Abstract

Manganese oxide-based catalysts have attracted extensive attention due to their relatively low cost and remarkable performance for removing VOCs. In this research, we used the Pechini method to synthesize manganese-cerium-nickel ternary oxide catalysts (MCN) and evaluated the effectiveness of catalytic destruction of formaldehyde (HCHO) and ozone at room temperature. FeOx prepared by the impregnation method was applied to modify the catalyst. After FeOx treatment, the catalyst represented the best performance on both HCHO destruction and ozone decomposition under dry conditions and exhibited excellent water vapor resistance. The as-prepared catalysts were next characterized via H2-temperature programmed reduction (H2-TPR), temperature programmed desorption of O2 (O2-TPD), and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), and the results demonstrated that addition of FeOx increased Mn3+ and Ce3+ concentrations, oxygen vacancies and surface lattice oxygen species, facilitated adsorption, and redox properties. Based on the results of in situ diffuse reflectance infrared Fourier transform spectrometry (DRIFTS), possible mechanisms of ozone catalytic oxidation of HCHO were proposed. Overall, the ternary mixed-oxide catalyst developed in this study holds great promise for HCHO and ozone decomposition in the indoor environment.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11356-022-24543-y.

Keywords: Mn-Ce-Ni ternary oxide catalysts, FeOx, Formaldehyde, Ozone catalytic oxidation

Introduction

In the winter of 2019, a novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) was detected in China and rapidly spreading as a global pandemic. China was the first country which was determined to have lockdown human and industrial activities, and the consequence was enormous. Specifically, the lockdown results in people spending more time in the indoor environment, causing them to be highly exposed to indoor air pollutants (Du et al. 2020). Especially, people might have to prepare their meals at home rather than eating out. Jung et al. (2021) pointed out that a significant amount of formaldehyde (HCHO) was generated in typical home cooking procedures. Additionally, smoking was also an important source of indoor formaldehyde. During the lockdown, the frequency of nonsmokers exposed to second-hand smoke may also increase. Long-term exposure to low-concentration HCHO may increase the prevalence of nasopharyngeal cancer and leukemia (Nielsen et al. 2017). During the past few decades, researchers have developed effective methods such as adsorption, photocatalysis, and nonthermal plasma for removing HCHO from gas streams. However, these technologies have encountered some challenges, such as low efficiency, the formation of unwanted products, and catalyst deactivation. To solve these bottlenecks, ozone catalytic oxidation (OZCO) with the advantages of low cost, high removal efficiency, and less byproduct formation has been developed (Zhu et al. 2017a). With strong oxidation capability of ozone and oxygen radicals, HCHO could entirely oxidize into harmless water and CO2 at room temperature. However, ozone is a double-edged sword (Li et al. 2018). A previous study indicated that exposure to low-concentration ozone (~ 51 ppb) may cause respiratory illness and cardiovascular mortality (Cao et al. 2019). Consequently, simultaneous removal of HCHO and ozone is essential to protect human health and the environment when OZCO is applied.

Noble metal catalysts show good catalytic performance, but they are expensive and tend to be deactivated (Bao et al. 2020). Among the transition metal oxides, MnOx, CeO2, and NiO-based oxides as potential alternatives have attracted increasing attention due to their low cost and high thermal stability. Zhang et al. (2019) prepared MnCeOx catalysts by the Pechini method; Mn is introduced into the CeO2 structure to form Mn-Ce solid solution, which revealed excellent catalytic activity. Solid solutions are alloy phases in which solute atoms are dissolved into solvent lattices while remaining solvent types. The phase boundaries of bimetallic interfaces can provide abundant lattice mismatches, distortions, and defects, which will provide abundant oxygen vacancies and active sites (Wang et al. 2018). Gong et al. (2019a) synthesized heterostructure Ni/NiO nano-catalysts via solgel method and displayed excellent decomposition rate for ozone since NiO promotes the transfer of active oxygen to the surface. However, these catalysts have low humidity resistance; thus, it should be further improved for real application in the field. FeOx is a common MnOx doping material due to its high specific surface area (SBET), great stability, and high capability for electron transfer. Zhang et al. (2014) indicated that addition of FeOx into Mn2O3 reveals excellent activity toward NO removal thanks to its high SBET and abundant Mn3+, Fe3+, and chemisorbed oxygen species. Besides, strong interaction between Fe and Mn facilitated the catalyst durability and humidity resistance (Lian et al. 2015, Wang et al. 2020b). At present, there are few reports on the simultaneous destruction of HCHO and ozone for indoor air quality management.

In this study, we synthesized a series of novel MnCeNiOx catalysts by the simple Pechini method, and then modified it by FeOx to further improve the catalytic activity for HCHO destruction at room temperature. It was found that the addition of FeOx contributed to a better performance in HCHO oxidation. The FeOx-MnCeNiOx samples were characterized by various techniques, including N2 physisorption, XRD, SEM, XPS, H2-TPR, O2-TPD, and TGA. The high performance was correlated with a high ratio of Mn3+/Mn4+ and Ce3+/Ce4+ and abundant surface-adsorbed oxygen species. The effects of initial O3 concentration and water vapor with the catalytic performance were also investigated to demonstrate fundamental insights into the superior activity of the FeOx-MnCeNiOx catalysts. Based on in situ DRIFTS results, a viable mechanism of formaldehyde decomposition is presented. This study provides a high-activity, economical, environment-friendly, and simple catalytic method for the degradation of low-concentration HCHO. This work offers a valuable route to simultaneously catalytic destruction of HCHO and ozone for indoor air quality environmental management.

Experimental

Synthesis of MnxCeNiOx catalysts

All reagents were of analytical grade and without purification. Porous MnxCeNiOx catalysts were prepared by the Pechini method. Stoichiometric amounts of Mn(NO3)2•6H2O, Ni(NO3)7•6H2O and Ce(NO3)3•6H2O were dissolved in deionized water under ultrasonication to obtain a homogeneous solution and placed in a beaker with magnetic stirrer; then citric acid and ethylene glycol were added to the solution as chelators. Afterwards, the solution was stirred continuously at 80 °C until it formed a stabilized pale green gel. After drying at 100 °C overnight, it turned into a puffy and porous dry solid. Finally, the fresh MnCeNiOx catalysts were obtained by calcination at 500 °C in air for 6 h at a rate of 10 °C/min. The final products are named as MCN and M2CN based on varying Mn/Ce atomic ratios (Mn/Ce = 1:1, 2:1), respectively. Pure MnO2, CeO2, and NiO was synthesized by the same Pechini method.

