Abstract

Aims

Cardiogenic shock (CGS) occurs in 6-10% of patients with acute coronary syndromes (ACS). Mortality has fallen over time from 80% to approximately 50% consequent on acute revascularisation but has plateaued since the 1990s. Once established, patients with CGS develop adverse compensatory mechanisms that contribute to the downward spiral towards death, which becomes difficult to reverse. We aimed to test in a robust, prospective, randomised controlled trial whether early support with veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VA-ECMO) provides clinical benefit by improving mortality and morbidity.

Methods and results

The EURO SHOCK trial will test the benefit or otherwise of mechanical cardiac support using VA-ECMO, initiated early after acute percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) for CGS. The trial sets out to randomise 428 patients with CGS complicating ACS, following primary PCI (P-PCI), to either very early ECMO plus standard pharmacotherapy, or standard pharmacotherapy alone. It will be conducted in 39 European centres. The primary endpoint is 30-day all-cause mortality with key secondary endpoints: 1) 12-month all-cause mortality or admission for heart failure, 2) 12-month all-cause mortality, 3) 12-month admission for heart failure. Cost-effectiveness analysis (including quality of life measures) will be embedded. Mechanistic and hypothesis-generating substudies will be undertaken.

Conclusions

The EURO SHOCK trial will determine whether early initiation of VA-ECMO in patients presenting with ACS-CGS persisting after PCI improves mortality and morbidity.

Introduction

Cardiogenic shock (CGS) occurs in up to 10% of patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS). It has increased over time, possibly due to better organisation of pre-hospital care, ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) networks, public education and pre-hospital resuscitation. The US National Inpatient Sample Database reported that the CGS incidence rose from 6.5% to 10.1% from 2003 to 20101. The UK British Cardiovascular Intervention Society (BCIS) audit data showed an increase in primary percutaneous coronary intervention (P-PCI) in the setting of CGS (8.7% in 2015 to 9.1% in 2016)2.

CGS carries a high mortality (30-day ACS mortality with CGS is reported at 40%-50% [Supplementary Table 1] compared to 4% without CGS)3,4. Furthermore, 30% of CGS survivors develop chronic heart failure (CHF)5,6,7, with its socio-economic implications, high morbidity and poor quality of life, breathlessness, lethargy and debility. Patients carry a burden of ill health requiring admissions for decompensated heart failure, limited return to full-time activities and work, life-long medications and a potential need for expensive therapeutic devices (implantable cardioverter-defibrillator [ICD] and cardiac resynchronisation therapy [CRT])8.

CGS occurs in >50,000 patients per annum in Europe9. The unacceptably high mortality and morbidity, despite contemporary treatments, represents a true unmet clinical need. Once initiated, the pathological process in CGS can be self-perpetuating. A “spiral of decline”, difficult to halt once initiated, ultimately leads to death.

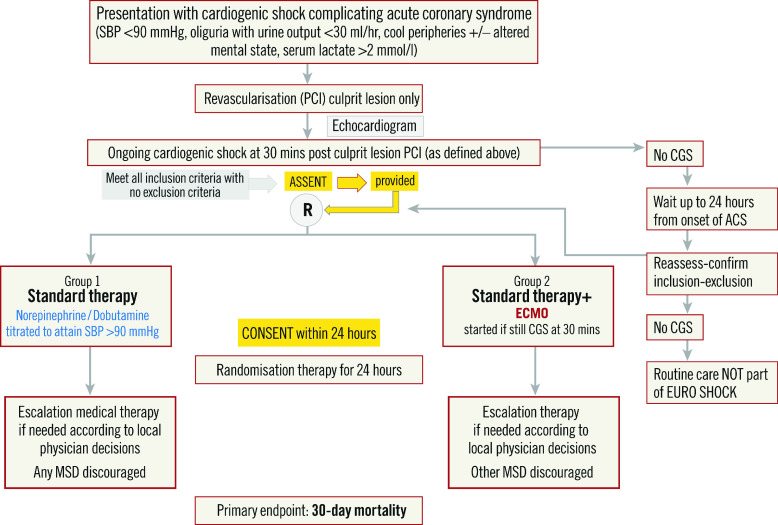

Other than culprit artery revascularisation10, no intervention has shown significant benefit, with marginal benefit from the use of norepinephrine or levosimendan (Figure 1). Most studies on the use of mechanical support devices (MSD), such as veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VA-ECMO) or heart pumps (e.g., Impella™; Abiomed, Danvers, MA, USA) have been retrospective, and included patients treated in a refractory shock state. Some non-randomised data suggest that early use of MSD may be beneficial9.

Figure 1.

The effect of assessed interventions on outcomes from cardiogenic shock. Modified from Thiele et al17.

We hypothesise that initiating support prior to adverse compensatory mechanisms will reduce mortality and morbidity. EURO SHOCK will be a robust, prospective, randomised controlled trial to test whether early support with VA-ECMO provides clinical benefit.

Methods

RATIONALE AND DESIGN OF THE EURO SHOCK TRIAL

The EURO SHOCK trial addresses whether early VA-ECMO attenuates the haemodynamic decline, reduces multi-organ failure, and so reduces mortality. It is cited as an ongoing study in the most recent position paper on cardiogenic shock11.

EURO SHOCK (NCT03813134) is a prospective, randomised, open-label, study design comparing:

Group 1. Immediate PCI + standard care (pharmacological support).

Group 2. Immediate PCI + early peripheral VA-ECMO and standard care (pharmacological support).

