Abstract

We report the oxidative addition of phenylsilane to the complete series of alkali metal (AM) aluminyls [AM{Al(NONDipp)}]2 (AM = Li, Na, K, Rb, and Cs). Crystalline products (1-AM) have been isolated as ether or THF adducts, [AM(L)n][Al(NONDipp)(H)(SiH2Ph)] (AM = Li, Na, K, Rb, L = Et2O, n = 1; AM = Cs, L = THF, n = 2). Further to this series, the novel rubidium rubidiate, [{Rb(THF)4}2(Rb{Al(NONDipp)(H)(SiH2Ph)}2)]+ [Rb{Al(NONDipp)(H)(SiH2Ph)}2]−, was isolated during an attempted recrystallization of Rb[Al(NONDipp)(H)(SiH2Ph)] from a hexane/THF mixture. Structural and spectroscopic characterizations of the series 1-AM confirm the presence of μ-hydrides that bridge the aluminum and alkali metals (AM), with multiple stabilizing AM···π(arene) interactions to either the Dipp- or Ph-substituents. These products form a complete series of soluble, alkali metal (hydrido) aluminates that present a platform for further reactivity studies.

Short abstract

Oxidative addition of phenylsilane to alkali metal (AM) aluminyls affords a full series of (silyl)(hydrido) aluminates for AM = Li, Na, K, Rb, and Cs, with an increased tendency for AM···π(arene) for the larger AM cations.

Introduction

Since the isolation of the first stable molecular Al(I) complex in 1981,1 low-valent aluminum chemistry has been established as a fertile area of main group chemistry research.2 Early work largely focused on neutral species, with the chemistry of Al(BDIDipp) (BDIDipp = [HC{C(Me)NDipp}2]−, Dipp = 2,6-iPr2C6H3)3 and [Cp*Al]41 dominating the area. Among the myriad of reactions that have been established with these species, the activation of chemical bonds via an oxidative addition to afford Al(III) derivatives has featured prominently.4

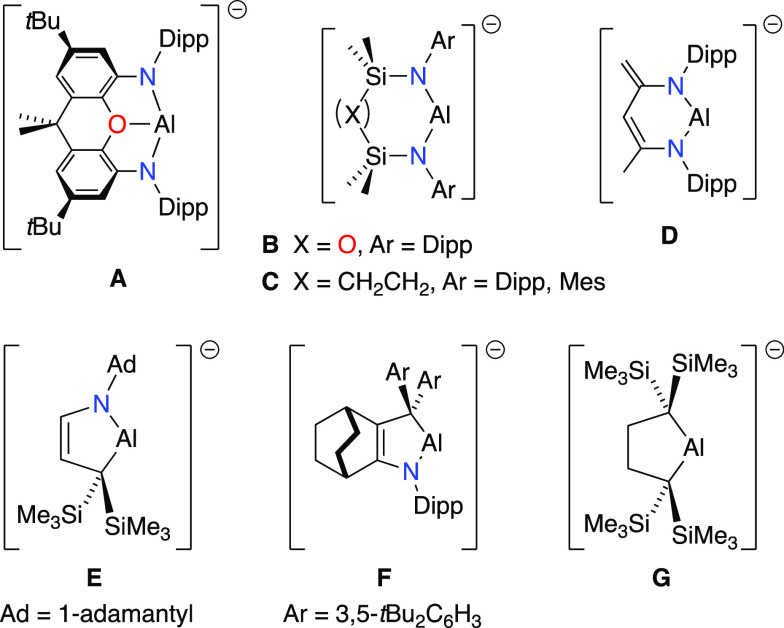

In 2018, a new class of anionic Al(I) complex entered the scene,5 prompting a surge in interest in this field.6 The initially reported compound consisted of a three-coordinate aluminum center supported by a diamido ligand set built around the xanthene scaffold [xanthNONDipp]2– (A), with a potassium cation to balance the charge.5 This report was rapidly followed by examples of two-coordinate diamido-(B-D),7 alkyl-amido-(E,F),8 and dialkyl-(G)9 aluminyl anions, all of which were isolated as their potassium salts (Figure 1). These compounds are able to activate strong and otherwise inert bonds in small molecule substrates, including H2,5,10 CO2,11 and CO.12

Figure 1.

Current family of alkali metal aluminyl anions. A = [Al(xanthNONDipp)]−, where xanthNONDipp = [4,5-(DippN)2-2,7-tBu2-9,9-Me2-xanthene]2– and Dipp = 2,6-iPr2C6H3; B = [Al(NONDipp)], where NONDipp = [O(SiMe2NDipp)2]2–; C = [Al(CH2SiMe2NAr)2]−, where Ar = Dipp, Mes; D = [Al(BDI-H)]−, where BDI-H = [DippNC(Me)=C(H)C(=CH2)NDipp]2–; E = [Al(AdN(CH)2C{SiMe3}2)]−, where Ad = 1-adamantyl; F = [Al(DippN{CCH(CH2)CH2}2CAr2)]−, where {CCH(CH2)CH2}2 = a substituted bicyclo[2.2.2]oct-2-ene group and Ar = 3,5-tBu2C6H3; G = [Al(CH2C{SiMe3}2)2]−.

The concept of alkali metal mediation (AMM) has been presented to highlight the often underappreciated role of group 1 metals in enabling reactions often involving bimetallic systems, in which an alkali metal (AM) is partnered with a metal from the p- or d-block of the periodic table.13 It recognizes cooperative/synergistic interactions between the AM and other metallic elements, without which a specific chemical transformation may not occur (or may not proceed efficiently).14 The partnership between the alkali metal cation and the aluminum center of the aluminyl anion lends itself to the possibility of AMM during reactivity and offers an opportunity to examine the role of AM in this emerging area of chemistry. Despite this potential, aluminyl chemistry research has to date focused almost exclusively on potassium complexes, precluding the chance to study AMM in these systems. The synthesis of aluminyl compounds with a series of AM cations and the ability to control the nature and extent of the AM···Al interactions will be key to understanding the aluminyl chemistry and unlocking the potential of these systems.

