Abstract

This study aimed to quantify the association between exposure to pandemic outbreaks and psychological health via a comprehensive meta-analysis. Literature retrieval, study selection, and data extraction were completed independently and in duplicate. Effect-size estimates were expressed as odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval (CI). Data from 22 articles, involving 40,900 persons, were meta-analyzed. Overall analyses revealed a significant association of exposing to SARS-CoV–related pandemics with human mental health (OR, 1.32; 95% CI, 1.24–1.40; p < 0.001). Subgroup analyses showed that anxiety (OR, 1.37; 95% CI, 1.19–1.58; p < 0.001), depression (OR, 1.28; 95% CI, 1.15–1.42; p < 0.001), posttraumatic stress (OR, 1.36; 95% CI, 1.17–1.58; p < 0.001), and psychological distress (OR, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.11–1.40; p < 0.001) were all obviously related to pandemic diseases. In the context of infectious disease outbreaks, the mental health of general populations is clearly vulnerable. Therefore, all of us, especially health care workers, need special attention and psychological counseling to overcome pandemic together.

Key Words: COVID-19, SARS, pandemic, mental health, psychological distress

Growing epidemiologic data have demonstrated that pandemics can cause a broad spectrum of issues involving both physical and mental health in human beings (Holmes et al., 2020; Norris et al., 2002). In particular, pandemics, such as severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in 2003, influenza virus with the H1N1 subtype in 2009, Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) in 2012, Ebola virus in 2014, and coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), during the past two decades are highly contagious and have caused heavy public health burdens regionally and globally (Fisman and Laupland, 2009; Klenk, 2014; Lam et al., 2004; Li et al., 2020b). More recently, the terrible COVID-19 have caused 42,055,863 confirmed cases, including 1,141,567 deaths as of October 24, 2020, and these numbers keep rising at an alarming rate. An equally serious problem is the profound consequence on spiritual damage to mankind, as researchers have proposed that patients who survived severe and life-threatening illnesses are at an enhanced risk of experiencing mental disorder. Factors such as long duration of quarantine, fears for infection, inadequate information, stigma, or financial loss were found to be more or less related to negative psychological impact (Brooks et al., 2020). In 2003, SARS outbreak had caused 50% of recovered patients who remained anxious and 29% of health care workers who experienced probable emotional distress (Nickell et al., 2004; Tsang et al., 2004). As demonstrated in the recent meta-analysis by Krishnamoorthy and colleagues, COVID-19 pandemic raised stress disorder by 40%, anxiety by 30%, burnout by 28%, depression by 24%, and posttraumatic stress disorder by 13% (Krishnamoorthy et al., 2020). Yet, the magnitude of the association between pandemic and mental disorder is still an open question, due to the sustainable skyrocketed growth of confirmed cases and death for COVID-19. Meanwhile, the pooled prevalence rate of psychological morbidities could not intuitively represent the association between the outbreak of pandemic and mental health.

To quantify the association between exposure to pandemic outbreaks and psychological health, we synthesized the results of cross-section studies in medical literature through a comprehensive meta-analysis.

METHODS

The performance of meta-analysis adhered to the guidelines in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) statement (Page et al., 2021). The PRISMA checklist is presented in Supplementary Table 1 (Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/JNMD/A147).

This study is a meta-analysis on published studies, and so ethical approval and informed consent are not needed.

Search Strategy

Literature search was conducted by scanning PubMed, EMBASE, and Web of Science databases as of August 4, 2020. The following medical topic terms are used: (obsession compulsion*) OR (depression) OR (depressive symptom*) OR (anxiety disorder*) OR (neurotic anxiety state) OR (hostility) OR (phobic disorder) OR (phobic*) OR (paranoid disorder) OR (paranoi*) OR (suicide*) OR (mental health*) OR (mental*) OR (psychiatric disorder) OR (psychiatric*) OR (psycho*) [Title/Abstract] AND (Acute Respiratory Syndrome Virus*) OR (SARS-Related*) OR (SARS-CoV) OR (Urbani SARS-Associated Coronavirus) OR (Influenza in Bird) OR (Avian Flu*) OR (H1N1 Virus*) OR (Swine-Origin Influenza A H1N1 Virus) OR (novel coronavirus vaccine) OR (coronavirus disease 2019 vaccine*) OR (2019 novel coronavirus vaccine) OR (SARS 2 vaccine*) OR (Wuhan coronavirus vaccine) OR (Zika*) OR (Middle East Respiratory Syndrome*) [Title/Abstract].

The reference lists of major retrieved articles were also manually searched to avoid potential missing hits.

Search process was independently conducted by two investigators (X.D. and M.H.) using the same medical topic terms. All references retrieved were combined, and duplicates were removed.

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

Our analysis was restricted to articles that met the following criteria: (1) study participants, aged ≥18 years old; (2) end points, related mental disorder; (3) study design, cross-sectional or cohort studies; (4) baseline exposure, different kinds of exposure to pandemic diseases; and (5) odds ratio (OR) as effect-size estimate. Articles were excluded if they involved study participants with serious diseases or if they are case reports or case series, editorials, and narrative reviews.

Data Extraction

Two investigators (M.H. and X.D.) independently extracted data from each qualified article, including first author, year of publication, country where study was conducted, sample size, sex, baseline age, study type, the type of exposed infectious disease, the method of assessing mental health, the type of psychological-related questionnaire, effect estimation, and severity of exposure to pandemic diseases, if available. The divergence was resolved through joint reevaluation of original articles, and if necessary, by a third author (W.N.).

Quality Assessment

The quality of all eligible studies was assessed using the 11-item checklist, which was recommended by Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) (Rostom et al., 2004). The item would be scored “0” if the answer was “no” or “unclear,” whereas “1” represented the answer “yes.” Article quality was assessed to three different grades: low quality (0–3); moderate quality (4–7); and high quality (8–11). Differences in article quality were discussed to reach a final agreement.

Statistical Analyses

Data management and analysis were handled using the STATA software version 14.1 for Windows (Stata Corp, College Station, TX). Effect-size estimates were expressed as OR with 95% confidence interval (CI). Pooled effect-size estimates were derived under the random-effects Mantel-Haenszel model, irrespective of the magnitude of between-study heterogeneity.

The inconsistency index (I2), which represents the percent of diversity that is due to heterogeneity rather than chance, is used to quantify between-study heterogeneity. The I2 greater than 50% denotes significant heterogeneity, and a higher percentage indicates a higher degree of heterogeneity. To account for possible sources of between-study heterogeneity from clinical and methodological aspects, a large number of prespecified subgroup analyses were done according to major exposure subjects, the level of development of the countries, the different pandemic diseases, and the different kinds of exposure respectively.

The probability of publication bias was evaluated by both Begg's funnel plots and Egger's regression asymmetry tests at a significance level of 10%. The trim-and-fill method was used to estimate the number of theoretically missing studies.