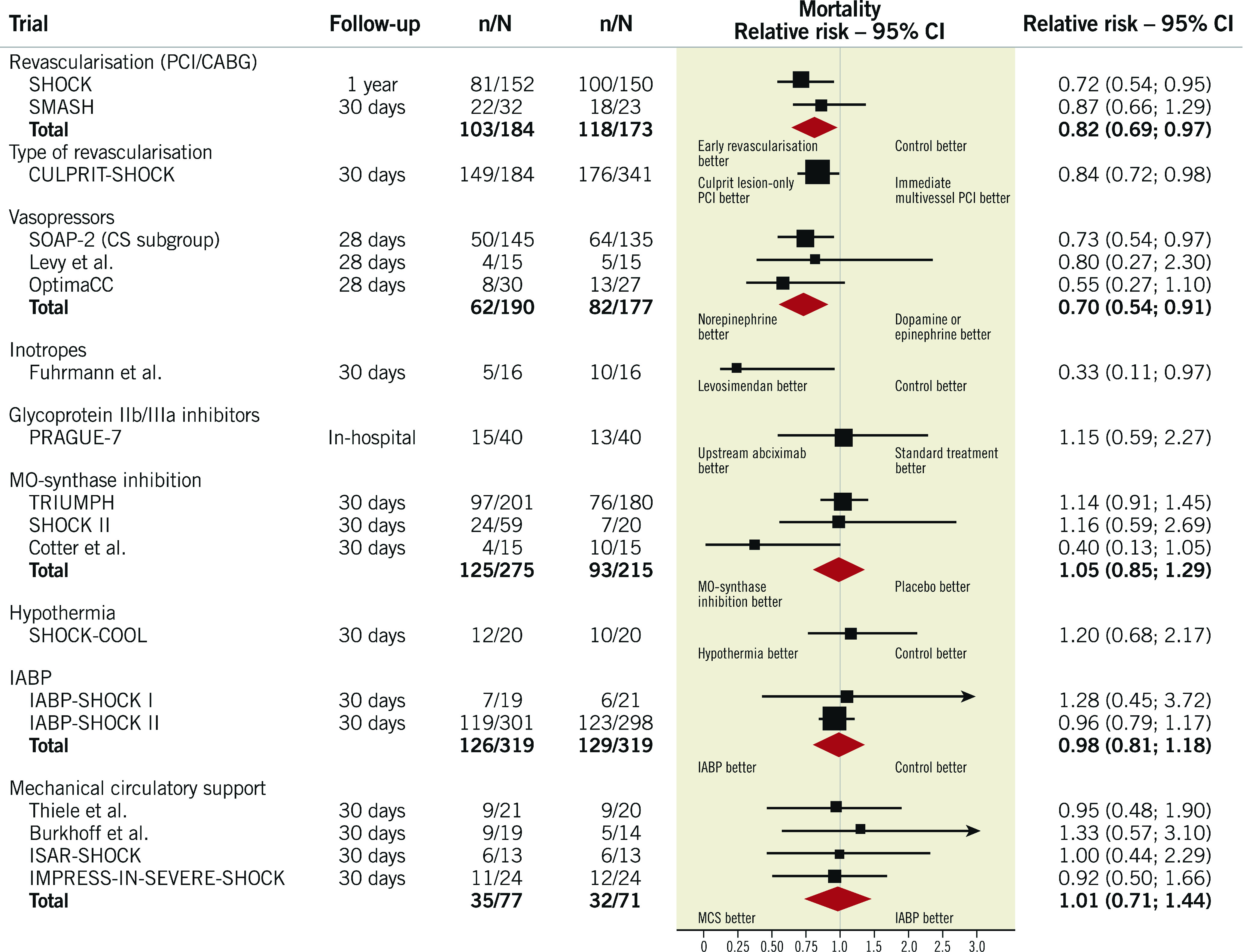

The trial flow diagram is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

EURO SHOCK trial flow diagram.

The trial hypothesis is that “Early VA-ECMO following revascularisation by PCI in patients with CGS complicating ACS reduces 30-day mortality compared with standard pharmacological support”.

The trial is organised into work packages (Supplementary Table 2).

TRIAL CANDIDATES

Patients presenting with ACS (N-STEMI/STEMI) and CGS, including those who have been expeditiously resuscitated, who undergo PCI to the infarct-related artery will be considered for EURO SHOCK, irrespective of PCI success if, after 30 minutes, CGS persists (i.e., insufficient benefit from PCI), provided echocardiography shows no significant mechanical cause (e.g., significant mitral regurgitation).

RATIONALE OF TIMING

Some registry data indicate that the earlier MSD are deployed the better. This has led to the concept that “shock-to-support” times be shortened to the point where some believe that the MSD should be deployed prior to PCI. However, clinicians involved in EURO SHOCK have all seen cases with improvement in haemodynamic parameters following revascularisation of the infarct-related artery, now supported by screening data from the EURO SHOCK trial. To avoid unnecessary, expensive and potentially harmful use of MSD, the EURO SHOCK trial will only randomise after the primary PCI has been completed, but regardless of its success or otherwise.

REASONS FOR TIMING OF MSD IN EURO SHOCK

1. We believe that initiating ECMO, if so randomised, before revascularisation would cause unacceptable delay in PCI, impacting negatively on national audit metrics (e.g., door-to-balloon times).

2. The patient’s condition can improve with PCI. Trials that randomise before P-PCI will include a lower-risk group. Those who do not improve after P-PCI (EURO SHOCK) are likely to be higher risk.

3. The time difference between pre-PCI VA-ECMO and post-PCI VA-ECMO will be significantly less than the timing of current clinical scenarios, where ECMO is frequently deployed only as bail-out after several days.

INCLUSION AND EXCLUSION CRITERIA

The trial will consider all patients presenting within 24 hours of ACS with CGS, as defined in the original SHOCK trial10. The definition of CGS for the trial will thus be:

“persistent systolic blood pressure (SBP) of <90 mmHg for at least 30 minutes, or the requirement for vasopressor or inotropic therapy to maintain SBP >90 mmHg with clinical signs of pulmonary congestion, plus signs of impaired organ perfusion with at least one of the following manifestations:

– altered mental status

– cold and clammy skin and limbs

– oliguria with a urine output of less than 30 ml per hour

– elevated arterial lactate level of >2.0 mmol per litre on admission”.

Screened patients should fulfil all inclusion with no exclusion criteria (Supplementary Table 3).

THE KEY INCLUSION CRITERIA ARE:

– Willing to provide informed consent/consultee declaration.

– Presentation with a diagnosis of CGS within 24 hours of onset of ACS symptoms.