It has recently been noted that it is not possible to access the [Al(xanthNONDipp)]− anion via reduction of the iodide precursor using Li or Na metal, leading instead to either decomposition (AM = Li) or formation of the Al(II) dimer (AM = Na).15 An alternative route to the lithium–aluminyl complex (xanthNONDipp)Al–Li(Et2O)2 has been presented via metathesis of potassium aluminyl with lithium iodide, although this highly reactive product could only be isolated in low yield. These factors have thus far prevented systematic studies concerning the influence that the AM has on the chemical reactivity of [Al(xanthNONDipp)]− aluminyl. In contrast, we have reported the reduction of (NONDipp)Al–I (H), with both lithium and sodium metal proceeding smoothly to afford the corresponding lithium and sodium aluminyls, [AM{Al(NONDipp)}]2 (AM = Li, Na), that crystallize as slipped contacted dimeric pairs (CDPs) in which the aluminum engages in a single Al···AM interaction.10 Furthermore, the reaction of H with graphitic rubidium and cesium (RbC8 or CsC8)16 affords the corresponding heavier alkali metal aluminyls, [AM{Al(NONDipp)}]2 (AM = Rb, Cs).17 These compounds, together with the initially prepared potassium aluminyl,7a provide an opportunity to probe any AMM effects for the series of aluminyl anions incorporating the full complement of stable alkali metals, Li–Cs.

Harder and co-workers have recently expanded the series of aluminyls containing the [Al(BDI-H)]− ([BDI-H]2– = [DippNC(Me)=C(H)C(=CH2)NDipp]2–; DFigure 1) anion to encompass the full series [AM{Al(BDI-H)}]2 (AM = Li–Cs).18 Analogous to our results, the lithium and sodium derivatives have been isolated as the slipped CDPs and can be easily converted into the corresponding monomeric ion pairs (MIPs), (BDI-H)Al–Li(Et2O)2, and (BDI-H)Al–Na(Et2O) (TMEDA), when exposed to coordinating solvents. However, a difference is observed between the crystal structures of Rb and Cs within each series. We had noted previously that the monomeric units in [AM{Al(NONDipp)}]2 (AM = Rb, Cs) CDPs were twisted relative to one another, rationalized as a requirement for the accommodation of the larger metal cations.17 However, the monomeric units in [AM{Al(BDI-H)}]2 (AM = Rb, Cs) CDPs are strictly coplanar due to a crystallographic center of inversion, indicating that a twist is not required in these structures. Despite these differences, the Al···Al distance is largely consistent (e.g., [Rb{Al(NONDipp)}]2 = 5.548(1) Å, [Rb{Al(BDI-H)}]2 = 5.489(6) Å; [Cs{Al(NONDipp)}]2 = 5.752(1) Å, [Cs{Al(BDI-H)}]2 = 5.7334(17) Å/6.1086(19) Å).

The relative dimerization energies calculated for 2 AM[Al(BDI-H)] → [AM{Al(BDI-H)}]2 show a regular decrease as the size of the alkali metal increases.18 However, when the opposing solvation effects [polarizable continuum model (PCM) = benzene, which favor the monomer due to solvent–metal interactions] and dispersion effects (which favor the dimer through attractive interactions between ligands) are incorporated in the calculations, the trend is less well defined with, for example, the ΔG value for AM = Na (−21.1 kcal mol–1) less than that for AM = K (−25.4 kcal mol–1). We have noted a similar trend with the 2 AM[Al(NONDipp)] → [AM{Al(NONDipp)}]2 system,17 wherein PCM = toluene with a ΔG value for AM = Na (−26.7 kcal mol–1) less than that for AM = K (−33.6 kcal mol–1). In both cases, the calculation indicates the dimerization enthalpies for heavier alkali metal derivatives Rb and Cs trend toward being less exothermic (−19.6 kcal mol–1 {Rb}, −14.3 kcal mol–1 {Cs} for [(BDI-H)]2– system; −28.2 kcal mol–1 {Rb}, −24.9 kcal mol–1 {Cs} for [NONDipp]2– system). We consider these factors as important when examining the reactivity of these species, as we anticipate the monomeric alkali metal aluminyls to be considerably more reactive.

We have reported that the dimeric potassium aluminyl [K{Al(NONDipp)}]2 is active toward the oxidative addition of polar and non-polar E–H bonds, including Si–H, P–H, O–H, N–H, and H–H bonds.10,19 The synthesis is a convenient route to soluble alkali metal (hydrido) aluminates, K[Al(NONDipp)(E)(H)]−, which are in themselves an interesting class of molecular main group metal hydrides that offer the potential for further useful reactivity.20 To examine any AMM effects, we have selected the reaction of our aluminyl systems with phenylsilane (PhSiH3) as this can be benchmarked against other neutral and anionic Al(I) systems (Scheme 1).8a,21 We report herein the first examples of an oxidative addition reaction to a complete series of alkali metal aluminyls [AM{Al(NONDipp)}]2 (AM = Li, Na, K, Rb, Cs), thereby exploiting a rare opportunity to systematically examine the influence of the alkali metal counter ion on this fundamental reaction type as well as on the structure of the products formed.

Scheme 1. Oxidative Addition of Phenylsilane to Al(I) Complexes to Afford (silyl)(hydrido) Aluminum Products Al(BDIDipp)(H)(SiH2Ph), [K(12-c-4)2][(AdN-CH=CHC{SiMe3}2)Al(H)(SiH2Ph)] ([K(12-c-4)2][E(H)(SiH2Ph)]), and K[Al(NONDipp)(H)(SiH2Ph)] (K[B(H)(SiH2Ph)]).