Synthesis of FeOx-MnxCeNiOx catalysts

FeOX were prepared following a previous work (Chen et al. 2014). In brief, stoichiometric amounts of Fe(NO3)3•9H2O were dissolved in deionized water under ultrasonication to obtain a homogeneous solution. Afterwards, Na2CO3 was dropwise added into the solution under vigorous stirring at 60 °C until the pH value stabilized at 8. After aging for 4 h, MCN was soaked in the resulting precipitate and dried at 60 °C for 18 h. Then, the final product was kept at 200 °C for 4 h to obtain fresh FeOx-MnCeNiOx catalyst which is denoted as F-MCN. Pure FeOx was synthesized by the same method. The catalysts prepared were then ground and sieved to a particle size of 30–70 mesh before conducting catalyst characterization and activity test. The catalysts obtained were then characterized accordingly as described in the supplementary information.

Activity test

The schematic of the experimental setup for evaluating HCHO removal via OZCO is shown in Fig. S1. The inlet HCHO concentration was controlled by adjusting N2 flow rate and water bath temperature. Water vapor was produced by passing N2 through a water-containing bottle, and before entering the reactor, the relative humidity (RH) was measured by a humidity sensor (Center 310 RS-232, Taiwan). HCHO was measured by Fourier transform-infrared spectroscopy (Thermo Nicolet 6700, USA). The concentration of outlet CO2 was analyzed by CO2 Analyzer (Thermo 41C, USA), and the outlet CO concentration was measured by the Testo flue gas analyzer (Testo 350, Germany). Ozone was generated by a commercial ozone generator (Dean’s OW-K2/A-O, Taiwan), and the outlet ozone concentration was analyzed using an ozone analyzer (ITRI CMS/HOA, Taiwan). The equations for calculating HCHO mineralization rate and ozone decomposition are shown in supporting information.

Results and discussion

Crystal structures and morphology analysis

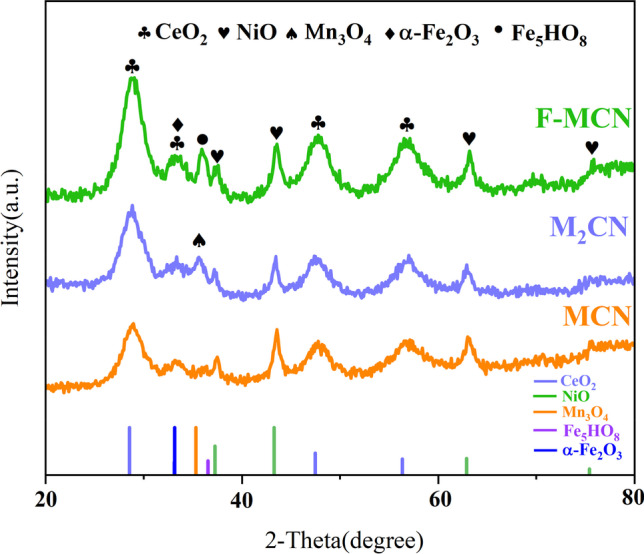

The crystal structures of the original MCN, M2CN, and FeOx-treated MCN samples were examined by XRD, as presented in Fig. 1. The diffraction peaks at 2θ = 28°, 33°, 47°, and 56° can be classified as (110), (200), (220), and (311) planes of fluorite-type CeO2 (PDF#43–1002). The position of the diffraction peak is slightly shifted, and the diffraction angle becomes larger compared with the pure CeO2 (Zhang et al. 2019), indicating that Mn ions are added into the CeO2 lattice to form Mn-Ce solid solution. In addition, no obvious peaks of Mn oxides are found in MCN and F-MCN catalysts, which means Mn-Ce solid solution was formed or Mn ions were well dispersed over the catalyst surface. The formation of solid solution will induce more surface defects and surface oxygen species, which is conducive to the adsorption and decomposition of O3 and HCHO molecules under the catalyst surface. The appearance of the peak at 35° is attributed to Mn3O4 (PDF#13–0162) as the content of the Mn ratio is increased. Moreover, the peaks of 37°, 43°, 63°, and 75° were the characteristic peaks of NiO (PDF#47–1049). The FeOx modified catalyst exhibited weak and broad diffraction lines at 33° and 36°, which could be ascribed to Fe5HO8 ·4H2O (PDF#16–0653) or ɑ-Fe2O3 (PDF#33–0664) (Daniells et al. 2005; Hutchings et al. 2006). Among them, the diffraction peak at 35°could be attributed to Fe3Mn3O8. Chen et al. (2011) indicated the Fe3Mn3O8 could greatly enhance the catalytic activity on NOx removal. The strength of the peaks was enhanced by FeOx modification, revealing that the crystallinity increased with the modification. Generally, the average grain size (D) of the catalyst is given by the following Scherrer’s formula [51].

| 1 |

Fig. 1.

XRD patterns of MCN, M2CN, and F-MCN, respectively

where K is a constant (0.89); λ is the X-ray wavelength (0.154056 nm); β is the half-peak width; and θ is the diffraction angle. The as-calculated grain sizes of MCN, M2CN, and F-MCN are 5.175 nm, 7.1226 nm, and 4.815 nm, respectively. According to previous studies, the F-MCN catalyst has the smallest particle size, which can have a larger SBET (Bariki et al. 2020).

To understand the overall microstructural characteristics differences between as-synthesized catalyst, the N2-sorption isotherms were presented in Fig. S2, which are well-defined IV-type isotherms with a typical-type H3 hysteresis loop, indicating the presence of mesopores, along with the generated of mesopores which could produce abundant oxygen vacancies to facilitate HCHO oxidation. The SBET of MCN, M2CN, and F-MCN are 119, 70, and 140 m2/g, respectively. Compared with the MCN catalyst, introduction of FeOx increases the SBET and pore volume, which may be due to the formation of ferrihydrite and hematite under high calcination temperature (Chen et al. 2014). On the other hand, excessive addition of Mn element to catalyst results in a significant reduction of SBET and pore volume, indicating partial blocking of mesopores by Mn particles.

