Abstract

Barbados has a rich traditional use of medicinal plants, especially among the older population who may have a chronic noncommunicable disease. This study aims to identify possible drug–herb interactions between popular herbal remedies used to manage elevated blood pressure and conventional antihypertensive drugs. In this study, in silico molecular docking experiments with AutoDock Vina (Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA), a part of Yasara Structure software, version 20.12.24, were used to screen 30 potential phytochemicals for drug interactions from 11 popular plants in Barbados that are used for high blood pressure and could influence the pharmacology of the most prescribed antihypertensive drugs in Barbados. Thiazide and thiazide-like diuretics, calcium channel blockers (CCBs), angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE-I), and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) are the most prescribed antihypertensive drugs. Twenty-seven phytochemicals show dissociation constants (Kd) < 10 μM with pharmacological drug targets. Catharanthus roseus (L.) G. Don, Phyllanthus niruri L., Petroselinum crispum (Mill.) Fuss, and Lantana involucrata L. contain various compounds that show high binding affinities in all experiments. Possible interactions could affect renal excretion (thiazide-like diuretics), CYP metabolism (CCBs), absorption (ACE-I), hepatic CYP, and phase II metabolism (ARB). Oleanolic acid shows high binding affinities to almost all protein targets. This study also reveals potential candidates for the drug targets: T-type Cav3.3 (psychiatric diseases), PEPT1/2 (influencing bioavailability), and BK channel (epilepsy). Twenty-seven of 30 phytochemicals from C. roseus (L.) G. Don (Madagascar periwinkle), P. niruri L. (Seed under leaf), P. crispum Mill. Fuss (Parsley), and L. involucrata L. (Rock sage) have potential binding affinities with pharmacological targets of frequently prescribed antihypertensive drugs in Barbados and are likely to cause drug interactions. Compounds that are similar to naringin (e.g., astragalin, rutin, and quercitrin) and compounds that bind to OATP1, PEPT1/2, and enzymes involved in the metabolism of CCBs may be clinically relevant for further research. There should be greater awareness of potential drug–herb interactions, and further in vitro and in vivo studies are needed to unravel the exact effects on the pharmacology.

Introduction

The Caribbean, inclusive of Barbados, has a rich traditional use of medicinal plants. These practices are historically linked to ancestral influences from West Africa, Europe, and the original inhabitants the Amerindians. Also, generational knowledge has been passed on to subsequent generations by shamans, curanderos, traditional healers, and herbalists.1 The older and more rural population is tied closer to these traditional practices and use herbal remedies more often for various ailments and diseases than their younger counterparts.1,2 The older population in Barbados has one or more chronic conditions and may use different medicines concomitantly.3 Logically, the risk for drug–herb interactions is higher in this specific group of persons. Drug interactions are defined as the direct or indirect interaction of two or more drugs and substances that can alter the pharmacodynamics or pharmacokinetics of either drug or substance. Thus, persons who practice the use of two or more drugs concomitantly are at a heightened risk of drug interactions. As suggested by its categorization, drug–herb interactions are characterized by an interaction between a drug and a botanical medicine. To date, the mechanisms of many drug–herb interactions are unknown. Also, the knowledge of most health professionals in the Caribbean and internationally about herbal preparations is limited.1,4 Therefore, when drug–herb interactions occur, they cannot recognize them and intervene as deemed appropriate.1

The prevalence of hypertension in Barbados and the rest of the Caribbean is relatively high compared with that in other countries5 and provides the basis for the investigation of potential drug–herb interactions with antihypertensive drugs. It is estimated that 55% of the black population in Barbados within the age group of 40–80 years has hypertension.5−7 Physicians primarily treat hypertension in the public and private healthcare sectors. According to the Barbados Drug Service, the most prescribed antihypertensive drugs in Barbados are thiazide and thiazide-like diuretics (TD), calcium channel blockers (CCBs), angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), and β-blockers with prescription rates of 70, 42, 40, and 19%, respectively.8,9

These drug classes may differ among their biological targets in their pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics, so different target proteins at various physiological sites may be involved in the pharmacological effects of each drug.10,11 Also, each drug class has its own toxicological (side effects) profile. Therefore, it is essential to be aware of each drug class’s characteristics, which are summarized briefly in the following table (Table 1).

Table 1. Summary of Some Important Pharmacological Characteristics of Thiazide and Thiazide-Like Diuretics (TD), Calcium Channel Blockers (CCBs), Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitors (ACE-I), and Angiotensin Receptor Blockers (ARBs).

| drug class | pharmacodynamics and therapeutic considerations | pharmacokinetics |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| absorption | distribution | metabolism | excretion | ||

| TD | Blocking NaCl symporter in the distal tubules causing diuresis and lowering of blood pressure | Most compounds are well absorbed after oral administration; neither the rate nor extent is affected by food.15 | Repeated daily doses of bendroflumethiazide do not accumulate in patients. It follows linear elimination kinetics with doses between 2.5 and 10 mg.15 | Bendroflumethiazide is mainly metabolized hepatically.15 Hyponatremia and hypokalemia are potential side effects in the elderly and patients with liver dysfunctions.15 | Most compounds are secreted directly in the proximal tubules, except bendroflumethiazide.15 Organic anion transporters 1 and 3 (OAT1, OAT3) and multidrug-resistance-associated-protein-2 (MRP2) have a key role in tubular secretion.12 |

| Indirectly activates the renin–angiotensin aldosterone system (RAAS) | |||||

| Causes vasodilatation, which has a minor role.12 | |||||

| Disruptions in the electrolyte balance can provoke encephalopathy.12−14 | |||||

| CCBs | Dihydropyridines (e.g., amlodipine and nifedipine) are used in the treatment of hypertension. | Are well absorbed from the GI tract.16,17 | The plasma concentrations of nifedipine correlate with the blood pressure, heart rate, negative ionotropic effects, and lower esophageal sphincter pressure.16 | Nifedipine has a high first-pass effect and is metabolized mainly by cytochrome P4503A4 (CYP3A4).16,17 Amlodipine has a longer elimination half-life than nifedipine.16 In elderly and liver dysfunction patients, the elimination half-life of nifedipine is doubled due to reduced hepatic blood flow and reduced first-pass metabolism.16 | Metabolites of nifedipine and amlodipine are excreted by the kidneys.16,17 |

| Inhibiting allosterically the α1 subunit (dihydropyridine binding site) of the L-type calcium channels, causing vasodilatation of the smooth muscles in arteries and arterioles.12 | |||||

| ACE-I | Inhibits the conversion of angiotensin I to the potent vasoconstrictor angiotensin II by blocking ACE resulting in the reduction of arterial pressure and reducing cardiac load.12 | Food has no effect on the absorption phase of enalapril, in contrast to captopril food that decreases the absorption of captopril by 50%.18 | In hypertensive patients, the plasma concentration of enalaprilic acid correlates with the blood pressure-lowering effect.18 Enalapril and enalaprilic acid bound approximately 50% to plasma proteins.17 Steady state is reached after the 4th day of dosing, and no accumulation has been seen after repeated dosages. Enalaprilic acid distributes to most of the tissues, especially to the kidneys and vascular tissues.17 | Some ACE-I act directly (e.g., lisinopril), whereas others are prodrugs (enalapril). The metabolite enalaprilic acid is more potent than enalapril.18 | Enalapril is excreted mainly by the kidneys; patients with a renal clearance <30 mL/min accumulation of enalaprilat can take place.17 |

| Toxicity is mainly related to the presence of the sulfhydryl group and not to the mechanism of action.18 Potential side effects of ACE inhibitors are dry cough, angioedema, orthostatic hypotension, especially in heart failure patients using loop diuretics, renal failure in patients with renal artery stenosis, and hyperkalemia.12 | |||||

| ARBs | Blocking angiotensin II receptor type 1 (AT1).12,19 Also, ARBs can cause hyperkalemia, renal impairment, and hypotension.12,19 | The absorption of losartan is fast, and after oral administration losartan is metabolized by hepatic CYP enzymes. Food decreases the absorption and lowers the Cmax, but the AUC is not affected by food. However, food decreases the AUC of valsartan by 40% and Cmax by 50%.19 | Both losartan and valsartan are highly bound to plasma proteins, especially albumin. The plasma binding to albumin for losartan and valsartan is, respectively, 98.7% and 94%. After repeated administration, no accumulation occurs.19 Bioavailability of losartan is around 33%. The Cmax and AUC increase linearly with increasing dose. In elderly patients, the AUC of valsartan and half-life is higher, 70% and prolonged with 35%, respectively.19 | Losartan is metabolized by CYP2C9. The metabolite EXP3174 is 10–40 times more potent than losartan. Liver dysfunction and grapefruit juice affect the AUC and clearance of losartan.19 | In the elderly, the AUC is increased by 70% and the clearance is prolonged by 13%. In patients with liver dysfunctions, the AUC is doubled, and the clearance is 50% lower.19 Valsartan is not metabolized by CYP enzymes; it is converted to inactive metabolites. |

Cheminformatics techniques inclusive of molecular docking, homology modeling, and related computations were used to explore the potential pharmacological interactions20−22 between the four most prescribed classes of antihypertensive drugs with popular medicinal plants in Barbados that are used to lower high blood pressure. This work can help to sensitize the public and physicians about potential drug–herb interactions and support further in vitro and in vivo studies to investigate the exact effects of these compounds on the pharmacology of these drugs.