Results and Discussion

The addition of phenylsilane to a diethyl ether (AM = Li) or toluene (AM = Na, Ka) solution of [AM{Al(NONDipp)}]2 yielded the corresponding aluminum(III) (silyl)(hydrido) complexes AM[Al(NONDipp)(H)(SiH2Ph)] (1-AM, Scheme 2). For the heavier congeners with AM = Rb and Cs, the reaction was carried out in hexane, resulting in precipitation of the crude product as a colorless solid. Purification was achieved by crystallization from Et2O (AM = Li, Na, K, Rb) or THF (AM = Cs), with the product isolated as the solvated species 1-AM·(solvent)n, (AM = Li, Na, K and Rb: solvent = Et2O, n = 1; AM = Cs: solvent = THF, n = 2).

Scheme 2. Synthesis of 1-AM, Isolated as 1-AM·(Et2O) (AM = Li, Na, K Rb) and 1-AM·(THF)2 for AM = Cs.

The 1H NMR spectra of the isolated products show two sharp singlets that each integrate as 6H for the SiMe2 groups of the NONDipp-ligand backbone, indicating a reduction in the molecular symmetry and consistent with a [Al(NONDipp)(X)(X′)]− (where X ≠ X′) substituted center. Distinct resonances for the SiH2 protons were observed as either a resolved doublet (AM = Li, Rb, Cs) or a broad singlet (AM = Na, K). We note a solvent-dependent chemical shift for this resonance, with a higher field signal observed when the 1H NMR spectra are acquired in THF-d8 compared with those obtained in C6D6 (or a C6D6 dominant solvent mixture). This is best illustrated for 1-Li·(Et2O) (δH 3.67 in C6D6, 3.18 in THF-d8) and 1-Cs·(THF)2 (δH 3.62 in C6D6/THF-d8 (4:1), 3.37 in THF-d8). Although it is not possible to unequivocally ascribe this shift to the presence of SiH2···AM interactions in the solution, it does suggest that changes in the solvation of the AM affect the environment of the [Al(NONDipp)(H)(SiH2Ph)]− component of these complexes.

In contrast to the previously reported products Al(BDIDipp)(H)(SiH2Ph) and [K(12-c-4)2][(AdN-CH=CH–C{SiMe3}2)Al(H)(SiH2Ph)] ([K(12-c-4)2][E(H)(SiH2Ph)]) (Scheme 1), for which a 29Si resonance was observed for the silyl ligand at δSi = −74.0,21 and δSi = −72.0,8a respectively, the corresponding 29Si NMR signals for 1-AM were not observed. Furthermore, the 1H NMR resonances for the AlH ligands could not be detected for any of the products, consistent with observations for related systems19,21 and attributed to the proximity of the quadrupolar 27Al nucleus (I = 5/2). The existence of both Al–H- and Si–H-containing groups was, however, verified from characteristic stretches in the IR spectra, where distinct absorptions were observed in the regions 1648–1686 and 2052–2084 cm–1, respectively.b

Despite the use of several types and combinations of donor groups in the supporting ligands at the aluminum center (vide supra), the 27Al NMR signal has not been reported for any of the parent aluminyl complexes, suggesting an inherent difficulty in observing a signal for these low-coordinate anionic species.5,7−9 That said, we have previously noted that the products of oxidative addition that contain aluminum in the +3 oxidation state are no longer silent in 27Al NMR experiments,10,19 and therefore, the appearance of a signal in the 27Al NMR spectra offers further supporting evidence for the formation of the desired products of oxidative addition. Each of the compounds 1-AM shows broad resonances in the 27Al NMR spectrum for the [Al(NONDipp)(H)(SiH2Ph)]− anion in the range δAl 121–127. In addition, a signal in the 7Li NMR spectrum at δLi 2.72 confirmed the presence of lithium in 1-Li·(Et2O).

X-ray diffraction data were collected on crystals of 1-AM·(Et2O) (AM = Li, Na, K, Rb) and 1-Cs·(THF)2. Collectively, these data offer a unique opportunity to examine the influence of the alkali metal on structural parameters for a series of (silyl) (hydrido) aluminate anions. Selected bond lengths and angles are collected in Table 1, with representative structures 1-Li·(Et2O), 1-Rb·(Et2O), and 1-Cs·(THF)2 shown in Figures 2–4, respectively.

Table 1. Selected Bond Lengths (Å) and Angles (°) for 1-AM·(Et2O) (AM = Li, Na, K, Rb) and 1-Cs·(THF)2.

| AM = Li | AM = Na | AM = K | AM = Rba | AM = Csb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al–Si3 | 2.4670(5) | 2.5088(4) | 2.5187(5) | 2.5275(6) | 2.5183(6) |

| Al–N1 | 1.8752(10) | 1.8542(10) | 1.8633(9) | 1.8808(11) | 1.8747(13) |

| Al–N2 | 1.8451(10) | 1.8772(9) | 1.8804(9) | 1.8693(11) | 1.8750(13) |

| Al–H1x | 1.62(2) | 1.58(2) | 1.60(2) | 1.58(2) | 1.56(2) |

| AM···H1x | 2.01(2) | 2.24(2) | 2.26(2) | 2.83(2) | 3.23(2) |

| AM···H2x | 2.43(2) | ||||

| AM–O2 | 1.896(3) | 2.2691(10) | 2.6923(10) | 2.8277(12) | 3.0171(14) |

| AM–O3 | 3.0501(13) | ||||

| Al···AM | 3.004(3) | 3.3261(6) | 3.7198(7) | 3.8464(4) | 4.1469(4) |

| N1–Al–N2 | 107.57(4) | 106.89(4) | 106.23(4) | 105.98(5) | 104.70(6) |

| N1–Al–Si3 | 116.64(3) | 114.12(3) | 112.29(3) | 120.05(4) | 117.91(5) |

| N2–Al–Si3 | 118.70(3) | 118.67(3) | 119.60(3) | 111.42(4) | 110.47(4) |

| Al–Si3–C* | C29: 113.46(4) | C29: 110.13(4) | C29: 110.17(4) | C29: 110.58(5) | C1: 112.71(5) |

Al = Al1, AM = Rb1, H1x = H1.