RESULTS

Eligible Studies

After searching prespecified public databases using predefined medical subject terms, a total of 1073 articles were initially identified, and 22 of them were qualified for analysis, including 40,900 study participants (Abdessater et al., 2020; Cao et al., 2020; Chan and Huak, 2004; Choi et al., 2020; Gómez-Salgado et al., 2020; Gualano et al., 2020; Guo et al., 2020; Huang and Zhao, 2020; Lai et al., 2020; Leung et al., 2005; Li et al., 2020a; Lu et al., 2020; Peng et al., 2010; Rossi et al., 2020; Shacham et al., 2020; Sim et al., 2004; Tam et al., 2004; Verma et al., 2004; Wu et al., 2009; Xiao et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2020; Ying et al., 2020). The detailed selection process is schematized in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Flowchart of records retrieved, screened, and included in this meta-analysis.

Study Characteristics

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of studies that respectively recorded OR in this meta-analysis. Because of the lack of data on other pandemics, the present analysis was only restricted to SARS and COVID-19.

TABLE 1.

The Baseline Characteristics of All Involved Studies in This Meta-analysis

| First Author | Year | Country | Gender | Age, y | Exposure Subjects | Sample Size | Study Type | Infectious Disease | Method | Type of Questionnaire | Assessment of Different Kinds of Exposures | Mental Disorder | Effect Size | 95% LL | 95% UL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chan | 2004 | Singapore | All | >18 | Health care workers | 661 | Cross-section study | SARS | Questionnaire | GHQ | Direct contact with suspected patients | Psychological distress | 1.60 | 1.10 | 2.50 |

| Chan | 2004 | Singapore | All | >18 | Health care workers | 661 | Cross-section study | SARS | Questionnaire | GHQ | Direct contact with suspected patients | Psychological distress | 1.40 | 1.02 | 2.00 |

| Tam | 2004 | China | All | 33 | Health care workers | 652 | Cross-section study | SARS | Questionnaire | GHQ | Direct contact with suspected patients | Psychological distress | 1.00 | 0.73 | 1.38 |

| Verma | 2004 | Singapore | All | >18 | Health care workers | 721 | Cross-section study | SARS | Questionnaire | GHQ | Direct contact with suspected patients | Psychological distress | 2.90 | 1.30 | 6.30 |

| Sim | 2004 | Singapore | All | >18 | Health care workers | 277 | Cross-section study | SARS | Questionnaire | GHQ | Direct contact with suspected patients | Psychological distress | 0.82 | 0.39 | 1.72 |

| Sim | 2004 | Singapore | All | >18 | Health care workers | 277 | Cross-section study | SARS | Questionnaire | GHQ | Direct contact with suspected patients | Psychological distress | 0.51 | 0.17 | 1.50 |

| Leung | 2005 | China | All | >18 | General population | 480 | Longitudinal study | SARS | Random-digit dialing | STAI | Exposed to epidemics | Anxiety | 2.63 | 1.43 | 4.84 |

| Leung | 2005 | China | All | >18 | General population | 480 | Longitudinal study | SARS | Random-digit dialing | STAI | Exposed to epidemics | Anxiety | 2.95 | 1.56 | 5.60 |

| Leung | 2005 | China | All | >18 | General population | 272 | Longitudinal study | SARS | Random-digit dialing | STAI | Exposed to epidemics | Anxiety | 0.87 | 0.42 | 1.81 |

| Leung | 2005 | China | All | >18 | General population | 272 | Longitudinal study | SARS | Random-digit dialing | STAI | Exposed to epidemics | Anxiety | 1.04 | 0.43 | 2.51 |

| Wu | 2009 | China | All | >18 | Health care workers | 549 | Cross-section study | SARS | Questionnaire | IES-R | Exposed to epidemics | Posttraumatic stress | 3.47 | 1.90 | 6.20 |

| Wu | 2009 | China | All | >18 | Health care workers | 549 | Cross-section study | SARS | Questionnaire | IES-R | Relatives or friends infected | Posttraumatic stress | 3.74 | 1.80 | 7.60 |

| Peng | 2010 | China | All | ≥18 | Health care workers | 1278 | Cross-section study | SARS | Random-digit dialing | BSRS | Perceived epidemics as serious | Psychological distress | 1.27 | 0.54 | 2.98 |

| Cao | 2020 | China | All | ≥18 | Students | 7143 | Cross-section study | COVID-19 | Questionnaire | GAD | Relatives or friends infected | Anxiety | 3.01 | 2.38 | 3.80 |

| Choi | 2020 | China | All | ≥18 | General population | 500 | Cross-section study | COVID-19 | Questionnaire | PHQ | Perceived epidemics as serious | Depression | 1.86 | 1.37 | 2.52 |

| Choi | 2020 | China | All | ≥18 | General population | 500 | Cross-section study | COVID-19 | Questionnaire | GAD | Perceived epidemics as serious | Anxiety | 1.73 | 1.25 | 2.40 |

| Gualano | 2020 | Italy | All | ≥18 | General population | 1515 | Cross-section study | COVID-19 | Questionnaire | PHQ | Direct contact with suspected patients | Depression | 0.99 | 0.73 | 1.34 |

| Gualano | 2020 | Italy | All | ≥18 | General population | 1515 | Cross-section study | COVID-19 | Questionnaire | GAD | Direct contact with suspected patients | Anxiety | 1.41 | 1.04 | 1.89 |

| Gómez-Salgado | 2020 | Spain | All | ≥18 | General population | 4180 | Cross-section study | COVID-19 | Questionnaire | GHQ | Direct contact with suspected patients | Psychological distress | 1.24 | 1.03 | 1.50 |

| Gómez-Salgado | 2020 | Spain | All | ≥18 | General population | 4180 | Cross-section study | COVID-19 | Questionnaire | GHQ | Direct contact with suspected patients | Psychological distress | 1.20 | 0.98 | 1.46 |

| Gómez-Salgado | 2020 | Spain | All | ≥18 | General population | 4180 | Cross-section study | COVID-19 | Questionnaire | GHQ | Direct contact with suspected patients | Psychological distress | 1.26 | 1.05 | 1.50 |

| Gómez-Salgado | 2020 | Spain | All | ≥18 | General population | 4180 | Cross-section study | COVID-19 | Questionnaire | GHQ | Relatives or friends infected | Psychological distress | 1.08 | 0.88 | 1.32 |

| Gómez-Salgado | 2020 | Spain | All | ≥18 | General population | 4180 | Cross-section study | COVID-19 | Questionnaire | GHQ | Relatives or friends infected | Psychological distress | 1.11 | 0.69 | 1.80 |

| Guo | 2020 | China | All | ≥18 | General population | 2441 | Cross-section study | COVID-19 | Questionnaire | PTSD | Direct contact with suspected patients | Posttraumatic stress | 1.21 | 0.92 | 1.60 |

| Guo | 2020 | China | All | ≥18 | General population | 2441 | Cross-section study | COVID-19 | Questionnaire | PTSD | Direct contact with suspected patients | Depression | 1.39 | 1.08 | 1.80 |

| Huang | 2020 | China | All | ≥18 | General population | 7236 | Cross-section study | COVID-19 | Online survey | GAD | Direct contact with suspected patients | Anxiety | 1.30 | 0.82 | 2.08 |

| Huang | 2020 | China | All | ≥18 | General population | 7236 | Cross-section study | COVID-19 | Online survey | CES-D | Direct contact with suspected patients | Depression | 1.02 | 0.58 | 1.81 |

