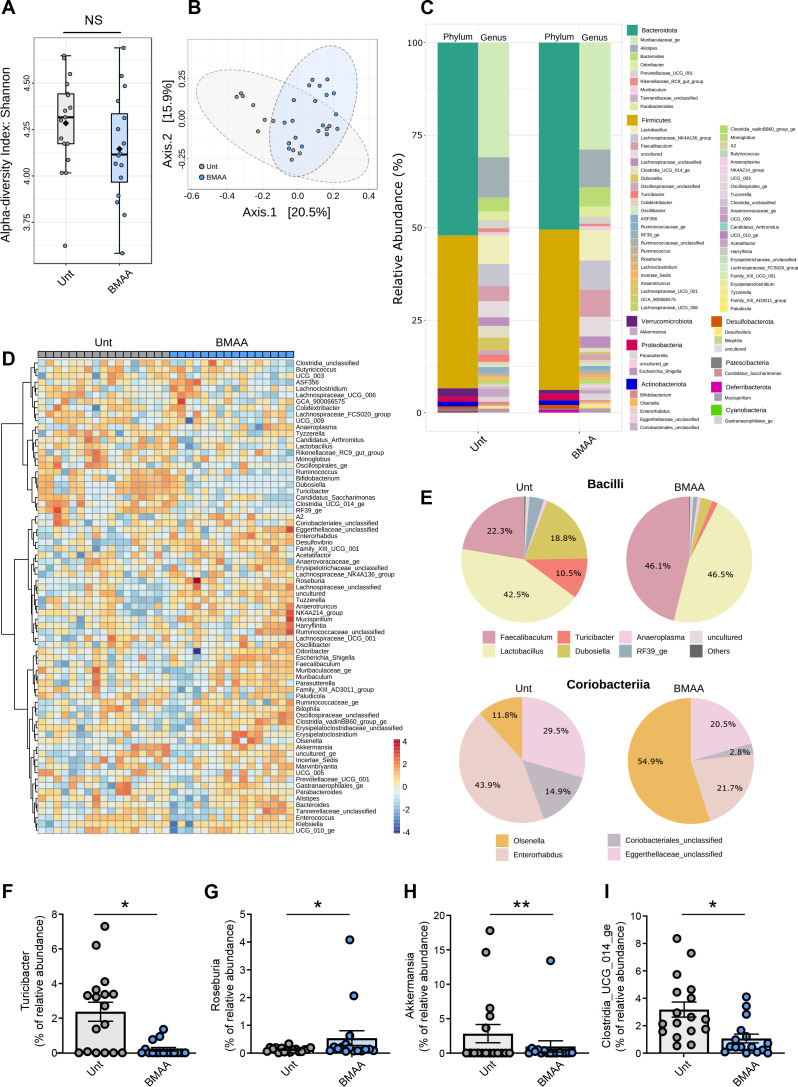

Figure 2.

Microbiome diversity in the stools of β-N-methylamino-L-alanine (BMAA)-treated mice. (A) Alpha diversity measured using the Shannon index at operational taxonomic unit (OTU) level derived from 16S rDNA sequences obtained from faecal samples from untreated (Unt) or BMAA-treated mice (n values for Unt=17 and BMAA=16, Unt versus BMAA, Mann-Whitney test, p=0.136). (B) Beta diversity evaluated by principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) based on Bray-Curtis index of OTUs derived from 16S rDNA sequencing of faecal samples from Unt or BMAA-treated mice (n values for Unt=16 and BMAA=16; PERMANOVA: r2=0.108, ***p<0.001; PERMDISP: F=2.378, p=0.134). (C) Taxonomic diversity of faecal microbiota from Unt or BMAA-treated mice at the phylum and genus levels. (D) Heatmap of relative abundances of the genera detected in the faeces from Unt or BMAA-treated mice using Pearson’s correlation coefficient as a distance metric, with clustering based on Ward’s algorithm. (E) Pie-charts showing the proportional taxonomic composition at the genus level of faecal microbiota samples from Unt or BMAA-treated mice for two selected class level taxa affected by BMAA treatment, Bacilli and Coriobacteria. (F–I) Differential abundance of selected genera in faecal samples from Unt or BMAA-treated mice (n values for Unt=17 and BMAA=16, Unt vs BMAA, DESeq2 statistical analysis). (F) Turicibacter (*padj=0.0169). (G) Roseburia (*padj=0.0242). (H) Akkermansia (**padj=0.0078). (I) Clostridia_UCG_014_ge (*padj=0.0190).