Further, the structure of MCN, M2CN, and F-MCN catalysts was investigated by Raman spectra, as presented in Fig. 2. All three as-prepared catalysts displayed a strong peak at 642 cm−1, which is attributed to fluorite F2g mode of CeO2. The appearance of a broad band ranging from 500 to 650 cm−1 is observed after the incorporation of Ni and can be attributed to the interaction between Ce and Ni, forming a mixed crystal; thus generation of oxygen vacancies must be accompanied to (Chagas et al. 2016). The band appearance from 500 to 650 cm−1 corresponds to the strong interaction between Ce and Mn to forming the Mn-Ce solid solution. The strong interaction will benefit the formation of oxygen vacancies due to the charge neutrality. The band at 365 cm−1 for M2CN belongs to the out-of-plane bending modes and symmetric stretching of Mn2O3 groups. After FeOx modification, the appearance of the peak at 310 cm−1 can be observed and attributed to hematite (α-Fe2O3). Raman spectra and XRD results suggest that FeOx has been successfully added to the catalyst to enhance the interaction between Mn-Ce and Ce-Ni mixed crystal, resulting in more oxygen vacancies.

Fig. 2.

Raman spectra of the MCN, M2CN, and F-MCN catalysts

To further investigate the morphology and microstructure of the as-prepared catalysts, SEM images of MCN, M2CN, and F-MCN were obtained, as shown in Fig. S3. It was observed that all three catalysts were mainly composed of block morphology with a rough surface and porous structure. And it can be seen that some fine NiO particles adhere to the surface of CeO2, and these particles have no specific morphology. The diameter of the nanoparticles was 1.5–1.9 μm accompanied by some small pieces with a diameter of 100 nm, besides a portion of the NiO particles agglomerate into spheres with a diameter of 300 nm. Meanwhile, as shown in Fig. S3b, for M2CN with the excessive doping of Mn ions, some lamellar petals attached to their surface appear, and these petals do not cluster into balls. For F-MCN, as shown in Fig. S3c, the metal oxides were highly dispersed under the surface of catalyst, which may be due to the partial sintering by secondary calcination in the preparation of FeOx.

Catalyst elemental analysis

The chemical composition of surface elements of MCN, M2CN, and F-MCN was determined through XPS, as shown in Fig. 3. Fe 2p spectra can be fitted into two peaks at 710.1 and 712.5 eV, which correspond to Fe2+ and Fe3+, respectively. Moreover, a satellite peak at around 718.0 eV was observed, which can be corresponding to Fe2O3 (Liu et al. 2018). Fe3+ is beneficial to the formation of surface hydroxyl which could improve the redox property of catalyst (Chen et al. 2014). The new species generated with Fe2+ was known as a main reason for the enhancement of chemisorbed oxygen (Wang et al. 2020a). Fe2+ and Fe3+ were both beneficial to the catalytic decomposition of HCHO.

Fig. 3.

XPS patterns of as-prepared catalyst for a Fe 2p, (ɑ) is MCN, (β) is M2CN, (γ) is F-MCN. b Mn 2p. c Ce 3d. d O1s, respectively

For the Mn species in the mixed metal oxide, it can be divided into Mn3+ (about 641.8 eV) and Mn4+ (about 642.7 eV), as shown in Fig. 3b. After modification with FeOx, the Mn3+/Mn4+ ratio increased significantly from 1.23 to 1.33 (Table 1). It is generally recognized that oxygen vacancies will be generated when Mn3+ exists in mixed metal oxide due to the maintained charge neutrality, based on the following reaction:

Table 1.

BET surface areas, pore volumes, average pore sizes, and elemental compositions of as-prepared catalysts

| Catalyst | SBET (m2/g) | SBETa (m2/g) | Dpore (nm) | Dporea (nm) | Vpore (cm3/g) | Vporea (cm3/g) | Surface atom ratio | Fe/Mn atom ratio | Mn/Ce/Ni atom ratio | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mn3+/Mn4+ | Ce3+/Ce4+ | Oads/Olatt | ICP-OES | XPS | ICP-OES | XPS | |||||||

| MCN | 119 | 113 | 4.66 | 4.68 | 0.14 | 0.13 | 1.23 | 0.34 | 0.22 | - | - | 1:1.09:0.98 | 1:1.07:0.96 |

| M2CN | 70 | 59 | 6.11 | 8.25 | 0.11 | 0.09 | 1.57 | 0.27 | 0.18 | - | - | 2:1.08:1.12 | 2:0.97:0.99 |

| F-MCN | 140 | 136 | 4.36 | 5.1 | 0.16 | 0.12 | 1.33 | 0.63 | 0.35 | 0.901 | 0.88 | 1:1.03:1.07 | 1:0.95:0.92 |

a: Used catalyst

where □ represents the oxygen vacancy site (Li et al. 2018).

Surface-active oxygen species derived from oxygen vacancies can directly participate in and become conducive to HCHO oxidation (Ye et al. 2022). Meanwhile, the addition of FeOx could induce the enhancement of Mn4+ amount (Wang et al. 2020b). Mn4+ are more conducive to the decomposition reaction over Mn-based catalysts (Chang et al. 2018). As a result of the formation of Fe–Mn solid solution, the incorporation of Fe affected the Mn ion electron state, thus leading the binding energy to exhibit a declining tendency.

Regarding the spectra of Ce 3d, five peaks at 881 eV, 883 eV, 899 eV, and 902 eV could be ascribed to Ce3+, while characteristic peaks of Ce4+ present at 882 eV, 888 eV, 897 eV, 900 eV, 907 eV, and 916 eV (Jiang et al. 2020). The atomic ratios of Ce3+/Ce4+ over MCN and F-MCN are 0.34 and 0.63, respectively (Table 1). In general, the oxygen vacancies will be generated when the Ce4+ transforms into nonstoichiometric Ce3+.

Therefore, the relative concentration of oxygen vacancies was usually proportional to the concentration of Ce3+ cations (Li et al. 2020).

The Ni 2p spectra of as-prepared catalysts were divided into three peaks at 852 eV, 857 eV, and 870 eV which were attributed to Ni0 (Song et al. 2017), respectively (Fig. S4). And the peak at 878 eV and 880 eV is corresponding to Ni2+ (Fang et al. 2019), indicating the existence of both NiO and metallic Ni in catalysts.