AM = Cs1, H1x = H1.

Figure 2.

Displacement ellipsoid plot (30% probability; selected atoms represented as sticks; H atoms except those of AlH and SiH2 omitted; Li···C1–C6 centroid included; dashed lines representing Li···H interactions) of 1-Li·(Et2O).

Figure 4.

Displacement ellipsoid plot (30% probability; selected atoms represented as sticks; H atoms except those of AlH and SiH2 omitted; Cs···C1–C6 and Cs···C7–C12 centroids included; dashed line representing Cs···H interaction) of 1-Cs·(THF)2.

All of the compounds in the series were isolated as molecular complexes consisting of the (silyl)(hydrido) aluminate anion [Al(NONDipp)(H)(SiH2Ph)]−, which was intimately involved with ether solvated alkali metal cations, “AM(Et2O)” (AM = Li, Na, K, Rb) or “AM(THF)2” (AM = Cs). The 1-AM·(Et2O) crystal structures are isomorphous (monoclinic, P21/c) for AM = Na, K, and Rb, with the outermost members 1-Li·(Et2O) and 1-Cs(THF)2 crystallizing in the monoclinic crystal system with space groups P21/n and I2/a, respectively. While we acknowledge that the precise location of hydrogen atoms cannot be determined due to the limitations of X-ray diffraction experiments, electron density consistent with the expected positions of the AlH and SiH2 hydrogen atoms were located in the electron difference map, assigned as hydrogen atoms, and freely refined. The resulting positions of these hydrogen atoms imply a combination of AlH···AM, SiH···AM interactions that support AM···π(arene) contacts in each structure that link the aluminate anion and alkali metal cation within each structure (vide infra).

The geometry at the aluminum atoms is best described as distorted tetrahedral defined by the chelated NONDipp-ligand and the newly installed silyl and hydrido ligands. The Al–N bond lengths in 1-AM·(solvent)n (range: 1.8451(10) Å–1.8808(11) Å) are not significantly (within 3σ) different to those in the parent aluminyls [AM{Al(NONDipp)}]2 (range: 1.8649(14) Å–1.905(3) Å) and do not allow a specific trend to be identified. We attribute this to the expected decrease in the radius upon oxidation from Al(I) to Al(III) being offset with the anticipated increase in the Al–N bond length when the coordination number rises from two to four.19 The N–Al–N angles reflect these similarities, with the values for 1-AM·(solvent)n [range: 104.70(6)–107.57(4)°] close to those observed in the starting aluminyls [range: 103.30(12)–108.13(4)°]. The Al–Si bond lengths increase regularly from AM = Li [Al–Si3 = 2.4670(5) Å] to AM = Rb [Al1–Si3 = 2.5275(6) Å], with a slight reduction for the cesium analogue 1-Cs·(THF)2 (Al1–Si3 = 2.5183(6) Å), possibly reflecting the increased coordination number at the AM due to the presence of two THF ligands. These values all fall within the range noted previously for four-coordinate neutral [Al(BDIDipp)(H)(SiH2Ph) = 2.4551(8) Å]21 and anionic ([E(H)(SiH2Ph)]− = 2.546(3) Å),8a compounds containing the Al–SiH2Ph ligand.

All of the variants have close contacts between the aluminum hydrido ligand and the alkali metal (Table 1), with distances less than the sum of the van der Waals radii [ΣVdW(Li,H) = 2.91 Å, ΣVdW(Na,H) = 3.37 Å, ΣVdW(K,H) = 3.85 Å; ΣVdW(Rb,H) = 4.13 Å; ΣVdW(Cs,H) = 4.53 Å].22 For the lighter alkali metals, these distances compare well with those in the dihydrido aluminate complexes (NONDipp)Al(μ-H)2Li(Et2O)2 [AlH···Li = 1.95(2) Å and 1.98(2) Å] and the dimeric [AM{Al(NONDipp)(H)2}]2 compounds [range AlH···Na: 2.30(2) Å–2.34(2) Å; range AlH···K: 2.72(2) Å–3.02(2) Å].10 To the best of our knowledge, however, 1-Rb·(Et2O) and 1-Cs·(THF)2 are the first structurally characterized examples of rubidium or cesium salts of (hydrido) aluminate anions, precluding meaningful comparisons.

The most prominent differences in the series of structures 1-AM·(solvent)n manifest in the nature and extent of the additional interactions between the AM cation and the anionic [Al(NONDipp)(H)(SiH2Ph)]− components. For the lightest member of the series 1-Li·(Et2O) (Figure 2), the ether-solvated lithium atom is located within the π-bonding range of the aryl ring of one of the Dipp-substituents (C1–C6), with an apparent additional SiH···Li interaction [H2x···Li = 2.43(2) Å]. In contrast, the silyl substituent is rotated about the Al–Si bond in the sodium, potassium, and rubidium congeners (e.g., 1-Rb·(Et2O) (Figure 3)) such that the Et2O solvated AM is located between two C6-aryl rings, one from a Dipp substituent (C1–C6) and the other belonging to the SiPh group (C29–C34). A similar orientation of the silyl substituent in 1-Cs·(THF)2 (Figure 4) also locates the solvated AM between two six-membered rings belonging to a Dipp substituent (C7–C12) and the SiPh group (C1–C6). This likely reflects a decrease in the tendency of the lithium to engage in Li···π(arene) interactions when compared with the larger (softer) alkali metals.

Figure 3.

Displacement ellipsoid plot (30% probability; selected atoms represented as sticks; H atoms except those of AlH and SiH2 omitted; Rb···C1–C6 and Rb···C29–C34 centroids included; dashed line representing Rb···H interaction) of 1-Rb·(Et2O).

