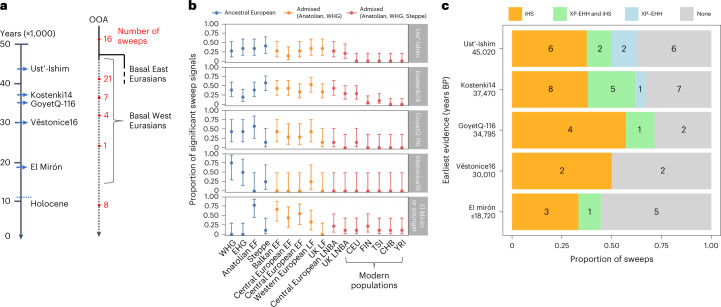

Fig. 4. Older sweeps are more robust to population admixture.

a, Schematic representation of the inferred temporal origins of the 57 sweeps. Each sweep was classified according to the first presence of the sweep haplotype amongst the five moderate-to-high-coverage Upper Palaeolithic specimens (italic labels, blue arrows indicate the approximate sample age), resulting in five distinct categories that are putative lower bounds of selection onset times: that is, Ust’-Ishim, n = 16; Kostenki14, n = 21; GoyetQ-116, n = 7; Věstonice16, n = 4; El Mirón, n = 9 (the final category also includes eight sweep haplotypes that were not observed in any Palaeolithic specimen). b,c, For each onset category, we quantified the proportion of sweeps observed for each tested population (b; dots indicate proportion of sweeps present at q < 0.05; error bars show 95% binomial confidence intervals) and classified sweeps according to results from two studies reporting partial sweeps in modern Europeans35,36 (c; integrated haplotype score, iHS; test statistics from ref. 35 being limited to outliers reported in at least two European populations to provide a stringent classification). Sweeps starting within the last 35,000 years (that is, not observed in GoyetQ-116 or older samples) tend to have patterns consistent with local selection, being highly frequent in some ancient populations but absent in others (Supplementary Text 4) and are less likely to be reported as partial sweeps nearing fixation (that is, lack an XP-EHH signal in ref. 35,36; see key in c). Although the latter difference was not significant (one-sided Fisher’s exact test P ~0.17), our results are consistent with sweeps arising after the diversification of the Eurasian founders being more susceptible to admixture distortion. CEU, Western European; Han Chinese in Beijing, CHB; FIN, Finnish in Finland; TSI, Toscani in Italy.