– CGS secondary to ACS (Type 1 MI STEMI or N-STEMI) or secondary to ACS following previous recent PCI (acute/subacute stent thrombosis, ARC definition).

– Acute PCI has been attempted.

– Persistence of CGS (BP ≤90 mmHg, or need for pharmacological support to maintain BP ≥90 mmHg) assessed 30 minutes after successful or unsuccessful revascularisation of culprit coronary artery.

KEY EXCLUSION CRITERIA:

– Age <18 years and ≥90 years.

– Deemed too frail (Canadian frailty score ≥5).

– Other causes of shock.

– Severe peripheral vascular disease (precluding access and ECMO contraindicated).

– Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) under any of the following circumstances:

– without return of spontaneous circulation (ongoing resuscitation effort)

– with pH <7

– without bystander CPR within 10 minutes of collapse.

OUTCOME MEASURES

PRIMARY ENDPOINT

– The primary endpoint will be all-cause mortality at 30 days.

SECONDARY ENDPOINTS

Key secondary endpoints:

1. All-cause mortality or admission for heart failure at 12 months.

2. All-cause mortality at 12 months.

3. Admission for heart failure at 12 months.

Other secondary endpoints are shown in Supplementary Appendix 1.

SAMPLE SIZE AND POWER CALCULATIONS

Data reporting in-hospital/30-day mortality rates in CGS are summarised in Supplementary Table 1. The mean 30-day mortality rate is 46.5%.

Mortality varies according to differences in study design and definitions. Some do not include refractory CGS whereas our patients need to remain in CGS post P-PCI and consensus suggests rates of up to 50%4. On review of all data and in line with contemporary power calculations from other trials in this arena (DanGer Shock, ECLS-SHOCK), we estimate control group 30-day mortality at 50%. Furthermore, Pöss et al12 suggest that, based on six variables, there are three risk categories in the IABP-SHOCK II score. Patients in the low-, intermediate-, and high-risk categories have an in-hospital mortality risk of 20-30%, 40-60%, and 70-90%, respectively. We anticipate that patients included in the study will have at least an intermediate score, especially as only patients with persistent CGS 30 minutes post revascularisation will be included.

Some non-randomised studies indicate that VA-ECMO may reduce 30-day mortality by 30-45%13,14. A recent meta-analysis suggests a 46% reduction in mortality with VA-ECMO compared with intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP) alone15. We judge that a conservative estimate of a 25-30% reduction in 30-day mortality from early VA-ECMO would be regarded as clinically relevant and sufficient for the tested strategy to influence clinicians worldwide should the data support benefit.

Power calculations are based on an anticipated 30-day overall mortality rate of 50% in Group 1 and a 27.5% relative reduction in the primary endpoint in Group 2. To detect this difference with 80% power at a two-sided α=0.05, and anticipating a 5% withdrawal rate, 214 patients per group are required (total 428). Power calculations were performed using a log-rank test comparing two survival rates in Stata v14 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Two important studies justify our power calculations. The recent categorisation according to the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions’ (SCAI) definition clearly puts the mortality in groups C (Classic) and D (Doom) at 53.9% and 66.9%, respectively16. This is well within the range we have chosen. This is also supported by a recent update, where a figure of approximately 50% is cited17. Finally, the numbers of patients adjudged to be required by the ongoing four trials are very similar.

STUDY PROCEDURES

New section

Verbal consent will be obtained from the patient and witnessed by an independent health professional.

Patients may not have the capacity to provide informed consent in the acute CGS setting. If so, then two options will be considered, according to individual country legal agreements.

1. Declaration from a consultee (relative/friend) with specific, separate information documents.

2. Nominated consultee declaration from a physician/health professional, independent and unrelated to the trial (preferably by discussion with relatives). The local principal investigator (PI)/designated person will countersign.

If the patient recovers by 24 hours, then full consent to continue in the study, and retrospective written consent, will be obtained.

If there is no recovery at 24 hours, then consent to continue in the study will again be sought from relatives/physicians.

There are policies in place if the patient or the relatives refuse further consent or if after consent this is subsequently withdrawn.

If consent is withdrawn, only data to that point will be used in the trial.

It should be noted that consent (including verbal consent) has been approved in all countries but with differences to comply with different country laws. The major differences are in Italy where, according to Italian law (d.lgs. 211/2003), the Italian sites will not be asked to enrol unconscious patients.

RANDOMISATION

Assessment of the patient will take place up to 30 minutes after culprit lesion PCI and, irrespective of success, patients will be considered for randomisation providing there is persisting CGS. During this interim time, the ECMO team will be pre-alerted and an echocardiogram undertaken to exclude mechanical causes. A mini-multidisciplinary team (m-MDT) of those involved in patient decision making (including any of physician/interventionist, local EURO-SHOCK PI, ECMO specialist, intensivist) will determine the suitability of the patient for inclusion.

If the patient fulfils all inclusion criteria with no exclusion criteria, following verbal consent, patients will be randomised (1:1), stratified according to presentation following OHCA, to either continuing pharmacological support or immediate peripheral VA-ECMO implantation. Randomisation will be primarily by telephone using a 24/7 interactive voice response system (IVRS), with back-up via the trial-specific web portal.

PATIENT MANAGEMENT

It will be recommended that the patient receives a minimum of 24 hours of their randomised strategy before strategy failure is deemed to have occurred. In patients randomised to standard therapy, MSD use, other than IABP, is discouraged. However, the physician in charge of the patient can allow “up-grading” of therapy (MSD in the standard care arm or additional MSD in the VA-ECMO arm) if, in their opinion, the patient would benefit. Such patients will be included in the intention-to-treat analysis but will be regarded as being in violation of the protocol, and so not included in the per-protocol analysis.

Group 1: standard therapy

Patients allocated to Group 1 will be managed as per standard practice, including inotropic or vasopressor support according to local practice/ESC guidelines18. IABP support will be permitted in this group since, based on IABP-SHOCK II, it does not benefit CGS patients19.

Group 2: immediate VA-ECMO support

In addition to standard care as per Group 1, patients in Group 2 will have peripheral VA-ECMO initiated from 30 minutes after completed P-PCI. VA-ECMO will be deployed as soon as possible and no later than six hours after randomisation, and within 24 hours of CGS diagnosis.

