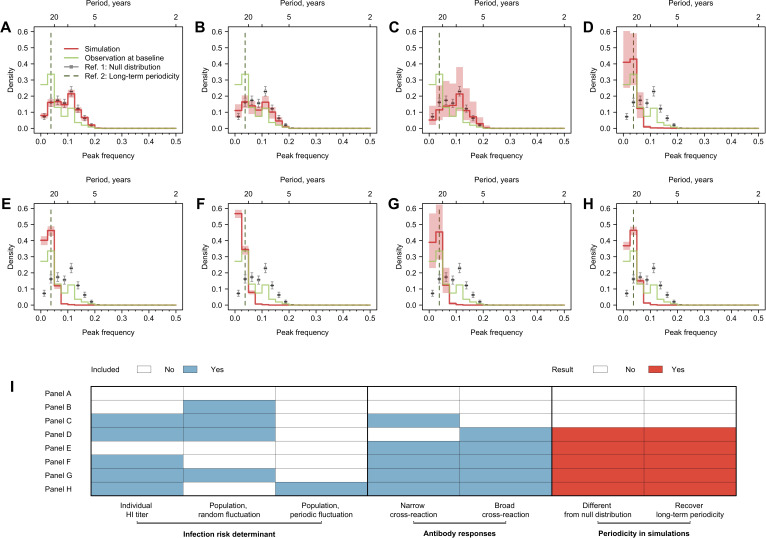

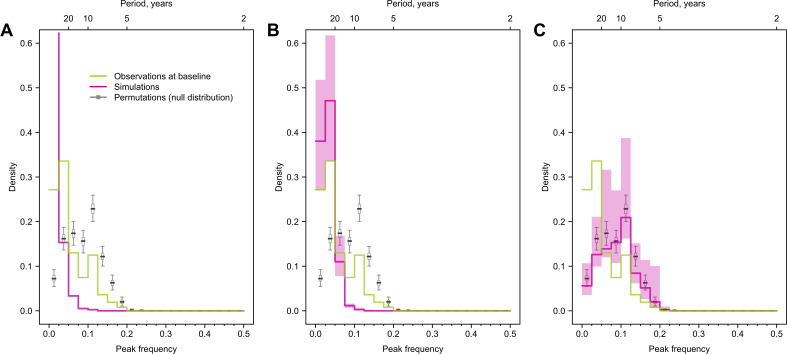

Figure 3. Cycles in simulated antibody responses from the model accounted for different mechanisms.

Colored lines are the distribution of peak frequencies detected in the simulated antibody profiles across individuals. Gray lines are the distributions of peak frequencies of the 1000 permutations of the simulated antibody profiles. For each scenario, we simulated the life course of infections and immune responses for 777 individuals of the same age as the participants in our study and extracted the antibody profile in 2014 for the year’s corresponding to when our 20 strains were isolated. (A) No biological mechanisms were modeled, and the individual risk of infection each year was purely random with a fixed probability of 0.2. (B) Narrow (i.e., against antigenically similar strains) and broad (i.e., against distant strains) cross-reactions of antibodies were modeled, which would however not affect individual risk of infection every year (i.e., the risk of infection each year was purely random with a fixed probability of 0.2). (C) Individual risk of infections was modeled as the randomly varied population-level H3N2 activity every year (i.e., not affected by individual antibody responses), no cross-reactions of antibodies were modeled. (D–F) Narrow and broad cross-reactions of antibodies were modeled, with greater cross-reactions conferring higher level of protection. Population-level H3N2 activity were modeled as constant (D), randomly (E), and periodically (F) varied, respectively. (G) Broad cross-reactions of antibodies were modeled, with greater cross-reactions conferring higher level of protection. Random variations in population-level H3N2 activity were modeled. (H) Narrow cross-reactions of antibodies were modeled, with greater cross-reactions conferring higher level of protection. Random variations in population-level H3N2 activity were modeled. (I) Biological mechanisms included in models that generated results in (A–H).