Abstract

Background

Exposure to nanoparticles became inevitable in our daily life due to their huge industrial uses. Copper oxide nanoparticles (CuONPs) are one of the most frequently utilized metal nanoparticles in numerous applications. Crocin (CRO) is a major active constituent in saffron having anti-inflammatory and antioxidant potentials.

Objectives

We designed this study to explore the probable defensive role of CRO against CuONPs-induced rat hepatic damage.

Materials and methods

Therefore, 24 adult rats were randomly distributed into 4 equal groups as negative control, CRO, CuONPs, and co-treated CuONPs with CRO groups. All treatments were administered for 14 days. The hepatotoxic effect of CuONPs was evaluated by estimation of hepatic alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase enzymes, hepatic oxidative malondialdehyde and antioxidant glutathione reduced, serum levels of inflammatory biomarkers (tumor necrosis factor-alpha, interleukin-1-beta, and nuclear factor kappa B), and expression of the apoptotic BAX in hepatic tissues; in addition, histopathological examination of the hepatic tissues was conducted.

Results

We found that concurrent CRO supplement to CuONPs-treated rats significantly averted functional and structural rat hepatic damage as documented by decreased hepatic enzymes activities, restored hepatic oxidant/antioxidant balance, decreased serum levels of inflammatory biomarkers, reversed BAX-mediated apoptotic cell death in hepatic tissues along with repair of CuONPs-induced massive hepatic structural and ultrastructural alterations.

Conclusions

It is concluded that combined CRO supplement to CuONPs-treated rats improved hepatic function and structure by, at least in part, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antiapoptotic mechanisms.

Keywords: Apoptosis, Copper oxide nanoparticles, Crocin, Hepatic injury, Hepatotoxicity

Introduction

Exposure to nanoparticles became inevitable in our daily life due to their huge industrial uses. Metal nanoparticles are of great significance in both development and research purposes. However, their uses have possible risks related to their short- and long-term toxicity to both humans and the environment.1–4 Copper (Cu) is an essential trace element in the human body. It acts as a key contributor to many physiological and metabolic pathways. However, excess copper is toxic and can result in hepatic damage as well as other organ damage.5 Copper oxide nanoparticles (CuONPs) are one of the most frequently utilized metal nanoparticles in numerous applications such as biomedicine, engineering, and technology fields. CuONPs can be used as industrial catalysts, gas sensors, electronic materials, magnet rotatable devices, and environmental remediation. They have excellent flexible properties by virtue of their large surface area to volume ratio and nanosize.6–8 Respiratory and dermal routes are the main portals of exposure to CuONPs in humans.8 Inhalation is the most significant route of environmental and occupational copper dust exposure owing to their nanosize and their ability to penetrate the pulmonary alveoli.9,10 Since CuONPs are commonly used in various applications in the medical field, reduced skin integrity or dermal dysfunction may increase dermal absorption of CuONPs-containing medical products when topically applied.11,12 Previous toxicological studies concerned with CuONPs attributed their toxic effects to oxidant injury, DNA damage, arrested organisms’ growth, and cellular death.13–15

The dried stigmas of Crocus sativus L. flowers are handled to produce saffron, the popular spice and food additive.16 Saffron is commonly used as herbal medicine as it is enriched in pharmacologically active compounds with a strong antioxidant action.17 Crocin (CRO) is a major active constituent in saffron having anti-inflammatory and antioxidant potential.18 Moreover, CRO exhibits other pharmacological effects such as analgesic, antiarthritic, and anticarcinogenic effects as well as reported favorable neuropsychiatric actions (antianxiety, antidepressant, antiepileptic, and memory-learning enhancing effects).19–23 However, the hepatoprotective effect of CRO has not been extensively studied. Consequently, this study was designed to explore the probable defensive role of CRO against CuONPs-induced rat hepatic damage through the assessment of hepatic enzyme activities, hepatic oxidant–antioxidant biomarkers, serum indicators of inflammation, and the apoptotic BAX expression in hepatic tissues, along with the histopathological examination of hepatic tissues.

Materials and methods

Chemicals

CuONPs (particle size is less than 50 nm and Product Number 5448680) and CRO (CAS number 17304) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, United States.

Characterization of CuONPs

Characterization of CuONPs was performed by the transmission electron microscope (TEM). At a concentration of 1 mg/mL, the dry powder of CuONPs was suspended in deionized water and then sonicated for 15 min at room temperature. The homogenate of CuONPs was placed on a carbon-coated copper grid, and then dried by air to be examined by TEM. TEM measurements were performed at an accelerating voltage of 80 kV (Model JEM-1400, JEOL Ltd, Tokyo, Japan). This characterization was performed in the Electron Microscopy Unit, Faculty of Agriculture Research Park (FARP), Cairo University, Cairo, Egypt.

Animals

The study included 24 adult male Wistar rats aged 4 to 6 weeks and weighing 200 to 250 g. Rats were supplied from the Zagazig Scientific and Medical Research Center (ZSMR) and maintained at the Breeding Animal House of Faculty of Medicine, Zagazig University, Zagazig, Egypt.

Ethics

All rats received humane care complied with the Animal Care Guidelines of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the Research Ethics Committee of Zagazig University approved the design of the study (Approval number: ZU-IACUC/3/F/95/2021). Rats were kept for 2 weeks to accommodate laboratory conditions. The rats were kept under optimal environmental conditions (temperature, 23 ± 2 °C, 12 h light/dark cycles and humidity 60 ± 5%, free access to food and tap water all time). The standard diet was supplied by El-Nasr Pharmaceutical Company. It was comprised of 72.2% carbohydrates, 3.4% fats, 19.8% proteins, 3.6% cellulose, 0.5% vitamins and minerals, and 0.5% salts.

Grouping of animals

Rats were randomly distributed into 4 groups (6 rats/group):

Group I (negative control): Received saline (0.5 mL).