Peripheral VA-ECMO will be as per local practice. All included centres are experienced in VA-ECMO. Methods of left ventricle (LV) unloading, distal limb perfusion, maintenance of ejection/aortic valve opening and anticoagulation will be instituted as per sites’ usual care and consistent with VA-ECMO management standards.

Both randomised groups

Accepted and standard contemporary intensive care practices, including mechanical ventilation, will be as required. ECMO weaning in Group 2 will be in accordance with local practice and the patient’s clinical status. The aim will be to wean patients from the allocated treatment within seven days. Bridge to further strategies will be in accordance with the patient’s clinical condition and the routine practice in that department. In all patients, continuation of post-MI secondary prevention medication will be commenced and according to evidence-based international guidelines.

If a patient recovers from CGS after the PCI but subsequently deteriorates on the intensive care unit (ICU), they can still be considered for the trial but must be randomised within 24 hours of first diagnosis of CGS and be able to receive ECMO, if so randomised, within six hours.

PATIENT FOLLOW-UP

Patients will be followed up after discharge at 30 days (clinic visit), at 6 months (telephone) and at 12 months (clinic visit). Clinical status and admission and post-discharge procedural data will be collected.

STATISTICAL METHODS

The primary analyses will be based on an “intention-to-treat” basis. The primary analysis set will include all patients randomised. A two-sided significance level of 0.05 will be applied. Descriptive statistics for baseline characteristics will be presented by treatment group. The primary endpoint will be compared between groups using a log-rank test, stratified for the presence or absence of OHCA. Patients without an event will be censored at their last follow-up date or 30 days, whichever occurs first. The first two key secondary endpoints will be analysed similarly. For the third key secondary endpoint, mortality will be taken into account as a competing risk. To control the type-1 error, a hierarchical testing strategy will be applied for the key secondary endpoints. Interim analyses for safety are planned, with specific criteria determined by agreement with the data safety monitoring board (DSMB). The trial will not be stopped for futility and there will be no interim analysis for superiority. The DSMB and trial steering committee will monitor the study for feasibility and event rates.

A “per-protocol sub-analysis” will also be undertaken to compare those patients receiving ECMO within six hours and no further MSD (other than IABP to allow LV venting) before hospital discharge (in the intervention group) versus those who did not receive any MSD before hospital discharge (control group).

HEALTH ECONOMIC/COST-EFFECTIVENESS STUDY

We will undertake a robust analysis of costs, outcomes, cost-effectiveness and cost-utility of VA-ECMO compared to the control group. The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) will evaluate cost-efficacy. The impact of early VA-ECMO on quality of life and symptoms following recovery from CGS will be measured using the EQ5D (discharge, 30 days, and 6 and 12 months) and Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire (discharge and 30 days).

TRIAL SUBSTUDIES

There are two embedded substudies in EURO SHOCK:

– Cardiac magnetic resonance using novel shortened non-breath-holding protocols to evaluate infarct size, microvascular obstruction, myocardial haemorrhage, LV systolic function, LV volume (n=180).

– Impact of VA-ECMO membrane lining on platelet function (n=100).

ORGANISATION OF THE EURO SHOCK TRIAL

Thirty-nine centres throughout Europe will recruit to EURO SHOCK (Supplementary Appendix 3). Trial committees and sponsor are outlined in Supplementary Appendix 4.

