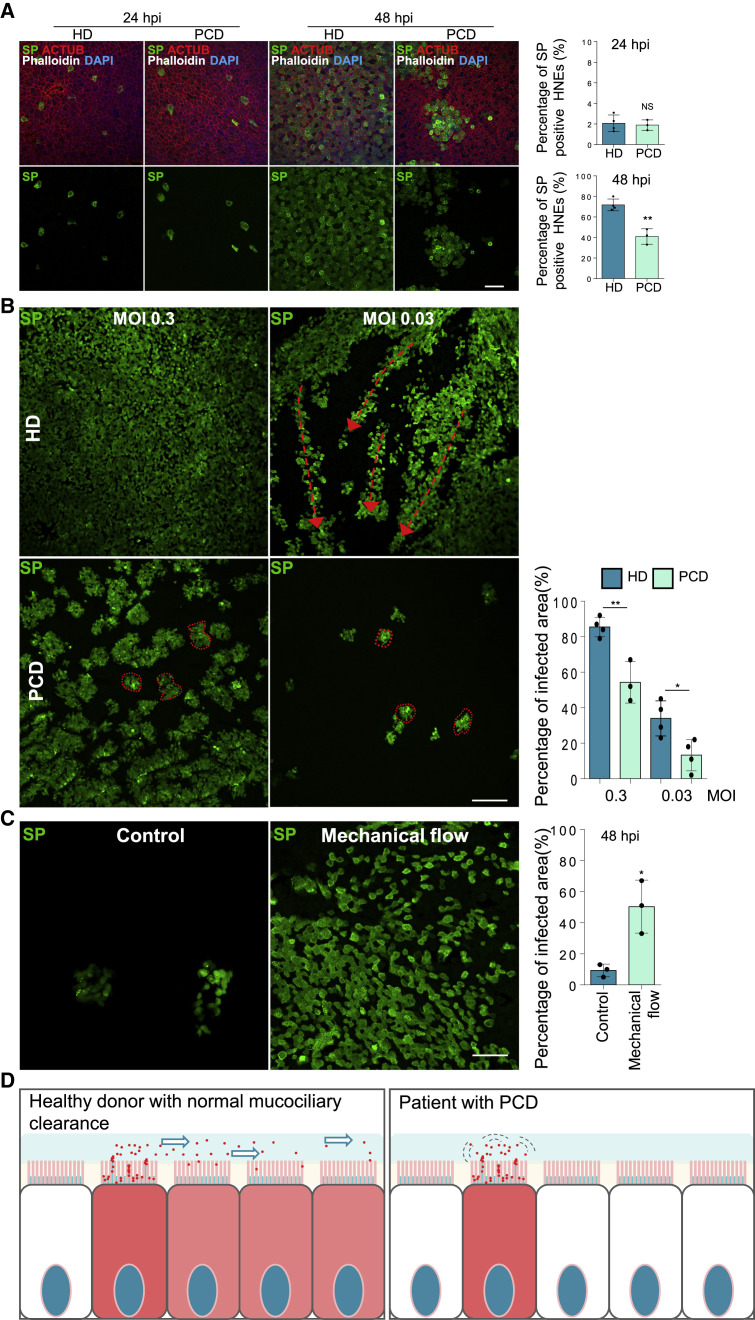

Figure 5.

Mucociliary transport assists the spread of SARS-CoV-2

(A and B) Cilia beating does not alter viral entry but affects virus spread. (A) Infected HNEs (MOI 0.3) were stained at 24 and 48 hpi. Representative IF staining of SP, ACTUB, and phalloidin in control versus PCD HNEs at 24 hpi (left image) and 48 hpi (right image). Quantified percentages of SP-positive ciliated HNEs (right panels). Error bars represent mean ± SD (3,000–4,000 HNEs were quantified from infected control (Donors 5–8) and PCD HNEs (Donors 1–3, Tables S1 and S2).

(B) Infected HNEs (MOIs 0.3, 0.03) were stained at 48 hpi. Representative IF images of SP in control (Donor 6) and PCD (PCD Donor 2) HNEs. Quantified percentages of SP-positive area (right panel). Error bars represent mean ± SD (data from Donors 5–8 and PCD Donors 1–3).

(C) The simulated mucus flow allows redistribution of virus particles. SARS-CoV-2-treated PCD HNEs were exposed or not treated to mechanical flow by pipetting 50 μL medium at24 hpi and were stained at 48 hpi. Representative IF images of SP in control (left image) and mechanical force (right image) PCD (PCD Donor 1) HNEs. Quantified percentages of SP-positive area (right panel). Error bars represent mean ± SD (PCD Donors 1–3).

(D) Model illustrating mucociliary flow effects during SARS-CoV-2 spread. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.05, NS represents not significant, two-tailed Student’s t test. Each dot represents one donor. Scale bars represent 20 μm (A), 50 μm (C), and 100 μm (B). See Figure S5 and Tables S1 and S2.