Group II (CRO): supplemented with CRO in a dose of 30 mg kg−1 body weight, once daily for consecutive 14 days. CRO was dissolved in 0.5 mL normal saline (a concentration of 6 gm/100 mL normal saline).

Group III (CuONPs): treated with CuONPs in a dose of 100 mg kg−1 body weight, once daily for consecutive 14 days. CuONPs powder was dissolved in 0.5 mL normal saline (a concentration of 20 gm/100 mL normal saline) and was subjected to ultrasonic vibration for 15 min.

Group IV (CRO + CuONPs): supplemented with CRO in the same manner as in group II, after an hour, rats were treated with CuONPs as in group III.

All treatments were given through intraperitoneal injection (ip). The CuONPs dose was selected according to previous studies by Doudi and Setorki24 and Abdelazeim et al.25 At this dose, CuONPs-induced liver toxicity and hepatic histopathological alterations following 14 days. While the CRO dose was selected according to a previous study by Omidkhoda et al.18 At this dose, CRO protected against hepatic injury in aged rats.

Sample collection and preparation

Twenty-four hours after the last dose, rats were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal (ip) injection of pentobarbital (60 mg kg−1) before the collection of blood samples.26 Blood was collected from the retro-orbital plexus in plain tubes for the assessment of hepatic enzyme activities and levels of inflammatory biomarkers in serum. Serum was obtained by centrifugation of blood samples at 3000 rpm for 15 min at room temperature (stored at −20 °C). Then animals were euthanized by cervical dislocation and hepatic tissue specimens were excised immediately for assessment of hepatic oxidant–antioxidant status and histological examination.

Biochemical analysis

Hepatic enzymes assessment

The serum activity for liver enzymes [alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST)] was assessed according to Reitman and Frankel.27

Hepatic oxidative malondialdehyde (MDA) and antioxidant glutathione reduced (GSH) assessment

Both hepatic MDA and GSH levels were colorimetrically assayed according to Ohkawa et al.28 and Beutler et al.,29 respectively, using the commercially available assay kits (Biodiagnostic Company, Dokki, Giza, Egypt).

Serum levels of inflammatory biomarkers [tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-1-beta (IL-β), and nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB)] estimation

Serum levels of TNF-α, IL-β, and NF-κB were estimated by the commercial ELISA kits (RayBiotech, United States and CUSABIO) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Histological examination

Hepatic specimens were fixed in formal saline for 12 h to prepare paraffin blocks. Five-micrometer hepatic sections were prepared and stained by hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining.30 BAX immunohistochemical staining was performed using serial sections of paraffin blocks with a thickness of 4 μm. Then those blocks were placed in 10 mM citrate buffer (pH 6.0) and heated in a water bath at 98 °C for 30 min. Then hepatic sections were cooled at room temperature for 20 min, followed by washing under running tap water. Then sections were treated with 3% hydrogen peroxide in methanol for 15 min to block endogenous peroxidase activity.31 For TEM, according to Woods and Striling,32 hepatic specimens were immediately fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde in cacodylate buffer at pH 7.4 for 24 h at 4 °C. Then the specimens were washed with the buffer, post-fixed in 1% osmium tetroxide in distilled water for 2 h at 4 °C. Specimens were dehydrated with ascending grades of ethanol and then put in propylene oxide to prepare Epon-Araldite resin blocks. Ultrathin sections (70–90 nm) were obtained, stained by uranyl acetate and lead citrate. Stained grids were examined by a JEOL electron microscope 2100 at the Faculty of Agriculture, El-Mansoura University, El-Mansoura, Egypt.

Histomorphometry assessment

Optical density for BAX immunoexpression was quantified using the ImageJ analyzer computer system (Wayne Rasband, NIH, Bethesda, Maryland, United States).

Statistical analysis

Quantitative variables were displayed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). The normality of the quantitative variables was checked by Shapiro–Wilk test, while the equality of variance was checked by Bartlett’s test. The one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) or Welch’s ANOVA test was applied according to equality of variance to discover statistical differences among groups. Post hoc tests (Tukey’s test if equal variances are assumed or Dunnett’s T3 test if equal variances are not assumed) were performed for multiple comparisons between groups. The threshold of significance is P < 0.05. All statistical comparisons were two-tailed. All statistical analyses were estimated by Graphpad Prism, Version 8.0 Software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, United States).

Results

Characterization of CuONPs

TEM examination revealed that CuONPs were relatively spherical (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Transmission electron microscopy image of CuONPs. (TEM × 200000).

Death rates

No deaths were recorded in any study groups during the period of the experiment.

CRO supplement decreased the elevated liver enzymes induced by CuONPs in rats

CuONPs-intoxicated rats displayed statistically significantly higher ALT and AST enzyme activities compared with other study groups (P < 0.05). Simultaneous CRO supplementation to CuONPs-intoxicated rats for 14 days caused a significant decline in ALT and AST enzyme activities compared with CuONPs-treated rats (P = 0.008 and P < 0.001, respectively) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Effects of CRO on hepatic enzymes and hepatic biomarkers of oxidative stress, and serum levels of inflammatory biomarkers in CuONPs-induced hepatic injury in rats.

