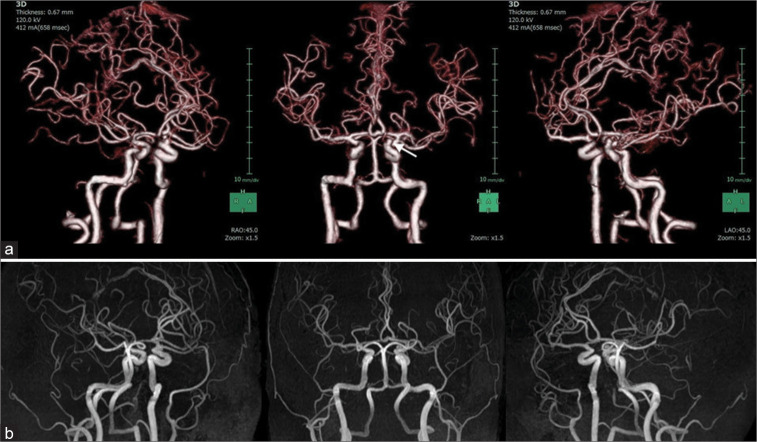

Figure 2:

(a) Three-dimensional computed tomographic angiograms showing no clear source of hemorrhage. A small aneurysm arising from the left internal carotid artery (arrow) appears to be unruptured. (b) Magnetic resonance angiograms at discharge showing no clear source of hemorrhage.

Although no respiratory symptoms were present, remdesivir was administered for the viral infection, as SAH is a likely indicator of severe COVID-19. In addition, conservative treatment, including hemostatic agent administration, osmotic therapy, blood pressure control, and continuous rehabilitation, gradually improved neurological deficits such as consciousness disturbance and hemiparesis. Magnetic resonance (MR) angiograms and contrast-enhanced MR images 14 days after admission showed no vascular or neoplastic lesions suggestive of a hemorrhage source. Approximately 12 weeks after onset, the patient was discharged with only mild cognitive impairment. During hospitalization, the patient had no respiratory symptoms or recurrent hemorrhagic/ ischemic strokes. No hemorrhage sources were seen on MR images at the time of discharge [Figure 2b].

DISCUSSION

SAH is primarily caused by trauma or ruptured cerebral aneurysms but other causes include rupture of abnormal vessels (such as arteriovenous malformations and arteriovenous fistulas), vasculitis, tumors, arterial dissection, moyamoya disease, coagulation abnormalities, cocaine abuse, sickle cell disease, infection, perimesencephalic nonaneurysmal SAH, cerebral venous thrombosis, reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome, posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome, cerebral amyloid angiopathy, and others.[13,14,20] Regardless of cause, SAH is a severe disease with a poor prognosis, requiring case- and cause-specific treatment. Therefore, it is essential to promptly identify the cause of hemorrhaging. In our case, COVID-19 infection appeared to have caused nonaneurysmal SAH. Although the presence of a nonvisualized small aneurysm or dissection in the left frontal hematoma could not be ruled out, no clear source of bleeding was identified on MR imaging (including MR angiography) at admission, 14 days after admission, or at discharge.

