Abstract

Background:

As federal research funding focuses more on academic/community collaborations to address health inequities; it is important to understand characteristics of these partnerships and how they work to achieve health equity outcomes.

Objectives:

This study built on previous National Institutes of Health–funded research to: (a) describe partnership characteristics and processes of federally funded, community-based participatory research (CBPR) or community-engaged research (CEnR) projects; (b) explore characteristics of these projects by stage of funding; and (c) build on previous understanding of partnership promising practices.

Methods:

Between fall 2016 and spring 2017, we completed a cross-sectional analysis and principal component analysis of online survey data from key informants of federally funded CBPR and CEnR projects. Respondents for 179 projects (53% response rate) described project characteristics (e.g., type of partner, stage of partnership, and population) and the use of promising practices (e.g., stewardship, advisory board roles, training topics) by stage of partnership.

Results:

Projects involved community, healthcare, and government partners, with 49% of respondents reporting their project was in the early stage of funding. More projects focused on Black/African-American populations, while principal investigators were mostly White. The more established a partnership (e.g., with multiple projects), the more likely it employed the promising practices of stewardship (i.e., community safeguards for approval), community advisory boards, and training on values and power.

Conclusions:

Community engagement is a developmental process with differences between early-stage and established CBPR partnerships. Engaging in active reflection and adopting promising partnering practices are important for CBPR partnerships working to improve health equity. The data provided in this study provide key indicators for reflection.

Keywords: CBPR, community-based participatory research, community engagement

Community-based participatory research (CBPR) and other forms of community-engaged research (CEnR) are approaches that can promote equity between and among academic and community partners involved in research partnerships (Wallerstein, Duran, Oetzel, & Minkler, 2017). Both approaches seek mutual contribution of decision-making, priority setting, and resource sharing by all partners, with the core goal of addressing inequities in social and health outcomes faced by underserved populations and communities. The use of CBPR in research has grown as the priorities within the National Institutes of Health (NIH) have increased over the past decades (Leviton & Green, 2017). These approaches are increasingly seen as a strategy to increase the capacity of communities to address the NIH goal of translation, in which research results are applied to improve community programs, practices, or policies for better population health. Many of the challenges involved in the translation and dissemination of evidence-based practices, such as ensuring that interventions or research results resonate with community values and practices can be addressed by CBPR strategies that recognize the importance of context and external validity of research interventions (Wallerstein & Duran, 2010). The purpose of this paper is to connect the priorities of federal agencies to address health equity research with academic–community partnerships that use successful and promising CBPR engagement practices.

Many disciplines have used CBPR approaches in research, including sociology, public health, medicine, psychology, political science, and education. In particular, nursing science has an expansive history in research that considers the importance of community engagement—especially, CBPR—to improve health outcomes, decrease health disparities, and test evidence-based interventions (Grady & McIlvane, 2016). This is exhibited by the historical support from the National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR, 2010) which has funded CBPR-focused projects since 1996.

The nursing research literature demonstrates a growing emphasis on CBPR practices. Nursing publications evaluating CBPR include reviews on CBPR research and tool development (Kelly, 2005; Portillo & Waters, 2004); recommendations on how to use CBPR among various communities and populations (Anderson et al., 2014; Averill, 2008; Shattell, 2014); and various nursing education models for teaching CBPR to nursing students (Csiernik, O’Regan, Forchuk, & Rudnick, 2018; Zandee et al., 2015). Both quantitative and qualitative data-intensive studies deploying CBPR and CEnR have evaluated dynamics related to midwifery and maternity care (Foster et al., 2015; Furman, Matthews, Davis, Killpack, & O’Riordan, 2016), cancer screening (Nguyen-Truong et al., 2018), geriatric nursing (Petersson & Blomqvist, 2011), public health and communicable disease (Cusack, Cohen, Mignoen, Chartier, & Lutfiyya, 2018; Ismail, Gerrish, Salway, & Chowbey, 2014), and youth suicide/substance abuse in Native-American communities (Holliday, Wynne, Katz, Ford, & Barbosa-Leiker, 2018).

The current investigation derived from a previous NIH-funded, pilot study (2006–2009) that produced a CBPR conceptual model (Kastelic, Wallerstein, Duran, & Oetzel, 2017). This CBPR conceptual model was created to identify pathways of partnering that could lead to specific outcomes and identify barriers and facilitators of effective partnerships. Based on Freire’s (1970) pedagogy, the CBPR conceptual model incorporates a framework of collective reflection, evaluation, and action to strengthen the quality of how academic/community partnerships work together to reach their desired outcomes. The model consists of four domains (context, partnership processes, intervention and research, and outcomes) which hypothesize that the context of individuals forming a partnership creates foundational processes within which partners work together. These processes shape the design of the intervention and research which translates to the intermediate outcomes (such as empowerment, individual/agency capacity, sustainability of projects) and long-term outcomes (policies, improved health, and health equity) of the work performed together (Wallerstein et al., 2008).

The pilot study was followed by Research for Improved Health (RIH; 2009–2013), an NIH-funded R01 study that used mixed-methods analysis to test and validate psychometric properties of measures within the CBPR model and to ascertain how the domains related to one another (Oetzel et al., 2018; Oetzel, Zhou et al., 2015). The mixed-methods design was based on a two-stage survey of 294 federally funded community/academic partnerships, with eight, in-depth case studies nationwide (Lucero et al., 2018; Pearson et al., 2015). Principal investigators (PIs) or designates were first surveyed, followed by surveys of four nominated partners about partnership structures and partnerships. The findings demonstrated greater variability in the nature of partnerships around partnership agreements, funding sources, resource sharing, and project outcomes, particularly identifying differences in projects that involve American-Indian or Alaska-Native populations compared with other ethnic groups (Oetzel, Villegas et al., 2015; Pearson et al., 2015). Furthermore, the results provided a multiple logistic regression analysis and a structural equation model of the CBPR model domain constructs, identifying initial promising engagement practices and processes (e.g., community stewardship, training and discussion on power/values) that were associated with community transformation and health outcomes and national benchmarks (Oetzel et al., 2018).