Materials and Methods

Selection of Antihypertensive Drugs

The most frequently prescribed antihypertensive drug classes in Barbados were obtained from the Barbados Drug Service, an agency of the Ministry of Health and Wellness, which facilitates the procurement and distribution of pharmaceutical products on the island.23 These drug classes were the thiazide and thiazide-like diuretics (TD), calcium channel blockers (CCBs), angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), and β-blockers with prescription rates of 70, 42, 40, and 19%, respectively. Structure data files (SDF) with the 3-dimensional (3D) chemical structure of each drug were downloaded from the PubChem database.24 Each structure was cleaned from waste molecules (e.g., water, ions, etc.), and energy minimization was performed with the AMBER03 force field in Yasara Structure Software version 20.12.24 (YASARA Biosciences; Austria).25,26 Thereafter, a multiligand SDF was composed as a compound library.

Screening and Selection of Proteins Involved in the Pharmacology

The protein drug targets involved in the pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of each antihypertensive drug were identified in the DrugBank database.27 The known pharmacological action and the UniProtID were noted for each protein. An overview of all potential protein targets for each drug is outlined in Table S1. Based on each specific UniProtID, Protein Data Bank (PDB) files with the 3D protein structures were selected from the UniProt database.28 Preferable selection conditions were X-ray crystallography structures and holo-structures with resolution < 2.0 Å. The files were downloaded from the PDB.29 The apo-structure was selected in case there was no available protein structure with a bound ligand. If no PDB file or proper structures were available, structures were obtained by homology modeling using SWISS-MODEL (Biozentrum, University of Basel).30

Protein 3D structures were cleaned from waste compounds (e.g., water, ions, lipids, etc.), except for cofactors. The quality of the obtained homology models was given by the global model quality estimate (GMQE) and QMEANDisCo global score; see Appendix II; Table S2. An overall model quality estimate between 0 and 130,31 and a QMEANDisCo score <0.6 are expected of low-quality models.31

Selection of the Medicinal Plants and Phytochemicals

Medicinal plants used in Barbados for managing elevated blood pressure were identified from the book “Medicinal Plants of Barbados for the Treatment of Communicable and Non-communicable Diseases” authored by D.H. Cohall.1 The phytochemical composition of each plant was verified from Dr. Duke’s Phytochemical and Ethnobotanical Database.32 Only compounds with a known blood pressure-lowering effect were selected for in silico experiments. Words that were associated with this effect include “hypotensive”, “antihypertensive”, “diuretic”, “vasodilator”, “ACE inhibitor”, “β-blocker”, “calcium antagonist”, and “ARB”. The plants with their scientific name, common Barbadian name, method of preparation, phytoconstituents (inclusive of the part of the plant) with a known blood pressure-lowering effect, and corresponding references are listed in Table S3. Eleven (11) plants were selected, and three different phytochemicals from each plant were selected for the analysis. SDFs with 3D chemical structures for these phytochemicals were downloaded from the PubChem database. Energy minimization was done for each structure and added to the multiligand SDF library. The structure formula, chemical group, and PubChem CID code were noted.

Preparing Protein Structures and Homology Modeling

PDB files with the protein holo-structure, the ligand, and the protein structure were saved separately as “name_ligand.yob or name_receptor.yob”. Local docking was performed with the macro “dock_runlocal.mcr”. The ligand was deleted, and the protein structure with the setup simulation cell was saved as “name_receptor.sce” as the final file for the molecular docking experiments. Energy minimization was unnecessary since the macro-local docking contains this step. For proteins with the apo-structure, the simulation cell was established using information on the molecular binding from the literature (see Table S2). For proteins with no specific binding pocket, energy minimization was done, and global docking was performed.

Molecular Docking Experiment

In previous studies, AutoDock Vina (Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA)33 as part of Yasara Structure software, version 20.12.24,25 was used to perform molecular docking to predict ligand–protein binding affinities.21,34 AutoDock Vina estimates binding energies of various docking poses through a combination of knowledge-based potentials and empirical scoring functions. The predicted binding energies by AutoDock Vina correlate reasonably well with experimental values. The standard error between calculated energies by AutoDock Vina and experimentally determined energies is 2.85 kcal/mol.33 Since the dissociation constant (Kd) is related to the binding energy (dG = RT*Ln(Kd)),35 results of binding affinities are presented as dissociation constants. Docking was done with 8 runs per ligand with the AMBER03 force field. Yasara presented Kd in picomolars (pM). Since ligands with a Kd of μM (10–6 mol/L), nM (10–9 mol/L), and pM (10–12 mol/L) are associated with, respectively, moderate, high, and extremely high binding affinities, respectively,36Kd values were converted to μM. Assuming that ligands with <10 μM are potential binders, Kd values above 10 μM were excluded from the final results. Logically, a lower dissociation constant is associated with a higher binding affinity.

Results

Pharmacotherapy for Hypertension in Barbados

The eleven (11) most prescribed antihypertensive drugs in Barbados based on data from the Barbados Drug Service are shown in Table 2. Proteins involved in the pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of these selected drugs are shown in Table 3 (see Table S2 for a complete description of the included proteins).

Table 2. Most Prescribed Antihypertensive Drugs in Barbados.

| thiazide and thiazide-like diuretics | calcium channel blockers (CCB) | angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE-I) | angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) |

|---|---|---|---|

| bendroflumethiazide | amlodipine | enalapril | valsartan |

| indapamide | nifedipine | lisinopril | losartan |

| chlorthalidone | ramipril | ||

| natrixam (indapamide/amlodipine) |

Table 3. Selected Proteins That Are Likely to be Involved in the Pharmacodynamics and Pharmacokinetics (Metabolism, Distribution, Excretion, and Absorption) of the Selected Antihypertensive Drugsa.

| drug class | pharmacodynamic biological targets | pharmacokinetic

biological targets |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| metabolism | distribution | excretion | absorption | ||

| thiazide and thiazide-like diuretics | solute carrier family 12 member 3 (NaCl symporter, NCC) | CYP3A4 | albumin | solute carrier family 22 member 6 (OAT1) | |

| microsomal epoxide hydrolase 1 | α1-acid glycoprotein 1 | ||||

| solute carrier family 12 member 1 (Na–Cl–K symporter, NKCC) | |||||

| calcium-activated potassium channel subunit α 1 (BK channel, BK) | |||||

| carbonic anhydrase 1/2/4 (CA1/2/4) | |||||

| calcium channel blockers | voltage-dependent L-type calcium channel subunit α1C (Cav1.2) | CYP3A4 | albumin | P-glycoprotein 1 (P-gP) | |

| CYP3A5 | |||||

| CYP2B6 | |||||

| CYP1A2 | |||||

| voltage-dependent T-type calcium channel subunit α1I (Cav3.3) | CYP2A6 | α1-acid glycoprotein | |||

| voltage-dependent L-type calcium channel subunit α1D (Cav3.3) | |||||

| voltage-dependent L-type calcium channel subunit β2 (Cav1.2b) | |||||

| ACE-I | angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) | albumin | solute carrier organic anion transporter family member 1A2 (OATP1) | solute carrier family 15-member 1 (PEPT1) | |

| renin | α1-acid glycoprotein | solute carrier family 15-member 2 (PEPT2) | |||

| ARBs | type 1 angiotensin II receptor (AT1) | CYP2C9 | albumin | solute carrier organic anion transporter family member 1B3 (OATP8) | |

| CYP3A4 | |||||

| UDP-glucuronosyl transferase 1-1 | |||||

| UDP-glucuronosyl transferase 1-3 | solute carrier organic anion transporter family member 1B1 (OATP2) | ||||

| UDP-glucuronosyl transferase 1-10 | |||||

| UDP-glucuronosyl transferase 2B7 | canalicular multispecific organic anion transporter 1 (MRP2) | ||||

| UDP-glucuronosyl transferase 2B17 | P-glycoprotein 1 (P-gp) | ||||

See Appendix I, Table S2 for a total overview.