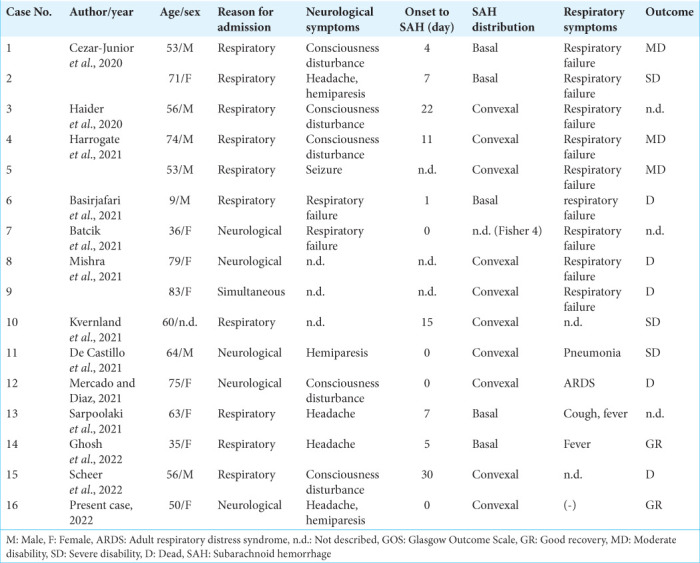

A literature review revealed 16 cases of nonaneurysmal SAH associated with COVID-19 infection, including ours [Table 1].[1-4,6,7,9,12,16,17,23,24] The average age of onset for nonaneurysmal SAH associated with COVID-19 infection was 57 years, similar to SAH due to cerebral aneurysm rupture. There was no gender difference in COVID-19-associated nonaneurysmal SAH, while SAH due to cerebral aneurysm rupture seems to be more common in women.

Table 1:

Summary of the cases with nonaneurysmal SAH associated with COVID-19 infection.

Among these cases, preceding neurological symptoms were extant in 5 cases (31.3%) and respiratory symptoms were seen in 11 cases (68.8%), indicating the challenge of precise COVID-19 infection diagnosis based on chief complaints in about 1/3 of the cases. Of the total cases, eight exhibited severe respiratory failure requiring ventilation but, even with preceding neurological symptoms, severe respiratory failure was later observed in 3 out of 5 patients (60.0%). Therefore, COVID-19 infection respiratory status requires continuous monitoring even if no initial abnormalities are observed.

Some cases presented stroke-specific symptoms, such as consciousness disturbance and hemiplegia, while others had only nonspecific symptoms such as headache. Headache is a common symptom of infectious diseases but the possibility of nonaneurysmal SAH should always be considered. As reported intervals from infection to nonaneurysmal SAH onset ranged from 0 to 30 days (average of 7.8 ± 9.4 days), COVID-19 patients could develop SAH at approximately 2 weeks after infection.

In addition, SAH distribution patterns in COVID-19 patients often differed from those caused by ruptured cerebral aneurysms. Ruptured cerebral aneurysm patterns for SAH vary depending on location but they generally spread in the basal cistern. In contrast, COVID-19 patients have a more peripheral hemorrhage distribution in the cortical areas. Several hemorrhagic mechanisms focused on vascular endothelial damage have been postulated for the etiology of SAH in COVID-19, including vascular barrier damage associated with hypercytokinemia, virus-induced endothelial damage, coagulopathy, and immune thrombocytopenia.[5,8,28] In addition, small peripheral arteries are more susceptible to vascular injury than the thick-walled main arteries of the brain, which may explain why SAH caused by COVID-19 infection is more common in cortical areas.

Some COVID-19 patients also had multiple cerebral infarctions.[4,7,17] In ruptured cerebral aneurysms, cerebral infarction due to vasospasm may be seen which tends to coincide with the perfusion area of the spasmed vessel. In contrast, as seen in embolisms, COVID-19 patients tended to have multiple occurrences that did not coincide with the perfusion area of a single vessel.

Of the 13 patients with known prognoses, 5 (38.5%) had a favorable outcome, while 3 (23.1%) were severe disability and 5 (38.5%) died. The high mortality rate compared to typical COVID-19 infection (8.3~10%)[11,22] was probably due to cumulative CNS damage caused by SAH and systemic damage caused by COVID-19 infection. Although such damage most likely indicates severe COVID-19, favorable outcomes may be obtained, even in the presence of SAH, as in our case. Therefore, appropriate treatment of both systemic infection and SAH-induced brain damage is necessary for a good prognosis while a prompt diagnosis of COVID-19 infection is essential.

Numerous reports of viral infections and nonaneurysmal SAH have been associated with COVID-19 caused by SARS-CoV-2,[1-4,6,7,9,12,16,17,23,24] while some have been associated with other viruses including human immunodeficiency virus, herpes simplex virus, Epstein–Barr virus, Jamestown Canyon virus, and varicella zoster virus.[10,15,21,25-27] Interestingly, there have been no reports of nonaneurysmal SAH caused by coronaviruses other than SARS-CoV-2, such as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 1 (SARS-CoV-1 or simply SARS-CoV) and Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. As such, the true affinity of SARS-CoV-2 with cerebral vessels remains unknown in spite of an increasing number of reported cases. Further epidemiological and clinical studies are needed to clarify the relationship between COVID-19 infection and nonaneurysmal SAH and to find appropriate treatment.

