Abstract

Objective

To evaluate associations between visual impairment, anxiety, and depression during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States.

Design

Retrospective cross-sectional design.

Methods

This study included a cohort of U.S. adults enrolled in the National Institutes of Health All of Us Research Program. Individuals who were blind/visually impaired (BVI) were identified via Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine (SNOMED) codes and compared with a control cohort. Prevalences of baseline, new, and worsened depression and anxiety, as defined by SNOMED codes and medication use, were compared between the 2 groups. Anxiety and depression during the COVID-19 pandemic were evaluated using the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7 and the Patient Health Questionnaire 9 surveys, respectively.

Results

A total of 324,915 participants (7526 BVI individuals and 317,389 control individuals) were included. BVI individuals had higher prevalences of baseline anxiety and depression (50.4% vs 28.7%; p < 0.001), new anxiety and depression (0.98% vs 0.66%; p < 0.001), and worsened anxiety and depression throughout the COVID-19 pandemic (0.19% vs 0.07%; p < 0.001) compared with control individuals. Being BVI was significantly associated with baseline and worsened anxiety and depression after controlling for age, sex, race, ethnicity, and comorbidity (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] = 1.61; 95% CI, 1.46–1.78 and aOR = 2.07; 95% CI, 1.03–4.13). Similarly, being BVI was associated with a 2.07 point increase on the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7 survey (adjusted β = 2.07; 95% CI, 1.32–3.27) and a 2.96 point increase on the Patient Health Questionnaire 9 survey (adjusted β = 2.96; 95% CI, 1.64–5.36).

Conclusions

These findings indicate that BVI individuals were disproportionately affected by anxiety and depression at baseline and throughout the pandemic, highlighting an important need to promote access to mental health services among this population.

The response to the COVID-19 pandemic, including the government-enforced quarantine, the suspension of nonessential activities, and restrictions on social gatherings, has significantly affected the way people interact.1 , 2 Previous research demonstrates the detrimental effects of shelter-in-place orders for all individuals but particularly for older people, who may experience greater barriers to technology-based social interactions. Those with visual impairment also have been identified as vulnerable to isolation because of their unique challenges, including difficulties in accessing care or using video-based technology.3 Among people with visual impairment, loneliness during the COVID-19 pandemic has been found to be more prevalent compared with individuals without visual impairment.4

Prior studies focused on the mental health effect of the COVID-19 pandemic for people with visual impairment are few in number, include relatively small sample sizes, and are limited in diversity among studied groups.4 , 5 The All of Us Research Program currently provides the largest and most diverse American research database, with >50% of participants belonging to racial and ethnic minorities.6

In this study, we aim to evaluate the associations between visual impairment, depression, and anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic. The All of Us data set confers the unprecedented advantages of a large, multisite sample and the ability to explore associations within historically understudied racial and ethnic groups. Chief among our aims is to investigate whether or not minority groups are disproportionately affected, given the known increased prevalence and severity of COVID-19 in minority racial groups7 and documented disparities observed for a wide range of health outcomes.8 Improving our understanding of the longitudinal COVID-19 experience of people with visual impairment is an important step toward addressing inequality if individuals with visual impairment suffer disproportionately, which highlights a broader need to promote equality in access to care and mental health services.2

Methods

Study sample

All of Us. The National Institutes of Health All of Us Research Program (AoU) data set was used for analysis.5 AoU is a national database emphasizing enrolment of participants traditionally underrepresented in biomedical research. The data set contains sociodemographic information, electronic health record information (including diagnoses and drug prescriptions), and survey data for 331,360 participants as of November 29, 2021. The institutional review boards for AoU have approved all study procedures. All participants provided written informed consent. Further details can be found at the AoU Research Program Protocol (allofus.nih.gov/about/all-us-research-program-protocol).