Selected Medicinal Plants for Treating Hypertension, Their Phytochemicals, and Potential Drug Interactions with Antihypertensive Drugs

In total, 30 phytochemicals were selected from eleven (11) plants; see Table 4. Twenty-seven (27) of 30 compounds show dissociation constants below 10 μM. The experiments showed that ascorbic acid, γ-aminobutyric acid, myristicin, 6-methoxybenzoxazolinone, 4-terpinol, citral, 1,8-cineole, and elemicin scored Kd < 10 μM only with the drug class of the ARBs. All of the other compounds scored in all docking experiments with Kd values <10 μM.

Table 4. Thirty (30) Phytochemicals Selected from Eleven (11) Plantsa.

The scientific plant names and common Barbadian names for each plant, their phytochemistry, chemical structures, and the PubChem CID codes that were used to obtain the 3D structures are outlined. Also, the parts of the plant where the phytochemical is concentrated are mentioned.

Some phytochemicals show good binding affinity to various pharmacodynamic drug targets. Remarkably, oleanolic acid showed consistently very low Kd values for almost all protein targets in the docking experiments. See Tables 5–8 for a detailed overview of the results from all docking experiments.

Table 5. Molecular Docking Results of Thiazide and Thiazide-Like Diureticsa.

| pharmacodynamics |

metabolism |

distribution |

excretion | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ligand | NCC | NKCC | BK | CA1 | CA2 | CA4 | CYP3A4 | mEH | albumin | α1Glycp1 | OAT1 |

| ligand B30 (reference ligand) | 4.82 | ||||||||||

| ethoxzolamide (reference ligand) | 28.25 | ||||||||||

| methazolamide (reference ligand) | 58.46 | ||||||||||

| dorzolamide (reference ligand) | 38.40 | ||||||||||

| inhibitor PK9 (reference ligand) | 125,419 | ||||||||||

| bendroflumethiazide | 4.89 | 5.26 | 0.88 | 0.59 | 0.08 | 2.10 | 0.02 | 0.80 | 0.12 | 0.22 | 0.14 |

| chlorthalidone | 7.23 | 9.95 | 0.56 | 0.09 | 0.14 | 1.33 | 0.03 | 2.39 | 0.17 | 0.67 | 0.28 |

| indapamide | 7.26 | 6.10 | 0.48 | 0.11 | 0.80 | 5.63 | 0.03 | 1.04 | 1.07 | 0.12 | 0.57 |

| losartan | 7.27 | 3.85 | 2.99 | 0.78 | 3.22 | 0.08 | 1.49 | 1.03 | 2.86 | ||

| valsartan | 2.13 | 1.28 | 0.94 | 0.13 | 1.03 | 1.41 | 0.44 | 2.42 | |||

| nifedipine | 3.54 | 1.48 | 0.15 | 4.02 | 2.27 | 1.46 | |||||

| amlodipine | 9.13 | 0.54 | 4.14 | 3.97 | |||||||

| ramipril | 7.15 | 5.94 | 0.49 | 9.35 | 0.16 | 2.51 | 2.27 | 0.50 | 1.51 | ||

| enalapril | 2.77 | 1.57 | 7.07 | 1.21 | 6.87 | 0.41 | 0.99 | 4.46 | |||

| lisinopril | 6.20 | 3.50 | 0.87 | 2.63 | 0.89 | 1.84 | 4.08 | ||||

| mitraphylline | 7.02 | 0.87 | 0.84 | 4.01 | 0.01 | 2.45 | 0.96 | 0.07 | 0.35 | ||

| 8-hydroxytricetin 7-glucuronide | 8.02 | 2.36 | 2.32 | 0.36 | 1.30 | 1.64 | 0.03 | 0.20 | 0.08 | 1.12 | 0.75 |

| oleanolic acid | 8.36 | 8.61 | 0.44 | 0.34 | 0.02 | 5.85 | 0.0003 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.35 |

| verbascoside | 9.95 | 2.40 | 1.62 | 1.28 | 1.56 | 5.50 | 0.02 | 0.66 | 0.11 | 1.42 | 0.08 |

| rutin | 2.76 | 2.60 | 8.03 | 1.43 | 2.19 | 0.02 | 1.22 | 0.09 | 0.34 | 0.18 | |

| corilagin | 6.95 | 8.65 | 3.54 | 0.47 | 4.95 | 0.03 | 1.81 | 0.49 | 0.21 | 0.93 | |

| reserpine | 8.35 | 1.26 | 7.28 | 1.98 | 2.24 | 1.80 | 1.22 | ||||

| vincamine | 1.19 | 1.14 | 0.07 | 8.32 | 7.33 | 0.81 | 2.46 | ||||

| coreximine | 5.20 | 2.41 | 4.15 | 7.01 | 0.18 | 1.30 | 1.74 | 2.22 | 1.30 | ||

| kaempferol | 6.37 | 3.20 | 1.72 | 5.56 | 0.97 | 0.92 | 0.49 | 0.78 | 2.20 | ||

| quercitrin | 7.74 | 9.59 | 0.37 | 2.81 | 0.04 | 1.97 | 1.62 | 0.28 | 0.08 | ||

| apigenin | 8.32 | 4.54 | 1.85 | 3.77 | 0.52 | 0.93 | 0.42 | 0.79 | 2.42 | ||

| astragalin | 8.89 | 0.71 | 0.98 | 0.09 | 3.44 | 0.41 | 1.33 | 0.37 | |||

| aucubin | 2.69 | 7.26 | 7.94 | 3.39 | 6.43 | ||||||

| adenosine | 6.84 | 8.28 | 8.02 | 9.99 | |||||||

| caffeic acid | 7.44 | 6.62 | 1.42 | ||||||||

| tryptophan | 9.13 | 4.70 | 9.24 | ||||||||

| subaphyllin | 5.62 | ||||||||||

| estragole | 5.85 | ||||||||||

| α-linolenic acid | 9.13 | ||||||||||

Binding affinities are presented as dissociation constants (Kd) in μM. Dissociation constants of reference ligands of corresponding proteins and selected antihypertensive drugs are also presented.

Table 8. Molecular Docking Results of Angiotensin II Receptor Blockersa.

| pharmacodynamics | metabolism |

distribution | excretion |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ligand | AT1 | CYP2C9 | CYP3A4 | UDPGT 1-1 | UDPGT 1-3 | UDPGT 1-10 | UDPGT 2B7 | UDPGT 2B17 | albumin | OATP2 | OATP8 | MRP2 | P-gp |

| olmesartan (reference ligand) | 1.10 | ||||||||||||

| flurbiprofen (reference ligand) | 0.33 | ||||||||||||

| bendroflumethiazide | 0.15 | 0.12 | 0.02 | 0.19 | 0.12 | 0.63 | 0.48 | 0.19 | 0.12 | 0.16 | 0.38 | 0.08 | 0.12 |

| chlorthalidone | 0.35 | 0.23 | 0.03 | 0.21 | 0.53 | 0.38 | 0.50 | 0.08 | 0.17 | 1.11 | 1.14 | 0.36 | 0.38 |

| indapamide | 0.11 | 0.19 | 0.03 | 0.36 | 0.53 | 0.55 | 0.14 | 0.23 | 1.07 | 0.75 | 0.77 | 0.20 | 0.25 |

| losartan | 0.16 | 0.30 | 0.08 | 0.55 | 0.38 | 0.63 | 1.01 | 0.09 | 1.23 | 0.48 | 0.31 | 0.24 | |

| valsartan | 0.17 | 1.06 | 0.13 | 0.70 | 0.22 | 1.93 | 0.87 | 0.35 | 1.41 | 6.14 | 0.47 | 1.66 | |

| nifedipine | 2.75 | 0.20 | 0.15 | 3.51 | 0.67 | 2.82 | 4.02 | 2.92 | 4.65 | 1.22 | 3.32 | ||

| amlodipine | 3.47 | 1.80 | 0.54 | 4.02 | 6.43 | 7.09 | 4.58 | 8.71 | 3.99 | 3.47 | 7.60 | ||

| ramipril | 0.84 | 0.33 | 0.16 | 0.54 | 3.32 | 0.83 | 2.81 | 2.06 | 2.27 | 2.03 | 2.76 | 0.80 | 1.73 |