In 2015, the NINR awarded an R01 for the current project, Engage for Equity: Advancing Community Engaged Partnerships (E2), to validate and strengthen measures and tools used in CBPR/CEnR, and to further evaluate how promising practices of partnerships can improve research outcomes. The project is itself a transdisciplinary partnership involving the University of New Mexico’s Center for Participatory Research, the University of Washington, the Community-Campus Partnerships for Health, the National Indian Child Welfare Association, the University of Waikato New Zealand, the Rand Corporation, and a Think Tank comprised community and academic CBPR practitioners. E2 sought to extend the science of CBPR and CEnR by developing metrics and tools to strengthen partnering and engagement processes. The aims of this study were to refine, deepen, and strengthen CBPR/CEnR measures and practices identified in prior research by surveying a more recent sample of partnership members (PIs with their community and academic partners) from federally funded research projects about their partnership and practice of community engagement, and to conduct a randomized control trial comparing the effectiveness of two interventions to deliver CBPR tools to strengthen partnership practices.

Although a growing number of CBPR/CEnR studies have documented the application of some similar promising practices for partnership (Jagosh et al., 2015; Khodyakov et al., 2011; Wallerstein et al., 2017), additional research is needed to further understand how the practices work and how partners are working together. For example, the practices of approval for research participation, written agreements, and shared control of resources by community partners previously served as a proxy for the promising practice of shared power and stewardship of community interests (Oetzel, Villegas et al., 2015, Pearson et al., 2015). This previous research established the presence of these practices, leaving room to consider if such practices are perceived to help steward the research project, provide oversight to ensure equitable research ethics, help integrate local knowledge, and benefit the community. Furthermore, advisory groups have been accepted as important strategies for community involvement in decision-making (Eder et al., 2018; Wilkins et al., 2013), yet there is a need to understand how many projects use these groups and the roles they play. Finally, much of the CBPR literature identifies whether partnerships are at a particular stage (i.e., new partnership vs. long-term partnership) (Duran et al., 2013); however, most do not discuss differences based on their stages (Wallerstein et al., 2017; Wallerstein et al., 2008) and it has not been examined empirically. Therefore, we sought to explore whether there are differences in structures and practices among partnerships within different stages of funding, such as early planning stage or pilot funding, ongoing partnership with an existing single project, and established partnership with multiple projects.

As nursing scientists increasingly engage communities in evidence-based intervention research and the translation to evidence-based practice, it is critical to understand how academic/community partnerships can best work together to achieve desired outcomes for patient populations and communities. Having a clear understanding of the essential characteristics of partnerships that contribute to successful outcomes is important for nursing and other health researchers interested in supporting community partners to identify and address health inequities in their communities. This article details the sampling of 179 federally funded community/academic research partnerships and reviews how key informants (mostly PIs) describe the characteristics of the partnerships, including the use of partnership processes by the stage, or phase, of the partnership funding (early, single project, and multiple project). These data will build on previous key informant perspectives regarding their partnerships (Pearson et al., 2015) and deepen our understanding of what federally funded, community/academic CBPR/CEnR research partnerships look like, and how closely related their use of promising partnership practices is with the stage of their partnership.

Methods

Baseline data for E2 was collected in a three-stage, cross-sectional format and involved the use of two survey tools previously used in the RIH study. The first data collection stage involved identifying the sample of CBPR/CEnR projects with federal funding. The second stage included inviting PIs of the projects to complete the key informant survey (KIS). PIs also identified up to four partners (including at least one academic partner) to join them in completing a second, community-engaged survey (CES). In the third stage, the PIs and their nominated partners completed the CES. The current study focused on the first two stages of data. This study protocol was approved by a university’s institutional review board, #16–098.

Sampling Frame

We replicated and built on the sampling strategy from the previous RIH project (Lucero et al., 2018; Oetzel, Zhou et al., 2015; Pearson et al., 2015), with several additional modifications. First, we employed a two-stage, sampling design for PIs of federally funded, community/academic partnership projects. The first stage identified more established, longer-term CEnR projects from NIH RePORTER for all federally funded projects in 2015. Second, to capture projects that require community–stakeholder engagement and that are more likely to collaborate with diverse target populations, we included the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)-funded Prevention Research Centers (PRCs), the Native American Research Centers for Health (NARCH) projects funded by multiple NIH Institutes, and funded projects from the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI). Third, we specifically included projects funded under announcements PAR-11–346 (https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/pa-files/PAR-11-346.html) and RFA-DA-10–009 (https://grants.nih.gov/grants/guide/rfa-files/RFA-DA-10-009.html) because these were required to have strong community engagement processes. Finally, we slightly modified the Python 3.5 keyword search algorithm to apply to the NIH ExPORTER database to expand the diversity of community engagement and to include projects that partner with Spanish-speaking communities. We expanded to a few Spanish-language keywords because it is the second most common language in the United States, and because it provided an opportunity to be more inclusive of CPBR partnership and test the instruments in another language.

Sampling was conducted between September 2015 and May 2016 from four online repositories: NIH ExPORTER/RePORTER (http://exporter.nih.gov/), PCORI Portfolio of Funded Projects (https://www.pcori.org/), PRC project database (http://www.cdc.gov/prc/), and NARCH directories (https://www.nigms.nih.gov/Research/CRCB/NARCH/Pages/default.aspx). The databases included project-level administrative and financial information, such as PI and grantee organization contact information, target population, funding amount and duration, funding mechanism, project type, abstracts, and summaries. The sampling inclusion criteria were that the research project must have: (a) involved human participants; (b) been active in March 2015; (c) been funded through June 2018 or beyond; (d) used community partnership, CBPR, or significant CEnR approaches; and (e) been performed in the U.S. The projects that did not meet the criteria were excluded from the sample.