Blind/visual impairment cases and controls. Participants who are blind/visually impaired (BVI) were identified if they met 1 of the following criteria: (i) Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine (SNOMED) diagnosis codes for “blindness/low vision” (SNOMED 4023110); (ii) responded “yes” to survey question, “Are you blind or have serious difficulty seeing, even when wearing glasses?”; and (iii) responded “yes” to survey question, “Has a doctor ever told you that you have blindness?”. Participants who served as control individuals were identified if they met all the following criteria: (i) no SNOMED codes for “blindness/low vision” (SNOMED 4023110) or “eye/vision finding” (SNOMED 4038502); (ii) responded “no” to survey question, “Are you blind or have serious difficulty seeing, even when wearing glasses?”; and (iii) responded “no” to survey question, “Has a doctor ever told you that you have: blindness?”.

Previous history of COVID-19. Participants with a previous history of COVID-19 infection were identified if they met the following criteria: (i) SNOMED diagnosis code for “COVID-19” (SNOMED 37311061) or (ii) responded “yes” to survey question, “Do you think you have had COVID-19?”.

Outcomes: anxiety and depression. Anxiety and depression were measured in several ways to better understand the effect of COVID-19 on mood disorder outcomes. Baseline anxiety/depression was defined as a diagnosis for anxiety (SNOMED 441542) or depression (SNOMED 440383) or a prescription for anxiolytics or antidepressants prior to March 30, 2020. New anxiety/depression was defined as a diagnosis for anxiety or depression or a prescription for anxiolytics or antidepressants after March 30, 2020, without baseline anxiety/depression. Worsened anxiety/depression was defined as a new SNOMED code for anxiety or depression in individuals with baseline anxiety/depression.

COVID-19 Participant Experience (COPE) is a survey administered by AoU starting in May 2020 to participants to better understand the effect of COVID-19 on participant mental and physical health. The survey included questions on social distancing experiences, vaccine perceptions, COVID-19-related effects, and anxiety and mood. At time of the analysis, >100,000 unique participants had completed this survey at least once. Symptoms related to anxiety were assessed with the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7 (GAD-7) survey, a 7-question survey that corresponds to Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, criteria for anxiety in the past 2 weeks.9 Questions assessing frequency of anxiety symptoms are answered on a 4-point scale from “Not at all” (0 points) to “Several days” (1 point), “More than half the days” (2 points), and “Nearly every day” (4 points). The points are summed, and a total score greater than the cut-off of 10 indicates severe anxiety. Symptoms related to depression were assessed with the Patient Health Questionnaire 9 (PHQ-9) survey, a 9-question survey that corresponds to Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, criteria for depression in the past 2 weeks.10 Questions assessing frequency of depressive symptoms are answered on a 4-point scale, from “Not at all” (0 points) to “Several days” (1 point), “More than half the days” (2 points), and “Nearly every day” (4 points). The points are summed, and a total score greater than the cut-off of 10 indicates severe depression.

Statistical analysis

Analyses were performed using RStudio (Posit, PBC, Boston, Mass.) on a cloud-based Jupyter Notebook environment provided by All of Us. Descriptive statistics were calculated for demographic characteristics. Differences in prevalence of outcomes across groups were compared using χ 2 tests. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression models controlled for age, sex, race, and ethnicity, and a modified Charlson comorbidity index11 was used to evaluate the associations between BVI with baseline, new, and worsened anxiety and depression. Univariate and multivariate mixed-effects logistic regression models controlling for the same covariates as above were used to evaluate the association between BVI with COPE-defined anxiety and depression and to control for participants who completed the survey more than once. Similarly, univariate and multivariate mixed-effects linear regression models controlling for the same covariates as above were used to evaluate the association between BVI with GAD-7 and PHQ-9 survey scores. Values of p <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Cohort characteristics

A total of 324,915 participants (7526 BVI individuals and 317,389 control individuals) were included in the analyses (Table 1 ). Those who were blind and visually impaired were, on average, older (58.8 ± 15.4 years vs 54.1 ± 16.8 years; p < 0.001), with a greater proportion of males (40.2% vs 38.1%; p < 0.001), black individuals (29.4% vs 20.8%; p < 0.001), and Hispanic or Latino individuals (26.2% vs 18.2%; p < 0.001). BVI individuals also had a higher comorbidity index (2.54 ± 2.29 vs 2.30 ± 2.05; p < 0.001) and were more likely to have previously contracted COVID-19 (17.4% vs 11.5%; p < 0.001).

Table 1.