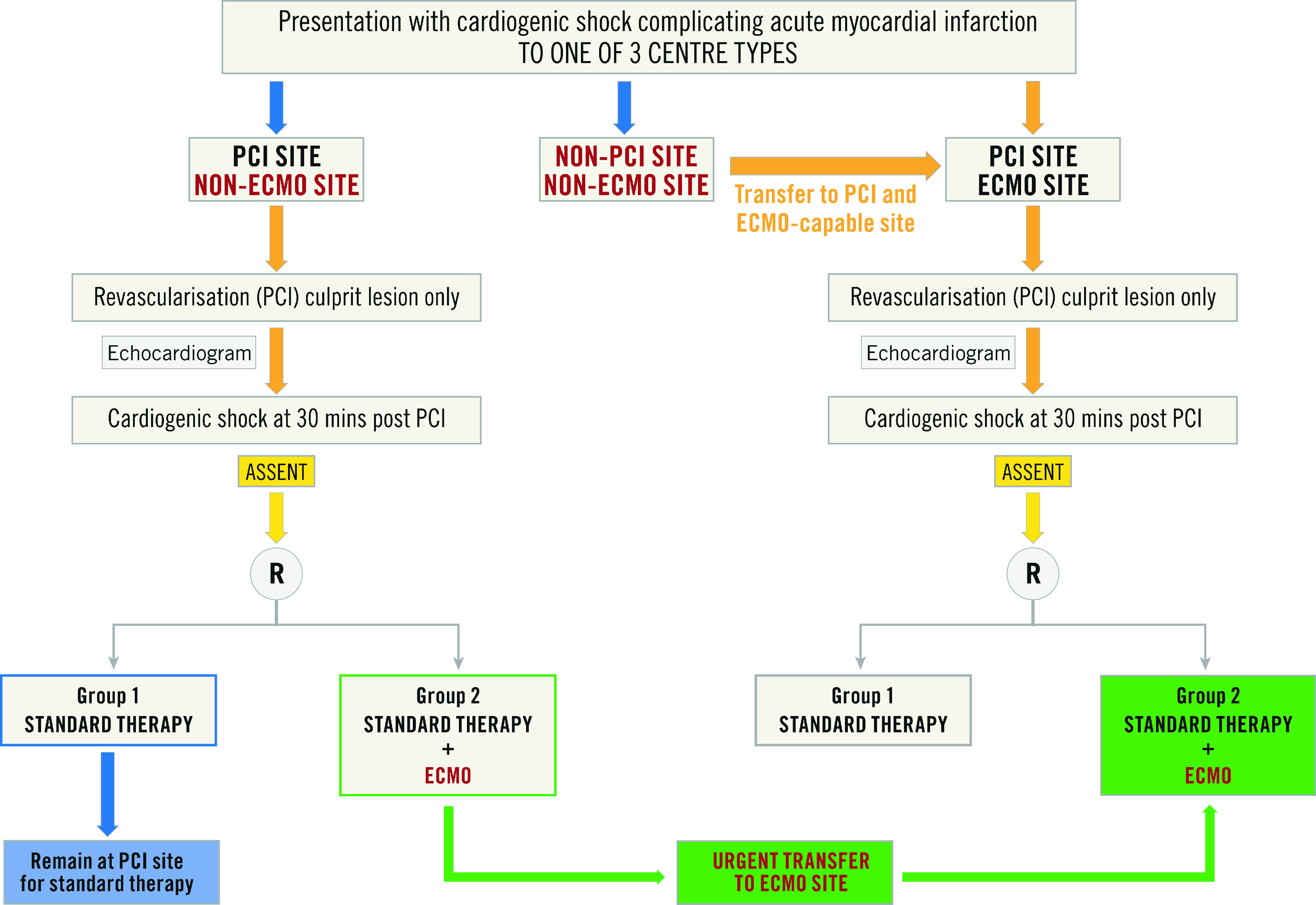

TRANSFER SYSTEMS AND EVALUATION OF TIMINGS FOR TRANSFER TO ECMO-CAPABLE CENTRES

Patients in CGS admitted to a non-ECMO centre, who fulfil EURO SHOCK criteria, will be randomised on site. Those randomised to the VA-ECMO arm will immediately be referred to the ECMO centre. Those randomised to the control arm will receive standard treatment at the site of randomisation. Transfer times and delays (between hub and spokes) will be documented. Figure 3 summarises the transfer of patients based on the type of site that the patient presents to with CGS.

Figure 3.

Patient flow diagram based on type of presenting centre.

RECRUITMENT TO THE EURO SHOCK TRIAL

Recruitment for the trial commenced in September 2019. The trial was suspended for the COVID pandemic from March 2020 until the end of June 2020, although not all centres reopened at this time. As of October 2020, 10 patients have been recruited (Spain n=3, Norway n=1, Germany n=4, UK n=2).

A total of 55 patients have been screened for the trial. The reasons for exclusion are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1. Reasons for screened patients being excluded from the trial.

| Main reason patient not included in the trial | N (%) |

| CGS did not occur within 24 hours of ACS event | 7 (13%) |

| Shock not due to ACS rather secondary to another cause (e.g., sepsis, anaphylaxis, myocarditis) | 3 (5%) |

| PCI was not attempted | 3 (5%) |

| CGS had resolved at 30 mins post PCI | 12 (22%) |

| Mechanical cause for CGS identified (e.g., VSD, ischaemic MR) | 9 (16%) |

| Frailty based on Canadian frailty score | 2 (4%) |

| Dementia | 1 (2%) |

| Severe peripheral vascular disease | 2 (4%) |

| Severe allergy or intolerance | 1 (2%) |

| OHCA: no ROSC/pH <7.0/no bystander CPR within 10 mins of collapse | 8 (15%) |

| Lactate <2.0 mmol/L | 1 (2%) |

| Other | 6 (11%) |

| ACS: acute coronary syndrome; CGS: cardiogenic shock; MR: mitral regurgitation; OHCA: out-of-hospital cardiac arrest; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; ROSC: return of spontaneous circulation; VSD: ventricular septal defect | |

The most common reason for trial exclusion was improvement in the clinical status of patients at 30 minutes post revascularisation, such that they were no longer (by definition) in CGS, emphasising the importance of early revascularisation in avoiding unnecessary use of MSD in this population.

The EURO SHOCK trial has continued to recruit patients while the centres have been open. With an increasing number of sites opening, the projected recruitment rate will increase. We anticipate completion of recruitment within 36 months.

Impact on daily practice

Should EURO SHOCK demonstrate that VA-ECMO reduces mortality from ACS CGS, it will lead to guideline recommendations, and proposals for the early transfer of CGS patients to ECMO-capable centres within “Shock Networks”.

Discussion

In the contemporary era, there has been little decline in mortality beyond that due to revascularisation10. A major reason for this is that, despite restoration of myocardial perfusion with PCI, myocardial dysfunction occurs, leading to insufficient cardiac output, with activation of compensatory mechanisms that result in peripheral vasoconstriction, further reduction in peripheral and coronary perfusion, and perpetuation of myocardial ischaemia20. Addressing poor cardiac output and maintaining haemodynamic response as optimally and as early as possible could be important in attenuating the “spiral of decline”. Mechanical support devices provide haemodynamic support and offer possible solutions. IABP has shown no benefit in CGS19. The Impella device has shown limited benefit in small retrospective studies21,22, possibly due to flow rates with older iterations, or due to timing use. The Impella is currently under evaluation in the DanGer Shock study (NCT01633502).

VA-ECMO allows maintenance of cardiac output to support peripheral organ flow while the heart recovers. However, VA-ECMO is not without potential complications and its cost demands comparative cost-effectiveness analysis. There are conflicting data on the efficacy of VA-ECMO in CGS, with some retrospective studies suggesting a lack of benefit23,24. However, a key factor in retrospective studies was the timing of VA-ECMO. Since most were deployed late in the course of CGS, VA-ECMO was less likely to show benefit.

EURO SHOCK is one of five trials currently recruiting comparing the use of MSD with standard therapy in CGS complicating AMI (Table 2). While the inclusion criteria are similar among the trials, when looking specifically at the ECMO trials, a key difference between EURO SHOCK and ECLS-SHOCK is the timing of ECMO implementation. As shown above from the screening data, over 20% of patients who were screened for EURO SHOCK were excluded due to improvement in CGS following PCI – as explained above, the design of EURO SHOCK considers revascularisation first as an important point as this could prevent the use of ECMO with its associated costs and complications in patients who may not require it, while still ensuring that ECMO is commenced early enough to prevent development of refractory shock and multi-organ failure. Both the ANCHOR and ECMO-CS trials include the need for rescue ECMO as part of the primary endpoint, whereas this is a secondary endpoint in EURO SHOCK.

