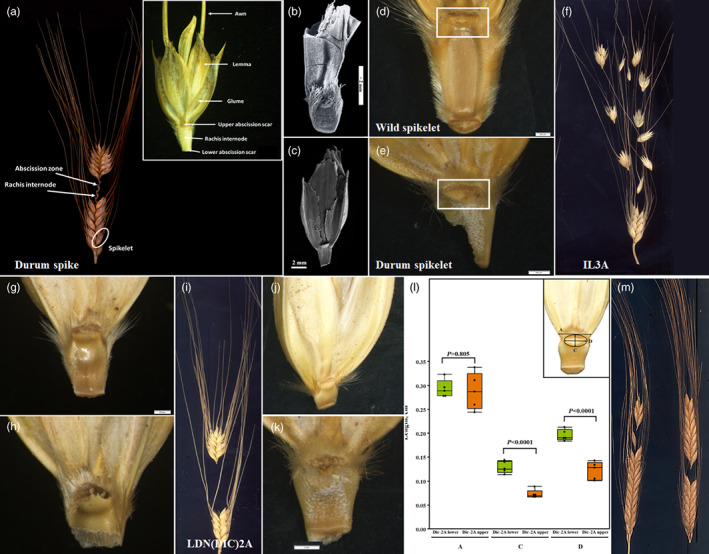

FIGURE 1.

Spike brittleness in wheat. (a) Terminology of the wheat spike organs, depicting the rachis segments and spikelets and a single spikelet in ventral view. Archaeobotanical samples of (b) wild spikelet from the Ohalo II (dated 23,000 years ago) and (c) domesticated spikelet from the A'rugot cave (dated to the second century AD). (d) Wild emmer wheat (Triticum turgidum ssp. dicoccoides) spikelet with smooth wild abscission scar, and (e) durum wheat (T. turgidum ssp. durum) spikelet with a jagged break. (f) The phenotype of introgression line (IL)‐3A with intermediate brittle rachis and an abscission scar (g), an upper (smooth scar similar to wild wheat), and (h) bottom (rough edges torn from the nonshattering rachis similar to domesticated durum wheat). (i) The phenotype of wild emmer chromosome substitution line LDN(DIC)2A with an intermediate brittle rachis and an abscission scar of (j) an upper and (k) bottom parts of the spike. (l) Measures of the A (maximal width of the spikelet base, above the scar), D (scar width), and C (scar length) (based on Snir & Weiss, 2014). p‐Values represent differences between upper and lower spikelets, t‐test (n = 6). (m) A representative photo of mature spikes of domesticated emmer (T. turgidum ssp. dicoccum) cultivars, with quasi‐brittle rachises.