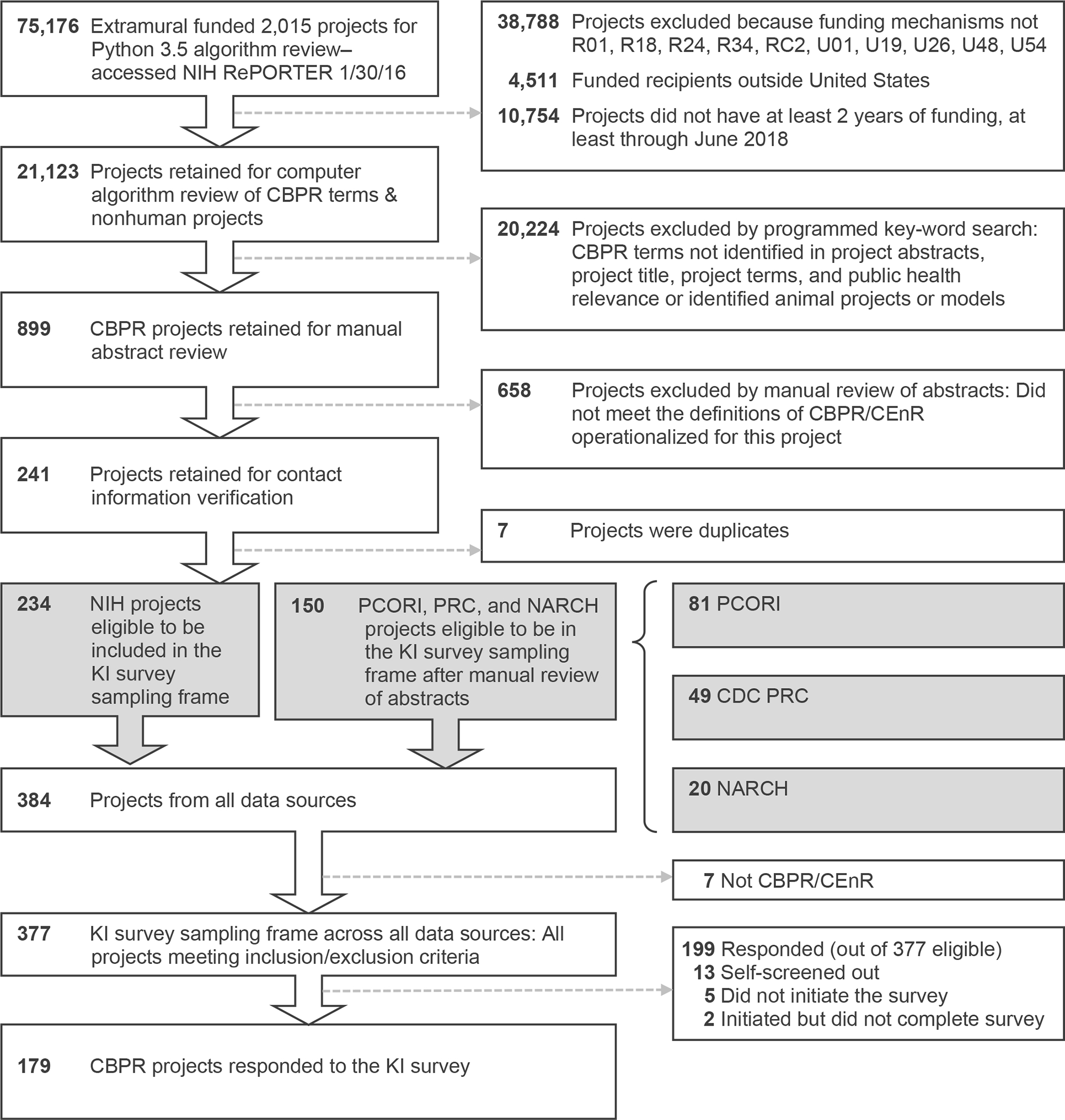

After retrieving all project-level information for 75,176 projects funded in the 2015 calendar year from the NIH ExPORTER database, we applied a series of keyword search and filtering algorithms to project abstracts, developed in Python 3.5 programming (Figure 1). We retained all projects that were funded through R and U mechanisms (R01, R18, R24, R34, RC1, RC2, U01, U10, U26, U48, and U54) and then applied a word filter to retain projects that contained any of the following terms independently: action research, bidirectional, cbpr, cenr, chw, collaborative partner, community health representative, community health worker, community-based, community-driven, community-engag, ctn, ctp, iterative process, lay health worker, narch, patient engag, pcor, prevention research center, promotora, promotores, research partner, service providers, stakeholder engag, stakeholder-engag, tribal, tribe, PAR-11–346, RFA-DA-10–009.

FIGURE 1.

Process to identify federally funded projects for sample.

CBPR = community-based participatory research; CDC = Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; CEnR = community-engaged research; KI = key informant; NARCH = Native American Research Centers for Health projects; NIH = National Institutes of health; PCORI = Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute; PRC = Prevention Research Center projects.

Using the algorithm, we identified 899 potential CBPR/CEnR projects. To assess specificity and sensitivity of our key-term algorithms, four team members then manually reviewed a random sample of 100 project-level abstracts from each database to ascertain whether a project met inclusion/exclusion criteria. We applied the same abstract review protocol to PCORI, PRC, and NARCH projects. This resulted in a final baseline survey sample of 384 community-academic partnerships projects, federally funded in year 2015, with 234 from NIH ExPORTER, 81 from PCORI, 49 from CDC PRC, and 20 from NARCH. Figure 1 provides a visual representation of the filtering process deployed to identify the projects comprising our sample.