We have examined the extent to which the AM interacts with the C6 rings for each of the complexes described in this study. In addition to basic evaluations involving distance and angle measurements to the centroid (Ct) of the C6-ring, we have used the criteria established by Alvarez and co-workers to quantify low hapticity (η1–η3) aryl interactions (Figure 5a).23 We are mindful of the difference between the transition metal systems examined previously that involved arguments concerning d-orbital occupancy and the current s-block metal complexes and have therefore used the established principles for geometric analysis and not an explanation of why these various hapticities are present. The Alvarez criteria define ρ1 as the ratio of d2/d1 and ρ2 as the ratio of d3/d1, where dn is the distance from the carbon to the AM, and d1 < d2 < d3 < d4 (Figure 5b). Using these relationships, an η1-hapticity is consistent with ρ1 ∼ ρ2 ≫ 1; η2-hapticity best fits the situation when d1 ∼ d2 < d3 and ρ2 > ρ1 ∼ 1, and for η3-hapticity, d1 ∼ d2 ∼ d3 and ρ2 ∼ ρ2 ∼ 1. Extending these definitions to higher hapticities according to the idealized positions, we include a simple measure of Δd4–3 = d4–d3, which would approach zero for idealized η4-hapticity (Figure 5c). We have attempted to quantify the AM···Dipp and AM···Ph interactions in the series 1-AM·(solvent)n compounds, using these criteria to map any trends related to the identity of the AM.

Figure 5.

(a) Plan projection of the idealized positions according to ηn-hapticities for n = 1–6; (b) definition of ρ1 and ρ2 according to the three shortest metal···C distances in AM···π(arene) complexes; (c) idealized η4-hapticity, introducing Δd4–3 (= d4–d3).

For all members of the series, we observe an increase in AM···Ct distance as the size of the cation increases from Li to Cs (Table 2), which coincides with an increase in the Ct···Ct distance. We also note that the plane normal-to-plane normal angle for the mean square planes defined by C6-rings and the Ct···AM···Ct angle also increase. These changes are expected as the size of the AM cation increases and are also consistent with what is predicted on the basis of a proposed increase in the hapticity of the arene rings as larger (softer) cations are present.24 To test this theory in more detail, we present the plan view of the AM above the C6-rings of the SiPh and Dipp-substituents for the isomorphous members of the series, 1-AM·(Et2O) (AM = Na, K, Rb) in Figure 6.

Table 2. Selected Bond Lengths (Å) and Angles (°) for AM Interactions with the C6-Rings in 1-AM·(Et2O) (AM = Li, Na, K, Rb) and 1-Cs·(THF)2.

| AM = Li | AM = Na | AM = K | AM = Rb | AM = Cs | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ct(Ph) | 2.9477(8) | 2.9722(7) | 3.0416(8) | 3.356(1) | |

| Ct(Dipp) | 2.197(3) | 2.7144(7) | 2.9135(6) | 3.0078(7) | 3.2852(9) |

| Ct···Ct (distance) | 5.0335(9) | 5.3067(8) | 5.5037(9) | 6.0513(9) | |

| C6···C6 (angle)a | 43.46(5) | 45.21(4) | 45.50(5) | 51.18(6) | |

| Ct···AM···Ct (angle) | 125.44(2) | 128.74(2) | 130.995(2) | 131.35(2) |

Plane normal-to-plane normal angle for mean square planes defined by C6-rings.

Figure 6.

Plan view of the position of the alkali metals above the C6-rings of the SiPh and Dipp substituents for the isomorphous compounds 1-AM·(Et2O) (AM = Na, K, Rb). Numbers correspond to the C-atom labels from the X-ray diffraction data.

Visual inspection of the sodium derivative clearly indicates an η2-coordination to C29 and C34 of the phenyl group, supported by the calculated ρ2 (1.13) > ρ1 (1.00) (Table 3). However, this coordination mode is not as clearly defined in the heavier K and Rb derivatives, where the reduced ρ2 values (K = 1.06, Rb = 1.07) and relative decrease in the AM···C30 distance indicate a shift toward an η3-coordination. Indeed, it may be argued that the coordination is better described as η4- for 1-K·(Et2O) and 1-Rb·(Et2O) (Figure 5c), including the Δd4–3 values (K = 0.02, Rb = 0.05), which show that the AM···C33 distances are only marginally greater than the corresponding AM···C30 values.

Table 3. Selected Bond Lengths (Å) and Angles (°) for AM Interactions with the C6-Rings in 1-AM·(Et2O) (AM = Li, Na, K, Rb) and 1-Cs·(THF)2.

| AM = Li | AM = Na | AM = K | AM = Rb | AM = Cs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ph | ||||

| C29: 2.861(1) d1 | C29: 3.101(1) d2 | C29: 3.199(2) d1 | C7: 3.602(2) | |

| C30: 3.232(2) d3 | C30: 3.271(1) d3 | C30: 3.325(2) d3 | C8: 3.538(2) | |

| C31: 3.599(2) | C31: 3.447(2) | C31: 3.472(2) | C9: 3.508(2) | |

| C32: 3.626(2) | C32: 3.461(2) | C32: 3.493(2) | C10: 3.556(2) | |

| C33: 3.284(2) | C33: 3.300(1) (d4) | C33: 3.373(2) (d4) | C11: 3.602(2) | |

| C34: 2.871(1) d2 | C34: 3.097(1) d1 | C34: 3.206(2) d2 | C12: 3.620(2) | |

| ρ1 = 1.00 | ρ1 = 1.00 | ρ1 = 1.00 | ||

| ρ2 = 1.13 | ρ2 = 1.06 | ρ2 = 1.07 | ||

| Δd4–3 | 0.02 | 0.05 | ||

| Dipp | ||||

| C1: 2.483(3) | C17: 3.018(1) d3 | C17: 3.292(1) (d4) | C1: 3.394(2) | C1: 3.491(2) |