Table 2. Current major trials assessing use of MSD in cardiogenic shock complicating acute myocardial infarction.

| Study | N | Randomisation groups | Primary outcome |

| EURO SHOCK (NCT03813134) | 428 | Patients presenting with CGS complicating acute MI, randomised to either immediate VA-ECMO or standard therapy if persistent CGS 30 mins following revascularisation with PCI. VA-ECMO commenced as soon as possible and no later than 6 hours after randomisation. | Mortality at 30 days. |

| ECMO-CS (NCT02301819) | 120 | Patients with rapidly deteriorating or severe cardiogenic shock, randomised to either immediate VA-ECMO or early conservative therapy (including PCI/cardiac surgery). | Composite: all-cause mortality, resuscitated circulatory arrest and implantation of another MSD at 30 days. |

| ANCHOR (NCT04184635) | 400 | Patients presenting with CGS complicating acute MI, randomised to standard therapy including revascularisation, vs standard therapy with VA-ECMO implantation started as soon as possible (commenced in non-ECMO centre by mobile ECMO team prior to patient transfer to ECMO centre). | Treatment failure at 30 days (death in ECMO group, death or rescue ECMO in the control group). |

| ECLS-SHOCK (NCT03637205) | 420 | Patients presenting with CGS complicating acute MI, randomised to standard therapy including revascularisation vs standard therapy with VA-ECMO implantation prior to revascularisation. | Mortality at 30 days. |

| DanGer Shock (NCT01633502) | 360 | Patients with AMI-CS randomised to standard therapy or Impella CP implanted prior to revascularisation. | Mortality at 180 days. |

| AMI-CS: acute myocardial infarction - cardiogenic shock; CGS: cardiogenic shock; ECMO: extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; MI: myocardial infarction; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; VA-ECMO: veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation | |||

All mechanical support devices have their drawbacks and complications25,26,27. In the case of ECMO, these mostly relate to left ventricular offloading and access-site complications. All centres are ECMO experienced and deal with such issues on a regular basis. We are asking them to perform standard ECMO, which may include the use of IABP for offloading the ventricle. All ECMO complications are listed as serious adverse events (SAE) and will be adjudicated by the independent clinical events committee (CEC) which will prepare these for the DSMB which can request clarification on ECMO complications through our ECMO advisory board headed by Prof. Alain Vuylsteke. Indeed, one important objective in EURO SHOCK is to determine the clinical risk/benefit as well as the cost/benefit of ECMO used in the strategy tested in this trial.

Limitations

The trial will only evaluate one device, VA-ECMO, and we have been speculative, albeit conservative, in our power calculations, based on the available literature. The trial will be open-label, which could lead to systematic bias; however, independent adjudication and blinding of endpoint evaluation will mitigate the effects of this.

Conclusions

EURO SHOCK is a strategy trial to answer robustly in a sufficiently powered randomised clinical trial whether early intention to treat with VA-ECMO after acute PCI attenuates multi-organ failure, reducing mortality and morbidity in CGS.

The trial is directed by a consortium of experienced clinical academics and will be run to the highest research governance principles.

Appendix. Study collaborators

Jay Gracey, BA (Hons), Mel Ferguson, BA (Hons), Hakeem Yusuff, MBBS, FFICM, Cat Taylor, BSc, MSc, PhD; University of Leicester, University Hospitals of Leicester, Leicester Biomedical Research Centre, Leicester, United Kingdom. Jeanette Mueller, MSc, PhD; Accelopment AG, Zurich, Switzerland. Philip Bousfield, BSc; Chalice Medical, Worksop, United Kingdom.

Supplementary data

Primary and secondary endpoints of EURO SHOCK.

Substudies.

Lead principal investigators and recruiting centres for the EURO SHOCK study.

Trial committees.

Review of studies reporting mortality from cardiogenic shock.

Work package summary.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The EURO SHOCK trial has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme - grant agreement No. 754946.

Conflict of interest statement

The following authors disclose grants from the European Union Horizons 2020 programme for the EURO SHOCK study: T. Adriaenssens, C. Berry, K. Bogaerts, A.K. Erglis, G. Guagliumi, S. Haine, A. Kastrati, T. Myrmel, S. Massberg, M. Flather, M. Sabaté, C. Vrints and A. Gershlick. M. Sabate reports personal fees from Abbott Vascular and iVascular. M. Orban reports personal fees from AstraZeneca, Abiomed, Bayer Vital, Cytosorbents, and Sedana Medical, outside the submitted work. C. Berry reports grants and other from Abbott Vascular and AstraZeneca, non-financial support and other from Coroventis, grants and other from GSK, Novartis, other from Neovasc, Medyria, and Siemens Healthcare, and grants and other from HeartFlow, outside the submitted work. G. Guagliumi reports grants and personal fees from Abbott Vascular, personal fees from Boston Scientific, and grants and personal fees from Infraredx, outside the submitted work. P. Bousfield (the managing director of Chalice Medical) is a supplier of equipment used for ECMO in the UK and Europe and as such has commercial interests. Their involvement in the EURO SHOCK trial is such that the use of their equipment is not actively promoted because centres are encouraged to use whatever ECMO devices they are familiar with and use under their current practice. The other authors/study collaborators have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Abbreviations

- ACE

angiotensin-converting enzyme

- ACS

acute coronary syndrome

- ARB

angiotensin receptor blocker

- BARC

Bleeding Academic Research Consortium

- BCIS

British Cardiovascular Intervention Society

- CABG

coronary artery bypass grafting

- CGS

cardiogenic shock

- CHF

chronic heart failure

- CI

confidence interval

- CMR

cardiac magnetic resonance

- CRT

cardiac resynchronisation therapy

- CVD

cardiovascular disease

- DSMB

data safety monitoring board

- ECG

electrocardiogram

- ECMO

extracorporeal membrane oxygenation

- eCRF

electronic case report form

- EU

European Union

- IABP

intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation pump

- ICD

implantable cardioverter-defibrillator

- ICER

incremental cost-effectiveness ratio

- IVRS

interactive voice response system

- LV

left ventricle

- m-MDT

mini-multidisciplinary team

- MACE

major adverse cardiovascular events

- MI

myocardial infarction

- MSD

mechanical support device

- N-STEMI

non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction

- OHCA

out-of-hospital cardiac arrest

- P-PCI

primary percutaneous coronary intervention

- PCI

percutaneous coronary intervention

- SBP

systolic blood pressure

- STEMI

ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction

- TSC

trial steering committee

- VA-ECMO

veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation

- VARC

Valve Academic Research Consortium

Contributor Information

Amerjeet Banning, University of Leicester, University Hospitals of Leicester, Leicester Biomedical Research Centre, Leicester, United Kingdom.