Survey Tools and Measures

The E2 study used two separate instruments: (a) the KIS for PIs; and (b) the CES for PIs and their identified community and academic partners. The KIS included questions capturing the key “factual” information about the project and partnership that could be identified by a PI or designate. The CES sought to identify perceptual information about partnership structures, processes, and outcomes. The previous RIH study included measures we labeled as promising practices: formal agreements, budget sharing, approvals of the project on behalf of the community, and types of training offered (Pearson et al., 2015). The descriptive items and evaluation measures from RIH included: (a) funding sources; (b) primary study type (pilot, descriptive, intervention, policy, dissemination and implementation, other); (c) development of new evaluation measures (yes/no); (d) length of project and partnership; (e) who initiated the project (community partner, academic partner, both); (f) PI gender and group membership; (g) populations served (various identity, health, and social groups); and (h) project outcomes.

In the E2 study, we built from the earlier RIH study to refine some measures and include others. We first incorporated the RIH descriptive items previously mentioned and added the following new ones: (a) an expanded list of community partners (healthcare, governmental, or community; Table 1); (b) whether the study was a multilevel intervention (yes/no); and most importantly, for our analysis, (c) stage of partnership (early, single project, and multiple project).

TABLE 1.

Project Features and Partnership Characteristics (n = 179)

| Characteristic | n | % |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Project initiation | ||

| Community partners | 6 | 3 |

| Academic partners | 84 | 47 |

| Both | 87 | 49 |

| Other | 2 | 1 |

| Types of community partners (not mutually exclusive) | ||

| Patients or caregivers | 86 | 48 |

| Health care (staff, providers, clinics, systems) | 135 | 75 |

| Community (individuals, associations, organizations) | 153 | 86 |

| Government (local, state, federal, tribal agencies) | 89 | 50 |

| Policy makers | 45 | 25 |

| Nationally based membership associations | 21 | 12 |

| Other community partners | 52 | 29 |

| Stage of partnership by funding type | ||

| Early stage (planning grant/pilot or new collaboration) | 86 | 49 |

| Single-project partnership | 42 | 24 |

| Multiple-project partnership | 48 | 27 |

| Primary study type | ||

| Pilot | 8 | 5 |

| Descriptive | 12 | 7 |

| Intervention | 106 | 59 |

| Policy | 5 | 3 |

| Dissemination and implementation | 22 | 12 |

| Some other type | 26 | 15 |

| Multilevel intervention study | ||

| Yes | 56 | 54 |

| No | 48 | 46 |

| Community advisory board separate from partnership | ||

| Yes | 94 | 53 |

| No | 85 | 48 |

| Partnership has formal agreement | ||

| Yes | 74 | 42 |

| No | 103 | 58 |

| Project developed evaluation instruments or measures | ||

| Yes | 85 | 48 |

| In process | 41 | 23 |

| No/don’t know | 52 | 29 |

| Who approved community participation in research | ||

| Individual | 52 | 29 |

| Community advisory board | 44 | 25 |

| Local community agency | 53 | 30 |

| Local government (tribal, health board, public health) | 40 | 22 |

| Local IRB (community or tribal) | 50 | 28 |

|

|

||

| M | SD | |

|

|

||

| Length of project in years | 2.7 | 2.1 |

| Length of partnership in years | 6.0 | 4.7 |

Note. IRB = institutional review board.

We then added three RIH “promising practices” of partnerships. One was added directly: budget sharing with community. We refined the other two: (a) values-based or research training or formal discussion topics; and (b) approvals of the project on behalf of the community (i.e., none, individual, community advisory board, local community agency, local or tribal government, health board, community institutional review board; recoded for this study as individual/none or others labelled as community approval).

Additional promising practices were identified from the increasing use of advisory boards (Eder et al., 2018), from expanding our RIH analysis of community stewardship (Oetzel, Villegas et al., 2015), and from our own case study data. These included (a) whether the project used a community advisory board separate from the project (yes/no), followed by five items on advisory board roles, such as whether the board identified research needs and priorities; (b) whether partners engage in regular self-reflection (yes/no) and six items on the extent of reflective practices, with a question about self-evaluation, collective reflection, and quality improvement; and (c) approval entity actions that promote community stewardship, for example, ensuring research is grounded in community perspectives and benefits the community (see Table 3 for items along with the psychometric properties of the scales; all were measured on a 6-point scale from not at all to complete extent). We translated both instruments into Spanish to reach community partners whose first language might not be English.

TABLE 3.

Principal Component Analysis for CBPR Partnership “Promising Practices” (n = 174)

| Practices | Component 1 | Component 2 | Cronbach’s α | M (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Practice #1: training/formal discussion topics (n = 174) | ||||

| 1a. Values/power topics | 0.86 | 2.52 (1.28) | ||

| Racism, sexism, and/or other forms of oppression | 0.93 | |||

| Cultural sensitivity or cultural humility | 0.83 | |||

| CBPR | 0.83 | |||

| Conflict resolution | 0.70 | |||

| 1b. Research issues topics | 0.91 | 3.56 (1.46) | ||

| Research methodologies | 0.93 | |||

| Research ethics and IRB | 0.95 | |||

| Practice #2: stewardship for community benefit (n = 95) | 0.88 | 4.44 (1.22) | ||

| Research ethics are followed | 0.54 | |||

| Research grounded in community culture/perspectives | 0.92 | |||

| Community’s voice is part of research | 0.92 | |||

| Community benefit | 0.85 | |||

| Communication to community and stakeholders | 0.87 | |||

| Practice #3: advisory group roles (n = 91) | 0.88 | 4.00 (1.12) | ||

| Strengthens community/academic collaborations | 0.86 | |||

| Develops plans to use findings for community benefit | 0.85 | |||

| Identifies research needs and priorities | 0.85 | |||

| Assists with sustainability planning | 0.80 | |||

| Consults on cultural issues | 0.79 | |||

Note. Component loadings less than 0.4 in magnitude are not displayed. CBPR = community-based; IRB, institutional review board; KI, key informant.