| Huang | 2020 | China | All | ≥18 | General population | 7236 | Cross-section study | COVID-19 | Online survey | GAD | Perceived epidemics as serious | Anxiety | 0.80 | 0.38 | 1.69 |

| Huang | 2020 | China | All | ≥18 | General population | 7236 | Cross-section study | COVID-19 | Online survey | CES-D | Perceived epidemics as serious | Depression | 1.12 | 0.42 | 3.02 |

| Lai | 2020 | China | All | 26–40 | Health care workers | 1257 | Cross-section study | COVID-19 | Questionnaire | PHQ | Direct contact with suspected patients | Depression | 1.52 | 1.11 | 2.09 |

| Lai | 2020 | China | All | 26–40 | Health care workers | 1257 | Cross-section study | COVID-19 | Questionnaire | GAD | Direct contact with suspected patients | Anxiety | 1.57 | 1.22 | 2.02 |

| Lai | 2020 | China | All | 26–40 | Health care workers | 1257 | Cross-section study | COVID-19 | Questionnaire | IES-R | Direct contact with suspected patients | Psychological distress | 1.60 | 1.25 | 2.04 |

| Li | 2020 | China | Female | ≥19 | Health care workers | 5317 | Cross-section study | COVID-19 | Questionnaire | PHQ | Relatives or friends infected | Depression | 1.39 | 1.16 | 1.66 |

| Li | 2020 | China | Female | ≥19 | Health care workers | 5317 | Cross-section study | COVID-19 | Questionnaire | GAD | Relatives or friends infected | Anxiety | 1.32 | 0.94 | 1.87 |

| Lu | 2020 | China | All | ≥18 | Health care workers | 2299 | Cross-section study | COVID-19 | Questionnaire | NRS | Direct contact with suspected patients | Fear | 1.30 | 0.99 | 1.73 |

| Lu | 2020 | China | All | ≥18 | Health care workers | 2299 | Cross-section study | COVID-19 | Questionnaire | NRS | Direct contact with suspected patients | Fear | 1.41 | 1.03 | 1.93 |

| Lu | 2020 | China | All | ≥18 | Health care workers | 2299 | Cross-section study | COVID-19 | Questionnaire | HAMA | Direct contact with suspected patients | Anxiety | 1.31 | 0.89 | 1.92 |

| Lu | 2020 | China | All | ≥18 | Health care workers | 2299 | Cross-section study | COVID-19 | Questionnaire | HAMA | Direct contact with suspected patients | Anxiety | 2.06 | 1.35 | 3.15 |

| Lu | 2020 | China | All | ≥18 | Health care workers | 2299 | Cross-section study | COVID-19 | Questionnaire | HAMD | Direct contact with suspected patients | Depression | 1.39 | 0.80 | 2.43 |

| Lu | 2020 | China | All | ≥18 | Health care workers | 2299 | Cross-section study | COVID-19 | Questionnaire | HAMD | Direct contact with suspected patients | Depression | 2.02 | 1.10 | 3.69 |

| Xiao | 2020 | China | All | ≥17 | Students | 933 | Cross-section study | COVID-19 | Questionnaire | GAD | Perceived epidemics as serious | Anxiety | 1.07 | 0.90 | 1.27 |

| Xiao | 2020 | China | All | ≥17 | Students | 933 | Cross-section study | COVID-19 | Questionnaire | GAD | Perceived epidemics as serious | Anxiety | 1.01 | 0.90 | 1.13 |

| Rossi | 2020 | Italy | All | >18 | Health care workers | 1379 | Cross-section study | COVID-19 | Questionnaire | GPS-PTSD | Direct contact with suspected patients | Posttraumatic stress | 1.37 | 1.05 | 1.80 |

| Rossi | 2020 | Italy | All | >18 | Health care workers | 1379 | Cross-section study | COVID-19 | Questionnaire | PHQ | Direct contact with suspected patients | Depression | 1.04 | 0.76 | 1.42 |

| Rossi | 2020 | Italy | All | >18 | Health care workers | 1379 | Cross-section study | COVID-19 | Questionnaire | GAD | Direct contact with suspected patients | Anxiety | 1.13 | 0.80 | 1.59 |

| Rossi | 2020 | Italy | All | >18 | Health care workers | 1379 | Cross-section study | COVID-19 | Questionnaire | PSS | Direct contact with suspected patients | Posttraumatic stress | 1.16 | 0.84 | 1.60 |

| Rossi | 2020 | Italy | All | >18 | Health care workers | 1379 | Cross-section study | COVID-19 | Questionnaire | GPS-PTSD | Direct contact with suspected patients | Posttraumatic stress | 1.12 | 0.81 | 1.55 |

| Rossi | 2020 | Italy | All | >18 | Health care workers | 1379 | Cross-section study | COVID-19 | Questionnaire | PHQ | Direct contact with suspected patients | Depression | 1.36 | 0.95 | 1.96 |

| Rossi | 2020 | Italy | All | >18 | Health care workers | 1379 | Cross-section study | COVID-19 | Questionnaire | GAD | Direct contact with suspected patients | Anxiety | 1.09 | 0.74 | 1.61 |

| Rossi | 2020 | Italy | All | >18 | Health care workers | 1379 | Cross-section study | COVID-19 | Questionnaire | PSS | Direct contact with suspected patients | Posttraumatic stress | 0.74 | 0.51 | 1.08 |

| Rossi | 2020 | Italy | All | >18 | Health care workers | 1379 | Cross-section study | COVID-19 | Questionnaire | GPS-PTSD | Direct contact with suspected patients | Posttraumatic stress | 1.20 | 0.86 | 1.67 |

| Rossi | 2020 | Italy | All | >18 | Health care workers | 1379 | Cross-section study | COVID-19 | Questionnaire | PHQ | Direct contact with suspected patients | Depression | 0.71 | 0.48 | 1.05 |

| Rossi | 2020 | Italy | All | >18 | Health care workers | 1379 | Cross-section study | COVID-19 | Questionnaire | GAD | Direct contact with suspected patients | Anxiety | 0.96 | 0.64 | 1.44 |

| Rossi | 2020 | Italy | All | >18 | Health care workers | 1379 | Cross-section study | COVID-19 | Questionnaire | PSS | Direct contact with suspected patients | Posttraumatic stress | 0.75 | 0.51 | 1.11 |

| Rossi | 2020 | Italy | All | >18 | Health care workers | 1379 | Cross-section study | COVID-19 | Questionnaire | GPS-PTSD | Direct contact with suspected patients | Posttraumatic stress | 1.75 | 1.03 | 2.97 |

| Rossi | 2020 | Italy | All | >18 | Health care workers | 1379 | Cross-section study | COVID-19 | Questionnaire | PHQ | Direct contact with suspected patients | Depression | 0.98 | 0.53 | 1.82 |

| Rossi | 2020 | Italy | All | >18 | Health care workers | 1379 | Cross-section study | COVID-19 | Questionnaire | GAD | Direct contact with suspected patients | Anxiety | 1.05 | 0.53 | 2.08 |

| Rossi | 2020 | Italy | All | >18 | Health care workers | 1379 | Cross-section study | COVID-19 | Questionnaire | PSS | Direct contact with suspected patients | Posttraumatic stress | 1.18 | 0.66 | 2.11 |

