Abstract

This study examines academic teachers' agency and emergency responses, prompted by the physical closure of universities and university colleges due to the COVID-19 crisis. The pandemic-related lockdown accelerated the digitalization of education and forced teachers to adjust their teaching. A theoretical model is elucidated, in which teachers' agency is understood as the willingness to engage in iterational, practical-evaluative, projective, and transformative action despite the existence of practical, personal, and institutional constraints. We explored the nature and degree of this agency through a survey of university teachers in Norway in the first month of the lockdown. Teachers attempted to create learning environments that facilitated knowledge transfer and interaction and sought to solve problems through self-help and support from colleagues and network, although many struggled with insufficiently developed digital competence and institutional support. Latent profile and qualitative analyses revealed different clusters of teacher responses, from strong resistance to online teaching through to transformation of teaching practices. Qualitative analyses unveiled different expressions of teachers' agency, both ostensible and occlusive, whereby action was shaped by constraining circumstances. These findings can inform future studies of online teaching, indicate the conditions for development of teachers’ digital competence, and illustrate the challenges brought about by crises.

Keywords: Online teaching, Teacher agency, Digital competence, COVID-19, Digital technologies, Higher education

1. Introduction

The physical closure of higher education institutions due to the COVID-19 crisis accelerated the digitalization of teaching in the sector at record speed, but also required academic teachers to adjust immediately their educational activities. In the context of the lockdown that followed the COVID-19 outbreak, teaching - predominantly online - was highly contingent. And, as may typically occur in a crisis, the pandemic triggered the emergence of countervailing forces. On one hand, digitalization allowed academic teachers to expand educational repertoires and challenge the status quo (Aagaard & Lund, 2020). On the other hand, they were confronted with the challenges of online teaching, pressed to mobilize digital competence, and to design and deliver a successful learning experience in a difficult and time-constrained context (Langford & Damsa, 2020). Online teaching became thus the function of the integration of diverse elements (disciplinary, pedagogical, personal, organizational, and technological)–with the expectation that teachers would manage productively the dynamics of this process.

This study examines the nature of teachers' activities and experiences in this crisis context, which spawned numerous challenges but also provided opportunities for transformation of teaching practices. It engages empirically with academic teachers’ reported activities during the first weeks of the COVID-19 lockdown, and ignites reconceptualizations of the notion of agency and its instrumental value in understanding teaching in circumstances where extraordinary efforts are required.

The overwhelming bulk of scholarship on higher education during the first weeks of the COVID-19 pandemic is focused on student experiences. However, the fledgling scholarship on the experience of teachers' perspective suggests that many embraced online learning, although with varying motivations and commitment (Giovannella & Passarelli, 2020; Nambiar, 2020; Tartavulea et al., 2020). It also suggests several contingencies such as the additional time teachers use to design and plan for online teaching and assessment, and identify, access and (learn to) use digital resources for teaching (Langford & Damsa, 2020; Rapanta, Botturi, Goodyear, Guàrdia, & Koole, 2020; Watermeyer et al., 2020). Others highlight the importance of teachers’ digital literacy (Hjelsvold et al., 2020) and institutional support and guidance (Jankowski, 2020).

The research on COVID-19 teaching, in parallel to other (longstanding) studies attempting explanations of factors affecting online teaching (Hofer, Nistor, & Scheibenzuber, 2021), indicates that the pandemic crisis placed pressure on individual teachers’ established teaching practices. It also challenged organizational and technical infrastructure that usually form the core support structures in the teaching process. In this precarious context, the customary practices and professional competencies of teachers may be revealed as irrelevant or insufficient (Jankowski, 2020). Performing teaching in the face of the crisis becomes thus an endeavor that requires a skillful combination of assuming responsibility and acting, together with the management of (institutional and other digital) resources (Eteläpelto et al., 2013; Langford & Damsa, 2020).

In these circumstances, it becomes ever more important to understand how teachers become agents that act (creatively), negotiate, and integrate pedagogical and digital resources into meaningful teaching practice, under severe and limiting constraints. In this study, we argue firstly that grasping the complexity of the transition to emergency online education requires an understanding of teachers’ agency, viewed in relation to the constraints and opportunities of the context, clearly affected by the crisis situation. We understand agency as the capacity of people to act upon their ideas and plans to transform current thinking or practice (Emirbayer & Mische, 1998; Virkkunen, 2016). This can be central for the ways teachers deal with pandemic-determined constraints and engage (potential) opportunities generated by this exceptional situation. Moreover, we take seriously these constraints and argue, secondly, that agency can not be expressed merely as a series of ostensible actions, that is, desirable, ideal ways of acting aimed at achieving a set goal without noteworthy constraints. Rather, notions of agency should incorporate the background constraints under which teachers operate, such as inadequate digital skills or pedagogical knowledge, limiting technical infrastructure or connectivity, or lack of time. This permits us to understand the occlusive dimensions, when constraints prompt a different expression of agency and pursuance of teaching.

Drawing on a survey of academic teachers in Norway in the first month of the COVID-19 lockdown, this article's main aim is to generate a better understanding of what characterizes academic teachers' responses and agency in the context of online emergency education. We address this aim through examining how teachers address challenges and opportunities inherent to the online emergency education context. The Norwegian context is interesting as Norway has been among the leading countries in terms of providing digital infrastructure for educational purposes, while research shows that pedagogical digital competence among teachers at all levels is somewhat lacking (Lund et al., 2014; Skaug et al., 2012). However, with this study, we address a more generic need for knowledge about what constitutes online teaching practices in times of crisis, what can generate challenges or support for successful teaching, and what it takes to proactively engage in performing teaching in adverse conditions. We pursue the aforementioned aim by addressing the following research questions:

-

1)

How can we categorize teachers' responses in the context of the transition to emergency online education?

-

2)

What forms of agency were manifested in teachers' responses in this transition?

-

3)

How can teacher agency be understood and (re)conceptualized in crisis contexts?

Our study intends to make an empirical and conceptual contribution, by revisiting the notion of agency, and by applying this revisited version on teachers’ work in an online emergency context. We operationalize conduct through the way teachers engage with the activity of teaching (i.e., choice/use of teaching methods, digital technologies, and support sought and used to deliver teaching) and the managing of various background constraints (i.e., technical issues, digital and pedagogical knowledge, teaching experience, COVID-19-related challenges). Section 2 reviews literature on online teaching and digital competence and section 3 introduces our key organising concept of agency. Section 4 introduces the methods in our empirical study, section 5 presents the results, and section 6 concludes with a discussion of findings and a potential reconceptualization of agency, and implications for practice.

2. Digital competence and conditions for online teaching

2.1. Teachers’ professional digital competence

In attempting to understand teachers' solutions with online teaching, the dominant focus in the literature has been the process of digitalization and teacher's digital competence (Lund et al., 2019. It is claimed that digitalization impacts human activity, while competence shapes the direction and intensity of digitalization (Aagaard & Lund, 2020; Damsa & Jornet, 2017). Thus, an essential question is what kind of competence(s) are necessary to engage in the type of emergency teaching required by the COVID-19-genereated lockdowns and crisis.

The digital literacy, or competence, of teachers is a regular topic of the discussion in research and practice. It has been explored in various studies under different names, e.g., digital competence, ICT literacy or digital skills (Calvani et al., 2012; Fraillon et al., 2013; Zhong, 2011). Professional digital competence entails the ability to access and employ digital resources for pedagogical purposes (Gudmundsdottir & Hatlevik, 2018). Further, it is not uncommon for studies to find that academics possess diversified attitudes (or postures) towards use of digital technology and teaching online, which has an impact on both the frequency and quality of use, and success of innovations involving technology (Buchanan et al., 2013; Scherer and Howard, 2020).

Models, descriptors, and descriptions have been further developed to capture the required competence for educators in digital learning environments. The review study of Ilomäki et al. (2016) depicts digital competences as consisting of: technical competence, the ability to use digital technologies in a meaningful way for working, studying and in everyday life, the ability to evaluate digital technologies critically, and motivation to participate in digital cultures. The same researchers indicate that teachers' digital competence can easily remain underdeveloped, as technology evolves rapidly and teachers may not be able to keep the pace or underestimate the value of such competence in comparison to other academic competences. Gudmundsdottir and Hatlevik (2018) generated the following taxonomy: (a) generic digital competence entails instrumental skills, knowledge and attitudes teachers need to make use of ICT in their practice, including use of software; (b) subject-matter digital competence refers to the particulars of every subject and how each can be taught with and through ICT; and (c) profession-related digital competence includes translation of knowledge and skills into concrete pedagogical models, activities, materials, that enable the teaching act (e.g., communication, online assessment and feedback in a technology-rich environment, relational skills). Finally, Aagaard and Lund (2020) add that transformative digital competence captures students' and educators’ competence in reforming and renewing their teaching practices, and arises as a necessity when teachers are placed in demanding situations. In this study, we build on especially this latter notion, in the attempt to understand whether and how teachers acted in a situation that required fast mobilization of both digital knowledge and skills, ability to navigate the online landscape for technical or pedagogical solution, assemble and use digital resources, or collaborate, in order to make teaching happen under palpable constraints.

