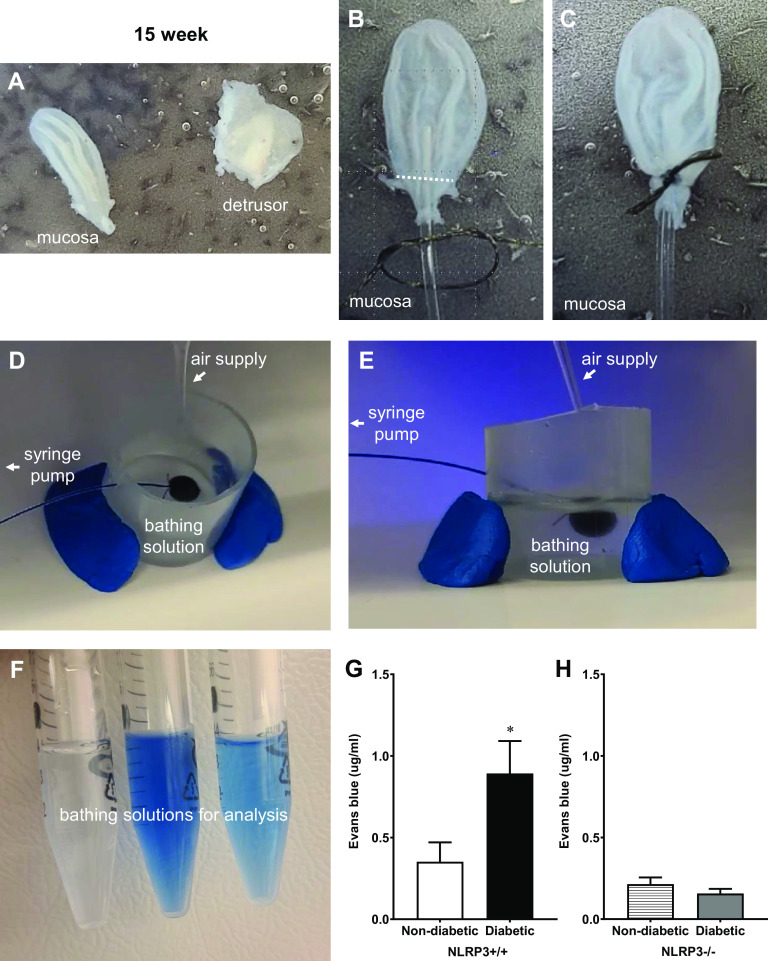

Figure 1.

Diabetes increases ex vivo urothelial permeability to Evans blue dye at the 15-wk (overactive detrusor) time point through NOD-, LRR-, and pyrin domain-containing protein 3 (NLRP3)-dependent mechanisms. Representative images are shown to illustrate key steps in this procedure and are described in further detail within methods. A: detrusors were carefully removed from intact mucosal layers. B and C: the white dotted line indicates the region proximal to ureters where the suture was tied. D and E: images of a urothelial “balloon” inflated with Evans blue dissolved in Krebs solution are shown from two angles to illustrate the spacial relationship of the air supply, syringe pump, and bathing solution. F: after the balloons remained inflated for 30 min, bathing solutions from three individual samples were collected and are shown here prior to spectrophotometrical analysis. Barrier damage was identified by leakage of Evans blue dye through the mucosal layer and into the bathing solution. G: at the overactive 15-wk time point, significantly more Evans blue permeated the bladder mucosal layers isolated from diabetic NLRP3+/+ mice compared with nondiabetic NLRP3+/+ mice. H: in mice lacking the NLRP3 gene, Evans blue permeation was not significantly different between diabetic and nondiabetic mice. n = 6, 8, 4, and 6 animals, respectively. *P < 0.05 vs. nondiabetic control mice (Student’s t test).