| Parameter | Groups | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative control | CRO | CuONPs | CRO + CuONPs | |

| ALT (IU/L) | 24 ± 2.8a | 21.8 ± 1.9a | 132.2 ± 17.2b | 46.3 ± 2.2c |

| AST (IU/L) | 39.5 ± 1.9a | 34.3 ± 4.4a | 172.7 ± 18.6b | 123.2 ± 3.8c |

| MDA (nmoL/g tissue) | 4.7 ± 0.8a | 4.6 ± 0.4a | 9.2 ± 0.6b | 5.9 ± 1c |

| GSH (mg/g tissue) | 24.1 ± 2.8a | 22.9 ± 2.3a | 17.2 ± 1.1b | 32.4 ± 1.7c |

| TNF-α (pg/mL) | 4 ± 0.4a | 3.7 ± 0.3a | 6.8 ± 1.1b | 4.2 ± 0.5a |

| IL-1β (pg/mL) | 426.5 ± 28.3a | 422.8 ± 34.3a | 834 ± 26.3b | 472.9 ± 98a |

| NF-κB (ng/mL) | 1.8 ± 0.5a | 1.7 ± 0.2a | 4.9 ± 0.7b | 2 ± 0.4a |

All values are displayed as mean ± SD, n = 6. Means in a row without a common superscript letter significantly differ (P < 0.05) by the one-way ANOVA test followed by post hoc Tukey’s multiple comparisons test or Welch’s one-way ANOVA test followed by post hoc Dunnett’s T3 multiple comparisons test according to the equality of variances. Abbreviations: CRO, Crocin; CuONPs, Copper oxide nanoparticles; ALT, Alanine aminotransferase; AST, Alanine aminotransferase; MDA, Malondialdehyde; GSH, glutathione reduced; TNF‑α, Tumor necrosis factor‑alpha; IL-1β, Interleukin‑1-beta; NF-κB, Nuclear factor kappa B.

CRO supplement displayed anti-inflammatory potential against CuOPNs exposure

CuONPs treatment caused inflammatory reactions proved by the significant increase in serum levels of inflammatory mediators (TNF-α, IL-β, and NF-κB) compared with other groups of the study (P < 0.05), while CRO supplement significantly decreased serum levels of inflammatory mediators (TNF-α, IL-β, and NF-κB) compared with CuONPs (P = 0.005, P < 0.001, and P < 0.001, respectively) (Table 1).

CRO supplement showed hepatic antioxidant potential against CuONPs-exposed rats

Administration of CuONPs for 14 days in rats significantly elevated hepatic MDA levels but significantly declined hepatic GSH levels compared with other study groups (P < 0.05). Co-treatment with CRO for 14 days caused a significant decline in hepatic MDA accompanied by a significant elevation in hepatic GSH levels compared with CuONPs-intoxicated rats (P < 0.001, each) (Table 1).

CRO supplementation alleviated hepatic histological derangements evoked by CuONPs administration in rats

Examination of H&E stained sections from the control group (Fig. 2a) and CRO-supplemented rats (Fig. 2c) was similar and revealed the normal hepatic histoarchitecture where the hepatocytes were arranged in cords radiating from the central hepatic vein and separated from each other by normal blood sinusoids. Normal portal areas at the corners of the hepatic lobules contained branches from the hepatic artery, portal vein, and bile duct were also shown in the hepatic sections of the control group (Fig. 2b) and CRO-supplemented rats (Fig. 2d). However, hepatic sections of the CuoNPs-treated group showed marked distortions of hepatic architecture with dilated and congested central veins along with congested and dilated hepatic sinusoids. Hydropic degeneration of hepatocytes and cellular infiltration could be seen. Ballooning of hepatocytes containing pale stained cytoplasm with few granules and darkly stained nuclei was visible. The portal triad displayed a dilated congested portal vein and thickening of its wall with a marked cellular infiltration. Also, cystic dilatation and proliferation of the bile duct were noted (Fig. (3a–c)). Hepatic sections of the CRO + CuONPs group revealed apparent improvement in the hepatic architecture compared with the CuONPs group. Most of the hepatocytes had vesicular nuclei and acidophilic cytoplasms. Apart from dilated central veins, congested dilated sinusoids, bile duct proliferation, and cellular infiltration, other histological changes appeared normal. Binucleated hepatocytes were also seen (Fig. (3d,e)).

Fig. 2.

Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained liver sections of the negative control and CRO groups. (H&E × 400). The negative control group: Fig. (2a,b) and the CRO group: Fig. (2c,d) showing cords of hepatocytes radiating from the central vein (CV) separated by blood sinusoids (S). Hepatocytes have round vesicular nuclei (H) and some are binucleated (curved arrow). Portal vein (PV) and bile duct (Bd) are observed.

Fig. 3.

Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained liver sections of CuONPs and CRO + CuONPs groups. (H&E × 400). The CuONPs group: Fig. (3a–c) showing enlarged hepatocytes containing pale stained cytoplasm with cytoplasmic vacuolation and darkly stained nuclei (arrowhead), the central vein is dilated and congested (CV). Also, the blood sinusoids are dilated and congested (S). The disturbed architecture of hepatocytes with cytoplasmic vacuolation is noticed (zigzag arrow). Portal area showing enlarged dilated portal vein with a thickened wall (PV), thick-walled bile duct (Bd) with duct proliferation. Leucocytic cellular infiltrations (double arrows) around the thickened bile duct are noticed. The CRO + CuONPs group: Fig. (3d,e) showing variable degrees of hepatic architecture improvement in comparison with that of the CuONPs group. Less dilated central vein (CV), dilated congested blood sinusoid (S), and some binucleated cells (curved arrow) are noticed. The portal triad: portal vein (PV), hepatic artery (HA) and proliferated bile duct (Bd) are observed. Still, some leucocytic cellular infiltrations (arrow) are noticed.