Cohort characteristics.

| Characteristic | Control, n = 317,389 | Blind/visually impaired, n = 7526 | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y, n (%) | 54.1 (16.8) | 58.8 (15.4) | <0.001 | |

| Sex | Male | 38.1% | 40.2% | <0.001 |

| Female | 60.1% | 58.1% | ||

| Other | 1.18% | 1.93% | ||

| Race | Asian | 3.41% | 1.63% | <0.001 |

| Black | 20.8% | 29.4% | ||

| White | 54.3% | 39.1% | ||

| Other | 21.4% | 29.9% | ||

| Ethnicity | Hispanic or Latino | 18.2% | 26.2% | <0.001 |

| Non-Hispanic or Latino | 78.9% | 70.3% | ||

| Other | 2.9% | 3.53% | ||

| Comorbidity index | 2.30 (2.05) | 2.54 (2.29) | <0.001 | |

| COVID-19 | Contracted COVID-19 | 11.5% | 17.4% | <0.001 |

| Did not contract COVID-19 | 88.5% | 82.6% | ||

Baseline, new, and worsened anxiety and depression

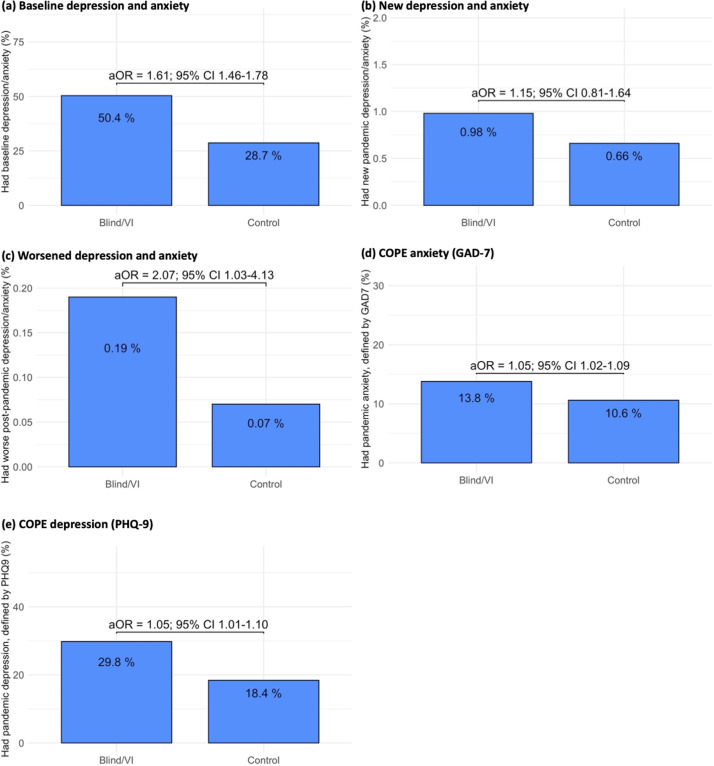

BVI individuals had a significantly higher prevalence of baseline anxiety and depression than control individuals (50.4% vs 28.7%; p < 0.001; Fig. 1 A). Individuals who contracted COVID-19 were more likely to have baseline anxiety and depression; among individuals who contracted COVID-19, 69.4% of BVI individuals had baseline anxiety and depression compared with 37.9% of non-BVI individuals (p < 0.001). In multivariate regression models, being BVI was associated with 1.61 times greater odds of having baseline anxiety and depression (odds ratio [OR] = 2.51; 95% CI, 2.41–2.64; p < 0.001), adjusted odds ratio [aOR] = 1.61; 95% CI, 1.46–1.78).

Fig. 1.

Association of blindness and visual impairment with COVID-19 pandemic anxiety and depression outcomes: (A) baseline depression and anxiety; (B) new depression and anxiety; (C) worsened depression and anxiety; (D) COPE anxiety (GAD-7); (E) COPE depression (PHQ-9).