The O 1 s spectrum shows that the peaks at binding energies of 529 eV corresponded to lattice oxygen, while those at 531 eV was corresponding to the surface adsorbed oxygen species (Li et al. 2020), as shown in Fig. 3e. The atomic ratios of Oads/Olatt over MCN and F-MCN are 0.22 and 0.35, respectively (Table 1). Similarly, surface-adsorbed oxygen species usually adsorb on oxygen vacancy. These results illustrate that the F-MCN catalyst prepared possesses higher Mn3+/Mn4+, Ce3+/Ce4+ ratios, and extremely abundant surface-adsorbed oxygen species compared with MCN and M2CN, suggesting that modification with FeOx increases the content of oxygen vacancies.

The Fe, Mn, Ce, and Ni contents of as-synthesized catalysts were investigated by ICP-OES, as shown in Table 1. For MCN and M2CN, the ICP results demonstrate that the Mn, Ce, and Ni ratio is close to the theoretical value but not identical, while considering the experimental errors, such a deviation is acceptable. For F-MCN, after FeOx treatment, the intensities of Mn, Ce, and Ni signals were greatly reduced, and simultaneously a new signal of Fe appeared, which proved that Fe entered the catalyst and four elements are almost uniformly distributed in the catalysts. The strong interaction of Fe generated the reduction of Mn, Ce, and Ni ratio. The uniform distribution of the four elements will facilitate the formation of Fe–Mn and Mn-Ce solid solutions.

Chemisorption measurements

The H2-temperature programmed reduction profiles of MCN, M2CN, and F-MCN catalysts are measured to evaluate their reducibility, as presented in Fig. 4a. The H2-TPR profile of MCN could be divided into two principal reduction peaks, i.e., a little peak at 264 °C and the other stronger peak at 417 °C. The lower-temperature peak may be attributed to the reduction of MnO2/Mn2O3 to Mn3O4 (Liu et al. 2017), in which phase was also detected in XRD results. The higher-temperature peak was corresponding to the reduction of NiO particles to Ni0 (Chagas et al. 2016). Meanwhile, Mn3O4 will further reduce to MnO at 350–400 °C, thus enhancing H2 consumption in higher-temperature peak (Ma et al. 2020). Besides, there were no obvious peaks of CeO2 observed, which indicates that the reduction of Ce4+ accompanied with the reduction of Mn3+. The results demonstrated that the mobility of O atoms was increased when Mn ions were induced into the CeO2 lattice (Zhang et al. 2019). After addition of FeOx, the catalyst reveals three principal reduction peaks. The lower-temperature demonstrates two reduction peaks located at 240 and 285 °C, which were divided into surface oxygen species and MnO2 reduction. The higher-temperature peak was attributed to the reduction of Fe and Ni species (Song et al. 2017). The reduction peaks of Ni species moved towards lower temperature due to the addition of FeOx generated additional oxygen vacancies and facilitated the redox of catalysts. In addition, the peak area for F-MCN was significantly larger than that for MCN and M2CN catalysts, which enhancement may be due to the synergistic effect between Mn and Fe oxides, which can produce oxygen defects and structural distortion (Chen et al. 2019). Moreover, it should be noted that the addition of FeOx reduces the reduction temperature from 264 to 240 °C. However, the reduction temperature over M2CN obviously shifts to a higher temperature (305 °C) due to the excessive addition of Mn. Lower reduction temperature means a higher activity of oxygen vacancies, thus enhancing the reactivity of surface oxygen species (Jiang et al. 2020). Therefore, it is reasonable to deduce that the reactivity of oxygen vacancies increased in the following sequence: F-MCN > MCN > M2CN.

Fig. 4.

a H2-TPR, b O2-TPD profiles of MCN, M2CN, and F-MCN catalysts

The oxygen desorption behavior was investigated by O2-TPD, as presented in Fig. 4b. The peaks could be divided into three parts; i.e., below 300 °C was assigned to the desorption of physically adsorbed oxygen, the middle-temperature peak (350–600℃) is assigned to chemisorbed surface active oxygen, and the high-temperature peak (650–900℃) attributed to the desorption of lattice oxygen species (Gong et al. 2019b). Compared with MCN and M2CN, the catalyst modified with FeOx exhibits the most intensity at 200–600℃. Meanwhile, the peak intensity of M2CN is obviously less than that of MCN; it illustrates that excessive doping of Mn is unfavorable for the formation of oxygen vacancies (Zhang et al. 2020). The results indicated that between Fe and Mn, there exists a strong interaction, resulting in surface defects. Therefore, addition of Fe into MCN could enhance surface adsorbed oxygen content and surface lattice oxygen became more mobile, which is in good agreement with the XPS results. Previous studies have proven that the existence of abundant surface active oxygen species facilitates the destruction of VOC molecules, ozone molecules, and the deep oxidation of intermediates (Gong et al. 2019b). In comparison with MCN and M2CN catalysts, the F-MCN catalyst possesses rich chemisorbed surface-active oxygen species with higher reducibility, mobility, and reactivity due to the strong interaction between Fe and Mn. Therefore, the F-MCN catalyst has a great advantage in HCHO removal.

Thermo-catalytic activity

During the performance of as-synthesized catalysts for HCHO oxidation at different temperatures, the removal activity was investigated with the initial HCHO concentration of 15 ppm, total gas flow rate of 1200 sccm, and GHSV of 15,000 h−1, as shown in Fig. 5. CO was not detected in our experimental condition. For all three catalysts evaluated, it is observed that the HCHO conversion is less than 50% as the operating temperature is below 50 °C, and the HCHO conversion increases with increasing temperature rapidly above 50 °C. Complete conversions of HCHO over MCN and M2CN catalysts were achieved at 150 °C, while MCN exhibited a higher activity at low temperatures. Catalytic oxidation of HCHO over F-MCN exhibited 100% conversion at 100 °C, which is 50 °C lower than those of MCN and M2CN under HCHO complete conversion. Certainly, catalytic performance of F-MCN is better than that of MCN and M2CN, suggesting that addition of FeOx could enhance the catalytic conversion of HCHO. Besides, the results indicate there is also a striking improvement of catalytic HCHO conversion when a small amount of Mn is added into the catalysts; however, doping too much Mn may lead to the activity decrease.

Fig. 5.

HCHO conversion as a function of reaction temperature over MCN, M2CN, and F-MCN catalysts, respectively

Catalytic degradation of HCHO was obeyed by the Mars van Krevelen model, and the apparent activation energy (Ea) could be calculated by Eq. (2),

| 2 |

where R is the molar gas constant; T is the temperature at reaction; and A is the pre-exponential factor.