CRO supplementation reversed CuONPs-induced apoptotic cell death in rats’ hepatic tissues

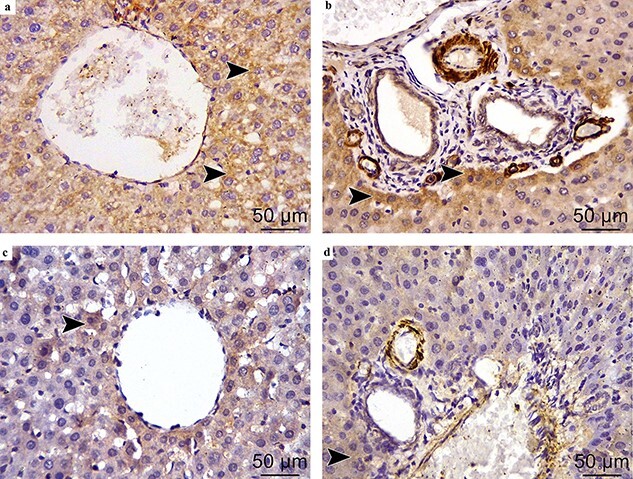

Immunohistochemically stained sections with anti-BAX antibodies from the control group (Fig. (4a,b)) and CRO-supplemented rats (Fig. (4c,d)) showing negative immune reactions for BAX inside the cytoplasm of the hepatocytes. While strong positive reaction for BAX is found in the CuONPs-treated rats (Fig. (5a,b)). The reaction intensity is apparently weakened in the CRO + CuONPs group (Fig. (5c,d)). Histomorphometry analysis of hepatic tissues shows that the mean optical density of hepatic BAX expression is significantly higher in the CuONPs group than in other study groups (P < 0.05), whereas the mean optical density of hepatic BAX expression is significantly lower after adding CRO to CuONPs-treated rats (0.21 ± 0.05 vs 0.035 ± 0.05, P = 0.005) (Fig. 6).

Fig. 4.

BAX-stained liver sections of the negative control and CRO groups. (BAX immunohistochemical staining × 400). The negative control group: Fig. (4a,b) and the CRO group: Fig. (4c,d) showing negative immune reactions for the cytoplasmic apoptotic BAX proteins.

Fig. 5.

BAX-stained liver sections of the CuONPs and CRO + CuONPs groups. (BAX immunohistochemical staining × 400). The CuONPs group: Fig. (5a,b) showing strong immune reaction in the cytoplasm of immunopositive hepatocytes (arrowhead).

The CRO + CuONPs group: Fig. (5c,d) showing weak immune reaction in the cytoplasm of immunopositive hepatocytes (arrowhead).

Fig. 6.

Effect of CRO on the optical density of BAX expression in hepatic tissues in CuONPs-induced hepatic injury in rats. Bars not sharing the common superscript letters differed significantly at P < 0.05 by Welch’s one-way ANOVA test followed by post hoc Dunnett’s T3 multiple comparisons test.

CRO supplementation repaired hepatic ultrastructural lesions induced by CuONPs administration in rats

By TEM, the hepatic tissue did not show relevant alterations among rats in the control group (Fig. (7a,b)) and CRO-supplemented rats (Fig. 7c) and it was comparable with the well-recognized normal ultrastructural pattern of the liver. The hepatocyte had a euchromatic spherical nucleus, granular cytoplasm, and normal organelles, for example, the rough endoplasmic reticulum (rER), which was visible as regular parallel linked tubules surrounding the nucleus. Normal rounded and elongated mitochondria were also visible. Kupffer cell appeared protruded into the sinusoidal lumen with a small euochromatic nucleus as well as its cytoplasm contained mitochondria, vacuoles, and rER. In the CuONPs group, the TEM examination displayed relevant ultrastructural changes. The hepatocytes had shrunken and heterochromatic nuclei with irregular nuclear membrane. The cytoplasm was densely packed with vacuoles and electron-dense lysosomes were found in the cytoplasm. Moreover, large membranous endosomes probably filled with CuONPs, irregular rER along with mitochondria with disrupted cristae, and few organelles were seen. Cell boundaries were ill-defined. Some hepatocytes appeared with electron-lucent cytoplasm. Few organelles and lysosomes were also visible inside the hepatocyte cytoplasm. Irregular short microvilli toward the blood sinusoids were noticed. Swollen Kupffer cells with multiple vacuoles in their cytoplasm were also detectable (Fig. (7d–f)). Adding CRO to CuONPs treatment diminished the remarkable ultrastructural lesions induced by CuONPs. Some hepatocytes retained their normal structure; euchromatic rounded nucleus, normal rounded elongated mitochondria, and regular parallel rER were seen. Less vacuolated cytoplasm was noticed compared with the CuONPs group. Kupffer cell displayed its normal structure. Few mitochondria were swollen and lysosomes were visible (Fig. 7g).

Fig. 7.

Transmission electron micrographs (TEM) of liver sections of all studied groups. The negative control group: Fig. 7a showing normal hepatocytes (H) with a euchromatic nucleus (N) with a well-developed nuclear membrane (arrowhead). The cytoplasm contains normal rounded and elongated mitochondria (M), regular rough endoplasmic reticulum (rER). Blood sinusoid (S) and normal Kupffer cells (K) with a normal nucleus (nu) and rounded elongated mitochondria (m) are observed. (TEM × 1200). Figure 7b showing hepatocyte with an euchromatic nucleus (N), cytoplasm contains normal rounded and elongated mitochondria (M), regular rough endoplasmic reticulum (rER). Short microvilli (thin arrow) projecting into the bile canaliculi (*) and sealed by tight junctions (thick arrow) at both sides are observed. (TEM × 2000). The CRO group: Fig. 7c showing normal hepatocytes with a euchromatic nucleus (N) with a well-developed nuclear membrane (arrowhead). The cytoplasm contains normal rounded and elongated mitochondria (M), regular rough endoplasmic reticulum (rER). (TEM × 1500). The CuONPs group: Fig. 7d showing a heterochromatic shrunken nucleus (N) with a prominent nucleolus (n) and electron lucent cytoplasm (C). Cytoplasmic vacuoles (V) and electron-lucent lipid vacuoles (double arrows), destructed mitochondria (M) and endosomes (curved arrow) are seen. (TEM × 1500). Figure 7e showing a heterochromatic nucleus (N) and irregular outlines (arrowhead), lysosomes (L), endosomes (curved arrow), destructed mitochondria (M), and irregular rough endoplasmic reticulum (rER). Hepatocytes enclosed bile canaliculi (*) with split microvilli sealed by tight junctions (thick arrow) at both sides. (TEM × 1500). Figure 7f showing Kupffer cell (K) with ovoid indented nucleus (N), destructed mitochondria (m), irregular rough endoplasmic reticulum (rER), electron-dense lysosomes (L), cytoplasmic vacuoles (V), and large membranous endosomes (curved arrow). Also, hepatocytes (H) and blood sinusoids (S) are observed. (TEM × 1500). The CRO + CuONPs group: Fig. 7g showing hepatocytes (H) with a euchromatic nucleus (N) and prominent nucleolus (n). Normal elongated mitochondria (M) and regular rough endoplasmic reticulum (rER). Blood sinusoids (S) and Kupffer cell (K) with indented nucleus (nu) are seen. Kupffer cells with vacuolated cytoplasm (V), lysosomes (L), and mitochondria (m) are also observed (TEM × 1000).