CONCLUSION

In this report, we described a case of COVID-19 infection where nonaneurysmal SAH was an isolated symptom. There are two important lessons to be learned from this case. First, COVID-19 infection can cause nonaneurysmal SAH, which often has atypical hematoma distribution. Second, COVID-19 infection should be suspected in patients with atypical SAH distribution, even without typical infectious signs (such as fever or respiratory symptoms).

Footnotes

How to cite this article: Kajita M, Yanaka K, Akimoto K, Aiyama H, Ishii K, Ishikawa E. Nonaneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage associated with COVID-19 infection: A case report. Surg Neurol Int 2022;13:524.

Contributor Information

Michihide Kajita, Email: aquas_jersey@me.com.

Kiyoyuki Yanaka, Email: kyanaka@ybb.ne.jp.

Ken Akimoto, Email: ke.aki54@gmail.com.

Hitoshi Aiyama, Email: jinaiyama@hotmail.com.

Kazuhiro Ishii, Email: kazishii@md.tsukuba.ac.jp.

Eiichi Ishikawa, Email: e-ishikawa@md.tsukuba.ac.jp.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient’s consent not required as patient’s identity is not disclosed or compromised.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Journal or its management. The information contained in this article should not be considered to be medical advice; patients should consult their own physicians for advice as to their specific medical needs.