2.2. Context and conditions for the transition to online teaching

Several studies have examined conditions for the successful transition to online teaching, constituted of, primarily, institutional arrangements, e-learning infrastructures, and digital leadership. King and Boyatt (2014) demonstrate that, besides teachers' effort and performance, factors such as institutional and digital infrastructure, support and guidance structures or students' expectations and participation play a role in the way digital teaching is performed. Pettersson (2018) makes clear that there is a need for integrated understanding of individual teachers’ decisions, their organizational context, and the learning technologies they use. Such an approach implies both acknowledgment of the value and input brought in by various parties and fields of practice, as well as the intricate and challenging process of making drastic innovations, such as implementation of e-learning, into a successful endeavor. At the same time, it implies understanding of how teachers view and position themselves in relation to the institutional support structures. Concretely, it is of relevance whether such support structures and resources are provided, whether teachers are aware of and have access to these, and whether these are being employed and experienced as meaningful for teaching (cf. Gudmundsdottir & Hatlevik, 2018).

Moreover, the importance of access to resources, both in institutional context and through professional communities of informal networks should not be undervalued. The dynamics of the knowledge domains and abundance of readily-available virtual resources require teachers to navigate complex, knowledge-laden environments and engage with rich and varied sets of resources. In such contexts, teaching also relies on efforts to “assemble an epistemic space” (Markauskaite & Goodyear, 2017) in which individual or collective goals and needs are addressed by capitalizing on conceptual or practical knowledge, others’ expertise, or other digital material resources. Luckin (2018) states that the richest ecologies of resources are not often those provided institutionally, as institutional norms, structures and complexity limit the fluidity and flexibility, but by online environments and communities, or even social media. This opens up for an entire new world of resources and opportunities, not always accounted for institutionally but which teachers may consider in informal ways (Looi et al., 2019). However, none of the above literature examined the dynamics of how teachers engage with online resources and opportunities in a crisis context.

2.3. Studies of online teaching in pandemic context

The research on how academic teachers in different countries have transitioned to online education during emergencies, especially the COVID-19 pandemic, is limited. Peer-reviewed COVID-19-related studies focus mostly on the experiences and views of students (Demuyakor, 2020, amongst many), and the same applies for a large number of evaluation reports. With some exceptions, the studies that do address teachers either fail to separate students from teachers in reporting survey results (Slimi, 2020), or provide only general reflections and recommendations on the transition (Bao, 2020; Dhawan, 2020; Rapanta et al., 2020; Rashid & Yadav, 2020).

However, several evaluation reports do focus on teachers. Dolonen and colleagues’ (2020) analyse the responses of 826 academic teachers in Norway after the first semester of pandemic teaching and find that a majority had little experience with online education but were quick to adopt new technologies and seek support from colleagues (as well as IT support). Teachers reported using considerably more time with teaching preparation and slightly less interactive learning methods. Similar but varied findings can be found in reports from other countries and institutions. Giovannella and Passarelli (2020) surveyed 546 university educators in Italy and found that although university educators engaged in the digital transition, they were more negative than school teachers to online education and less likely to change their teaching. Fox et al. (2020) surveyed 5300 faculty members in the United States and found that those at faculties with existing online infrastructure had a more favourable view of the impact of online education; and the use of staff of IT and pedagogical support appears comparatively high. Hjelsvold et al. (2020) interviewed 22 computer science educators in Norway, who reported both high levels of prior online experience and positive experiences with the COVID-19 transition, but lamented their lack of pedagogical competence.

Turning to peer-reviewed research, Tartavulea et al. (2020) surveyed 362 professors and students from thirteen European countries and found that, while teachers were quick and positive in adapting the methods, the majority indicated they would return to traditional methods after the first lockdown. At the same time, higher degrees of institutional support and trust in the online system were positively associated with the perceived effectiveness of online education. Watermeyer et al. (2020) presents a more dystopic picture after a survey of 1148 academics in the United Kingdom (UK), where teachers report an abundance of ‘afflictions’, and that online education is engendering significant dysfunctionality and disturbance to their pedagogical roles and their personal lives. Elsewhere, Nambiar (2020) surveyed 70 university teachers in India and found that while many experienced challenges with online crisis teaching, 34.2% agreed with the statement that online classes make them conscious about their teaching skills, highlighting the potential for the transformative impact of digitalization on pedagogy.

3. Agency and emergency online teaching

Teachers' efforts to deliver emergency online teaching should not be seen as an isolated phenomenon neither through the lens of the single teacher, their qualities, attitudes, conceptions or actions, nor only through that of the institutional and cultural context. While teachers’ competences, postures, and actions are an individual responsibility, the way these are deployed is a function of organizational and cultural factors, embedded in educational, or even wider contexts. Also, technology and practice are intertwined and possess transformative potential, as new digital resources and tools not only support the planning and delivery of teaching, but also carry the potential to trigger new/adjusted practices (Damsa & Jornet, 2017).

We pose that, to understand teachers’ conduct in the crisis context, a relational perspective on the process is required (Damsa & Jornet, 2017; Edwards, 2005; Stetsenko, 2016). This entails viewing the elements of the (teaching) environment - the teacher, resources, tools, institutions, infrastructure, communities - in a dynamic relationship. Teachers are seen as central in this web of relationships, as they exert a noteworthy degree of influence on how all these elements together generate situations and conditions that make (online) teaching possible, while dealing with contingencies and constraints. In this context, agency emerges as a central notion, with the potential to generate understanding of how teachers position themselves and engage in this endeavor.

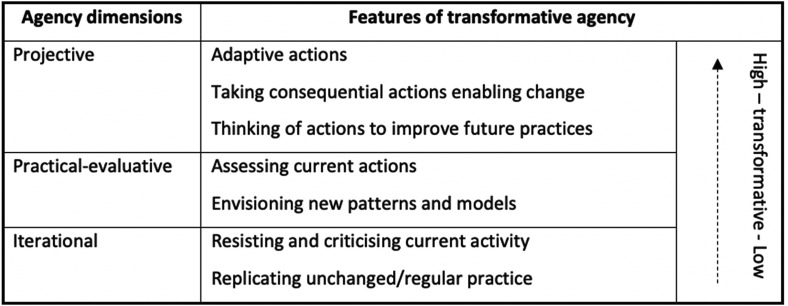

Our conception of agency goes beyond traditional sociological notions (see Biesta & Tedder, 2006), which are often characterized by dueling approaches. In an individualist stance, agency is opposed to structure, with the individual being the only driver of decision-making and action. In an holistic stance, emphasis is given to the prevalence of routinised action as following from the already established order (cf. Bourdieu, 1990; Giddens, 1991). A relational perspective overcomes such dualist stances and offers space for identifying multiple dimensions of agency (Emirbayer & Mische, 1998). First, an iterational dimension is manifested in the ability to recall, select, and capitalize on the existing body of knowledge and practices. In emergency online teaching, this may refer to teachers' ability to make use of ‘regular’ teaching, digital competences, and resources. Second, a practical–evaluative dimension involves momentary judgment of and decision-making in means and ends of action, which can involve maintaining the status-quo or changing/adjusting actions or relationships. In teachers' case, this may refer to assessing the specific constraints and opportunities, as well as the need to change current teaching (online) approaches. Finally, a projective dimension implies orientation toward the future, not merely repeating past routines but reconsidering and reformulating plans, which enables transformation and alternative responses to problems. In the context of emergency online teaching, such reflexivity may include the ability to envision new/tailored pedagogical or digital solutions.

This projective dimension corresponds to the idea of transformative agency. As invoked by Virkkunen (2016), transformative agency is manifested in engaging conflicts and disturbances in activity. While emergency online teaching context is not a typical conflict situation, we view teaching in this context as ‘fractured’ practice that requires transformation through new solutions and contingent action. Haapasaari et al. (2016) identify six dimensions of transformative agency, ranging from resisting and criticizing the current activity, to explicating new possibilities, envisioning new patterns or models, committing to specific actions, and taking the consequential actions needed to change the activity (Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Aligned dimensions and features of agency, baseline framework (Emirbayer & Mische, 1998; Haapasari el al.,2016).

We deem teachers' agency as crucial, because it has the potential to drive and shape teachers' actions in relation to both (newly) available resources, e.g., digital tools and software, but also in dealing with constraints, e.g., underdeveloped digital competences, lack of institutional support, or other challenges. We assume that the iterational, practical-evaluative and projective-transformative are manifest in teachers’ practice during the transition to emergency online teaching. At the same time, we claim that this framework does not capture fully the complexity of agency in a crisis, when the contingency of actions and the need to manage acute constraints, under time pressure and limited support, are much more salient. Moreover, in the emergency context, teachers might not always have a clear idea as to how online teaching may materialize in practice, as the process of identifying digital resources, and making these meaningful for and enacting teaching, is an unfolding field of action.