Tom Adriaenssens, University Hospitals Leuven, and Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Department of Cardiovascular Sciences, Leuven, Belgium.

Colin Berry, University of Glasgow, Institute of Cardiovascular and Medical Sciences and Robertson Centre for Biostatistics, Glasgow, United Kingdom.

Kris Bogaerts, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Department of Public Health and Primary Care, I-BioStat, and Universiteit Hasselt, I-BioStat, Leuven, Belgium.

Andrejs Erglis, Paula Stradina Kliniska Universitates Slimnica AS, Department of Cardiovascular Sciences, Riga, Latvia.

Klaus Distelmaier, Medical University of Vienna, Department of Internal Medicine II, Division of Cardiology, Vienna, Austria.

Giulio Guagliumi, Azienda Ospedaliera Papa Giovanni XXIII, Department of Cardiovascular Sciences, Bergamo, Italy.

Steven Haine, Antwerp University Hospital, Department of Cardiology and University of Antwerp, Department of Cardiovascular Diseases, Antwerp, Belgium.

Adnan Kastrati, Deutsches Herzzentrum München, Department of Cardiology, Munich, Germany.

Steffen Massberg, Medizinische Klinik und Poliklinik I, LMU University Hospital Munich, Munich, Germany.

Martin Orban, Medizinische Klinik und Poliklinik I, LMU University Hospital Munich, Munich, Germany.

Truls Myrmel, The Heart and Lung Clinic, University Hospital North Norway, Tromsø, Norway.

Alain Vuylsteke, Royal Papworth Hospital, Department of Anaesthesia and Intensive Care, Cambridge, United Kingdom.

Fernando Alfonso, Cardiac Department, La Princesa University Hospital, IIS-IP, CIBERCV, Madrid, Spain.

Frans Van de Werf, University Hospitals Leuven, and Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Department of Cardiovascular Sciences, Leuven, Belgium.

Freek Verheugt, Heartcenter, Onze Lieve Vrouwe Gasthuis (OLVG), Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

Marcus Flather, University of East Anglia and Norfolk and Norwich University Hospital, Norwich, United Kingdom.

Manel Sabaté, Consorci Institut D’Investicacions Biomediques August Pi i Sunyer, Cardiovascular Institute, Hospital Clínic, Barcelona, Spain.

Christiaan Vrints, Antwerp University Hospital, Department of Cardiology and University of Antwerp, Department of Cardiovascular Diseases, Antwerp, Belgium.

Anthony Gershlick, University of Leicester, University Hospitals of Leicester, Leicester Biomedical Research Centre, Leicester, United Kingdom.

References

- Kolte D, Khera S, Aronow WS, Mujib M, Palaniswamy C, Sule S, Jain D, Gotsis W, Ahmed A, Frishman WH, Fonarow GC. Trends in incidence, management, and outcomes of cardiogenic shock complicating ST-elevation myocardial infarction in the United States. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3:e000590. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.113.000590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludman PF on behalf of the British Cardiovascular Intervention Society. BCIS Audit Returns: Adult Interventional Procedures. Jan 2016 to Dec 2016. http://www.bcis.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/BCIS-Audit-2016-data-ALL-excluding-TAVI-08-03-2018-for-web.pdf.