Members of the E2 national research team and Think Tank pretested both surveys, providing critique and feedback regarding the length of the survey, reading level and readability of items, the content and sequence of the measures and items, and, because these instruments were administered online, the usability of the online format. Minor revisions were made to phrasing of items and order of questions, although the overall survey was largely supported in its original form. This article will focus on data collected through the KIS, which provided information about the specific structural characteristics and practices present in the three different stages of the partnerships identified by their PIs. We categorized partnerships as early when PIs responded they were “planning grants or pilots to develop collaboration”; single project, when defined as an “ongoing partnership for a specific project”; and multiple project, when defined as an “established partnership that has worked on multiple projects together.” The length of time a partnership is together does not have clear definition in the literature. Therefore, we consulted with our Think Tank to determine that these categories were appropriate.

Data for the KIS was collected between September 2016 and March 2017. Letters were sent to PIs of identified projects inviting them to participate in the study and providing a gift card as incentive for participation. After the initial letter, up to three emails reminders were sent and up to two phone calls were made inviting them to participate in the KIS. A link was provided, and the survey was administered through an encrypted, online data management platform: REDCap (Patridge & Bardyn, 2018). The response rate for the KIS was 53% (199 of 377), excluding projects giving notification by phone or email that they did not meet the inclusion criteria. The analytic sample for the KIS was 179 cases that screened into the survey by identifying that they had community partners involved across multiple phases of the research process and submitting a completed survey.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed in SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 23 (IBM, Armonk, NY), and we calculated descriptive statistics, including frequencies and percentages, as appropriate. Pearson’s chi-square tests and McNemar’s test were used, respectively, to assess associations and concordance between categorical variables with Fisher’s test and the binomial probability test used as exact alternatives in cases of low expected cell counts (Pett, 2015). Principal component analysis (PCA) was used to identify components with an eigenvalue greater than 1 from the set of variables measuring promising practices, with direct oblimin rotation (Jolliffe, 2002). As described earlier, those promising practices were training and formal discussion on topics related to values and power, stewardship for community benefit, and advisory group roles. Finally, projects were divided into the three different stages of partnership funding, with Pearson’s chi-square tests also used to compare how partnerships in different stages used the practices, such as community advisory boards, reflective practice, and the entity of approval for community participation (see Table 4 for a full list of variables and analysis). One-way analysis of variance with Tukey’s test for post hoc pairwise comparisons was conducted to compare means between the three stages of partnerships and the promising practices PCA score. Scores for these promising practices were calculated as the mean of nonmissing component item scores from the PCA.

TABLE 4.

Partnership Practices by Partnership Stage (N = 175)

| Practice | Early-Stage Partnership n = 86 |

Single-Project Partnership n = 42 |

Multiple-Project Partnership n = 47 |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

|

| ||||

| Regular self-evaluation (n = 172) | 40 (48) | 25 (61) | 29 (62) | 0.19 |

| Community advisory board (n = 175) | 42 (49) | 23 (55) | 26 (55) | 0.71 |

| Entity approval for community participation (n = 175) | 0.03a | |||

| Individual/none indicated | 51 (59) | 17 (40) | 18 (38) | |

| Community | 35 (41) | 25 (60) | 29 (62) | |

|

|

||||

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | ||

|

|

||||

| Training/discussion topics (n = 174) | ||||

| Values/power (4 items) | 2.18 (1.16) | 2.58 (1.16) | 3.13 (1.38) | <.001b |

| Research issues topics (2 items) | 3.40 (1.46) | 3.56 (1.43) | 3.91 (1.44) | 0.15 |

| Stewardship for community benefit (5 items; n = 95) | 4.17 (1.35) | 4.25 (1.14) | 4.91 (0.96) | 0.01b |

| Advisory group roles (5 items; n = 91) | 3.71 (1.15) | 4.01 (1.07) | 4.48 (0.99) | 0.02b |

| Extent of reflective practices (6 items; n = 173) | 2.76 (1.21) | 3.00 (1.13) | 3.38 (1.33) | 0.02b |

| % budget shared with community (n = 154) | 25.58 (22.72) | 22.12 (17.11) | 38.78 (18.71) | <.001c |

| Length of time of partnership in years (n = 174) | 3.48 (2.52) | 6.98 (4.45) | 9.91 (5.05) | <.001d |

Comparison between early-stage and both single and multiple projects; single and multiple project partnerships had greater approval by community agencies compared with early stage partnership.

Pairwise comparison between early-stage and multiple-project partnerships; multiple projects had greater use of partnership practice compared with early-stage partnerships.

Pairwise comparisons between multiple-project partnerships and both early-stage and single-project partnerships; multiple project partnerships had a greater percentage of budget allocated to the community than either early-stage or single-project partnerships.

Pairwise comparisons between early-stage and single-project, and single-project and multiple-project partnerships; multiple-project partnerships had a longer time in partnership than did single-project partnerships, which had a longer time in partnership than early-stage partnerships

Results

Description of Structural Characteristics

We describe the analytic sample of 179 projects in Table 1. Nearly half (49%) of KIs identified that their project was initiated by a combination of both academic and community partners, and 47% were initiated only by academics. The key informants most commonly identified the partners involved in their research projects as individual community members (62%), community-based organizations (60%), and healthcare staff (54%). Nearly half of the projects in the sample were in the early stage (49%), with single-project partnerships (24%) and multiple-project partnerships (27%) approximately equally represented in the remainder of the sample. The average length of partnerships was six years, and the length of projects was approximately three years.

Intervention projects were the most common study type (60%), with 12% identified as dissemination and implementation projects. More than half (53%) reported a community advisory group separate from the partnership. Forty-two percent had a formal agreement for their partnership. Local community boards (30%) and individuals (29%) with the project were the most common entities to approve community participation in the research.

The characteristics of the projects from the sample outlined in Table 2 showed that projects worked with communities of low socioeconomic status (58%) and Black/African-American (57%) and Hispanic (45%) populations, with 36% of participants identifying additional population groups, such as older adults, rural populations, caregivers, youth/adolescents, and individuals with substance use disorders. Conversely, the PIs of sample projects more likely identified as White (73%), female (63%), and from immigrant communities (11%); 3% of PIs had low socioeconomic status, 8% of PIs were African American, and 8% of PIs being Hispanic/Latino. Racial and ethnic minority populations were of interest for projects at higher rates than they were represented as PIs for projects, with McNemar’s test giving p < .001 for each group of racial/ethnic minorities and an exact p-value of .09 for Asian Americans. Conversely, at least 75% racial/ethnic minority PIs headed a project that reported their own racial/ethnic minority as project population of interest.