We, therefore, propose a combined analytical framework, wherein we incorporate teachers' actions, competence, and postures, the opportunities and resources available in the context, together with the background constraints under which teachers operate. In so doing, identify two manifestations of agency. Agency involves a series of ostensible actions, which are expressions of the desired conduct, free of individual or contextual constraints. Yet, when influenced and inflected by contingent factors and constrains, it is important to highlight the occlusive dimensions of agency – controlling our observations of action for the background constraints. This framework has potential to capture whether and how teachers take initiatives in situations that require fast mobilization of (digital) competences and external resources, and thus identify the degree and nature of agency in times of crisis. Moreover, this framework is relevant beyond crisis situations, and can be applied when seeking to identify transformative aspects of teachers’ conduct in the context of the challenges posed by a forced transitioning to online learning, and by (possibly) inconsistent institutional support. It also potentially discloses the relational nature of the entire teaching endeavor, where set/habituated knowledge, competencies, regular teaching resources are no longer sufficient to address such complex, commanding and incalculable challenges.

4. Methods

4.1. Empirical context and participants

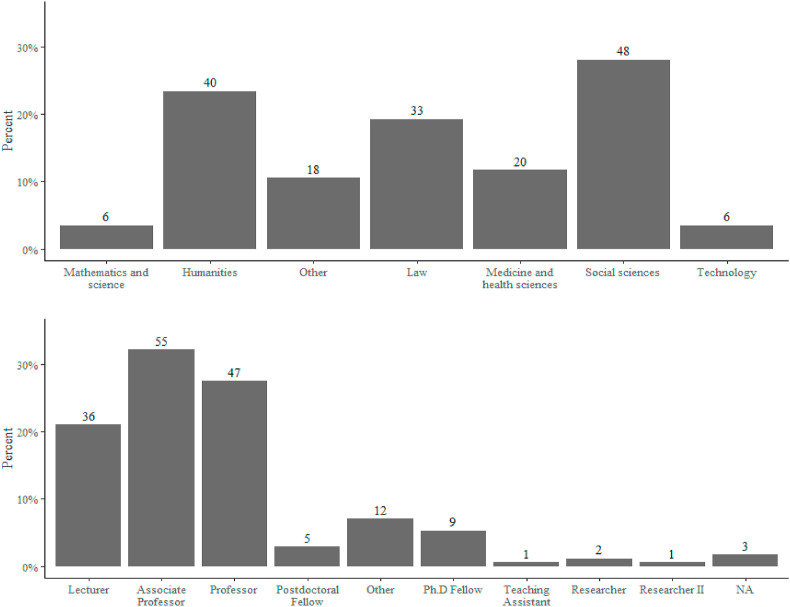

The current study was conducted during the first COVID-19 lockdown in the context of Norwegian higher education. After a national lockdown was introduced on March 12, 2020, academics, administrators and IT-support worked at breakneck speed to put in place full online learning. This was supported by a series of bottom-up initiatives including a Facebook group Digital Teaching in Higher Education, which registered at the time of writing almost 4500 members (Langford & Stang, 2020). The respondents in this study were academic teachers, recruited through an open call published in the named Facebook group. One hundred and seventy-one (171) academics responded to the survey. Disciplines varied, although the sample was dominated by the “softer” fields of humanities, social sciences, and law (Fig. 2 ). The respondents were predominantly in positions with a ‘full’ teaching load: 50% or greater of the position. 28% (48 individuals) of all the respondents were from the Social Science field, 23% were from the Humanities and 19% were from Law Faculties; other faculties combined make up 31% of the respondents.

Fig. 2.

Distribution of respondents by discipline and position (%).

4.2. Data and variables

The survey focused on teachers' experiences during the first month of teaching during the COVID19-lockdown, with a focus on: (1) pre-lockdown competence in online teaching; (2) the use of different digital tools and teaching methods; (3) challenges with online teaching; and (4) potential effects on student learning outcomes. The form contained ten multiple-choice questions with the possibility of free text answers, aimed at collecting participants’ further elaboration on their experiences and tool use as well as suggestions.

Data preparation. The items were categorical variables, and were classified as either ordinal, dichotomous, or nominal. Count data was also calculated using the number of responses a participant selected for items that had multiple responses they could select from (e.g. Question 3: Software used).

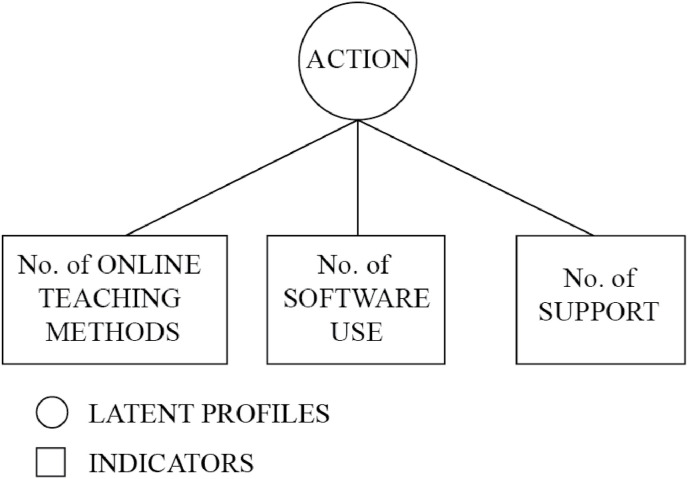

Variables. The quantitative and qualitative analyses for this article were performed on the specific variables that reflected activities, constraints, and overall posture and attitude. The variables for activity are online teaching methods, software use, and support for online learning. As the items were dichotomously scored for these three Activity variables, we used the Kuder-Richardson KR-20 formula to indicate internal consistency (Kuder & Richardson, 1937). Values above 0.70 are considered acceptable for scales comprised of homogeneous items (Thompson, 2010, p. 668); however, no consensus exists on sets of heterogeneous items, such as symptoms or behaviors, without a common cause. The content of the three variables, which are central to the subsequent latent profile analysis, is as follows:

-

(a)

Online Teaching Methods depicts internet-based technologies respondents indicate they have never used in teaching before the lockdown (e.g., group discussions in Zoom break-out rooms) - 12 binary items coded as 0 = No, 1 = Yes; KR-20 reliability = 0.38;

-

(b)

Software use depicts the different types of software teachers used during and for emergency online teaching - 10 binary items; 0 = No, 1 = Yes; KR-20 reliability = 0.36;

-

(c)

Support for online learning depicts the types of support for online teaching that was sought by teachers, and the extent they reached out for support and resources - 12 binary items; 0 = No, 1 = Yes; KR-20 reliability = 0.60.

The Constraints were considered as playing a role in limiting the way teachers engaged in these activities and are: Previous online teaching experience (coded as 1 = No, 2 = Yes, once, 3 = Yes, many times), Level of Difficulty (five point Likert scale coded as 1 = Very Difficult, 2 = Difficult, 3 = Neither difficult nor easy, 4 = Easy, 5 = Very Easy), and Challenges of Online Teaching (multiple-select question with 13 options, such as “Insufficient technical equipment”). Finally, Posture, which is explored qualitatively, depicts the way teachers expressed their experiences and views of their actions during the emergency online teaching.

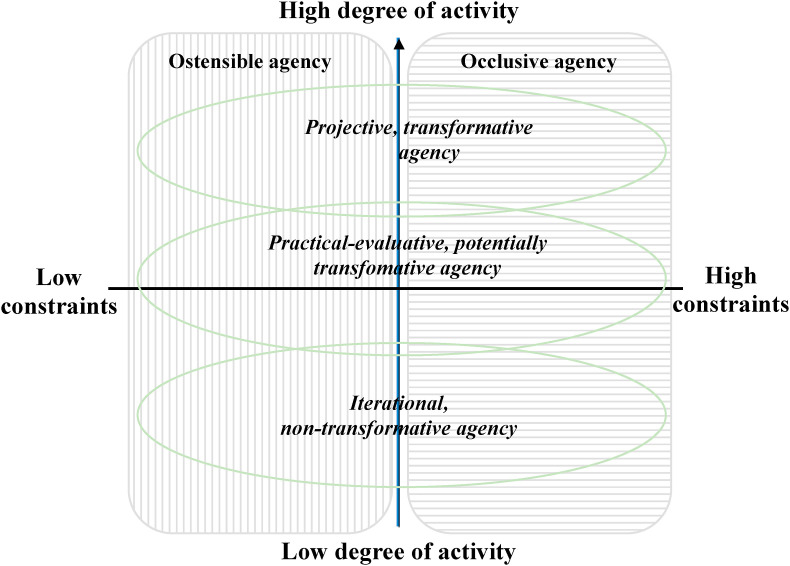

4.3. Analytic framework and data analysis

The multidimensional analytical framework we propose has potential to capture the nuances in agency manifestations in any context (including action during crises), and is novel in that it includes the level of constraint that may mediate (enhance or hinder) activity. The framework has particular consequences for empirical inquiry, as it forces researchers to examine not only ostensible manifestations of agency but also the occlusive manifestations, and provides us with a set of dimensions that can be operationalized into empirical indicators. Specifically, we expect agentic conduct (whether ostensible or occlusive) can be mapped to a multidimensional (2 × 2) structure, featured by activity level and degree of constraint, as opposed to a dichotomist view wherein agency is simply qualified as high or low, repetitive or transformative.