Discussion

CRO has aplenty of therapeutic effects in various disease conditions, e.g. neuropsychiatric disorders, musculoskeletal disorders, cardiovascular diseases, cancers, diabetes, etc.33 The promising neuropsychiatric actions of CRO have been verified in numerous human and experimental studies,20,34–40 however, a limited number of studies have been focused on the hepatoprotective effects of CRO, in particular, in a rat model of CuONPs-induced hepatic injury. Moreover, our study, for the first time, addressed the defensive role of CRO against CuONPs-induced hepatic injury through suppression of TNF-α, IL-β, and NF-κB along with downregulation of the apoptotic BAX in hepatic tissues.

The findings of the current study demonstrated the prophylactic role of CRO against CuONPs-induced liver injury in rats. The liver is the major target organ for nanomaterials-induced toxicity.3 Moreover, copper metabolism is mediated fundamentally by the liver. Earlier in vivo and in vitro studies established the hepatotoxic effects of CuONPs.41–43

In this study, the hepatotoxic effect of CuONPs was reflected by the significant elevation in hepatic enzyme activities, imbalanced hepatic oxidant/antioxidant status, increased hepatic inflammatory responses, in addition to extensive structural and ultrastructural hepatic aberrations along with intensified expression of apoptotic BAX in the hepatic tissues.

In support, a study by Abdelazeim et al.25 reported that a daily oral administration of CuONPs in a dose of 100 mg/Kg for 2 weeks to rats resulted in elevated hepatic enzyme activities, distorted hepatic oxidant-antioxidant balance, and increased levels of hepatic inflammatory indicators. Other studies related the extent and degree of hepatic injury to the activity of hepatic enzymes, exactly, ALT. Both ALT and AST are cytoplasmic enzymes and are directly released into the circulation in response to hepatic cellular damage.44,45

The imbalance between oxidants and antioxidants represents a fundamental basis of a multitude of hepatic diseases. Liver proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids are the most affected cellular structures secondary to oxidative stress injury.46 We found that CuONPs remarkably increased the hepatic content of MDA, a biomarker of lipid peroxidation, but decreased the antioxidant GSH. In agreement, the results of Anreddy’s study47 demonstrated the dose-dependent changes in antioxidant enzyme activities and molecules [catalase and superoxide dismutase activities, and GSH] caused by CuONPs. The author referred to the oxidative stress injury as a pertinent mechanism underlying the CuONPs-evoked hepatotoxicity.

Liver injury in response to any injurious agent resulted in activation of Kupffer cells, the resident macrophage population in the hepatic tissue, macrophage, and other immune cells invasion with subsequent initiation of hepatic inflammation.48 Accordingly, our results indicated the ability of CuONPs to trigger hepatic inflammatory reactions at biochemical and histological levels.

Bcl-2 family proteins are primary players in the control of cellular apoptosis/a programmed cell death. Some members of the Bcl-2 family, such as BAX, can trigger apoptosis and hinder cell survival.49 Exposure to CuONPs for 14 days in experimental rats showed overexpression of apoptotic BAX immunostaining in hepatic tissues. In corroboration, a study by Hassanen et al.50 ascertained the apoptotic potential of CuONPs as documented by overexpression of caspase-3 and upregulation of BAX gene as well as downregulation of the anti-apoptotic Bcl2 gene in both hepatic and renal tissues.

Prior studies confirmed the efficacy of CRO against various animal models of xenobiotic and non-xenobiotic induced liver injury such as acrylamide, carbon tetrachloride, ischemic/reperfusion injury, methotrexate, mycotoxin, and traumatic hemorrhagic shock.51–54 The joint mechanisms underpinning CRO benefits in these models are attributed mainly to anti-inflammatory, antioxidative, and antiapoptotic activities.

Excessive levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) can trigger inflammatory cellular pathways with the resultant release of numerous inflammatory biomarkers. Hence, oxidant injury and inflammation collaborate to cause cellular necrosis and apoptotic cell death. In addition, mitochondrial dysfunction, caspase activation, and Bcl-2 family proteins contribute to ROS-mediated apoptosis.55 In corroboration, we found that CuOPNs increased serum levels of the inflammatory biomarkers, increased oxidative MDA, decreased antioxidant GSH, along with hepatic infiltration of inflammatory cells and overexpression of the apoptotic BAX within the hepatic tissues.

ROS are incriminated in the activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) with the subsequent stimulation of transcription factors as the NF-κB that controls the expression of several proinflammatory biomarkers.56

The NF-κB is involved in a wide range of pathological and physiological conditions such as immune regulation, cell death, cell survival, and inflammatory response. The activation of the NF-κB signaling pathway leads to the synthesis and secretion of proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-1β. In this sense, CRO improved hepatic damage induced by CuOPNs, at least in part, through the suppression of the inflammatory signaling pathways involving NF-κB and cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-1β.57,58

Biochemical findings were confirmed by the histopathological and electron microscopy examination. CuONPs augmented the release of hepatic aminotransferases, induced oxidative stress, and triggered inflammatory reactions followed by striking hepatic histological and ultrastructural degenerative changes in rats, e.g. blood vessel congestion and dilation, hepatocytes ballooning, and inflammatory cellular infiltration. In addition, CRO attenuated hepatic histopathological aberrations induced by CuONPs.