TABLE 2.

Project (n = 179) and PI Characteristics (n = 118)a

| Characteristic | Project Population(s) of Interest | PI Group Demographics | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Race/ethnicity | n | % | n | % |

|

|

||||

| American Indian/ Alaska Native | 56 | 31 | 11 | 9 |

| Asian | 32 | 18 | 11 | 9 |

| Black or African American | 102 | 57 | 9 | 8 |

| Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander | 19 | 11 | 1 | 1 |

| White | 77 | 43 | 86 | 73 |

| Hispanic or Latino | 81 | 45 | 10 | 8 |

| Population group | ||||

| LGBTQ | 9 | 5 | 7 | 6 |

| Low socioeconomic status | 104 | 58 | 4 | 3 |

| Persons with disabilities | 17 | 10 | 3 | 3 |

| Immigrants | 22 | 12 | 13 | 11 |

| Refugees | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Additional population group(s) | 64 | 36 | 3 | 3 |

| None of the above indicated | 10 | 6 | ||

| Gender identity | ||||

| Male | 43 | 37 | ||

| Female | 73 | 63 | ||

| Different identity | n/a | n/a | ||

| None of the above indicated | n/a | n/a | ||

Note. LGBTQ = lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, questioning; PI = principal investigator.

n = 118 for PI demographics due to missing data.

Promising Practices

The PCA demonstrated the importance of three promising practices of CBPR partnerships: (a) practice #1—training/formal discussion on values/power topics and research topics (confirmed from previous research [Oetzel, Zhou et al., 2015; Pearson et al., 2015]); (b) practice #2—stewardship for community benefit; and (c) practice #3—advisory group roles (see Table 3 for loadings, Cronbach’s alpha, and M/SD). For the first practice, providing training/formal discussion on topics of values/power loaded onto one component accounting for 61% of the variance. Training/formal discussion of research topics loaded onto a second component accounting for 18% of the variance. For the second practice, a single component involving the practice of stewardship for the community benefit accounted for 69% of the variance. For the third practice, the five items identifying key advisory group roles all loaded onto a single component accounting for 69% of the variance. The number of cases included in these PCA calculations differ slightly from the number of cases with component scores listed in Table 3 by between three to eight cases due to missing values when, due to survey item branching logic, some participants did not complete certain item responses.

Stage of Partnership

Table 4 summarizes the differences in partnership practices between the three funding stages of partnership. Individual approvals for community participation were more common in early-stage partnerships (59%), whereas more established partnerships with multiple partners relied on structural approval by community entities (62%; χ2(2) = 7.03, p = .03). Training on issues of values and power was higher among multiple-project versus early-stage partnerships (t(171) = 4.28, p < .001). Among the three additional promising practices, there were differences between early-stage and multiple-project stage partnerships related to stewardship for community benefit (t(92) = 2.67, p = .02), advisory group roles (t(88) = 2.83, p = .02), and the use of reflective practices (t(170) = 2.79, p = .02). The practice of sharing a percentage of the project budget with the community showed differences between multiple-project partnerships and both early-stage (t(151) = 3.65, p = .001) and single-project partnerships (t(151) = 3.41 p = .002), but not between early-stage and single-project partnerships (t(151) = −0.83, p = .69). Multiple-project partnerships reported sharing a larger percentage of the project budget than did early-stage partnerships and single-project partnerships.

Discussion

Our analyses of the E2 sample demonstrate validation and advances in the field since the previous 2009 RIH study (Oetzel, Zhou et al., 2015; Pearson et al., 2015), yet also suggest continued challenges. Although the practices of community-level approvals and training on power/values have been documented previously, to our knowledge, this analysis by stage showed significant differences for the first time, with longer-term partnerships being more responsive to community. We also expanded our attention to community benefit beyond who approved the study by asking, about actions that promote community stewardship and advisory board roles. These practices (training about value/power and research, stewardship for community benefit, and community advisory boards and their roles), along with the capacity to engage in reflection and self-evaluation, have been shown to improve not only the way in which academic and community team members build trust and strengthen relationship, but also how partnerships achieve outcomes to which they are aspiring (Oetzel et al., 2018).

Challenges still relate to inequities of federally funded support for community partners compared with academic partners. As might be expected, multiple-project, longer-term partnerships allocated more of their budget to community than earlier-stage partnerships. Only 3% of projects were initiated by community partners, with less than half having formal agreements for the partnership. These structural practices of agreements and shared budgets become important for promoting equity within the partnership and are engagement practices that early-stage partnerships can incorporate during the initial partnership planning and discussions.

Another challenge is that academic partners still do not represent the racial/ethnic diversity of populations served. This was revealed most starkly in comparing projects focusing on Black/African-American populations (57%) and the racial/ethnic identity of PIs (e.g., 2.5 % Black/African American vs. 73% White). Although racial/ethnic composition alone does not determine whether a CBPR project is effective, academic PIs of color have demonstrated commitment to their communities and addressing structural inequities, thus increasing the likelihood of having shared values (Belone, Griffith, & Baquero, 2017; Drame & Irby, 2016; Muhammad et al., 2015).

Limitations of this study included the cross-sectional snapshot of projects, with partnerships excluded if they were temporarily unfunded or funded by foundations. This sample, however, had a wide range of grant funding, including newer PCORI projects. Because responses came from PIs, there may be limitations regarding social desirability bias. Furthermore, PIs may not be aware of collaborations among their community partners prior to the currently funded project; declared early-stage projects might also have longer, unfunded relationships. This could explain better practices in the partnership than the professed stages of their project. It may also be important in the future to separate out questions on the length of relationships from the actual project(s) funded, and how partners view their own partnership stage. Despite these potential challenges, we found differences between multiple-project (mean of almost 10 years) and early-stage (mean of 3.5 years) partnerships on most promising practices— an important indication of capacity of partners over time to embrace equality and stronger stewardship of community benefit.

