Abstract

Background

Identifying polymorphism clades on phylogenetic trees could help detect punctual mutations that are associated with viral functions. With visualization tools coloring the tree, it is easy to visually find clades where most sequences have the same polymorphism state. However, with the fast accumulation of viral sequences, a computational tool to automate this process is urgently needed.

Results

Here, by implementing a branch-and-bound-like search method, we developed an R package named sitePath to identify polymorphism clades automatically. Based on the identified polymorphism clades, fixed and parallel mutations could be inferred. Furthermore, sitePath also integrated visualization tools to generate figures of the calculated results. In an example with the influenza A virus H3N2 dataset, the detected fixed mutations coincide with antigenic shift mutations. The highly specificity and sensitivity of sitePath in finding fixed mutations were achieved for a range of parameters and different phylogenetic tree inference software.

Conclusions

The result suggests that sitePath can identify polymorphism clades per site. The clustering of sequences on a phylogenetic tree can be used to infer fixed and parallel mutations. High-quality figures of the calculated results could also be generated by sitePath.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12859-022-05064-4.

Keywords: Phylogenetics, Sequence analysis, Visualization

Background

Identifying polymorphism clades on phylogenetic tree could help detect punctual mutations that are associated with viral function. In viral evolution, fixed mutation, which quickly dominates the viral population since its initial introduction, is accompanied by the formation of polymorphism clades and is usually associated with the shift of key functions [1, 2]. While parallel mutation, which refers to the mutation occurring independently in different polymorphism clades, has a high probability of being the result of natural selection under selective pressure [3].

With visualization tools coloring the tree branches according to a selected site, it is easy to visually find clades where most sequences have the same polymorphism state. However, with the increasing viral sequences in public database, a tool to automate this process is needed. A reasonable algorithm aimed at resolving a given phylogenetic tree into polymorphism clades should consider both the site polymorphism and the tree topology, which is not included in current methods [4, 5].

In this study, we developed an R package named sitePath to resolve tree trunks and identify polymorphism clades per site automatically. Using aligned sequences and an estimated tree as input, sitePath resolves tree trunks by clustering sequences with the same polymorphism state and implements a branch-and-bound-like search method to identify polymorphism clades per site through entropy minimization. The function of Inferring fixed mutation, parallel mutation and visualizing the calculated results are all integrated into the R package.

Implementation

Identification of phylogenetic tree trunks

To resolve tree trunks, sitePath assumes that most descendant sequences of each terminal node have the same polymorphism state. The Treemmer algorithm [6] collapses tree tips and guarantees that the collapsed tree tips are within a monophyletic group. Here, the terminating condition for the Treemmer algorithm is changed to tree tips having the same polymorphism state. However, it is difficult to retrieve a monophyletic group when a few sequences in the group have different polymorphism states than the dominant one (Fig. 1A). The modified Treemmer algorithm would identify a few smaller groups instead of a single monophyletic group. To address this issue, another method similar to CD-HIT [7] is implemented in an attempt to merge the smaller groups. The rule is that the average similarity of the group after merging is no lower than a threshold. The groups of sequences to be merged depend on which site being evaluated. It is therefore impossible to define a universal threshold for all sites. Instead, a universal rule for generating the threshold value is set as the median similarity of the sequences. Furthermore, a polymorphism state has to exist in enough sequences to be valid for defining clades and tree trunk terminals. Thus, the group with the number of sequences less than the predefined (the minimum number of sequences to define a valid polymorphism clade) will be treated as outlier and dropped. The tree trunks are found by linking the tree root and the ancestral node of all resulting groups. Only the longest tree trunks are retained if there are overlaps (Fig. 1A).

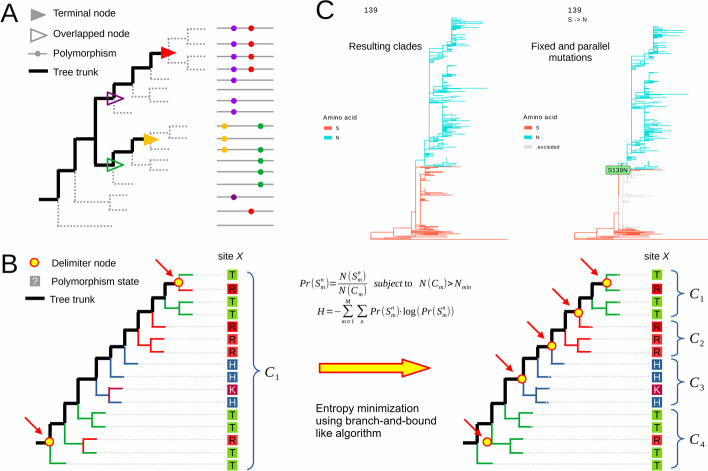

Fig. 1.