- Kunadian V, Qiu W, Ludman P, Redwood S, Curzen N, Stables R, Gunn J, Gershlick A National Institute for Cardiovascular Outcomes Research. Outcomes in patients with cardiogenic shock following percutaneous coronary intervention in the contemporary era: an analysis from the BCIS database (British Cardiovascular Intervention Society). JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2014;7:1374–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2014.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Diepen S, Katz JN, Albert NM, Henry TD, Jacobs AK, Kapur NK, Kilic A, Menon V, Ohman EM, Sweitzer NK, Thiele H, Washam JB, Cohen MG American Heart Association Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research; Mission: Lifeline. Contemporary management of cardiogenic shock: a Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017;136:e232–e68. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah RU, de Lemos JA, Wang TY, Chen AY, Thomas L, Sutton NR, Fang JC, Scirica BM, Henry TD, Granger CB. Post-Hospital Outcomes of Patients With Acute Myocardial Infarction With Cardiogenic Shock: Findings From the NCDR. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67:739–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.11.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeger RV, Assmann SF, Yehudai L, Ramanathan K, Farkouh ME, Hochman JS. Causes of death and re-hospitalization in cardiogenic shock. Acute Card Care. 2007;9:25–33. doi: 10.1080/17482940601178039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambrosetti M, Griffo R, Tramarin R, Fattirolli F, Temporelli PL, Faggiano P, De Feo S, Vestri AR, Giallauria F, Greco C. Prevalence and 1-year prognosis of transient heart failure following coronary revascularization. Intern Emerg Med. 2014;9:641–7. doi: 10.1007/s11739-013-1006-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunadian V, Qiu W, Bawamia B, Veerasamy M, Jamieson S, Zaman A. Gender comparisons in cardiogenic shock during ST elevation myocardial infarction treated by primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Am J Cardiol. 2013;112:636–41. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2013.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiele H, Ohman EM, Desch S, Eitel I, de Waha S. Management of cardiogenic shock. Eur Heart J. 2015;36:1223–30. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochman JS, Sleeper LA, Webb JG, Sanborn TA, White HD, Talley JD, Buller CE, Jacobs AK, Slater JN, Col J, McKinlay SM, LeJemtel TH. Early revascularization in acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock. SHOCK Investigators. Should We Emergently Revascularize Occluded Coronaries for Cardiogenic Shock. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:625–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199908263410901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeymer U, Bueno H, Granger CB, Hochman J, Huber K, Lettino M, Price S, Schiele F, Tubaro M, Vranckx P, Zahger D, Thiele H. Acute Cardiovascular Care Association position statement for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock: A document of the Acute Cardiovascular Care Association of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2020;9:183–97. doi: 10.1177/2048872619894254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pöss J, Köster J, Fuernau G, Eitel I, de Waha S, Ouarrak T, Lassus J, Harjola VP, Zeymer U, Thiele H, Desch S. Risk Stratification for Patients in Cardiogenic Shock After Acute Myocardial Infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69:1913–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsao NW, Shih CM, Yeh JS, Kao YT, Hsieh MH, Ou KL, Chen JW, Shyu KG, Weng ZC, Chang NC, Lin FY, Huang CY. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation-assisted primary percutaneous coronary intervention may improve survival of patients with acute myocardial infarction complicated by profound cardiogenic shock. J Crit Care. 2012;27:530.e1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2012.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheu JJ, Tsai TH, Lee FY, Fang HY, Sun CK, Leu S, Yang CH, Chen SM, Hang CL, Hsieh YK, Chen CJ, Wu CJ, Yip HK. Early extracorporeal membrane oxygenator-assisted primary percutaneous coronary intervention improved 30-day clinical outcomes in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction complicated with profound cardiogenic shock. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:1810–7. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181e8acf7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouweneel DM, Schotborgh JV, Limpens J, Sjauw KD, Engstrom AE, Lagrand WK, Cherpanath TGV, Driessen AHG, de Mol B, Henriques JPS. Extracorporeal life support during cardiac arrest and cardiogenic shock: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2016;42:1922–34. doi: 10.1007/s00134-016-4536-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrage B, Dabboura S, Yan I, Hilal R, Neumann JT, Sorensen NA, Gossling A, Becher PM, Grahn H, Wagner T, Seiffert M, Kluge S, Reichenspurner H, Blankenberg S, Westermann D. Application of the SCAI classification in a cohort of patients with cardiogenic shock. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2020;96:E213–9. doi: 10.1002/ccd.28707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiele H, Ohman EM, de Waha-Thiele S, Zeymer U, Desch S. Management of cardiogenic shock complicating myocardial infarction: an update 2019. Eur Heart J. 2019;40:2671–83. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, Bueno H, Cleland JG, Coats AJ, Falk V, González-Juanatey JR, Harjola VP, Jankowska EA, Jessup M, Linde C, Nihoyannopoulos P, Parissis JT, Pieske B, Riley JP, Rosano GM, Ruilope LM, Ruschitzka F, Rutten FH, van der Meer P Authors/Task Force Members; Document Reviewers. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: The Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur J Heart Fail. 2016;18:891–975. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiele H, Zeymer U, Neumann FJ, Ferenc M, Olbrich HG, Hausleiter J, Richardt G, Hennersdorf M, Empen K, Fuernau G, Desch S, Eitel I, Hambrecht R, Fuhrmann J, Böhm M, Ebelt H, Schneider S, Schuler G, Werdan K IABP-SHOCK II Trial Investigators. Intraaortic balloon support for myocardial infarction with cardiogenic shock. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1287–96. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1208410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds HR, Hochman JS. Cardiogenic shock: current concepts and improving outcomes. Circulation. 2008;117:686–97. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.613596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill WW, Schreiber T, Wohns DH, Rihal C, Naidu SS, Civitello AB, Dixon SR, Massaro JM, Maini B, Ohman EM. The current use of Impella 2.5 in acute myocardial infarction complicated by cardiogenic shock: results from the USpella Registry. J Interv Cardiol. 2014;27:1–11. doi: 10.1111/joic.12080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouweneel DM, Eriksen E, Sjauw KD, van Dongen IM, Hirsch A, Packer EJS, Vis MM, Wykrzykowska JJ, Koch KT, Baan J, de Winter RJ, Piek JJ, Lagrand WK, Mol de Mol BA, Tijssen JG, Henriques JP. Percutaneous Mechanical Circulatory Support Versus Intra-Aortic Balloon Pump in Cardiogenic Shock After Acute Myocardial Infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69:278–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Waha S, Graf T, Desch S, Fuernau G, Eitel I, Pöss J, Jobs A, Stiermaier T, Ledwoch J, Wiedau A, Lurz P, Schuler G, Thiele H. Outcome of elderly undergoing extracorporeal life support in refractory cardiogenic shock. Clin Res Cardiol. 2017;106:379–85. doi: 10.1007/s00392-016-1068-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Waha S, Fuernau G, Desch S, Eitel I, Wiedau A, Lurz P, Schuler G, Thiele H. Long-term prognosis after extracorporeal life support in refractory cardiogenic shock: results from a real-world cohort. EuroIntervention. 2016;11:1363–71. doi: 10.4244/EIJV11I12A265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abaunza M, Kabbani LS, Nypaver T, Greenbaum A, Balraj P, Qureshi S, Alqarqaz MA, Shepard AD. Incidence and prognosis of vascular complications after percutaneous placement of left ventricular assist device. J Vasc Surg. 2015;62:417–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2015.03.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johannsen L, Mahabadi AA, Totzeck M, Krueger A, Jánosi RA, Rassaf T, Al-Rashid F. Access site complications following Impella-supported high-risk percutaneous coronary interventions. Sci Rep. 2019;9:17844. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-54277-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zangrillo A, Landoni G, Biondi-Zoccai G, Greco M, Greco T, Frati G, Patroniti N, Antonelli M, Pesenti A, Pappalardo F. A meta-analysis of complications and mortality of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Crit Care Resusc. 2013;15:172–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Primary and secondary endpoints of EURO SHOCK.

Substudies.

Lead principal investigators and recruiting centres for the EURO SHOCK study.

Trial committees.

Review of studies reporting mortality from cardiogenic shock.

Work package summary.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.