| Rossi | 2020 | Italy | All | >18 | Health care workers | 1379 | Cross-section study | COVID-19 | Questionnaire | GPS-PTSD | Direct contact with suspected patients | Posttraumatic stress | 1.54 | 1.10 | 2.16 |

| Rossi | 2020 | Italy | All | >18 | Health care workers | 1379 | Cross-section study | COVID-19 | Questionnaire | PHQ | Direct contact with suspected patients | Depression | 1.39 | 0.95 | 2.03 |

| Rossi | 2020 | Italy | All | >18 | Health care workers | 1379 | Cross-section study | COVID-19 | Questionnaire | GAD | Direct contact with suspected patients | Anxiety | 1.18 | 0.78 | 1.77 |

| Rossi | 2020 | Italy | All | >18 | Health care workers | 1379 | Cross-section study | COVID-19 | Questionnaire | PSS | Direct contact with suspected patients | Posttraumatic stress | 1.93 | 1.30 | 2.85 |

| Rossi | 2020 | Italy | All | >18 | Health care workers | 1379 | Cross-section study | COVID-19 | Questionnaire | GPS-PTSD | Direct contact with suspected patients | Posttraumatic stress | 1.59 | 1.21 | 2.09 |

| Rossi | 2020 | Italy | All | >18 | Health care workers | 1379 | Cross-section study | COVID-19 | Questionnaire | PHQ | Direct contact with suspected patients | Depression | 1.38 | 1.00 | 1.90 |

| Rossi | 2020 | Italy | All | >18 | Health care workers | 1379 | Cross-section study | COVID-19 | Questionnaire | GAD | Direct contact with suspected patients | Anxiety | 1.19 | 0.85 | 1.67 |

| Rossi | 2020 | Italy | All | >18 | Health care workers | 1379 | Cross-section study | COVID-19 | Questionnaire | PSS | Direct contact with suspected patients | Posttraumatic stress | 1.66 | 1.19 | 2.32 |

| Rossi | 2020 | Italy | All | >18 | Health care workers | 1379 | Cross-section study | COVID-19 | Questionnaire | GPS-PTSD | Direct contact with suspected patients | Posttraumatic stress | 1.23 | 0.93 | 1.62 |

| Rossi | 2020 | Italy | All | >18 | Health care workers | 1379 | Cross-section study | COVID-19 | Questionnaire | PHQ | Direct contact with suspected patients | Depression | 1.54 | 1.11 | 2.14 |

| Rossi | 2020 | Italy | All | >18 | Health care workers | 1379 | Cross-section study | COVID-19 | Questionnaire | GAD | Direct contact with suspected patients | Anxiety | 1.14 | 0.81 | 1.62 |

| Rossi | 2020 | Italy | All | >18 | Health care workers | 1379 | Cross-section study | COVID-19 | Questionnaire | PSS | Direct contact with suspected patients | Posttraumatic stress | 1.01 | 0.73 | 1.41 |

| Shacham | 2020 | Israel | All | 24–74 | Health care workers | 338 | Cross-section study | COVID-19 | Online survey | K6 | Direct contact with suspected patients | Psychological distress | 0.91 | 0.64 | 1.28 |

| Shacham | 2020 | Israel | All | 24–74 | Health care workers | 338 | Cross-section study | COVID-19 | Online survey | K6 | Direct contact with suspected patients | Psychological distress | 2.11 | 1.24 | 3.60 |

| Abdessater | 2020 | French | All | 29.5 | Health care workers | 275 | Cross-section study | COVID-19 | Questionnaire | GHQ | Direct contact with suspected patients | Posttraumatic stress | 1.85 | 0.98 | 3.59 |

| Yang | 2020 | South Korea | All | 20–50 | Health care workers | 65 | Cross-section study | COVID-19 | Questionnaire | PHQ | Relatives or friends infected | Depression | 1.52 | 0.26 | 20.90 |

| Yang | 2020 | South Korea | All | 20–50 | Health care workers | 65 | Cross-section study | COVID-19 | Questionnaire | GAD | Relatives or friends infected | Anxiety | 0.68 | 0.12 | 9.19 |

| Ying | 2020 | China | All | 37 | General population | 285 | Cross-section study | COVID-19 | Questionnaire | PHQ | Direct contact with suspected patients | Depression | 1.04 | 0.77 | 1.42 |

| Ying | 2020 | China | All | 37 | General population | 406 | Cross-section study | COVID-19 | Questionnaire | GAD | Direct contact with suspected patients | Anxiety | 1.41 | 1.05 | 1.89 |

| Ying | 2020 | China | All | 37 | General population | 47 | Cross-section study | COVID-19 | Questionnaire | PHQ | Relatives or friends infected | Depression | 1.20 | 0.68 | 2.07 |

| Ying | 2020 | China | All | 37 | General population | 70 | Cross-section study | COVID-19 | Questionnaire | GAD | Relatives or friends infected | Anxiety | 1.43 | 0.84 | 2.42 |

| Ying | 2020 | China | All | 37 | General population | 112 | Cross-section study | COVID-19 | Questionnaire | PHQ | Perceived epidemics as serious | Depression | 0.89 | 0.51 | 1.52 |

| Ying | 2020 | China | All | 37 | General population | 112 | Cross-section study | COVID-19 | Questionnaire | GAD | Perceived epidemics as serious | Anxiety | 1.15 | 0.68 | 1.94 |

| Ying | 2020 | China | All | 37 | General population | 212 | Cross-section study | COVID-19 | Questionnaire | PHQ | Perceived epidemics as serious | Depression | 1.54 | 1.01 | 2.35 |

| Ying | 2020 | China | All | 37 | General population | 212 | Cross-section study | COVID-19 | Questionnaire | GAD | Perceived epidemics as serious | Anxiety | 1.95 | 1.28 | 2.96 |

LL, lower limit; UL, upper limit; GHQ, General Health Questionnaire; PHQ, Patient Health Questionnaire; GAD, Generalized Anxiety Disorder scale; STAI, State Trait Anxiety Inventory; PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder; IES-R, Impact of Event Scale–Revised; BSRS, five-item Brief Symptom Rating Scale; NRS, Numeric Rating Scale; HAMA, Hamilton Anxiety Scale; HAMD, Hamilton Depression Scale; GPS, Global Psychotrauma Scale; PSS, Perceived Stress Scale; K6, Kessler's K6.