Similarly, BVI individuals had a higher prevalence of new anxiety and depression during the pandemic; 0.98% of BVI individuals had new anxiety and depression compared with 0.66% of non-BVI individuals (p < 0.001; Fig. 1 B). This was true among individuals who contracted COVID-19. Among individuals who contracted COVID-19, 3.73% of BVI individuals had new anxiety and depression compared with 1.62% of non-BVI individuals (p = 0.014). In an unadjusted model, being BVI was associated with 1.50 times greater odds of having new anxiety and depression, though this relationship was not significant after controlling for age, sex, race, ethnicity, and comorbidity (OR = 1.50; 95% CI, 1.18–1.89; aOR = 1.15; 95% CI, 0.81–1.64).

Finally, there was a low prevalence of worsened anxiety and depression throughout the pandemic for both BVI individuals and control individuals. BVI individuals had a higher prevalence of worsened anxiety and depression during the pandemic compared with control individuals (0.19% vs 0.07%; p < 0.001; Fig. 1 C). Among individuals who contracted COVID-19, 0.75% of BVI individuals had worsened anxiety and depression compared with 0.20% of non-BVI individuals, though this result did not reach significance (p = 0.112). In multivariate regression models, being BVI was associated with 2.07 times greater odds of having worsened anxiety and depression (OR = 2.69; 95% CI, 1.56–4.61; aOR = 2.07; 95% CI, 1.03–4.13).

COPE survey

Of the 324,915 participants included in this analysis, 100,938 participants (1244 BVI individuals and 99,694 control individuals) had responded to the COPE survey. Of BVI individuals, 13.8% had anxiety (GAD-7) on the COPE survey compared with 10.6% of non-BVI individuals (p < 0.001; Fig. 1 D). Individuals who contracted COVID-19 were more likely to have anxiety (GAD-7). Among individuals who contracted COVID-19, 21.4% of BVI individuals had anxiety compared with 16.4% of non-BVI individuals, though this difference was not significant (p = 0.23). In multivariate regression models, being BVI was associated with 1.05 times greater odds of having anxiety (OR = 1.04; 95% CI, 1.01–1.06; aOR = 1.05; 95% CI, 1.02–1.09). Additionally, being BVI was associated with an increase of 2.07 points on the GAD-7 scale, after adjusting for the above covariates, compared with control individuals (β = 1.50; 95% CI, 1.11–2.01; adjusted β = 2.07; 95% CI, 1.32–3.27).

Similarly, 20.8% of BVI individuals had depression (PHQ-9) on the COPE survey compared with 18.4% of non-BVI individuals (p = 0.03; Fig. 1 E). Individuals who contracted COVID-19 were more likely to have depression (PHQ-9). Among individuals who contracted COVID-19, 27.1% of BVI individuals had depression compared with 24.4% of non-BVI individuals, though this difference was not significant (p = 0.629). In multivariate regression models, being BVI was associated with 1.05 times greater odds of having depression (OR = 1.03; 95% CI, 1.00–1.06; aOR = 1.05; 95% CI, 1.01–1.10). Additionally, being BVI was associated with an increase of 2.96 points on the PHQ-9 scale, after adjusting for the above covariates, compared with control individuals (β = 1.71; 95% CI, 1.17–2.52; adjusted β = 2.96; 95% CI, 1.64–5.36).

Effect of race and ethnicity

Our analysis included a high proportion of nonwhite and (or) Hispanic or Latino individuals (Table 1). White individuals who were BVI had higher rates of baseline anxiety and depression (58.0%) than black individuals (44.5%) and Asian individuals (27.6%). Similarly, non-Hispanic or Latino BVI individuals had higher rates of baseline anxiety than Hispanic or Latino BVI individuals (52.0% vs 45.9%). However, in all race/ethnicity groups, BVI individuals had higher rates of baseline anxiety and depression (Table 2 ). Black BVI individuals had the highest rates of new anxiety and depression (1.09%), closely followed by white BVI individuals (1.05%). All race/ethnicity groups except for Asian individuals had higher rates of new anxiety/depression among BVI individuals (Table 3 ). For worsened anxiety/depression, white BVI individuals had the highest rates (0.31%), followed by black BVI individuals (0.09%). All race/ethnicity groups except for Asian individuals had higher rates of worsened anxiety/depression among BVI individuals (Table 4 ).

Table 2.