REFERENCES

- 1.Basirjafari S, Rafiee M, Shahhosseini B, Mohammadi M, Neshin SA, Zarei M. Association of pediatric COVID-19 and subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Med Virol. 2021;93:658–60. doi: 10.1002/jmv.26434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Batcik OE, Kanat A, Cankay TU, Ozturk G, Kazancıoglu L, Kazdal H, et al. COVID-19 infection produces subarachnoid hemorrhage; Acting now to understand its cause: A short communication. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2021;202:106495. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2021.106495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cezar-Junior AB, Faquini IV, Silva JL, de Carvalho Junior EV, Lemos LE, Filho JB, et al. Subarachnoid hemorrhage and COVID-19: Association or coincidence? Medicine (Baltimore) 2020;99:e23862. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000023862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Castillo LL, Diestro JD, Ignacio KH, Separa KJ, Pasco PM, Franks MC. Concurrent acute ischemic stroke and non-aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage in COVID-19. Can J Neurol Sci. 2021;48:587–8. doi: 10.1017/cjn.2020.242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ghosh R, Roy D, Ray A, Mandal A, Das S, Pal SK, et al. Nonaneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage in COVID-19: A case report and review of literature. Med Res Arch. 2022;10:2673. doi: 10.18103/mra.v10i1.2673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haider A, Schmitt C, Greim CA. Multiorgan point-of-care ultrasound in a patient with coronavirus disease 2019 pneumonia complicated by subarachnoid hemorrhage and pulmonary embolism. A A Pract 2020 ; 14:e01357. doi: 10.1213/XAA.0000000000001357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harrogate S, Mortimer A, Burrows L, Fiddes B, Thomas I, Rice CM. Non-aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage in COVID-19. Neuroradiology. 2021;63:149–52. doi: 10.1007/s00234-020-02535-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iba T, Levi M, Levy JH. Sepsis-induced coagulopathy and disseminated intravascular coagulation. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2020;46:89–95. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-1694995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ildan F, Tuna M, Erman T, Göçer AI, Cetinalp E. Prognosis and prognostic factors in nonaneurysmal perimesencephalic hemorrhage: A follow-up study in 29 patients. Surg Neurol. 2002;57:160–5. doi: 10.1016/s0090-3019(02)00630-4. discussion 165-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khan F, Sharma N, Ud Din M, Shirke S, Abbas S. Convexal subarachnoid hemorrhage caused by infective endocarditis in a patient with advanced Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV): The culprits and bystanders. Am J Case Rep. 2021;22:e931376. doi: 10.12659/AJCR.931376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Konczalla J, Platz J, Schuss P, Vatter H, Seifert V, Güresir E. Non-aneurysmal non-traumatic subarachnoid hemorrhage: Patient characteristics, clinical outcome and prognostic factors based on a single-center experience in 125 patients. BMC Neurol. 2014;14:140. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-14-140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kvernland A, Kumar A, Yaghi S, Raz E, Frontera J, Lewis A, et al. Anticoagulation use and hemorrhagic stroke in SARSCoV-2 patients treated at a New York healthcare system. Neurocrit Care. 2021;34:748–59. doi: 10.1007/s12028-020-01077-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marushima A, Yanaka K, Matsuki T, Kojima H, Nose T. Subarachnoid hemorrhage not due to ruptured aneurysm in moyamoya disease. J Clin Neurosci. 2006;13:146–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2005.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matsumaru Y, Yanaka K, Muroi A, Sato H, Kamezaki T, Nose T. Significance of a small bulge on the basilar artery in patients with perimesencephalic nonaneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Report of two cases. J Neurosurg. 2003;98:426–9. doi: 10.3171/jns.2003.98.2.0426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matsumoto S, Matsumoto E. A 20-month-old girl with fever, seizures, hemiparesis, and brain lesions requiring a diagnostic brain biopsy. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 2018;26:80–2. doi: 10.1016/j.spen.2017.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mercado ES, Diaz JB. Spontaneous non-aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage as initial presentation of COVID-19: A case report. Med Rep Case Stud. 2021;6:224. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mishra S, Choueka M, Wang Q, Hu C, Visone S, Silver M, et al. Intracranial hemorrhage in COVID-19 patients. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2021;30:105603. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2021.105603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nannoni S, de Groot R, Bell S, Markus HS. Stroke in COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Stroke. 2021;16:137–49. doi: 10.1177/1747493020972922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ntaios G, Michel P, Georgiopoulos G, Guo Y, Li W, Xiong J, et al. Characteristics and outcomes in patients with COVID-19 and acute ischemic stroke: The global COVID-19 stroke registry. Stroke. 2020;51:e254–8. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.031208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Renou P, Tourdias T, Fleury O, Debruxelles S, Rouanet F, Sibon I. Atraumatic nonaneurysmal sulcal subarachnoid hemorrhages: A diagnostic workup based on a case series. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2012;34:147–52. doi: 10.1159/000339685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rios J, Félix C, Proença P, Malaia L, Nzwalo H. Ischemic stroke and subarachnoid hemorrhage following epstein-barr virus infection. J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2020;11:680–1. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1717827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rinkel GJ, Wijdicks EF, Hasan D, Kienstra GE, Franke CL, Hageman LM, et al. Outcome in patients with subarachnoid haemorrhage and negative angiography according to pattern of haemorrhage on computed tomography. Lancet. 1991;338:964–8. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)91836-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sarpoolaki MK, Iranmehr A, Bitaraf MA, Naderi S, Namvar M. Non-aneurysmal perimesencephalic subarachnoid hemorrhage in a COVID-19 patient: Case report and review on subarachnoid hemorrhage patterns in COVID-19. Iran J Neurosurg. 2021;7:213–8. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scheer M, Harder A, Wagner S, Ibe R, Prell J, Scheller C, et al. Case report of a fulminant non-aneurysmal convexity subarachnoid hemorrhage after COVID-19. Interdiscip Neurosurg. 2022;27:101437. doi: 10.1016/j.inat.2021.101437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Silvestrini M, Floris R, Tagliati M, Stanzione P, Sancesario G. Spontaneous subarachnoid hemorrhage in an HIV patient. Ital J Neurol Sci. 1990;11:493–5. doi: 10.1007/BF02336570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tonomura Y, Kataoka H, Yata N, Kawahara M, Okuchi K, Ueno S. A successfully treated case of herpes simplex encephalitis complicated by subarachnoid bleeding: A case report. J Med Case Rep. 2010;4:310. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-4-310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.VanderVeen N, Nguyen N, Hoang K, Parviz J, Khan T, Zhen A, et al. Encephalitis with coinfection by Jamestown canyon virus (JCV) and varicella zoster virus (VZV) IDCases. 2020;22:e00966. doi: 10.1016/j.idcr.2020.e00966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zulfiqar AA, Lorenzo-Villalba N, Hassler P, Andrès E. Immune thrombocytopenic purpura in a patient with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:e43. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2010472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]