Of 22 eligible articles, eight looked at the relationship between pandemic disease and psychological distress (Chan and Huak, 2004; Gómez-Salgado et al., 2020; Lai et al., 2020; Peng et al., 2010; Shacham et al., 2020; Sim et al., 2004; Tam et al., 2004; Verma et al., 2004), 11 articles related to anxiety (Cao et al., 2020; Choi et al., 2020; Gualano et al., 2020; Huang and Zhao, 2020; Lai et al., 2020; Leung et al., 2005; Li et al., 2020a; Lu et al., 2020; Rossi et al., 2020; Xiao et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2020), nine involved in depression (Choi et al., 2020; Gualano et al., 2020; Guo et al., 2020; Huang and Zhao, 2020; Lai et al., 2020; Li et al., 2020a; Lu et al., 2020; Rossi et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2020), and four studies connected to posttraumatic stress (Abdessater et al., 2020; Guo et al., 2020; Rossi et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2009). In terms of study subjects, 14 concerned the mental health of the health care workers (Abdessater et al., 2020; Chan and Huak, 2004; Gualano et al., 2020; Lai et al., 2020; Li et al., 2020a; Lu et al., 2020; Peng et al., 2010; Rossi et al., 2020; Shacham et al., 2020; Sim et al., 2004; Tam et al., 2004; Verma et al., 2004; Wu et al., 2009; Yang et al., 2020), six adopted general population (Choi et al., 2020; Gómez-Salgado et al., 2020; Guo et al., 2020; Huang and Zhao, 2020; Leung et al., 2005; Ying et al., 2020), and two pointed to college students (Cao et al., 2020; Xiao et al., 2020). Meanwhile, seven studies assessed SARS (Chan and Huak, 2004; Leung et al., 2005; Peng et al., 2010; Sim et al., 2004; Tam et al., 2004; Verma et al., 2004; Wu et al., 2009), and the other 15 regarded COVID-19 (Abdessater et al., 2020; Cao et al., 2020; Choi et al., 2020; Gómez-Salgado et al., 2020; Gualano et al., 2020; Guo et al., 2020; Huang and Zhao, 2020; Lai et al., 2020; Li et al., 2020a; Lu et al., 2020; Rossi et al., 2020; Shacham et al., 2020; Xiao et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2020; Ying et al., 2020). On the basis of different countries, all studies were divided into developed countries (Abdessater et al., 2020; Chan and Huak, 2004; Gómez-Salgado et al., 2020; Gualano et al., 2020; Rossi et al., 2020; Shacham et al., 2020; Sim et al., 2004; Verma et al., 2004; Yang et al., 2020) and developing countries (Cao et al., 2020; Choi et al., 2020; Guo et al., 2020; Huang and Zhao, 2020; Lai et al., 2020; Leung et al., 2005; Li et al., 2020a; Lu et al., 2020; Peng et al., 2010; Tam et al., 2004; Wu et al., 2009; Xiao et al., 2020; Ying et al., 2020). Assessment tools used in the studies were various questionnaires; more details were presented in Table 1. As to the assessment of different kinds of exposures, we excluded the diverse ways of expression from the initial studies and concluded them to similar expression of unity. For example, we treated “worried about being infected by COVID-19” and “concerns about the COVID-19 pandemic,” “time to think about COVID-19 per day (hours) (2–3 hours),” and “time to think about COVID-19 per day (hours) (>3 hours)” as “perceived pandemic as serious,” and viewed the expressions such as “working frontline,” “high-risk contact,” and “low-risk contact” in health care workers as “direct contact with suspect or probable patients.” All of the different kinds of exposures were seen as the psychological impact of the pandemic.

Quality Assessment

Table 2 shows the quality assessment of all eligible articles by using the AHRQ cross-sectional study evaluation criteria. The average total score was 5.55 (range, 3 to 8).

TABLE 2.

AHRQ Cross-Sectional Study Evaluation Criteria

| Year | First Author | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 | Chan | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| 2004 | Sim | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 5 |

| 2004 | Tam | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 5 |

| 2004 | Verma | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 7 |

| 2005 | Leung | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| 2009 | Wu | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| 2010 | Peng | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 8 |

| 2020 | Abdessater | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 5 |

| 2020 | Cao | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 5 |

| 2020 | Choi | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 7 |

| 2020 | Gómez-Salgado | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 7 |

| 2020 | Gualano | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 7 |

| 2020 | Guo | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 8 |

| 2020 | Huang | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 7 |

| 2020 | Lai | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 6 |

| 2020 | Li | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 5 |

| 2020 | Lu | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 6 |

| 2020 | Rossi | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 7 |

| 2020 | Shacham | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| 2020 | Xiao | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 5 |

| 2020 | Yang, S | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| 2020 | Yang, Y | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 7 |

Notes: 1) define the source of information (survey, record review); 2) list inclusion and exclusion criteria for exposed and unexposed subjects (cases and controls) or refer to previous publications; 3) indicate period used for identifying patients; 4) indicate whether or not subjects were consecutive if not population-based; 5) indicate if evaluators of subjective components of study were masked to other aspects of the status of the participants; 6) describe any assessments undertaken for quality assurance purposes (e.g., test/retest of primary outcome measurements); 7) explain any patient exclusions from analysis; 8) describe how confounding was assessed and/or controlled; 9) if applicable, explain how missing data were handled in the analysis; 10) summarize patient response rates and completeness of data collection; 11) clarify what follow-up, if any, was expected and the percentage of patients for which incomplete data or follow-up was obtained.

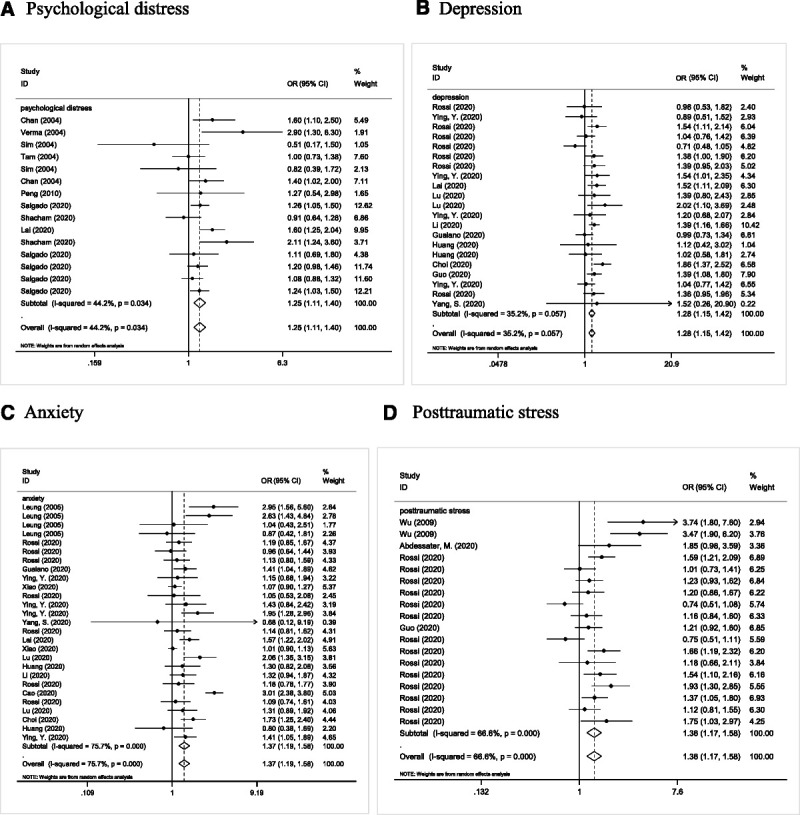

Overall Analyses

A statistically significant association of exposing to pandemic with humans' mental health was observed based on the overall analysis (OR, 1.32; 95% CI, 1.24–1.40; p < 0.001; I2, 62.0%) (Table 3), which was calculated by random-effects model (p < 0.05) with between-study heterogeneity. Four groups of mental disorders were analyzed separately, including anxiety (OR, 1.37; 95% CI, 1.19–1.58; p < 0.001; I2, 75.7%), depression (OR, 1.28; 95% CI, 1.15–1.42; p < 0.001; I2, 35.2%), posttraumatic stress (OR, 1.36; 95% CI, 1.17–1.58; p < 0.001; I2, 66.6%), and psychological distress (OR, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.11–1.40; p < 0.001; I2, 44.2%) (Fig. 2).