| enalapril | 2.49 | 0.86 | 1.21 | 1.79 | 5.23 | 2.77 | 3.58 | 1.56 | 0.41 | 9.51 | 6.19 | 1.85 | 2.43 |

| lisinopril | 2.02 | 1.79 | 0.87 | 4.82 | 4.91 | 8.83 | 3.79 | 2.50 | 0.89 | 4.04 | 8.56 | ||

| mitraphylline | 0.06 | 4.19 | 0.01 | 0.35 | 0.65 | 0.53 | 0.69 | 0.85 | 0.96 | 0.50 | 0.52 | 0.22 | 0.65 |

| 8-hydroxytricetin 7-glucuronide | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.10 | 0.05 | 0.13 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.48 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.19 |

| oleanolic acid | 0.04 | 3 × 10–3 | 0.13 | 0.01 | 0.07 | 5.47 | 0.17 | 0.04 | 0.13 | 0.44 | 0.02 | 0.11 | |

| verbascoside | 0.11 | 0.89 | 0.02 | 0.36 | 0.10 | 0.58 | 0.50 | 0.25 | 0.11 | 0.63 | 0.52 | 0.19 | 0.42 |

| rutin | 0.21 | 0.07 | 0.02 | 0.23 | 0.06 | 0.45 | 1.58 | 0.56 | 0.09 | 0.43 | 0.25 | 0.04 | 0.40 |

| corilagin | 0.09 | 0.03 | 1.62 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 8.41 | 0.49 | 0.08 | 0.70 | 0.06 | 0.24 | ||

| reserpine | 0.12 | 1.98 | 0.25 | 0.06 | 0.53 | 7.56 | 0.82 | 1.80 | 0.79 | 1.25 | 0.11 | 0.38 | |

| vincamine | 0.33 | 0.68 | 0.07 | 0.36 | 0.71 | 0.67 | 4.06 | 5.66 | 7.33 | 1.92 | 0.69 | 0.60 | 1.06 |

| coreximine | 0.77 | 1.77 | 0.18 | 1.22 | 0.58 | 1.27 | 0.44 | 1.01 | 1.74 | 5.62 | 2.47 | 1.37 | 1.85 |

| kaempferol | 0.97 | 0.73 | 0.97 | 0.78 | 1.59 | 1.50 | 2.10 | 2.48 | 0.49 | 4.59 | 1.48 | 1.46 | 2.49 |

| quercitrin | 0.59 | 0.17 | 0.04 | 0.39 | 0.57 | 0.66 | 0.29 | 1.57 | 1.62 | 0.78 | 0.32 | 0.78 | 0.56 |

| apigenin | 1.02 | 0.44 | 0.52 | 1.38 | 0.86 | 1.09 | 1.34 | 1.55 | 0.42 | 2.83 | 1.51 | 0.85 | 1.64 |

| astragalin | 0.43 | 0.20 | 0.09 | 0.50 | 0.46 | 1.20 | 2.24 | 1.62 | 0.41 | 2.45 | 0.40 | 0.95 | 1.33 |

| aucubin | 6.33 | 3.22 | 2.69 | 5.09 | 4.47 | 6.75 | 5.16 | 6.78 | 7.94 | 3.75 | 8.20 | ||

| adenosine | 7.90 | 8.28 | 8.18 | 5.62 | 5.75 | 9.15 | 9.99 | ||||||

| caffeic acid | 6.62 | 1.42 | |||||||||||

| tryptophan | 6.74 | 5.19 | 4.70 | 5.93 | 7.53 | ||||||||

| subaphyllin | 7.71 | 5.62 | |||||||||||

| estragole | 5.85 | ||||||||||||

| α-linolenic acid | 6.30 | 9.02 | |||||||||||

Binding affinities are presented as dissociation constants (Kd) in μM. Dissociation constants of reference ligands of corresponding proteins and selected antihypertensive drugs are also presented.

Table 7. Molecular Docking Results of Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitorsa.

| pharmacodynamics |

distribution |

absorption |

excretion | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ligand | ACE | renin | albumin | α1GlycP1 | PEPT1 | PEPT2 | OATP1 |

| lisinopril (reference ligand) | 0.66 | ||||||

| ligand X (reference ligand) | 0.04 | ||||||

| bendroflumethiazide | 0.07 | 0.13 | 0.12 | 0.22 | 0.11 | 0.87 | 0.31 |

| chlorthalidone | 0.47 | 0.10 | 0.17 | 0.67 | 0.45 | 0.46 | 0.40 |

| indapamide | 0.14 | 0.37 | 1.07 | 0.12 | 0.33 | 0.07 | 0.34 |

| losartan | 0.19 | 1.51 | 1.03 | 0.31 | 0.65 | 0.93 | |

| valsartan | 0.31 | 3.53 | 1.41 | 0.44 | 0.31 | 0.23 | 0.76 |

| nifedipine | 0.83 | 0.98 | 4.02 | 2.27 | 1.55 | 2.15 | 4.90 |

| amlodipine | 1.44 | 1.50 | 4.14 | 4.46 | 7.79 | ||

| ramipril | 0.41 | 1.49 | 2.27 | 0.50 | 0.99 | 0.36 | 0.70 |

| enalapril | 1.17 | 2.14 | 0.41 | 0.99 | 4.53 | 0.56 | 3.45 |

| lisinopril | 1.43 | 1.69 | 0.89 | 1.84 | 2.67 | 1.72 | 4.62 |

| mitraphylline | 0.17 | 0.10 | 0.96 | 0.07 | 0.22 | 2.02 | 0.19 |

| 8-hydroxytricetin 7-glucuronide | 0.06 | 0.26 | 0.08 | 1.12 | 0.12 | 0.05 | 0.15 |

| oleanolic acid | 0.13 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 0.50 | 0.09 |

| verbascoside | 0.18 | 0.41 | 0.11 | 1.42 | 0.15 | 3.29 | 0.01 |

| rutin | 0.10 | 0.35 | 0.09 | 0.34 | 0.56 | 0.05 | 0.08 |

| corilagin | 0.02 | 0.35 | 0.49 | 0.21 | 0.04 | 1.45 | 0.53 |

| reserpine | 2.00 | 0.49 | 1.80 | 2.98 | 0.21 | ||

| vincamine | 0.39 | 0.09 | 7.33 | 0.81 | 1.53 | 3.85 | 0.78 |

| coreximine | 0.68 | 4.82 | 1.74 | 2.22 | 1.03 | 0.31 | 1.31 |

| kaempferol | 1.28 | 4.83 | 0.49 | 0.78 | 1.56 | 1.01 | 2.48 |

| quercitrin | 0.20 | 0.54 | 1.62 | 0.28 | 0.43 | 0.78 | 0.45 |

| apigenin | 1.38 | 4.21 | 0.42 | 0.79 | 1.43 | 0.58 | 1.87 |

| astragalin | 0.23 | 0.96 | 0.41 | 1.33 | 0.63 | 4.70 | 0.82 |

| aucubin | 1.42 | 4.18 | 7.94 | 3.39 | 7.81 | 1.33 | |

| adenosine | 6.69 | 9.99 | 9.67 | 3.79 | |||

| caffeic acid | 1.42 | 8.83 | |||||

| tryptophan | 9.54 | 5.80 | 9.24 | ||||

| subaphyllin | 8.70 | 9.54 | 4.59 | ||||

| estragole | 5.85 | ||||||

| α-linolenic acid | 8.09 | 9.13 | 8.32 | ||||

Binding affinities are presented as dissociation constants (Kd) in μM. Dissociation constants of reference ligands of corresponding proteins and selected antihypertensive drugs are also presented.

Discussion

The exact mechanism of action of many drug–herb interactions is unknown, and hence their related adverse drug reactions are complex to manage.1 Here in this study, 30 phytochemicals from 11 popular medicinal plants in Barbados were screened to determine potential drug–herb interactions with the most prescribed antihypertensive drugs in Barbados. The prevalence of hypertension in Barbados in 45–64 and 65 and over age categories was reported at 52.9 (47.4, 58.3) and 78.2 (71.8, 83.5) at the 95% CI in 2015.37 These age groups represent the elderly population in Barbados who practice the use of herbal medicines more extensively to manage their illnesses.

Drug interactions can bring about beneficial and adverse drug reaction (toxicity)-related outcomes. Some of these effects are well defined and established in the medical literature. However, drug interactions that are not well defined can bring about uncertainty in eliciting the therapeutic effect of either drug or substance administered concomitantly. Below, the findings of the molecular docking experiments are interrogated for a more comprehensive understanding of these potential drug–herb interactions.