The Arrhenius plots for HCHO conversion of less than 20% over the as-synthetized catalysts are shown in Fig. S5. Under thermo-catalytic conditions, the correlation coefficients of MCN, M2CN, and F-MCN catalysts calculated by linear regression equations are 0.996, 0.991, and 0.990, respectively, showing that the experimental results meet the assumptions. Meanwhile, the calculated activation energies of MCN, M2CN, and F-MCN catalysts for HCHO oxidation are 33 kJ/mol, 34 kJ/mol, and 29 kJ/mol, respectively. The results illustrate that the Ea values for the F-MCN catalysts are reduced with the addition of FeOx, while the M2CN catalyst showed the highest Ea value. Meanwhile, as shown in Table S1, compared with other non-noble metal catalysts, F-MCN shows a reasonable Ea value, which was close to that of noble metal catalysts. In order to better evaluate the impact of modification on catalysts, we introduced the concept of the specific reaction rate (rcat (mol/(g·s)) which was defined as the moles of HCHO being converted per second per gram of catalyst (Du et al. 2018). The rcat was used to evaluate the intrinsic activity of a catalyst. Based on the activity data, we calculated the specific reaction rates (rcat) of three catalysts for HCHO oxidation. The results show that the specific reaction rates of F-MCN, M2CN, and MCN are 3.33 × 10 −6, 1.47 × 10 −6, and 2.07 × 10 −6 mol/(g·s), respectively. In addition, we can use the molar amount of the Mn (active metal) to determine the TOFMn. The results show that the TOFMn of F-MCN, M2CN, and MCN are 2.85, 2.57, and 2.77 × 10 −2 s −1, respectively. The results confirm that modification of FeOx is the main reason for improving the degradation efficiency of HCHO after excluding the effect of specific surface area.

Ozone catalytic oxidation activity

Three catalysts were investigated to compare their performance for HCHO oxidation with [O3]/[ HCHO] ratio = 4. As shown in Fig. 6(a), the HCHO oxidation efficiency decreased in the following order: F-MCN > MCN > M2CN. Nearly 88% of the HCHO was degraded over F-MCN, while the HCHO conversion rates achieved with MCN and M2CN reached 70% and 65%, respectively. Notably, no CO was detected in the exhaust gas of three catalysts, while CO2 was the major C-species. Previous studies indicate that decomposition of O3 was the first step for the ozone catalytic oxidation process, so the outlet O3 concentration was monitored [15,27]. Under dry conditions, it is exhibited that all three catalysts show excellent performance and complete decomposition of O3 is achieved and maintained within the 8-h test duration.

Fig. 6.

Catalytic performance of HCHO over as-synthesized catalysts with [O3]/[HCHO] = 4. Conditions: HCHO,15 ppm; total flow rate, 1,200 sccm; O3, 60 ppm; GHSV,15,000 h−1; temperature, 25 °C. a Dry air; b RH = 70%

In the real environment, however, there exists a significant amount of water vapor which may inhibit the catalytic activity; therefore, the test was carried out with RH = 70% to explore the humidity effect, as shown in Fig. 6b. The results indicate that F-MCN and MCN exhibit significant O3 decomposition rate, illustrating good humidity resistance. The efficiency of HCHO conversion achieved with F-MCN is up to 100%. Obviously, the rate of HCHO conversion to CO2 achieved with F-MCN catalyst increases along with the presence of water vapor. The abundant oxygen vacancies are very efficient active sites to enhance the water vapor decomposition to surface hydroxyl groups and assist the regeneration of catalyst.

However, ozone conversion rate decreased sharply to nearly 60% over M2CN, and HCHO mineralization rate further decreases to 40%, which emphasizes that O3 decomposition rate which is the first step for OZCO process. According to the results of catalyst characterization, the excessive Mn content blocks the surface pores to inhibit oxygen vacancies. Besides, excessive moisture may hinder the exposure of active sites, resulting in competitive adsorption of water molecules under the surface of catalyst, reducing the efficiency of ozone decomposition. It causes the reduction of the surface oxygen species (e.g., O•, •O2−) from ozone decomposition, which is not beneficial for HCHO oxidation. For better analyzing the mechanism of catalyst deactivation, the unit water content (U) to estimate the competitive adsorption can be calculated by the following formulas:

| 3 |

where W is the water content in the airflow and S is the SBET of catalyst. The unit water content value of F-MCN, MCN, and M2CN can be approximately calculated to be 0.1, 0.17, and 0.2 g/m2, respectively. The results show that competitive adsorption occurs when the weight of water on the catalyst is greater than 0.2 g per m2. It is noteworthy that after being treated with FeOx, the humidity resistance is enhanced and excellent HCHO and O3 conversion rates are simultaneously achieved.

For a better understanding of the kinetics of catalytic process, the degradation data of HCHO could be fitted with the pseudo-first-order kinetics, based on Eq. (4).

| 4 |

where t is the time of reaction, C0 and Ct were the HCHO concentrations at time 0 and t, and kαpp is the apparent first-order rate constant (min−1). As shown in Fig. S6, the calculated k value of F-MCN is 2.12*10–1 min−1 which is significantly higher than that of MCN and M2CN. The high decomposition efficiency and rate constant of F-MCN revealed the addition of FeOx promotes its superior reactivity, i.e., the active oxygen species, as manifested from the previous characterization. Furthermore, the poor activity of M2CN adequately suggested that the catalytic performance was highly dependent on its morphological structure, physical, and chemical properties.

In order to explore the OZCO performance of F-MCN with different O3/HCHO ratios, experimental tests were carried out at 15 ppm HCHO, ozone concentration varying from 30 to 60 ppm, and RH = 70% condition, with the results being shown in Fig. 7. As the [O3]/[HCHO] ratio is controlled at 4, F-MCN catalyst reveals excellent conversion for HCHO and maintains a 100% during the 8-h test period. When [O3]/[HCHO] ratio is reduced to 3, the conversion rate of HCHO decreases slightly, but still remains at 95%. As the [O3]/[HCHO] ratio is dropped to 2, although the catalyst does not show deactivation after 8 h of reaction, the efficiency gradually decreases to 65%. In summary, in the OZCO test with F-MCN, the catalyst exhibits excellent catalytic activity; when [O3]/[HCHO] ratio is reduced to 3, it still maintains a high conversion rate of HCHO (average of 95%). In the absence of a catalyst, no significant product was observed in the reactor even in the presence of ozone, implying that the ozone catalytic oxidation of formaldehyde was triggered by the F-MCN catalyst.