Baseline anxiety and depression among racial and ethnic subgroups.

| Race/ethnicity | Blind/visually impaired | Control | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race | White | 58.0% | 31.1% | <0.001 |

| Black | 44.5% | 27.6% | <0.001 | |

| Asian | 38.2% | 13.6% | <0.001 | |

| Ethnicity | Hispanic or Latino | 45.9% | 25.4% | <0.001 |

| Non-Hispanic or Latino | 52.0% | 29.4% | <0.001 | |

Table 3.

New anxiety and depression among racial and ethnic subgroups.

| Race/ethnicity | Blind/visually impaired | Control | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race | White | 1.05% | 0.65% | 0.009 |

| Black | 1.09% | 0.70% | 0.045 | |

| Asian | 0.00% | 0.53% | 1.00 | |

| Ethnicity | Hispanic or Latino | 0.96% | 0.70% | 0.223 |

| Non-Hispanic or Latino | 1.00% | 0.65% | 0.002 | |

Table 4.

Worsened anxiety and depression among racial and ethnic subgroups.

| Race/ethnicity | Blind/visually impaired | Control | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race | White | 0.31% | 0.07% | <0.001 |

| Black | 0.09% | 0.08% | 0.686 | |

| Asian | 0% | 0.06% | 1.00 | |

| Ethnicity | Hispanic or Latino | 0.20% | 0.07% | 0.065 |

| Non-Hispanic or Latino | 0.19% | 0.07% | 0.005 | |

Of the 100,938 participants who responded to the COPE survey, 89,478 were white (1066 BVI individuals), 5296 were black (82 BVI individuals), 2803 were Asian (13 BVI individuals), and the remainder were categorized as “Other.” A total of 95,064 individuals were non-Hispanic or Latino (1154 BVI individuals), 6273 were Hispanic or Latino (121 BVI individuals), and the remainder were categorized as “Other.” White BVI individuals had the highest rates of anxiety (GAD-7; 13.5%), followed by black individuals (10.7%) and Asian individuals (0%). Hispanic or Latino individuals had higher rates of anxiety (GAD-7) than non-Hispanic or Latino BVI individuals (21.6% vs 13.0%). With the exception of Asian individuals, all race/ethnicity groups had higher rates of anxiety among BVI individuals, though this was only statistically significant for white and non-Hispanic or Latino individuals (Table 5 ). Similarly, White BVI individuals had the highest rates of depression (PHQ-9; 19.9%), followed by black individuals (19.7%) and Asian individuals (0%). Hispanic or Latino individuals had higher rates of depression (PHQ-9) than non-Hispanic or Latino BVI individuals (29.9% vs 19.8%). All BVI individuals of different races/ethnicities had higher rates of depression except Asian individuals, though this did not reach statistical significance in subgroup analysis (Table 6 ).

Table 5.

COPE survey GAD-7 anxiety among racial and ethnic subgroups.

| Race/etnicity | Blind/visually impaired | Control | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race | White | 13.5% | 10.0% | <0.001 |

| Black | 10.7% | 12.9% | 0.697 | |

| Asian | 0% | 12.1% | 0.381 | |

| Ethnicity | Hispanic or Latino | 21.6% | 16.2% | 0.154 |

| Non-Hispanic or Latino | 13.0% | 10.2% | 0.003 | |

GAD-7, Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7

Table 6.

COPE survey PHQ-9 depression among racial and ethnic subgroups.

| Race/ethnicity | Blind/visually impaired | Control | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race | White | 19.9% | 17.8% | 0.090 |

| Black | 19.7% | 19.6% | 1.00 | |

| Asian | 0% | 19.2% | 0.139 | |

| Ethnicity | Hispanic or Latino | 29.9% | 24.8% | 0.252 |

| Non-Hispanic or Latino | 19.8% | 18.0% | 0.127 | |

PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire 9

Discussion

In this large study of All of Us participants, we found a higher likelihood of electronic health record–defined baseline, new, and worsened anxiety/depression during the COVID-19 pandemic among individuals who are blind and (or) visually impaired. We also demonstrate higher levels of self-reported anxious and depressive symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic among individuals who are blind and (or) visually impaired. Together these findings indicate that individuals with visual impairment were suffering disproportionately throughout the pandemic and highlight an important need to promote access to mental health services among this population.