Schematics and demonstration of sitePath. A All sequences but one on the upper side are in a monophyletic group with the purple polymorphism, which is also true for the sequences with the green polymorphism; the ancestral nodes of purple and red overlap on tree trunks so only red is retained, which is also the case for the gold and green polymorphisms. B For site , the initial entropy is calculated by clading all sequences as ; the minimum entropy is achieved here when the clade set is found. The tree is colored according to the polymorphism state of site before clading and the dominant polymorphism state after clading. C An example of the resulting clades and mutation detection of the ZIKA virus dataset for site 139 of the polyprotein

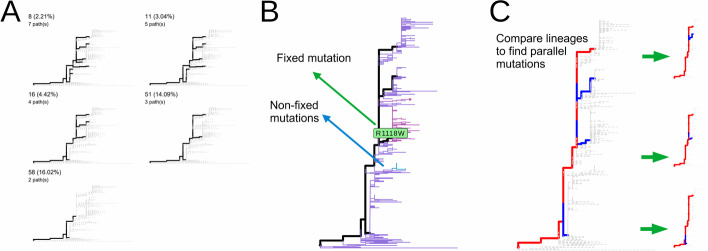

The phylogenetic pathways are derived from tree trunks. A phylogenetic pathway can be a combination of tree trunks to describe the ancestral and descendant relationships of clades. A clade closer to the tree root is defined to be ancestral to its neighbor clade. The default value depends on the total number of sequences in the input dataset. In sitePath, the default is defined as the number of pathways remains the same for a few consecutive values. For an input file containing all the available sequences of a virus or a proportional subsampled dataset of it, the default is recommended. While for a partial dataset of a virus, sitePath provides a method to help find the best (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

Default value and recognition of fixed and parallel mutations. A Visualization of phylogenetic pathways using five different . B Fixed and non-fixed mutations were identified along a phylogenetic pathway. C The parallel mutation was recognized by comparing mutations between pairs of pathways

Branch-and-bound search for polymorphism clades

A branch-and-bound like search method is implemented to minimize the entropy of the polymorphism state across clades. The search is independently performed per site per tree trunk and the site will be referred as site in this section. The goal is to search for tree trunk nodes delimiting the sequences into such clade set that the total entropy is minimized (Fig. 1B). Assume in clade there are sequences in total and sequences with polymorphism state for site . Then the probability of drawing polymorphism state in is . The search starts with initial entropy by treating all sequences on the tree trunk as a single clade delimited by the tree root and the terminal node. Then, the search branches to explore new clade sets through iterations to find the goal clade set with the minimum entropy .

A breadth-first searching strategy is used, meaning that all possible clade sets branched from the previous clade set are evaluated when proceeding with the search. All of a newly branched clade set is constrained to be greater than the predefined otherwise it will become inactive in later iterations. For each iteration, all the newly branched and other active clade sets are compared to find the temporary best solution with the lowest value. This is because is not monotonically decreasing in the search towards the goal clade set. The search is terminated when the temporary best solution stays the best after a few iterations. It is set as the total number of nodes of the tree trunk by default and can be folded by user to elongate the search.

Fixed and parallel mutation

The result can be further used to find fixed and parallel mutations in phylogenetic pathways (Fig. 2). Fixed mutation was found by comparing the dominant polymorphism state between adjacent clades (Fig. 2B), while parallel mutation was found when a variant was observed on multiple tree trunks (Fig. 2C). The performance (Fig. 3) of detecting fixed mutations is tested on an influenza A H3N2 antigenic drifting dataset [1]. For visualization, sitePath provides functions based on the R package ggtree [8]. As an example, a ZIKA virus dataset (see Additional file 1 for NCBI Accessions) is included in sitePath package. The result of its site 139 of the polyprotein, which was reported to be associated with enhanced virulence [2], is shown in Fig. 1C. Moreover, sitePath was used on SARS-CoV-2 to find fixed and parallel mutations, which were found to be potentially adaptive for the virus [9].