| C2: 2.538(3) | C18: 2.887(1) d2 | C18: 3.428(1) | C2: 3.482(2) | C2: 3.502(2) |

| C3: 2.625(3) | C19: 2.882(1) d1 | C19: 3.313(1) | C3: 3.358(1) (d4) | C3: 3.663(2) |

| C4: 2.688(3) | C20: 3.035(1) (d4) | C20: 3.128(1) d2 | C4: 3.200(1) d2 | C4: 3.767(2) |

| C5: 2.687(3) | C21: 3.229(1) | C21: 3.068(1) d1 | C5: 3.180(1) d1 | C5: 3.751(2) |

| C6: 2.613(3) | C22: 3.259(2) | C22: 3.158(1) d3 | C6: 3.288(2) d3 | C6: 3.617(2) |

| ρ1 = 1.00 | ρ1 = 1.02 | ρ1 = 1.01 | ||

| ρ2 = 1.05 | ρ2 = 1.03 | ρ2 = 1.02 | ||

| Δd4–3 | 0.13 | 0.07 | ||

Similar arguments may be presented for the hapticity of the C6-ring of the Dipp substituent, where a larger difference in the ρ2 versus ρ1 value for 1-Na·(Et2O) agrees with a shift to higher hapticities for the heavier congeners (Table 3). The larger Δd4–3 value for 1-K·(Et2O) 0.13 best fits the η3-coordination, whereas the Δd4–3 value of 0.07 for 1-Rb·(Et2O) indicates a shift toward η4-hapticity. These data therefore support the hypothesis that within an isomorphous series of compounds, an increase in hapticity is observed as the size of the alkali metal increases.

When a crude reaction mixture containing Rb[Al(NONDipp)(H)(SiH2Ph)] was purified by crystallization from a layered hexane/THF mixture, an unexpected product was obtained (Scheme 3). Analytical data suggested the formation of the rubidium analogue of 1-Cs·(THF)2, with NMR and IR spectroscopic data consistent with the [Al(NONDipp)(H)(SiH2Ph)]− anion and elemental analysis consistent with [Rb(THF)2][Al(NONDipp)(H)(SiH2Ph)]. However, analysis by single crystal X-ray diffraction revealed a remarkably different structure: a polymer consisting of the heteroleptic tris-rubidium bis-aluminum cation [{Rb(THF)4}2(Rb{Al(NONDipp)(H)(SiH2Ph)}2)]+ and the non-solvated heteroleptic [Rb{Al(NONDipp)(H)(SiH2Ph)}2]− anion (2, Table 4, Figure 7). Compound 2 therefore represents a unique example of a rubidium rubidiate, where rubidium is present in both the cationic and anionic moieties, extending the series of known lithium lithiates,25 sodium sodiates,26 and potassium potassiates27 to the next member of the Group 1 metals.

Scheme 3. Fortuitous Synthesis of Compound 2.

Table 4. Selected Bond Lengths (Å) and Angles (°) for 2b.

| aniona | cationa | |

|---|---|---|

| Al–Si | 2.5071(10) | 2.5032(9) |

| Al–Nc | 1.876(2) | 1.872(2) |

| Al–Nd | 1.867(2) | 1.885(2) |

| Al–He | 1.56(2) | 1.57(3) |

| Rb···He | 2.78(2) | 2.87(3) |

| Rb···Hf | 2.98(3) | 3.08(3) |

| Rb2–O2 | 2.9386(16) | |

| Al···Rb | 3.8173(7) | 3.7918(7) |

| N–Al–Nc,d | 107.30(9) | 106.14(9) |

| N–Al–Sic | 109.15(7) | 117.95(7) |

| N–Al–Sid | 118.81(7) | 108.13(7) |

| Al–Si–Cg | 122.56(8) | 124.37(8) |

Al = Al1; Si = Si1; Rb = Rb1.

Al = Al2; Si = Si4; Rb = Rb3.

anion, N = N1; cation, N = N3.

anion, N = N2; cation, N = N4.

anion, H = H1; cation, H = H4.

anion, H = H2; cation, H = H5.

anion, C = C1; cation, C = C35.

Figure 7.

Displacement ellipsoid plot (30% probability; selected atoms represented as sticks; H atoms except those of AlH and SiH2 omitted; Rb1···C7–C12 and Rb2···C41–C46 centroids included; dashed lines representing Rb···H interactions) of compound 2 (′ 2 – x, −y, 1 – z; ″ = 1 – x, 2 – y, −z). (a) [Rb{Al(NONDipp)(H)(SiH2Ph)}2]− anion; (b) [{Rb(THF)4}2(Rb{Al(NONDipp)(H)(SiH2Ph)}2)]+ cation.

In contrast to 1–Rb·(Et2O), the orientation of the silyl ligand in both the cationic and anionic moieties of 2 most closely resembles that noted in the lithium complex 1-Li·(Et2O), precluding any Rb···Ph interactions. In both the cation and anion, the Rb atoms are therefore stabilized by AlH···Rb [2.78(2) Å and 2.87(3) Å] and SiH···Rb [2.98(3) Å and 3.08(3) Å] contacts, with additional Rb···π(arene) contacts to one of the Dipp substituents. As both Rb1 and Rb3 are located on an inversion center, these atoms each engage in a total of 4 × Rb···H and 2 × Rb···π(arene) interactions, with no direct bonding to the THF. However, in the cationic moiety, the outer THF-solvated Rb cations also bond to the O-atom of the adjacent NONDipp-ligands, to propagate the polymeric cation–anion arrangement of 2. The interaction of the oxygen atom with additional cations is not common for the NONRligand,28 with the oxygen typically adopting a purely structural role in the ligand backbone.