In this work, CuONPs-evoked hepatic structural alterations in terms of central vein congestion, inflammatory cell infiltrations, and distribution of blood sinusoids could be correlated to the oxidant damage of lipids and proteins.59 Similarly, Abdelazeim et al.25 reported the injurious effects of CuONPs on hepatic tissues such as congestion of the central vein, focal hepatic necrosis, inflammatory infiltrates, and fibrosis in the portal triad. In corroboration, a study by Attia et al.60 displayed the ability of ethanolic saffron extract (60 mg kg−1) to reverse ultrastructural abnormalities in the hepatic tissues of mice treated with either 100 or 250 mg kg−1 for 30 days. Hassanen et al.50 attributed the ballooning of the hepatocytes and vacuolar degeneration to nanoparticles bioaccumulation and disturbed minerals homeostasis within the hepatic tissues.

In addition, the mitochondrial injury was an evident hepatic ultrastructural finding in rats exposed to CuONPs in our study. Liver mitochondria are the primary site for ROS generation. Moreover, ROS can disrupt mitochondrial function by alteration of the membrane permeability with subsequent cellular damage and metabolic disturbances.61,62

The histopathological results accorded with those of biochemical findings, thus confirming the hepatoprotective potential of CRO against CuONPs-induced hepatic damage.

Conclusions

CuONPs evoked liver injury in rats as demonstrated by the marked increase in the hepatic enzymes’ activities, disturbed hepatic oxidant/antioxidant balance, upregulated serum levels of inflammatory biomarkers as well as the extensive hepatic structural and ultrastructural deteriorations, and overexpression of the apoptotic BAX. Moreover, our study, for the first time, conferred the prophylactic role of CRO against CuONPs-induced hepatic injury in a rat model through suppression of TNF-α, IL-β, and NF-κB along with downregulation of the apoptotic BAX in hepatic tissues. Concurrent CRO administration to CuONPs-treated rats enhanced the hepatic function and structure by, at least in part, its antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antiapoptotic potentials. These findings underline the master role of dietary natural molecules and offer a novel strategy to cope with CuONPs-induced hepatotoxicity.

Authors’ contributions

D.M.Y and E.R.A. designed the experiment. O.E.N. performed data analysis and wrote the original draft. All authors contributed to drafting, and revising the article, approved the final version, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the study.

Funding

None.

Conflict of interest statement

There are no conflicts of interest to declare.

Contributor Information

Doaa Mohammed Yousef, Department of Anatomy and Embryology, Faculty of Medicine, Zagazig University, Zagazig 44519, Egypt.

Heba Ahmed Hassan, Department of Clinical Pharmacology, Faculty of Medicine, Zagazig University, Zagazig 44519, Egypt.

Ola Elsayed Nafea, Department of Forensic Medicine and Clinical Toxicology, Faculty of Medicine, Zagazig University, Zagazig 44519, Egypt; Department of Clinical Pharmacy, College of Pharmacy, Taif University, P.O. Box 11099, Taif 21944, Saudi Arabia.

Eman Ramadan Abd El Fattah, Department of Anatomy and Embryology, Faculty of Medicine, Zagazig University, Zagazig 44519, Egypt.