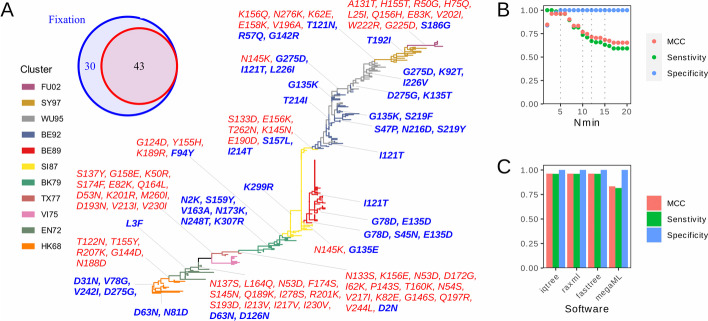

Fig. 3.

Performance evaluation of sitePath. A Recognition of fixed mutations in influenza A H3N2 with sitePath. Mutations are shown for all 43 antigenic cluster-determining sites [1] in red and an additional 30 fixed sites detected by sitePath are colored in blue. B, C Changes in specificity, sensitivity and MCC against (B) and different phylogenetic tree-estimating software (C)

Computation time complexity

Tree trunk and clade identification approximately share the same algorithm time complexity of , where is the total number of sequences and is the length of the sequence alignment. To save time, the sites that are completely conserved or have too many ambiguous characters or gaps are ignored.

Results

Performance of sitePath finding fixed mutations

We tested sitePath on an influenza A H3N2 dataset with fixed mutations, which matches the antigenic shift of the virus [1]. In this dataset, 43 fixed mutations were identified as antigenic-determined sites based on experimental work. All 43 fixed mutations in Smith et al.’s work were detected by sitePath. An extra set of 30 previously unreported fixed mutations was found (Fig. 3A). Note that these 30 additional mutations occurred in inter- or intra-antigenic clusters, which may explain why these mutations were not listed in Smith et al.’s report.

The robustness of sitePath against the sole parameter was also tested using Smith et al.’s dataset. Specificity, sensitivity and MCC (Matthews Correlation Coefficient) are relatively high for smaller values (Fig. 3B). Sensitivity and MCC decrease with higher values because the thresholds were too strict for sitePath to identify smaller clades. The impact of different tree-estimating software, including IQ-TREE [10], FastTree [11], and RaxML [12] was also tested. They were all set to use the GTR substitution model with the GAMMA model of rate heterogeneity for MLE (Maximum Likelihood Estimation) method. Sensitivity, specificity and MCC were stable, reaching 0.95, 1 and 0.95 respectively for all three software (Fig. 3C). However, we also noticed that sensitivity and MCC decreased to 0.8 for MEGAX [13]. The models for other software were not available for the MLE method of MEGAX, and the JTT substitution model was used instead. The tree topology inferred by MEGAX partly disagrees with the antigenic cluster. A few fixed mutations were not dominant in the clade because of the topology disagreement, hence missed by sitePath as true positive. The source code for the performance test can be found at https://github.com/wuaipinglab/sitePath_assessment.

Conclusions

To summarize, sitePath is a tool that attempts to cluster adjacent sequences on the phylogenetic tree using polymorphism per site per tree trunk. The branch-and-bound-like search method is used to minimize the polymorphism state across the clusters. The clustering result can be used to detect mutations with fixation or parallel patterns on the phylogenetic tree and all the results can be visualized accordingly.

The application of sitePath in viral sequences has been fully tested. In theory, sitePath could also be used in data sets with complex genomes such as prokaryotic and eukaryotic sequences. The computational consumption of dealing with complex sequences could also benefit from the neglect of conserved sites. However, considering the large size and more complex functional complexity of prokaryotic and eukaryotic sequences, it is better to apply sitePath in specific gene segments rather than the whole genomes.