Fig. 7.

Catalytic performance of HCHO over F-MCN with different [O3]/[HCHO] ratios Conditions: HCHO,15 ppm; total flow rate, 1,200 sccm; O3, 30–60 ppm; GHSV, 15,000 h−1; RH = 70% at room temperature (25 °C)

Reusability of the F-MCN catalyst

Catalytic recycling of F-MCN

Stability is an important factor in judging the potential value of the catalyst in application. Regarding the stability of catalyst, the HCHO concentration of 15-ppm at [O3]/[HCHO] = 4 with MCN and F-MCN as catalyst for 6 h and the average value of each test was taken from three experimental runs. As shown in Fig. 8, after 3 cycles, the final HCHO conversion achieved with MCN was significantly decreased to 73%. However, F-MCN demonstrated an excellent stable HCHO conversion of 93% even after 3 cycles. Besides, deactivation and CO weren’t observed or detected for both catalysts. These data indicated that the F-MCN exhibited excellent durability to HCHO and ozone even under relatively long-term test. After modification with FeOx, the catalyst stability increases, and FeOx provides favorable corrosion resistance, credit to the strong interaction between the Fe and Mn (Wang et al. 2020b).

Fig. 8.

Stability test of MCN and F-MCN catalyst OZCO of HCHO. Conditions: HCHO,15 ppm; total flow rate, 1,200 sccm; O3, 60 ppm; GHSV, 15,000 h−1; RH = 70%

Figure S7 exhibited the XRD patterns of fresh and used F-MCN catalyst. After 3 cycles, the position and strength of peak were almost unchanged, which proved that after being modified by FeOx, the micromorphology of the catalyst has no obvious change during the OZCO tests, indicating that F-MCN had significant corrosion resistance and stability.

SBET analysis

To disclose the influence of carbon deposition on catalyst pores, the SBET analysis after OZCO reaction was conducted, as shown in Table 1. After reaction, the SBET of MCN decreased slightly from 119 to 113 m2/g, M2CN decreased from 70 to 59 m2/g, and F-MCN decreased slightly from 140 m2/g to 136 m2/g. In the reaction process, part of the intermediates and incomplete reaction products accumulated in the mesopores of the catalyst, resulting in the decrease of SBET. As for the pore size, MCN did not change significantly, while M2CN and F-MCN increased from 6.11 and 4.2 nm to 8.25 and 5.2 nm, respectively. That is generally ascribed to the carbon deposition on the catalyst which blocks some micropores (small holes), resulting in the increase of macropores proportion. Compared with MCN and M2CN catalysts, after modification with FeOx, SBET changes slightly, indicating less deposition of byproducts on catalyst. The results reveal that F-MCN has good resistance to endure the corrosion.

Thermogravimetry analysis

To compare the species changes and byproducts formation on catalyst surface after OZCO and thermal process, thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was investigated, and the profiles are presented in Fig. 9. For the fresh catalyst, almost 4.4% weight loss was observed for MCN catalyst, while this value was approximately 5.2% for M2CN catalyst. After modification with FeOx, the weight loss was reduced to 3.1%, suggesting better thermal stability. After OZCO and thermo-catalytic process, the weight losses of all catalysts were increased. Additionally, after thermo-catalytic processes, the weight loss is much higher than that of OZCO process for MCN and F-MCN catalysts. In general, a higher amount of byproduct was deposited on the catalyst when operated at room temperature, while the opposite trend was observed in this study. The results verified that the addition of O3 accelerated the conversion of formate to CO2 and reduced the formation and adsorption of intermediates and byproducts on catalyst surface. Besides, addition of O3 resulted in the formation of COx species, thereby enhanced CO and CO2 desorption (Chen et al. 2020a). However, M2CN catalyst could not utilize ozone completely and then reduces the conversion rate of formate to CO2 due to its weak O3 decomposition capacity. Then, the intermediates and byproduct are easy to accumulate on M2CN surface, and higher weight loss also proves this hypothesis. The above results also verify that catalytic decomposition of O3 is the first step for OZCO. In summary, the FeOx-MCN catalyst exhibits excellent thermostability and less byproduct deposition, suggesting a more stable structure is induced after MCN treated with FeOx.

Fig. 9.

Weight loss curves of the thermogravimetric analysis for a MCN, b M2CN, and c F-MCN under difference processes

Intermediates and mechanism

Under wet condition, F-MCN exhibited an excellent HCHO conversion rate, while M2CN HCHO mineralization rate sharply decreased. To shed light on HCHO ozone catalytic oxidation mechanism of F-MCN and catalyst deactivation mechanism over M2CN, the main intermediates formed were analyzed by in situ DRIFTS. The DRIFTS spectra over the M2CN and F-MCN catalysts under exposure to HCHO for 3 h were presented in Fig. 10a and b, respectively.

Fig.10.

In situ DRIFT spectra of HCHO interaction with ozone at room temperature under wet air conditions over a M2CN and b F-MCN samples as a function of time

The absorption bands at 1,360, 1,550, 1,650, and 3,249 cm−1 were observed on the catalysts. According to the previous studies, the characteristic peaks at 1,550 cm−1 were assigned to the asymmetric stretch [νas(COO −)] of formate species, and the weak bands at 1,360 cm−1 can be ascribed to monodentate carbonate species (Ji et al. 2020). The peaks of carbonate and formate species were hardly discriminated due to their co-existence within the wide wavenumber range of 1,300–1,500 cm−1 (Guo et al. 2019). Thus, it is speculated that the accumulation of carbonate and formate species factors is occurred.

As shown in Fig. 10a, excessive doping Mn ions results in fewer holes and oxygen vacancies, leading to the formate species and carbonate species accumulating on the surface of catalyst. Zhao et al. (2012) indicated that formate species, carbonate species, and other intermediate products are adsorbed and accumulated on the surface of catalysts which cannot be dissociated from the active sites, inducing the reduction of catalytic activity or even deactivation. Similarly, along with the reaction proceeds, the peak at 3,249 cm−1 gradually increased, which illustrates the water vapor formed during the OZCO process also accumulates on the catalyst surface. Chen et al. (2020b) demonstrated that the continuous formation of H2O results in competitive adsorption. The active sites of the catalyst were firmly occupied by them and could not be desorbed, which was also responsible for a reduction of the catalytic activity.

