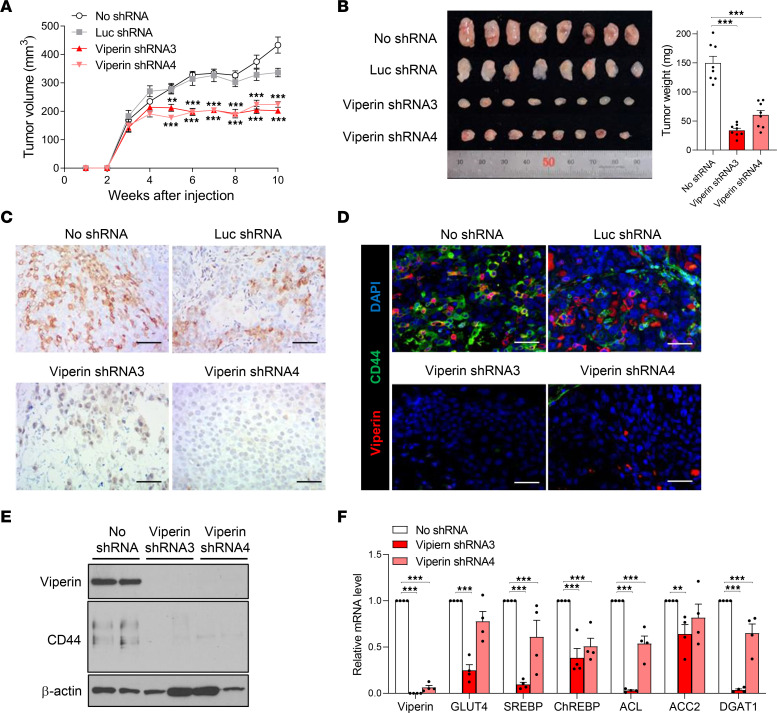

Figure 6. Viperin drives the metabolic phenotype and cancer progression in vivo.

(A and B) Tumor growth in the MKN28 control and viperin-KD cell–derived xenograft mouse models. (A) Spheroids of the stable cell lines were dissociated and counted. A single-cell suspension was mixed with an equal volume of Matrigel. The mixture (1 × 104 cells/mouse) was injected subcutaneously into the flanks of 6-week-old male nude mice (n = 8/cell line). Tumor growth was monitored weekly, and the tumor volume was measured using a metric caliper. (B) After 10 weeks, mice were sacrificed, and tumors were isolated. Tumor size and weight were measured. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM (n = 8). (C and D) IHC staining for viperin (C) and immunofluorescence staining for viperin and CD44 (D) in tumors isolated from the stable cell–derived xenograft mouse models. Tissue sections were stained with specific mAbs against CD44, a CSC marker, and viperin. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Scale bars: 100 μm. (E) Expression of viperin and CD44 in the isolated tumors. Each protein was detected by immunoblotting using specific mAbs. β-Actin was used as a loading control. (F) Lipogenesis in the isolated tumors. Relative mRNA levels of the indicated genes in tumors were measured by qRT-PCR and normalized to ACTB mRNA. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM (n = 4 in triplicate). **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001, by 1-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple-comparison test (A, B, and F).