We found that more than 1 in 2 BVI individuals had anxiety or depression compared with 1 in 4 control individuals. Our results are in agreement with previous studies reporting higher rates of anxiety and depression among individuals with visual impairment. In a large meta-analysis, Parravano et al. 12 found that 1 in 4 patients with visual impairment were affected by depression. Ulhaq et al.13 reported a 31.2% pooled prevalence of anxiety symptoms among patients with ophthalmic diseases and a twofold increase in the prevalence of anxiety symptoms and disorders compared with healthy control individuals. Similarly, Heesterbeek et al. 14 reported that the cumulative incidence of subthreshold (e.g., early) depression and anxiety in older adults with visual impairment was twice as high as in normally sighted peers.

There are several hypotheses for what may cause higher rates of mental health disorders among individuals who are visually impaired. These include difficulties adjusting to loss of functional independence and physical mobility,15 restrictions on driving,16 economic burden, and hardship,17 , 18 among others. In a study using semistructured interviews, van Munster et al.19 found that visually impaired individuals often had limited knowledge about mental health, potentially due to lower ability to obtain processable information and thus lower mental health literacy.19 They also found that health care providers did not always provide resources for BVI individuals to access mental health services; indeed, only 25% of ophthalmic and low-vision service workers provide depression screening.20

It may come as no surprise that this study found higher rates of new and worsened anxiety and depression, as well as higher scores on the GAD-7 and PHQ-9 surveys, throughout the COVID-19 pandemic among individuals who are blind or visually impaired. The early days of the COVID-19 pandemic were met with a series of responses including lockdowns and social restrictions to limit the spread of disease. Higher rates of anxiety and depression throughout the pandemic in the general population have been widely reported globally.21, 22, 23, 24 Individuals who are BVI are at higher risk of depression and anxiety and were disproportionately affected by the pandemic. There may be several factors at play, including increased loneliness (potentially due to difficulties transitioning to virtual social interactions) 4 and difficulties adhering to social distancing and hygiene protocols to prevent COVID-19 transmission.5 Furthermore, access to appropriate health care services may have decreased throughout the COVID-19 pandemic; one study found that only 59.3% of patients completed all scheduled eye care visits during the pandemic compared with 82.0% of patients before the pandemic. These missed eye care visits may have provided an opportunity for earlier mental health screening and referral to evaluate and treat anxiety and depression.25

Our study also found that BVI individuals who contracted COVID-19 were more likely to have higher rates of both baseline and new anxiety and depression than non-BVI individuals. This finding may demonstrate a cyclic relationship where BVI individuals are both more susceptible to anxiety and depression after a COVID-19 infection and more susceptible to COVID-19 infection when they have concomitant anxiety and depression. Reasons for increased susceptibility to anxiety and depression after a COVID-19 infection have been discussed previously and may include increased loneliness and difficulties adhering to hygiene protocols. Increased susceptibility to COVID-19 infection in individuals who have anxiety or depression has been demonstrated previously; it is posited that mental health conditions at large have been linked to elevated risk of other comorbidities and decreased levels of self-care, thereby increasing the risk of COVID-19 infection.26 Our findings show that this risk is disproportionately high in individuals who are blind and visually impaired.

Finally, our study found that in all races and ethnicities, individuals who are BVI had higher rates of baseline as well as new and worsened anxiety and depression during the pandemic (with the exception of Asian individuals). We also report higher rates of all anxiety and depression outcomes among white BVI populations compared with black and Asian individuals. Prior research has demonstrated higher levels of anxiety and depression among white individuals.27 , 28 This may be due in part to disparities in health care access in addition to social stigma regarding mental health in certain cultures. Disparities in access to mental health care have been well documented, with white individuals receiving higher levels of mental health care, outpatient care, and psychotropic medication prescriptions compared with their black and Hispanic counterparts.29 Other potential explanations of disparity in diagnosis rates may include a strong sense of ethnic identity and greater religious and community support among minority groups.30 However, studies also have found that though black individuals may have lower rates of depression, those who are diagnosed with depression tend to have more severe and chronic disease, underscoring the importance of adequately connecting individuals with appropriate medical services and care.30 While Hispanic or Latino BVI individuals had lower rates of baseline, new, and worsened anxiety and depression than non-Hispanic or Latino individuals, they had higher rates of COPE survey anxiety and depression. This may reflect a higher level of unmet mental health needs during the pandemic that were not formally diagnosed or pharmacologically treated among Hispanic or Latino BVI individuals.