TABLE 3.

Overall and Subgroup Analyses on the Association of Exposure to Pandemics With Human Mental Health

| Group | No. Qualified Studies | All Types | Anxiety | Depression | Posttraumatic Stress | Psychological Distress | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI); P | I 2 | OR (95% CI); P | I 2 | OR (95% CI); P | I 2 | OR (95% CI); P | I 2 | OR (95% CI); P | I 2 | ||

| Overall analyses | |||||||||||

| Mental disorders | 83/27/21/18/15 | 1.32 (1.24–1.40); <0.001 | 62% | 1.37 (1.19–1.58); <0.001 | 75.7% | 1.28 (1.15–1.42); <0.001 | 35.2% | 1.36 (1.17–1.58); <0.001 | 66.6% | 1.25 (1.11–1.40); <0.001 | 44.2% |

| Subgroup analyses | |||||||||||

| By source of participants | |||||||||||

| General population | 27/12/9/*/15 | 1.30 (1.19–1.42); <0.001 | 36.0% | 1.50 (1.26–1.78); <0.001 | 35.5% | 1.24 (1.04–1.48); 0.017 | 42.1% | 1.21 (0.92–1.60); 0.177 | * | 1.20 (1.09–1.31); <0.001 | 0.0% |

| Health care workers | 53/12/12/7/10 | 1.31 (1.22–1.41); <0.001 | 48.9% | 1.27 (1.13–1.43); <0.001 | 7.7% | 1.30 (1.14–1.49); <0.001 | 34.6% | 1.38 (1.17–1.62); <0.001 | 68.4% | 1.32 (1.05–1.65); 0.019 | 59.1% |

| Students | 3/3/*/* | 1.47 (0.83–2.60); 0.186 | 97.1% | 1.47 (0.83–2.60); 0.186 | 97.1% | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| By country development | |||||||||||

| Developing countries | 38 | 1.46 (1.30–1.63); <0.001 | 73.3% | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| Developed countries | 45 | 1.22 (1.14–1.30); <0.001 | 36.2% | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| By type of pandemics | |||||||||||

| SARS | 13/4/*/2/7 | 1.61 (1.20–2.17); 0.002 | 69.9% | 1.70 (0.92–3.14); <0.091 | 66.9% | * | * | 3.58 (2.27–5.65); <0.001 | 0.0% | 1.26 (0.94–1.68); 0.118 | 49.7% |

| COVID-19 | 70/23/21/16/8 | 1.29 (1.21–1.38); <0.001 | 59.6% | 1.34 (1.16–1.54); <0.001 | 76.5% | 1.28 (1.15–1.42); <0.001 | 35.2% | 1.27 (1.11–1.44); <0.001 | 52.8% | 1.24 (1.10–1.40); 0.001 | 46.8% |

| By kinds of exposure | |||||||||||

| Direct contact with suspect patients | 57 | 1.27 (1.20–1.34); <0.001 | 37.1% | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| Exposed to epidemic | 5 | 1.99 (1.17–3.39); 0.012 | 67.7% | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| Relatives or friends infected | 10 | 1.54 (1.13–2.09); 0.006 | 83.4% | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * |

| Perceived epidemics as serious | 11 | 1.29 (1.07–1.56); 0.007 | 67.7% | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * |

*Data are unavailable.

FIGURE 2.

Forest plot presenting the association between the emerging outbreak of infection disease with common mental disorders among people in studies providing OR and 95% CI.

Cumulative and Influential Analyses

In cumulative analysis, the first two published studies by Sim and Tam made in 2004 concluded the pandemic as a protective factor for human' mental disorder; since then, other studies all got completely opposite conclusions consistently, and the trend tended to stabilize. The influential analyses revealed no significant impact of any single studies on overall effect-size estimates.

Publication Bias

Figure 3 shows the Begg's and filled funnel plots on the association of pandemic disease with mental health. The overall analysis of pandemic disease revealed that no publication bias relies on Egger's test (p = 0.14). Similarly, there were evidences of symmetry of study effects in terms of anxiety (p = 0.23), depression (p = 0.47), posttraumatic stress (p = 0.11), and psychological distress (p = 0.84).

FIGURE 3.

The Begg's and filled funnel plots of the association of pandemic disease with mental health.

Further investigation using the “trim-and-fill” method produced that there was one theoretically missing study aforementioned required for a further test of symmetry in overall analysis. Meanwhile, three missing studies were requested for both comparisons to make the Begg's funnel plots symmetrical in posttraumatic stress. After adjusting, the ORs for influencing mental health and getting posttraumatic stress were 1.31 (95% CI, 1.23–1.40; p < 0.001) and 1.24 (95% CI, 1.05–1.46; p = 0.01), respectively. Concerning the group of having anxiety, depression, and psychological distress, they did not produce any correction to the original estimates.

Subgroup Analyses

Between-study heterogeneity existed in the overall analysis for exposing to pandemic associated with human's mental disorder (I2 = 62.0%). A series of prespecified subgroup analysis were done to explore possible sources of between-study heterogeneity (Table 3). By major exposure subjects, in general population, there was a remarkably significant association of exposing to pandemic with mental disorder (OR, 1.30; 95% CI, 1.19–1.42; p < 0.001), including anxiety (OR, 1.50; 95% CI, 1.26–1.78; p < 0.001), depression (OR, 1.24; 95% CI, 1.04–1.48; p = 0.017), posttraumatic stress (OR, 1.21; 95% CI, 0.92–1.60; p = 0.177), and psychological distress (OR, 1.20; 95% CI, 1.09–1.31; p < 0.001). In health care workers, synthetic analysis demonstrated the risk magnitude, and the OR was 1.31 (95% CI, 1.22–1.41; p < 0.001), containing anxiety (OR, 1.27; 95% CI, 1.13–1.43; p < 0.001), depression (OR, 1.30; 95% CI, 1.14–1.49; p < 0.001), posttraumatic stress (OR, 1.38; 95% CI, 1.17–1.62; p < 0.001), and psychological distress (OR, 1.32; 95% CI, 1.05–1.65; p = 0.019). At the same time, no detectable significance was observed in students, although the OR was 1.47 (95% CI, 0.83–2.60; p = 0.186).

By different levels of development, developing countries were illustrated to have a high risk of experiencing mental disorder (OR, 1.46; 95% CI, 1.30–1.63; p < 0.001), and developed countries satisfied this relationship as well (OR, 1.22; 95% CI, 1.14–1.30; p < 0.001).

In terms of different infectious diseases, there was a remarkably significant association of SARS with mental disorder (OR, 1.61; 95% CI, 1.20–2.17; p = 0.002), and it was the same in COVID-19 (OR, 1.29; 95% CI, 1.21–1.38; p < 0.001).