Thiazide and Thiazide-Like Diuretics

Oleanolic acid is known from the literature as a diuretic;32 see Appendix III, Table S6. Results show that the dissociation constants of oleanolic acid for NCC and NKCC targets are 8.36 and 8.61 μM, respectively. There is a possibility that it can block NCC/NKCC and can also cause diuresis. Also, mitraphylline (7.02 μM) and 8-hydroxytricetin-7-glucuronide (2.36 μM) show good binding affinity to NCC. Another protein involved in decreasing blood pressure is the BK channel, which controls smooth muscle contractions. Deficiencies in the expression of this channel are related to hypertension.28,38 Mitraphylline is known from the literature as a vasodilator;32 see Appendix III for more details. The Kd of mitraphylline for the BK channel is 0.87 μM. It is possible that the vasodilatory effect of mitraphylline may be related to its interaction with the BK channel.

Herbal preparations with compounds like oleanolic acid and mitraphylline in combination with these antihypertensive drugs may cause (orthostatic) hypotension, resulting in syncope episodes, especially among the elderly who are vulnerable to this type of outcome. Therefore, a potential clinically significant issue could arise from the coadministration of drugs and herbs with these compounds (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic overview of the workflow.

Most of the thiazide and thiazide-like diuretics are excreted by OAT1, OAT3, and MRP2 in the proximal tubules of the kidneys.12,15 Mice lacking one of these membrane proteins are resistant to thiazide and loop diuretics.39 Verbascoside and rutin show relatively high binding affinities to OAT1, i.e., 0.08 μM (see Figure 2) and 0.18 μM, respectively. If these two are inhibitors, the pharmacological action of thiazide diuretics may be reduced, and the elimination half-life can be prolonged. Bendroflumethiazide is an exception to this; it is highly metabolized to unknown metabolites and excreted by the kidneys. It is not known if its metabolites can interface with these excretion channels in the proximal tubules. In vitro studies are needed for confirmatory purposes.

Figure 2.

Verbascoside (pink) in the channel of OAT1. Inhibition of OAT1 could affect the excretion of thiazide-like diuretics and many other drugs.

Moreover, the BK channel is involved in not only vasodilatation but also the regulation of neurotransmitter release and hormone secretion. High binding affinities of compounds to this BK channel can lead to potentially active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) candidates for psychiatric disorders or epilepsy.38 Compounds with a high binding affinity to carbonic anhydrase 2 with a possible inhibitory effect are also potential candidates for treating glaucoma due to lowering the fluid pressure in the eye chamber.28

Calcium Channel Blockers

Oleanolic acid was the only compound that binds to the dihydropyridine (DHP) binding site of Cav1.2 (2.78 μM). It is also one of the few compounds that bind to the β subunit of Cav1.2, with the highest binding affinity (0.23 μM). Oleanolic acid shows good binding affinities to L-Cav1.3 and T-Cav3.3. Other compounds that bind to the Cav1.2 β subunit are aucubin, kaempferol, vincamine, rutin, and 8-hydroxytricetin 7-glucuronide. The β subunit of the drug target is potentially interesting because this subunit controls the activity of the α1 subunit.28 Quite noteworthy, the binding affinity of various phytochemicals is better on the dihydropyridine binding site than on the phenylalkylamine (PAA) site.

Reserpine is known in the literature as a calcium channel antagonist;32 its binding affinities are among the highest to almost all calcium channel (parts): Cav1.2-PAA (0.27 μM), Cav1.3-DHP (3.82 μM), Cav1.3-PAA (0.54 μM), and T-Cav3.3 (0.95 μM). Apigenin is also known as a calcium channel antagonist,32 with good binding affinities to these proteins. So, it is plausible that reserpine and apigenin can block calcium channels and cause vasodilatation but can also affect the heart rate since they bind to the PAA site.

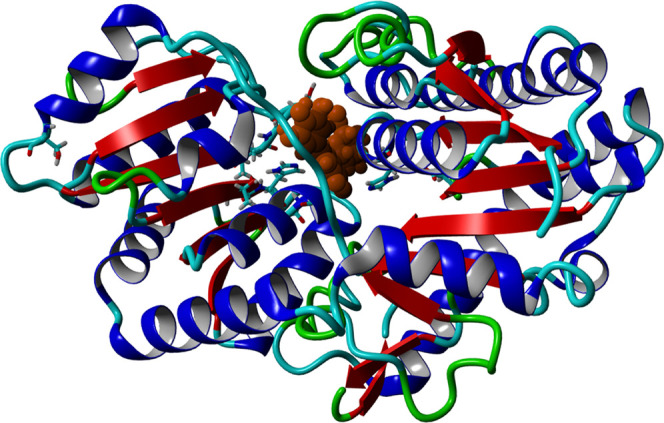

Dihydropyridines are metabolized by hepatic CYP enzymes. For example, nifedipine is metabolized by CYP3A4. Various compounds show good binding affinities to CYP3A4, especially oleanolic acid, which has a high affinity (0.003 μM); see Figure 3. If this binding results in inhibition, it can reduce the metabolism of the drug and increase the plasma concentration of nifedipine. This risk is particularly higher in the elderly and patients with liver dysfunction.

Figure 3.

Oleanolic acid (violet) in the binding pocket of CYP3A4, close to the heme cofactor. Inhibition of CYP3A4 could increase the plasma concentration of nifedipine and increase the risk of serious side effects (hypotension with tachycardia).

This increases the incidence of side effects such as hypotension, dizziness, reflex tachycardia, and more serious ailments such as cardiac rhythm disruption, which are already more pronounced in nifedipine than other dihydropyridine CCBs.

P-gp is known as an efflux protein and has a role in the excretion of dihydropyridines and other drugs. Reserpine is known as a P-gp inhibitor;40 this means that the efflux of drugs from cells can be halted. Kd of reserpine for P-gp is 0.38 μM. Other phytochemicals such as verbascoside, rutin, quercitrin, and corilagin show good binding affinities to the P-gp.

These interactions can potentially be considered therapeutic enhancers of drugs that are subjected to high efflux. From a view of drug discovery, inhibitors of T-type Cav3.3 could be API candidates for treating epilepsy, psychiatric disorders, and neuropathic pain.41

Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitors

Quercitrin, astragalin, and corilagin are known as ACE inhibitors from in vitro studies;32 see Appendix III, Table 6. In this study, high binding affinities of these compounds to ACE were found: 0.20, 0.23, and 0.02 μM, respectively. Also, their binding affinities for renin and pharmacokinetic target proteins such as PEPT1, PEPT2, and OATP1 are high (Kd < 1 μM).

Table 6. Molecular Docking Results of Dihydropyridine Calcium Channel Blockersa.

| pharmacodynamics |

metabolism |

distribution |

excretion | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cav1.2 | Cav1.2β | Cav1.3 | ||||||||||||

| ligand | DHP | PAA | DHP | PAA | Cav3.3 | CYP1A2 | CYP2A6 | CYP2B6 | CYP3A4 | CYP3A5 | albumin | α1Glycp1 | P-gp | |

| α-naphthoflavone (reference ligand) | 2 × 10–4 | |||||||||||||

| ligand X1 (reference ligand) | 4.48 | |||||||||||||

| ligand X2 (reference ligand) | 41.36 | |||||||||||||

| inhibitor PK9 (reference ligand) | 1.2 × 105 | |||||||||||||

| ritonavir (reference ligand) | 0.09 | |||||||||||||

| vincristine (reference ligand) | 0.01 | |||||||||||||

| bendroflumethiazide | 0.62 | 7.31 | 2.21 | 0.8 | 0.13 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.12 | 0.22 | 0.12 | ||||

| chlorthalidone | 1.42 | 3.12 | 2.95 | 1.71 | 0.44 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.11 | 0.17 | 0.67 | 0.38 | |||

| indapamide | 8.02 | 0.42 | 1.52 | 0.83 | 0.78 | 0.75 | 2.23 | 0.03 | 0.09 | 1.07 | 0.12 | 0.25 | ||

| losartan | 0.79 | 9.69 | 0.59 | 0.36 | 0.08 | 0.19 | 1.03 | 0.24 | ||||||

| valsartan | 5.65 | 4.14 | 1.41 | 0.13 | 0.27 | 1.41 | 0.44 | 1.66 | ||||||

| nifedipine | 132.83* | 4.21 | 169.02* | 2.02 | 2.25 | 0.15 | 1.08 | 4.02 | 2.27 | 3.32 | ||||

| amlodipine | 184.91* | 15.70* | 28.53* | 11.41* | 7.57 | 0.54 | 4.30 | 4.14 | 7.60 | |||||