Conclusion

This study represents a rigorous survey of 179 federally supported CBPR projects from 2015 and gave us the opportunity to validate and extend our knowledge. With greater understanding of promising practices, nurse scientists can more readily adopt the benefits outlined of CBPR. Additional support for using CBPR can be found in online CBPR toolkits and courses, which encourage nurse researchers to embrace high-level engagement and a commitment to equity with community members, patients, and health systems.

Acknowledgement:

We gratefully acknowledge the contribution of partners who are affiliated with the Engage for Equity (E2) study. We thank our research partners (University of New Mexico Center for Participatory Research, University of Washington Indigenous Wellness Research Institute, Community Campus Partnerships for Health, National Indian Child Welfare Association, University of Waikato, and RAND Corporation), and the national Think Tank of community and academic CBPR experts. Partial funding for this study is from the National Institute of Nursing Research: 1 R01 NR015241–01A1. We thank Amanda Hefferman, MSN, CNM for assistance with statistical analysis, and Anne Mattarella, MA, ELS for assistance with copy editing. We appreciate all participants (academic and community partners) who so generously answered all the questions asked of them in the survey.

The authors would like to gratefully acknowledge the contribution of partners who are affiliated with the Engage for Equity (E2) study.

The authors would like to thank their research partners (University of New Mexico Center for Participatory Research, University of Washington Indigenous Wellness Research Institute, Community Campus Partnerships for Health, National Indian Child Welfare Association, University of Waikato, and RAND Corporation), and the national Think Tank of community and academic CBPR experts.

The authors also thank Amanda Hefferman, MSN, CNM, Research Assistant, College of Nursing, University of New Mexico for assistance with statistical analysis, and Anne Mattarella, MA, ELS, Technical Editor, College of Nursing, University of New Mexico for assistance with copy editing.

The authors appreciate all participants (academic and community partners) who so generously answered all the questions asked of them in the survey.

Partial funding for this study is from the National Institute of Nursing Research from R01NR015241.

The University of New Mexico Health Science Center institutional review board approved all research reported in this manuscript.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Ethical Conduct of Research: The University of New Mexico Health Science Center institutional review board approved all research reported in this manuscript.

Contributor Information

Elizabeth Dickson, University of New Mexico, College of Nursing, Albuquerque, NM.

Maya Magarati, University of Washington, Department of Sociology, Seattle, WA.

Blake Boursaw, University of New Mexico, College of Nursing, Albuquerque, NM.

John Oetzel, University of Waikato, Waikato Management School, Hamilton, New Zealand.

Carlos Devia, City University of New York, School of Public Health and Health Policy, New York, NY.

Kasim Ortiz, University of New Mexico, Department of Sociology, Albuquerque, NM.

Nina Wallerstein, University of New Mexico, College of Population Health, Albuquerque, NM.

References

- Anderson NLR, Lesser J, Oscós-Sánchez MA, Piñeda DV, Garcia G, & Mancha J (2014). Approaches to community nursing research partnerships: A case example. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 25, 129–136. doi: 10.1177/1043659613515721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Averill J (2008). Community partnership through a nursing lens. In Minkler M & Wallerstein N (Eds.), Community-based participatory research for health: From process to outcomes (2nd ed., pp. 431–434). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Belone L, Griffith DM, & Baquero B (2017). Academic positions for faculty of color: Combining life calling, community service, and research. In Wallerstein N, Duran B, Oetzel J, & Minkler M (Eds.), Community-based participatory research for health: From process to outcomes (3rd ed., pp. 265–271). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Cusack C, Cohen B, Mignone J, Chartier MJ, & Lutfiyya Z (2018). Participatory action as a research method with public health nurses. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 74, 1544–1553. doi: 10.1111/jan.13555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csiernik R, O’Regan T, Forchuk C, & Rudnick A (2018). Nursing students’ perceptions of participatory action research. Journal of Nursing Education, 57, 282–286. doi: 10.3928/01484834-20180420-05 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duran B, Wallerstein N, Avila MM, Belone L, Minker M, & Foley K (2013). Developing and maintaining partnerships with communities. In Israel BA, Eng E, Schulz AJ, & Parker EA (Eds.) Methods for community-based participatory research for health. (2nd ed., pp. 43–68). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Drame ER, & Irby DJ (Eds.). (2016). Black participatory research: Power, identity, and the struggle for justice in education. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Eder MM, Evans E, Funes M, Hong H, Reuter K, Ahmed S, . . . Wallerstein N (2018). Defining and measuring community engagement and community-engaged research: Clinical and translational science institutional practices. Progress in Community Health Partnerships: Research, Education, and Action, 12, 145–156. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2018.0044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster J, Gossett S, Burgos R, Cáceres R, Tejada C, Dominguez García L, . . . Perez LJ (2015). Improving maternity care in the Dominican Republic: A pilot study of a community-based participatory research action plan by an international healthcare team. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 26, 254–260. doi: 10.1177/1043659614524252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freire P (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed (Ramos MB, Trans.). New York, NY: Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- Furman L, Matthews L, Davis V, Killpack S, & O’Riordan MA (2016). Breast for success: A community-academic collaboration to increase breastfeeding among high-risk mothers in Cleveland. Progress in Community Health Partnerships: Research, Education, and Action, 10, 341–353. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2016.0041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grady PA, & McIlvane JM (2016). The domain of nursing science. In Henly SJ (Ed.), Routledge international handbook of advanced quantitative methods in nursing research (pp. 3–14). Abingdon, UK: Routledge/Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Holliday CE, Wynne M, Katz J, Ford C, & Barbosa-Leiker C (2018). A CBPR approach to finding community strengths and challenges to prevent youth suicide and substance abuse. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 29, 64–73. doi: 10.1177/1043659616679234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ismail MM, Gerrish K, Salway S, & Chowbey P (2014). Engaging minorities in researching sensitive health topics by using a participatory approach. Nurse Researcher, 22, 44–48. doi: 10.7748/nr.22.2.44.e1268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagosh J, Bush PL, Salsberg J, Macaulay AC, Greenhalgh T, Wong G, . . . Pluye P (2015). A realist evaluation of community-based participatory research: Partnership synergy, trust building and related ripple effects. BMC Public Health, 15. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1949-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jolliffe IT (2002). Principal component analysis (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Springer-Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Kastelic SL, Wallerstein N, Duran B, & Oetzel JG (2017). Socio-ecologic framework for CBPR: Development and testing of a model. In Wallerstein N, Duran B, Oetzel J, & Minkler M (Eds.), Community-based participatory research for health: Advancing social and health equity (3rd ed., pp. 77–94). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly PJ (2005). Practical suggestions for community interventions using participatory action research. Public Health Nursing, 22, 65–73. doi: 10.1111/j.0737-1209.2005.22110.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khodyakov D, Stockdale S, Jones F, Ohito E, Jones A, Lizaola E, & Mango J (2011). An exploration of the effect of community engagement in research on perceived outcomes of partnered mental health services projects. Society and Mental Health, 1, 185–199. doi: 10.1177/2156869311431613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leviton LC, & Green LW (2017). Funding in CBPR in U.S. government and philanthropy. In Wallerstein N, Duran B, Oetzel J, & Minkler M (Eds.), Community-based participatory research for health: From process to outcomes (3rd ed., pp. 363–367). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Lucero J, Wallerstein N, Duran B, Alegria M, Greene-Moton E, Israel B, . . . White Hat ER (2018). Development of a mixed methods investigation of process and outcomes of community-based participatory research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 12, 55–74. doi: 10.1177/1558689816633309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muhammad M, Wallerstein N, Sussman AL, Avila M, Belone L, & Duran B (2015). Reflections on researcher identity and power: The impact of positionality on community based participatory research (CBPR) processes and outcomes. Critical Sociology, 41, 1045–1063. doi: 10.1177/0896920513516025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Nursing Research. (2010). Minutes of the national advisory council for nursing research: September 14–15, 2010. Retrieved from https://www.ninr.nih.gov/aboutninr/nacnr/council-minutes-sept-2010