With regard to different kinds of exposure, the OR of subjects who directly contacted with suspected patients was 1.27 (95% CI, 1.20–1.34; p < 0.001), that of those who were exposed to pandemic was 1.99 (95% CI, 1.17–3.39; p = 0.012), and that of those whose relatives or friends were infected was 1.54 (95% CI, 1.13–2.09; p = 0.006). Meanwhile, those who perceived a pandemic as serious also experienced high risk of mental disorder (OR, 1.29; 95% CI, 1.07–1.56; p = 0.007).

DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, this is thus far the most comprehensive meta-analysis that has explored the relationship between pandemic exposure and mental disorder by using the OR as the analytical indicator. Our key findings indicated that people who experienced a pandemic could increase approximately 1.32 times the risk of having psychological problems, including 1.37 times the risk of getting anxiety, 1.28 times the risk of getting depression, 1.36 times the risk of having posttraumatic stress, and 1.25 times the risk of having psychological distress. Moreover, our subsidiary analyses demonstrated that different major exposure subjects, countries' level of development, infectious disease, and kinds of exposure were possible sources of between-study heterogeneity. Comprehensive evaluation made by our study focused on the magnitude of the outbreak of pandemic, and we found the related risk factors including contacted with suspect patients directly, exposed to the pandemic, whose relatives or friends infected, and perceived pandemic as serious. We highlighted the importance and the necessity for a sustained, efficient mental health care delivery along with a pandemic.

Pandemics, with filled unpredictability and uncertainty, had posed numerous and unprecedented challenges and threats worldwide during each outbreak. Although much of the early scholarly work had focused on intensive, emergency, and primary care, a long time of searching precautionary measures had proposed that the role of mental health clinicians was key on multiple levels. A recent review concluded that negative psychological effects caused by pandemic were widespread and stressors were also diversified, including longer quarantine duration, infection fears, frustration, boredom, inadequate supplies, inadequate information, financial loss, and stigma (Brooks et al., 2020). Simultaneously, evidence showed that these maladaptive reactions can be long-lasting, as the study illustrated that mental disorder, such as posttraumatic and depressive symptoms, and general psychological distress were reported after periods ranging from 6 months up to 3 years after the pandemic outbreak (Liu et al., 2012; Maunder et al., 2006). Long-term behavioral changes such as vigilant handwashing and avoidance of crowds were described in a qualitative study among general population; for some, the return to normality was delayed by many months (Cava et al., 2005). The same is true of health care workers. Researchers found that alcohol abuse or dependency symptoms were positively related to quarantined health care workers even 3 years after the SARS outbreak (Wu et al., 2008).

In this sense, public health should not only increase mental health literacy but provide clear and concise information about infection rates and risk of infection to reduce uncertainty. Our meta-analysis was based on researches involved in people at high or low risk of exposure to a pandemic, with such OR to describe the risk of getting mental disorder, not relied on the prevalence of stress, anxiety, and depression in the general population after the pandemic. We got the statistically significant association of exposing to pandemic with humans' mental health, especially for health care workers. Studies investigated the possible work-related features connected to mental health outcomes, including working in high-risk units, contacting affected patients directly, being quarantined, having relatives or friends get infected, sharper at disease-related risk perception (Preti et al., 2020). These were consistent with our causal analysis.

There were several limitations in this study. First of all, this meta-analysis only included SARS and COVID-19; influenza caused by the virus subtype H1N1, MERS, and Ebola virus disease were not concluded, which limited the representativeness of this study. Second, the degree of exposures was ranked from least to most in the original articles, with different assessments of exposures; the present secondary analysis could not avoid the fuzzy definition of control groups. Meanwhile, all of the studies in our analysis were cross-section studies, which could reflect the psychological state of the population over a period. Hence, more studies on account of a longer and more forward-looking period observation can be helpful in further identification of mental health status.

CONCLUSIONS

In the context of infectious disease outbreaks, the mental health of general populations is clearly vulnerable. Both the general population and health care workers all experienced a high risk of developing mental health problems. Therefore, all of us need urgent attention and psychological counseling to overcome pandemic together.

DISCLOSURE

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval and consent to participate were received by each involved study in this meta-analysis.

The data sets used and/or analyzed during the current meta-analysis are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

All authors read and approved the final manuscript before submission. W.N. and Z.Z. conceived and designed the experiments. X.D., J.H., and M.H. performed the experiments. X.D., M.H., J.Z., and W.N. analyzed the data. X.D., M.H., J.Z., M.L., and Z.Z. contributed the materials/analysis tools. X.D. and W.N. wrote the article.

X.D., M.H., and J.Z. shared first authors.

Footnotes

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s Web site (www.jonmd.com).

Contributor Information

Xiangling Deng, Email: dengxiangling_zryh@163.com.

Mengyang He, Email: 1160448286@qq.com.

Jinhe Zhang, Email: 306158762@qq.com.

Jinchang Huang, Email: zryhhuang@163.com.

Minjing Luo, Email: lmj13051539932@163.com.

Zhixin Zhang, Email: zhangzhixin032@163.com.