| ramipril | 1.42 | 1.53 | 3.28 | 0.85 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 2.27 | 0.50 | 1.73 | |||||

| enalapril | 2.17 | 5.80 | 5.16 | 2.45 | 0.67 | 1.21 | 0.71 | 0.41 | 0.99 | 2.43 | ||||

| lisinopril | 3.72 | 9.41 | 3.10 | 0.87 | 1.51 | 0.89 | 1.84 | 8.56 | ||||||

| mitraphylline | 0.60 | 1.52 | 0.77 | 0.13 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.96 | 0.07 | 0.65 | |||||

| 8-hydroxytricetin 7-glucuronide | 0.45 | 8.06 | 2.74 | 0.26 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.18 | 0.08 | 1.12 | 0.19 | ||||

| oleanolic acid | 2.78 | 0.05 | 0.23 | 0.23 | 0.04 | 0.17 | 3 × 10–3 | 29 × 10–2 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.11 | |||

| verbascoside | 0.36 | 0.13 | 0.11 | 0.02 | 0.30 | 0.11 | 1.42 | 0.42 | ||||||

| rutin | 0.14 | 7.98 | 4.08 | 0.20 | 0.25 | 0.02 | 0.18 | 0.09 | 0.34 | 0.40 | ||||

| corilagin | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.15 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.49 | 0.21 | 0.24 | ||||||

| reserpine | 0.27 | 3.82 | 0.54 | 0.95 | 1.98 | 1.80 | 0.38 | |||||||

| vincamine | 2.46 | 3.28 | 4.35 | 1.59 | 1.82 | 0.07 | 0.21 | 7.33 | 0.81 | 1.06 | ||||

| coreximine | 3.11 | 3.83 | 3.71 | 1.84 | 0.18 | 0.59 | 1.74 | 2.22 | 1.85 | |||||

| kaempferol | 2.93 | 7.50 | 2.68 | 3.00 | 2.95 | 0.01 | 0.97 | 2.11 | 0.49 | 0.78 | 2.49 | |||

| quercitrin | 0.87 | 0.97 | 0.04 | 0.70 | 1.62 | 0.28 | 0.56 | |||||||

| apigenin | 2.96 | 5.57 | 2.84 | 2.67 | 0.01 | 0.52 | 1.27 | 0.42 | 0.79 | 1.64 | ||||

| astragalin | 2.15 | 1.65 | 0.94 | 0.09 | 0.61 | 0.41 | 1.33 | 1.33 | ||||||

| aucubin | 6.07 | 8.86 | 5.38 | 2.68 | 2.69 | 4.14 | 7.94 | 3.39 | 8.20 | |||||

| adenosine | 2.78 | 1.59 | 8.28 | 9.99 | ||||||||||

| caffeic acid | 0.83 | 5.70 | 6.62 | 9.27 | 1.42 | |||||||||

| tryptophan | 0.41 | 0.50 | 3.14 | 4.70 | 3.95 | 9.24 | ||||||||

| citral | 2.23 | 2.96 | ||||||||||||

| myristicin | 1.05 | 5.92 | 6.55 | |||||||||||

| 1,8-cineole | 3.48 | 6.84 | ||||||||||||

| subaphyllin | 8.13 | 1.79 | 5.62 | |||||||||||

| terpineol | 2.90 | 1.52 | 6.12 | |||||||||||

| estragole | 2.82 | 5.85 | ||||||||||||

| α-linolenic acid | 6.97 | 7.27 | 0.25 | 5.64 | 2.28 | 9.13 | ||||||||

| 6-methoxybenzoxazolinone | 2.42 | 7.10 | ||||||||||||

| eugenol | 1.63 | 9.04 | ||||||||||||

| elemicin | 2.41 | |||||||||||||

Binding affinities are presented as dissociation constants (Kd) in μM. Dissociation constants of reference ligands of corresponding proteins and selected antihypertensive drugs are also presented. Amlodipine and nifedipine showed relatively high Kd’s for dihydropyridine (DHP) binding target Cav1.2 and phenylalkylamine (PAA) binding sites Cav1.2 β and Cav1.3. These are indicated with an asterisk (*).

Since compounds like quercitrin, astragalin, and corilagin bind in the binding pocket of ACE and renin, they can possibly inhibit these enzymes competitively and are potential drug candidates. PEPT1 has a key role in the absorption of many drugs such as ACE inhibitors, antiviral drugs, and β-lactam antibiotics.42 PEPT2 is more responsible for the bioavailability of drugs in the brain.42 Oleanolic acid shows high binding affinities to PEPT1 (see Figure 4) (0.01 μM) and PEPT2 (0.50 μM). Potential inhibitors of PEPT1 can lower the bioavailability of ACE inhibitors and other drugs, resulting in low plasma levels and subtherapeutic effects. Drugs with a low bioavailability in the central nervous system may benefit from PEPT2 inhibitors, which are potential pharmacotherapeutic enhancers. OATP1 has a role in the excretion of many drugs, inclusive of ACE inhibitors. It is known that naringin can inhibit OATP1, so it is likely that other similar flavonoids with high binding affinity for OATP1 are potential inhibitors. Astragalin, rutin, and quercitrin (see Figure 5) have high binding affinities to this target (Kd < 1 μM). Rutin’s binding affinity is below 0.1 μM. This can result in higher plasma concentrations and potential side effects such as orthostatic hypotension, hyperkalemia, and renal impairment. There is also a possibility of accumulation of enalaprilat in patients with a renal clearance of <30 mL/min (Table 9).

Figure 4.

Oleanolic acid in the central cavity of PEPT1. PEPT1 is involved in the absorption of ACE-I, β-lactam antibiotics, HIV inhibitors, and many other drugs. Inhibition of PEPT1 could affect the absorption and bioavailability of many drugs.

Figure 5.

Rutin (green) and quercitrin (yellow), two flavonoids, in the central pore of OATP1. Grapefruit juice contains naringin, also a flavonoid, which is known as a potent OATP1 inhibitor. Likely, rutin, quercitrin, and similar flavonoids could probably also inhibit OATP1.

Table 9. Phytochemicals with High Binding Affinities (Kd Values < 10 μM) to the Pharmacological Targets of the Antihypertensive Drugs.

| phytochemical | plant name (botanical and common names) |

|---|---|

| mitraphylline | Catharanthus roseus (L.) G. Don (Madagascar Periwinkle) |

| oleanolic acid | C. roseus (L.) G. Don (Madagascar Periwinkle) |

| reserpine | C. roseus (L.) G. Don (Madagascar Periwinkle) |

| vincamine | C. roseus (L.) G. Don (Madagascar Periwinkle) |

| adenosine | C. roseus (L.) G. Don (Madagascar Periwinkle) |

| quercitrin | Phyllanthus niruri L. (Seed under Leaf) |

| astragalin | P. niruri L. (Seed under Leaf) |

| corilagin | P. niruri L. (Seed under Leaf) |

| Terminalia catappa L. (Barbados almond) | |

| rutin | P. niruri L. (Seed under Leaf) |

| Petroselinum crispum (Mill.) Fuss (Parsley) | |

| kaempferol | P. crispum (Mill.) Fuss (Parsley) |

| T. catappa L. (Barbados almond) | |

| apigenin | P. crispum (Mill.) Fuss (Parsley) |

| elemicin | P. crispum (Mill.) Fuss (Parsley) |

| myristicin | P. crispum (Mill.) Fuss (Parsley) |

| estragole | P. crispum (Mill.) Fuss (Parsley) |

| Pimenta racemosa Mill (Bay leaf) | |

| caffeic acid | P. crispum (Mill.) Fuss (Parsley) |

| Plantago major L (English plantain) | |

| Annona muricata L (Soursop) | |

| Carica papaya L. (Papaya) | |

| citral | P. racemosa (Mill.) J.W. Moore |

| 1,8-cineole | P. racemosa (Mill.) J.W. Moore |

| eugenol | P. racemosa (Mill.) J.W. Moore |

| 4-terpinol | P. racemosa (Mill.) J.W. Moore |

| P. crispum (Mill.) Fuss (Parsley) | |

| C. papaya L. (Papaya) | |

| aucubin | P. major L (English plantain) |

| tryptophan | A. muricata L. (Soursop) |

| C. papaya L. (Papaya) | |

| Persea americana Mill (Pear) | |

| α-linolenic acid | C. papaya L. (Papaya) |

| coreximine | A. muricata L. (Soursop) |

| subaphyllin | P. americana Mill (Pear) |

| 8-hydroxytricetin-7-glucuronide | Lantana involucrata L. (Rock sage) |

| 6-methoxybenzoxazolinone | L. involucrata L. (Rock sage) |

| verbascoside | Momordica charantia L (Lizard food) |

Extra attention must be shown to elderly patients with a heightened risk of renal artery stenosis and patients using loop diuretics. The chance for toxicity is more plausible for ACE inhibitors, which contain a sulfhydryl group, such as captopril.