Empirically, the dimension high-low level of initiative/activity is expressed through the three Activity variables and the dimension low-high degree of constraint is expressed through the three Constraint variables. The expectation is that agency leading to addressing the challenges of emergency online teaching would be characterized by intensive use of new methods and new software, combined with active seeking of support and resources (whether institutional or otherwise). At the same time, we conceive of low-high constraints as mediating agency manifestations through the level of activity. We expect that teachers reporting high levels of difficulties and challenges can still express agency of various kind.

Using this proposed framework, we explore manifestations of teachers’ agency in online emergency teaching context through quantitative and qualitative analyses, described below. We use an abductive approach, which, according to Tavory and Timmermans (2014) is “a creative inferential process” (p. 5), “one part empirical observations of a social world, the other part a set of theoretical propositions” (p. 2): a conversation between these two. Such an approach involves a back and forth process between the research evidence and considerations of theory, with a deductive approach in the analysis of quantitative data and an inductive strategy when examining and interpreting the qualitative material.

4.3.1. Quantitative analysis

As this study had a relatively small sample size and categorical response data, we employed categorical data analytical methods (Agresti, 2018). We calculated descriptive statistics (i.e. mean, mode) for each variable (see Supplementary Material, PART A), and employed latent profile analysis (LPA). As part of LPA, three contingency tables were analysed using Pearson Chi-square test. For the descriptive statistics, we used the R package “psych” (R Core Team, 2020; Revelle, 2020) and for LPA we used Mplus version 8.5 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998) (the code for the analysis in Supplementary Material, PART B and C).

Latent Profile Analysis. We conducted LPA on each of the three variables to identify initially unobserved and homogeneous subgroups within the sample (Marsh et al., 2009). LPA is used to identify so-called latent profiles (i.e. action) based on a set of continuous variables (see Fig. 4 ), provides relative fit parameters to ascertain the most appropriate model, and can be extended by variables predicting class membership (Masyn, 2013, pp. 551–611). As we do not intend to draw causal inferences from our LPA models, we use LPA exclusively as an explorative tool.

Fig. 4.

Latent profile model.

The first step in LPA is to select the class indicators, that is, the categorical items used to define the latent classes. Several of the items had very small variance (i.e., too few participants selecting either yes or no) and were thus not included. Identifying the number of profiles represents the second step. Profile enumeration was achieved by performing multiple LPAs with varying numbers of profiles and by comparing the relative fit indices of the resultant models (Masyn, 2013, pp. 551–611). Models with the smallest information criteria values were chosen (Akaike's Information Criterion AIC, Bayesian Information Criterion BIC, and the sample size-adjusted BIC), due to better fit. Also, several likelihood-ratio tests were performed to compare LPA models with k and k-1 profiles, such as the Vuong-Lo-Mendell-Rubin (VLMR), the Lo-Mendell-Rubin (LMR), and the parametric Bootstrapping (B) likelihood-ratio tests (LRTs). In case these tests reveal an insignificant test statistic, the LPA model with k-1 classes was preferred over the LPA model with k classes. These tests, however, are not equally accurate in the identification of the number of profiles, with the BLRT outperforming the VLMR- and LMR-LRT in many situations (e.g., Chen et al., 2017). The optimal LPA model also exhibited high entropy (i.e., classification accuracy), high class membership probabilities, and sufficiently large classes (Marsh et al., 2009). As these evaluation criteria have limitations, the choice of profiles was supplemented by the interpretability and distinction of the latent profiles (Morin & Marsh, 2015). Given the relatively small sample in our study, we reduced the complexity of the LPA models by constraining the variances of the profile indicators to equality (Morin & Marsh, 2015). All models were estimated utilizing robust maximum likelihood estimation and the full information maximum likelihood (FIML) procedure to handle missing data.

4.3.2. Qualitative analysis

The free text answers were analysed through qualitative, thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006). We first developed familiarity with the data, through repeated readings of the transcripts and topic indexing, to identify themes related to our framework that might require further scrutiny. We then systematically labelled the free text data following thematic analysis principles, by tagging the data with indicators depicting activities and constraints. Through this tagging, we could assign the type of conduct identified to one of the four quadrants in Fig. 3. To understand how such indicators may be reflective of agency manifestation, we qualified the combinations of activity & constraints and agency manifestations based on the dimensions and features by Emibayer and Mische (1998) and Haapasaari et al. (2016). Finally, we revisited the qualified material, and clustered it in two overarching categories of agency (ostensible and occlusive agency). While working in this fashion, the possibility of data informing interpretations remained open, with some of the open answers generating further elaborations of the interpretative categories.

Fig. 3.

Multidimensional map of empirical manifestations of agency.

5. Findings

Teachers at all education levels have been thrown into a new teaching situation that required them to undergo many quick changes in their teaching practice. Unsurprisingly, the abrupt transition to online teaching meant many were faced with the need to change their teaching methods. Our findings display a range of activities characterizing this transition and often positive postures towards online teaching and technology, but with great variation. The descriptive account below provides a brief overview of self-reported activities and constraints, followed by the reports on three profiles of conduct identified through LPA, and outcomes of the qualitative analysis, through illustrations and interpretation of teachers’ agency.

5.1. Descriptive account of self-reported transitions to online teaching

5.1.1. Online teaching methods

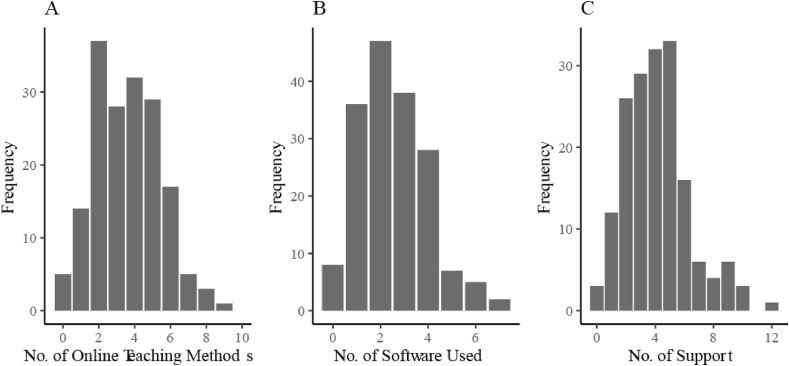

Teachers engaged differently with (new) types of online teaching methods. A majority of respondents live streamed their lectures (59%, SD = 0.49) and 54% (SD = 0.5) supervised students and PhD fellows online (Supplementary Material, Table A1). For the remainder of the other Online Teaching Methods, most participants used them to a lesser extent: 13% (SD = 0.34) recorded lectures and seminars from earlier semesters and 7% (SD = 0.26) recorded a podcast of a lecture or seminar in advance. Live digital teaching was common: 40% lectured live, 60% held live discussions, and 39% held live break-out groups. Students were also provided space to learn in online groups (16%) and new online-based exercises (16%). Most participants on average used 3 to 4 Online Teaching Methods (M = 3.6, SD = 1.83, Mdn = 4; Table A1). The distribution of the number of Online Teaching Methods (Fig. 5 A; Table A6) is approximately symmetric (Skewness = 0.28) and mesokurtic (Excess Kurtosis = −0.37; SE = 0.14). This suggests most participants used less than a third of the teaching methods examined in the survey. However, many teachers appeared to have switched their regular teaching to an online context, without many changes, with many noting that the time was too short to organize new ways of teaching. Free-text answers show teachers positioning towards trying new teaching methods (or trying new formats in online environments) but not always succeeding or enjoying the situation, as it often placed them in vulnerable positions. These findings indicate a possibility of expression of various type of agency (from evaluative to transformative).

Table 1.

Fit indices, entropies, and likelihood-ratio tests for the LPA models.

| Model | N | k | npar | LL | LLCF | AIC | BIC | aBIC | Entropy | VLMR p-value | LMR p-value | BLRT p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Profile | 171 | 1 | 6 | −1032 | 1.1 | 2076 | 2095 | 2076 | 1.00 | |||

| 2 Profiles | 171 | 2 | 10 | −1010 | 1.3 | 2040 | 2071 | 2040 | 0.68 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.00 |

| 3 Profiles | 171 | 3 | 14 | −1000 | 1.8 | 2028 | 2072 | 2027 | 0.65 | 0.59 | 0.59 | 0.00 |

| 4 Profiles | 171 | 4 | 18 | −993 | 0.9 | 2023 | 2079 | 2022 | 0.79 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.05 |

| 5 Profiles | 171 | 5 | 22 | −989 | 1.2 | 2022 | 2091 | 2021 | 0.72 | 0.75 | 0.76 | 1.00 |

Notes. N = Sample size; k = Number of latent profiles; npar = Number of parameters; LL = log-likelihood value; LLCF = log-likelihood correction factor; AIC = Akaike's Information Criterion; BIC = Bayesian Information Criterion; aBIC = sample size-adjusted Bayesian Information Criterion; VLMR = Vuong-Lo-Mendell-Rubin Likelihood-Ratio Test; LMR = Lo-Mendell-Rubin Likelihood-Ratio Test; BLRT = Parametric Bootstrapped Likelihood-Ratio Test.