REFERENCES

- Abdessater M, Rouprêt M, Misrai V, Matillon X, Gondran-Tellier B, Freton L, Vallée M, Dominique I, Felber M, Khene ZE, Fortier E, Lannes F, Michiels C, Grevez T, Szabla N, Boustany J, Bardet F, Kaulanjan K, Seizilles de Mazancourt E, Ploussard G, Pinar U, Pradere B. (2020) COVID19 pandemic impacts on anxiety of French urologist in training: Outcomes from a national survey. Prog Urol. 30:448–455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, Woodland L, Wessely S, Greenberg N, Rubin GJ. (2020) The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 395:912–920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao W, Fang Z, Hou G, Han M, Xu X, Dong J, Zheng J. (2020) The psychological impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on college students in China. Psychiatry Res. 287:112934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cava MA, Fay KE, Beanlands HJ, McCay EA, Wignall R. (2005) The experience of quarantine for individuals affected by SARS in Toronto. Public Health Nurs. 22:398–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan AO, Huak CY. (2004) Psychological impact of the 2003 severe acute respiratory syndrome outbreak on health care workers in a medium size regional general hospital in Singapore. Occup Med (Lond). 54:190–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi EPH, Hui BPH, Wan EYF. (2020) Depression and anxiety in Hong Kong during COVID-19. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 17:3740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisman DN, Laupland KB. (2009) Influenza mixes its pitches: Lessons learned to date from the influenza a (H1N1) pandemic. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 20:89–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Salgado J, Andres-Villas M, Dominguez-Salas S, Diaz-Milanes D, Ruiz-Frutos C. (2020) Related health factors of psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic in Spain. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 17:3947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gualano MR, Lo Moro G, Voglino G, Bert F, Siliquini R. (2020) Effects of Covid-19 lockdown on mental health and sleep disturbances in Italy. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 17:4779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo J, Feng XL, Wang XH, van IMH (2020) Coping with COVID-19: Exposure to COVID-19 and negative impact on livelihood predict elevated mental health problems in Chinese adults. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 17:3857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes EA, O'Connor RC, Perry VH, Tracey I, Wessely S, Arseneault L, Ballard C, Christensen H, Cohen Silver R, Everall I, Ford T, John A, Kabir T, King K, Madan I, Michie S, Przybylski AK, Shafran R, Sweeney A, Worthman CM, Yardley L, Cowan K, Cope C, Hotopf M, Bullmore E. (2020) Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: A call for action for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatry. 7:547–560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y, Zhao N. (2020) Generalized anxiety disorder, depressive symptoms and sleep quality during COVID-19 outbreak in China: A web-based cross-sectional survey. Psychiatry Res. 288:112954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klenk HD. (2014) Lessons to be learned from the ebolavirus outbreak in West Africa. Emerg Microbes Infect. 3:e61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnamoorthy Y, Nagarajan R, Saya GK, Menon V. (2020) Prevalence of psychological morbidities among general population, healthcare workers and COVID-19 patients amidst the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 293:113382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai J, Ma S, Wang Y, Cai Z, Hu J, Wei N, Wu J, Du H, Chen T, Li R, Tan H, Kang L, Yao L, Huang M, Wang H, Wang G, Liu Z, Hu S. (2020) Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open. 3:e203976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam CW, Chan MH, Wong CK. (2004) Severe acute respiratory syndrome: Clinical and laboratory manifestations. Clin Biochem Rev. 25:121–132. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung GM, Ho LM, Chan SK, Ho SY, Bacon-Shone J, Choy RY, Hedley AJ, Lam TH, Fielding R. (2005) Longitudinal assessment of community psychobehavioral responses during and after the 2003 outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Hong Kong. Clin Infect Dis. 40:1713–1720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G, Miao J, Wang H, Xu S, Sun W, Fan Y, Zhang C, Zhu S, Zhu Z, Wang W. (2020a) Psychological impact on women health workers involved in COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan: A cross-sectional study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 91:895–897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Guan X, Wu P, Wang X, Zhou L, Tong Y, Ren R, Leung KSM, Lau EHY, Wong JY, Xing X, Xiang N, Wu Y, Li C, Chen Q, Li D, Liu T, Zhao J, Liu M, Tu W, Chen C, Jin L, Yang R, Wang Q, Zhou S, Wang R, Liu H, Luo Y, Liu Y, Shao G, Li H, Tao Z, Yang Y, Deng Z, Liu B, Ma Z, Zhang Y, Shi G, Lam TTY, Wu JT, Gao GF, Cowling BJ, Yang B, Leung GM, Feng Z. (2020b) Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 382:1199–1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Kakade M, Fuller CJ, Fan B, Fang Y, Kong J, Guan Z, Wu P. (2012) Depression after exposure to stressful events: Lessons learned from the severe acute respiratory syndrome epidemic. Compr Psychiatry. 53:15–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu W, Wang H, Lin Y, Li L. (2020) Psychological status of medical workforce during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study. Psychiatry Res. 288:112936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maunder RG, Lancee WJ, Balderson KE, Bennett JP, Borgundvaag B, Evans S, Fernandes CM, Goldbloom DS, Gupta M, Hunter JJ, McGillis Hall L, Nagle LM, Pain C, Peczeniuk SS, Raymond G, Read N, Rourke SB, Steinberg RJ, Stewart TE, VanDeVelde-Coke S, Veldhorst GG, Wasylenki DA. (2006) Long-term psychological and occupational effects of providing hospital healthcare during SARS outbreak. Emerg Infect Dis. 12:1924–1932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickell LA, Crighton EJ, Tracy CS, Al-Enazy H, Bolaji Y, Hanjrah S, Hussain A, Makhlouf S, Upshur RE. (2004) Psychosocial effects of SARS on hospital staff: Survey of a large tertiary care institution. CMAJ. 170:793–798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris FH, Friedman MJ, Watson PJ, Byrne CM, Diaz E, Kaniasty K. (2002) 60,000 disaster victims speak: Part I. An empirical review of the empirical literature, 1981–2001. Psychiatry. 65:207–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hrobjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, McGuinness LA, Stewart LA, Thomas J, Tricco AC, Welch VA, Whiting P, Moher D. (2021) The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 372:n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng EY, Lee MB, Tsai ST, Yang CC, Morisky DE, Tsai LT, Weng YL, Lyu SY. (2010) Population-based post-crisis psychological distress: An example from the SARS outbreak in Taiwan. J Formos Med Assoc. 109:524–532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preti E, Di Mattei V, Perego G, Ferrari F, Mazzetti M, Taranto P, Di Pierro R, Madeddu F, Calati R. (2020) The psychological impact of epidemic and pandemic outbreaks on healthcare workers: Rapid review of the evidence. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 22:43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi R, Socci V, Pacitti F, Di Lorenzo G, Di Marco A, Siracusano A, Rossi A. (2020) Mental health outcomes among frontline and second-line health care workers during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic in Italy. JAMA Netw Open. 3:e2010185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rostom A, Dubé C, Cranney A, Saloojee N, Sy R, Garritty C, Sampson M, Zhang L, Yazdi F, Mamaladze V, Pan I, McNeil J, Moher D, Mack D, Patel D. (2004) Celiac disease. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US) Evidence Reports/Technology Assessments, No. 104. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK35149/. Accessed September 15, 2020. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shacham M, Hamama-Raz Y, Kolerman R, Mijiritsky O, Ben-Ezra M, Mijiritsky E. (2020) COVID-19 factors and psychological factors associated with elevated psychological distress among dentists and dental hygienists in Israel. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 17:2900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sim K, Chong PN, Chan YH, Soon WS. (2004) Severe acute respiratory syndrome-related psychiatric and posttraumatic morbidities and coping responses in medical staff within a primary health care setting in Singapore. J Clin Psychiatry. 65:1120–1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tam CW, Pang EP, Lam LC, Chiu HF. (2004) Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in Hong Kong in 2003: Stress and psychological impact among frontline healthcare workers. Psychol Med. 34:1197–1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsang HW, Scudds RJ, Chan EY. (2004) Psychosocial impact of SARS. Emerg Infect Dis. 10:1326–1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma S, Mythily S, Chan YH, Deslypere JP, Teo EK, Chong SA. (2004) Post-SARS psychological morbidity and stigma among general practitioners and traditional Chinese medicine practitioners in Singapore. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 33:743–748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu P, Fang Y, Guan Z, Fan B, Kong J, Yao Z, Liu X, Fuller CJ, Susser E, Lu J, Hoven CW. (2009) The psychological impact of the SARS epidemic on hospital employees in China: Exposure, risk perception, and altruistic acceptance of risk. Can J Psychiatry. 54:302–311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu P, Liu X, Fang Y, Fan B, Fuller CJ, Guan Z, Yao Z, Kong J, Lu J, Litvak IJ. (2008) Alcohol abuse/dependence symptoms among hospital employees exposed to a SARS outbreak. Alcohol Alcoholism (Oxford, Oxfordshire). 43:706–712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao H, Shu W, Li M, Li Z, Tao F, Wu X, Yu Y, Meng H, Vermund SH, Hu Y. (2020) Social distancing among medical students during the 2019 coronavirus disease pandemic in China: Disease awareness, anxiety disorder, depression, and behavioral activities. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 17:5047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang S, Kwak SG, Ko EJ, Chang MC. (2020) The mental health burden of the COVID-19 pandemic on physical therapists. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 17:3723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ying Y, Ruan L, Kong F, Zhu B, Ji Y, Lou Z. (2020) Mental health status among family members of health care workers in Ningbo, China, during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak: A cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry. 20:379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]