References

- 1. El-wafaey DI, Nafea OE, Faruk EM. Naringenin alleviates hepatic injury in zinc oxide nanoparticles exposed rats: impact on oxido-inflammatory stress and apoptotic cell death. Toxicol Mech Methods. 2021:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Egbuna C, Parmar VK, Jeevanandam J, Ezzat SM, Patrick-Iwuanyanwu KC, Adetunji CO, Khan J, Onyeike EN, Uche CZ, Akram M, et al. Toxicity of nanoparticles in biomedical application: Nanotoxicology. J Toxicol. 2021:2021:1–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sun T, Kang Y, Liu J, Zhang Y, Ou L, Liu X, Lai R, Shao L. Nanomaterials and hepatic disease: toxicokinetics, disease types, intrinsic mechanisms, liver susceptibility, and influencing factors. J Nanobiotechnology. 2021:19(1):108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. García-Torra V, Cano A, Espina M, Ettcheto M, Camins A, Barroso E, Vazquez-Carrera M, García ML, Sánchez-López E, Souto EB. State of the art on toxicological mechanisms of metal and metal oxide nanoparticles and strategies to reduce toxicological risks. Toxics. 2021:9(8):195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gaetke LM, Chow-Johnson HS, Chow CK. Copper: toxicological relevance and mechanisms. Arch Toxicol. 2014:88(11):1929–1938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Khan I, Saeed K, Khan I. Nanoparticles: properties, applications and toxicities. Arab J Chem. 2019:12(7):908–931. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Naz S, Gul A, Zia M. Toxicity of copper oxide nanoparticles: a review study. IET Nanobiotechnol. 2020:14(1):1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Assadian E, Zarei MH, Gilani AG, Farshin M, Degampanah H, Pourahmad J. Toxicity of copper oxide (CuO) nanoparticles on human blood lymphocytes. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2018:184(2):350–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Valavanidis A, Vlachogianni T, Fiotakis K, Loridas S, Perdicaris S. Potential toxicity and safety evaluation of nanomaterials for the respiratory system and lung cancer. Lung Cancer Targets Ther. 2013:4:71–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Skoczyńska A, Gruszczyński L, Wojakowska A, Ścieszka M, Turczyn B, Schmidt E. Association between the type of workplace and lung function in copper miners. Biomed Res Int. 2016:2016:1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cohen D, Soroka Y, Maor Z, Oron M, Portugal-Cohen M, Brégégère FM, Berhanu D, Valsami-Jones E, Hai N, Milner Y. Evaluation of topically applied copper(II) oxide nanoparticle cytotoxicity in human skin organ culture. Toxicol in Vitro. 2013:27(1):292–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zanoni I, Crosera M, Ortelli S, Blosi M, Adami G, Larese Filon F, Costa AL. CuO nanoparticle penetration through intact and damaged human skin. New J Chem. 2019:43(43):17033–17039. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Midander K, Cronholm P, Karlsson HL, Elihn K, Möller L, Leygraf C, Wallinder IO. Surface characteristics, copper release, and toxicity of nano- and micrometer-sized copper and copper(II) oxide particles: a cross-disciplinary study. Small. 2009:5(3):389–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Baek YW, An YJ. Microbial toxicity of metal oxide nanoparticles (CuO, NiO, ZnO, and Sb2O3) to Escherichia coli, Bacillus subtilis, and Streptococcus aureus. Sci Total Environ. 2011:409(8):1603–1608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Karlsson HL, Cronholm P, Gustafsson J, Möller L. Copper oxide nanoparticles are highly toxic: a comparison between metal oxide nanoparticles and carbon nanotubes. Chem Res Toxicol. 2008:21(9):1726–1732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Moratalla-López B. Lorenzo, Salinas and Alonso. Bioactivity and bioavailability of the major metabolites of Crocus sativus L. flower. Molecules. 2019:24(15):2827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Su X, Yuan C, Wang L, Chen R, Li X, Zhang Y, Liu C, Liu X, Liang W, Xing Y. The beneficial effects of saffron extract on potential oxidative stress in cardiovascular diseases. Oxidative Med Cell Longev. 2021:2021:1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Omidkhoda SF, Mehri S, Heidari S, Hosseinzadeh H. Protective effects of crocin against hepatic damages in D-galactose agingmodel in rats. Iran J Pharm Res IJPR. 2020:19(3):440–450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Colapietro A, Mancini A, D’Alessandro AM, Festuccia C. Crocetin and crocin from saffron in cancer chemotherapy and chemoprevention. Anticancer. Agents. Med Chem. 2019:19(1):38–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zhang L, Previn R, Lu L, Liao R-F, Jin Y, Wang RK. Crocin, a natural product attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced anxiety and depressive-like behaviors through suppressing NF-kB and NLRP3 signaling pathway. Brain Res Bull. 2018:142:352–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Farkhondeh T, Samarghandian S, Shaterzadeh Yazdi H, Samini F. The protective effects of crocin in the management of neurodegenerative diseases: a review. Am J Neurodegener Dis. 2018:7(1):1–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ding Q, Zhong H, Qi Y, Cheng Y, Li W, Yan S, Wang X. Anti-arthritic effects of crocin in interleukin-1β-treated articular chondrocytes and cartilage in a rabbit osteoarthritic model. Inflamm Res. 2013:62(1):17–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Erfanparast A, Tamaddonfard E, Taati M, Dabbaghi M. Effects of crocin and safranal, saffron constituents, on the formalin-induced orofacial pain in rats. Avicenna J Phytomedicine. 2015:5:392–402. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Doudi M, Setorki M. Acute effect of nano-copper on liver tissue and function in rat. Nanomedicine J. 2014:1(5):331–338. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Abdelazeim SA, Shehata NI, Aly HF, Shams SGE. Amelioration of oxidative stress-mediated apoptosis in copper oxide nanoparticles-induced liver injury in rats by potent antioxidants. Sci Rep. 2020:10(1):1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Leal Filho MB, Morandin RC, Almeida AR, Cambiucci EC, Metze K, Borges G, Gontijo JAR. Hemodynamic parameters and neurogenic pulmonary edema following spinal cord injury: an experimental model. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2005:63(4):990–996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Reitman S, Frankel S. A colorimetric method for the determination of serum glutamic oxalacetic and glutamic pyruvic transaminases. Am J Clin Pathol. 1957:28(1):56–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Beutler E, Duron O, Kelly BM. Improved method for the determination of blood glutathione. J Lab Clin Med. 1963:61:882–888. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ohkawa H, Ohishi N, Yagi K. Assay for lipid peroxides in animal tissues by thiobarbituric acid reaction. Anal Biochem. 1979:95(2):351–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bancroft JD, Lyton C. In: Suvarna SK, Bancroft JD, Lyton C, editors. Theory and Practice of Histological Techniques. 8th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2019. pp. 126–138 [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sanderson T, Wild G, Cull AM, Marston J, Zardin G. Bancroft’s Theory and Practice of Histological Techniques. 8th ed. Phialdelphia: Elsevier; 2019. pp. 337–396 [Google Scholar]

- 32. Woods A, Stirling J. In: Suvarna SK, Bancroft JD, Lyton C, editors. Bancroft’s Theory and Practice of Histological Techniques. 8th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2019. pp. 434–475 [Google Scholar]