Fig. 5.

Histogram plots of (A) number of online teaching methods, (B) number of software used and (C) number of support.

Table 6.

Excerpt 3. Projective, transformative agency manifestations.

| Teacher statement | Indicators of Activity and Constraint management |

|---|---|

| Adaptive and generative use of methods, technologies and accumulated knowledge | |

|

a. ‘Zoom to larger meetings, Teams to smaller. Discussions worked really well for both students and me. Want to use this more for teaching and cross-border meetings. […] Amazing that we have so many good experiences with this now, to keep and use in the future … ’ b. ‘"Classroom" in (software name) seems more intimate and enjoyable than in Canvas. Students seem to digitally "thrive" there! Easy to collaborate with that topic team too, in parallel teamrooms. Very valuable and effective. Will probably retain this form of cooperation when we return to face-to-face teaching again.’ c. ‘Learning how the platforms work by trial and error, day by day. Trying to figure out how something looks from the students’ side […]. Good lessons for the future! |

Teaching activities and use of various software. Adaptive use of digital tools for collaborative online work. Indication that constraints existed (size of group, physical distance) but have been overcome (a) Adaptation and evaluation of specific software features for own teaching and for students learning. Constraints are being turned into potential (b) Regular try-out of digital software, but thoughtful evaluation mindful of students' situation and constraints. (c) Orientation towards future use of software and gathered experiences. (a-c) |

| Expanded practice in gathering resources | |

|

d. ‘Building on the experience of designing MOOCs and online courses’ e. Various instructional videos on Youtube have been very useful in terms to understand Zoom.’ f. ‘Have participated in digital conferences that have given me greater insight into digital platforms - zoom, basecamp - and how these can be used flexibly (breakout groups, chat) and integrated with different tools (mentimeter, Jamboard). But has also gained greater respect for the importance of digital-educational competence and for how to approach that next … ’ |

Active use of previous knowledge and experience with online teaching (d) Pro-active support seeking beyond institutional resources (e, f) Flexible orientation and action to make adaptive use of digital software (f) Proactive engagement and work with overcoming constraints (e.g. lack of digital competence) (f) Expansive practice in seeking and using resources (d-f) |

| Expanded engagement with online teaching | |

|

‘Responsibility that I have been assigned (as a resource person for digital education) has helped me to get into new things faster, gain an overview and be motivated to help others.’ ‘It is a very special situation, and one goes a little further than usual to facilitate student learning. […] transition to fully digital education has been an additional motivating factor for implementing changes in the form of teaching that exploit the opportunities that exist in digital tools.’ |

Reporting of gains and overcoming constraints when assuming responsibility for supporting others (g) Proactive posture and report of additional effort to address the transitions challenge. Difficulties/constraints turned into motivational value (h) Projective posture by envisioning value of engagement and additional efforts (g-h) |

5.1.2. Software used

The two most commonly used software packages were Zoom (80%; SD = 0.4) and Canvas (61%, SD = 0.49), while Adobe Connect (5%; SD = 0.21) and Google Drive (9%; SD = 0.28) were used the least. Less than 30% of the participants used the other remaining software (Supplementary Material, Table A2). The largest number of software programmes used by two participants was 8, while eight participants used only one software listed in the survey (Fig. 5B). The median number of software used was 2 and on average participants used between 2 and 3 software's (M = 2.54; SD = 1.46; Table A6). The count data for Software Used was moderately positively symmetric (Skewness = 0.58) and mesokurtic (Excess Kurtosis = 0.16; SE = 0.03; supplementary material, table A6). All this suggests that most participants use less software than commonly provided at universities. Overall, teachers expressed varying views of using new technologies for teaching, with a prevalence of indicating that digital competence was less of a problem for some respondents as were technical infrastructure issues and combined (non-teaching) challenges. While here too various type of agency are possibly expressed, occlusive agency is most likely.

Table 2.

Average latent profile probabilities.

| Profiles | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Average Latent Profile Probabilities | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 1 | 0.79 | 0.21 | 0.00 |

| 2 | 0.14 | 0.85 | 0.01 |

| 3 | 0.00 | 0.11 | 0.89 |

5.1.3. Support

Most participants overwhelmingly sought and found support in resources on the internet (71%; SD = 0.45). About 82% (SD = 0.39) of participants tried things out themselves. While slightly more than a half of participants (53%; SD = 0.5) used Facebook groups for support. The least selected support categories were help desk at own institution (12%; SD = 0.33), resources from pedagogical centers (13%; SD = 0.34) and asking colleagues with pedagogical competence (13%; 0.34; see Supplementary Material, Table A3). Fig. 5C shows that only one participant used 12 digital support resources and two participants used none of the support resources, while participants used on average four support resources (M = 4.12; SD = 2.20; Mdn = 4). The count data were moderately positively skewed (Skewness = 0.75; Supplementary Material, Table A6). All this information suggested that participants were less inclined to use support/institutionally-provided resources mentioned in the survey, and most participants used only a third of the support resources. Free text answers indicate that teachers' own motivation to learn how to teach online, coupled with a sense of responsibility for delivering good teaching to help students to learn in this difficult period, drove teachers’ efforts to seek support beyond institutional boundaries. Both ostensible and occlusive agency are likely.

Table 3.

Proportion table between three profiles and five challenges.

| Profiles | Equipment |

Competence |

Network |

Routine |

Uncertainty |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Low | 0.30 | 0.07 | 0.23 | 0.13 | 0.32 | 0.05 | 0.32 | 0.05 | 0.25 | 0.12 |

| Moderate | 0.45 | 0.10 | 0.34 | 0.21 | 0.39 | 0.16 | 0.46 | 0.09 | 0.30 | 0.25 |

| High | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.04 |

| Sum | 0.80 | 0.20 | 0.63 | 0.37 | 0.76 | 0.24 | 0.82 | 0.18 | 0.60 | 0.40 |

| p-value | 0.13 | 0.96 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.21 | |||||

Note. p-value = Fisher Exact test p-value; Equipment = Insufficient technical equipment; Competence = Insufficient technical competence; Network = Poor network connection; Routine = Difficulties of structuring a digital working day/routine; Uncertainty = Uncertainty about what is the best pedagogical approach.

5.1.4. Other variables - constraints

The survey also measured several other variables including: 1) Previous online teaching experience; 2) Difficulty experience; 3) Challenges with online teaching (Supplementary Material, Table A5), conceptualized as Constraints. When it comes to Previous online teaching experience, 121 participants or 71% reported they had no experience (M = 2.62; SD = 0.66; Mdn = 3; coded as 1 = Yes, many times, 2 = Yes, once, 3 = No). Only 18% selected “Yes, many times”, while 10% reported that they have used online teaching once. The data are negatively skewed (Skewness = −1.48), and most participants were inclined to answer “No” in the survey. The median of Difficulty experience was 3 (range was 1 to 5), and, on average, participants found online teaching neither difficult nor easy (M = 3.25; SD = 1.05). The average number of challenges with online teaching was 3 (M = 3.04; SD = 1.86; Mdn = 3). The Challenges data were moderately positively skewed (Skewness = 0.8), indicating that most people had faced fewer challenges. In the free-text answers, teachers indicated technical and pedagogical challenges, most of them related to institutional infrastructure as being the main constraints when setting up online teaching. Lack of digital competence is expressed in insecurity in using new technology on short notice, but insecurity about pedagogical knowledge and time-consuming re-design work are also mentioned. Concurrently, pandemic lockdown-related obstacles, such as inappropriate space at home, childcare issues and illness, were reported as additional constraints. Generally, given the varied and high number of constrains, occlusive agency seems most likely to be expressed in the surveyed participants if they are also relatively active.

Table 5.