Angiotensin Receptor Blockers

Various phytochemicals showed high binding affinities (Kd < 0.1 μM) for AT1R such as mitraphylline, oleanolic acid, corilagin, and 8-hydroxytricetin 7-glucuronide. Some ARBs are metabolized to more potent active metabolites, such as the active metabolite EXP317 from losartan. CYP enzymes are involved in this biotransformation; potential CYP3A4 and CYP2C9 inhibitors such as reserpine can decrease the AUC for these active metabolites, thus countering the pharmacological action of metabolites.

Other ARBs are not metabolized by CYP enzymes, such as valsartan. UDP-glucuronosyltransferases are more involved in the metabolism of valsartan. In this study, relatively high binding affinities of 8-hydroxytricetin 7-glucuronide to the UDPG transferases are seen with Kd < 0.1 μM (Figure 6). Also, other compounds like verbascoside and quercitrin show high binding affinities to UDPG transferases (Kd values < 0.1 μM). Inhibiting UDPG transferases can increase the AUC of valsartan or other related compounds, resulting in potentiated effects with the possibility of more side effects: hypotension, hyperkalemia, and renal impairment.

Figure 6.

8-Hydroxytricetin 7-glucuronide in the binding pocket of UDP-G transferase B7. Inhibition can influence the phase II metabolism of some ARBs.

Excretion and the plasma concentration of ARBs can be affected by inhibiting OATP2, OATP8, MRP2, and P-gp. Quercitrin, mitraphylline, rutin, corilagin, verbascoside, oleanolic acid, reserpine, and 8-hydroxytricetin 7-glucuronide had high binding affinities to these proteins (Kd values < 1 μM). Attention must be paid to patients with liver dysfunction, such as cirrhosis and the elderly since the hepatic blood flow and first-pass effect are reduced.

Limitations

In this study, an assumption that dissociation constant below 10 μM represented moderate to high binding affinities was made and therefore compounds with dissociation constants within this range on binding to the pharmacological targets could be considered as potential ligands in vitro or in vivo. Docking experiments with reference ligands showed interesting findings. For example, the carbonic anhydrase inhibitors (e.g., dorzolamide) vary between 4.82 and 38.40 μM. Also, amlodipine and nifedipine showed unexpected Kd values for their targets. The Kd of nifedipine and amlodipine to its dihydropyridine binding site (Cav1.2) was 132.83 and 184.9 μM, respectively. This was the same for the β-subunit of the calcium channel. The QMEANDisCo scores for these proteins are above 0.6, and the simulation cell was set correctly, so it was concluded that binding affinities in the range between 10 and 200 μM could also be considered for potential binding ligands.

It is likely that potential interactions with phytochemicals and specific target proteins with dissociation constants above 10 μM were not noted based on our methodology. However, all other antihypertensive drugs show dissociation constants for their intended targets below 10 μM, as expected. Moreover, some antihypertensive drugs also bind to other drug targets with high binding affinities.

Thirty (30) phytochemicals with reported antihypertensive effects were selected for analysis. However, compounds without a known antihypertensive effect were not selected, and maybe these compounds in the plants could cause drug interactions. The concentration of the bioactive compounds in various parts of the plants used is difficult to determine due to issues related to the standardization of herbal practices. For example, the Madagascar periwinkle is used as a decoction of the leaves, but it can be assumed that some individuals will use varying amounts of the specific recommended plant part and other parts of the plant in their herbal preparations. Most of the plant preparations are boiled, and it is possible that some compounds will degenerate and lose their assumed bioactivity. Another important point is that some compounds are present in nature as stereoisomers (e.g., enantiomers). Enantiomers are known to have variations in potencies, which may be related to different binding affinities and efficacy.

These differences will affect the docking experiments in Yasara. The quality of the 3D protein structure will also affect the docking precision; the QMEANDisCo scores of OAT1, UDPG transferases, and Cav3.3 are below 0.6, so docking results of these proteins must be reviewed critically.

Finally, although this study contains limitations, these in silico experiments provide a good screening tool for identifying potential drug–herb interactions. It is recommended that docking of phytochemicals with respective drug targets must be explored in vitro and in vivo to confirm the clinical significance of the findings. These results must be interpreted carefully, and no definitive conclusion can be made, since this in silico study is limited only to molecular docking. This work can be seen as a preselection of potential compounds for further studies and create awareness among doctors and pharmacists, especially in the Caribbean region.

Conclusions

Molecular docking was used to determine the binding affinities of 30 selected phytochemicals from 11 Barbadian medicinal plants to protein targets involved in the pharmacology of the most prescribed antihypertensive drugs in Barbados. Results show that 27 of 30 compounds show potential binding affinities and are likely to cause drug interactions. The following plants C. roseus (L.) G. Don (Madagascar periwinkle), P. niruri L. (Seed under leaf), P. crispum Mill. Fuss (Parsley), and L. involucrata L. (Rock sage) are potential herbs that could cause a drug–herb interaction with thiazide and thiazide-like diuretics (bendroflumethiazide, indapamide, chlorthalidone, natrixam), calcium channel blockers (amlodipine, nifedipine), ACE-I (enalapril, lisinopril, ramipril), and ARBs (valsartan, losartan). Important interactions that could affect the pharmacology are related to the excretion and pharmacodynamics of thiazides, metabolism of calcium channel blockers, absorption of ACE-I, and metabolism and excretion of ARBs. Oleanolic acid shows a high binding affinity to all target proteins in all experiments. Attention to the following specific patient groups should be considered: elderly, patients with renal failure, patients with liver disorders, and patients using loop diuretics. Further in vitro and in vivo studies are needed to clarify the specific pharmacological mechanism and determine the clinical relevance of these interactions. Compounds that are similar to naringin (e.g., astragalin, rutin, and quercitrin) and compounds that bind to OATP1, PEPT1/2, and enzymes involved in the metabolism of CCBs may be clinically relevant for further research. At the same time, compounds with high binding affinities to the BK channel, T-type Cav3.3, and PEPT2 are interesting drug candidates for epilepsy, psychiatric disorders, neuropathic pain, and enhancing drug therapy.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. E.E. Moret (Utrecht University) for technical assistance.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.2c02446.

Overview of all proteins that could be involved in the pharmacology of the selected antihypertensive drugs (bendroflumethiazide, indapamide, chlorthalidone, amlodipine, nifedipine, enalapril, lisinopril, ramipril, valsartan, and losartan); for each protein, the known “pharmacological action” and UniProtID are presented (Table S1); overview of all potential binding proteins with the corresponding UniProtID and 3D structures of the protein that was used for the molecular docking; for each protein 3D structure, the structure quality is given; human homology models (HMs) are represented by GMQE and QMEANDisCo scores, whereby a QMEANDisCo score > 0.6 is of sufficient quality; for chemical structures that are obtained from the PDB database, the resolution in Å is given, whereby a resolution <2.0 Å has a good quality; 3D structures with a bound ligand are represented with “+L”; for each protein, the characteristics of the protein, its physiological function, and information about the setup of the simulation cell are given (Table S2); overview of medicinal plants that are used in Barbados for high blood pressure with the common Barbadian name, scientific name, phytochemical (based on Dr. Duke’s Phytochemical Database), the relative concentration of the phytochemical, and known activity from the literature with the corresponding reference (Table S3); full scientific name sand most known abbreviated names of the selected proteins (Table S4); and overview of medicinal plants that are used in Barbados for high blood pressure, represented with the common Barbadian common name, scientific name, and the local preparation of the plant that is used (Table S5) (PDF)

