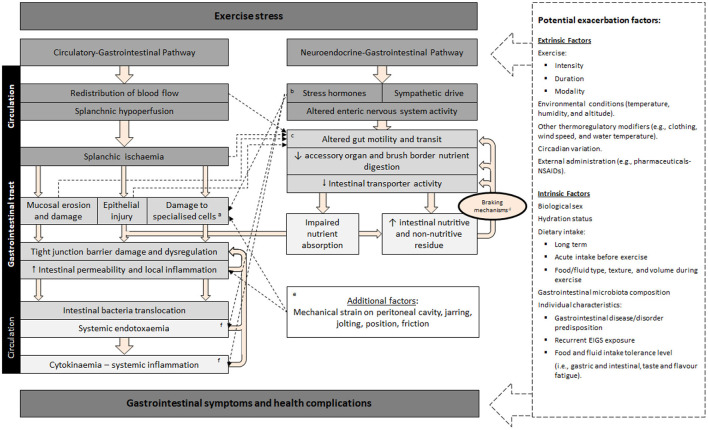

Figure 1.

Schematic description of exercise-induced gastrointestinal syndrome (EIGS): Physiological changes in circulatory and neuroendocrine pathways at the onset of exercise resulting in perturbed gastrointestinal integrity and function, which may lead to gastrointestinal symptoms, with performance and clinical implications (2, 3). aSpecialized antimicrobial protein-secreting (i.e., Paneth cells) and mucus-producing (goblet cells) cells, aid in preventing intestinal-originating pathogenic microorganisms entering systemic circulation. bSplanchnic hypoperfusion and subsequent intestinal ischemia and injury (including mucosal erosion) results from stress induced direct (e.g., enteric nervous system, and/or enteroendocrine cell) or indirect (e.g., braking mechanisms) alterations to gastrointestinal motility. cIncrease in neuroendocrine activation and suppressed submucosal and myenteric plexus result in epithelial cell loss and subsequent perturbed tight junctions (4, 5). dGastrointestinal brake mechanisms: Nutritive and non-nutritive residue along the small intestine, and inclusive of terminal ileum, results in neural and enteroendocrine negative feedback to gastric activity (6–10). eAggressive acute or low grade, prolonged mechanical strain, is proposed to contribute toward disturbances to epithelial integrity (i.e., epithelial cell injury and tight-junction dysregulation) and subsequent “knock-on” effects for gastrointestinal functional responses (11). fBacteria and bacterial endotoxin microorganism molecular patterns (MAMPs), and stress induced danger associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), are proposed to contribute toward the magnitude of systemic immune responses (e.g., systemic inflammatory profile) (12). Adapted from Costa et al. (2), with permission.