As presented in Fig. 10b, the intensity of formate and carbonate species on the surface of F-MCN catalyst remained almost unchanged during the reaction; the high reactivity of surface oxygen species enhanced HCHO promptly transformed, which indicated that the adsorption and desorption of formate species were in dynamic equilibrium. Meanwhile, the absorbance peak at 3,249 cm−1 displayed little change; the results illustrate that the surface hydroxyl groups were consumed during the reaction, which could be replenished during the reaction of HCHO and O3 under the surface of F-MCN. These results demonstrated that the enhancement of surface-active oxygen groups by FeOx modification could facilitate the intermediate species dissociation and further oxidize them to CO2 after the action of ozone. In summary, the desorption of both intermediates and products from F-MCN catalyst surface is much faster than that from M2CN. Based on the above analysis and previous studies (Zhao et al. 2012), the possible OZCO reaction mechanisms of HCHO over F-MCN catalyst were further proposed and demonstrated in Scheme 1.

Scheme 1.

Schematic illustration of the HCHO ozone catalytic oxidation over F-MCN

Process (A)

In this mechanism, O3 was initially adsorbed and activated via the catalyst; afterwards, O3 is decomposed by oxygen vacancy into the active oxygen radicals (O• and •O2−) (Wang et al. 2019). The C atoms of HCHO will be attacked by O• and •O2− under the surface of catalyst and generated to formate species. After that, formate species are further converted into carbonate species, which will quickly decompose into CO2 and H2O(g). Meanwhile, •O2− further reacts with ozone and releases the oxygen molecule from the catalyst surface to attain the reproduction of surface oxygen vacancy (Zhu et al. 2017b).

Process (B)

Under wet conditions, HCHO molecules firstly adsorb onto OH• groups by hydrogen bonding, while O3 molecules are adsorbed onto activated oxygen vacancy and decomposed into the active oxygen radicals (O•, •O2−) simultaneously. Afterwards, the surface oxygen species (e.g., O•, •O2−, OH•) oxidizes the HCHO adsorbed on the catalyst to unstable formate species. Finally, the •O2− further reacts with ozone, would release as the oxygen molecule from the surface to fill oxygen vacancies under the catalyst surface, and then CO2 and H2O(g) rapidly desorb from the catalyst surface.

Because of the existence of the surface OH group, there was almost negligible accumulation of carbonates species under the Process (B). Based on the investigation of the characteristics of catalysts before and after the reaction, it can be found that there is a slight deactivation and micropore blockage of the catalysts. Therefore, it is speculated that in the ozone catalytic oxidation over F-MCN, Process (B) is the predominant mechanism.

Conclusion

The MnCeNiOx (MCN) was prepared by the Pechini method and further treated with FeOx via impregnation method (F-MCN) and introduced into the OZCO system to discuss the effect of adding FeOx for the catalytic degradation of HCHO at room temperature. Under the dry condition, F-MCN catalyst exhibited better performance of HCHO conversion and ozone decomposition than MCN and M2CN catalysts due to abundant Mn3+ and Ce3+ which were proportional to the intensity of oxygen vacancies and surface adsorbed oxygen and large SBET. The excellent redox property is resulted from to the strong interaction between Mn-Ce, Ce-Ni, and Fe–Mn mixed crystal. Besides, under the wet system, the addition of water vapor enhanced the surface hydroxyl radicals, leading to the complete oxidation of HCHO over F-MCN catalyst under room temperature. Hydroxyl radical is regenerated from the interaction between adsorbed water molecules and surface oxygen species produced from the decomposition of ozone on the catalyst surface. This process is effective for the simultaneous decomposition of HCHO and O3 in indoor air due to water vapor always existing in the real environment. However, additional of water vapor inhibited the decomposition of ozone with M2CN and then reduces the decomposition of HCHO, which confirms that O3 catalytic destruction is the first step for OZCO. In addition, after 72-h continuous operation tests, the F-MCN catalyst exhibits excellent stability, and the crystal phase was almost unchanged, indicating FeOx provides a favorable corrosion resistance. Therefore, F-MCN catalyst revealed high HCHO and ozone removal performance in high RH conditions, demonstrating its great potential for practical applications.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contribution

RY Liu provided and analyzed the test data and wrote the manuscript. MM Trinh and HT Chuang helped revise the manuscript. MB Chang provided conceptual and technical guidance for all aspects of the project. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Bao W, et al. Pt nanoparticles supported on N/Ce-doped activated carbon for the catalytic oxidation of formaldehyde at room temperature. ACS Applied Nano Materials. 2020;3:2614–2624. doi: 10.1021/acsanm.0c00005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bariki R et al (2020) Facile synthesis and photocatalytic efficacy of UiO-66/CdIn2S4 nanocomposites with flowerlike 3D-microspheres towards aqueous phase decontamination of triclosan and H2 evolution. Appl Catal B :270

- Cao R et al (2019) Ammonium-treated birnessite-type MnO2 to increase oxygen vacancies and surface acidity for stably decomposing ozone in humid condition. Appl Surf Sci 495

- Chagas CA, et al. Copper as promoter of the NiO–CeO2 catalyst in the preferential CO oxidation. Appl Catal B. 2016;182:257–265. doi: 10.1016/j.apcatb.2015.09.033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chang T, et al. Post-plasma-catalytic removal of toluene using MnO2–Co3O4 catalysts and their synergistic mechanism. Chem Eng J. 2018;348:X15–25. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2018.04.186. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, et al. Low temperature selective catalytic reduction of NOx with NH3 over Fe–Mn mixed-oxide catalysts containing Fe3Mn3O8 phase. Ind Eng Chem Res. 2011;51:202–212. doi: 10.1021/ie201894c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B-b et al (2014) FeOx-supported gold catalysts for catalytic removal of formaldehyde at room temperature. Appl Catal B 154–155:73–81