Author Contributions

The manuscript was written by Andraniek Evadgian and reviewed by Damian Cohall (damian.cohall@cavehill.uwi.edu) and Ambadasu Bharatha (ambadasu.bharatha@cavehill.uwi.edu).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Cohall D.Medicinal Plants of Barbados: For the Treatment of Communicable and Non-Communicable Diseases; The University of the West Indies Press, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Vujicic T.; Cohall D. Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices on the Use of Botanical Medicines in a Rural Caribbean Territory. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 1–20. 10.3389/fphar.2021.713855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoel R. W.; Giddings Connolly R. M.; Takahashi P. Y. Polypharmacy Management in Older Patients. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2021, 96, 242–256. 10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhadra R.; Ravakhah K.; Ghosh R. K. Herb-Drug Interaction: The Importance of Communicating with Primary Care Physicians. Aust. J. Med. Sci. 2015, 8, 315–319. 10.4066/AMJ.2015.2479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tunstall-Pedoe H.; Kuulasmaa K.; Tolonen H.; Davidson M.; Mendis S.. et al. MONICA Monograph and Multimedia Sourcebook: World’s Largest Study of Heart Disease, Stroke, Risk Factors, and Population Trends 1979-2002; World Health Organization, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hennis A.; Wu S.; Nemesure L. M.; Leske M. C. Hypertension Prevalence, Control and Survivorship in an Afro-Caribbean Population. J. Hypertension 2002, 20, 2363–2369. 10.1097/00004872-200212000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howitt C.; Hambleton I. R.; Rose A. M. C.; Hennis A.; Samuels T. A.; George K. S.; Unwin N. Social Distribution of Diabetes, Hypertension and Related Risk Factors in Barbados: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e008869 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caribbean Health Research Council . Managing Hypertension in Primary Care in the Caribbean; Caribbean Health Research Council: Trinidad and Tobago, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Adams O. P.; Carter O. A. Are Primary Care Practitioners in Barbados Following Hypertension Guidelines?—A Chart Audit. BMC Res Notes 2010, 3, 2363 10.1186/1756-0500-3-316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurent S. Antihypertensive Drugs. Pharmacol. Res. 2017, 124, 116–125. 10.1016/j.phrs.2017.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Q.; Xu L.; Cai J. New Drug Targets for Hypertension: A Literature Review. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Mol. Basis Dis. 2021, 1867, 166037 10.1016/j.bbadis.2020.166037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rang H. P.; Ritter J. M.; Flower R. J.. Pharmacology, 8th ed.; Elsevier, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Samuels M. A.; Seifter J. L. Encephalopathies Caused by Electrolyte Disorders. Semin. Neurol. 2011, 31, 135–138. 10.1055/s-0031-1277983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez J. V.; Carrillo-Pérez D. L.; Rosado-Canto R.; García-Juárez I.; Torre A.; Kershenobich D.; Carrillo-Maravilla E. Electrolyte and Acid–Base Disturbances in End-Stage Liver Disease: A Physiopathological Approach. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2017, 62, 1855–1871. 10.1007/s10620-017-4597-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welling G. Pharmacokinetics of the Thiazides Diuretics. Biopharm. Drug Dispos. 1986, 7, 501–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opie L. H. Calcium Channel Antagonists: Part VI: Clinical Pharmacokinetics of First and Second-Generation Agents. Cardiovasc. Drugs Ther. 1989, 3, 482–497. 10.1007/BF01865507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DrugBank, 2022. https://go.drugbank.com.

- Nelson E. B.; Pool J. L.; Taylor A. A. Pharmacology of Angiotensin Converting Enzyme Inhibitors: A Review. Am. J. Med. 1986, 81, 13–18. 10.1016/0002-9343(86)90939-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israili Z. H. Clinical Pharmacokinetics of Angiotensin II (AT1) Receptor Blockers in Hypertension. J. Hum. Hypertens. 2000, 14, S73–S86. 10.1038/sj.jhh.1000991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey P.; Singhal D.; Khan F.; Arif M. An in Silico Screening on Piper Nigrum, Syzygium Aromaticum and Zingiber Officinale Roscoe Derived Compounds against Sars-cov-2: A Drug Repurposing Approach. Biointerface Res. Appl. Chem. 2021, 11, 11122–11134. 10.33263/BRIAC114.1112211134. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mooiman K. D.; Maas-Bakker R. F.; Moret E. E.; Beijnen J. H.; Schellens J. H. M.; Meijerman I. Milk Thistle’s Active Components Silybin and Isosilybin: Novel Inhibitors of Pxr-Mediated Cyp3a4 Induction. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2013, 41, 1494–1504. 10.1124/dmd.113.050971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sardari S.; Shokrgozar M. A.; Ghavami G. Cheminformatics Based Selection and Cytotoxic Effects of Herbal Extracts. Toxicol. In Vitro 2009, 23, 1412–1421. 10.1016/j.tiv.2009.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbados Drug Service, 2022. https://www.gov.bb/Departments/drug-service.

- Kim S.; Chen J.; Cheng T.; et al. PubChem in 2021: New Data Content and Improved Web Interfaces. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, 1388–1395. 10.1093/nar/gkaa971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieger E.; Darden T.; Nabuurs S. B.; Finkelstein A.; V G. Making Optimal Use of Empirical Energy Functions: Force-Field Parameterization in Crystal Space. Proteins 2004, 57, 678–683. 10.1002/prot.20251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan Y.; Wu C.; Chowdhury S.; Lee M. C.; Xiong G.; Zhang W.; Yang R.; Cieplak P.; Luo R.; Lee T.; et al. A Point-Charge Force Field for Molecular Mechanics Simulations of Proteins Based on Condensed-Phase Quantum Mechanical Calculations. J. Comput. Chem. 2003, 24, 1999–2012. 10.1002/jcc.10349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wishart D. S.; Knox C.; Guo A. C.; Shrivastava S.; Hassanali M.; Stothard P.; Chang W. J. Drugbank: A Comprehensive Resource for in Silico Drug Discovery and Exploration. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006, 34, 668–672. 10.1093/nar/gkj067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateman A.; Martin M. J.; Orchard S.; et al. UniProt: The Universal Protein Knowledgebase in 2021. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, 480–489. 10.1093/nar/gkaa1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burley S. K.; Bhikadiya Charmi B. C.; et al. RCSB Protein Data Bank: Powerful New Tools for Exploring 3D Structures of Biological Macromolecules for Basic and Applied Research and Education in Fundamental Biology, Biomedicine, Biotechnology, Bioengineering and Energy Sciences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, 437–451. 10.1093/nar/gkaa1038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterhouse A.; Bertoni M.; Bienert S.; Studer G.; Tauriello G.; Gumienny R.; Heer F. T.; de Beer T.A.P.; Rempfer C.; Bordoli L.; Lepore R.; Schwede T. SWISS-MODEL: Homology Modelling of Protein Structures and Complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, 296–303. 10.1093/nar/gky427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Studer G.; Rempfer C.; Waterhouse A. M.; Gumienny R.; Haas J.; Schwede T. QMEANDisCo—Distance Constraints Applied on Model Quality Estimation. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 505–511. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu457. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service. Dr. Duke’s Phytochemical and Ethnobotanical Databases, 2021. https://phytochem.nal.usda.gov/.

- Trott A. J.; Olson AutoDock Vina: Improving the Speed and Accuracy of Docking with a New Scoring Function, Efficient Optimization, and Multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. 2010, 31, 455–461. 10.1002/jcc.21334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y.; Xia X. M.; Lingle C. J. The Functionally Relevant Site for Paxilline Inhibition of BK Channels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2020, 117, 1021–1026. 10.1073/pnas.1912623117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox M. M.; Nelson D. L.. Lehninger Principles of Biochemistry, 7th ed.; W.H. Freeman & Co Ltd, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Overington J. P.; Al-Lazikani B.; Hopkins A. L. How Many Drug Targets Are There?. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2006, 5, 993–996. 10.1038/nrd2199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howitt C.; Hambleton I. R.; Rose A. M. C.; Hennis A.; Samuels T. A.; George K. S.; Unwin N. Social Distribution of Diabetes, Hypertension and Related Risk Factors in Barbados: A Cross-Sectional Study. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e008869 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao X.; MacKinnon R. Molecular Structures of the Human Slo1 K+ Channel in Complex with Beta4. eLife 2019, 8, e51409 10.7554/eLife.51409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellison D. H. Clinical Pharmacology in Diuretic Use. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2019, 14, 1248–1257. 10.2215/CJN.09630818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Drug Development and Drug Interactions. Table of Substrates, Inhibitors and Inducers, 2022. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-interactions-labeling/drug-development-and-drug-interactions-table-substrates-inhibitors-and-inducers.

- Striessnig J.; Koschak A. Exploring the Function and Pharmacotherapeutic Potential of Voltage-Gated Ca2+ Channels with Gene Knockout Models. Channels 2008, 2, 233–251. 10.4161/chan.2.4.5847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killer M.; Wald J.; Pieprzyk J.; Marlovits T. C.; Löw C. Structural Snapshots of Human PepT1 and PepT2 Reveal Mechanistic Insights into Substrate and Drug Transport across Epithelial Membranes. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabk3259 10.1126/sciadv.abk3259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.