- Nguyen-Truong CKY, Nguyen KQ, V., Nguyen TH, Le T, V., Truong AM, & Rodela K (2018). Vietnamese American women’s beliefs and perceptions about breast cancer and breast cancer screening: A community-based participatory study. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 29, 555–562. doi: 10.1177/1043659618764570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oetzel JG, Wallerstein N, Duran B, Sanchez-Youngman S, Nguyen T, Woo K, . . . Alegria M, (2018). Impact of participatory health research: A test of the community-based participatory research conceptual model. BioMed Research International. doi: 10.1155/2018/7281405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oetzel JG, Villegas M, Zenone H, White Hat ER, Wallerstein N, & Duran B (2015). Enhancing stewardship of community-engaged research through governance. American Journal of Public Health, 105, 1161–1167. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oetzel JG, Zhou C, Duran B, Pearson C, Magarati M, Lucero J, . . . Villegas M (2015). Establishing the psychometric properties of constructs in a community-based participatory research conceptual model. American Journal of Health Promotion, 29, e188–e202. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.130731-QUAN-398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patridge EF, & Bardyn TP (2018). Research electronic data capture (REDCap). Journal of the Medical Library Association, 106, 142–144. doi: 10.5195/jmla.2018.319 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson CR, Duran B, Oetzel J, Margarati M, Villegas M, Lucero J, & Wallerstein N (2015). Research for improved health: Variability and impact of structural characteristics in federally funded community engaged research. Progress in Community Health Partnerships: Research, Education, and Action, 9, 17–29. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2015.0010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersson P, & Blomqvist K (2011). Sense of security–searching for its meaning by using stories: A participatory action research study in health and social care in Sweden. International Journal of Older People Nursing, 6, 25–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-3743.2010.00211.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pett MA (2015). Nonparametric statistics for health care research: Statistics for small samples and unusual distributions (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Portillo CJ, & Waters C (2004). Community partnerships: The cornerstone of community health research. In Fitzpatrick JJ (Ed.), Annual review of nursing research, Vol. 22 (pp. 315–329). New York, NY: Springer Publishing. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shattell MM (2014). Emerging theories for practice critical, participatory, ecological, and user-led: Nursing scholarship and knowledge development of the future. ANS: Advances in Nursing Science, 37, 3–4. doi: 10.1097/ANS.0000000000000012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein N, & Duran B (2010). Community-based participatory research contributions to intervention research: The intersection of science and practice to improve health equity. American Journal of Public Health, 100, S40–S46. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.184036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein N, Duran B, Oetzel JG, & Minkler M (2017). On community-based participatory research. In Wallerstein N, Duran B, Oetzel JG, & Minkler M (Eds.), Community-based participatory research for health: Advancing social and health equity (3rd ed., pp. 3–16). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein N, Oetzel J, Duran B, Tafoya G, Belone L, & Rae R (2008). What predicts outcomes in CBPR. In Minkler M, & Wallerstein N (Eds.), Community-based participatory research for health: From process to outcomes (2nd ed., pp. 371–392). San Francisco, CA, Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins CH, Spofford M, Williams N, McKeever C, Allen S, Brown J, . . . Strelnick AH (2013). Community representatives’ involvement in clinical and translational science awardee activities. Clinical and Translational Science, 6, 292–296. doi: 10.1111/cts.12072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zandee GL, Bossenbroek D, Slager D, Gordon B, Ayoola AB, Doornbos MM, & Lima A (2015). Impact of integrating community-based participatory research into a baccalaureate nursing curriculum. Journal of Nursing Education, 54, 394–398. doi: 10.3928/01484834-20150617-07 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]