- Chen S, et al. A novel highly active and sulfur resistant catalyst from Mn-Fe-Al layered double hydroxide for low temperature NH3-SCR. Catal Today. 2019;327:81–89. doi: 10.1016/j.cattod.2018.06.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G, et al. Comparative investigation on catalytic ozonation of VOCs in different types over supported MnOx catalysts. J Hazard Mater. 2020;391:122218–122235. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.122218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M, et al. Facet- and defect-engineered Pt/Fe2O3 nanocomposite catalyst for catalytic oxidation of airborne formaldehyde under ambient conditions. J Hazard Mater. 2020;395:122628–122638. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.122628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniells S, et al. The mechanism of low-temperature CO oxidation with Au/Fe2O3 catalysts: a combined Mössbauer, FT-IR, and TAP reactor study. J Catal. 2005;230:52–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jcat.2004.11.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Du J, et al. Low-temperature abatement of toluene over Mn-Ce oxides catalysts synthesized by a modified hydrothermal approach. Appl Surf Sci. 2018;433:1025–1035. doi: 10.1016/j.apsusc.2017.10.116. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Du W, et al. Indoor air pollution was nonnegligible during COVID-19 lockdown. Aerosol and Air Quality Research. 2020;20:1851–1855. doi: 10.4209/aaqr.2020.06.0281. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fang S, et al. Insights into the thermo-photo catalytic production of hydrogen from water on a low-cost NiOx-loaded TiO2 catalyst. ACS Catal. 2019;9:5047–5056. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.9b01110. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gong S, et al. Heterostructured Ni/NiO nanocatalysts for ozone decomposition. ACS Applied Nano Materials. 2019;3:597–607. doi: 10.1021/acsanm.9b02143. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gong S, et al. Highly active and humidity resistive perovskite LaFeO3 based catalysts for efficient ozone decomposition. Appl Catal B. 2019;241:578–587. doi: 10.1016/j.apcatb.2018.09.041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guo J, et al. Review on noble metal-based catalysts for formaldehyde oxidation at room temperature. Appl Surf Sci. 2019;475:237–255. doi: 10.1016/j.apsusc.2018.12.238. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchings GJ, et al. Role of gold cations in the oxidation of carbon monoxide catalyzed by iron oxide-supported gold. J Catal. 2006;242:71–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jcat.2006.06.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ji J et al (2020) Potassium-modulated δ-MnO2 as robust catalysts for formaldehyde oxidation at room temperature. Appl Catal B Environ 260

- Jiang F, et al. Insights into the influence of CeO2 crystal facet on CO2 hydrogenation to methanol over Pd/CeO2 catalysts. ACS Catal. 2020;10:11493–11509. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.0c03324. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jung H, et al. Changes in acetaldehyde and formaldehyde contents in foods depending on the typical home cooking methods. J Hazard Mater. 2021;414:125475–125482. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.125475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, et al. Oxygen vacancies induced by transition metal doping in gamma-MnO2 for highly efficient ozone decomposition. Environ Sci Technol. 2018;52:12685–12696. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.8b04294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, et al. Detrimental role of residual surface acid ions on ozone decomposition over Ce-modified gamma-MnO2 under humid conditions. J Environ Sci (china) 2020;91:43–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jes.2019.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lian Z, et al. Decomposition of high-level ozone under high humidity over Mn–Fe catalyst: the influence of iron precursors. Catal Commun. 2015;59:156–160. doi: 10.1016/j.catcom.2014.10.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, et al. Removing surface hydroxyl groups of Ce-modified MnO2 to significantly improve its stability for gaseous ozone decomposition. J Phys Chem C. 2017;121:23488–23497. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcc.7b07931. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F, et al. One-step synthesis of nanocarbon-decorated MnO2 with superior activity for indoor formaldehyde removal at room temperature. Appl Catal B. 2018;235:158–167. doi: 10.1016/j.apcatb.2018.04.078. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J et al (2020) Novel CeMnaOx catalyst for highly efficient catalytic decomposition of ozone. Appl Catal B Environ 264

- Nielsen GD, et al. Re-evaluation of the WHO (2010) formaldehyde indoor air quality guideline for cancer risk assessment. Arch Toxicol. 2017;91:35–61. doi: 10.1007/s00204-016-1733-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song S, et al. Heterostructured Ni/NiO composite as a robust catalyst for the hydrogenation of levulinic acid to γ-valerolactone. Appl Catal B. 2017;217:115–124. doi: 10.1016/j.apcatb.2017.05.073. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, et al. Role of oxygen vacancies and Mn sites in hierarchical Mn2O3/LaMnO3-δ perovskite composites for aqueous organic pollutants decontamination. Appl Catal B. 2019;245:546–554. doi: 10.1016/j.apcatb.2019.01.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, et al. Highly efficient WO3-FeOx catalysts synthesized using a novel solvent-free method for NH3-SCR. J Hazard Mater. 2020;388:121812. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2019.121812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q et al (2018) Ultrathin two-dimensional BiOBrxI1-x solid solution with rich oxygen vacancies for enhanced visible-light-driven photoactivity in environmental remediation. 236:222–232

- Wang Y et al (2020b) Study on the structure-activity relationship of Fe-Mn oxide catalysts for chlorobenzene catalytic combustion. Chem Eng J 395

- Ye J et al (2022) Hierarchical Co3O4-NiO hollow dodecahedron-supported Pt for room-temperature catalytic formaldehyde decomposition. Chem Eng J 430

- Zhang M, et al. Catalytic oxidation of NO with O2 over FeMnOx/TiO2: effect of iron and manganese oxides loading sequences and the catalytic mechanism study. Appl Surf Sci. 2014;300:58–65. doi: 10.1016/j.apsusc.2014.02.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, et al. Simultaneously catalytic decomposition of formaldehyde and ozone over manganese cerium oxides at room temperature: promotional effect of relative humidity on the MnCeOx solid solution. Catal Today. 2019;327:323–333. doi: 10.1016/j.cattod.2018.04.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C, et al. LaMnO3 perovskites via a facile nickel substitution strategy for boosting propane combustion performance. Ceram Int. 2020;46:6652–6662. doi: 10.1016/j.ceramint.2019.11.153. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao D, et al. Enhanced effect of water vapor on complete oxidation of formaldehyde in air with ozone over MnOx catalysts at room temperature. J Hazard Mater. 2012;239–240:362–369. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2012.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu B, et al. A novel process of ozone catalytic oxidation for low concentration formaldehyde removal. Chin J Catal. 2017;38:1759–1769. doi: 10.1016/S1872-2067(17)62890-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu G, et al. Surface oxygen vacancy induced α-MnO2 nanofiber for highly efficient ozone elimination. Appl Catal B. 2017;209:729–737. doi: 10.1016/j.apcatb.2017.02.068. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.