Excerpt 2. Practical-evaluative and tentatively transformative agency manifestations.

| Teacher statement | Indications of Activity and Constraint |

|---|---|

| Identifying and evaluating problems with current activities | |

|

a. ‘When I test out new schemes/methods, I am unfortunately inclined to believe that exactly this form of teaching is not ideal digital.’ b. ‘Planning teaching sessions takes a lot time when already made plans need to be rethought, and adapting to a new way of approaching students is time-consuming.’ c. ‘It worked surprisingly well to work in real-time philosophical-dialogic on-line with thorough preparation from the students. Nevertheless, digital dialogic pedagogy cannot replace the same type of pedagogy in physical space’ |

Activity is initiated. Use/try-out of new methods (a) Design and planning of teaching is initiated (b) Online interaction/dialog are used (c) Constraints are implied, through the negative conclusions on tested methods and tools; no indications of constraints being managed. |

| Identifying and evaluating value of new activities (methods, tools) | |

|

d. Delivering increased written communication: more often announcementsto the students, and increased feedbackon previously planned small, mid-term e. We become a little less dynamic and dialogic online. But, when wefound just the right platform, it became a fantastic plan B - which in particular has meant a lot to relatively isolated, financially insecure and concerned international students |

Activity is initiated. Methods tested and adapted to sustain maintain online learning (d) Discussion is used as a method online, use of software. Positive conclusion on effects of initiative taking (e) Active conduct, addressing constraints, by trying out new (combination of) method and digital platforms. |

5.2. Latent profile analysis

5.2.1. Identifying the number of profiles

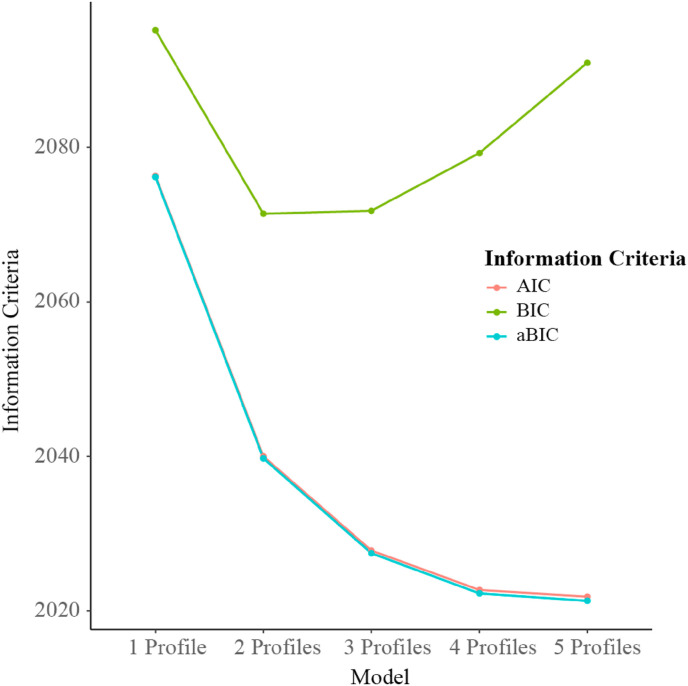

Table 1 shows the relative fit indices, entropies, and the results of the model comparisons for the LPA models with up to five profiles. The information criteria AIC and aBIC decreased with increasing number of profiles, while the BIC decreased for a model with two profiles (Profile 2), but steadily increased with more profiles. The elbow plot of the information criteria indicated two substantial drops between the LPA models with one and two profiles and the LPA models with two and three profiles (see Fig. 6 ). Except for the BIC, these observations suggest that three profiles may exist. The BIC did not differentiate well between the LPA model with two or three profiles. Concerning the model comparisons, the likelihood-ratio tests drew a mixed picture: While the VLMR and LMR tests pointed to the preference of the LPA model with four profiles over the three-profile model (ps < .05), they could not identify a clear model preference for the models with fewer profiles. However, the Bootstrapping test clearly suggested that three profiles could be extracted (p < .05 for all model comparisons up to three profiles and p ≥ .05 for all subsequent comparisons). Besides, the model with four profiles contained one profile with less than 0.6% of the total sample size. Finally, the average latent profile probabilities were sufficiently high for the three-profile solution (Nylund et al., 2007, Table 2 ), and the entropy was substantial (entropy = 0.65). The former provides greater certainty that individuals were assigned to the most likely profiles.

Fig. 6.

Elbow plot of information criteria.

Given these findings, we accepted the LPA model with three profiles, for three reasons. First, it matched our theoretical expectations, patterns in the qualitative data, and need for interpretability (see section 3). The three-profile model permits more meaningful interpretation compared to profiles of high and low activity level. Second, while the VLMR and LMR likelihood-ratio tests were insignificant, previous research suggested that the BLRT and BIC are better indicators of the number of profiles (Nylund et al., 2007), and the aforementioned LRTs may over-extract profiles (Chen et al., 2017). Third, the three profiles were distinguishable and sufficiently large (see Nylund-Gibson & Choi, 2018).

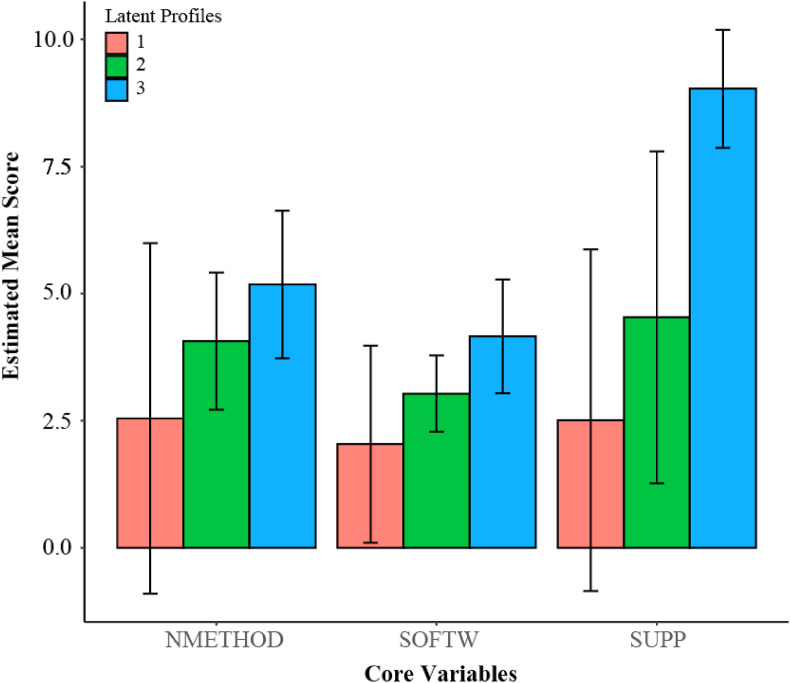

5.2.2. Profiles description

Fig. 7 shows the average counts of the three core variables for the three profiles. The profiles can be described as low, moderate, and high action. Profile 1 covered 36.7% of the participants, profile 2 had 55.2% of the participants, and profile 3 had 8.0% of the participants. Participants classified into profile 1, on average, used few new online teaching methods (M = 2.55, SE = 1.76) and software (M = 2.04, SE = 0.99) and reported only few support offers as helpful (M = 2.51, SE = 1.71). The average numbers of new online teaching methods and the support used were both statistically not different from zero. All this suggests participants in this group could be considered as not acting or only using a small number of software during the university closure. Participants in profile 2 used, on average, a moderate number of new online teaching methods (M = 4.07, SE = 0.69), software (M = 3.04, SE = 0.38) and support (M = 4.53, SE = 1.66). The average number of new online teaching methods (M = 5.18, SE = 0.74), software used (M = 4.16, SE = 0.57) and support found to be useful (M = 9.03, SE = 0.59) was higher in profile 3 than in profiles 1 and 2.

Fig. 7.

Mean scores by profile and core variables.

5.2.3. Describing the profiles with constraints

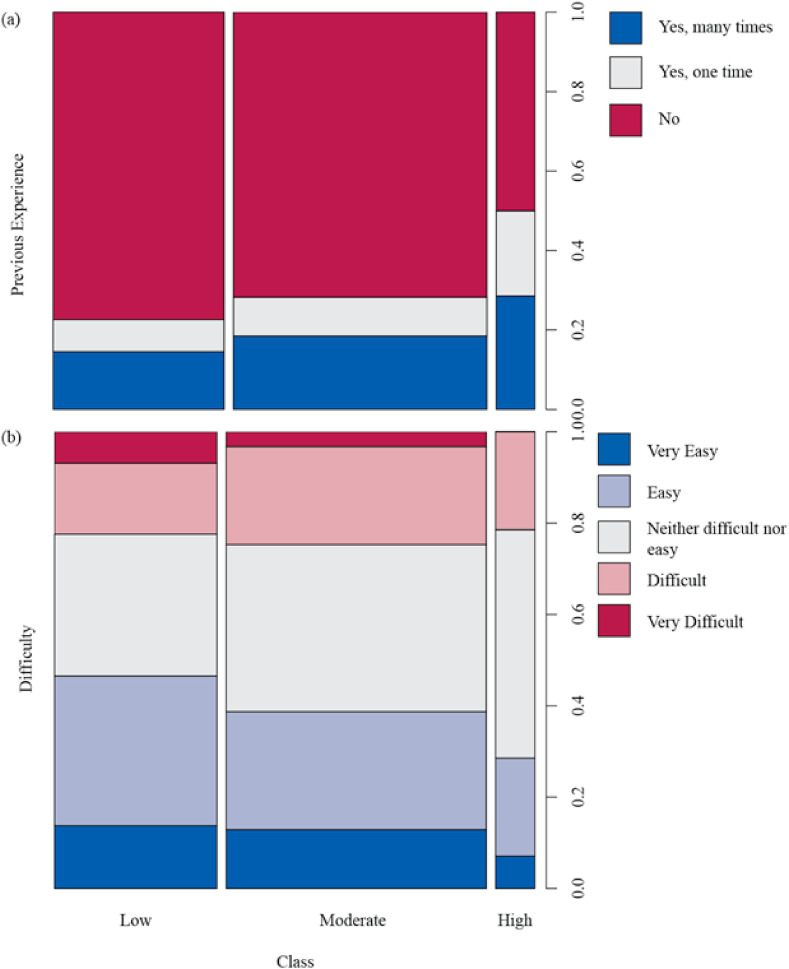

In order to more deeply understand the extent to which agency is expressed in its occlusive dimension (i.e., under constraints), we analyse these three profiles under constrained conditions. This is done by examining the associations between profile membership and the three measured constraints: each participant's previous online teaching experience, difficulty experienced with online teaching and challenges (Fig. 8 b, Table 3 ). Fig. 8 was used to illustrate data for two categorical variables (Fig. 8a: Previous online education experience vs. probable profiles; Fig. 8 b: Challenges experienced vs. probable profiles). The width horizontally represents the proportion of participants in each profile and the colours represent the level of previous experience or difficulty. Using Fisher's exact test on both previous online teaching experience (p = 0.27) and difficulty (p = 0.85) with probable profile classification there were no statistically significant associations. However, there were two statistically significant associations between probable profile classification and two challenges: “poor network connection” and “difficulties of structuring digital working day”.