This study has many notable strengths. We use a large and comprehensive national database to investigate the association of visual impairment with rates of anxiety and depression. Because of the high diversity of the AoU research database, we were also able to investigate the rates of anxiety and depression among historically understudied racial and ethnic groups. However, our study is also subject to some limitations. First, our definitions of BVI, anxiety, and depression relied on the use of available electronic health record data, specifically diagnosis codes, and medication use, which may not always be precise. Second, our data set did not have sufficient sample size of PHQ-9 and GAD-7 scores among understudied racial and ethnic groups, particularly Asian individuals; such data may allow for identification of anxious and depressive symptoms among individuals who may not have access to health care resources and thus may not be represented in the electronic health record. Further research in historically understudied visually impaired populations may better identify and quantify differences in mental health outcomes among these populations. Finally, while the AoU research database confers a large sample size, we were unable to assess the relationship of individual ophthalmologic diseases (e.g., glaucoma, age-related macular degeneration) to COVID-19-related anxiety and depression due to an insufficient sample of individuals with these ophthalmologic diseases and COVID-19 survey responses. Furthermore, the AoU database does not include measures of visual impairment severity levels, so we were unable to analyze whether the degree of visual impairment had an influence on anxiety and depression levels.

In summary, here we demonstrate that BVI individuals are disproportionately affected by anxiety and depression at baseline and throughout the COVID-19 pandemic compared with their non–visually impaired peers. These findings underscore the importance of equity in access to care and mental health services for individuals with visual disabilities. Further research about how to best support mental health outcomes in visually impaired individuals as the COVID-19 pandemic continues should be prioritized.

Acknowledgments

Footnotes and Disclosure

The authors have no proprietary or commercial interest in any materials discussed in this article.

Funding

This work was supported in part by a National Institutes of Health (NIH) K23 Career Development Award (K23EY032634) (N.Z.), NIH R21 Exploratory/Developmental Research Grant Award (1R21EY032953), and Research to Prevent Blindness Career Development Award (N.Z.).