Availability and requirements

Project name: sitePath

Project home page: https://github.com/wuaipinglab/sitePath

Operating systems: Cross-platform

Programming language: R, C++

License: MIT License

Any restrictions to use by non-academics: License needed

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: NCBI Accession for the ZIKA virus dataset.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Author contributions

CJ designed the work and created the software used in the work and drafted the manuscript. NH and RY collected the raw sequence data. NH and YC analyzed and prepared the data for the software. JS and SW helped interpret the data and result. H-YZ and AW conceptualized and designed the work and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program [2021YFC230130]; the CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences [2021-I2M-1-061]; the National Natural Science Foundation of China [92169106]; the special research fund for central universities, Peking Union Medical College [2021-PT180-001]; China postdoctoral science foundation grants [2019M660548, 2020T130007ZX]; the Suzhou Science and Technology Development Plan [szs2020311]; the Youthful Teacher Project of Peking Union Medical College [3332019114]; and the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province [BK20220278]. No funding body played any roles in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The sequences for ZIKA virus is publicly available at NCBI protein database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/protein/) and the accession numbers can be found in Additional file 1. The dataset used for the performance test is available from Smith et al.’s [1] study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Hang-Yu Zhou, Email: zhy@ism.cams.cn.

Aiping Wu, Email: wap@ism.cams.cn.

References

- 1.Smith DJ, Lapedes AS, de Jong JC, Bestebroer TM, Rimmelzwaan GF, Osterhaus AD, et al. Mapping the antigenic and genetic evolution of influenza virus. Science. 2004;305(5682):371–376. doi: 10.1126/science.1097211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yuan L, Huang XY, Liu ZY, Zhang F, Zhu XL, Yu JY, et al. A single mutation in the prM protein of Zika virus contributes to fetal microcephaly. Science. 2017;358(6365):933–936. doi: 10.1126/science.aam7120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Dorp L, Acman M, Richard D, Shaw LP, Ford CE, Ormond L, et al. Emergence of genomic diversity and recurrent mutations in SARS-CoV-2. Infect Genet Evol. 2020;83:104351. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2020.104351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ragonnet-Cronin M, Hodcroft E, Hue S, Fearnhill E, Delpech V, Brown AJ, et al. Automated analysis of phylogenetic clusters. BMC Bioinform. 2013;14:317. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-14-317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Han AX, Parker E, Scholer F, Maurer-Stroh S, Russell CA. Phylogenetic clustering by linear integer programming (PhyCLIP) Mol Biol Evol. 2019;36(7):1580–1595. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msz053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Menardo F, Loiseau C, Brites D, Coscolla M, Gygli SM, Rutaihwa LK, et al. Treemmer: a tool to reduce large phylogenetic datasets with minimal loss of diversity. BMC Bioinform. 2018;19(1):164. doi: 10.1186/s12859-018-2164-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li W, Godzik A. Cd-hit: a fast program for clustering and comparing large sets of protein or nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics. 2006;22(13):1658–1659. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yu G, Smith DK, Zhu H, Guan Y, Lam TT-Y. ggtree: an r package for visualization and annotation of phylogenetic trees with their covariates and other associated data. Methods Ecol Evol. 2017;8(1):28–36. doi: 10.1111/2041-210X.12628. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ji CY, Han N, Cheng YX, Shang J, Weng S, Yang R, et al. Detecting potentially adaptive mutations from the parallel and fixed patterns in SARS-CoV-2 evolution. Viruses. 2022;14(5):1087. doi: 10.3390/v14051087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nguyen L-T, Schmidt HA, Von Haeseler A, Minh BQ. IQ-TREE: a fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol Biol Evol. 2015;32(1):268–274. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msu300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Price MN, Dehal PS, Arkin AP. FastTree: computing large minimum evolution trees with profiles instead of a distance matrix. Mol Biol Evol. 2009;26(7):1641–1650. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msp077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stamatakis A. RAxML-VI-HPC: maximum likelihood-based phylogenetic analyses with thousands of taxa and mixed models. Bioinformatics. 2006;22(21):2688–2690. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kumar S, Stecher G, Li M, Knyaz C, Tamura K. MEGA X: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol Biol Evol. 2018;35(6):1547. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msy096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: NCBI Accession for the ZIKA virus dataset.

Data Availability Statement

The sequences for ZIKA virus is publicly available at NCBI protein database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/protein/) and the accession numbers can be found in Additional file 1. The dataset used for the performance test is available from Smith et al.’s [1] study.