Fig. 8.

Spineplot for classified profiles and constraints.

Parsing each profile, we can observe the following. Most participants in profile 1 had no previous digital education experience (78%). Many participants found digital teaching easy (34%), while 6% found it very difficult. As can be seen from Table 3 on challenges, 35% said they had insufficient technical equipment (Equipment), 35% had insufficient technical competence (Competence), 21% had poor network connection (Network), 28% had difficulties of structuring a digital working routine (Routine), and 30% were uncertain about what the best pedagogical approach (Uncertain). In their case, agency expressed can (to a large extent) only be occlusive, and only for those who experienced a high degree of constraint. For this sub-group, agency could be transformative, if the few changes undertaken helped realizing/advancing teaching.

In profile 2, a lower proportion indicated “no” previous online teaching experience (72%) while a large number of participants found online teaching neither difficult nor easy (37%). Profile 2 had a higher proportion of participants that said “yes” to the five challenges mentioned than both profile 1 and 3. In comparison to profile 3, more participants had previous online teaching experience (25%), and only 50% had no previous experience. This indicates the degree of constraint related to familiarity with online teaching is more nuanced, and both ostensible and occlusive agency are possibly expressed in this profile.

Participants in profile 3 also had no participants that found it very difficult, and the vast majority (44%) found online teaching neither difficult nor easy. Compared to profiles 1 and 2, profile 3 had a lower proportion of participants who had challenges. This indicates the possibility for expression of mostly ostensible agency. However, as fewer participants in profile 3 than those in profile 2 had experience with online teaching suggests also the probability that some occlusive, and not only ostensible agency, is present.

5.3. Qualitative accounts of agency in teachers’ emergency online teaching

Teachers' ways of transitioning to online teaching involved complex and varied conduct. The LPA-generated profiles represent the baseline for interpreting teachers conduct and manifestations of agency through the multidimensional analytical framework we propose. The qualitative analysis aids these interpretations and provides illustrations of agentic manifestations while handling the online teaching effort in the crisis. The composite overview in the excerpts presents a series of statements, each illustrating teachers' reflection on their own conduct (activity and managing constrains) and manifestation of teachers’ agency, interpreted and qualified in relation to dimensions and features of agency.

5.3.1. Iterational, non-tranformative agency manifestations

The statements in Excerpt 1 (Table 4 ) refer primarily to teaching methods, approaches or strategies and use of new digital software in the context of the fast transition to emergency online teaching.

Table 4.

Excerpt 1. Illustrations of iterational, non-tranformative agency manifestations.

| Teacher statements | Indications of Activity and Constraint management |

|---|---|

| Resisting, Criticizing, Avoiding | |

|

a. ‘Some forms of education […] cannot be replaced with digital teaching in a satisfactory way.‘/Digital teaching and discussion of discipline-related problem can hardly become as good as physical f2f meetings between people’ b. In our field [name of field]; dialog and discussion are important. This is difficult digital. c. Students […] have not developed self-discipline to work more independently. d. ‘I have let the students do all this (au. online activity and communication), both now and in the past.’ |

Activity is reduced to minimum. Reliance on students to (self)organize (d). Negative posture about online teaching and its potential (a). Acknowledgment of difficulty in a ne without providing alternatives (b). Leaving responsibility to students to manage (d), placing responsibility on students for teaching that may not be working (c). |

| Teaching ‘as usual’ | |

|

e. ‘We have a few lectures and student activity, problem solving and group work as usual’. f. ‘Attempted to do the same as otherwise, only digitally.’ g. ‘Used [software name] to post lectures … but there were a lot of problems and errors … ‘/‘Quiz feature in [software name] does not work completely.’ |

Teaching and learning activities are organized in regular fashion, same as in f2f settings (e,f). Replicating regular teaching, without adaptations (f) Use different digital software (known or new), experiencing difficulties and not initiating changes (g) |

We observe statements of teachers who appear to almost resist the inevitable changes required for actually teaching online, refusing to consider the potential for teaching of online formats (Statements a, b). In statement (c), a clear blame-the-students posture is identifiable, functioning as self-justification for a situation where pedagogical attempts seem futile. Statement (d) indicates lack of teacher's involvement with online communication, which was left to the students. This is not only indicative of not engaging with activities typical to online teaching (i.e., communicating) but also of the teacher's averseness to adapt to a new, challenging situation. Statements (e) and (f) illustrate teaching online being enacted ‘as usual’, without changing and adjustments, replicating practice of f2f teaching in an online setting. Finally, statement (g) indicates teachers suggesting use of digital technologies (known or new), experiencing difficulties and not initiating changes. In terms of manifestations of agency, such statements match an iterational, non-transformative type of agency, where activity takes place but replicates existing practice; which in some cases may function well, while in times of crisis appears unsuitable. These postures can be interpreted as negative, but could also be viewed as static, or avoidant – teachers replicate what they know and usually do. Such a ‘replication’ conduct may be caused by lack of awareness of value of online teaching, insecurity about digital competence, or desire to deliver a perfect teaching experience but not being able to, and therefore not engaging in change. This type of conduct matches roughly Profile 1 in the LPA analysis, where level of activity is low in terms of engaging with new forms of teaching, technology and support seeking; constraints seem to be noted but not managed actively. Agency manifestations in this case are characterized by teachers recognizing the need for change, but enacting only familiar teaching, and thus displaying presumably mostly occlusive agency, as contingency and constrain prevail easily over intention to change or adapt their teaching.

5.3.2. Practical-evaluative and potentially transformative agency manifestations

While some teachers have approached the transition to emergency online learning by replicating regular teaching, others engaged the transition more thoughtfully. Excerpt 2 (Table 5 ) displays statements of teachers who report having tried out and evaluated different possibilities, with variable outcomes. Statement (a-c) illustrate teachers’ critical conclusions after having tested out new methods and having designed online teaching in emergency mode. While critical, the statements indicate that the teachers engaged in activities, but found the experience to be not necessarily positive for student learning or their themselves. Some of the experiences are nevertheless positive (Statement c); but conclude with identifying problems. This indicates that teachers may conceive of online teaching as a problem, generated by time pressure and other factors, despite the possibly useful experiences and knowledge accumulated. Statements (d-e) illustrate agentic manifestations characterized by trying out alternative methods for interaction online, work and communication, encountering problems, but also exploring/enabling solutions. This has a certain and latent transformative value, as there is a clear pro-active positioning and action, through which constraints are being addressed. These practical try-outs and evaluations may have positive or negative outcomes (failure or successes in changing teaching), but the experiences and ideas collected through these attempts are valuable and provide basis for subsequent decisions and actions for change.

In relation to the identified LPA profiles, this type of conduct may be associated with Profile 2, which indicates engagement with transitioning to online teaching. Teachers pursue online activities, by trying out methods and software, but are not decisive (or not indicating so) in how accumulated knowledge and experiences are to be used to further transform teaching practice or to manage constraints. This type of conduct matches a practical-evaluative type of agency, which has transformative potential. Yet, in the way teachers report it, this potential has been acknowledged but it is unclear whether it will/would be used to further change their practice once the emergency online teaching is concluded. In either category, teachers’ statements are not necessarily oriented towards suggesting ways out of this situation, or solutions, which may have added a more transformative value to conduct. Also this expression of agency can be qualified as occlusive, as teachers strive to find solutions in heavily constrained conditions.

5.3.3. Projective, transformative agency manifestations

The final set of thematic statements (Table 6 ) illustrate teachers’ experienced use of various software and methods (or combinations thereof), ways of productively using prior knowledge, new understanding of technologies and use of online teaching; and the way they viewed these efforts as challenging, but rewarding and transformative of future practice. Statements (a-c) are indicative of adaptive and transformative use of both teaching methods and software (e.g., Teams, Zoom, Canvas). The teachers adapted, in a simple but efficient way, the new methods for teaching to the contingency of the situation. They indicate that, after trying out and tweaking features, they have arrived at changed teaching setups that not only were productive in this emergency context, but proved to have potential for future teaching (a-b). These are indicative of explicit commitments to enhancing online learning, by employing methods, tools and experiences in concrete teaching situations.