Conclusions

In summary, we have been able to examine the oxidative addition of phenylsilane to a complete series of dimeric aluminyls, [AM{Al(NONDipp)}]2 for AM = Li, Na, K, Rb, and Cs. Although we did not observe any obvious alkali metal effects in these reactions (since they all proceeded smoothly under ambient conditions), the structurally similar products allowed a systematic study of the role of AM in stabilizing the resulting (silyl)(hydrido) aluminate complexes. The products were crystallized from Et2O (Li, Na, K, Rb) or THF (Cs) to give monomeric [AM(Et2O)][Al(NONDipp)(H)(SiH2Ph)] and [Cs(THF)2][Al(NONDipp)(H)(SiH2Ph)], respectively. Crystallographic analysis shows that the solvated AM atoms are each supported by an AlH···AM contact, in addition to SiH···AM (AM = Li and Rb) and AM···π(arene) interactions with a Dipp substituent (Li–Cs) and the phenyl group (Na–Cs). Detailed analysis of the hapticity in an isomorphous series of Na, K, and Rb complexes indicates a tendency for the larger alkali metals to bond via an increased hapticity, a feature that can contribute toward variations in reactivity down the group. In addition, we discovered that when the Rb analogue was crystallized from a mixed hexane/THF solvent system, a novel rubidium rubidiate salt was isolated, extending the series of lithium lithiates, sodium sodiates, and potassium potassiates to the next heaviest Group 1 metal member and leaving only the cesium cesiate to be discovered.

Acknowledgments

G.M.B., T.X.G., and R.E.M. thank the EPSRC for generous financial support (EP/S029788/1). M.P.C., J.R.F., and M.J.E. acknowledge government funding from the Marsden Fund Council, managed by Royal Society Te Apa̅rangi (grant no: MFP-VUW2020). The authors wish to acknowledge a Victoria University of Wellington doctoral scholarship (M.J.E.).

Data used within this manuscript can be accessed at https://doi.org/10.15129/477fd1d6-12b7-441b-a1d1-931f08ce47b8.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.inorgchem.2c03010.

Experimental methods, crystallographic information, NMR spectra, IR data, and melting point data (PDF)

Author Contributions

The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Footnotes

Data pertaining to the previously reported addition of phenylsilane to the potassium aluminyl [K{Al(NONDipp)}]2 have been included in this discussion to facilitate the mapping of trends within the full series of aluminyl compounds.

Unfortunately, the sensitivity of 1-Li·(Et2O) towards air and moisture precluded the collection of any meaningful IR data due to rapid decomposition. A representative spectrum is included in the Supporting Information (Figure S74).