References

- 1.Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 2020;395:912–920. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Razai MS, Oakeshott P, Kankam H, Galea S, Stokes-Lampard H. Mitigating the psychological effects of social isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMJ. 2020;369:m1904. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ting DSJ, Krause S, Said DG, Dua HS. Psychosocial impact of COVID-19 pandemic lockdown on people living with eye diseases in the UK. Eye (Lond) 2021;35:2064–2066. doi: 10.1038/s41433-020-01130-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heinze N, Hussain SF, Castle CL, Godier-McBard LR, Kempapidis T, Gomes RSM. The long-term impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on loneliness in people living with disability and visual impairment. Front Public Health. 2021;9 doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.738304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shalaby WS, Odayappan A, Venkatesh R, et al. The impact of COVID-19 on individuals across the spectrum of visual impairment. Am J Ophthalmol. 2021;227:53–65. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2021.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.All of Us Research Program Investigators. Denny JC, Rutter JL, et al. The “All of Us” Research Program. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:668–676. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr1809937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lopez L, Hart LH, Katz MH. Racial and ethnic health disparities related to COVID-19. JAMA. 2021;325:719–720. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.26443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weinstein JN, Geller A, Negussie Y, Baciu A. National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2017. Communities in action: Pathways to health equity. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Newman MG, Zuellig AR, Kachin KE, et al. Preliminary reliability and validity of the generalized anxiety disorder questionnaire IV: a revised self-report diagnostic measure of generalized anxiety disorder. Behav Ther. 2002;33:215–233. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Levis B, Benedetti A, Thombs BD. Depression Screening Data (DEPRESSD) Collaboration. Accuracy of Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) for screening to detect major depression: individual participant data meta-analysis. BMJ. 2019;365:l1476. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l1476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Quan H, Li B, Couris CM, et al. Updating and validating the Charlson Comorbidity Index and score for risk adjustment in hospital discharge abstracts using data from 6 countries. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173:676–682. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parravano M, Petri D, Maurutto E, et al. Association between visual impairment and depression in patients attending eye clinics: a meta-analysis. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2021;139:753–761. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2021.1557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ulhaq ZS, Soraya GV, Dewi NA, Wulandari LR. The prevalence of anxiety symptoms and disorders among ophthalmic disease patients. Ther Adv Ophthalmol. 2022;14 doi: 10.1177/25158414221090100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heesterbeek TJ, van der Aa HPA, van Rens GHMB, Twisk JWR, van Nispen RMA. The incidence and predictors of depressive and anxiety symptoms in older adults with vision impairment: a longitudinal prospective cohort study. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt. 2017;37:385–398. doi: 10.1111/opo.12388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Court H, McLean G, Guthrie B, Mercer SW, Smith DJ. Visual impairment is associated with physical and mental comorbidities in older adults: a cross-sectional study. BMC Med. 2014;12:181. doi: 10.1186/s12916-014-0181-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keay L, Munoz B, Turano KA, et al. Visual and cognitive deficits predict stopping or restricting driving: the Salisbury Eye Evaluation Driving Study (SEEDS) Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:107–113. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-2367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Demmin DL, Silverstein SM. Visual impairment and mental health: unmet needs and treatment options. Clin Ophthalmol. 2020;14:4229–4251. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S258783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jin Y, Lin D, Dai ML, et al. Economic hardship, ocular complications, and poor self-reported visual function are predictors of mental problems in patients with uveitis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2021;29:1045–1055. doi: 10.1080/09273948.2020.1770297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Munster EPJ, van der Aa HPA, Verstraten P, van Nispen RMA. Barriers and facilitators to recognize and discuss depression and anxiety experienced by adults with vision impairment or blindness: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21:749. doi: 10.1186/s12913-021-06682-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rees G, Fenwick EK, Keeffe JE, Mellor D, Lamoureux EL. Detection of depression in patients with low vision. Optom Vis Sci. 2009;86:1328–1336. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0b013e3181c07a55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pashazadeh Kan F, Raoofi S, Rafiei S, et al. A systematic review of the prevalence of anxiety among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Affect Disord. 2021;293:391–398. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.06.073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Salari N, Hosseinian-Far A, Jalali R, et al. Prevalence of stress, anxiety, depression among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Global Health. 2020;16:57. doi: 10.1186/s12992-020-00589-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shi L, Lu ZA, Que JY, et al. Prevalence of and risk factors associated with mental health symptoms among the general population in China during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.14053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Castaldelli-Maia JM, Marziali ME, Lu Z, Martins SS. Investigating the effect of national government physical distancing measures on depression and anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic through meta-analysis and meta-regression. Psychol Med. 2021;51:881–893. doi: 10.1017/S0033291721000933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brant AR, Pershing S, Hess O, et al. The impact of COVID-19 on missed ophthalmology clinic visits. Clin Ophthalmol. 2021;15:4645–4657. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S341739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang Y, Yang Y, Ren L, Shao Y, Tao W, jian Dai X. Preexisting mental disorders increase the risk of COVID-19 infection and associated mortality. Front Public Health. 2021;9 doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.684112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blanco C, Rubio J, Wall M, Wang S, Jiu CJ, Kendler KS. Risk factors for anxiety disorders: common and specific effects in a national sample. Depress Anxiety. 2014;31:756–764. doi: 10.1002/da.22247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Himle JA, Baser RE, Taylor RJ, Campbell RD, Jackson JS. Anxiety disorders among African Americans, blacks of Caribbean descent, and non-Hispanic whites in the United States. J Anxiety Disord. 2009;23:578–590. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cook BL, Trinh NH, Li Z, Hou SSY, Progovac AM. Trends in racial-ethnic disparities in access to mental health care, 2004–2012. Psychiatr Serv. 2017;68:9–16. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201500453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bailey R, Mokonogho J, Kumar A. Racial and ethnic differences in depression: current perspectives. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2019;15:603–609. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S128584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]