Statements (d-f) are testimonies of expansive use of knowledge of (other forms of) online teaching such as MOOCs, accumulated through prior teaching engagements (d); pro-active support seeking, by searching and use of internet resources (e); and targeted participation in instructional events (conferences, webinars) that helped gain knowledge of digital technologies for online teaching. Teachers share the positive experience of being able to use knowledge developed over time and finding resources beyond the regular institutional arenas. These statements are also indicative of the teachers’ adaptive practice and of crossing boundaries of their regular practice for finding resources for teaching and own learning. Awareness of the value of pedagogical-digital competence is an important feature of this advanced agency expression. Finally, statements (g-h) illustrate positive postures of teachers who displayed transformative conduct, engaged pro-actively and experienced the positive outcomes of such conduct. Such postures are typical for teachers who are not only able to transform their own practice but also enable transformations for others.

The double orientation, towards ensuring good teaching by overcoming various constraints and capitalizing creatively on resources and towards identifying future is indicative of transformative agency. In relation to the LPA profiles, this type of conduct can be associated with Profile 3, wherein teachers reported fewer experienced challenges with online teaching. This can be also interpreted through the positive postures, as these teachers approached the constraints and contingencies with optimism and engaged in finding various solutions; which in turn, were rewarding for their practice. Such expansive conduct has empowering potential, and expresses a projective orientation, as practices and experiences, tools and situations are seen as valuable for future teaching. While constrains have been acknowledged, the type of agency expressed resembles the ostensible variant, with teachers pursuing new and challenging situations to create opportunities, instead of allowing them to limit their agency.

6. Discussion

This study aimed to contribute a better understanding of teachers' responses and agency in a digital, emergency teaching context. It did so by, first, empirically examining academic teachers' COVID-19-related online emergency teaching. The following research question guided the examination: 1) How can we categorize teachers' responses in the context of the transition to emergency online education? In addition, the study aimed at exploring and revisiting established notions of agency, habitually applied to teaching context, and re-elaborating a framework of agency in times of crisis. Research questions were: 2) What forms of agency were manifested in teachers’ responses in this transition? and 3) How can teacher agency be understood and (re)conceptualized in crisis contexts? The empirical exploration and conceptual work were aided by an operationalization based on established, theory-driven notion of agency (Emirbayer & Mische, 1998) and an applied notion of transformative agency (Haapasaari et al., 2016). The study has adopted an explorative approach and methods, including an abductive analytical approach and a conceptual elaboration, due to both the circumstances in which it was conducted and the emergent nature of the phenomenon examined. In the following, we discuss the findings and elaborate on the revisited framework for agency in times of crisis that emerged from this investigation.

6.1. Teachers’ conduct in online emergency teaching

In order to understand and categorize teachers' conduct in relation to the crisis situation, we first examined teachers’ responses to the need to transition from regular teaching to emergency online teaching. We operationalized conduct through the way teachers reported on use of new online teaching methods, digital resources (software) and seek support for their online teaching efforts, and on managing constraints encountered in transitioning to online emergency teaching. The findings show an array of rather diverse conduct.

The findings show rather limited variation in the number and types of online teaching methods teachers used. Overall, teachers reported that they lacked pedagogical knowledge and time, and needed to seek out forms of support beyond the regular support provided by their institution. These were identified as reasons for challenges or lack of success in online teaching, combined with pandemic-related challenges, such as the home situation. In parallel, the analyses attempting to identify and qualify agency manifestation have focused on the way teachers engaged these particular challenges. The degree of use of new online teaching methods is conceivably less important than the types of methods employed (Giovannella & Passarelli, 2020; Nambiar, 2020). The findings show that the majority of teachers switched to online teaching and used new forms of (online) teaching, however, many made the ‘safe’ choice, or perhaps, the choice for convenience by using lectures, often pre-recorded. Interactional forms of teaching and more advanced, flipped-classroom approaches seem to be less often used methods – at least in the first month of pandemic teaching. In relation to methods used, a challenge that stood out was the time to convert/redesign regular teaching into online teaching. This challenge is explained by the nature of the situation, as the switch to online settings needed to be done on a short notice (Dolonen et al., 2020; Watermeyer et al., 2020). At the same time, it may also be indicative of an unclear, possibly not always defined, both individual and institutional understanding of learning design and conditions important for generating online learning environments that meet the needs of the students; and of how these could be enacted by mobilizing existing digital infrastructure, competence and distributed online resources (King & Boyatt, 2014; Looi et al., 2019).

Academic teachers have proven to be creative in finding inspiration in various sources when designing their teaching, and indicate relying much upon their own resources, either found online or relational (colleagues, networks), often outside of their institutions’ boundaries. Perhaps surprisingly, while pedagogical expertise within their own institutions was also sought after and institutional resources were accessed in some cases, findings seem to indicate that this was not the main source of support, as also found by Hjelsvold et al. (2020). This situation may be indicative of teachers either not being aware of the existing institutional resources and support structures, or of these resources not addressing the very specific needs in this particular context (Allen, 2016; Luckin, 2018).

The findings prompt reflection on the challenges experienced by teachers in seeking digital support to enact online learning, and the way they engaged the digital challenge. The quality of the enactment of these teaching activities varied, as expected, due to various challenges. The private lockdown situation (of both academics and students) was expected to create difficulties in the current circumstances. The technical challenges and lack of experience with (new) software, as well as the need for support in managing these proficiently are clearly connected to aspects of digital infrastructure and services (cf. King & Boyatt, 2014), and to academics’ digital competence, as pointed out especially by Ilomäki and colleagues (2016) and Gudmundsdottir and Hatlevik (2018).

Teachers' responses to the need to transition to online teaching was categorized under three profiles: those who actively use new methods and software thoughtfully and managed constraints, and indicated sustainable changes to their way of teaching (profile 3); those who engaged moderately in making changes, experienced challenges and were less optimistic about their efforts (profile 2); and those who reported various constraints, that hindered teaching practices and successful delivery of teaching (profile 1). While rather generic, these three profiles are triggering the question about what kind of digital competence(s) is necessary in such online emergency context. Teachers frequently reported not being acquainted with the digital technologies, lack of competence and insecurity about technology used in pedagogical settings as main constraints. This is in line with Ilomäki and colleagues’ (2016) stance that digital competence can remain underdeveloped, as technology evolves rapidly and teachers may not be able to keep the pace, or underestimate the value of such competence in comparison to other competences. The way teachers include, or involve, digital technology in their teaching solutions on a regular basis – which may not be the customary way, can foster or limit the development of digital competence (Aagaard & Lund, 2020; Gudmundsdottir & Hatlevik, 2018). The majority of the teachers in our studies have indicated intention to realize online teaching, but the most explicit hindrance reported was digital competence and the way technologies could be accessed and embedded in the teaching of the subject on-the-fly. This increases the likelihood that, under the constraints of a crisis, access and use of digital infrastructure and resources will not become the main focus, as teacher must place their attention on the pedagogical design and delivery of good teaching. In order for subject-matter and profession-related digital competence (Gudmundsdottir & Hatlevik, 2018) to be developed and sustained, general digital competence and digital infrastructure and support needs to be in place. Such digital competence and infrastructure, thus, needs to be developed and consolidated over time and, preferably, connected to disciplinary contexts (cf. Pettersson, 2018), in order to be activated efficiently when the situation requires. This study underscores also a possibly trivial but essential detail, namely, that digital competence needs to be developed and maintained also beyond the (teaching) professional boundaries.

6.2. Agency revisited – a framework of teachers’ agency in times of crisis

In this study, we proposed a framework of agency that builds on a relational perspective on activity (Damsa & Jornet, 2017; Edwards, 2005; Stetsenko, 2016), which views the elements of the (teaching) environment - the teacher, resources, tools, institutions, infrastructure, communities - in a dynamic relationship. This framework enabled us to explain and illustrate how online teaching is realized as function of a combination, instead of singular traits, actions or external influences. In our framework, such constitutive factors are professional stance and digital competence, personal posture, teachers’ assumed responsibility, and the way opportunities and constraints converge to create the emergency teaching situation. The framework also illustrates the transformation potential of such a crisis situation, which triggers the emergence of new practices, even in a highly constrained context (Luckin, 2018).

From a relational perspective, agency appears as a multidimensional and composite construct, which holds both notions of individual conduct, but is intertwined with characteristics of the context. In accounting for the contextual factors, we create space for a more situated interpretation of teachers' agency, which is, in itself, never fully free of constraints or supportive structures. In our framework, we operationalized activities and constraints, examined them empirically, and interpreted them both in an inductive and deductive fashion, in order to understand whether and how teachers' conduct can be qualified in terms of types of agentic manifestations. The theory-driven initial framework, based on dimensions and features inspired by Emirbayer and Mische’s (1998) and Haapasaari and colleagues' (2016) work assisted interpretations of teachers' (self-reported) conduct with regard to their transformative nature.