- 33. Song Y, Wang Y, Zheng Y, Liu T, Zhang C. Crocins: a comprehensive review of structural characteristics, pharmacokinetics and therapeutic effects. Fitoterapia. 2021:153:104969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kermanshahi S, Ghanavati G, Abbasi-Mesrabadi M, Gholami M, Ulloa L, Motaghinejad M, Safari S. Novel neuroprotective potential of crocin in neurodegenerative disorders: an illustrated mechanistic review. Neurochem Res. 2020:45(11):2573–2585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Musazadeh V, Zarezadeh M, Faghfouri AH, Keramati M, Ghoreishi Z, Farnam A. Saffron, as an adjunct therapy, contributes to relieve depression symptoms: An umbrella meta-analysis. Pharmacol Res. 2022:175:105963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ayati Z, Yang G, Ayati MH, Emami SA, Chang D. Saffron for mild cognitive impairment and dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised clinical trials. BMC Complement Med Ther. 2020:20(1):333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Dai L, Chen L, Wang W. Safety and Efficacy of Saffron (Crocus sativus L.) for treating mild to moderate depression. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2020:208(4):269–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Marx W, Lane M, Rocks T, Ruusunen A, Loughman A, Lopresti A, Marshall S, Berk M, Jacka F, Dean OM. Effect of saffron supplementation on symptoms of depression and anxiety: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr Rev. 2019:77(8):557–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Shafiee M, Arekhi S, Omranzadeh A, Sahebkar A. Saffron in the treatment of depression, anxiety and other mental disorders: Current evidence and potential mechanisms of action. J Affect Disord. 2018:227:330–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hausenblas HA, Heekin K, Mutchie HL, Anton S. A systematic review of randomized controlled trials examining the effectiveness of saffron (Crocus sativus L.) on psychological and behavioral outcomes. J Integr Med. 2015:13(4):231–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Liu H, Lai W, Liu X, Yang H, Fang Y, Tian L, Li K, Nie H, Zhang W, Shi Y, et al. Exposure to copper oxide nanoparticles triggers oxidative stress and endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-stress induced toxicology and apoptosis in male rat liver and BRL-3A cell. J Hazard Mater. 2021:401:123349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lee IC, Ko JW, Park SH, Shin NR, Shin IS, Moon C, Kim JH, Kim HC, Kim JC. Comparative toxicity and biodistribution assessments in rats following subchronic oral exposure to copper nanoparticles and microparticles. Part Fibre Toxicol. 2016:13(1):56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Chen Z, Meng H, Xing G, Chen C, Zhao Y, Jia G, Wang T, Yuan H, Ye C, Zhao F, et al. Acute toxicological effects of copper nanoparticles in vivo. Toxicol Lett. 2006:163(2):109–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lin S, Chung T, Lin C, Ueng T-H, Lin Y, Lin S, Wang L. Hepatoprotective Effects of Arctium Lappa on carbon tetrachloride- and acetaminophen-induced liver damage. Am J Chin Med. 2000:28(02):163–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Stockham SL, Scott MA. Fundamentals of Veterinary Clinical Pathology. 2nd ed. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010. pp. 675–706 [Google Scholar]

- 46. Cichoż-Lach H. Oxidative stress as a crucial factor in liver diseases. World J Gastroenterol. 2014:20(25):8082–8091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Anreddy RNR. Copper oxide nanoparticles induces oxidative stress and liver toxicity in rats following oral exposure. Toxicol Rep. 2018:5:903–904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Koyama Y, Brenner DA. Liver inflammation and fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 2017:127(1):55–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. D’Arcy MS. Cell death: a review of the major forms of apoptosis, necrosis and autophagy. Cell Biol Int. 2019:43(6):582–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hassanen EI, Tohamy A, Issa MY, Ibrahim MA, Farroh KY, Hassan AM. Pomegranate juice diminishes the mitochondria-dependent cell death and NF-kB signaling pathway induced by copper oxide nanoparticles on liver and kidneys of rats. Int J Nanomedicine. 2019:14:8905–8922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Boussabbeh M, Ben Salem I, Belguesmi F, Neffati F, Najjar MF, Abid-Essefi S, Bacha H. Crocin protects the liver and kidney from patulin-induced apoptosis in vivo. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2016:23(10):9799–9808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Akbari G, Mard SA, Dianat M. Effect of crocin on cardiac antioxidants, and hemodynamic parameters after injuries induced by hepatic ischemia-reperfusion in rats. Iran J Basic Med Sci. 2019:22(3):277–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Kalantar M, Kalantari H, Goudarzi M, Khorsandi L, Bakhit S, Kalantar H. Crocin ameliorates methotrexate-induced liver injury via inhibition of oxidative stress and inflammation in rats. Pharmacol Rep. 2019:71(4):746–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Liu Y, Yao C, Wang Y, Liu X, Xu S, Liang L. Protective Effect of crocin on liver function and survival in rats with traumatic hemorrhagic shock. J Surg Res. 2021:261:301–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Mahmoud AM, Wilkinson FL, Sandhu MA, Lightfoot AP. The interplay of oxidative stress and inflammation: mechanistic insights and therapeutic potential of antioxidants. Oxidative Med Cell Longev. 2021:2021:9851914. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Arab HH, Salama SA, Maghrabi IA. Camel milk ameliorates 5-fluorouracil-induced renal injury in rats: targeting MAPKs, NF-κB and PI3K/Akt/eNOS pathways. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2018:46(4):1628–1642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. George B, Suchithra TV, Bhatia N. Burn injury induces elevated inflammatory traffic: the role of NF-κB. Inflamm Res. 2021:70(1):51–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Da Silveira AR, Rosa ÉVF, Sari MHM, Sampaio TB, Dos Santos JT, Jardim NS, Müller SG, Oliveira MS, Nogueira CW, Furian AF. Therapeutic potential of beta-caryophyllene against aflatoxin B1-Induced liver toxicity: biochemical and molecular insights in rats. Chem Biol Interact. 2021:348:109635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Singh J, Phogat A, Prakash C, Chhikara SK, Singh S, Malik V, Kumar V. N-Acetylcysteine reverses monocrotophos exposure-induced hepatic oxidative damage via mitigating apoptosis,inflammation and structural changes in rats. Antioxidants. 2021:11(1):90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Attia AA, Ramdan HS, Al-Eisa RA, Adle Fadle BOA, El-Shenawy NS. Effect of saffron extract on the hepatotoxicity induced by copper nanoparticles in male mice. Molecules. 2021:26(10):3045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Zorov DB, Juhaszova M, Sollott SJ. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) and ROS-induced ROS release. Physiol Rev. 2014:94(3):909–950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Brookins Danz ED, Skramsted J, Henry N, Bennett JA, Keller RS. Resveratrol prevents doxorubicin cardiotoxicity through mitochondrial stabilization and the Sirt1 pathway. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009:46(12):1589–1597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]