Supplementary Material

References

- Dohmeier C.; Robl C.; Tacke M.; Schnöckel H. The Tetrameric Aluminum(I) Compound [{Al(η5-C5Me5)}4]. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1991, 30, 564–565. 10.1002/anie.199105641. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Hobson K.; Carmalt C. J.; Bakewell C. Recent Advances in Low Oxidation State Aluminium Chemistry. Chem. Sci. 2020, 11, 6942–6956. 10.1039/d0sc02686g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Liu Y.; Li J.; Ma X.; Yang Z.; Roesky H. W. The Chemistry of Aluminum(I) with β-Diketiminate Ligands and Pentamethylcyclopentadienyl-Substituents: Synthesis, Reactivity and Applications. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2018, 374, 387–415. 10.1016/j.ccr.2018.07.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Zhong M.; Sinhababu S.; Roesky H. W. The Unique β-Diketiminate Ligand in Aluminum(I) and Gallium(I) Chemistry. Dalton Trans. 2020, 49, 1351–1364. 10.1039/c9dt04763h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui C.; Roesky H. W.; Schmidt H.-G.; Noltemeyer M.; Hao H.; Cimpoesu F. Synthesis and Structure of a Monomeric Aluminum(I) Compound [{HC(CMeNAr)2}Al] (Ar = 2,6-iPr2C6H3): A Stable Aluminum Analogue of a Carbene. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2000, 39, 4274–4276. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu T.; Nikonov G. I. Oxidative Addition and Reductive Elimination at Main-Group Element Centers. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 3608–3680. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hicks J.; Vasko P.; Goicoechea J. M.; Aldridge S. Synthesis Structure and Reaction Chemistry of a Nucleophilic Aluminyl Anion. Nature 2018, 557, 92–95. 10.1038/s41586-018-0037-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hicks J.; Vasko P.; Goicoechea J. M.; Aldridge S. The Aluminyl Anion: A New Generation of Aluminium Nucleophile. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 1702–1713. 10.1002/anie.202007530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Schwamm R. J.; Anker M. D.; Lein M.; Coles M. P. Reduction vs. Addition: The Reaction of an Aluminyl Anion with 1,3,5,7-Cyclooctatetraene. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 1489–1493. 10.1002/anie.201811675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Schwamm R. J.; Coles M. P.; Hill M. S.; Mahon M. F.; McMullin C. L.; Rajabi N. A.; Wilson A. S. S. A Stable Calcium Alumanyl. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 3928–3932. 10.1002/anie.201914986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Grams S.; Eyselein J.; Langer J.; Färber C.; Harder S. Boosting Low-Valent Aluminum(I) Reactivity with a Potassium Reagent. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 15982–15986. 10.1002/anie.202006693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Koshino K.; Kinjo R. Construction of σ-Aromatic AlB2 Ring via Borane Coupling with a Dicoordinate Cyclic (Alkyl)(Amino)Aluminyl Anion. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 9057–9062. 10.1021/jacs.0c03179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Yan C.; Kinjo R. A Three-Membered Diazo-Aluminum Heterocycle to Access an Al=C π Bonding Species. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202211800 10.1002/anie.202211800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurumada S.; Takamori S.; Yamashita M. An Alkyl-Substituted Aluminium Anion with Strong Basicity and Nucleophilicity. Nat. Chem. 2020, 12, 36–39. 10.1038/s41557-019-0365-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans M. J.; Anker M. D.; McMullin C. L.; Neale S. E.; Coles M. P. Dihydrogen Activation by Lithium- and Sodium-Aluminyls. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 22289–22292. 10.1002/anie.202108934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Hicks J.; Heilmann A.; Vasko P.; Goicoechea J. M.; Aldridge S. Trapping and Reactivity of a Molecular Aluminium Oxide Ion. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 17265–17268. 10.1002/anie.201910509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Anker M. D.; Coles M. P. Aluminium-Mediated Carbon Dioxide Reduction by an Isolated Monoalumoxane Anion. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 18261–18265. 10.1002/anie.201911550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Anker M. D.; McMullin C. L.; Rajabi N. A.; Coles M. P. Carbon–Carbon Bond Forming Reactions Promoted by Aluminyl and Alumoxane Anions: Introducing the Ethenetetraolate Ligand. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 12806–12810. 10.1002/anie.202005301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Heilmann A.; Hicks J.; Vasko P.; Goicoechea J. M.; Aldridge S. Carbon Monoxide Activation by a Molecular Aluminium Imide: C–O Bond Cleavage and C–C Bond Formation. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 4897–4901. 10.1002/anie.201916073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Evans M. J.; Gardiner M. G.; Anker M. D.; Coles M. P. Extending Chain Growth Beyond C1 → C4 in CO Homologation: Aluminyl Promoted Formation of the [C5O5]5– Ligand. Chem. Commun. 2022, 58, 5833–5836. 10.1039/d2cc01554d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Heilmann A.; Roy M. M. D.; Crumpton A. E.; Griffin L. P.; Hicks J.; Goicoechea J. M.; Aldridge S. Coordination and Homologation of CO at Al(I): Mechanism and Chain Growth, Branching, Isomerization, and Reduction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 12942–12953. 10.1021/jacs.2c05228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentner T. X.; Mulvey R. E. Alkali-Metal Mediation: Diversity of Applications in Main-Group Organometallic Chemistry. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 9247–9262. 10.1002/anie.202010963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Robertson S. D.; Uzelac M.; Mulvey R. E. Alkali-Metal-Mediated Synergistic Effects in Polar Main Group Organometallic Chemistry. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 8332–8405. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.9b00047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Gil-Negrete J. M.; Hevia E. Main Group Bimetallic Partnerships for Cooperative Catalysis. Chem. Sci. 2021, 12, 1982–1992. 10.1039/d0sc05116k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy M. M. D.; Hicks J.; Vasko P.; Heilmann A.; Baston A.-M.; Goicoechea J. M.; Aldridge S. Probing the Extremes of Covalency in M–Al bonds: Lithium and Zinc Aluminyl Compounds. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 22301–22306. 10.1002/anie.202109416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grubel K.; Brennessel W. W.; Mercado B. Q.; Holland P. L. Alkali Metal Control over N–N Cleavage in Iron Complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 16807–16816. 10.1021/ja507442b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentner T. X.; Evans M. J.; Kennedy A. R.; Neale S. E.; McMullin C. L.; Coles M. P.; Mulvey R. E. Rubidium and Caesium Aluminyls: Synthesis, Structures and Reactivity in C–H Bond Activation of Benzene. Chem. Commun. 2022, 58, 1390–1393. 10.1039/d1cc05379e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grams S.; Mai J.; Langer J.; Harder S. Alkali Metal Influences in Aluminyl Complexes. Dalton Trans. 2022, 51, 12476–12483. 10.1039/d2dt02111k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans M. J.; Anker M. D.; Coles M. P. Oxidative Addition of Hydridic, Protic, and Nonpolar E–H Bonds (E = Si, P, N, or O) to an Aluminyl Anion. Inorg. Chem. 2021, 60, 4772–4778. 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.0c03735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy M. M. D.; Omaña A. A.; Wilson A. S. S.; Hill M. S.; Aldridge S.; Rivard E. Molecular Main Group Metal Hydrides. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 12784–12965. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.1c00278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu T.; Korobkov I.; Nikonov G. I. Oxidative Addition of σ Bonds to an Al(I) Center. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 9195–9202. 10.1021/ja5038337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantina M.; Chamberlin A. C.; Valero R.; Cramer C. J.; Truhlar D. G. Consistent van der Waals Radii for the Whole Main Group. J. Phys. Chem. A 2009, 113, 5806–5812. 10.1021/jp8111556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falceto A.; Carmona E.; Alvarez S. Electronic and Structural Effects of Low-Hapticity Coordination of Arene Rings to Transition Metals. Organometallics 2014, 33, 6660–6668. 10.1021/om5009583. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson M. G.; Garcia-Vivo D.; Kennedy A. R.; Mulvey R. E.; Robertson S. D. Exploiting σ/π Coordination Isomerism to Prepare Homologous Organoalkali Metal (Li, Na, K) Monomers with Identical Ligand Sets. Chem.—Eur. J. 2011, 17, 3364–3369. 10.1002/chem.201003493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pöppler A.-C.; Granitzka M.; Herbst-Irmer R.; Chen Y.-S.; Iversen B. B.; John M.; Mata R. A.; Stalke D. Characterization of a Multicomponent Lithium Lithiate from a Combined X-Ray Diffraction, NMR Spectroscopy, and Computational Approach. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 13282–13287. 10.1002/anie.201406320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark N. M.; García-Álvarez P.; Kennedy A. R.; O’Hara C. T.; Robertson G. M. Reactions of (−)-Sparteine with Alkali Metal HMDS Complexes: Conventional Meets the Unconventional. Chem. Commun. 2009, 5835–5837. 10.1039/b908722b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clegg W.; Horsburgh L.; Mulvey R. E.; Ross M. J. Potassium Potassiate Contact Ion Pair Polymer Synthesised by Metallation of a Dihydrotriazine. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1994, 2393–2394. 10.1039/c39940002393. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schwamm R. J.; Randow C. A.; Mouchfiq A.; Evans M. J.; Coles M. P.; Robin Fulton J. Synthesis of Heavy N-Heterocyclic Tetrylenes: Influence of Ligand Sterics on Structure. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2021, 2021, 3466–3473. 10.1002/ejic.202100447. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.